the anorexic tortoise - BSAVA

the anorexic tortoise - BSAVA

the anorexic tortoise - BSAVA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

How to approach<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>anorexic</strong><br />

<strong>tortoise</strong><br />

John Chitty, who runs<br />

<strong>the</strong> exotics service at<br />

Anton Vets, helps us<br />

tackle a challenging<br />

topic<br />

Anorexia is probably <strong>the</strong> most<br />

common presenting sign for<br />

<strong>tortoise</strong>s seen in veterinary<br />

practice. In some cases patients<br />

are overtly unwell; in o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>the</strong> animal<br />

still seems bright; and some will be in<br />

between, appearing ‘just a little slow’<br />

to <strong>the</strong>ir owners.<br />

In an article such as this it is important<br />

to define some of <strong>the</strong> terms used:<br />

■■ Tortoise. For <strong>the</strong> purposes of this<br />

article a <strong>tortoise</strong> is one of <strong>the</strong> Testudo<br />

group of Mediterranean/Middle<br />

Eastern <strong>tortoise</strong>s – <strong>the</strong> Spur-thighed<br />

group; Hermann’s: marginated; and<br />

Horsfield’s <strong>tortoise</strong>s: <strong>the</strong>se are <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tortoise</strong>s most commonly kept as pets<br />

in <strong>the</strong> UK. With <strong>the</strong> exception of some<br />

North African spur-thighed <strong>tortoise</strong>s,<br />

<strong>the</strong> majority will hibernate. All are<br />

herbivorous and terrestrial.<br />

■■ Anorexia. Literally means lack of, or<br />

reduced appetite. However, reptiles do<br />

not always eat every day, especially<br />

when breeding or immediately before/<br />

after hibernation. Therefore it is<br />

important to determine whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong><br />

anorexia is persistent and significant or<br />

a single occurrence. It is necessary to<br />

investigate fur<strong>the</strong>r if:<br />

– ■ There is concurrent weight loss.<br />

– ■ There are any o<strong>the</strong>r signs of ill<br />

health, including lethargy.<br />

– ■ The <strong>tortoise</strong> has not eaten for over a<br />

12 | companion<br />

week. If less than a week and <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tortoise</strong> appears well, advise<br />

owners to keep <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong> warm<br />

(25–35°C in <strong>the</strong> day: 20–25°C at<br />

night), ba<strong>the</strong> it daily in plain warm<br />

water for 10–15 minutes and<br />

monitor bodyweight daily.<br />

Post-hibernation anorexia is not a<br />

specific condition. Anorexia is common<br />

during this period mainly because this is a<br />

time of maximal metabolic stress in <strong>the</strong><br />

animal and because UK wea<strong>the</strong>r can be<br />

particularly variable in Spring (for this<br />

reason, it is also common to see <strong>anorexic</strong><br />

animals in Autumn too). In any event, <strong>the</strong><br />

diagnostic investigation of <strong>the</strong> <strong>anorexic</strong><br />

<strong>tortoise</strong> is largely <strong>the</strong> same whatever <strong>the</strong><br />

time of year.<br />

With such a wide range of differentials<br />

(Table 1) it is vital that a full assessment is<br />

carried out in all cases. The old posthibernation<br />

injection of B-vitamins really is<br />

not enough!<br />

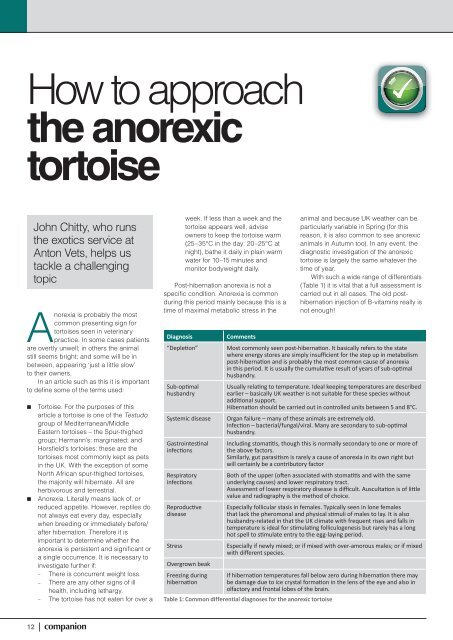

Diagnosis Comments<br />

“Depleti on” Most commonly seen post-hibernati on. It basically refers to <strong>the</strong> state<br />

where energy stores are simply insuffi cient for <strong>the</strong> step up in metabolism<br />

post-hibernati on and is probably <strong>the</strong> most common cause of anorexia<br />

in this period. It is usually <strong>the</strong> cumulati ve result of years of sub-opti mal<br />

husbandry.<br />

Sub-opti mal<br />

husbandry<br />

Usually relati ng to temperature. Ideal keeping temperatures are described<br />

earlier – basically UK wea<strong>the</strong>r is not suitable for <strong>the</strong>se species without<br />

additi onal support.<br />

Hibernati on should be carried out in controlled units between 5 and 8°C.<br />

Systemic disease Organ failure – many of <strong>the</strong>se animals are extremely old.<br />

Infecti on – bacterial/fungal/viral. Many are secondary to sub-opti mal<br />

husbandry.<br />

Gastrointesti nal<br />

infecti ons<br />

Respiratory<br />

infecti ons<br />

Reproducti ve<br />

disease<br />

Including stomati ti s, though this is normally secondary to one or more of<br />

<strong>the</strong> above factors.<br />

Similarly, gut parasiti sm is rarely a cause of anorexia in its own right but<br />

will certainly be a contributory factor<br />

Both of <strong>the</strong> upper (oft en associated with stomati ti s and with <strong>the</strong> same<br />

underlying causes) and lower respiratory tract.<br />

Assessment of lower respiratory disease is diffi cult. Auscultati on is of litt le<br />

value and radiography is <strong>the</strong> method of choice.<br />

Especially follicular stasis in females. Typically seen in lone females<br />

that lack <strong>the</strong> pheromonal and physical sti muli of males to lay. It is also<br />

husbandry-related in that <strong>the</strong> UK climate with frequent rises and falls in<br />

temperature is ideal for sti mulati ng folliculogenesis but rarely has a long<br />

hot spell to sti mulate entry to <strong>the</strong> egg-laying period.<br />

Stress Especially if newly mixed; or if mixed with over-amorous males; or if mixed<br />

with diff erent species.<br />

Overgrown beak<br />

Freezing during If hibernati on temperatures fall below zero during hibernati on <strong>the</strong>re may<br />

hibernati on<br />

be damage due to ice crystal formati on in <strong>the</strong> lens of <strong>the</strong> eye and also in<br />

olfactory and frontal lobes of <strong>the</strong> brain.<br />

Table 1: Common differential diagnoses for <strong>the</strong> <strong>anorexic</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong>

Figure 1: A male Hermann’s <strong>tortoise</strong> – note <strong>the</strong><br />

long keratinised end to <strong>the</strong> tail<br />

Clinical assessment<br />

A full history should be taken. This should<br />

concentrate on:<br />

■■ Signalment – unlike in dogs and cats<br />

this is rarely known. Most owners can<br />

say how long <strong>the</strong>y have had <strong>the</strong> animal<br />

but can rarely give more than an<br />

indication of age. If owned for many<br />

years it is worth asking if <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong><br />

has grown in that time. If it has grown<br />

significantly <strong>the</strong>n likely it was young<br />

when first owned. If not, <strong>the</strong>n it was<br />

probably mature when first owned. With<br />

<strong>the</strong>se species physical maturity would<br />

probably suggest that <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong> was<br />

at least 20 years old when acquired.<br />

The species of <strong>tortoise</strong> is also not<br />

always known and it is worth being<br />

familiar with <strong>the</strong> common species in<br />

this group. Sex is often determined by<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r or not <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong> has laid<br />

eggs or not. This is not always reliable!<br />

While Hermann’s and Horsfield’s are<br />

relatively easy to sex (males have much<br />

longer tails – Figure 1) <strong>the</strong> spur-thighed<br />

group can be very hard to sex. Shell<br />

shapes can be useful but are unreliable<br />

in captive-bred animals as <strong>the</strong>re are so<br />

many diet-induced abnormalities.<br />

Familiarity is <strong>the</strong> key!<br />

■■ Husbandry. Full details are required:<br />

– ■ Hibernation times and manner.<br />

– ■ Temperature provision if any;<br />

temperature measurements and<br />

how <strong>the</strong>se are are performed –<br />

remember that a <strong>the</strong>rmostat is a<br />

control device not an accurate<br />

measure of temperature.<br />

– ■ If housed, vivarium or tray? Is <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tortoise</strong> kept outside?<br />

– ■ Humidity (Mediterranean <strong>tortoise</strong>s<br />

generally require a dry environment).<br />

– ■ Diet and feeding history.<br />

– ■ Bathing?<br />

– ■ Weight history. Many owners keep<br />

accurate records of <strong>the</strong> animal’s<br />

weight, especially before and after<br />

hibernation. These data are very<br />

valuable.<br />

– ■ Contact with o<strong>the</strong>r animals,<br />

especially o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>tortoise</strong> species.<br />

■■ Medical history.<br />

■■ Urination/defecation: absence of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se (especially if being ba<strong>the</strong>d) is<br />

significant.<br />

■■ Reaction to food – is <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong><br />

interested?<br />

■■ Activity levels.<br />

■■ Respiratory noise.<br />

Before handling, <strong>the</strong> respiratory pattern<br />

should be assessed. In most <strong>tortoise</strong>s<br />

breaths are infrequent and may be hard to<br />

detect. However, if <strong>the</strong>re is overt respiratory<br />

effort, open-mouth breathing, or excessive<br />

vocalisation on breathing <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>se may<br />

be indicators of severe disease. Do not<br />

confuse aggressive hissing with respiratory<br />

noise, nor gular pumping (throat<br />

movements) with respiratory movements.<br />

A thorough clinical examination should<br />

be performed. However, <strong>the</strong> presence of<br />

<strong>the</strong> shell severely limits what can be<br />

examined. All patients should be weighed<br />

and this weight compared to any previously<br />

recorded weights and, most importantly,<br />

with <strong>the</strong> animal’s current body condition.<br />

Body condition is assessed by <strong>the</strong><br />

amount of fat pad present in <strong>the</strong> prefemoral<br />

fossa and between forelimbs and<br />

neck. Sunken eyes may be a sign of<br />

dehydration, but may also indicate a loss of<br />

<strong>the</strong> fat pad behind <strong>the</strong> eyes.<br />

The Jackson ratio (a graphical<br />

comparison of weight:length allowing<br />

assessment of ideal condition) may be of<br />

some use for medium-sized spur-thighed<br />

and Hermann’s <strong>tortoise</strong>s, but generally is of<br />

limited value compared to body condition<br />

assessment – for example a <strong>tortoise</strong><br />

containing many eggs will have a good<br />

Jackson “score” even though it may be<br />

very thin.<br />

The eyes should be assessed for<br />

opacities and swelling of lids,<br />

conjunctiva, etc.<br />

The nares should be checked for<br />

discharges, abscessation, etc.<br />

The mouth should be carefully<br />

assessed (Figure 2) for:<br />

Figure 2: Oral examination – note normal<br />

membrane colour and texture<br />

companion | 13

14 | companion<br />

How to approach <strong>the</strong> <strong>anorexic</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong><br />

■■ Mucous membrane colour. Some<br />

yellowing may be normal in <strong>the</strong><br />

post-hibernation period. Cyanosis<br />

potentially indicates respiratory disease.<br />

■■ Dry sticky membranes – may show<br />

severe dehydration.<br />

■■ Presence of purulent or diph<strong>the</strong>ritic<br />

material.<br />

■■ Foreign bodies within <strong>the</strong> choana<br />

(passage in roof of mouth to nasal<br />

chamber).<br />

Limbs should be checked for swellings<br />

and it is useful to see <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong> walk,<br />

though this is not always possible.<br />

The cloaca should be examined as<br />

much as possible, in particular for<br />

discharges and ulceration.<br />

The shell should be assessed for<br />

damage or infection. In septicaemia<br />

<strong>the</strong>re may be a reddening of parts of <strong>the</strong><br />

shell. This will “blanch” when pressed with<br />

a fingernail.<br />

The skin may be checked for<br />

ulceration, flakiness or o<strong>the</strong>r lesions.<br />

Tenting of <strong>the</strong> skin is not a reliable indicator<br />

of dehydration.<br />

Limited palpation of <strong>the</strong> abdomen<br />

may be performed by placing fingers in<br />

<strong>the</strong> prefemoral fossae and gently<br />

rocking <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong> side-to-side.<br />

Large masses or eggs may bump<br />

against <strong>the</strong> fingers.<br />

The heart may be auscultated using<br />

a 8MHz Doppler device (as used for<br />

measuring feline blood pressure) placed<br />

on <strong>the</strong> skin between forelimb and neck.<br />

Harsh murmurs may be an indication<br />

of endocarditis.<br />

Sample taking<br />

Clinical findings will dictate which<br />

samples are taken. However, a blood<br />

sample is essential in nearly all cases in<br />

order to assess underlying disease, fluid<br />

and electrolyte balance, nutritional status<br />

and immune status and inflammatory<br />

status. Without sampling it is nearly<br />

impossible to assess hydration and<br />

feeding needs adequately.<br />

Table 2 details <strong>the</strong> parameters<br />

evaluated in blood analysis of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

patients. Some tests are performed patientside,<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs by a diagnostic laboratory.<br />

Most laboratories will be able to assess<br />

<strong>the</strong>se on approx 1 ml heparinised blood<br />

(haematology is performed on blood taken<br />

into heparin not EDTA) and two fresh blood<br />

smears, however <strong>the</strong>y should be consulted<br />

prior to sampling to check <strong>the</strong>ir needs and<br />

also which parameters <strong>the</strong>y include in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

profiles. Blood samples may be taken from<br />

jugular, subcarapacial (Figure 3) or tail<br />

veins. It is always worth stating on<br />

submission forms which sampling site has<br />

been used, as <strong>the</strong>re is a much higher<br />

incidence of lymphodilution from <strong>the</strong> tail<br />

vein. Where obvious lymphodilution<br />

occurs, <strong>the</strong> sample should be discarded.<br />

Interpretation of blood parameters<br />

(Table 2) can be very difficult. Not only do<br />

individual labs and machines vary in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

reference intervals, but <strong>the</strong>re may be<br />

differences between species and certainly<br />

Figure 3: Sampling from subcarapacial vein – a<br />

bent needle is inserted in <strong>the</strong> dorsal midline<br />

approximately where skin joins shell<br />

major differences in individual parameters<br />

through <strong>the</strong> annual cycle. It is very<br />

important to use laboratories with<br />

experienced consultants to assist in such<br />

interpretation – to this end a thorough<br />

written history and as accurate a<br />

signalment as possible should accompany<br />

each case submission.<br />

Parameter Notes<br />

Haematology Full haematology – red and white cell parameters. Oft en <strong>the</strong> cell counts are<br />

of lesser importance than cell morphology which is why an experienced<br />

“exoti cs” haematologist should always be consulted.<br />

Urea See Table 3.<br />

Uric acid See Table 3. Also a useful assessment of renal disease. Levels >1000 µmol/l<br />

indicati ve of renal disease: >2500 µmol/l grave prognosis.<br />

Electrolytes Sodium, potassium, ionised calcium. Potassium levels >5 mmol/l are<br />

signifi cant; >9 mmol/l grave prognosis. These should be measured<br />

pati entside or a spun heparin gel tube should also be supplied. O<strong>the</strong>rwise<br />

post-sampling changes may arti fi cially raise potassium levels.<br />

Total calcium and Not as useful in assessment of renal disease as in iguanas, but of use in<br />

phosphate assessing reproducti ve functi on in females (Box 1).<br />

Glucose Measure pati entside – immediate assessment of nutriti onal status/depleti on.<br />

Beta-<br />

Ketosis.<br />

Hydroxybutyrate<br />

Liver enzymes AST, CK, GLDH and GGT may all be assessed. These allow some assessment<br />

of hepatocellular damage and ti ssue damage. However, none is sensiti ve nor<br />

specifi c and it is hard to assess liver disease in chelonians. Biliverdinuria is a<br />

more specifi c indicator, though not sensiti ve.<br />

Bile acids Can be hard to assess unless extremely high.<br />

Proteins Albumin, globulins and rati o. Assessment of protein balance and<br />

infl ammatory responses. Electrophoresis may be helpful in <strong>the</strong> latt er case.<br />

Table 2: Parameters to be included in an <strong>anorexic</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong> blood panel

Parameter Comments<br />

Skin tenting Hard to assess and a very insensitive measure.<br />

Mucous membranes Dry sticky membranes more sensitive than skin tenting.<br />

Haemoconcentration In <strong>the</strong>ory, raised albumin and haematocrit should accompany<br />

dehydration. However, most of <strong>the</strong>se <strong>tortoise</strong>s will have varying degrees<br />

of hypoalbuminaemia and anaemia (due to underlying disease/debility/<br />

anorexia) that such an interpretation is confounded.<br />

Uric acid Will rise in dehydration. However, will also rise in renal disease.<br />

Urea These species use <strong>the</strong> urinary bladder as a water store. Accessing this<br />

allows smaller molecules, including urea, to enter <strong>the</strong> bloodstream – i.e.<br />

urea is a measure of degree of access to stores. The higher <strong>the</strong> level of<br />

urea, <strong>the</strong> greater <strong>the</strong> dehydration. It is unaffected by renal disease (except<br />

in severe disease) so is an extremely important indicator of hydration.<br />

Table 3: Assessment of dehydration in <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong><br />

BOX 1: Markers of reproductive function in female <strong>tortoise</strong>s<br />

The following parameters may all rise in <strong>the</strong> reproductively active female:<br />

■■ Protein – total/albumin/globulin<br />

■■ Total calcium<br />

■■ Phosphate – Calcium:phosphate ratio usually remains in normal range<br />

■■ AST/ALKP/CK<br />

■■ Cholesterol/triglyceride<br />

NB: This “pattern” is not a marker for reproductive disease or follicular stasis unless such<br />

levels remain high and <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong> is not recovering. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, it indicates a need to assess <strong>the</strong><br />

reproductive system via radiography/ultrasonography.<br />

Follicular stasis is diagnosed by a persistent:<br />

■■ Reproductive blood picture<br />

■■ Ovarian follicles – <strong>the</strong>se show no evidence of atresia nor progression to egg<br />

Test Comments Indication<br />

Faecal analysis May be hard to obtain! Worth<br />

bathing daily to twice daily to<br />

stimulate defecation. Fresh (

Apart from <strong>the</strong> very mildest cases, it is<br />

highly unlikely this can be provided at<br />

home, so almost all cases will require<br />

hospitalisation. As husbandry problems<br />

started at home, out-patient <strong>the</strong>rapy is<br />

unlikely to be successful.<br />

Hospitalisation is usually 5–14 days for<br />

<strong>the</strong> average case. Therefore a practice<br />

treating <strong>the</strong>se species will need specific<br />

facilities. This may vary from a heat lamp in<br />

a kennel for <strong>the</strong> occasional case, to vivaria<br />

or <strong>tortoise</strong> trays where <strong>the</strong>re is a greater<br />

caseload (Figure 5).<br />

Again, important biological parameters,<br />

especially temperature should be<br />

measured and maintained at correct levels<br />

in hospital (Figure 6). Half measures will<br />

not suffice and result in more unsuccessful<br />

cases and frustrated owners.<br />

It is vital that owner education is a part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> treatment plan. This is especially<br />

important for older <strong>tortoise</strong>s as owners do<br />

not see why <strong>the</strong>re is a problem now with<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir husbandry when <strong>the</strong>re had been no<br />

issues over <strong>the</strong> previous thirty-odd years!<br />

However, reluctance to change husbandry<br />

will simply result in relapsing cases. A<br />

frequent finding with inadequate home<br />

temperatures is that <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong> will do well<br />

for 48 hours following discharge and <strong>the</strong>n<br />

stop eating: some research suggests<br />

reptiles can maintain internal temperatures<br />

for up to 2 days!<br />

16 | companion<br />

How to approach <strong>the</strong> <strong>anorexic</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong><br />

A B Figure 7: Daily bathing is vital. It also helps<br />

Figure 5: Hospitalisation units. Vivaria are a typical means of housing all reptiles. They have,<br />

erroneously, gained a reputation as a cause of respiratory disease in <strong>tortoise</strong>s due to high humidity.<br />

However, this can be controlled as well as temperature. Trays are excellent means of hospitalising<br />

<strong>tortoise</strong>s but rely on a high background room temperature as it is this that sets crucial minimum<br />

temperatures. The author’s unit uses combined ultra-violet and heat sources as basking points<br />

Figure 6: Digital maximum–minimum<br />

<strong>the</strong>rmometers are easily available and <strong>the</strong>se<br />

units with two probes are inexpensive. This<br />

photo shows minimum values that should be<br />

achieved in <strong>the</strong> hospitalised setting. If using<br />

vivaria, <strong>the</strong>y should be insulated to achieve<br />

<strong>the</strong>se temperatures. If using trays, room<br />

temperature needs controlling to <strong>the</strong>se levels<br />

While hospitalised, all cases will require<br />

basic supportive care.<br />

Rehydration<br />

All <strong>tortoise</strong>s should be ba<strong>the</strong>d daily in plain<br />

warm water or in a glucose/electrolyte mix<br />

(e.g. Reptoboost (Vetark, Winchester UK)).<br />

For mildly dehydrated animals this may be<br />

sufficient to restore fluid balance. Bathing<br />

will also help to stimulate urination/<br />

defecation (Figure 7).<br />

stimulate defecation/urination (see <strong>tortoise</strong> on<br />

left). Biosecurity is vital – all equipment should<br />

be labelled (in this case bath numbers match<br />

tray numbers) so no fomite transfer occurs<br />

between in-patients<br />

For more severe cases, fluids may be<br />

given:<br />

■■ Oral fluids – Hypotonic fluids (including<br />

plain water!) may be given by gavage<br />

tube. Around 20ml/kg in single or<br />

divided doses (Figure 8).<br />

■■ Intra- or epi-coelomic (Figure 9) – Up to<br />

30 ml/kg once daily of isotonic fluid.<br />

■■ Intra-osseous – Needles may be<br />

placed into <strong>the</strong> femur or humerus, or<br />

Figure 8: Gavage tubing a <strong>tortoise</strong>. The neck is<br />

held straight and <strong>the</strong> tube gently inserted down<br />

<strong>the</strong> oesophagus

Figure 9: Epi-coelomic fluid injection into <strong>the</strong><br />

prefemoral fossa<br />

<strong>the</strong> bridge of <strong>the</strong> shell between <strong>the</strong><br />

plastron and carapace. Isotonic fluids<br />

are given at approx 30 ml/kg/day and a<br />

syringe driver or Springfusor pump is<br />

required for administration.<br />

Fluid choice for systemic <strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

depends on electrolyte assessment.<br />

Critical nutrition<br />

It is important to stimulate eating as<br />

quickly as possible. To this end, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tortoise</strong>’s favourite foods should be<br />

ascertained and offered.<br />

Where <strong>the</strong>re is no particular favourite,<br />

this author offers a standard salad mix<br />

(lettuce/cucumber/tomato) with<br />

strawberries and dandelions whenever<br />

available. This is not a balanced diet and<br />

vitamin supplementation is not offered as<br />

many <strong>tortoise</strong>s do not like <strong>the</strong>se. Once <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tortoise</strong> is eating well, <strong>the</strong> diet can be<br />

amended to a more healthy one.<br />

Those cases that are suspected of<br />

being blind and/or cold-damaged should<br />

be hand-fed especially if <strong>the</strong>y actively<br />

appear interested in food.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>rwise critical nutrition is provided<br />

by gavage tube. Initially, simple<br />

carbohydrate mixes (e.g. Critical Care<br />

Formula (Vetark, Winchester, UK) or Liquid<br />

Lifeade (Norbrook, Carlisle, UK))<br />

progressing to higher fibre formulas in<br />

herbivores (e.g. Oxbow Fine Grind (Oxbow,<br />

Nebraska, USA), Emeraid Herbivore<br />

(Lafeber, USA)). Formulas for carnivores<br />

should be avoided.<br />

Animals that are difficult to tube, will<br />

require long-term tubing or have sufficiently<br />

good husbandry to be treated at home can<br />

be fed by means of an oesophagostomy<br />

tube. This should be fitted under sedation<br />

or local anaes<strong>the</strong>sia (depending on level of<br />

debility) in much <strong>the</strong> same way as in a cat.<br />

Antibiotic <strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

Broad-spectrum “cover” is required in all<br />

<strong>tortoise</strong>s with extremely low white cell<br />

counts or those showing an active<br />

inflammatory response. Where <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

identifiable lesions (e.g. stomatitis,<br />

pneumonia), drug choice should be<br />

based on culture and sensitivity of<br />

collected samples.<br />

Where <strong>the</strong>re are no obvious lesions,<br />

fluoroquinolones or ceftazidime may be<br />

used empirically. Care should be taken not<br />

to select very irritant drugs for long-term<br />

intramuscular administration. If long-term<br />

use is needed, <strong>the</strong>n ei<strong>the</strong>r a less irritant<br />

drug should be used or <strong>the</strong> medication<br />

switched to oral dosing as soon as <strong>the</strong><br />

clinician is sure gut absorption is optimal.<br />

Monitoring<br />

Where <strong>the</strong> <strong>tortoise</strong> is clearly improving<br />

clinically (appears stronger, eating,<br />

urinating/defecating, etc.) and continues to<br />

do well at home, <strong>the</strong>re is rarely a need to<br />

do more than physical checks.<br />

However, for animals that ei<strong>the</strong>r showed<br />

severe abnormalities on initial blood<br />

sampling or that are showing little or no<br />

response to <strong>the</strong>rapy, repeat blood sampling<br />

at 7–10-day intervals is a very good means<br />

of assessing progress and prognosis.<br />

Prevention<br />

It is clear that <strong>the</strong> key to avoiding anorexia<br />

is maintenance of good husbandry.<br />

Traditional means of keeping <strong>tortoise</strong>s in<br />

<strong>the</strong> UK, combined with <strong>the</strong> older methods<br />

of hibernation (such as a box of hay in<br />

garage/shed/loft), are simply not adequate<br />

and as animals get older <strong>the</strong>y will succumb.<br />

For lone females, access to healthy<br />

males of <strong>the</strong> same species in May and<br />

June each year may assist in avoiding<br />

follicular stasis.<br />

Good advice on husbandry is now<br />

available from many sources, including<br />

<strong>the</strong> British Chelonia Group and The<br />

Tortoise Trust.<br />

It is also worthwhile carrying out<br />

regular health checks to assess weight and<br />

condition pre- and post-hibernation. This<br />

can be combined with endoparasite<br />

control and ultrasound scanning of females<br />

to monitor ovarian activity.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> author’s practice most checks are<br />

done at twice yearly “parties” for “healthy”<br />

<strong>tortoise</strong>s. This enables not only <strong>the</strong> clinical<br />

check, but also allows interested owners to<br />

meet and exchange tips and techniques. It<br />

is also a very good way for <strong>the</strong> lone females<br />

with follicular stasis to meet males – speed<br />

dating for <strong>tortoise</strong>s!<br />

Conclusion<br />

Modern <strong>tortoise</strong> keeping recognises that<br />

<strong>tortoise</strong>s are reptiles and that <strong>the</strong>ir keeping<br />

requires levels of biological support as<br />

does keeping snakes and lizards.<br />

The difficulty for <strong>the</strong> practitioner is that<br />

many Mediterranean <strong>tortoise</strong>s have coped<br />

with <strong>the</strong> British climate for many years,<br />

giving <strong>the</strong> illusion that <strong>the</strong>se animals do not<br />

need such support. To overcome this, vets<br />

seeing <strong>the</strong>se animals must communicate<br />

well to educate <strong>the</strong> “traditional” keeper and<br />

demonstrate such standards in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

hospitalisation and treatment. ■<br />

companion | 17