Outdoor Resources Review Group Report - American Recreation ...

Outdoor Resources Review Group Report - American Recreation ...

Outdoor Resources Review Group Report - American Recreation ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

and recreation facilities in states and urban<br />

areas, perhaps understandably, have not been<br />

the Park Service’s top priority. Without explicit<br />

recognition in open space programs, such<br />

important issues as capital needs in urban parks<br />

or accessibility to close-to-home recreation, for<br />

example, may receive only marginal attention.<br />

Though plentiful at all levels of government,<br />

planning processes are not integrated in any<br />

meaningful fashion and thus have not been<br />

adequate to facilitate setting priorities and<br />

ensuring effective and efficient expenditure<br />

of funds. Despite numerous planning<br />

requirements associated with public programs<br />

for parks, wildlife, forestry, air and water quality,<br />

and more, an overall picture of conditions and<br />

trends in land and water conservation remains<br />

elusive. Identifying and targeting resources<br />

worthy of protection is near impossible.<br />

Crafting strategies to address these priorities is<br />

difficult. The quality of plans differs markedly<br />

from state to state. And they fail to capture<br />

the full range of outdoor resources or tie in<br />

the work of public and private organizations<br />

engaged in land and water conservation.<br />

The problem is not that planning tools are not<br />

available but rather the lack of incentive to<br />

use them and the lack of resources to prepare<br />

them. The State Comprehensive <strong>Outdoor</strong><br />

<strong>Recreation</strong> Plan, required for eligibility to<br />

receive LWCF monies, is supposed to assess<br />

needs and priorities. Some states take the<br />

obligation seriously and update their plans<br />

regularly to reflect changing demographics,<br />

new preferences for recreation and outdoor<br />

activities, or other strategic considerations.<br />

Others, seeing scant motivation for planning<br />

without assurance that stateside LWCF funding<br />

will be available, appear to put little effort into<br />

updating their plans. Plans for their own sake<br />

are clearly not worth the trouble. And typically<br />

26 GREAT OUTDOORS AMERICA<br />

the plans are incomplete in capturing the<br />

full range of state and local recreation lands<br />

and waters.<br />

Another example is the State Wildlife Action<br />

Plan, which is required to tap a grant program<br />

administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife<br />

Service. These state plans identify species at<br />

risk and needed conservation actions. These,<br />

too, differ in quality from state to state. No one<br />

document in many states captures all outdoor<br />

resources. New York’s wildlife action plan, for<br />

example, does not factor in 400,000 acres of<br />

state parklands. That state’s Open Space plan<br />

may come closest to the objective: it is revised<br />

every three years through statewide hearings<br />

that document urban, suburban, and rural<br />

places where important values—watersheds or<br />

wildlife corridors, for instance—merit protection.<br />

Consequently, although significant amounts<br />

of money are spent on planning required by<br />

government programs, the payoff in protecting<br />

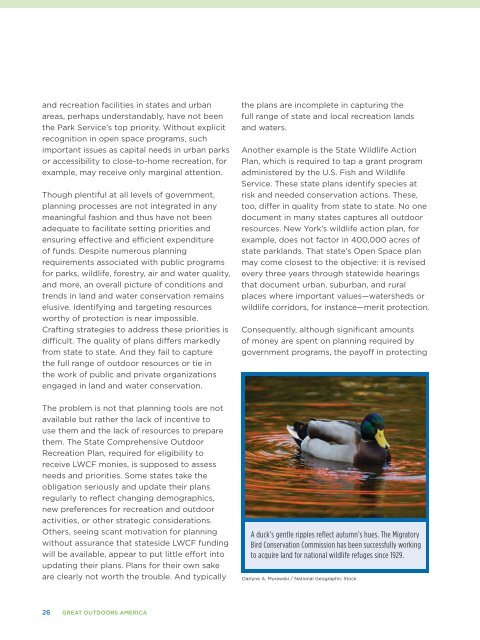

A duck’s gentle ripples reflect autumn’s hues. The Migratory<br />

Bird Conservation Commission has been successfully working<br />

to acquire land for national wildlife refuges since 1929.<br />

Darlyne A. Murawski / National Geographic Stock