BERNARD HERRMANN - Film Noir Foundation

BERNARD HERRMANN - Film Noir Foundation

BERNARD HERRMANN - Film Noir Foundation

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

His career encompassed radio, film, television, and the concert<br />

hall. The cinematic genres in which he worked ranged from traditional<br />

drama to fantasy to science fiction. But the composer, whose<br />

centenary is being celebrated worldwide this year with film festivals<br />

and concerts, remains best known for scores that explore the darkest<br />

side of human nature. Many intersect with the themes and obsessions<br />

of noir.<br />

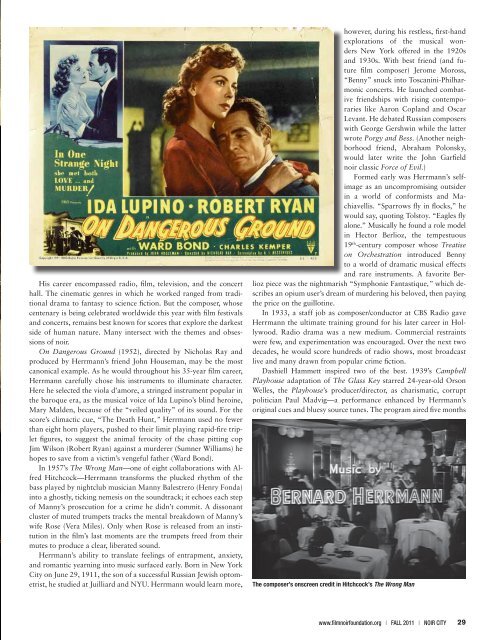

On Dangerous Ground (1952), directed by Nicholas Ray and<br />

produced by Herrmann’s friend John Houseman, may be the most<br />

canonical example. As he would throughout his 35-year film career,<br />

Herrmann carefully chose his instruments to illuminate character.<br />

Here he selected the viola d’amore, a stringed instrument popular in<br />

the baroque era, as the musical voice of Ida Lupino’s blind heroine,<br />

Mary Malden, because of the “veiled quality” of its sound. For the<br />

score’s climactic cue, “The Death Hunt,” Herrmann used no fewer<br />

than eight horn players, pushed to their limit playing rapid-fire triplet<br />

figures, to suggest the animal ferocity of the chase pitting cop<br />

Jim Wilson (Robert Ryan) against a murderer (Sumner Williams) he<br />

hopes to save from a victim’s vengeful father (Ward Bond).<br />

In 1957’s The Wrong Man—one of eight collaborations with Alfred<br />

Hitchcock—Herrmann transforms the plucked rhythm of the<br />

bass played by nightclub musician Manny Balestrero (Henry Fonda)<br />

into a ghostly, ticking nemesis on the soundtrack; it echoes each step<br />

of Manny’s prosecution for a crime he didn’t commit. A dissonant<br />

cluster of muted trumpets tracks the mental breakdown of Manny’s<br />

wife Rose (Vera Miles). Only when Rose is released from an institution<br />

in the film’s last moments are the trumpets freed from their<br />

mutes to produce a clear, liberated sound.<br />

Herrmann’s ability to translate feelings of entrapment, anxiety,<br />

and romantic yearning into music surfaced early. Born in New York<br />

City on June 29, 1911, the son of a successful Russian Jewish optometrist,<br />

he studied at Juilliard and NYU. Herrmann would learn more,<br />

however, during his restless, first-hand<br />

explorations of the musical wonders<br />

New York offered in the 1920s<br />

and 1930s. With best friend (and future<br />

film composer) Jerome Moross,<br />

“Benny” snuck into Toscanini-Philharmonic<br />

concerts. He launched combative<br />

friendships with rising contemporaries<br />

like Aaron Copland and Oscar<br />

Levant. He debated Russian composers<br />

with George Gershwin while the latter<br />

wrote Porgy and Bess. (Another neighborhood<br />

friend, Abraham Polonsky,<br />

would later write the John Garfield<br />

noir classic Force of Evil.)<br />

Formed early was Herrmann’s selfimage<br />

as an uncompromising outsider<br />

in a world of conformists and Machiavellis.<br />

“Sparrows fly in flocks,” he<br />

would say, quoting Tolstoy. “Eagles fly<br />

alone.” Musically he found a role model<br />

in Hector Berlioz, the tempestuous<br />

19 th -century composer whose Treatise<br />

on Orchestration introduced Benny<br />

to a world of dramatic musical effects<br />

and rare instruments. A favorite Berlioz<br />

piece was the nightmarish “Symphonie Fantastique,” which describes<br />

an opium user’s dream of murdering his beloved, then paying<br />

the price on the guillotine.<br />

In 1933, a staff job as composer/conductor at CBS Radio gave<br />

Herrmann the ultimate training ground for his later career in Hollywood.<br />

Radio drama was a new medium. Commercial restraints<br />

were few, and experimentation was encouraged. Over the next two<br />

decades, he would score hundreds of radio shows, most broadcast<br />

live and many drawn from popular crime fiction.<br />

Dashiell Hammett inspired two of the best. 1939’s Campbell<br />

Playhouse adaptation of The Glass Key starred 24-year-old Orson<br />

Welles, the Playhouse’s producer/director, as charismatic, corrupt<br />

politician Paul Madvig—a performance enhanced by Herrmann’s<br />

original cues and bluesy source tunes. The program aired five months<br />

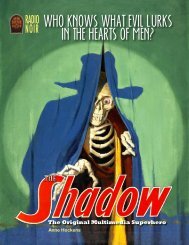

The composer’s onscreen credit in Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man<br />

www.filmnoirfoundation.org I FALL 2011 I NOIR CITY 29