Effect of Glass Composition on Activation Energy of Viscocity in ...

Effect of Glass Composition on Activation Energy of Viscocity in ...

Effect of Glass Composition on Activation Energy of Viscocity in ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

This article appeared <strong>in</strong> a journal published by Elsevier. The attached<br />

copy is furnished to the author for <strong>in</strong>ternal n<strong>on</strong>-commercial research<br />

and educati<strong>on</strong> use, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>in</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> at the authors <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong><br />

and shar<strong>in</strong>g with colleagues.<br />

Other uses, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g reproducti<strong>on</strong> and distributi<strong>on</strong>, or sell<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

licens<strong>in</strong>g copies, or post<strong>in</strong>g to pers<strong>on</strong>al, <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al or third party<br />

websites are prohibited.<br />

In most cases authors are permitted to post their versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

article (e.g. <strong>in</strong> Word or Tex form) to their pers<strong>on</strong>al website or<br />

<strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al repository. Authors requir<strong>in</strong>g further <strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong><br />

regard<strong>in</strong>g Elsevier’s archiv<strong>in</strong>g and manuscript policies are<br />

encouraged to visit:<br />

http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

Author's pers<strong>on</strong>al copy<br />

Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N<strong>on</strong>-Crystall<strong>in</strong>e Solids 358 (2012) 1818–1829<br />

C<strong>on</strong>tents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect<br />

Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N<strong>on</strong>-Crystall<strong>in</strong>e Solids<br />

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/ locate/ jn<strong>on</strong>crysol<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Effect</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> glass compositi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> activati<strong>on</strong> energy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> viscosity <strong>in</strong><br />

glass-melt<strong>in</strong>g-temperature range<br />

Pavel Hrma a,b, ⁎, Sang-Soo Han a<br />

a Divisi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Advanced Nuclear Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g, Pohang University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Science and Technology, Pohang, Republic <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Korea<br />

b Pacific Northwest Nati<strong>on</strong>al Laboratory, Richland, WA 99352, USA<br />

article<br />

<strong>in</strong>fo<br />

abstract<br />

Article history:<br />

Received 7 February 2012<br />

Received <strong>in</strong> revised form 14 May 2012<br />

Available <strong>on</strong>l<strong>in</strong>e 10 June 2012<br />

Keywords:<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Glass</str<strong>on</strong>g> viscosity;<br />

Nuclear waste glass;<br />

Viscosity–compositi<strong>on</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ship;<br />

Activati<strong>on</strong> energy;<br />

Mixture models<br />

In the high-temperature range, where the viscosity (η) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> molten glass is b10 3 Pa s, the activati<strong>on</strong> energy (B)is<br />

virtually <strong>in</strong>dependent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> temperature (T). Moreover, the coefficient A <strong>in</strong> the Arrhenius relati<strong>on</strong>ship, ln(η)=A+<br />

B/T, is nearly <strong>in</strong>dependent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> melt compositi<strong>on</strong>. Hence, the viscosity–compositi<strong>on</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ship for ηb10 3 Pa s is<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ed by B as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong>. Us<strong>in</strong>g a database encompass<strong>in</strong>g over 1300 compositi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> high-level<br />

waste glasses with nearly 7000 viscosity data, we developed mathematical models for B(x), where x is the compositi<strong>on</strong><br />

vector <strong>in</strong> terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ents. In this paper, we present 13 versi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> B(x) asfirstand<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>d-order polynomials with coefficients for 15 to 39 comp<strong>on</strong>ents, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Others, a comp<strong>on</strong>ent that<br />

sums c<strong>on</strong>stituents hav<strong>in</strong>g little effect <strong>on</strong> viscosity.<br />

© 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.<br />

1. Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Under normal c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, glass viscosity (η) is a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> temperature<br />

(T) and compositi<strong>on</strong>, i.e., η=η(T,x), where x is the compositi<strong>on</strong><br />

vector (array <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mass or mole fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> glass comp<strong>on</strong>ents). Historically,<br />

viscosity–compositi<strong>on</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ships were mostly restricted to<br />

tables and diagrams [1–3], although various formulas were proposed<br />

for limited compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>s. Only when large databases, such as<br />

Sci<str<strong>on</strong>g>Glass</str<strong>on</strong>g> [3], became available <strong>in</strong> electr<strong>on</strong>ic form, did serious attempts<br />

beg<strong>in</strong> to reduce large amounts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data to coefficients <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> polynomial<br />

functi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mass or mole fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ents [4]. Suchfuncti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

are <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten c<strong>on</strong>structed <strong>in</strong> terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> isokoms, i.e., T=f η (x), that relate the<br />

temperature to compositi<strong>on</strong> with η as a parameter. The isokom representati<strong>on</strong><br />

leaves to the user the choice <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the form <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> η = f x (T), i.e., the<br />

viscosity–temperature functi<strong>on</strong> for a given compositi<strong>on</strong>, from am<strong>on</strong>g<br />

dozens <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> relati<strong>on</strong>ships; am<strong>on</strong>g these, the Vogel–Fulcher–Tammann<br />

equati<strong>on</strong> and the Adams-Gibbs equati<strong>on</strong> are the most popular (some<br />

authors fit both these equati<strong>on</strong>s to their data [5]). However, the freedom<br />

to select an appropriate η=f x (T) functi<strong>on</strong> from the smorgasbord<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> available choices is limited by the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> parameters <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the T=<br />

f η (x) relati<strong>on</strong>, which is usually small—typically just three. On the other<br />

hand, the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> η(T) data for glasses is usually large enough to<br />

enable a satisfactory choice <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a representative approximati<strong>on</strong> functi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Alternatively, viscosity can be expressed as η=f T (x), where T is<br />

the parameter. Therefore, it is advantageous to preselect an analytical<br />

⁎ Corresp<strong>on</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g author at: Pacific Northwest Nati<strong>on</strong>al Laboratory, Richland, WA<br />

99352, USA.<br />

E-mail address: pavelhrma@postech.ac.kr (P. Hrma).<br />

form <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> η=f x (T) and then express its coefficients as functi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong><br />

[6–8].<br />

The task <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> select<strong>in</strong>g an adequate η=f x (T) functi<strong>on</strong> for a family <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

glasses, such as borosilicate commercial glasses or nuclear waste glasses,<br />

can be facilitated by the follow<strong>in</strong>g assumpti<strong>on</strong>s [8] that rule out many,<br />

if not most, η=f x (T) relati<strong>on</strong>ships proposed <strong>in</strong> the literature:<br />

1. The viscosity at the glass transiti<strong>on</strong> temperature, T g , is <strong>in</strong>dependent<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

2. As T <strong>in</strong>creases, the η=f x (T) functi<strong>on</strong> asymptotically approaches<br />

the Arrhenius functi<strong>on</strong>, ln(η)=A+B/T, with the coefficient A <strong>in</strong>dependent<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

3. The η=f x (T) functi<strong>on</strong> approaches the Arrhenius functi<strong>on</strong> fast enough<br />

to become virtually <strong>in</strong>dist<strong>in</strong>guishable from it (with<strong>in</strong> experimental<br />

error) when the viscosity is below 10 2 to 10 3 Pa s, depend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>on</strong><br />

the glass family and measurement accuracy.<br />

4. The number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> temperature-<strong>in</strong>dependent coefficients should be as<br />

low as possible.<br />

Note: Some authors postulate that η→∞ <strong>on</strong>ly when T→0 [9,10].<br />

However, this c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> has no practical implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>in</strong> glass technology<br />

and its theoretical justificati<strong>on</strong> is arguable. It can be met either<br />

with more empirical coefficients [9] or by violat<strong>in</strong>g some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the c<strong>on</strong>stitutive<br />

assumpti<strong>on</strong>s stated above.<br />

By assumpti<strong>on</strong>s 2 and 3, high-temperature viscosity data (i.e., ηb<br />

10 3 Pa s), both for commercial and waste glasses, are satisfactorily fitted<br />

by the Arrhenius functi<strong>on</strong> [6,7,11] with a temperature-<strong>in</strong>dependent<br />

activati<strong>on</strong> energy (B),<br />

lnðηÞ ¼ A þ BðxÞ=T<br />

ð1Þ<br />

0022-3093/$ – see fr<strong>on</strong>t matter © 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.<br />

doi:10.1016/j.jn<strong>on</strong>crysol.2012.05.030

Author's pers<strong>on</strong>al copy<br />

P. Hrma, S-S. Han / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N<strong>on</strong>-Crystall<strong>in</strong>e Solids 358 (2012) 1818–1829<br />

1819<br />

where A is a c<strong>on</strong>stant coefficient. This equati<strong>on</strong> has a great advantage<br />

<strong>in</strong> its simplicity, hav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>on</strong>ly two coefficients, A and B, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which <strong>on</strong>ly B<br />

depends <strong>on</strong> glass compositi<strong>on</strong>. Because viscosity is usually around<br />

10 Pa s at glass-process<strong>in</strong>g temperatures, it is suitable for formulat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

glasses that meet melt-process<strong>in</strong>g c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>ts.<br />

The activati<strong>on</strong> energy is usually expressed as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong><br />

us<strong>in</strong>g the c<strong>on</strong>cept <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> partial properties [11,12]. Thus,<br />

B ¼ XN<br />

i¼1<br />

B i x i<br />

where x i is the ith comp<strong>on</strong>ent's mass fracti<strong>on</strong>, B i is the ith comp<strong>on</strong>ent's<br />

partial specific activati<strong>on</strong> energy, and N is the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ents.<br />

Partial properties are themselves functi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong>, but B i s<br />

can be approximated as c<strong>on</strong>stants for narrow ranges <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

For highly <strong>in</strong>teractive comp<strong>on</strong>ents, especially those with a wide range<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s, B i s can be approximated as l<strong>in</strong>ear functi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Thus,<br />

B i ¼ XN<br />

j¼1<br />

B ij x j<br />

where B ij is the ith and jth comp<strong>on</strong>ents' sec<strong>on</strong>d-order coefficient.<br />

Comb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Eqs. (2) and (3) and rearrang<strong>in</strong>g, we obta<strong>in</strong><br />

B ¼ XN<br />

i¼j<br />

X N<br />

j¼1<br />

B ij x i x j<br />

where B ii ¼ B ii and B ij ¼ B ij þ B ji (the B ij matrix is not necessarily<br />

symmetrical). Hence, the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> terms <strong>in</strong> Eq. (4) is N 2 =(1/2)<br />

N(N+1), corresp<strong>on</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g to N 2 sec<strong>on</strong>d-order coefficients.<br />

Compared to commercial glasses, high-level waste (HLW) glasses<br />

have a large number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ents with c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s not encountered<br />

<strong>in</strong> commercial <strong>in</strong>dustry or <strong>in</strong> geology. Develop<strong>in</strong>g mathematical<br />

models that relate viscosity to compositi<strong>on</strong> for these glasses is not<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly important for waste glass formulati<strong>on</strong>, but also <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

researchers who endeavor to relate empirical coefficients to the melt<br />

structure.<br />

Obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g sec<strong>on</strong>d-order coefficients for a large number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ents<br />

requires a large number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data. If each coefficient should be<br />

supported by at least 4 <strong>in</strong>dependent data po<strong>in</strong>ts, 220 data po<strong>in</strong>ts are<br />

needed for a mixture with just 10 comp<strong>on</strong>ents. Fortunately, a huge<br />

viscosity database has been accumulated for HLW glasses at various<br />

laboratories <strong>in</strong> the U.S. over the past decades. The database compiled<br />

at Pacific Northwest Nati<strong>on</strong>al Laboratory [13] comprises over 1300<br />

compositi<strong>on</strong>s with 83 comp<strong>on</strong>ents and nearly 7000 data for viscosities<br />

b10 3 Pa s. The l<strong>in</strong>ear <strong>in</strong>dependence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the glass comp<strong>on</strong>ents was dem<strong>on</strong>strated<br />

by the scatter-plot matrix as well as the correlati<strong>on</strong> matrix<br />

[13]. Us<strong>in</strong>g this database and Eqs. (1) to (4), we have developed several<br />

versi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> viscosity–compositi<strong>on</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ships with various soluti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

for first- and sec<strong>on</strong>d-order coefficients.<br />

Unlike viscosity–compositi<strong>on</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ships based <strong>on</strong> limited numbers<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> glass compositi<strong>on</strong>s specifically tailored for the model development<br />

[7,11], or <strong>on</strong> a broad compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong> available from the<br />

literature [4], we used a large amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data collected from various<br />

sources, but c<strong>on</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ed to nuclear waste glasses [13]. The model previously<br />

developed from this database preferred the Vogel–Fulcher–<br />

Tammann equati<strong>on</strong> fitted to 967 data po<strong>in</strong>ts us<strong>in</strong>g 72 parameters<br />

and 23 comp<strong>on</strong>ents (R 2 =0.96). Because viscosity data <strong>in</strong> this database<br />

are with<strong>in</strong> the Arrhenius range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the η=f x (T) relati<strong>on</strong>ships,<br />

assumpti<strong>on</strong>s 2 and 3 stated above allowed us to develop models<br />

based <strong>on</strong> Eq. (4) and represent<strong>in</strong>g 5900 to 6200 data with 25–60<br />

parameters and up to 39 comp<strong>on</strong>ents (R 2 =0.98). Model fitt<strong>in</strong>g was<br />

d<strong>on</strong>e with the solver <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Excel. We have explored the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> model<br />

design <strong>on</strong> the model applicability to glass formulati<strong>on</strong> and <strong>on</strong> the<br />

ð2Þ<br />

ð3Þ<br />

ð4Þ<br />

resp<strong>on</strong>se <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> melt viscosity to compositi<strong>on</strong> variability. Thus, apart<br />

from provid<strong>in</strong>g collecti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ready-made coefficients for viscosity<br />

estimates, our work may open a discussi<strong>on</strong> about the c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the viscosity–compositi<strong>on</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ships.<br />

2. Data preparati<strong>on</strong><br />

The Pacific Northwest Nati<strong>on</strong>al Laboratory (PNNL) database [13]<br />

reports both targeted and analytical compositi<strong>on</strong>s. Because analytical<br />

data were not obta<strong>in</strong>ed for a substantial number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> glasses, we chose<br />

the targeted compositi<strong>on</strong>s for model development. Before fitt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

model equati<strong>on</strong>s to data, we have simplified the database us<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

redox state c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>, restrict<strong>in</strong>g the compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>, and def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

and impos<strong>in</strong>g a data acceptability limit. These data arrangements<br />

are described below.<br />

2.1. Redox state c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong><br />

Out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 83 comp<strong>on</strong>ents identified <strong>in</strong> the database, oxides <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> various<br />

elements (As, Ce, Co, Fe, Mn, Mo, Pb, Pr, Re, Rh, Sb, Sn, Tc, Tl, and U)<br />

are listed <strong>in</strong> more than <strong>on</strong>e valence state <strong>in</strong> the database [13]. These<br />

valence states do not necessarily corresp<strong>on</strong>d to their actual presence<br />

<strong>in</strong> molten glass at the temperature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> viscosity measurement. Therefore,<br />

we followed an established c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> choos<strong>in</strong>g a s<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

valency for each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these oxides: As 2 O 3 ,Ce 2 O 3 , CoO, Fe 2 O 3 , MnO,<br />

MoO 3 , PbO, Pr 2 O 3 ,Re 2 O 7 ,Rh 2 O 3 ,Sb 2 O 3 , SnO, Tc 2 O 7 ,Tl 2 O, and UO 2 .<br />

Even though oxides <strong>in</strong> different oxidati<strong>on</strong> states affect viscosity differently,<br />

their proporti<strong>on</strong>s are neither arbitrary nor fully determ<strong>in</strong>ed by<br />

the batch materials if we assume that the glasses were reas<strong>on</strong>ably<br />

close to equilibrium with air or oxygen bubbles at some specific temperature.<br />

Thus, provided that the partial pressure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oxygen was similar<br />

<strong>in</strong> glasses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different compositi<strong>on</strong>s, each B i coefficient obta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

for a s<strong>in</strong>gle oxide effectively represents the true redox state <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

element.<br />

To make up for the changes <strong>in</strong> oxygen c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> caused by<br />

applicati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the redox state c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>, we renormalized glass<br />

compositi<strong>on</strong> to comp<strong>on</strong>ent mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s that sum to 1, i.e.,<br />

X N<br />

i¼1<br />

x i ¼ 1<br />

On apply<strong>in</strong>g the s<strong>in</strong>gle redox state c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>, the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

comp<strong>on</strong>ents decreased to 56.<br />

2.2. M<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents and SO 3<br />

After sort<strong>in</strong>g data by viscosity, we have removed from the database<br />

data with η>1050 Pa s. This reduced the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data po<strong>in</strong>ts<br />

from 6884 to 6765. Then, us<strong>in</strong>g Eq. (1), we calculated the activati<strong>on</strong><br />

energy for each data po<strong>in</strong>t, i.e., each (η, T) couple, as<br />

B ¼ Tðln η−AÞ ð6Þ<br />

where we <strong>in</strong>itially used an estimated value <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> A=−11.35, but then<br />

kept A as a fitt<strong>in</strong>g parameter to be eventually determ<strong>in</strong>ed by leastsquares<br />

optimizati<strong>on</strong>. Thus, when fitt<strong>in</strong>g Eq. (2) to B(x) data, we<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed values <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> both A and the first-order coefficients, B i s. For<br />

this prelim<strong>in</strong>ary fit, the coefficient <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> determ<strong>in</strong>ati<strong>on</strong> was R 2 =0.9172.<br />

The fit assigned unrealistically high B i values for SO 3 and some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the 17 m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents for which the mass fracti<strong>on</strong> did not exceed<br />

1 mass% <strong>in</strong> any glass (Cs 2 O, Sb 2 O 3 , SeO 2 ,Tl 2 O, Tc 2 O 7 ,Ag 2 O, RuO 2 ,<br />

Pr 2 O 3 , WO 3 , As 2 O 3 , I, PdO, Re 2 O 7 , Rh 2 O 3 , Rb 2 O, Br, and Nb 2 O 5 ).<br />

Because comp<strong>on</strong>ents with x i b0.01 generally have little impact <strong>on</strong><br />

viscosity, we removed the mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these 17 comp<strong>on</strong>ents<br />

from the list <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> viscosity-affect<strong>in</strong>g variables.<br />

ð5Þ

Author's pers<strong>on</strong>al copy<br />

1820 P. Hrma, S-S. Han / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N<strong>on</strong>-Crystall<strong>in</strong>e Solids 358 (2012) 1818–1829<br />

To meet the mass-fracti<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>t, Eq. (5), for the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

39 viscosity-affect<strong>in</strong>g comp<strong>on</strong>ents, we exam<strong>in</strong>ed two opti<strong>on</strong>s: either<br />

delet<strong>in</strong>g the comp<strong>on</strong>ents with x i b0.01 and renormaliz<strong>in</strong>g the mass<br />

fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g comp<strong>on</strong>ents, or summ<strong>in</strong>g the x i s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

removed comp<strong>on</strong>ents <strong>in</strong>to a s<strong>in</strong>gle comp<strong>on</strong>ent called “Others.” As<br />

expected, the coefficient <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> determ<strong>in</strong>ati<strong>on</strong> was marg<strong>in</strong>ally lower with<br />

the first opti<strong>on</strong> (R 2 =0.9172) than with the sec<strong>on</strong>d (R 2 =0.9176). However,<br />

the ma<strong>in</strong> reas<strong>on</strong> for choos<strong>in</strong>g the sec<strong>on</strong>d opti<strong>on</strong> for subsequent<br />

calculati<strong>on</strong>s was that hav<strong>in</strong>g the Others comp<strong>on</strong>ent appeared advantageous<br />

for the subsequent model development (see Secti<strong>on</strong> 6).<br />

Another comp<strong>on</strong>ent with an unrealistically high B i , though with<br />

x i >0.01 <strong>in</strong> several targeted compositi<strong>on</strong>s, was SO 3 . The B SO3 value<br />

appeared to be the highest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all coefficients and rema<strong>in</strong>ed extremely<br />

high (B SO3 =3.65×10 4 K) even after two glasses with >2.0 mass%<br />

SO 3 were deleted from the database. This impossible value was most<br />

likely caused by SO 3 segregati<strong>on</strong> and evaporati<strong>on</strong> from the melts as<br />

a result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which the targeted c<strong>on</strong>tent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> SO 3 was not reta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the<br />

glass. The actual SO 3 c<strong>on</strong>tent would thus likely classify SO 3 as a<br />

m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ent. Replac<strong>in</strong>g targeted SO 3 fracti<strong>on</strong>s with analytical<br />

<strong>on</strong>es did not appear practicable. After some deliberati<strong>on</strong>s, we chose<br />

to add the SO 3 targeted fracti<strong>on</strong>s to Others while delet<strong>in</strong>g glasses<br />

with x SO3 >0.02. As a result, the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data decreased to 6755.<br />

2.3. Acceptability limit<br />

The R 2 =0.917 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the prelim<strong>in</strong>ary first-order model was rather<br />

low, c<strong>on</strong>sider<strong>in</strong>g the size <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the database. Sort<strong>in</strong>g the data accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to the value <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Δ 2 =(B M −B C ) 2 , where the subscripts M and C denote<br />

measured and calculated values, respectively, identified data with<br />

extremely large deviati<strong>on</strong>s between model and measurement. If<br />

such outliers were accepted for model generati<strong>on</strong>, they would unduly<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence the outcome and <strong>in</strong>crease the model uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty for the<br />

majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data.<br />

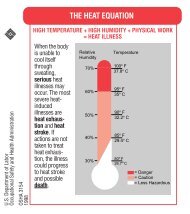

To def<strong>in</strong>e outliers, we established an acceptability limit. Fig. 1 displays<br />

the plot <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Δ 2 versus n, where n is the cumulative number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

data sorted by Δ 2 from smallest to largest. To obta<strong>in</strong> Δ 2 , we calculated<br />

B M us<strong>in</strong>g Eq. (6) and B C us<strong>in</strong>g Eq. (2) <strong>in</strong> which B i s and A came from a<br />

prelim<strong>in</strong>ary first-order model. The Δ 2 values varied by 11 orders <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

magnitude, from 5.4×10 −4 K 2 to 2.3×10 7 K 2 , i.e., from extremely<br />

low values for data for which B C s happened, more or less accidentally,<br />

to be nearly identical to B M s, to very large <strong>on</strong>es for err<strong>on</strong>eous data<br />

not captured by the model. As Fig. 1 shows, the logarithms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Δ 2<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased nearly l<strong>in</strong>early with n for n between 3000 and 6000 (Δ 2<br />

between 3.2×10 4 and 1.3×10 5 K 2 ). The obvious candidates for outliers<br />

were data with Δ 2 >3.3×10 5 K 2 . Therefore, we selected Δ 2 =<br />

3.3×10 5 K 2 as the limit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> acceptability (the horiz<strong>on</strong>tal l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> Fig. 1)<br />

and used this limit for all but two models.<br />

log[(Δ/K) 2 ]<br />

8<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

Δ 2 = 3.3x10 5 K 2<br />

4<br />

2 3 4 5 6 7<br />

10 -3 n<br />

Fig. 1. Deviati<strong>on</strong> squared, Δ 2 =(B M − B C ) 2 , versus n, the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data sorted by Δ 2 .<br />

Table 1<br />

Model A comp<strong>on</strong>ent coefficients and the maximum (x im ) and average (x ia ) comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

10 − 4 B i (K) x im x ia 10 − 4 B i (K) x im x ia<br />

SiO 2 3.001 0.6413 0.4606 Gd 2 O 3 1.485 0.0772 0.0028<br />

Na 2 O −0.031 0.3505 0.1294 Ce 2 O 3 1.824 0.0712 0.0039<br />

Fe 2 O 3 1.565 0.2639 0.0527 F −0.437 0.0600 0.0035<br />

Al 2 O 3 3.506 0.2663 0.0734 V 2 O 5 1.417 0.0599 0.0009<br />

SrO 0.969 0.2990 0.0057 La 2 O 3 0.681 0.0500 0.0023<br />

K 2 O 0.877 0.1000 0.0142 BaO 0.601 0.0471 0.0018<br />

B 2 O 3 0.352 0.2019 0.0837 Eu 2 O 3 1.526 0.0436 0.0001<br />

CaO 0.558 0.1500 0.0303 Sm 2 O 3 1.607 0.0436 0.0001<br />

Bi 2 O 3 1.361 0.1618 0.0015 CdO 0.983 0.0400 0.0018<br />

ZrO 2 2.712 0.1581 0.0322 SnO 2.034 0.0346 0.0002<br />

UO 2 2.096 0.1462 0.0033 NiO 0.397 0.0212 0.0033<br />

MnO 0.544 0.1360 0.0053 HfO 2 2.093 0.0311 0.0000<br />

P 2 O 5 2.631 0.1311 0.0085 Ga 2 O 3 2.061 0.0302 0.0001<br />

TiO 2 1.318 0.0535 0.0036 Y 2 O 3 1.636 0.0302 0.0001<br />

ZnO 1.179 0.0986 0.0095 CuO 1.288 0.0299 0.0004<br />

PbO 1.036 0.0967 0.0014 Cr 2 O 3 1.003 0.0297 0.0016<br />

MgO 1.184 0.0821 0.0094 CoO 2.005 0.0223 0.0001<br />

Li 2 O −3.937 0.0899 0.0303 MoO 3 1.902 0.0201 0.0013<br />

Nd 2 O 3 2.083 0.0838 0.0050 Others 1.627 0.1075 0.0131<br />

ThO 2 1.568 0.0781 0.0028<br />

For each model, we started computati<strong>on</strong> with the full set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data<br />

(orig<strong>in</strong>al or reduced, see Secti<strong>on</strong> 3.2). After the first fitt<strong>in</strong>g, we repeatedly<br />

removed data exceed<strong>in</strong>g the acceptability limit and refitted the<br />

model until the selecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> acceptable data stabilized. Model A is a<br />

first-order model thus fitted to obta<strong>in</strong> B i coefficients for 39 comp<strong>on</strong>ents<br />

listed <strong>in</strong> Table 1. AsTable 2 shows, the compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

orig<strong>in</strong>al data and acceptable data are nearly identical. Maximum<br />

mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s decreased for <strong>on</strong>ly 6 comp<strong>on</strong>ents (SiO 2 ,Fe 2 O 3 ,K 2 O,<br />

CaO, MgO, and NiO), and m<strong>in</strong>imum mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s (0 for all comp<strong>on</strong>ents<br />

but SiO 2 and Na 2 O) <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>on</strong>ly for SiO 2 (from 0.194 to<br />

0.214).<br />

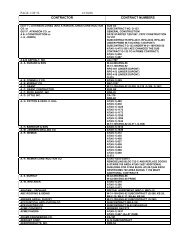

Fig. 2 displays all data po<strong>in</strong>ts with ηb1050 Pa s <strong>on</strong> the (T − 1 , log η)<br />

and (T − 1 , B) planes. The T spans the <strong>in</strong>terval from 752 to 1806 °C and<br />

log(η/Pa s) from −0.85 to 3.02. The T span <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Model A acceptable data<br />

shrank to the <strong>in</strong>terval from 800 to 1632 °C and the span <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> log(η/Pa s)<br />

ranged from −0.51 to 2.57. Fig. 2 compares acceptable data with all<br />

data, and <strong>in</strong>dicates that most <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 856 outliers lie <strong>in</strong>side the (T −1 , B)<br />

regi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> accepted data.<br />

2.4. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Compositi<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> regi<strong>on</strong> and fitt<strong>in</strong>g parameters<br />

Model A encompasses all 39 comp<strong>on</strong>ents. Other models use 15 to<br />

24 viscosity-affect<strong>in</strong>g comp<strong>on</strong>ents. Comp<strong>on</strong>ents that are less likely to<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence viscosity for most glasses were identified by sort<strong>in</strong>g comp<strong>on</strong>ents<br />

accord<strong>in</strong>g to three criteria, i.e., B i −B a ,(B i −B a )x ia and (B i −B a )<br />

x iM , where subscripts a and M stand for average and maximum, respectively.<br />

Comp<strong>on</strong>ents Ce 2 O 3 , CoO, Cr 2 O 3 , CuO, Eu 2 O 3 ,Ga 2 O 3 , HfO 2 ,<br />

MoO 3 ,Nd 2 O 3 ,Sm 2 O 3 , SnO, ThO 2 , TiO 2 ,UO 2 ,Y 2 O 3 had low values <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

all the three criteria. After mov<strong>in</strong>g these comp<strong>on</strong>ents to Others, the<br />

compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong> shrank to N=24 comp<strong>on</strong>ents, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Others.<br />

Table 2<br />

Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> maximum comp<strong>on</strong>ent mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s for all data with η>1050 Pa⋅s and<br />

data with Δ 2 b3.3×10 5 K 2 .<br />

Comp<strong>on</strong>ent All data Selected data<br />

SiO 2 0.716 0.641<br />

Fe 2 O 3 0.345 0.264<br />

K 2 O 0.210 0.100<br />

CaO 0.182 0.150<br />

MgO 0.096 0.082<br />

NiO 0.030 0.021

Author's pers<strong>on</strong>al copy<br />

P. Hrma, S-S. Han / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N<strong>on</strong>-Crystall<strong>in</strong>e Solids 358 (2012) 1818–1829<br />

1821<br />

log( η/Pa.s)<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

All data<br />

Accepted data<br />

10 -4 B(K)<br />

3.0<br />

2.5<br />

2.0<br />

All data<br />

Accepted data<br />

0<br />

1.5<br />

- 1<br />

4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

10 4 / T(K)<br />

1.0<br />

4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

10 4 / T(K)<br />

Fig. 2. Positi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all data po<strong>in</strong>ts with ηb1050 Pa⋅s and data po<strong>in</strong>ts with Δ 2 b3.3×10 5 K 2 (selected data, Model A) <strong>on</strong> the (T 1 , log η) surface (left) and (T 1 , B) surface (right).<br />

Model B is a first-order model fitted to the 24 comp<strong>on</strong>ents. The<br />

standard procedure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> repeated fitt<strong>in</strong>g and Δ 2 -sort<strong>in</strong>g until the number<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> outliers stabilized resulted <strong>in</strong> 5893 acceptable data po<strong>in</strong>ts, <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

marg<strong>in</strong>ally less than the number for Model A (5909). Both the T<br />

span and log(η/Pa s) <strong>in</strong>terval rema<strong>in</strong>ed unaffected and the compositi<strong>on</strong><br />

regi<strong>on</strong> was unchanged except for the maximum mass fracti<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> SiO 2 , which decreased to 0.628. The comp<strong>on</strong>ent coefficients are<br />

listed <strong>in</strong> Table 3.<br />

The compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong> is a doma<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the (N-1)-dimensi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

compositi<strong>on</strong> space (by Eq. (5), <strong>on</strong>ly N-1 compositi<strong>on</strong> variables are<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent). Here we c<strong>on</strong>sider the compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong> as an (N-1)-<br />

dimensi<strong>on</strong>al box def<strong>in</strong>ed by the ranges <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ents,<br />

i.e., the m<strong>in</strong>imum and maximum values <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> x i for each comp<strong>on</strong>ent,<br />

even though the measured data are not distributed with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

multidimensi<strong>on</strong>al box with a representative uniformity. By Eqs. (2)<br />

and (4), the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ents limits the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

coefficients, B i and B ij , <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the first- and sec<strong>on</strong>d-order polynomial<br />

terms. The number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>zero first- and sec<strong>on</strong>d-order comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

coefficients, plus 1 for A as an additi<strong>on</strong>al fitt<strong>in</strong>g parameter, c<strong>on</strong>stitutes<br />

the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> model parameters, p.<br />

3. Sec<strong>on</strong>d-order models<br />

3.1. First-order model augmented with sec<strong>on</strong>d-order terms<br />

For the computati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sec<strong>on</strong>d-order effects, we selected 8 major<br />

comp<strong>on</strong>ents with the highest values <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> (B i −B a )x ia (based <strong>on</strong> firstorder<br />

coefficients), namely, SiO 2 ,Na 2 O, Li 2 O, B 2 O 3 ,Al 2 O 3 , CaO, ZrO 2 ,<br />

and Fe 2 O 3 . Thus, the full sec<strong>on</strong>d-order B ij matrix has N 2 =36 coefficients.<br />

In the basel<strong>in</strong>e Model C, we added these sec<strong>on</strong>d-order terms<br />

to the first-order terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Model B. Thus, the activati<strong>on</strong> energy for<br />

viscosity <strong>in</strong> sec<strong>on</strong>d-order models was expressed by the formula<br />

B ¼ XN 1<br />

B i x i þ XN M<br />

i¼1<br />

i¼j<br />

X N M<br />

j¼1<br />

B ij x i x j<br />

ð7Þ<br />

Table 3<br />

Summary <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> first-order coefficients, B i ,<strong>in</strong>10 4 K. Also <strong>in</strong>cluded are the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data selected (n s ), the Arrhenius A coefficient, the coefficient <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> determ<strong>in</strong>ati<strong>on</strong> (R 2 ), the number<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> model parameters (p), the average activati<strong>on</strong> energy (B a ), and the activati<strong>on</strong> energy standard deviati<strong>on</strong> (S).<br />

Model A (a) B C D E F G H I J K L M<br />

n s 5909 5893 6239 5969 5950 5867 3589 1471 5839 5313 6129 5764 5910<br />

A −11.23 −11.19 −11.42 −11.44 −11.43 −11.37 −11.29 −11.24 −11.49 −11.06 −11.37 −11.39 −11.429<br />

R 2 0.9712 0.9710 0.9804 0.9811 0.9807 0.9795 0.9960 0.9995 0.9803 0.9728 0.9781 0.9784 0.9804<br />

p 40 25 61 61 55 52 52 52 53 31 45 44 38<br />

10 −4 B a (K) 1.8711 1.8660 1.8956 1.8981 1.8969 1.8890 1.8810 1.8697 1.9057 1.8469 1.7898 1.8923 1.8966<br />

10 − 4 S(K) 0.1460 0.1613 0.1523 0.1539 0.1539 0.1537 0.1500 0.1461 0.1534 0.1486 0.1527 0.1527 0.1535<br />

SiO 2 3.00 3.00 3.09 3.05 3.05 3.15 3.15 3.15 4.03<br />

Na 2 O −0.03 −0.04 −0.34 −0.26 −0.20 −0.22 −0.22 −0.22 1.05<br />

B 2 O 3 0.35 0.32 0.29 0.40 0.45 0.37 0.37 0.37 1.24<br />

Al 2 O 3 3.51 3.50 3.48 3.43 3.36 3.27 3.27 3.27 3.87<br />

Fe 2 O 3 1.57 1.55 0.81 0.78 0.80 0.53 0.53 0.53 1.62<br />

ZrO 2 2.71 2.71 1.86 1.77 1.68 1.54 1.54 1.54 2.00<br />

Li 2 O −3.94 −3.91 −4.52 −4.43 −4.37 −4.38 −4.38 −4.38 −3.88<br />

CaO 0.56 0.53 0.08 0.07 −0.01 0.17 0.17 0.17 0.92<br />

SrO 0.97 1.01 1.04 1.03 1.02 0.74 0.74 0.74 2.48 2.33 2.32 2.04 0.37<br />

K 2 O 0.88 0.80 0.99 1.02 1.00 1.03 1.03 1.03 2.54 2.49 2.53 2.51 0.26<br />

Bi 2 O 3 1.36 1.43 1.46 1.57 2.85 1.07<br />

MnO 0.54 0.46 0.77 0.77 0.79 2.17 1.75 2.15 0.07<br />

P 2 O 5 2.63 2.64 2.67 2.69 2.70 2.64 2.64 2.64 4.26 4.13 4.20 4.23 1.99<br />

ZnO 1.18 1.03 1.59 1.54 1.66 1.59 1.59 1.59 3.10 3.65 3.26 3.24 0.78<br />

PbO 1.04 0.98 1.29 1.13 0.61 0.14<br />

MgO 1.18 1.15 1.23 1.28 1.28 1.37 1.37 1.37 2.78 2.91 2.76 2.82 0.54<br />

Gd 2 O 3 1.49 1.27 1.64 1.60 2.94 3.13 1.21<br />

F −0.44 −0.47 0.21 0.24 0.08 −0.01 −0.01 −0.01 1.63 2.34 1.72 1.93 −0.47<br />

V 2 O 5 1.42 1.40 1.85 1.78 1.28<br />

La 2 O 3 0.68 0.66 1.19 1.22 2.70 3.03 0.39<br />

BaO 0.60 0.66 1.22 1.30 2.76 2.66 0.57<br />

CdO 0.98 0.74 1.18 1.15 0.70 2.06 2.43 0.26<br />

NiO 0.40 0.79 1.17 1.14 1.19 3.64 3.01 0.60<br />

Others 1.63 1.77 1.84 1.87 1.77 1.65 1.65 1.65 3.27 2.97 3.02 3.04 1.18<br />

(a) See Table 2 for additi<strong>on</strong>al coefficients.

Author's pers<strong>on</strong>al copy<br />

1822 P. Hrma, S-S. Han / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N<strong>on</strong>-Crystall<strong>in</strong>e Solids 358 (2012) 1818–1829<br />

where N M is the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> major comp<strong>on</strong>ents, N 1 =N M1 +N m is the<br />

number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the n<strong>on</strong>zero first-order coefficients, N M1 is the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

first-order terms for major comp<strong>on</strong>ents, and N m is the number<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> viscosity-affect<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Others. S<strong>in</strong>ce N 2 =<br />

(1/2)N(N+1), while some sec<strong>on</strong>d-order terms can be zero (as <strong>in</strong><br />

Model J described below), N 2 <strong>in</strong>cludes both n<strong>on</strong>zero terms and terms<br />

with B ij =0. The sec<strong>on</strong>d-order coefficients are listed <strong>in</strong> Table 4.<br />

In Model C, we kept all the first-order terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Model B, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

those <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 8 major comp<strong>on</strong>ents (see Table 3). These terms would be,<br />

by Eq. (3), redundant <strong>in</strong> the full sec<strong>on</strong>d-order model. However, because<br />

16 comp<strong>on</strong>ents (SrO, K 2 O, Bi 2 O 3 , MnO, P 2 O 5 , ZnO, PbO, MgO,<br />

Gd 2 O 3 ,F,V 2 O 5 ,La 2 O 3 , BaO, CdO, NiO, and Others) are represented<br />

solely by first-order terms, we reas<strong>on</strong>ed that the lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> miss<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>teracti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these comp<strong>on</strong>ents with the ma<strong>in</strong> comp<strong>on</strong>ents can be mitigated<br />

by reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the first-order terms for the ma<strong>in</strong> comp<strong>on</strong>ents.<br />

Clearly, if an ith comp<strong>on</strong>ent does not <strong>in</strong>teract with any other comp<strong>on</strong>ent,<br />

then B ij ¼ B i for j=1, 2, …, N and, by Eq. (5), Eq. (3) reduces<br />

to identity. However, if <strong>on</strong>ly some comp<strong>on</strong>ents are n<strong>on</strong>-<strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(N>N m >0), then, for the <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g comp<strong>on</strong>ents, the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

terms <strong>in</strong> Eq. (3) does not decrease to <strong>on</strong>ly those <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the double sum<br />

<strong>in</strong> Eq. (7) even <strong>in</strong> the simple case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a symmetrical B ij matrix. Thus,<br />

if (j=1,2,…,N M ) comp<strong>on</strong>ents are <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g and (j=N M +1, N M +<br />

2,…N) comp<strong>on</strong>ents are n<strong>on</strong>-<strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g, then, <strong>in</strong> the case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a symmetrical<br />

Bij<br />

matrix, i.e., Bij<br />

¼ B ji , Eq. (3) becomes B i ¼ PNM<br />

B ij x j þ<br />

B i<br />

P N<br />

j¼NMþ1<br />

x j . Hence, the n<strong>on</strong>-<strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g comp<strong>on</strong>ents <strong>in</strong>fluence the<br />

<strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g <strong>on</strong>es by their very presence <strong>in</strong> the mixture. Obviously,<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g this expressi<strong>on</strong> <strong>in</strong>to Eq. (2) will not lead to Eq. (7).<br />

j¼1<br />

C<strong>on</strong>sequently, the empirical coefficients, B ij , <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Eq. (7) are not equivalent<br />

to the averaged partial specific activati<strong>on</strong> energies, B ij ,def<strong>in</strong>ed by<br />

Eq. (3). A better understand<strong>in</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Eq. (7) is view<strong>in</strong>g it as a first-order<br />

model augmented with sec<strong>on</strong>d-order terms.<br />

3.2. Descripti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> models<br />

The basel<strong>in</strong>e Model C has 61 coefficients. After fitt<strong>in</strong>g it to data, the<br />

number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> outliers stabilized at Δ 2 >3.3 × 10 5 K 2 with 6239 data<br />

po<strong>in</strong>ts accepted. Thus, Model C fitted 346 more data than the firstorder<br />

Model B and 330 more than Model A, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that some<br />

first-order model outliers (~5% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the database) were excluded because<br />

first-order models do not take <strong>in</strong>to account comp<strong>on</strong>ent <strong>in</strong>teracti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

The x i ranges <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Model C rema<strong>in</strong>ed the same as for the firstorder<br />

models, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that first-order-model outliers accepted as<br />

valid by the sec<strong>on</strong>d-order model lay with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ner compositi<strong>on</strong><br />

regi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Ten versi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the sec<strong>on</strong>d-order model were subsequently developed.<br />

These models are versi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Model C truncated by various<br />

means—see Tables 3 and 4. Only <strong>on</strong>e model (Model K) was fitted to<br />

the orig<strong>in</strong>al base <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6755 data. The other n<strong>in</strong>e models were fitted to<br />

a reduced base. This was d<strong>on</strong>e <strong>in</strong> two steps. First, we removed 516<br />

outliers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Model C from the orig<strong>in</strong>al database. Then, we removed<br />

glasses with excessive c<strong>on</strong>tent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> otherwise m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents, because<br />

large fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these comp<strong>on</strong>ents can br<strong>in</strong>g about n<strong>on</strong>l<strong>in</strong>ear<br />

effects <strong>on</strong> viscosity while typical HLW glasses do not c<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> excessive<br />

fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these comp<strong>on</strong>ents. As seen <strong>in</strong> Table 5, the maximum<br />

fracti<strong>on</strong> (x iM )<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Bi 2 O 3 ,V 2 O 5 , PbO, SrO, Gd 2 O 3 , BaO, MnO, and La 2 O 3<br />

exceeded the average fracti<strong>on</strong> (x ia ) by more than 20 times. Thus, we<br />

proceeded by remov<strong>in</strong>g compositi<strong>on</strong>s with x iM /x ia >20, <strong>on</strong>e comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

Table 4<br />

Summary <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sec<strong>on</strong>d-order coefficients, B ij ,<strong>in</strong>10 4 K.<br />

Model C D E F G H I J K L M<br />

SiO 2 × SiO 2 0.33 0.40 0.43 0.27 0.58 0.69 3.89 4.13 3.90 3.85 −0.59<br />

SiO 2 ×Na 2 O −1.26 −1.43 −1.58 −1.66 −1.86 −1.54 −0.12 −2.37 −0.25 −0.02 −3.63<br />

SiO 2 ×B 2 O 3 −0.97 −1.10 −1.29 −1.28 −1.23 −1.22 1.95 1.58 1.60 −2.75<br />

SiO 2 ×Al 2 O 3 0.51 0.66 0.74 0.88 0.90 0.92 7.68 9.47 7.87 7.70 −1.06<br />

SiO 2 ×Fe 2 O 3 0.45 0.56 0.56 0.62 1.31 1.42 4.80 5.15 4.94 4.80 −1.44<br />

SiO 2 × ZrO 2 1.62 1.79 1.97 2.29 3.15 3.08 7.25 9.79 7.73 7.59<br />

SiO 2 ×Li 2 O −4.59 −4.78 −4.95 −5.11 −5.74 −5.81 −8.98 −10.99 −9.17 −8.65 −7.07<br />

SiO 2 × CaO −0.49 −0.44 −0.38 −0.56 −1.17 −1.40 1.72 1.46 1.73 −2.00<br />

Na 2 O×Na 2 O 1.87 1.92 1.95 1.99 1.93 1.89 2.76 4.42 2.93 2.71<br />

Na 2 O×B 2 O 3 −1.90 −2.02 −2.03 −1.95 −2.42 −2.70 −0.84 5.10 −0.88 −0.93 −4.19<br />

Na 2 O×Al 2 O 3 0.29 0.19 0.10 0.14 0.21 0.54 2.74 2.17 2.59<br />

Na 2 O×Fe 2 O 3 1.81 1.80 1.77 1.96 2.28 2.33 2.80 2.53 2.23<br />

Na 2 O×ZrO 2 1.86 1.95 1.95 1.96 2.10 2.15 3.65 2.52 2.79<br />

Na 2 O×Li 2 O 12.05 12.12 12.10 11.97 11.81 11.73 11.75 18.86 13.21 11.56 9.58<br />

Na 2 O×CaO 2.96 2.99 3.14 2.96 2.81 2.55 4.36 12.93 5.140 4.57<br />

B 2 O 3 ×B 2 O 3 4.35 4.17 4.28 4.33 4.00 3.83 4.15 6.93 4.76 4.97 2.87<br />

B 2 O 3 ×Al 2 O 3 −1.13 −1.28 −1.31 −1.27 −2.08 −2.26 2.41 2.55 2.45 −2.61<br />

B 2 O 3 ×Fe 2 O 3 1.86 1.87 1.83 2.20 3.02 3.13 2.83 2.74 2.77<br />

B 2 O 3 ×ZrO 2 0.62 0.67 0.68 0.53 0.50 0.65 3.10 2.40 2.23<br />

B 2 O 3 ×Li 2 O 1.16 1.29 1.43 1.45 2.18 2.32 −0.96 −0.40 −1.29<br />

B 2 O 3 ×CaO 1.02 1.06 1.04 0.93 0.68 0.71 2.26 2.13 2.30<br />

Al 2 O 3 ×Al 2 O 3 0.81 0.89 1.10 0.98 1.02 1.13 4.66 3.00 4.36 4.46<br />

Al 2 O 3 ×Fe 2 O 3 1.69 1.73 1.67 1.91 1.97 1.93 6.53 7.54 5.80 6.31<br />

Al 2 O 3 ×ZrO 2 0.46 0.44 0.45 0.46 0.39 0.42 5.02 5.83 6.38<br />

Al 2 O 3 ×Li 2 O −8.76 −8.83 −8.87 −8.81 −9.12 −9.16 −10.94 −9.44 −11.40 −11.73 −7.78<br />

Al 2 O 3 ×CaO −0.65 −0.84 −0.91 −1.12 −1.45 −1.56 1.24 0.71 0.85 −2.24<br />

Fe 2 O 3 ×Fe 2 O 3 1.17 1.12 1.02 1.43 1.25 0.98 0.31 0.94 0.60 0.84<br />

Fe 2 O 3 ×ZrO 2 0.27 0.02 0.02 −0.09 0.16 0.34 0.35 1.58 1.55<br />

Fe 2 O 3 ×Li 2 O −1.62 −1.52 −1.47 −1.49 −0.91 −0.82 −5.25 −6.93 −7.44<br />

Fe 2 O 3 ×CaO 1.23 1.27 1.35 1.60 1.77 1.93 2.07 1.59 2.03<br />

ZrO 2 ×ZrO 2 −0.92 −0.91 −1.00 −1.17 −1.16 −1.21 −0.50 −0.16 −0.20<br />

ZrO 2 ×Li 2 O −2.63 −2.76 −2.82 −2.79 −3.16 −3.20 −6.39 −13.23 −8.98 −8.80<br />

ZrO 2 ×CaO 1.03 1.09 0.98 0.85 0.48 0.39 2.34 0.58 0.94<br />

Li 2 O×Li 2 O 27.68 27.70 27.79 27.82 28.26 28.36 25.49 23.26 24.77 26.46 30.30<br />

Li 2 O×CaO 5.81 5.89 5.90 6.08 6.19 6.15 5.45 7.12 5.82<br />

CaO ×CaO 0.38 0.47 0.61 0.38 1.14 1.42 1.67 2.02 1.68

Author's pers<strong>on</strong>al copy<br />

P. Hrma, S-S. Han / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N<strong>on</strong>-Crystall<strong>in</strong>e Solids 358 (2012) 1818–1829<br />

1823<br />

Table 5<br />

Maximum and average mass fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents.<br />

Orig<strong>in</strong>al database<br />

Reduced database<br />

x iM x ia x iM /x ia x iM x ia<br />

Bi 2 O 3 0.1618 0.0015 108.6 0.0240 0.0009<br />

V 2 O 5 0.0599 0.0008 72.3 0.0036 0.00003<br />

PbO 0.0967 0.0015 65.4 0.0106 0.0010<br />

SrO 0.2990 0.0061 49.3 0.1010 0.0056<br />

Gd 2 O 3 0.0772 0.0024 31.7 0.0476 0.0024<br />

BaO 0.0471 0.0019 25.0 0.0391 0.0017<br />

MnO 0.1360 0.0056 24.4 0.0702 0.0051<br />

La 2 O 3 0.0500 0.0025 20.4 0.0500 0.0026<br />

CdO 0.0400 0.0020 20.0 0.0400 0.0020<br />

F 0.0600 0.0037 16.4 0.0600 0.0035<br />

P 2 O 5 0.1311 0.0086 15.2 0.1311 0.0087<br />

K 2 O 0.2099 0.0145 14.5 0.1000 0.0142<br />

ZnO 0.0986 0.0092 10.7 0.0821 0.0091<br />

MgO 0.0963 0.0096 10.0 0.0986 0.0092<br />

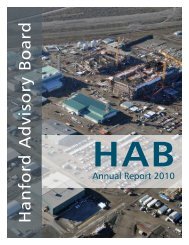

at a time, until the x iM s decreased to values listed <strong>in</strong> Table 5. The maximum<br />

fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all other comp<strong>on</strong>ents except for K 2 O and ZnO<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>ed unaffected. The f<strong>in</strong>al number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data was 5969. Fig. 3 compares<br />

the reduced database with the orig<strong>in</strong>al <strong>on</strong>e. The reduced database<br />

made it possible to further decrease the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> viscosity-affect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

comp<strong>on</strong>ents <strong>in</strong> some models.<br />

To decrease the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> model parameters, we added less<strong>in</strong>fluential<br />

comp<strong>on</strong>ents to Others <strong>in</strong> Models E, F, G, H, K, and L and<br />

removed the first-order terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> major comp<strong>on</strong>ents <strong>in</strong> Models I, J,<br />

K, and L. Also, we removed selected sec<strong>on</strong>d-order terms <strong>in</strong> Models J<br />

and M. F<strong>in</strong>ally, we fitted Models G and H to severely restricted ranges<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data by reduc<strong>in</strong>g the acceptability limit. The 10 model variati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

are briefly characterized below.<br />

Model D. This model is a versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Model C with respect to the k<strong>in</strong>d<br />

and number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ent coefficients except that it was fitted to<br />

the reduced database.<br />

Model E. Here we added to Others m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents V 2 O 5 ,Bi 2 O 3 ,<br />

PbO, Gd 2 O 3 ,BaO,andLa 2 O 3 , for which the value <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> x a |B i −B a |/B a was<br />

smaller than that for Others (8.0).<br />

Model F. In this model, we added to Others all m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents<br />

except SrO, K 2 O, P 2 O 5 , ZnO, MgO, and F.<br />

Model G. With the same set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data and coefficients as <strong>in</strong> Model F,<br />

we restricted the model to data us<strong>in</strong>g a lower acceptability limit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Δ 2 b3.3×10 4 K 2 .<br />

Model H. In this model, we further reduced the acceptability limit<br />

to Δ 2 b3.3×10 3 K 2 .<br />

Model I. To exam<strong>in</strong>e the <strong>in</strong>fluence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the first-order terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

ma<strong>in</strong> comp<strong>on</strong>ents <strong>in</strong> a sec<strong>on</strong>d-order model, we removed these<br />

terms from Model D while keep<strong>in</strong>g the list <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents<br />

unchanged.<br />

Model J. In this versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Model I, we removed less-<strong>in</strong>fluential<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>d-order terms, those with x iM x jM (B ij −B a )/B a b0.399. Also, we<br />

added to Others three m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents, Bi 2 O 3 , PbO, and V 2 O 5 .<br />

Model K. This is the <strong>on</strong>ly sec<strong>on</strong>d-order model other than Model C<br />

fitted to the orig<strong>in</strong>al database. In additi<strong>on</strong> to remov<strong>in</strong>g first-order<br />

terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ma<strong>in</strong> comp<strong>on</strong>ents, we also removed several m<strong>in</strong>or<br />

comp<strong>on</strong>ents and added them to Others.<br />

Model L. Here we removed from Model F the first-order coefficients<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the major comp<strong>on</strong>ents.<br />

Model M. This model is based <strong>on</strong> Model D except that, like Model J,<br />

it does not have B ij coefficients for less-<strong>in</strong>fluential terms (those<br />

with x iM x jM (B ij −B a )/B a b0.07) and V 2 O 5 was added to Others.<br />

The comp<strong>on</strong>ent coefficients for all models are listed <strong>in</strong> Tables 3<br />

and 4. Table 3 also lists values <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> A, R 2 , p, and other parameters.<br />

4. Comp<strong>on</strong>ent effects<br />

4.1. Comp<strong>on</strong>ent replacement and comp<strong>on</strong>ent additi<strong>on</strong><br />

To determ<strong>in</strong>e the kth comp<strong>on</strong>ent effect, we first s<strong>in</strong>gle this comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

out, rewrit<strong>in</strong>g Eq. (7) as<br />

B ¼ B k x k þ ∑ B i x i þ B kk x 2 k þ x k ∑ B ik x i þ XN M X N M<br />

B ij x i x j<br />

i≠k<br />

i≠k i≠k j≠k<br />

where the first-order terms B i x i are summed from i=1toi=N 1 (i ≠ k)<br />

and the terms B ik x i are summed from i=1toi=N M (i ≠ k). Sec<strong>on</strong>d, we<br />

obta<strong>in</strong> the derivative with respect to x k as follows<br />

∂B<br />

∂x<br />

¼ B<br />

∂x k þ ∑ B i<br />

i þ 2B<br />

k i≠k ∂x kk x k þ ∑<br />

k i≠k<br />

∂x i<br />

x<br />

∂x j þ ∂x !<br />

j<br />

x<br />

k ∂x i<br />

k<br />

þ XN M X N M<br />

B ij<br />

i≠k j≠k<br />

∂x<br />

B ik x i þ x k ∑ B i<br />

ik<br />

i≠k ∂x k<br />

ð8Þ<br />

ð9Þ<br />

B, 10 4 K<br />

2.6<br />

2.4<br />

2.2<br />

2.0<br />

1.8<br />

1.6<br />

1.4<br />

Orig<strong>in</strong>al database<br />

Reduced database<br />

1.2<br />

5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

10 4 /T(K))<br />

Fig. 3. Positi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all data po<strong>in</strong>ts with ηb1050 Pa⋅s and Δ 2 b3.3×10 5 K 2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> orig<strong>in</strong>al<br />

database and reduced database <strong>on</strong> the (T 1 , B) surface.<br />

As Eq. (9) <strong>in</strong>dicates, a comp<strong>on</strong>ent affects B depend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>on</strong> accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to which other comp<strong>on</strong>ents it replaces, i.e., ∂B/∂x k is a functi<strong>on</strong> ∂x i /∂x k<br />

(i≠k). Here we will c<strong>on</strong>sider two simple cases.<br />

1) Comp<strong>on</strong>ent replacement. In the simplest case, an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> x i is<br />

compensated by a decrease <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> another comp<strong>on</strong>ent, for example,<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the K 2 O c<strong>on</strong>tent at the expense <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Na 2 O while the c<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g N-2 comp<strong>on</strong>ents rema<strong>in</strong> unchanged.<br />

2) Comp<strong>on</strong>ent additi<strong>on</strong>. Alternatively, a comp<strong>on</strong>ent is added to the<br />

mixture, while fracti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all other comp<strong>on</strong>ents are decreased<br />

<strong>in</strong> equal proporti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Note that compositi<strong>on</strong> changes that <strong>in</strong>crease B also <strong>in</strong>crease η,<br />

provided that T=c<strong>on</strong>stant. This follows from Eqs. (1) and (2). Comb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

these equati<strong>on</strong>s and us<strong>in</strong>g Eq. (5), we can write ln η ¼ PN<br />

f i x i ,<br />

where f i =A+B i /T. Thus, at any temperature at which ηb10 3 Pa s,<br />

the i th comp<strong>on</strong>ent for ln(η), f i , is proporti<strong>on</strong>al to the corresp<strong>on</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<br />

i th comp<strong>on</strong>ent for B.<br />

The follow<strong>in</strong>g two secti<strong>on</strong>s deal with the two cases, comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

replacement and comp<strong>on</strong>ent additi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

i¼1

Author's pers<strong>on</strong>al copy<br />

1824 P. Hrma, S-S. Han / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N<strong>on</strong>-Crystall<strong>in</strong>e Solids 358 (2012) 1818–1829<br />

4.2. Comp<strong>on</strong>ent replacement: Chang<strong>in</strong>g x k for x j<br />

In the case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> chang<strong>in</strong>g x k for x j , we have dx j /dx k =−1 and dx i /<br />

dx k =0 for all i ≠ j and i ≠ k. Thus, Eq. (9) yields<br />

∂B<br />

∂x k<br />

¼ B k −B j þ B kk x k −B jj x j þ XN M<br />

∂ 2 B<br />

∂x 2 k<br />

The sec<strong>on</strong>d derivative is<br />

<br />

<br />

¼ 2 B kk −B kj þ B jj<br />

i¼1<br />

B ik x i − XN M<br />

B ij x i<br />

i¼1<br />

ð10Þ<br />

ð11Þ<br />

For the first-order model, Eq. (10) reduces to a simple relati<strong>on</strong>, ∂B/<br />

∂x k =B k −B j , whereas for the sec<strong>on</strong>d-order model, the comp<strong>on</strong>ent effect<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sists <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> multiple terms even <strong>in</strong> the simple case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> exchang<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>on</strong>e comp<strong>on</strong>ent with another. This is because each major comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

affects each other.<br />

4.3. Comp<strong>on</strong>ent additi<strong>on</strong>: add<strong>in</strong>g x k to mixture<br />

In the case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the kth comp<strong>on</strong>ent added to the mixture, c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all other comp<strong>on</strong>ents rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the same proporti<strong>on</strong>s as <strong>in</strong><br />

the reference mixture. Hence,<br />

∂x i<br />

¼ −<br />

x iR<br />

∂x k<br />

1−x kR<br />

ð12Þ<br />

where the subscript R denotes the reference mixture. Then Eq. (9)<br />

becomes<br />

∂B<br />

¼ B<br />

∂x k þ 2B kk x k þ ∑ B ik x i<br />

k i≠k<br />

−<br />

∑<br />

i≠k<br />

B i x iR þ x k ∑ B ik x iR þ XN M<br />

i≠k<br />

i≠k<br />

1−x kR<br />

X N M<br />

B ij<br />

j≠k<br />

<br />

<br />

x iR x j þ x jR x i<br />

ð13Þ<br />

Comb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Eqs. (8) and (13), we obta<strong>in</strong> for the comp<strong>on</strong>ent effect<br />

at the reference mixture the expressi<strong>on</strong><br />

B k −B R þ B kk x kR − PN M P N M<br />

B ij x iR x<br />

∂B<br />

jR<br />

i≠k j≠k<br />

¼<br />

þ XN M<br />

B<br />

∂x k<br />

1−x ki x iR<br />

ð14Þ<br />

kR<br />

i¼1<br />

<br />

R<br />

This rather complicated expressi<strong>on</strong> simplifies for first-order models<br />

to β i =∂B/∂x i =(B i −B a )/(1−x ia ), where the centroid or average compositi<strong>on</strong><br />

was chosen as reference (B a and x ia are averages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Bs andx i s<br />

for all compositi<strong>on</strong>s with<strong>in</strong> the model compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>— the formulas<br />

are given <strong>in</strong> Secti<strong>on</strong>s 4.6 and 6). Table 6 lists β i values for Models A<br />

and B.<br />

4.4. First-order mixture comp<strong>on</strong>ent classificati<strong>on</strong><br />

Denot<strong>in</strong>g B m and B M as the smallest and the largest experimental<br />

values <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> B <strong>in</strong> the compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>, it follows that comp<strong>on</strong>ents<br />

with B i bB m =1.4×10 4 K decrease and comp<strong>on</strong>ents with B i >B M =<br />

2.4×10 4 K <strong>in</strong>crease the value <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> B when added to any glass with a<br />

compositi<strong>on</strong> with<strong>in</strong> the compositi<strong>on</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

The β i values <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> first-order models allow classificati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> glass<br />

comp<strong>on</strong>ents <strong>in</strong>to the follow<strong>in</strong>g groups:<br />

• Comp<strong>on</strong>ents that str<strong>on</strong>gly decrease B are Li 2 O(β Li2O =−6.0×10 4 K),<br />

F, Na 2 O, and B 2 O 3 .<br />

• Comp<strong>on</strong>ents that moderately decrease B (β i ≤−1.2×10 4 K) are<br />

NiO, CaO, MnO, BaO, and La 2 O 3 .<br />

Table 6<br />

Summary <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ent effects expressed as (B i -B a )/(1-x a )<strong>in</strong>10 4 K.<br />

Model A B Model A B<br />

SiO 2 2.094 2.101 Gd 2 O 3 −0.387 −0.596<br />

Na 2 O −2.185 −2.185 Ce 2 O 3 −0.047<br />

Fe 2 O 3 −0.323 −0.330 F −2.316 −2.343<br />

Al 2 O 3 1.764 1.764 V 2 O 5 −0.454 −0.470<br />

SrO −0.907 −0.863 La 2 O 3 −1.193 −1.213<br />

K 2 O −1.008 −1.079 BaO −1.272 −1.206<br />

B 2 O 3 −1.658 −1.688 Eu 2 O 3 −0.345<br />

CaO −1.354 −1.374 Sm 2 O 3 −0.264<br />

Bi 2 O 3 −0.511 −0.442 CdO −0.890 −1.128<br />

ZrO 2 0.869 0.869 SnO 0.163<br />

UO 2 0.226 NiO −1.479 −1.084<br />

MnO −1.334 −1.415 HfO 2 0.222<br />

P 2 O 5 0.766 0.785 Ga 2 O 3 0.190<br />

TiO 2 −0.555 Y 2 O 3 −0.235<br />

ZnO −0.699 −0.840 CuO −0.583<br />

PbO −0.836 −0.889 Cr 2 O 3 −0.870<br />

MgO −0.694 −0.722 CoO 0.134<br />

Li 2 O −5.990 −5.955 MoO 3 0.031<br />

Nd 2 O 3 0.213 Others −0.247 −0.098<br />

ThO 2 −0.304<br />

• Comp<strong>on</strong>ents that slightly decrease B (β i ≤−0.84×10 4 K) are K 2 O,<br />

SrO, CdO, Cr 2 O 3 , and PbO.<br />

• Comp<strong>on</strong>ents that marg<strong>in</strong>ally decrease B (β i ≤−0.35×10 4 K) are<br />

ZnO, MgO, CuO, TiO 2 ,Bi 2 O 3 ,V 2 O 5 , and Gd 2 O 3 .<br />

• Comp<strong>on</strong>ents that str<strong>on</strong>gly <strong>in</strong>crease B are SiO 2 (β SiO2 =2.1×10 4 K),<br />

Al 2 O 3 , ZrO 2 , and P 2 O 5 .<br />

• All other comp<strong>on</strong>ents listed (Eu 2 O 3 ,Fe 2 O 3 ,ThO 2 ,Sm 2 O 3 ,Y 2 O 3 ,Ce 2 O 3 ,<br />

MoO 3 ,CoO,SnO,Ga 2 O 3 ,Nd 2 O 3 ,HfO 2 ,UO 2 , and those <strong>in</strong> Others) have<br />

a m<strong>in</strong>iscule impact and may <strong>in</strong>crease or decrease B depend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>on</strong><br />

the compositi<strong>on</strong> to which they are added (−0.35×10 4 Kbβ i b<br />

0.25×10 4 K).<br />

Note that out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents (by c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>), <strong>on</strong>ly F<br />

and P 2 O 5 have a str<strong>on</strong>g effect <strong>on</strong> viscosity.<br />

4.5. Model-to-model variati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ent coefficients<br />

Numerous observati<strong>on</strong>s can be made based <strong>on</strong> the comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

coefficients and comp<strong>on</strong>ent effects as listed below.<br />

• The <strong>in</strong>fluence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Others is lower <strong>in</strong> Model B (β Others =−0.10×10 4 K)<br />

than <strong>in</strong> Model A, (β Others =−0.25×10 4 K), even though Others <strong>in</strong><br />

Model B c<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> 15 more comp<strong>on</strong>ents than Others <strong>in</strong> Model A. The<br />

cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this is a mutual compensati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comp<strong>on</strong>ents<br />

with<strong>in</strong> Others.<br />

• Based <strong>on</strong> the comp<strong>on</strong>ent effects, alkali oxides affect B <strong>in</strong> the order<br />

Li 2 ObNa 2 ObK 2 O. No such correlati<strong>on</strong> exists between B i and the<br />

atomic mass <strong>in</strong> other groups <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> oxides, such as MgO–CaO–SrO–<br />

BaO, or TiO 2 –ZrO 2 –HfO 2 –ThO 2 .<br />

• Note that Li 2 O exhibits a str<strong>on</strong>ger n<strong>on</strong>l<strong>in</strong>ear behavior than other<br />

comp<strong>on</strong>ents. It <strong>in</strong>teracts ma<strong>in</strong>ly with SiO 2 ,Al 2 O 3 , and Na 2 O (see<br />

the large B ij values with i≡SiO 2 ,Al 2 O 3 ,Na 2 O, and Li 2 O and j≡Li 2 O).<br />

• As the comparis<strong>on</strong> between the Model C and D coefficients <strong>in</strong>dicates<br />

(see Table 3) and as Fig. 4 illustrates, remov<strong>in</strong>g 270 data<br />

with extreme compositi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> otherwise m<strong>in</strong>or comp<strong>on</strong>ents (called<br />

semim<strong>in</strong>or <strong>in</strong> Fig. 4 legend) had little impact <strong>on</strong> the model while the<br />

R 2 marg<strong>in</strong>ally <strong>in</strong>creased.<br />

• When <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>in</strong>fluential sec<strong>on</strong>d-order comp<strong>on</strong>ents were selected <strong>in</strong><br />

Models J and M, some sec<strong>on</strong>d-order coefficients changed significantly,<br />

as can be seen by compar<strong>in</strong>g the B ij values <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Models I and<br />

J and Models M and D (see Tables 3 and 4).<br />

• Reduc<strong>in</strong>g the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> l<strong>in</strong>ear terms had a noticeable effect <strong>on</strong><br />

some first-order coefficients—compare B F (F stands for fluor<strong>in</strong>e)<br />

and B CaO <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Models E and F versus Model D. However, no such strik<strong>in</strong>g<br />

difference appears between Models K and L versus Model I.

Author's pers<strong>on</strong>al copy<br />

P. Hrma, S-S. Han / Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N<strong>on</strong>-Crystall<strong>in</strong>e Solids 358 (2012) 1818–1829<br />

1825<br />

B i , 10 4 K, Model D<br />

4<br />

Major<br />

3<br />

M<strong>in</strong>or<br />

2<br />

Semim<strong>in</strong>or<br />

1<br />

0<br />

-1<br />

-2<br />

-3<br />

-4<br />

-5<br />

-5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4<br />

B i , 10 4 K, Model C<br />

B ji , 10 4 K, Model D<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

-10<br />

-10 0 10 20 30<br />

B ij , 10 4 K, Model C<br />

Fig. 4. Comp<strong>on</strong>ent coefficients based <strong>on</strong> reduced (Model D) versus orig<strong>in</strong>al (Model C) database.<br />

• Remov<strong>in</strong>g the first-order terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> major coefficients that are represented<br />

by the full set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sec<strong>on</strong>d-order terms affects both B i and B ij<br />

coefficients.<br />

Regard<strong>in</strong>g the model-to-model differences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the coefficients, <strong>on</strong>e<br />

can th<strong>in</strong>k about two c<strong>on</strong>tribut<strong>in</strong>g factors:<br />

1) Insufficient coverage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> certa<strong>in</strong> comp<strong>on</strong>ents by data can make their<br />

coefficients sensitive to experimental errors that mimic the effect<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong>. This can also be an un<strong>in</strong>tenti<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>sequence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

changes caused by remov<strong>in</strong>g outliers.<br />

2) Coefficients <strong>in</strong> a mixed first and sec<strong>on</strong>d-order model are not uniquely<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed. Let Q be an arbitrary number and<br />

B ¼ XN<br />

i¼1<br />

B i x i þ XN<br />