The evolution of conspicuous facultative mimicry in octopuses: an ...

The evolution of conspicuous facultative mimicry in octopuses: an ...

The evolution of conspicuous facultative mimicry in octopuses: an ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

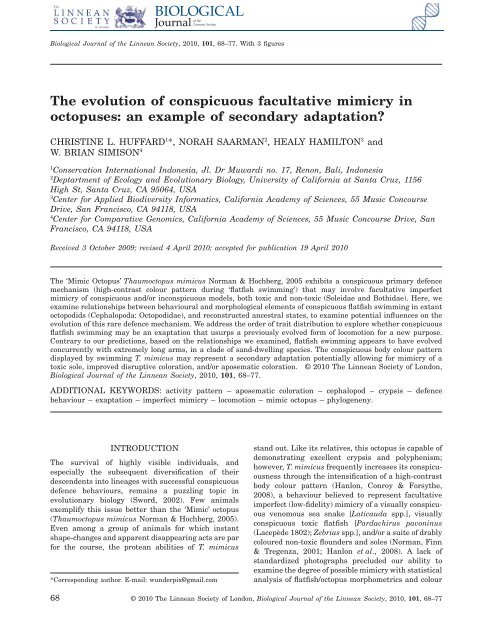

Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77. With 3 figures<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> <strong>facultative</strong> <strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>octopuses</strong>: <strong>an</strong> example <strong>of</strong> secondary adaptation?<br />

CHRISTINE L. HUFFARD 1 *, NORAH SAARMAN 2 , HEALY HAMILTON 3 <strong>an</strong>d<br />

W. BRIAN SIMISON 4<br />

1Conservation International Indonesia, Jl. Dr Muwardi no. 17, Renon, Bali, Indonesia<br />

2Deptartment <strong>of</strong> Ecology <strong>an</strong>d Evolutionary Biology, University <strong>of</strong> California at S<strong>an</strong>ta Cruz, 1156<br />

High St, S<strong>an</strong>ta Cruz, CA 95064, USA<br />

3Center for Applied Biodiversity Informatics, California Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences, 55 Music Concourse<br />

Drive, S<strong>an</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>cisco, CA 94118, USA<br />

4Center for Comparative Genomics, California Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, S<strong>an</strong><br />

Fr<strong>an</strong>cisco, CA 94118, USA<br />

Received 3 October 2009; revised 4 April 2010; accepted for publication 19 April 2010bij_1484<br />

68..77<br />

<strong>The</strong> ‘Mimic Octopus’ Thaumoctopus mimicus Norm<strong>an</strong> & Hochberg, 2005 exhibits a <strong>conspicuous</strong> primary defence<br />

mech<strong>an</strong>ism (high-contrast colour pattern dur<strong>in</strong>g ‘flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g’) that may <strong>in</strong>volve <strong>facultative</strong> imperfect<br />

<strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> <strong>an</strong>d/or <strong>in</strong><strong>conspicuous</strong> models, both toxic <strong>an</strong>d non-toxic (Soleidae <strong>an</strong>d Bothidae). Here, we<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>e relationships between behavioural <strong>an</strong>d morphological elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> ext<strong>an</strong>t<br />

octopodids (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae), <strong>an</strong>d reconstructed <strong>an</strong>cestral states, to exam<strong>in</strong>e potential <strong>in</strong>fluences on the<br />

<strong>evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> this rare defence mech<strong>an</strong>ism. We address the order <strong>of</strong> trait distribution to explore whether <strong>conspicuous</strong><br />

flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g may be <strong>an</strong> exaptation that usurps a previously evolved form <strong>of</strong> locomotion for a new purpose.<br />

Contrary to our predictions, based on the relationships we exam<strong>in</strong>ed, flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g appears to have evolved<br />

concurrently with extremely long arms, <strong>in</strong> a clade <strong>of</strong> s<strong>an</strong>d-dwell<strong>in</strong>g species. <strong>The</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> body colour pattern<br />

displayed by swimm<strong>in</strong>g T. mimicus may represent a secondary adaptation potentially allow<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>of</strong> a<br />

toxic sole, improved disruptive coloration, <strong>an</strong>d/or aposematic coloration. © 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London,<br />

Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77.<br />

ADDITIONAL KEYWORDS: activity pattern – aposematic coloration – cephalopod – crypsis – defence<br />

behaviour – exaptation – imperfect <strong>mimicry</strong> – locomotion – mimic octopus – phylogeneny.<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

<strong>The</strong> survival <strong>of</strong> highly visible <strong>in</strong>dividuals, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

especially the subsequent diversification <strong>of</strong> their<br />

descendents <strong>in</strong>to l<strong>in</strong>eages with successful <strong>conspicuous</strong><br />

defence behaviours, rema<strong>in</strong>s a puzzl<strong>in</strong>g topic <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>evolution</strong>ary biology (Sword, 2002). Few <strong>an</strong>imals<br />

exemplify this issue better th<strong>an</strong> the ‘Mimic’ octopus<br />

(Thaumoctopus mimicus Norm<strong>an</strong> & Hochberg, 2005).<br />

Even among a group <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong>imals for which <strong>in</strong>st<strong>an</strong>t<br />

shape-ch<strong>an</strong>ges <strong>an</strong>d apparent disappear<strong>in</strong>g acts are par<br />

for the course, the prote<strong>an</strong> abilities <strong>of</strong> T. mimicus<br />

*Correspond<strong>in</strong>g author. E-mail: wunderpix@gmail.com<br />

68<br />

st<strong>an</strong>d out. Like its relatives, this octopus is capable <strong>of</strong><br />

demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g excellent crypsis <strong>an</strong>d polyphenism;<br />

however, T. mimicus frequently <strong>in</strong>creases its <strong>conspicuous</strong>ness<br />

through the <strong>in</strong>tensification <strong>of</strong> a high-contrast<br />

body colour pattern (H<strong>an</strong>lon, Conroy & Forsythe,<br />

2008), a behaviour believed to represent <strong>facultative</strong><br />

imperfect (low-fidelity) <strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>of</strong> a visually <strong>conspicuous</strong><br />

venomous sea snake [Laticauda spp.], visually<br />

<strong>conspicuous</strong> toxic flatfish [Pardachirus pavon<strong>in</strong>us<br />

(Lacepède 1802); Zebrias spp.], <strong>an</strong>d/or a suite <strong>of</strong> drably<br />

coloured non-toxic flounders <strong>an</strong>d soles (Norm<strong>an</strong>, F<strong>in</strong>n<br />

& Tregenza, 2001; H<strong>an</strong>lon et al., 2008). A lack <strong>of</strong><br />

st<strong>an</strong>dardized photographs precluded our ability to<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>e the degree <strong>of</strong> possible <strong>mimicry</strong> with statistical<br />

<strong>an</strong>alysis <strong>of</strong> flatfish/octopus morphometrics <strong>an</strong>d colour<br />

© 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London, Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77

patterns. Although the toxicity <strong>of</strong> T. mimicus is<br />

unknown, it may be unpalatable (Norm<strong>an</strong> & Hochberg,<br />

2006), <strong>an</strong>d potentially displays honest warn<strong>in</strong>g coloration.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se behaviours are neurally controlled rather<br />

th<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>atomically fixed. Thaumoctopus mimicus c<strong>an</strong><br />

regulate <strong>conspicuous</strong>ness while imitat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>imals<br />

(mobile <strong>an</strong>d sessile) or <strong>in</strong><strong>an</strong>imate objects, <strong>an</strong>d frequently<br />

challenges the dist<strong>in</strong>ction between <strong>mimicry</strong><br />

<strong>an</strong>d crypsis (Endler, 1981; H<strong>an</strong>lon et al., 2008). By<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>conspicuous</strong>ness <strong>an</strong>d possibly <strong>mimicry</strong>,<br />

rather th<strong>an</strong> crypsis, <strong>in</strong>to its primary defence, the<br />

<strong>an</strong>cestors <strong>of</strong> these <strong>octopuses</strong> experienced a behavioural<br />

shift from a situation <strong>in</strong> which ‘the operator does not<br />

perceive the mimic <strong>an</strong>d therefore makes no decision’, to<br />

one based on the predator detect<strong>in</strong>g the mimic <strong>an</strong>d<br />

subsequently be<strong>in</strong>g deceived (Endler, 1981), or receiv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

honest warn<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

VISUAL DEFENCES IN CEPHALOPODS<br />

Crypsis <strong>an</strong>d polyphenism are the most common<br />

primary defences (behaviours that decrease the predator’s<br />

ch<strong>an</strong>ces <strong>of</strong> encounter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d detect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>imal<br />

as a prey item; Edmunds, 1974) <strong>in</strong> shallow-water<br />

octopodids (hereafter referred to as <strong>octopuses</strong>; H<strong>an</strong>lon<br />

& Messenger, 1996). Although <strong>octopuses</strong> are functionally<br />

colour-bl<strong>in</strong>d (Marshall & Messenger, 1996;<br />

Mäthger et al., 2006), m<strong>an</strong>y species have evolved<br />

through selective predation pressure the me<strong>an</strong>s to<br />

match their background shape, sk<strong>in</strong> pattern, texture,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d colour almost <strong>in</strong>st<strong>an</strong>tly (Packard, 1972). When<br />

motionless, some cephalopods c<strong>an</strong> atta<strong>in</strong> such excellent<br />

camouflage that public forums have <strong>in</strong>correctly<br />

questioned the authenticity <strong>of</strong> videotaped examples,<br />

such as one described recently by H<strong>an</strong>lon (2007;<br />

contested <strong>in</strong> http://www.metacafe.com/watch/1001148/<br />

amaz<strong>in</strong>g_camouflage/). In addition to crypsis achieved<br />

by the sk<strong>in</strong>, their flexible bodies also allow them a<br />

tremendous diversity <strong>of</strong> body postures (Huffard, 2006).<br />

By ch<strong>an</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g shape frequently (polyphenism) <strong>octopuses</strong><br />

may impair their predators’ formation <strong>an</strong>d use <strong>of</strong> a<br />

search image (H<strong>an</strong>lon, Forsythe & Joneschild, 1999).<br />

Crypsis is compromised each time <strong>an</strong> octopus<br />

moves to forage or escape predators (H<strong>an</strong>lon et al.,<br />

1999; Huffard, Boneka & Full, 2005; Huffard, 2006).<br />

Species that live on rocky reefs c<strong>an</strong> duck <strong>in</strong>to crevices<br />

<strong>an</strong>d camouflage themselves aga<strong>in</strong>st habitat irregularities<br />

when they traverse terra<strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong>d risk draw<strong>in</strong>g<br />

attention to themselves (H<strong>an</strong>lon, 2007). By contrast,<br />

<strong>octopuses</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> homogeneous low-relief habitats<br />

like s<strong>an</strong>d pla<strong>in</strong>s have few opportunities for concealment,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d are especially vulnerable to exposure while<br />

away from their dens. <strong>The</strong>se <strong>octopuses</strong> sometimes<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporate deceptive resembl<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>in</strong>to locomotion<br />

(pl<strong>an</strong>t matter, H<strong>an</strong>lon & Messenger, 1996; Huffard<br />

et al., 2005; flatfish, Hoover, 1998; H<strong>an</strong>lon et al., 2008;<br />

CONSPICUOUS FACULTATIVE MIMICRY IN OCTOPUSES 69<br />

H<strong>an</strong>lon, Watson & Barbosa, 2010), thereby sidestepp<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the need to hide per se. However, <strong>in</strong> most <strong>of</strong><br />

these examples <strong>octopuses</strong> still imitate other cryptic<br />

objects or <strong>an</strong>imals.<br />

Visually <strong>conspicuous</strong> primary defences appear to be<br />

rare <strong>in</strong> cephalopods. In all known cases they occur <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>octopuses</strong> that c<strong>an</strong> otherwise exhibit excellent camouflage.<br />

<strong>The</strong> t<strong>in</strong>y blue-r<strong>in</strong>ged <strong>octopuses</strong> (Hapalochlaena<br />

spp.) flash iridescent aposomatic body patterns to warn<br />

<strong>of</strong> a tetrodotox<strong>in</strong>-laced bite (H<strong>an</strong>lon & Messenger,<br />

1996); these r<strong>in</strong>gs c<strong>an</strong> also be visible when the <strong>an</strong>imal<br />

is rest<strong>in</strong>g. Examples <strong>of</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> <strong>mimicry</strong> consist <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>octopuses</strong> imitat<strong>in</strong>g visually obvious fish. <strong>The</strong> large<br />

Octopus cy<strong>an</strong>ea Gray, 1849 (French Polynesia) c<strong>an</strong><br />

resemble the shape <strong>an</strong>d body-colour pattern <strong>of</strong> a noncryptic<br />

parrotfish when swimm<strong>in</strong>g well above complex<br />

reef structures (H<strong>an</strong>lon et al., 1999). Octopus <strong>in</strong>sularis<br />

Leite, et al. 2008 has been reported to exhibit <strong>facultative</strong><br />

social <strong>mimicry</strong> by temporarily imitat<strong>in</strong>g the fish<br />

with which it happens to be associated at the time<br />

(Krajewski et al., 2009).<br />

Perhaps the most widely publicized though <strong>in</strong>sufficiently<br />

<strong>an</strong>alysed example <strong>of</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> defence<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>octopuses</strong> is <strong>conspicuous</strong> ‘flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g’ by<br />

T. mimicus, found on s<strong>an</strong>d pla<strong>in</strong>s throughout the<br />

Indo-West Pacific (Norm<strong>an</strong> et al., 2001). ‘Flatfish<br />

swimm<strong>in</strong>g’ comprises the follow<strong>in</strong>g behavioural<br />

elements: similar swimm<strong>in</strong>g durations <strong>an</strong>d speeds<br />

to that <strong>of</strong> flatfish, arms positioned to atta<strong>in</strong> flatfish<br />

shape, both eyes positioned prom<strong>in</strong>ently as flatfish<br />

eyes, <strong>an</strong>d undulat<strong>in</strong>g movements <strong>of</strong> arms dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

swimm<strong>in</strong>g that resemble f<strong>in</strong> movements <strong>of</strong> flatfish<br />

(H<strong>an</strong>lon et al., 2008). Thus far it has been reported for<br />

T. mimicus, Macrotritopus defilippi (Ver<strong>an</strong>y, 1851),<br />

‘White V’ octopus, <strong>an</strong>d the ‘Hawaii<strong>an</strong> Long-Armed<br />

S<strong>an</strong>d Octopus’ (Hoover, 1998; H<strong>an</strong>lon et al., 2008;<br />

H<strong>an</strong>lon et al., 2010). Unlike the latter three <strong>octopuses</strong>,<br />

which rema<strong>in</strong> camouflaged dur<strong>in</strong>g flatfish<br />

swimm<strong>in</strong>g, T. mimicus consistently <strong>in</strong>corporates<br />

<strong>conspicuous</strong>ness, with a high-contrast dark brown<br />

<strong>an</strong>d light cream body-colour pattern (H<strong>an</strong>lon et al.,<br />

2008). Whereas all <strong>of</strong> the <strong>octopuses</strong> mentioned here<br />

are capable <strong>of</strong> acute crypsis, at times T. mimicus<br />

utilizes a primary defence that makes no attempt at<br />

camouflage, <strong>an</strong>d may actually aim to draw attention.<br />

TOWARDS AN EVOLUTIONARY UNDERSTANDING OF A<br />

CONSPICUOUS PRIMARY DEFENCE IN T. MIMICUS<br />

Here we report patterns <strong>of</strong> behavioural trait distribution<br />

<strong>in</strong> ext<strong>an</strong>t <strong>octopuses</strong> <strong>an</strong>d reconstructed <strong>an</strong>cestral<br />

states to explore possible scenarios for the <strong>evolution</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> T. mimicus.<br />

Relationships among species, traits, <strong>an</strong>d their reconstructed<br />

<strong>an</strong>cestral states c<strong>an</strong> provide a highly<br />

<strong>in</strong>formative framework for underst<strong>an</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g ch<strong>an</strong>ges <strong>in</strong><br />

© 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London, Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77

70 C. L. HUFFARD ET AL.<br />

both behaviour <strong>an</strong>d morphology through time (W<strong>in</strong>terbottom<br />

& McLenn<strong>an</strong>, 1993). Central to this <strong>in</strong>vestigation<br />

is the well-documented fact that m<strong>an</strong>y behaviours,<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g visual defences <strong>an</strong>d their associated body<br />

colour patterns (e.g. Brodie III, 1989), are heritable<br />

traits. Support<strong>in</strong>g the idea that flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

<strong>in</strong>herited is the observation <strong>of</strong> this behaviour <strong>in</strong> a<br />

laboratory-reared octopus (the behaviourally, ecologically,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d morphological similar M. defilippi) that had<br />

never seen a flatfish (H<strong>an</strong>lon et al., 2010). Given the<br />

widespread use <strong>of</strong> flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> T. mimicus,<br />

‘White V’, M. defilippi, <strong>an</strong>d the Hawaii<strong>an</strong> Long-Armed<br />

S<strong>an</strong>d Octopus, <strong>an</strong>d its absence <strong>in</strong> other observed<br />

species that are also sympatric with flatfish, we<br />

assume that the ability to express this behaviour is a<br />

genetically determ<strong>in</strong>ed presence/absence trait. However,<br />

recent reports <strong>of</strong> possible social <strong>mimicry</strong> (Krajewski<br />

et al., 2009) <strong>an</strong>d conditional learn<strong>in</strong>g (Hvorecny<br />

et al., 2007) <strong>in</strong> <strong>octopuses</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t to the possibility that<br />

environmental cues <strong>an</strong>d learn<strong>in</strong>g may also <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

the expression <strong>of</strong> the traits exam<strong>in</strong>ed here.<br />

We address the order <strong>of</strong> trait distribution to explore<br />

whether <strong>conspicuous</strong> flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g may <strong>in</strong>corporate<br />

<strong>an</strong> exaptation that usurps a previously evolved<br />

form <strong>of</strong> locomotion for new purpose, as previously<br />

hypothesized (Huffard, 2006), or if it may be <strong>an</strong> adaptation.<br />

With adaptation, <strong>an</strong>atomical ch<strong>an</strong>ges <strong>an</strong>d<br />

correspond<strong>in</strong>g behavioural uses evolve at the same<br />

time (Blackburn, 2002). Exaptations, by contrast, are<br />

traits that ‘are fit for their current role ...but were<br />

not designed for it’ (Gould & Vrba, 1982), hav<strong>in</strong>g<br />

evolved orig<strong>in</strong>ally either as adaptations for other<br />

uses, or when <strong>in</strong>extricably l<strong>in</strong>ked to other selected<br />

traits (Andrews, G<strong>an</strong>gestad & Matthews, 2002). Once<br />

established, exaptations c<strong>an</strong> then be followed by secondary<br />

adaptations related to the new use (Gould &<br />

Vrba, 1982). Specifically, we consider the onsets <strong>of</strong>:<br />

(1) activity dur<strong>in</strong>g daylight hours (either diurnal or<br />

crepuscular); (2) the use <strong>of</strong> ‘dorsoventrally compressed’<br />

swimm<strong>in</strong>g (DVC; swimm<strong>in</strong>g with the head<br />

<strong>an</strong>d m<strong>an</strong>tle lowered <strong>an</strong>d the arms spread laterally;<br />

Fig. 1D; Video S1); (3) high-contrast dark-brown <strong>an</strong>d<br />

light/white body (HCDL) patterns <strong>in</strong> the deimatic<br />

(‘bluff’) display; (4) expression <strong>of</strong> flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g;<br />

<strong>an</strong>d (5) HCDL visible at rest, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g high-contrast<br />

arm b<strong>an</strong>ds. All <strong>of</strong> these traits are considered essential<br />

to the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g as a<br />

visual defence. <strong>The</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> very long arms (here<br />

considered to be 6.5 times the m<strong>an</strong>tle length) is<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ed as a potential morphological correlate to<br />

flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g because it may allow the better<br />

imitation <strong>of</strong> undulat<strong>in</strong>g flatfish f<strong>in</strong>s.<br />

Potential visibility to predators, whether via<br />

exposed habitat or daytime activity, c<strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence the<br />

<strong>evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> visual defences (Mart<strong>in</strong>s, Marquez &<br />

Sazima, 2008). We predict that diurnal activity was<br />

<strong>an</strong> <strong>evolution</strong>ary precursor to <strong>conspicuous</strong> flatfish<br />

swimm<strong>in</strong>g, enabl<strong>in</strong>g generations <strong>of</strong> visual predators<br />

to select aga<strong>in</strong>st poor mimics. <strong>The</strong> HCDL body patterns,<br />

<strong>in</strong> particular <strong>in</strong> the form <strong>of</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ct arm b<strong>an</strong>ds,<br />

impart <strong>conspicuous</strong>ness <strong>in</strong> this defence. In m<strong>an</strong>y<br />

octopus species the deimatic display dur<strong>in</strong>g secondary<br />

defence <strong>in</strong>volves high-contrast disruptive body patterns<br />

<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g light <strong>an</strong>d dark components (Fig. 1;<br />

Messenger, 2001). Thus HCDL is likely to have<br />

evolved early <strong>in</strong> this l<strong>in</strong>eage.<br />

Dorsoventrally compressed swimm<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>an</strong> essential<br />

aspect <strong>of</strong> flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g. In form, these two<br />

modes <strong>of</strong> locomotion are similar, but DVC does not<br />

necessarily <strong>in</strong>corporate the imitation <strong>of</strong> flatfish: the<br />

entire head <strong>an</strong>d m<strong>an</strong>tle may be raised rather th<strong>an</strong><br />

just the eyes, <strong>an</strong>d the arms need not undulate like<br />

flatfish f<strong>in</strong>s. For example, both Abdopus aculeatus<br />

(d’Orbigny, 1834) <strong>an</strong>d Wunderpus photogenicus Hochberg,<br />

Norm<strong>an</strong> & F<strong>in</strong>n, 2006 (Video S1) employ DVC,<br />

but not flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

<strong>The</strong> DVC mode <strong>of</strong> swimm<strong>in</strong>g may also be <strong>an</strong> efficient<br />

way for long-armed <strong>octopuses</strong> to swim. This<br />

streaml<strong>in</strong>ed mode <strong>of</strong> locomotion may <strong>in</strong>corporate lift,<br />

to <strong>in</strong>crease biomech<strong>an</strong>ic efficiency (Huffard, 2006) <strong>an</strong>d<br />

combat the known physiological <strong>in</strong>efficiencies <strong>of</strong> jetpropelled<br />

locomotion <strong>in</strong> <strong>octopuses</strong> (Wells et al., 1987;<br />

Wells, 1990). DVC may be particularly import<strong>an</strong>t to<br />

<strong>octopuses</strong> with high mass relative to their jetpropulsive<br />

abilities, such as very large <strong>octopuses</strong> or<br />

those with disproportionally long arms. Heavier <strong>octopuses</strong><br />

swim relatively slower (body lengths/time) th<strong>an</strong><br />

<strong>octopuses</strong> with less mass (as <strong>in</strong> A. aculeatus; Huffard,<br />

2006). All else be<strong>in</strong>g equal, arm mass would be higher<br />

<strong>in</strong> long-armed <strong>octopuses</strong> th<strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong> their shorter-armed<br />

relatives. Yet without a correspond<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong><br />

m<strong>an</strong>tle size <strong>an</strong>d volume, long-armed <strong>octopuses</strong> are<br />

likely to exhibit disproportionally weaker jetpropulsive<br />

abilities, <strong>an</strong>d may need to rely more on lift<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g swimm<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

MATERIAL AND METHODS<br />

To exam<strong>in</strong>e the relationships <strong>of</strong> shallow water <strong>octopuses</strong><br />

(Table S1) we estimated genealogical relationships<br />

among mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) l<strong>in</strong>eages<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g Bayesi<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d maximum-likelihood (ML)<br />

methods, as implemented <strong>in</strong> MrBayes MPI v3.1.2<br />

(Appendix S1; Huelsenbeck et al., 2001; Ronquist &<br />

Huelsenbeck, 2003; Altekar et al., 2004) <strong>an</strong>d PAUP*<br />

v4.0b10 (Sw<strong>of</strong>ford, 2002), respectively. <strong>The</strong> specific<br />

model chosen was the ‘best-fit model’ (SYM + I + G)<br />

selected by Akaike’s <strong>in</strong>formation criterion (AIC) <strong>in</strong><br />

MrModeltest 2.3 (Nyl<strong>an</strong>der, 2004). For the Bayesi<strong>an</strong><br />

<strong>an</strong>alyses, the alignment was partitioned <strong>in</strong>to four<br />

blocks: 16S <strong>an</strong>d the three codon positions for<br />

cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI). <strong>The</strong>se genes were<br />

© 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London, Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77

72 C. L. HUFFARD ET AL.<br />

chosen because they are well represented for octopodids<br />

<strong>in</strong> GenB<strong>an</strong>k, allow<strong>in</strong>g for a broad sampl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

taxa. MrModeltest was <strong>in</strong>dependently applied to each<br />

partition. Three different models were assigned to the<br />

four partitions (for 16S <strong>an</strong>d the first COI codon position<br />

we used nst = 6 rates = <strong>in</strong>vgamma GTR + G + I;<br />

for the third COI codon position we used nst = 6<br />

rates = gamma GTR + Gamma; <strong>an</strong>d for the second COI<br />

codon position we used HKY + I). <strong>The</strong> MrBayes <strong>an</strong>alysis<br />

(Appendix S2) r<strong>an</strong> for 50 000 000 generations, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

we sampled every 1000 trees. We determ<strong>in</strong>ed a burn-<strong>in</strong><br />

value by exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the sample parameter values<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g Tracer v1.4. <strong>The</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> parameter<br />

values reached stationarity by 12 500 trees. For ML<br />

<strong>an</strong>alyses, trees were rooted us<strong>in</strong>g the out-group species<br />

noted above. <strong>The</strong> specific model chosen was the best-fit<br />

model (SYM + I + G) selected by AIC <strong>in</strong> MrModeltest<br />

2.3: the concatenated COI <strong>an</strong>d 16S alignment length is<br />

1216 base pairs; tr<strong>an</strong>sition/tr<strong>an</strong>sversion ratio =<br />

2.9925; nucleotide frequencies, A = 0.2638, C = 0.2675,<br />

G = 0.2404, <strong>an</strong>d T = 0.2282; rates = gamma; shape<br />

parameter for a gamma distribution = 0.5625; <strong>an</strong>d<br />

P<strong>in</strong>var = 0.4712. ML <strong>an</strong>alyses were conducted us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the heuristic search mode with ‘as is’ addition <strong>an</strong>d TBR<br />

br<strong>an</strong>ch-swapp<strong>in</strong>g. ML Bootstrap <strong>an</strong>alyses (1000 replicates)<br />

used the same model <strong>an</strong>d search options as<br />

above. All <strong>an</strong>alyses were performed on <strong>an</strong> 88-core<br />

Apple Xserve Xeon cluster, us<strong>in</strong>g the iNquiry bio<strong>in</strong>formatics<br />

cluster tool (v2.0, build 755). Specimens were<br />

collected from localities throughout the tropical<br />

Pacific, <strong>an</strong>d we compared these taxa with exist<strong>in</strong>g<br />

samples deposited <strong>in</strong> GenB<strong>an</strong>k (Table S1). Out-groups<br />

were specimens <strong>of</strong> Vampyropteuthis <strong>an</strong>d Argonauta<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g the results <strong>of</strong> previous <strong>in</strong>vestigations <strong>in</strong>to<br />

cephalopod phylogeny (Carl<strong>in</strong>i, Young & Vecchione,<br />

2001; L<strong>in</strong>dgren, Giribet & Nishiguchi, 2004).<br />

To our knowledge, the result<strong>in</strong>g tree (Fig. 2)<br />

is currently the only reconstruction <strong>of</strong> Octopodid<br />

relationships that <strong>in</strong>cludes Thaumoctopus <strong>an</strong>d its relatives,<br />

onto which we could map behavioral characters.<br />

Onto this tree we mapped arm lengths <strong>an</strong>d behavioural<br />

traits based on published literature, the first<br />

author’s own experiences observ<strong>in</strong>g these <strong>an</strong>imals, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

unpublished data from cephalopod biologists (Fig. 3;<br />

Table S2). In the event <strong>of</strong> discrep<strong>an</strong>cies between our<br />

observations <strong>an</strong>d published accounts we followed our<br />

own observations, as these were typically made on the<br />

<strong>an</strong>imal that was the source <strong>of</strong> exam<strong>in</strong>ed DNA. Ancestral<br />

states were reconstructed follow<strong>in</strong>g unordered<br />

parsimony (Mesquite 2.5).<br />

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION<br />

PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS<br />

Thaumoctopus mimicus appears most closely related<br />

to the crepuscular W. photogenicus. <strong>The</strong>se two<br />

<strong>octopuses</strong> appear closely related to the ‘White V’<br />

octopus, which overlaps both species (at least<br />

partially) <strong>in</strong> geographic r<strong>an</strong>ge, habitat, <strong>an</strong>d activity<br />

patterns. <strong>The</strong> ecologically similar but geographically<br />

dist<strong>an</strong>t ‘Hawaii<strong>an</strong> Long-Armed S<strong>an</strong>d Octopus’ is also<br />

found <strong>in</strong> this clade. We recommend that these latter<br />

<strong>octopuses</strong> be placed <strong>in</strong> the genus Thaumoctopus (with<br />

the genus Wunderpus treated as a synonym) when<br />

described, because <strong>of</strong> nom<strong>in</strong>al seniority. Because the<br />

Thaumoctopus + Wunderpus clade does not reflect a<br />

unified taxonomic group<strong>in</strong>g, we refer to this as the<br />

‘Long-Armed S<strong>an</strong>d Octopus’ clade (LASO). Tissue for<br />

the behaviourally, ecologically, <strong>an</strong>d morphologically<br />

similar M. defilippi was not available. LASO appears<br />

sister to the highly cryptic <strong>an</strong>d primarily diurnal<br />

Abdopus clade, found <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tertidal <strong>an</strong>d subtidal reef<br />

flats throughout the tropical Pacific. <strong>The</strong> clade formed<br />

by LASO + Abdopus is sister to the O. cy<strong>an</strong>ea clade <strong>of</strong><br />

large but cryptic reef-dwell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>octopuses</strong>. Morphological,<br />

genetic, <strong>an</strong>d behavioural aff<strong>in</strong>ities among these<br />

<strong>octopuses</strong> have been noted previously (Norm<strong>an</strong> &<br />

F<strong>in</strong>n, 2001; Guzik, Norm<strong>an</strong> Mark & Crozier, 2005;<br />

Huffard, 2007). Octopus cy<strong>an</strong>ea Gray, 1849, described<br />

as one s<strong>in</strong>gle species from Australia, is commercially<br />

import<strong>an</strong>t throughout its r<strong>an</strong>ge (Norm<strong>an</strong>, 1992), <strong>an</strong>d<br />

represents at least three dist<strong>in</strong>ct populations (Hawaii,<br />

the L<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>an</strong>ds, <strong>an</strong>d Indonesia).<br />

PATTERNS OF TRAIT DISTRIBUTION<br />

Contrary to a previous prediction (Huffard, 2006),<br />

flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g by LASO does not appear to be <strong>an</strong><br />

exaptation. Rather, both DVC <strong>an</strong>d flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

may have evolved <strong>in</strong> conjunction with exceptionally<br />

long arms <strong>in</strong> their most recent common <strong>an</strong>cestor. In<br />

this case, it appears that correspond<strong>in</strong>g behavioural<br />

<strong>an</strong>d morphological traits emerge concurrently, follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong> ‘adaptation’ (Blackburn, 2002).<br />

This potential adaptation may have yielded selective<br />

adv<strong>an</strong>tages via possible flatfish <strong>mimicry</strong>, improved<br />

biomech<strong>an</strong>ic efficiency, or both. Because some gape<br />

predators <strong>of</strong> LASO may not be able to fit <strong>an</strong> adult<br />

flatfish <strong>in</strong>to their mouth quickly, flatfish <strong>mimicry</strong><br />

without imitation <strong>of</strong> a toxic model may still provide<br />

survival <strong>an</strong>d fitness adv<strong>an</strong>tages (Huffard, 2006).<br />

LASO + A. aculeatus species all have long arms <strong>an</strong>d<br />

exhibit DVC. This mode <strong>of</strong> locomotion may have<br />

evolved to combat the <strong>in</strong>efficiencies <strong>of</strong> forward (eyes or<br />

arms-first) swimm<strong>in</strong>g by <strong>octopuses</strong> with long arms.<br />

Octopus kaurna Str<strong>an</strong>ks, 1990 <strong>an</strong>d Callistoctopus<br />

ornatus (Gould, 1852) also have long arms, but unlike<br />

LASO + Abdopus species, their dorsal arms are disproportionally<br />

robust compared with their ventral<br />

arms. This morphology may impose unique locomotory<br />

constra<strong>in</strong>ts on forward swimm<strong>in</strong>g that may have<br />

precluded the <strong>evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> DVC.<br />

© 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London, Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77

0.1<br />

0.75<br />

0.98<br />

0.98<br />

0.92<br />

0.66<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> use <strong>of</strong> HCDL dur<strong>in</strong>g primary<br />

defence appears unique to T. mimicus <strong>an</strong>d<br />

W. photogenicus. <strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased expression <strong>of</strong> this<br />

body pattern may represent a secondary adaptation<br />

for possible <strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>conspicuous</strong> models, a form <strong>of</strong><br />

disruptive coloration, or possibly honest signall<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> unpalatability. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> HCDL <strong>in</strong> the deimatic<br />

display appears concurrently with diurnal activity<br />

<strong>in</strong> the most recent common <strong>an</strong>cestor <strong>of</strong> LASO +<br />

1.00<br />

0.90<br />

0.99<br />

0.65<br />

1.00<br />

0.72<br />

0.87<br />

1.00<br />

1.00<br />

1.00<br />

CONSPICUOUS FACULTATIVE MIMICRY IN OCTOPUSES 73<br />

0.81<br />

0.98<br />

0.92<br />

1.00<br />

1.00<br />

0.99<br />

1.00<br />

1.00<br />

1.00<br />

1.00<br />

0.92<br />

0.97<br />

0.99<br />

1.00<br />

0.84<br />

0.93<br />

0.76<br />

0.73<br />

1.00<br />

Vampyroteuthis <strong>in</strong>fernalis (GB)<br />

Bathypolypus arcticus (GB)<br />

Cistopus <strong>in</strong>dicus (Fish Market, Phuket, Thail<strong>an</strong>d)<br />

Octopus cy<strong>an</strong>ea (Maui, Hawaii)<br />

Octopus cy<strong>an</strong>ea (SE Sulawesi, Indonesia)<br />

Octopus cy<strong>an</strong>ea (Palmyra, L<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>an</strong>ds)<br />

Abdopus sp. 1 (Oahu, Hawaii)<br />

Abdopus acuelatus (SE Sulawesi, Indonesia)<br />

Abdopus "sp. Ward" (Guam, Micronesia)<br />

"Hawaii<strong>an</strong> Long Armed S<strong>an</strong>d" octopus (Oahu, Hawaii)<br />

"White V" octopus (N Sulawesi, Indonesia)<br />

Wunderpus photogenicus (N Sulawesi, Indonesia)<br />

Thaumoctopus mimicus (N Sulawesi, Indonesia)<br />

Octopus bocki (Moorea, Society Isl<strong>an</strong>ds)<br />

Octopus oliveri (Oahu, Hawaii)<br />

Octopus sp. 1 (Oahu, Hawaii)<br />

Octopus bimaculoides (California, USA)<br />

Octopus vulgaris (GB)<br />

Amphioctopus aeg<strong>in</strong>a (GB)<br />

Amphioctopus arenicola (Oahu, Hawaii)<br />

Amphioctopus marg<strong>in</strong>atus (N Sulawesi, Indonesia)<br />

Hapalochlaena lunulata (Pet trade, Cebu, Philipp<strong>in</strong>es)<br />

Hapalochlaena fasciata (New South Wales, Australia)<br />

Hapalochlaena maculosa (GB)<br />

Octopus cf. mercatoris (Pet trade, Florida, USA)<br />

Octopus kaurna (GB)<br />

Callistoctopus ornatus (Oahu, Hawaii)<br />

Callistoctopus cf. aspilosomatis (Palmyra, L<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>an</strong>ds)<br />

Callistoctopus luteus (Oahu, Hawaii)<br />

Argonauta argo (OG)<br />

Argonauta nodosa (OG)<br />

Japatella diaph<strong>an</strong>a (GB)<br />

Vitreledonella richardi (GB)<br />

Thaumeledone sp. (GB)<br />

Pareledone charcoti (GB)<br />

Gr<strong>an</strong>eledone <strong>an</strong>tarctica ( GB)<br />

Gr<strong>an</strong>eledone verrucosa (GB)<br />

Benthoctopus sp. (GB)<br />

Octopus californicus (GB)<br />

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationships (location given <strong>in</strong> parentheses). Numeric values represent Bayesi<strong>an</strong> posterior<br />

probabilities.<br />

Abdopus + O. cy<strong>an</strong>ea + Cistopus <strong>in</strong>dicus (d’Orbigny,<br />

1840), <strong>an</strong>d aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the most recent common <strong>an</strong>cestor<br />

<strong>of</strong> O. bimaculoides <strong>an</strong>d O. vulgaris. However, this<br />

colour pattern is evident <strong>in</strong> the rest<strong>in</strong>g coloration <strong>of</strong> T.<br />

mimicus <strong>an</strong>d W. photogenicus only. For all other <strong>octopuses</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> this study, the HCDL pattern is apparent<br />

only <strong>in</strong> the deimatic display (when disturbed). Conspicuously<br />

bold arm b<strong>an</strong>ds may enable the <strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

b<strong>an</strong>ded sea kraits <strong>an</strong>d lionfish by these two <strong>octopuses</strong>,<br />

© 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London, Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77

74 C. L. HUFFARD ET AL.<br />

0.1<br />

<strong>an</strong>d toxic soles by T. mimicus (Norm<strong>an</strong> et al., 2001).<br />

Alternatively, this disruptive pattern may <strong>in</strong>hibit the<br />

ability <strong>of</strong> predators to detect T. mimicus <strong>an</strong>d W. photogenicus<br />

body outl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> their natural habitat: black<br />

s<strong>an</strong>d substrate flecked with white shell fragments.<br />

Correspondence <strong>in</strong> white component size for HDCL<br />

<strong>an</strong>d the substrate should be <strong>an</strong>alysed (as was carried<br />

out for disruptive coloration <strong>in</strong> cuttlefish; H<strong>an</strong>lon<br />

et al., 2009) to assess this possibility. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the<br />

<strong>in</strong>take <strong>an</strong>d subsequent rejection <strong>of</strong> T. mimicus as prey<br />

*<br />

HCDL visible at rest<br />

Flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Arms > 6.5 ML<br />

HCDL <strong>in</strong> deimatic<br />

display<br />

Activity dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

*<br />

* *<br />

*<br />

daylight hours<br />

DVC swimm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Cistopus <strong>in</strong>dicus<br />

Octopus cy<strong>an</strong>ea<br />

Octopus cy<strong>an</strong>ea<br />

Octopus cy<strong>an</strong>ea<br />

Abdopus sp. 1<br />

Abdopus acuelatus<br />

Abdopus "sp. Ward"<br />

"Hawaii<strong>an</strong> Long Armed S<strong>an</strong>d" octopus<br />

"White V" octopus<br />

Wunderpus photogenicus<br />

Thaumoctopus mimicus<br />

Octopus bocki<br />

Octopus oliveri<br />

Octopus sp. 1<br />

Octopus bimaculoides<br />

Octopus vulgaris<br />

Amphioctopus aeg<strong>in</strong>a<br />

Amphioctopus arenicola<br />

Amphioctopus marg<strong>in</strong>atus<br />

Hapalochlaena lunulata<br />

Hapalochlaena fasciata<br />

Hapalochlaena maculosa<br />

Octopus cf. mercatoris<br />

Octopus kaurna<br />

Callistoctopus ornatus<br />

Callistoctopus cf. aspilosomatis<br />

Callistoctopus luteus<br />

Figure 3. Trait distribution <strong>an</strong>d character reconstruction <strong>of</strong> ext<strong>an</strong>t <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>cestral benthic octopodids <strong>in</strong> Figure 2. Grey<br />

bars represent unknown values. Data sources for traits are given <strong>in</strong> Table S2.<br />

by a flounder suggests this octopus may be unpalatable<br />

(Norm<strong>an</strong> & Hochberg, 2006), <strong>an</strong>d that it uses<br />

<strong>conspicuous</strong>ness as a warn<strong>in</strong>g coloration.<br />

IMPERFECT MIMICRY<br />

Mimics that use multiple models may evolve<br />

imperfect <strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>termediate form, rather<br />

th<strong>an</strong> multiple strong resembl<strong>an</strong>ces (Sherratt, 2002).<br />

Thaumoctopus mimicus, ‘White V’, <strong>an</strong>d the ‘Hawaii<strong>an</strong><br />

© 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London, Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77

Long-Armed S<strong>an</strong>d Octopus’ appear to resemble a suite<br />

<strong>of</strong> flatfish rather th<strong>an</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle species [although ‘White<br />

V’ has been suggested to be a high-fidelity mimic <strong>of</strong><br />

Bothus m<strong>an</strong>cus (Broussonet, 1782); H<strong>an</strong>lon et al.<br />

2010]. <strong>The</strong>se <strong>octopuses</strong> <strong>in</strong>habit areas <strong>of</strong> very high<br />

teleost biodiversity, the former two overlapp<strong>in</strong>g<br />

with what appears to be the global epicentre (Roberts<br />

et al., 2002), with numerous potential models <strong>an</strong>d<br />

predators. All three <strong>octopuses</strong> overlap <strong>in</strong> r<strong>an</strong>ge with<br />

the common <strong>an</strong>d similarly coloured B. m<strong>an</strong>cus <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Bothus p<strong>an</strong>ther<strong>in</strong>us (Rüppell, 1830). Accord<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

http://www.fishbase.org, <strong>an</strong> additional 30 nom<strong>in</strong>al<br />

Bothid <strong>an</strong>d Soleidid taxa overlap T. mimicus <strong>an</strong>d<br />

‘White V’ <strong>in</strong> approximate size (> 11 cm total length),<br />

depth (< 50 m), habitat (s<strong>an</strong>d), <strong>an</strong>d possible geographic<br />

r<strong>an</strong>ge with<strong>in</strong> Indonesia. <strong>The</strong>se fishes sp<strong>an</strong> from<br />

<strong>conspicuous</strong> to cryptic, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>in</strong>clude both toxic (e.g.<br />

P. pavon<strong>in</strong>us <strong>an</strong>d potentially Zebrias spp.) <strong>an</strong>d nontoxic<br />

l<strong>in</strong>eages. Although the lack <strong>of</strong> a conclusive flatfish<br />

model has generally been identified as a weakness <strong>in</strong><br />

the cephalopod <strong>mimicry</strong> literature (H<strong>an</strong>lon et al.,<br />

2008), we feel it reflects imperfect <strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>of</strong> multiple<br />

models <strong>in</strong> regions <strong>of</strong> high biodiversity.<br />

Visual defences c<strong>an</strong> be ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed if they are<br />

‘good enough’ to cause pause dur<strong>in</strong>g the speedversus-accuracy<br />

decisions <strong>of</strong> predators: this applies to<br />

imperfect <strong>mimicry</strong> with or without <strong>conspicuous</strong> coloration<br />

(Edmunds, 2000; Chittka & Osorio, 2007).<br />

<strong>The</strong>se decisions may cause enough confusion to allow<br />

‘mimic’ <strong>octopuses</strong> to escape predation. In T. mimicus,<br />

even m<strong>in</strong>or resembl<strong>an</strong>ce to rare toxic models may<br />

further slow reactions <strong>an</strong>d benefit survival. We do<br />

not know how potential unpalatability (Norm<strong>an</strong> &<br />

Hochberg, 2006), perhaps <strong>in</strong> conjunction with arm<br />

autotomy (exhibited by LASO + Abdopus; Norm<strong>an</strong> &<br />

Hochberg, 2006; C. L. Huffard, unpubl. data) may<br />

further contribute to predator confusion, learn<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d/or future avoid<strong>an</strong>ce (Mag<strong>in</strong>nis, 2006). Although<br />

the toxicity <strong>of</strong> T. mimicus (<strong>an</strong>d thus ‘honesty’ <strong>of</strong><br />

a potentially aposematic signal) rema<strong>in</strong>s to be tested,<br />

<strong>conspicuous</strong> flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g appears to be a<br />

secondary adaptation that: (1) follows the concurrent<br />

appear<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> very long arms <strong>an</strong>d a unique mode <strong>of</strong><br />

locomotion; (2) represents a shift towards predator<br />

detection rather th<strong>an</strong> predator avoid<strong>an</strong>ce dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

primary defence <strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong> otherwise cryptic l<strong>in</strong>eage; <strong>an</strong>d<br />

(3) may be re<strong>in</strong>forced if predators c<strong>an</strong> learn from<br />

similar (though cryptically coloured) behaviours <strong>in</strong><br />

sympatric relatives (e.g. Dafni, 1984).<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Permits were obta<strong>in</strong>ed for all collections <strong>in</strong> Australia,<br />

Indonesia, French Polynesia, L<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>an</strong>ds, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Hawaii. Specimens from Thail<strong>an</strong>d were purchased<br />

from a fish market by the 2003 meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the Cepha-<br />

CONSPICUOUS FACULTATIVE MIMICRY IN OCTOPUSES 75<br />

lopod International Advisory Council, <strong>an</strong>d were<br />

identified by Mark Norm<strong>an</strong>. We th<strong>an</strong>k the Palmyra<br />

Atoll Research Consortium, California Academy <strong>of</strong><br />

Sciences, Lizard Isl<strong>an</strong>d Research Station, University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Guam Mar<strong>in</strong>e Station, <strong>an</strong>d University <strong>of</strong> California<br />

Gump Research Station for facilitat<strong>in</strong>g research<br />

activities. John Hoover <strong>an</strong>d Heather Spald<strong>in</strong>g supported<br />

SCUBA activities for collections <strong>in</strong> Hawaii.<br />

Roy Caldwell, Becky Williams, <strong>an</strong>d Chris Bird provided<br />

additional tissue <strong>of</strong> legally collected or purchased<br />

specimens. Photographs were provided by Roy<br />

Caldwell <strong>an</strong>d John Hoover. We are grateful to three<br />

<strong>an</strong>onymous reviewers <strong>an</strong>d Rick W<strong>in</strong>terbottom for<br />

their valuable comments on this m<strong>an</strong>uscript.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Altekar G, Dwarkadas S, Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F.<br />

2004. Parallel metropolis-coupled Markov cha<strong>in</strong> Monte<br />

Carlo for Bayesi<strong>an</strong> phylogenetic <strong>in</strong>ference. Bio<strong>in</strong>formatics<br />

20: 407–415.<br />

Andrews PW, G<strong>an</strong>gestad SW, Matthews D. 2002.<br />

Adaptationism – how to carry out <strong>an</strong> exaptationist program.<br />

Behavioral <strong>an</strong>d Bra<strong>in</strong> Sciences 25: 489–504.<br />

Blackburn DG. 2002. Use <strong>of</strong> phylogenetic <strong>an</strong>alysis to<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>guish adaptation from exaptation. Behavioral <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Bra<strong>in</strong> Sciences 25: 507–508.<br />

Brodie ED III. 1989. Genetic correlations between morphology<br />

<strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>tipredator behavior <strong>in</strong> natural populations <strong>of</strong> the<br />

garter snake Thamnophis ord<strong>in</strong>odes. Nature 342: 542–543.<br />

Carl<strong>in</strong>i DB, Young RE, Vecchione M. 2001. A molecular<br />

phylogeny <strong>of</strong> the Octopoda (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) evaluated<br />

<strong>in</strong> light <strong>of</strong> morphological evidence. Molecular Phylogenetics<br />

<strong>an</strong>d Evolution 21: 388–397.<br />

Chittka L, Osorio D. 2007. Cognitive dimensions <strong>of</strong> predator<br />

responses to imperfect <strong>mimicry</strong>? PLOS Biology 5: e339.<br />

Dafni A. 1984. Mimicry <strong>an</strong>d deception <strong>in</strong> poll<strong>in</strong>ation. Annual<br />

Review <strong>of</strong> Ecology <strong>an</strong>d Systematics 15: 258–278.<br />

Edmunds M. 1974. Defense <strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong>imals. A survey <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>an</strong>ti-predator defenses. New York: Longm<strong>an</strong> Group Limited.<br />

Edmunds M. 2000. Why are there good <strong>an</strong>d poor mimics?<br />

Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society 70: 459–466.<br />

Endler JA. 1981. An overview <strong>of</strong> the relationships between<br />

<strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>an</strong>d crypsis. Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong><br />

Society 16: 25–31.<br />

Gould SJ, Vrba ES. 1982. Exaptation; a miss<strong>in</strong>g term <strong>in</strong> the<br />

science <strong>of</strong> form. Paleobiology 8: 4–15.<br />

Guzik MT, Norm<strong>an</strong> Mark D, Crozier RH. 2005. Molecular<br />

phylogeny <strong>of</strong> the benthic shallow-water <strong>octopuses</strong><br />

(Cephalopoda: Octopod<strong>in</strong>ae). Molecular Phylogenetics &<br />

Evolution 37: 235–248.<br />

H<strong>an</strong>lon RT. 2007. Cephalopod dynamic camouflage. Current<br />

Biology 17: R401–R404.<br />

H<strong>an</strong>lon RT, Messenger JB. 1996. Cephalopod behaviour.<br />

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.<br />

H<strong>an</strong>lon RT, Forsythe JW, Joneschild DE. 1999. Crypsis,<br />

<strong>conspicuous</strong>ness, <strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>an</strong>d polyphenism as <strong>an</strong>tipredator<br />

© 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London, Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77

76 C. L. HUFFARD ET AL.<br />

defences <strong>of</strong> forag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>octopuses</strong> on Indo-Pacific coral reefs,<br />

with a method <strong>of</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>tify<strong>in</strong>g crypsis from video tapes.<br />

Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society 66: 1–22.<br />

H<strong>an</strong>lon RT, Conroy LA, Forsythe J. 2008. Mimicry<br />

<strong>an</strong>d forag<strong>in</strong>g behaviour <strong>of</strong> two tropical s<strong>an</strong>d-flat octopus<br />

species <strong>of</strong>f North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biological Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society 93: 23–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.<br />

2007.00948.x.<br />

H<strong>an</strong>lon RT, Chiao C, Mathger L, Barbosa A, Buresch<br />

KC, Chubb C. 2009. Cephalopod dynamic camouflage:<br />

bridg<strong>in</strong>g the cont<strong>in</strong>uum between background match<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d<br />

disruptive coloration. Philosophical Tr<strong>an</strong>sactions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Royal Society B 364: 429–437.<br />

H<strong>an</strong>lon RT, Watson AC, Barbosa A. 2010. A ‘mimic octopus’<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Atl<strong>an</strong>tic: flatfish <strong>mimicry</strong> <strong>an</strong>d camouflage by<br />

Macrotritopus defilippi. <strong>The</strong> Biological Bullet<strong>in</strong> 218: 15–<br />

24.<br />

Hoover JP. 1998. Hawaii’s sea creatures: a guide to Hawaii’s<br />

mar<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>vertebrates. Honolulu, HI: Mutual Publish<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F, Nielsen R, Bollback JP.<br />

2001. Bayesi<strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong>ference <strong>of</strong> phylogeny <strong>an</strong>d its impact on<br />

<strong>evolution</strong>ary biology. Science 294: 2310–2314.<br />

Huffard CL. 2006. Locomotion by Abdopus aculeatus (Cephalopoda:<br />

Octopodidae): walk<strong>in</strong>g the l<strong>in</strong>e between primary <strong>an</strong>d<br />

secondary defenses. <strong>The</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Experimental Biology<br />

209: 3697–3707.<br />

Huffard CL. 2007. Ethogram <strong>of</strong> Abdopus aculeatus (Cephalopoda:<br />

Octopodidae): c<strong>an</strong> behavioral characters <strong>in</strong>form octopodid<br />

taxonomy <strong>an</strong>d systematics? Journal <strong>of</strong> Mollusc<strong>an</strong><br />

Studies 73: 185–193.<br />

Huffard CL, Boneka F, Full RJ. 2005. Underwater bipedal<br />

locomotion by <strong>octopuses</strong> <strong>in</strong> disguise. Science (Wash<strong>in</strong>gton<br />

DC) 307: 1927.<br />

Hvorecny LM, Grudowski JL, Blakeslee CJ, Simmons<br />

TL, Roy PR, Brooks JA, H<strong>an</strong>ner RM, Beigel ME,<br />

Karson MA, Nichols RH, Holm JB, Boal JG. 2007.<br />

Octopuses (Octopus bimaculoides) <strong>an</strong>d cuttlefishes (Sepia<br />

pharaonis, S. <strong>of</strong>fic<strong>in</strong>alis) c<strong>an</strong> conditionally discrim<strong>in</strong>ate.<br />

Animal Cognition 10: 449–459.<br />

Krajewski JP, Bonaldo RM, Sazima C, Sazima I. 2009.<br />

Octopus mimick<strong>in</strong>g its follower reef fish. Journal <strong>of</strong> Natural<br />

History 43: 185–190.<br />

L<strong>in</strong>dgren AR, Giribet G, Nishiguchi MK. 2004. A comb<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

approach to the phylogeny <strong>of</strong> Cephalopoda (Mollusca).<br />

Cladistics 20: 454–486.<br />

Mag<strong>in</strong>nis TL. 2006. <strong>The</strong> costs <strong>of</strong> autotomy <strong>an</strong>d regeneration<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong>imals: a review <strong>an</strong>d framework for future research.<br />

Behavioral Ecology 17: 857–872.<br />

Marshall NJ, Messenger JB. 1996. Colour-bl<strong>in</strong>d camouflage.<br />

Nature 382: 408–409.<br />

Mart<strong>in</strong>s M, Marques OAV, Sazima I. 2008. How to be<br />

arboreal <strong>an</strong>d diurnal <strong>an</strong>d still stay alive: microhabitat use,<br />

time <strong>of</strong> activity, <strong>an</strong>d defense <strong>in</strong> neotropical forest snakes.<br />

South Americ<strong>an</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Herpetology 3: 58–67.<br />

Mäthger LA, Barbosa A, M<strong>in</strong>er S, H<strong>an</strong>lon RT. 2006.<br />

Color bl<strong>in</strong>dness <strong>an</strong>d contrast perception <strong>in</strong> cuttlefish (Sepia<br />

<strong>of</strong>fic<strong>in</strong>alis) determ<strong>in</strong>ed by a visual sensimotor assay. Vision<br />

Research 46: 1746–1753.<br />

Messenger JB. 2001. Cephalopod chromatophores: neurobiology<br />

<strong>an</strong>d natural history. Biological Reviews 76: 473–<br />

528.<br />

Norm<strong>an</strong> MD. 1992. Octopus cy<strong>an</strong>ea Gray 1849 (Mollusca:<br />

Cephalopoda) <strong>in</strong> Australi<strong>an</strong> Waters: description <strong>an</strong>d taxonomy.<br />

Bullet<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mar<strong>in</strong>e Science 49: 20–38.<br />

Norm<strong>an</strong> MD, F<strong>in</strong>n J. 2001. Revision <strong>of</strong> the Octopus horridus<br />

species-group, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g erection <strong>of</strong> a new subgenus <strong>an</strong>d<br />

description <strong>of</strong> two member species from the Great Barrier<br />

Reef, Australia. Invertebrate Taxonomy 15: 13–35.<br />

Norm<strong>an</strong> MD, Hochberg FG. 2006. <strong>The</strong> ‘Mimic Octopus’<br />

(Thaumoctopus mimicus n. gen. et. sp.), a new octopus from<br />

the tropical Indo-West Pacific (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae).<br />

Mollusc<strong>an</strong> Research 25: 57–70.<br />

Norm<strong>an</strong> MD, F<strong>in</strong>n J, Tregenza T. 2001. Dynamic <strong>mimicry</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong> Indo-Malay<strong>an</strong> octopus. Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> the Royal<br />

Society <strong>of</strong> London – Series B: Biological Sciences 268: 1755–<br />

1758.<br />

Nyl<strong>an</strong>der JAA. 2004. Mrmodeltest v2. Program distributed<br />

by the author. Uppsala University: Evolutionary Biology<br />

Centre.<br />

Packard A. 1972. Cephalopods <strong>an</strong>d fish: the limits <strong>of</strong> converg<strong>an</strong>ce.<br />

Biological Reviews <strong>of</strong> the Cambridge Philosophical<br />

Society (London) 47: 241–307.<br />

Roberts CM, McCle<strong>an</strong> CJ, Veron JEN, Hawk<strong>in</strong>s JP,<br />

Allen GR, McAllister DE, Mittermeier CG, Schueler<br />

FW, Spald<strong>in</strong>g M, Wells F, Vynne C, Werner TB. 2002.<br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>e Biodiversity Hotspots <strong>an</strong>d Conservation Priorities<br />

for Tropical Reefs. Science 295: 1280–1284.<br />

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. 2003. MRBAYES 3: Bayesi<strong>an</strong><br />

phylogenetic <strong>in</strong>ference under mixed models. Bio<strong>in</strong>formatics<br />

19: 1572–1574.<br />

Sherratt TN. 2002. <strong>The</strong> <strong>evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> imperfect <strong>mimicry</strong>.<br />

Behavioral Ecology 13: 821–826.<br />

Sw<strong>of</strong>ford DL. 2002. Paup*. Phylogenetic <strong>an</strong>alysis us<strong>in</strong>g parsimony<br />

(*<strong>an</strong>d other methods). Version 4.0b10. Sunderl<strong>an</strong>d,<br />

MA: S<strong>in</strong>auer Associates.<br />

Sword GA. 2002. A role for phenotypic plasticity <strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> aposematism. Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> the Royal Society<br />

B: Biological Sciences 269: 1639–1644.<br />

Wells MJ. 1990. Oxygen extraction <strong>an</strong>d jet propulsion<br />

<strong>in</strong> Cephalopods. C<strong>an</strong>adi<strong>an</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Zoology 68: 815–<br />

824.<br />

Wells MJ, Duthie GG, Houlih<strong>an</strong> DF, Smith PJS. 1987.<br />

Blood flow <strong>an</strong>d pressure ch<strong>an</strong>ges <strong>in</strong> exercis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>octopuses</strong><br />

Octopus vulgaris. Journal <strong>of</strong> Experimental Biology 131:<br />

175–187.<br />

W<strong>in</strong>terbottom R, McLenn<strong>an</strong> DA. 1993. Cladogram versatility:<br />

<strong>evolution</strong> <strong>an</strong>d biogeography <strong>of</strong> Ac<strong>an</strong>thurid fishes.<br />

Evolution 47: 1557–1571.<br />

© 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London, Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77

CONSPICUOUS FACULTATIVE MIMICRY IN OCTOPUSES 77<br />

SUPPORTING INFORMATION<br />

Additional Support<strong>in</strong>g Information may be found <strong>in</strong> the onl<strong>in</strong>e version <strong>of</strong> this article:<br />

Table S1. GenB<strong>an</strong>k accession numbers, collection localities (newly <strong>an</strong>alysed), <strong>an</strong>d references (previous studies)<br />

for the samples used <strong>in</strong> this study.<br />

Table S2. Behavioural <strong>an</strong>d morphological traits for samples species. Order reflects top-bottom order <strong>of</strong> these<br />

taxa <strong>in</strong> Figure 3. A = Absent, D = Activity dur<strong>in</strong>g daylight reported, N = Nocturnal, P = Present; U = Unknown;<br />

Very long-arms (> 6.5 ¥ ML) <strong>in</strong> bold. Sources: 1) Norm<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Sweeney (1997); 2) H<strong>an</strong>lon <strong>an</strong>d Messenger (1996);<br />

3) Yarnall, 1969; 4) Forsythe <strong>an</strong>d H<strong>an</strong>lon (1997); 5) CLH unpublished data; 6) CLH personal observations <strong>in</strong><br />

situ; 7) Norm<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d F<strong>in</strong>n (2001); 8) Huffard (2007); 9) Huffard (2006); 10) Ward, 1998); 11) Hoover, 1998; 12)<br />

H<strong>an</strong>lon et al., 2008; 13) Norm<strong>an</strong>, 2000; 14) Hochberg et al., 2006; 15) Norm<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Hochberg, 2005; 16) CLH<br />

personal observations <strong>in</strong> aquaria; 17) Cheng, 1996; 18) Packard <strong>an</strong>d S<strong>an</strong>ders, 1971; 19) Kayes, 1974; 20) Huffard<br />

<strong>an</strong>d Hochberg 2005; 21) Norm<strong>an</strong>, 1993; 22) Norm<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Hochberg unpublished data. 23) Roy Caldwell personal<br />

observations <strong>in</strong> aquaria; 24) Toll, 1998.<br />

Video S1. Dorsoventrally compressed swimm<strong>in</strong>g, but not flatfish swimm<strong>in</strong>g, by Wunderpus photogenicus.<br />

Appendix S1. DNA isolation, amplification, <strong>an</strong>d sequenc<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Appendix S2. MrBayes comm<strong>an</strong>d blocks.<br />

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong>y support<strong>in</strong>g materials<br />

supplied by the authors. Any queries (other th<strong>an</strong> miss<strong>in</strong>g material) should be directed to the correspond<strong>in</strong>g<br />

author for the article.<br />

© 2010 <strong>The</strong> L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> London, Biological Journal <strong>of</strong> the L<strong>in</strong>ne<strong>an</strong> Society, 2010, 101, 68–77