Tyger, tyger, burnt out - Australian Heritage Magazine

Tyger, tyger, burnt out - Australian Heritage Magazine

Tyger, tyger, burnt out - Australian Heritage Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Tyger</strong>, <strong>tyger</strong>, <strong>burnt</strong> <strong>out</strong><br />

The demise of the thylacine<br />

The Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, has acquired almost mythical status since it was hunted to extinction last<br />

century. Once widespread across Tasmania, the <strong>Australian</strong> continent and New Guinea, the thylacine seems<br />

to have been quite susceptible to changes in its habitat, and its fate was sealed when European settlers<br />

decided that it posed an unacceptable threat to their sheep.<br />

BY MARK KELLETT<br />

TALES OF STRANGE<br />

carnivorous beasts lurking in<br />

the forests of Van Diemen’s<br />

Land had been told since<br />

the visit of the Dutch explorer, Abel<br />

Tasman, in 1642. His pilot-major,<br />

Francoys Jacobz, had led a shore party<br />

on the 2nd of December and<br />

described finding “the footing of wild<br />

beasts having claws like a tiger”.<br />

However, his report, as with many<br />

others of strange tracks and halfglimpsed<br />

animals that followed it, is<br />

so vague that modern readers cannot<br />

be certain what animal is being<br />

described (wombats, for example,<br />

have such long claws).<br />

On the 21st of April, 1805, the<br />

Sydney Gazette printed a report of a<br />

strange animal found near the shortlived<br />

settlement at Yorktown on Port<br />

Dalrymple in the north of the island.<br />

An animal of a truly singular and<br />

novel description was killed by dogs<br />

on the 30th of March on a hill<br />

immediately contiguous to the<br />

settlement. From the following<br />

minute description of which, by<br />

Lieutenant Governor PATERSON, it<br />

must be considered of a species<br />

perfectly distinct from any of the<br />

animal creation hitherto known, and<br />

certainly the only powerful and<br />

terrific of the carnivorous and<br />

voracious tribe yet discovered on any<br />

part of New Holland or its adjacent<br />

islands.<br />

Paterson’s detailed description is the<br />

first indisputable account of an animal<br />

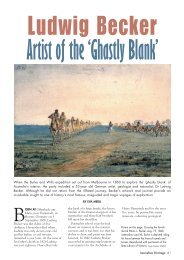

PICTURE ABOVE: Male and female of the<br />

Thylacinus cynocephalus. (1841), H. C.<br />

Richter. From Mammals of Australia by John<br />

Gould (1804–1881). Even at this early<br />

date, Gould was pessimistic ab<strong>out</strong> the<br />

thylacine’s survival. National Library of Australia,<br />

nla.pic-vn3292764.<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> 73

that was to become despised by, and<br />

later emblematic of the people of the<br />

island.<br />

It is very evident that this species is<br />

destructive, and lives entirely on<br />

animal food; as on dissection his<br />

stomach was found filled with a<br />

quantity of kangaroo, weighing 5lbs,<br />

the weight of the whole animal 45lbs.<br />

From its interior structure it must be<br />

a brute peculiarly quick of digestion;<br />

the dimensions were, ... length of the<br />

eye, which is remarkably large and<br />

black, 1 3 / 4 inches; ... length of the<br />

tail, 1 foot 8 inches; length of the<br />

fore leg 11 inches; and of the fore<br />

foot, 5 inches; the fore foot with 5<br />

blunt claws; ... stripes across the back<br />

20, on the tail 3; 2 of the stripes<br />

extend down each thigh; length of<br />

the hind leg from the heel to the<br />

thigh, 1 foot; length of hind foot, 6<br />

inches; the hind foot with 4 blunt<br />

claws, the soles of the feet with<strong>out</strong><br />

hair; ... 8 fore teeth in the upper jaw,<br />

and 6 in the under; 4 grinders of a<br />

side, in the upper and lower jaw; 3<br />

single teeth also in each; 4 tusks, or<br />

canine teeth, length of each 1 inch;<br />

... the body short hair and smooth,<br />

of a greyish colour, the stripes<br />

black; the hair on the neck is<br />

rather longer than that on<br />

the body; the hair on the<br />

ears of a light brown<br />

colour, on the inside<br />

rather long. The form<br />

of the animal is<br />

that of a hyaena, at<br />

the same time<br />

strongly<br />

reminding the<br />

observer of the<br />

appearance of a<br />

low wolf dog.<br />

Van Diemen’s<br />

Land’s first Surveyor-<br />

General, George Harris,<br />

officially described the animal in<br />

1806 on the basis of two male<br />

specimens that had been caught with<br />

traps baited with kangaroo-meat.<br />

Placing it in the same genus as the<br />

American opossums, he gave it the<br />

scientific name of Didelphis<br />

cynocephala (dog-headed opossum).<br />

The creature he described would<br />

come to be known by an astonishing<br />

range of common names, almost all of<br />

them misleading as to its affinities:<br />

legunta, dog-faced dasyurus, hyena<br />

opossum, zebra opossum, Tasmanian<br />

dingo, pouched wolf, striped wolf,<br />

Tasmanian wolf, zebra wolf, and<br />

Tasmanian tiger. In 1824 another<br />

naturalist, Coenraad Temminck,<br />

recognised the animal as distinct from<br />

the American marsupials and gave its<br />

modern name: Thylacinus cynocephalus<br />

(pouched and dog-headed), and<br />

hence thylacine, the common name<br />

now most often used.<br />

The thylacine superficially<br />

resembled a German shepherd dog in<br />

size and shape. However, while dogs<br />

are placental mammals, thylacines<br />

were marsupials related to the<br />

Tasmanian devil, giving birth to up to<br />

four young at an early stage of<br />

development and rearing them in a<br />

backward-facing pouch. In a process<br />

called convergent evolution, the<br />

similar way of life adopted by the<br />

ancestors of thylacines<br />

and dogs led to their<br />

descendants<br />

developing a<br />

similar form.<br />

Zebra, or dog-faced dasyurus. Didelphis<br />

cynocephala. Harris, James Basire, Georges<br />

Cuvier, State Library of Tasmania. Clearly the artist<br />

had not seen the living animal.<br />

There were other important<br />

differences between dogs and<br />

thylacines. Thylacines had a rather<br />

stiffer spine and tail, shorter legs, and<br />

feet that were held flatter to the<br />

ground than dogs of similar size. This<br />

combination of features gave it a<br />

different gait, endowing the animal<br />

with endurance at the expense of<br />

speed. Certainly dogs seem to have<br />

easily caught up with them. Perhaps<br />

misled by the fact that the thylacine’s<br />

front legs are rather shorter than the<br />

rear, R M Martin noted in his History<br />

of Austral-Asia of 1839, “...in running<br />

it bounds like a kangaroo, though not<br />

with such speed.”<br />

The thylacine may have attempted<br />

to catch its prey in an ambush, but if<br />

that failed, it would patiently trot<br />

after its prey. Its persistence was<br />

notable, as a miner named Oscar<br />

described in the Mercury in 1882:<br />

“This native tiger is not swift, and is<br />

very awkward in turning, but it<br />

follows the trail by its never-erring<br />

scent, and in the long run is sure of<br />

its prey.”<br />

When the thylacine caught up with<br />

its prey, usually small kangaroos,<br />

wallabies, possums, sometimes<br />

native rodents, bandicoots, birds,<br />

lizards and even echidnas, its<br />

jaws and teeth were put to<br />

work. Its jaw had the largest<br />

gape of any land mammal and<br />

could close with great force, as<br />

the hunter Hugh Mackay related:<br />

A bull-terrier once set upon a wolf<br />

and bailed it up in a niche in some<br />

rocks. There the wolf stood, with its<br />

back to the wall, turning its head<br />

from side to side, checking the terrier<br />

as it tried to butt in from alternate<br />

and opposite directions. Finally the<br />

dog came in close and the wolf gave<br />

one sharp, fox-like bite, tearing<br />

a piece of the dog’s skull<br />

clean off and it fell<br />

with its brain<br />

protruding, dead.<br />

Like other<br />

carnivorous<br />

marsupials, its fangs<br />

were oval and suited for<br />

crushing, while the<br />

molars were somewhat<br />

primitive and shaped for<br />

cutting (dogs, by contrast, have<br />

slashing canines and a mixture of<br />

slicing and crushing molars).<br />

Thylacine teeth are almost unworn,<br />

supporting records of the marsupial<br />

delicately picking <strong>out</strong> the most<br />

nutritious parts of its prey: the heart,<br />

lungs, liver, kidneys, and if it was<br />

really famished, the muscle from the<br />

inner thighs, leaving the rest for<br />

scavengers like Tasmanian devils.<br />

This fussy diet may have led to the<br />

wholly erroneous belief that the<br />

thylacine fed on blood, first recorded<br />

by British scientist Geoffrey Smith in<br />

1909. This myth doubtless helped to<br />

make the animal an object of hatred<br />

and fear.<br />

Though it is difficult to reconstruct<br />

the behaviour of an extinct animal,<br />

some of the most striking differences<br />

74 <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong>

A rare photograph of one of the last thylacines held in captivity. Like ‘Benjamin’, who was possibly the last member of the species, its end was<br />

probably a lonely one.<br />

between thylacines and dogs might<br />

have been behavioural. It is now<br />

known that many marsupials have a<br />

brain two-thirds the size of placental<br />

mammal of similar size and habit, and<br />

thylacines were no exception to this.<br />

This may have been the result of a<br />

simpler social structure, thylacines<br />

hunted alone or perhaps as a mated<br />

pair or as a mother with joeys, while<br />

dogs form much larger packs. With<br />

less need to communicate, thylacines<br />

do not seem to have vocalised much,<br />

communicating among themselves<br />

with a muted coughing bark and<br />

giving a hissing growl when<br />

antagonised. Ultimately, the<br />

thylacines smaller brain and simpler<br />

behaviour may have reduced its<br />

capacity to adapt to the changes that<br />

overtook it.<br />

The thylacine was the last survivor<br />

of a once successful family. Twelve<br />

fossil members of the thylacine family<br />

are described in a recent paper by<br />

Stephen Wroe, ranging from fox-sized<br />

to wolf-sized predators, most of which<br />

lived between 20 million and 8<br />

million years ago in different parts of<br />

Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea.<br />

Over this period, there seem to have<br />

been between four or five thylacine<br />

species living at any given time. By<br />

the time the first Aboriginal people<br />

arrived some 60,000 years ago, their<br />

fortunes had waned and only the<br />

modern thylacine remained.<br />

Thylacines became extinct in New<br />

Guinea ab<strong>out</strong> 10,000 years ago and in<br />

mainland Australia ab<strong>out</strong> 3,000 years<br />

ago. Although the causes of these<br />

extinctions are not known, the<br />

disappearance of the thylacine in<br />

Australia coincided with the arrival of<br />

the first dingos (Canis familiaris). It<br />

has been suggested that the dingo may<br />

have competed catastrophically with<br />

the mainland thylacine for food and<br />

living space. Though there are<br />

suggestions that small relic thylacine<br />

populations may have persisted on the<br />

mainland, only in Tasmania, isolated<br />

from the mainland by Bass Strait<br />

ab<strong>out</strong> 12,000 years ago, did it survive<br />

to be seen by Europeans with<br />

certainty.<br />

This isolation ended abruptly in<br />

1803 when the British colonised Van<br />

Diemen’s Land in a move to thwart<br />

any territorial ambitions of the<br />

French. A year later Hobart Town<br />

(later Hobart) and Patersonia (later<br />

Launceston) were founded. Two<br />

animals that came in the company of<br />

the settlers were to prove deadly for<br />

the thylacine.<br />

In the chaotic conditions of the<br />

early settlements, some domestic dogs<br />

escaped and formed feral packs. It is<br />

possible that such wild dogs attacked<br />

thylacine; domestic dogs have been<br />

described as being either terrified or<br />

enraged by them. Dogs also would<br />

have competed with thylacines for the<br />

kangaroos and wallabies that made up<br />

the bulk of its diet. Ultimately, the<br />

worst effect of feral dogs on the<br />

thylacine would turn <strong>out</strong> to be an<br />

indirect one.<br />

In the early Tasmanian settlements,<br />

sheep were primarily a food supply for<br />

the colonists, though small numbers of<br />

wool-producing sheep were on the<br />

island as early as 1806. With the<br />

mainland settlements making fortunes<br />

from wool, significant numbers of<br />

merino sheep began to arrive in Van<br />

Diemen’s Land after 1820. There were<br />

some losses among these early flocks<br />

and. although it does not seem<br />

unreasonable that thylacines might<br />

have been responsible for some of<br />

them, reports of spree-kills of sheep<br />

seem more likely to have been the<br />

work of dogs. However, a series of<br />

mistaken human acts ensured that the<br />

thylacine would take the blame.<br />

By 1819, the Van Diemen’s Land<br />

flocks were more than twice the size<br />

of those of the New S<strong>out</strong>h Wales<br />

colonies. Anxious to maintain<br />

investment in the mainland colony,<br />

W C Wentworth wrote ab<strong>out</strong> a wholly<br />

imaginary “animal of the panther<br />

tribe” that “...commits dreadful havoc<br />

among the flocks.”. Unfortunately,<br />

this was misconstrued as a description<br />

of the thylacine, and three years later<br />

the Surveyor General, George<br />

William Evans, paraphrased<br />

Wentworth’s description in the<br />

Description of Van Diemen’s Land.<br />

In 1826 the Van Diemen’s Land<br />

Company was granted extensive<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> 75

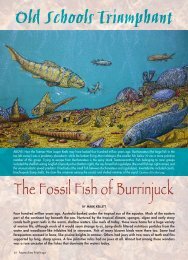

A more accurate portrayal of the thylacine from The Mammals of Australia,1869, Harriet Scott, Thomas Richards, Victor A Pr<strong>out</strong>, Allport Library and<br />

Museum of Fine Arts.<br />

holdings in the north-west of the<br />

island to farm sheep. However, the<br />

land was poorly selected and the sheep<br />

died of exposure or starvation, or were<br />

taken by predators, human and<br />

animal, imported and indigenous.<br />

Ignoring the more serious difficulties,<br />

the company’s directors seized on the<br />

wild predators as a problem they could<br />

solve. In 1830 the company offered<br />

five shillings for male thylacines and<br />

seven for females, with half these<br />

amounts for Tasmanian devils and<br />

feral dogs, an odd choice, considering<br />

that the company’s records indicate<br />

that dogs were responsible for most<br />

kills. The company offered rewards for<br />

thylacines on and off until into the<br />

next century, and other graziers<br />

followed its example. It seems that<br />

this bounty-hunting may have only<br />

reduced thylacine numbers near<br />

inhabited areas, but did set a<br />

precedent for how the animal was to<br />

be dealt with.<br />

Prophetically, the great naturalist,<br />

John Gould, suggested in his classic<br />

Mammals of Australia that the<br />

thylacine might not be able to<br />

withstand such persecution<br />

indefinitely:<br />

When the comparatively small island<br />

of Tasmania becomes more densely<br />

populated, and its primitive forests are<br />

intersected from the eastern to the<br />

western coast, the numbers of this<br />

singular animal will speedily diminish,<br />

extermination will have its full sway,<br />

and it will then, like the Wolf in<br />

England and Scotland, be recorded as<br />

an animal of the past: although this<br />

will be a source of much regret,<br />

neither the shepherd nor the farmer<br />

can be blamed for wishing to rid the<br />

island of so troublesome a creature.<br />

Through the 1880s, the wool<br />

industry was in crisis, and the colonial<br />

government was under pressure to<br />

help the industry. Although a crash in<br />

the price of wool, drought, disease,<br />

rabbit plagues and wild dogs were the<br />

main problems, wealthy farmers’ lobby<br />

groups like the Buckland and Spring<br />

Bay Tiger and Eagle Extermination<br />

Association, the Glamorgan Stock<br />

Protection Association, the Oatlands-<br />

Ross Landowners Association and the<br />

Midlands Stock Protection<br />

Association agitated for the<br />

government to take action against the<br />

thylacine.<br />

They found their voice in the<br />

ambitious Tasmanian House of<br />

Assembly member for Glamorgan,<br />

John ‘Tiger’ Lyne. In 1886, after citing<br />

the inflated figure of “...30,000 or<br />

40,000 sheep were killed annually by<br />

dingoes”, and arguing that since the<br />

thylacines were breeding on crown<br />

land the onus was on the government<br />

to control them, he proposed £500 be<br />

set aside each year for the destruction<br />

of the thylacine, with £1 paid for each<br />

adult thylacine killed and 10 shillings<br />

for each pup. In the face of dissent<br />

ab<strong>out</strong> the cost of the proposal, the bill<br />

was deadlocked. It was only passed<br />

with the vote of the Speaker of the<br />

House, Alfred Dobson, an action<br />

against custom whereby the Speaker is<br />

expected to vote against such a<br />

deadlocked bill. The first bounty was<br />

paid in 1888. Deafness forced Lyne to<br />

retire from politics in 1893, but 2184<br />

thylacines were to be killed as a<br />

consequence of his attempt to seek<br />

the vote of the woolly aristocracy.<br />

The task of hunting the thylacine<br />

fell to ‘tiger men’. The animal’s shy,<br />

solitary and nocturnal nature made it<br />

difficult to hunt. Some trapped the<br />

marsupial with a snare left in a hole in<br />

76 <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong>

a fence or on a forest game trail.<br />

Others used dogs to track and corner<br />

the thylacine.<br />

Tiger men returning from a hunt<br />

took the carcasses to the local police<br />

station, where the ears and toes were<br />

clipped to show that a bounty had<br />

been paid. Farmers would sometimes<br />

pay an equivalent bounty for a<br />

thylacine carcass. The carcass itself<br />

seems to have been considered useless.<br />

It has often been said that thousands<br />

of waistcoats were made of the<br />

animal’s pelts, but this seems to be<br />

apocryphal; certainly no such garment<br />

is known to exist now. A few<br />

thylacine-skin rugs were made, and a<br />

rather ghoulish individual made a<br />

pincushion with a thylacine skull.<br />

Not everyone applauded the<br />

slaughter. Like most carnivores, adult<br />

thylacines were wary of man, but joeys<br />

taken young enough could be readily<br />

tamed and trained. In 1842 the<br />

botanist Ronald Gunn described his<br />

experience of raising and taming three<br />

thylacine joeys in the Papers and<br />

Proceedings of the Royal Society of Van<br />

Diemen’s Land. He was a rare voice of<br />

support for the thylacine, asserting “It<br />

seems far from being a vicious animal<br />

at its worst, and the name Tiger or<br />

Hyaena gives a most unjust idea of its<br />

fierceness.”<br />

Zoos had also acted to improve the<br />

thylacine’s reputation. They were kept<br />

locally in Hobart and Launceston, on<br />

the mainland in Sydney, Melbourne<br />

and Adelaide and as far away as<br />

Britain, Germany, Austro-Hungary,<br />

America, India and S<strong>out</strong>h Africa.<br />

They were not regarded as very<br />

glamorous creatures; like most<br />

carnivores in captivity they were<br />

rather smelly, and forcing the animal<br />

to be active during the day made<br />

them lethargic and stressed. Zoos<br />

made no direct contribution to the<br />

conservation of the thylacine, as they<br />

were not kept in such a way as to<br />

encourage breeding in captivity, but<br />

they did act to shift public opinion<br />

away from the belief that the animal<br />

was a blood-drinking monster. There<br />

were tentative calls for its destruction<br />

to be curbed.<br />

By this time the animal was in need<br />

of such protection. Each year the<br />

bounty was in effect, the government<br />

was paying for 100 or so thylacines.<br />

This number halved in 1906 and,<br />

when the bounty was withdrawn in<br />

1909, only two bounties had been<br />

paid. Prices offered by zoos, between<br />

£7 and £8, had something to do with<br />

this. But it was also clear that the<br />

thylacine had undergone an islandwide<br />

population crash. Its exact cause<br />

is not known, though contemporary<br />

reports of thylacines suffering from a<br />

debilitating disease must be<br />

considered a possible cause.<br />

After the Great War it was apparent<br />

the thylacine was very rare. Prices<br />

offered by zoos rose again and again,<br />

London zoo paying £150 for one in<br />

1926. Scientists and naturalists like<br />

Thomas Flynn, Professor of Zoology at<br />

the University of Tasmania, and Clive<br />

Lord, director of the Tasmanian<br />

Museum, patiently fought through a<br />

political smokescreen that the<br />

thylacine was in no danger and a<br />

bureaucratic minefield to have the<br />

thylacine protected. In 1930 they<br />

succeeded in getting a ban on hunting<br />

thylacines during their breeding<br />

season in December and on the<br />

international traffic in live animals.<br />

Yet it was still shot for sport or as a<br />

pest. In the same year a farmer from<br />

Mawbanna named Wilf Batty,<br />

incensed by an adult female<br />

thylacine’s spree in a chicken coop,<br />

became the last man indisputably to<br />

have shot a wild thylacine.<br />

Surprisingly, there is controversy<br />

ab<strong>out</strong> the identity of the last<br />

thylacine in captivity. The female<br />

could either have been sold to the zoo<br />

as a joey by Walter Mullins in 1924<br />

along with her mother and two littermates,<br />

or as an adult in 1933 by Elias<br />

Churchill. It is possible that both are<br />

true, that when the older thylacine<br />

died she was discreetly replaced with<br />

the younger one, as a parent may<br />

replace a child’s beloved budgie to<br />

avoid a fuss.<br />

In 1933 she was visited by David<br />

Fleay, who had unsuccessfully applied<br />

for the position of Director of the<br />

Tasmanian Museum. While in the<br />

Native Tiger of Tasmania shot by Weaver 1869 (Thylacine), 1869. Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.<br />

One of the few photographs of a thylacine from the 19th century.<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> 77

Thylacine: Wilf Batty with animal shot at Mawbanna, 1931. Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Note<br />

the terrified reaction of the dog to Batty’s kill.<br />

vicinity, he gained the zoo’s<br />

permission to enter the animal’s<br />

enclosure and film it. While Fleay was<br />

arranging the camera, the thylacine<br />

crept around and bit him on the<br />

backside. Fleay was more amused than<br />

angry, and carried the scar proudly for<br />

the rest of his days. This incident<br />

produced just over a minute of silent,<br />

black and white footage that is the<br />

only film record of the thylacine.<br />

The last thylacine in captivity died,<br />

alone and neglected, on the 7th of<br />

September, 1936. Ironically, she had<br />

spent the last two months of her life<br />

as what seems to have been the sole<br />

representative of a completely<br />

protected species. Even more<br />

ironically, as the result of an apparent<br />

scam by a Geelong resident named<br />

Frank Darby, she has come to be<br />

known as Benjamin.<br />

It took some time for people to<br />

realise that the thylacine had become<br />

extinct. Books written as late as the<br />

1970s either describe the thylacine as<br />

a living animal or as “possibly<br />

extinct”. Expeditions were sent <strong>out</strong><br />

over the twentieth century, among<br />

them one led by Fleay in 1945, with<br />

their objective gradually changing<br />

from capturing one for a zoo to<br />

proving the continued existence of<br />

the species. However, none of them<br />

yielded anything other than brief,<br />

unverifiable sightings and smudged<br />

prints.<br />

Proving an animal is extinct, like<br />

proving any negative, is difficult. A<br />

rule of thumb commonly accepted<br />

among biologists is that if there has<br />

been no indisputable evidence of an<br />

organism for 50 years, the animal is<br />

considered extinct. Although there is<br />

a background noise of sightings in<br />

Tasmania and even a few on the<br />

mainland and New Guinea, none are<br />

accompanied by indisputable<br />

evidence. When even a recent $1.2<br />

million reward offered by the Bulletin<br />

magazine cannot produce such<br />

evidence, it appears the animal is<br />

indeed extinct.<br />

Ironically, the people whose<br />

ancestors harried the thylacine <strong>out</strong> of<br />

existence have adopted it as a mascot.<br />

A pair of thylacines flanks the<br />

Tasmanian coat of arms and anyone<br />

who wishes to show their pride in<br />

their Tasmanian heritage, from the<br />

environmentalist lobby to big<br />

business, places one on their banner.<br />

It is a pity the animal could not have<br />

gained such status while it was alive,<br />

though perhaps it could only adopt<br />

such a cuddly image by being safely<br />

dead.<br />

In 1999 a team based in the<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Museum led by Michael<br />

Archer sought to reverse this<br />

situation. They hoped to isolate DNA<br />

from a thylacine joey preserved in<br />

spirits in 1866, with the ultimate aim<br />

of cloning the animal and<br />

regenerating the species. Although the<br />

team was able to succeed in its first<br />

goal, and even got as far as<br />

determining the sequence of three<br />

thylacine genes, in 2005 it was<br />

realised that genetic technology is<br />

simply not advanced enough to<br />

achieve Archer’s very ambitious<br />

objective.<br />

What is known ab<strong>out</strong> the thylacine<br />

has been reconstructed from<br />

examination of dead specimens and<br />

from a motley assembly of the<br />

recollections of people who claimed to<br />

know it, most of whom are now dead.<br />

Though this approach is useful, it<br />

leaves many questions unresolved.<br />

When the biology and ecology of the<br />

animal itself are disputed, the forces<br />

that pushed it to extinction must be<br />

similarly unclear. How important was<br />

hunting? How important was landclearing?<br />

How important were dogs;<br />

and if so, was it directly, by hunting,<br />

or indirectly through competition for<br />

food sources? What role, if any, did<br />

disease play?<br />

Any change in the relative<br />

importance of these factors ultimately<br />

alters the answer posed by modern<br />

scientists and naturalists: could the<br />

thylacine have been saved? Since<br />

their predecessors could not even<br />

determine whether the marsupial<br />

should have been saved, the question<br />

will remain unanswered.<br />

The Author<br />

Dr Mark Kellett is a biologist and a<br />

freelance science writer.<br />

Further Reading<br />

Thylacine by David Owen, Allen &<br />

Unwin, 2003.<br />

The Last Tasmanian Tiger by Robert Paddle,<br />

Cambridge University Press, 2000.<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> Marsupial Carnivores: Recent<br />

Advances in Palaeontology by Stephen<br />

Wroe, in Predators with Pouches: the<br />

Biology of Carnivorous Marsupials, edited<br />

by Menna Jones, Chris Dickman &<br />

Mike Archer, CSIRO Publishing, 2003.<br />

Mammals of Australia by John Gould,<br />

annotated by Joan M Dixon,<br />

Macmillan, 1983.<br />

Furred Animals of Australia by Ellis<br />

Troughton, Angus and Robinson, 1946.<br />

The Doomsday Book of Animals by David<br />

Day, Ebury Press, 1981.<br />

Extinct by Anton Gill and Alex West,<br />

Channel 4 Books, 2001 (the television<br />

documentary series is also very useful).<br />

The Thylacine Museum website:<br />

www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine ◆<br />

78 <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong>