American Magazine, Nov. 2013

The flagship publication of American University. This magazine offers a lively look at what AU was and is, and where it's going. It's a forum where alumni and friends can connect and engage with the university.

The flagship publication of American University. This magazine offers a lively look at what AU was and is, and where it's going. It's a forum where alumni and friends can connect and engage with the university.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

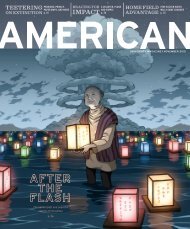

“It’s highly<br />

emotional.<br />

Many times<br />

people cry at<br />

naturalization<br />

procedures.<br />

Are they crying<br />

because they’re<br />

so happy to be<br />

<strong>American</strong>s? For<br />

many I think<br />

that’s true. Are<br />

they crying<br />

because they’re<br />

leaving something<br />

behind and cutting<br />

themselves off<br />

from a dimension<br />

of their former<br />

life? It is a very<br />

important moment<br />

of transition.”<br />

—Alan Kraut,<br />

professor of history<br />

“I’m always<br />

going to be an<br />

Afghan, but<br />

I’m also an<br />

<strong>American</strong> now.”<br />

Eleven-year-old Mohammadulla Hassan’s<br />

days were spent in the manner of men.<br />

Inside the cramped two-room apartment<br />

he shared with his parents, five of his seven<br />

siblings, and another family in Islamabad,<br />

Pakistan, he’d be jostled awake by 7 a.m.,<br />

then head to work. At the local bizarre he<br />

sold plastic bags for two rupees each (turning<br />

a one rupee profit) to shoppers buying fruits<br />

and vegetables. As day turned to dusk, he’d<br />

scour the city collecting scraps of cardboard,<br />

which he then flipped to recyclers for three<br />

rupees per pound. Often, he didn’t return<br />

home until 9 at night.<br />

He had never been enrolled in a school,<br />

knew no English, and although he could<br />

speak Farsi, could not read or write it.<br />

The Hassans are Afghans and Shiite<br />

Muslims, refugees who were driven from<br />

their homeland in the late ’90s by the Taliban.<br />

Across the border, life was safer but no easier.<br />

“We didn’t have any future,” Hassan, now<br />

19, says. “Education was always important<br />

to my parents. We weren’t able to get that in<br />

Pakistan. My parents knew that if we moved<br />

back to Afghanistan, it would be the same<br />

thing. To come to the United States, there<br />

would be opportunities for a better life.”<br />

Dullah, as his friends call him, is<br />

recounting this on a bench in front of the<br />

Mary Graydon Center on a sunny early<br />

September day. Behind him on the quad,<br />

students lounge on blankets, soaking up sun<br />

and laughing with their friends. Frisbees,<br />

not bullets, fly through the air. That he could<br />

blend into this idyllic setting—a few weeks<br />

earlier he arrived at AU to begin his freshman<br />

year—is a proposition he or any other rational<br />

person would have found unthinkable just<br />

eight years ago.<br />

Only in America, as the cliché goes. For<br />

millions of immigrants who make their way<br />

to this country in pursuit of the same thing<br />

the Hassans were chasing—“a better life”—the<br />

phrase has deep meaning.<br />

Hassan has a full plate these days. He’s<br />

adjusting to the nuances of dorm cohabitation,<br />

diving into financial accounting class (he wants<br />

to become an economist), and trying to find time<br />

to play soccer. But these activities, all important<br />

ones to an undergrad, have taken a back seat to<br />

another: pursuing <strong>American</strong> citizenship.<br />

Pushed by their hearts, their heads, or<br />

their wallets, hundreds of thousands of<br />

people each year become U.S. citizens. Their<br />

motivations range from patriotic to pragmatic.<br />

Like the country they’re becoming a part<br />

of, new <strong>American</strong>s are a complex, diverse<br />

group with a wide spectrum of pasts, present<br />

circumstances, and futures.<br />

Naturalization is not a quick process.<br />

Applicants must be permanent residents for<br />

at least five years; undergo a background<br />

check; prove they can speak, read, and write<br />

English; and pass a civics test before they earn<br />

the right to raise their right hand and take the<br />

oath of allegiance.<br />

“I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely<br />

and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance<br />

and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate,<br />

state or sovereignty, of whom or which I have<br />

heretofore been a subject or citizen; that I will<br />

support and defend the Constitution and laws<br />

of the United States of America against all<br />

enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear<br />

true faith and allegiance to the same; that I<br />

will bear arms on behalf of the United States<br />

when required by the law; that I will perform<br />

noncombatant service in the armed forces of the<br />

United States when required by the law; that I<br />

will perform work of national importance under<br />

civilian direction when required by the law; and<br />

that I take this obligation freely without any<br />

28 <strong>American</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> NOVEMBER <strong>2013</strong>