Tsu City Groundbreaking Ceremony case - International Center for ...

Tsu City Groundbreaking Ceremony case - International Center for ...

Tsu City Groundbreaking Ceremony case - International Center for ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

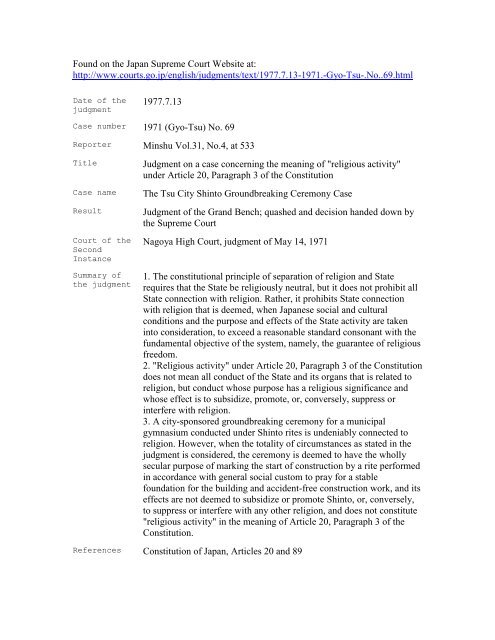

Found on the Japan Supreme Court Website at:<br />

http://www.courts.go.jp/english/judgments/text/1977.7.13-1971.-Gyo-<strong>Tsu</strong>-.No..69.html<br />

Date of the<br />

judgment<br />

1977.7.13<br />

Case number 1971 (Gyo-<strong>Tsu</strong>) No. 69<br />

Reporter Minshu Vol.31, No.4, at 533<br />

Title<br />

Case name<br />

Result<br />

Court of the<br />

Second<br />

Instance<br />

Summary of<br />

the judgment<br />

Judgment on a <strong>case</strong> concerning the meaning of "religious activity"<br />

under Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution<br />

The <strong>Tsu</strong> <strong>City</strong> Shinto <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> Case<br />

Judgment of the Grand Bench; quashed and decision handed down by<br />

the Supreme Court<br />

Nagoya High Court, judgment of May 14, 1971<br />

1. The constitutional principle of separation of religion and State<br />

requires that the State be religiously neutral, but it does not prohibit all<br />

State connection with religion. Rather, it prohibits State connection<br />

with religion that is deemed, when Japanese social and cultural<br />

conditions and the purpose and effects of the State activity are taken<br />

into consideration, to exceed a reasonable standard consonant with the<br />

fundamental objective of the system, namely, the guarantee of religious<br />

freedom.<br />

2. "Religious activity" under Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution<br />

does not mean all conduct of the State and its organs that is related to<br />

religion, but conduct whose purpose has a religious significance and<br />

whose effect is to subsidize, promote, or, conversely, suppress or<br />

interfere with religion.<br />

3. A city-sponsored groundbreaking ceremony <strong>for</strong> a municipal<br />

gymnasium conducted under Shinto rites is undeniably connected to<br />

religion. However, when the totality of circumstances as stated in the<br />

judgment is considered, the ceremony is deemed to have the wholly<br />

secular purpose of marking the start of construction by a rite per<strong>for</strong>med<br />

in accordance with general social custom to pray <strong>for</strong> a stable<br />

foundation <strong>for</strong> the building and accident-free construction work, and its<br />

effects are not deemed to subsidize or promote Shinto, or, conversely,<br />

to suppress or interfere with any other religion, and does not constitute<br />

"religious activity" in the meaning of Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the<br />

Constitution.<br />

References Constitution of Japan, Articles 20 and 89

A Jokoku Appeal was filed by the Appellant seeking reversal in part of<br />

the holding handed down by the Nagoya High Court on May 14, 1971,<br />

on a petition <strong>for</strong> annulment of an administrative disposition, etc., Case<br />

(Gyo-Ko) No. 8 (1967) of the Nagoya High Court. The Jokoku<br />

Appellee sought a judgment dismissing the Jokoku Appeal.<br />

Main text of<br />

the judgment<br />

Reasons<br />

The judgment in part of the Court of Appeals that found against Jokoku<br />

Appellant is quashed. The intermediate appeal of Jokoku Appellee<br />

against that part is dismissed. The costs of the intermediate appeal and<br />

of the Jokoku Appeal shall be borne by Jokoku Appellee.<br />

1. On Ground (1) <strong>for</strong> Jokoku Appeal by Appellant's attorney Horiya<br />

Yoshio:<br />

The language of the petition indicates that the original suit was brought<br />

against the Jokoku Appellant, Kakunaga Kiyoshi, in his capacity as a<br />

private individual. There<strong>for</strong>e, this Court rejects Jokoku Appellant's<br />

argument, which rests on the untenable premise that the original suit<br />

was brought against the Mayor of <strong>Tsu</strong> <strong>City</strong>.<br />

2. On the supplement to the above Ground (1) <strong>for</strong> Jokoku Appeal:<br />

The records clearly show that Jokoku Appellee completed the<br />

necessary petition <strong>for</strong> audit when he brought the original suit. This<br />

Court rejects Jokoku Appellant's argument that the Court of Appeals<br />

erred in its decision.<br />

3. On Ground (2) <strong>for</strong> Jokoku Appeal by Appellant's attorney Horiya<br />

Yoshio and Ground (4) <strong>for</strong> Jokoku Appeal by Appellant's attorney<br />

Higuchi <strong>Tsu</strong>nemichi:<br />

Clearly, an expenditure of public money is illegal not only when the<br />

expenditure itself violates Article 89 of the Constitution, but also when<br />

the reason <strong>for</strong> the expenditure is prohibited under Article 20, Paragraph<br />

3. This Court rejects Jokoku Appellant's contention since it wrongly<br />

assumes that the expenditure of public money in the present <strong>case</strong> would<br />

be illegal only if it violated Article 89 of the Constitution.<br />

4. On Ground (3) <strong>for</strong> Jokoku Appeal of Appellant's attorney Horiya<br />

Yoshio, Grounds (1) and (3) <strong>for</strong> Jokoku Appeal of Appellant's<br />

attorneys Okuno Kenichi, Tanabe <strong>Tsu</strong>nesada, and Hayasegawa<br />

Takeshi, and Grounds (1) and (3) <strong>for</strong> Jokoku Appeal of Appellant's<br />

attorney Higuchi <strong>Tsu</strong>nemichi:<br />

(a) Background of This Case<br />

(i) This <strong>case</strong> contests the legality of the expenditure by Jokoku<br />

Appellant, as Mayor of <strong>Tsu</strong> <strong>City</strong>, of the sum of 7,663 yen in municipal

public funds (4,000 yen in remuneration to Shinto priests and 3,663 yen<br />

<strong>for</strong> offerings) to hold a groundbreaking ceremony at the site of the <strong>Tsu</strong><br />

<strong>City</strong> Gymnasium in Sendo Town, <strong>Tsu</strong> <strong>City</strong>, on January 14, 1965<br />

(hereinafter "<strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong>"). The city, a local public<br />

entity, sponsored the event and used city employees as ushers. The<br />

ceremony was conducted in accordance with Shinto rites and presided<br />

over by four Shinto priests, including the chief priest of Oichi Shrine,<br />

which is a religious corporation.<br />

(ii) The court of first instance ruled that the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong><br />

is the same ceremony that has been conducted since ancient times<br />

under the name jichinsai (Shinto groundbreaking ceremony), and that<br />

while it undeniably appears to be a Shinto religious ceremony, it is<br />

actually a folk ceremony, not a religious activity <strong>for</strong> the purpose of<br />

propagating or disseminating Shinto, and there<strong>for</strong>e does not violate<br />

Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution. Further, that Court found<br />

that the payment of expenses <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> was<br />

not intended to assist a particular religious organization, and that the<br />

payment of 4,000 yen to the Shinto priests, in particular, was merely a<br />

fee <strong>for</strong> services and thus did not violate Article 89 of the Constitution<br />

or Article 138, Paragraph 2 of the Local Autonomy Law.<br />

However, the Court of Appeals ruled that the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong><br />

<strong>Ceremony</strong> cannot be viewed merely as a social observance or folk<br />

ceremony but should be considered a religious rite specific to Shrine<br />

Shinto. The Court further ruled that the Constitution adopts the<br />

principle of complete separation of religion and State and declared the<br />

State to be secular with the intention of making a clear separation<br />

between the two. Accordingly, the Court of Appeals ruled that the<br />

prohibition of "religious activity" in Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the<br />

Constitution covers not only positive acts designed to propagate or<br />

disseminate a particular religion, but all acts that are expressions of<br />

religious faith, including any "religious act, celebration, rite or<br />

practice" as stipulated in Paragraph 2 of Article 20. The Court thus<br />

found that the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> constituted a religious<br />

activity prohibited under Article 20, Paragraph 3, and that the<br />

expenditure of public money by Jokoku Appellant as mayor was<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e illegal.<br />

(iii) Jokoku Appellant contends, in sum, that the Court of Appeals erred<br />

in determining the nature of the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> and the<br />

significance of the principle of religion-State separation when it held<br />

that the ceremony constitutes a religious activity prohibited under<br />

Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution, since the ceremony is<br />

merely a folk practice which, under the name jichinsai, has been<br />

traditionally accepted and per<strong>for</strong>med as a general social custom and<br />

which does not constitute a prohibited religious activity. Jokoku

Appellant contends that the Court of Appeals erred in its interpretation<br />

and application of Article 20, and that these errors clearly influence the<br />

Court's conclusion.<br />

(b) The Judgment of This Court<br />

(i) The Constitutional Principle of Separation of Religion and State<br />

The Constitution guarantees the freedom of religion in a narrow sense<br />

in the provisions "Freedom of religion is guaranteed to all" (Article 20,<br />

Paragraph 1, section 1) and "No person shall be compelled to take part<br />

in any religious act, celebration, rite or practice" (Article 20, Paragraph<br />

2). It also establishes provisions based on the principle of separation of<br />

religion and State (hereinafter "Provisions on Religion-State<br />

Separation"), viz., "No religious organization shall receive any<br />

privileges from the State, nor exercise any political authority" (Article<br />

20, Paragraph 1, section 2); "The State and its organs shall refrain from<br />

religious education or any other religious activity" (Article 20,<br />

Paragraph 3); and "No public money or other property shall be<br />

expended or appropriated <strong>for</strong> the use, benefit or maintenance of any<br />

religious institution or association . . . " (Article 89).<br />

In general, the principle of religion-State separation has been<br />

understood to mean the secularity or religious neutrality of the State; in<br />

other words, because questions of religion and faith are matters of<br />

individual conscience that transcend the dimension of politics, the State<br />

(including local public entities; the same applies hereinafter), as the<br />

holder of secular authority, should place such questions beyond the<br />

realm of public power and refrain from interfering in matters of<br />

religion. The relationship of religion and State differs between<br />

countries and is a product of their historical and social conditions. The<br />

Constitution of the Empire of Japan [1889] (hereinafter "Meiji<br />

Constitution") contained a provision that guaranteed freedom of<br />

religion (Article 28), but the same Article restricted that guarantee<br />

"within limits not prejudicial to peace and order, and not antagonistic to<br />

[the peoples'] duties as subjects." Moreover, State Shinto was virtually<br />

established as the national religion; belief therein was sometimes<br />

demanded, and certain other religious groups were severely persecuted.<br />

Thus, the Meiji Constitution's guarantee of religious freedom was<br />

incomplete.<br />

This situation changed at the end of World War II. On December 15,<br />

1945, the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander <strong>for</strong> the<br />

Allied Powers (GHQ-SCAP) issued the "Directive on the Abolition of<br />

Governmental Sponsorship, Support, Perpetuation, Control, and<br />

Dissemination of State Shinto and Shrine Shinto" (known as the Shinto<br />

Directive) to the Japanese government. This assigned to Shrine Shinto<br />

the same legal status as other religions, and also specified concrete<br />

measures to separate all religions, including Shinto, from the State.

In light of the deleterious effects of the close ties that had existed<br />

between the State and Shinto since the Meiji Restoration, the<br />

Constitution of Japan, promulgated on November 3, 1946, guaranteed<br />

unconditional freedom of belief and further strengthened that guarantee<br />

by establishing the Provisions on Religion-State Separation.<br />

In Japan, unlike Christian or Muslim countries, various religions have<br />

developed alongside one another and coexisted on many levels. In this<br />

environment, an unconditional guarantee of religious freedom, on its<br />

own, would not be sufficient to assure freedom of belief; it was also<br />

necessary to establish the Provisions on Religion-State Separation in<br />

order to eliminate all ties between the State and religion. Thus, the<br />

Constitution should be understood as establishing the Provisions to<br />

secure State secularity and religious neutrality by adopting the ideal of<br />

complete separation of religion and State.<br />

The Provisions on Religion-State Separation are essentially an<br />

institutional guarantee; that is to say, they do not directly guarantee<br />

freedom of religion per se, but attempt to guarantee it indirectly by<br />

securing a system in which religion and the State are separate.<br />

However, religion involves more than private, personal belief; it is<br />

accompanied by a broad array of external social aspects and thus comes<br />

into contact with many sectors of social life, including education, social<br />

welfare, culture, and folk customs. As a natural result of this contact,<br />

the State cannot avoid association with religion as it regulates social<br />

life or implements policies to subsidize and support education, social<br />

welfare, or culture. Thus, complete separation between religion and<br />

State is virtually impossible in an actual system of government.<br />

Furthermore, to attempt complete separation would inevitably lead to<br />

anomalies in every area of social life. For example, it would cast doubt<br />

on the propriety of extending to religiously affiliated private schools<br />

the same subsidies that are given to nonreligious private schools, and it<br />

would call into question the propriety of State assistance to religious<br />

groups <strong>for</strong> the maintenance and preservation of cultural assets such as<br />

shrine and temple buildings, Buddhist statues, and the like. To deny<br />

such support would amount to imposing a disadvantage on these<br />

entities because of their religious affiliation; in other words, it would<br />

amount to discrimination on religious grounds. Similarly, to prohibit all<br />

prison chaplaincy activities of a religious nature would severely restrict<br />

inmates' freedom of worship. As these examples demonstrate, there are<br />

certain inherent and inevitable limits to the religion-State separation<br />

guaranteed by the Provisions. When the principle of religion-State<br />

separation is embodied in an actual system of government, given that<br />

the State must accept some degree of involvement with religion<br />

according to the particular societal and cultural characteristics of the<br />

nation, the question then becomes [a balancing of interests]: under what<br />

circumstances and to what degree can such a relationship be accepted<br />

while remaining consistent with the guarantee of religious freedom

which is the fundamental objective of the system. From this<br />

perspective, the principle of religion-State separation, which <strong>for</strong>ms the<br />

basis of the Provisions and serves to guide their interpretation, demands<br />

that the State be religiously neutral but does not prohibit all connection<br />

of the State with religion. Rather, it should be interpreted as prohibiting<br />

conduct that brings about State connection with religion only if that<br />

connection exceeds a reasonable standard determined by consideration<br />

of the conduct's purpose and effects in the totality of the circumstances.<br />

(ii) Religious Activity Prohibited by Article 20, Paragraph 3<br />

Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution stipulates that "The State<br />

and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other<br />

religious activity." Using the above discussion of the principle of<br />

religion-State separation to interpret this language, "religious activity"<br />

should not be taken to mean all activities of the State and its organs<br />

which bring them into contact with religion, but only those which bring<br />

about contact exceeding the a<strong>for</strong>esaid reasonable limits and which have<br />

a religiously significant purpose, or the effect of which is to promote,<br />

subsidize, or, conversely, interfere with or oppose religion. The prime<br />

example of such activities is the propagation or dissemination of<br />

religion, such as religious education, which is explicitly prohibited in<br />

Article 20, Paragraph 3; but other religious activities like celebrations,<br />

rites, and ceremonies are not automatically excluded if their purpose<br />

and effects are as stated above. Thus, in determining whether a<br />

particular act constitutes proscribed religious activity, external aspects<br />

such as whether a religious figure officiates or whether the proceedings<br />

follow a religiously prescribed <strong>for</strong>m should not be the only factors<br />

considered. The totality of the circumstances, including the place of the<br />

activity, whether the average person views it as a religious act, the<br />

actor's intent, purpose, and degree (if any) of religious consciousness,<br />

and the effects on the average person, should be taken into<br />

consideration to reach an objective judgment based on socially<br />

accepted ideas.<br />

Let us now examine the relationships between Paragraphs 2 and 3 of<br />

Article 20. Both concern religious freedom in the broad sense, but<br />

Paragraph 2, which states that no person shall be compelled to take part<br />

in any religious act, directly guarantees freedom of religion in the<br />

narrow sense as well, that is, against deprivation of that freedom by the<br />

majority. Paragraph 3, on the other hand, seeks to indirectly guarantee<br />

the freedom of religion by the direct prohibition of a certain range of<br />

activities of the State or its organs, thereby guaranteeing a system that<br />

separates religion and State. As indicated above, limits inhere in the<br />

latter guarantee, which should be determined in light of the average<br />

person's attitudes since the issue is one of State involvement with<br />

religion in the social context.

As shown above, the two paragraphs differ in purpose, intent, and<br />

scope, and they guarantee different freedoms. Thus, the interpretations<br />

of "religious act," etc. in Paragraph 2 and "religious activity" in<br />

Paragraph 3 proceed from different perspectives. Not all of the acts<br />

covered by Paragraph 2 are necessarily included in the activities<br />

prohibited by Paragraph 3. Even if a particular religious celebration,<br />

rite, or ceremony is deemed not to be included in "religious activity"<br />

under Paragraph 3, if the State coerced a person to participate who<br />

would otherwise choose not to take part on grounds of religious belief,<br />

this would, of course, infringe that person's religious freedom and<br />

would violate Paragraph 2. For that reason, the above interpretation of<br />

"religious activity" prohibited under Article 20, Paragraph 3 does not in<br />

itself endanger the freedom of belief of religious minorities.<br />

(iii) The <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong><br />

We will now consider whether the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong><br />

constitutes a "religious activity" as prohibited by Article 20, Paragraph<br />

3.<br />

As described by the Court of Appeals, the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong><br />

was clearly a rite per<strong>for</strong>med at the start of construction of a building to<br />

pray <strong>for</strong> a stable foundation <strong>for</strong> the building and safe construction<br />

work. According to the legally relevant facts found by the Court of<br />

Appeals, the <strong>for</strong>m of the ceremony was religious. It was conducted by<br />

Shinto priests, who are professional religionists, at a ceremonial site of<br />

a special type that was set up <strong>for</strong> the occasion; the priests wore<br />

religious garments and followed a ritual specific to Shrine Shinto, using<br />

special ceremonial implements. Moreover, it can be assumed that the<br />

priests who per<strong>for</strong>med the ceremony did so out of religious conviction.<br />

Thus, the ceremony undeniably involved religion.<br />

Nevertheless, although the groundbreaking ceremonies (known as<br />

jichinsai, among other names) that are traditionally per<strong>for</strong>med at the<br />

start of construction work to pray <strong>for</strong> a stable foundation and workers'<br />

safety had religious origins in their intent to pacify the gods of the land,<br />

there can be no doubt that this religious significance has gradually<br />

waned over time. In general, although the ceremony includes prayer <strong>for</strong><br />

safety and a firm foundation at the start of construction, the<br />

proceedings have become a <strong>for</strong>mality perceived as almost completely<br />

devoid of religious meaning. Even if the ceremony is per<strong>for</strong>med in the<br />

style of an existing religion, as long as it remains within the bounds of<br />

well-established and widely practiced usage, most people would<br />

perceive it as a secularized ritual without religious meaning, a social<br />

<strong>for</strong>mality that has become customary at the start of construction work.<br />

Although the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> was conducted as a Shrine<br />

Shinto rite, <strong>for</strong> most citizens, and <strong>for</strong> the Mayor of <strong>Tsu</strong> <strong>City</strong> and others<br />

involved in sponsoring the event, it was a secular occasion with no

particular religious meaning, because such a ceremony is well within<br />

the bounds of general usage widely observed over many years.<br />

Furthermore, in actual practice, the construction workers themselves<br />

who are particularly concerned with safety consider it indispensable, as<br />

a general custom, to mark the start of work with a ceremony sponsored<br />

or attended by the owner of the building and including a ritual like the<br />

one in this <strong>case</strong>. In light of this practice, together with the public<br />

attitudes discussed above, it is clear that the building owner had a very<br />

secular motive <strong>for</strong> holding the customary groundbreaking ceremony:<br />

meeting the demand of construction workers to observe a social<br />

<strong>for</strong>mality that has become customary at the start of work, thereby<br />

ensuring its smooth progress. Since there were no special<br />

circumstances affecting the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong>, there is no<br />

reason to assume that the motive of the Mayor of <strong>Tsu</strong> <strong>City</strong> and others<br />

involved in sponsoring the event was any different from the typical<br />

motive of building owners described above.<br />

The Japanese public in general does not display a great interest in<br />

religion. They reveal, instead, a mixed religious consciousness: as<br />

members of the community, many people are believers in Shinto, and<br />

as individuals, believers in Buddhism. They feel no particular<br />

inconsistency in using different religions on different ceremonial<br />

occasions. Furthermore, Shrine Shinto is characterized by its close<br />

attention to ceremonial <strong>for</strong>m and the virtual absence of outreach<br />

activities such as the active proselytizing seen in other religions. These<br />

circumstances taken together with the public attitude to groundbreaking<br />

ceremonies discussed above render it unlikely that a groundbreaking<br />

ceremony at a construction site, even when per<strong>for</strong>med by Shinto priests<br />

according to the rituals of Shrine Shinto, would raise the religious<br />

consciousness of those attending or of people in general, or that it<br />

would have the effect of assisting, fostering, or promoting Shinto. This<br />

is equally true even when the sponsor of such a ceremony is the State,<br />

acting in the same capacity as a private citizen. It is inconceivable that<br />

such sponsorship would result in the development of a special<br />

relationship between the State and Shrine Shinto, or that it would<br />

ultimately lead to Shinto regaining the status of a State religion, or<br />

otherwise threaten religious freedom.<br />

Considering the totality of the circumstances, although the<br />

<strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> is undeniably connected with religion, we<br />

deem it to be a secular ceremony conducted in accordance with general<br />

social custom at the start of construction work to ensure a stable<br />

foundation and workers' safety. Its effects do not subsidize or promote<br />

Shinto, or, conversely, suppress or interfere with any other religion.<br />

There<strong>for</strong>e, it does not constitute prohibited religious activity under<br />

Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution.<br />

(iv) Summation:

The Court of Appeals erred in interpretation and application of Article<br />

20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution when it reached a determination<br />

different from the above. Since those errors clearly influence the<br />

Court's conclusion, Jokoku Appellant's argument is reasonable.<br />

5. Conclusion<br />

Accordingly, the portion of the judgment of the Court of Appeals that<br />

found against Jokoku Appellant should be quashed. Regarding that<br />

portion, this Court determines as follows: As stated above, the<br />

<strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> does not in any manner violate Article 20,<br />

Paragraph 3 of the Constitution, nor does it violate the second section<br />

of Paragraph 1 of Article 20, since it does not accord any privilege to a<br />

religious organization. Further, in light of the purpose and effects of the<br />

<strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong>, the nature and amount of the expenses<br />

disbursed, and other factors, the payment of ceremony expenses cannot<br />

be regarded as assistance from public funds <strong>for</strong> a particular religious<br />

organization or religious group; it there<strong>for</strong>e does not violate Article 89<br />

of the Constitution, nor does it violate Article 2, Paragraph 15 or<br />

Article 138, Paragraph 2 of the Local Autonomy Law. The petition of<br />

Jokoku Appellee against Jokoku Appellant, which is based on the<br />

premise that the payment is illegal, is thus unsustainable and is<br />

dismissed. This Court affirms the judgment of the court of first<br />

instance, which reached the same conclusion. The portion of the<br />

intermediate appeal finding against Jokoku Appellant is dismissed.<br />

There<strong>for</strong>e, in accordance with Article 7 of the Administrative<br />

Litigation Law, Articles 408, 396, and 384 of the Code of Civil<br />

Procedure, and, with regard to liability <strong>for</strong> the costs of the proceedings,<br />

Articles 96 and 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure, this Court finds as<br />

stated in the Main Text of the Judgment above. The dissenting opinion<br />

of Justices FUJIBAYASHI Ekizo, YOSHIDA Yutaka, DANDO<br />

Shigemitsu, HATTORI Takaaki, and TAMAKI Shoichi follows. The<br />

supplementary dissenting opinion of Justice FUJIBAYASHI Ekizo<br />

follows the main dissenting opinion.<br />

DISSENTING OPINION OF JUSTICES FUJIBAYASHI EKIZO,<br />

YOSHIDA YUTAKA, DANDO SHIGEMITSU, HATTORI<br />

TAKAAKI, AND TAMAKI SHOICHI<br />

1. The Constitutional Principle of Separation of Religion and State<br />

Freedom of religion is the matrix from which the spiritual and<br />

intellectual freedoms of modern humanity have developed. This<br />

important basic human right was a precursor of other civil liberties and<br />

<strong>for</strong>med the nucleus thereof. As a fundamental principle of the life of

the spirit, it is universally guaranteed by the constitutions of modern<br />

nations. In Japan, the Constitution attempts to provide a complete<br />

guarantee of religious freedom. The first section of Paragraph 1 of<br />

Article 20 states unconditionally, "Freedom of religion is guaranteed to<br />

all." The second section of Paragraph 1 then prohibits the granting of<br />

any privileges to or the exercise of any political authority by religious<br />

organizations; Paragraph 2 prohibits compulsory participation in<br />

religious activities; Paragraph 3 prohibits the State and its organs from<br />

engaging in religious activity; and Article 89 prohibits financial aid to<br />

any religious organization or group.<br />

A declaration of unconditional religious freedom is insufficient by<br />

itself to guarantee that freedom. To accomplish that guarantee it is<br />

essential, above all, to sever all ties between religion and State. As long<br />

as such ties exist, there is a great risk that they will lead either to<br />

religious influence over the State or, conversely, to State interference in<br />

religious matters and, ultimately, suppression of religious dissent and<br />

violation of the freedom of belief. This risk is clearly illustrated by the<br />

history of Japan since the Meiji Restoration.<br />

In the first year of the Meiji Period (1868), the new government<br />

proclaimed the unity of religious ritual and government administration.<br />

It reinstated the classical Office of Shinto Worship and announced a<br />

plan to establish Shinto as the State religion, whereby all the shrines<br />

and Shinto priests in Japan were placed under direct government<br />

control. It then issued a series of orders <strong>for</strong> the separation of Shinto and<br />

Buddhism, which were designed to purify Shinto and make it<br />

independent while attacking Buddhism. Meanwhile, the government<br />

maintained virtually unchanged the Tokugawa shogunate's policy of<br />

suppression of Christianity.<br />

In 1870, the government issued the Proclamation of the Great Doctrine,<br />

which declared the "way of the gods" [as the guiding principle of the<br />

State]. In 1872, the Ministry of Religion appointed Shinto priests to the<br />

Agency <strong>for</strong> Spiritual Guidance and issued "three rules <strong>for</strong> teaching": (1)<br />

Observe a spirit of reverence <strong>for</strong> the gods and love of country; (2)<br />

Reveal the laws of nature and the way of humanity. (3) Revere the<br />

Emperor and obey the Imperial court. The government thus<br />

promulgated a political ideology imbued with religious character,<br />

centered on Emperor worship and belief in Shrine Shinto, and took<br />

steps to have the people instructed therein.<br />

In 1871, the government declared that shrines were sites <strong>for</strong> the<br />

observance of "national rites" and were not the private property of<br />

individuals or families (Grand Council of State Decree No. 234). In the<br />

same year, it issued the Grand Council of State Decree No. 235,<br />

"Allocations <strong>for</strong> Government Shrines and Other Shrines and<br />

Employment Regulations, Etc., <strong>for</strong> Shinto Priests," which established a<br />

ranking system <strong>for</strong> all the shrines in Japan (except Ise Shrine). Shrines<br />

were divided into kansha or public shrines (Imperial household shrines

and national shrines) and shosha or miscellaneous shrines (urbanprefectural,<br />

domain [han], prefectural, and village shrines). The decree<br />

also gave Shinto priests the status of public officials, a privilege not<br />

accorded to other religions. In 1875, the government prohibited joint<br />

Shinto-Buddhist proselytizing and ordered each religious sect to<br />

proselytize independently. While giving verbal assurances to Shinto<br />

and Buddhist sects that it would allow freedom of belief, in 1882 the<br />

government abolished the status of Shinto priests as officials of the<br />

Agency <strong>for</strong> Spiritual Guidance and ordered them to cease officiating at<br />

funerals (Ministry of Home Affairs Notices [Otsu] No. 7 and [Tei] No.<br />

1). By requiring Shrine Shinto to engage solely in ritual observances,<br />

the government was able to adopt the official position that it was not a<br />

religion, and on that basis it consolidated a system which, in effect,<br />

established it as the national religion or State Shinto.<br />

Article 28 of the Meiji Constitution (promulgated in 1889) guaranteed<br />

the freedom of religion, but only "within limits not prejudicial to peace<br />

and order, and not in conflict with [the peoples'] duties as subjects."<br />

The Meiji Constitution's guarantee of religious freedom was far from<br />

complete, <strong>for</strong> although the law officially countenanced no state religion<br />

and accorded legal equality to all religions, State Shintoism had<br />

actually already been established, which effectively gave Shrine Shinto<br />

the status of a national religion, as described above, and citizens were<br />

expected to worship at and revere shrines as a civil duty.<br />

Furthermore, Law No. 24 of 1906, the Law Concerning Expenses of<br />

Imperial Household Shrines and National Shrines, stipulated that the<br />

national treasury would be responsible <strong>for</strong> those expenses, and Imperial<br />

Ordinance No. 96 of 1906, "Matters Concerning the Costs of Offerings<br />

by Urban-Prefectural and Lower-Ranking Shrines," stipulated that local<br />

public bodies would finance the costs of the ritual offerings of food,<br />

drink, cloth, and paper made by local shrines. Thus, the shrines were<br />

also made financially dependent on the State or local public entities.<br />

The de facto status of Shrine Shinto as a State religion, there<strong>for</strong>e, was<br />

maintained until Japan's defeat in 1945. During that period, other<br />

religious groups such as Omoto, Hitonomichi, Soka Kyoiku Gakkai<br />

[the prewar name of Soka Gakkai], and the United Church of Christ in<br />

Japan were subjected to strict governmental control and repression.<br />

Religions were officially sanctioned only insofar as they did not<br />

conflict with the concept of a State Shinto-centered "national polity."<br />

Worship at shrines was, in effect, compulsory; not only was this an<br />

egregious violation of the freedom of religion guaranteed under the<br />

Meiji Constitution, but State Shinto also <strong>for</strong>med the spiritual basis of<br />

militarism.<br />

On December 15, 1945, GHQ-SCAP issued the "Directive on the<br />

Abolition of Governmental Sponsorship, Support, Perpetuation,<br />

Control, and Dissemination of State Shinto and Shrine Shinto" (the<br />

Shinto Directive) to the Japanese government, ordering the complete

separation of Shrine Shinto from the State and specifying concrete<br />

measures toward that end. Shrine Shinto was to be placed on the same<br />

legal standing as all other religions; thus, all religions, including<br />

Shinto, were to be separated from the State. There was to be no further<br />

special protection and supervision of Shinto by the State and public<br />

officials, nor public financial aid to Shinto and its shrines. Household<br />

altars and other physical symbols of State Shinto were banned from<br />

public facilities.<br />

The Constitution of Japan incorporated the ideas of the Shinto<br />

Directive in contemplation of the bitter experience of the harmful<br />

effects of close association between the State and Shinto under the<br />

Meiji Constitution's guarantee of religious freedom. That guarantee, as<br />

shown above, was incomplete despite the importance of freedom of<br />

belief as a basic human right. The separation of religion and State is<br />

essential to secure that right. Thus, in addition to the unconditional<br />

guarantee of religious freedom in the first section of Paragraph 1,<br />

Article 20, the Constitution of Japan adopted the provisions cited above<br />

to secure a complete guarantee.<br />

Reviewing the above history, the principle of religion-State separation<br />

embodied in the second section of Paragraph 1 and Paragraph 3 of<br />

Article 20 and in Article 89 would require absolute separation. In other<br />

words, the State should be secular: religion and the State are mutually<br />

independent with no connecting ties, and the State neither allows<br />

religious influence in its affairs nor interferes in religious matters.<br />

The Majority Opinion holds that complete separation of religion and<br />

State is merely an unrealizable ideal. It argues that attempting a<br />

complete separation will result in anomalies in all areas of social life,<br />

and claims that there is an inherent limit to the extent of separation<br />

guaranteed by the Provisions on Religion-State Separation. It argues,<br />

further, that while the separation principle requires State neutrality, it<br />

does not require the State to refrain from all contact with religion. In<br />

the majority's narrow interpretation, conduct that brings connection<br />

with religion is proscribed if that connection, when considered in the<br />

totality of circumstances, is deemed to exceed a standard of<br />

reasonableness based on Japanese social and cultural conditions.<br />

The problem with this approach, however, is that the meaning of State<br />

connection with religion in the Majority Opinion is not entirely clear,<br />

and it is also unclear when such contact would exceed reasonable<br />

limits. In our opinion, the majority's interpretation of the separation<br />

principle poses the danger that State-religion ties will be readily<br />

tolerated and the guarantee of religious freedom itself will be<br />

weakened. Furthermore, from our perspective of an absolute separation<br />

of religion and State, no anomalies would arise if such a separation<br />

were attempted, since activities, like those cited by the majority, which<br />

it claims would be prohibited leading to anomalies in all areas of<br />

society, would in fact be permissible when interpreted under the

principle of equality and other constitutional requirements.<br />

2. Religious Activity Prohibited by Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the<br />

Constitution<br />

Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution states, "The State and its<br />

organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious<br />

activity." Given the significance of religion-State separation described<br />

above, the definition of "religious activity" here should not be limited<br />

to dissemination of religious doctrines, cultivation of converts, and the<br />

like, but also, as a matter of course, should include the act of holding<br />

religious celebrations, ceremonies, or rites. The definition should not<br />

be restricted as the majority contends. Religious celebrations,<br />

ceremonies, and rites are expressions of religious faith, and sponsorship<br />

of such activities by the State or its organs is clearly contrary to the<br />

State secularism signified by the principle of religion-State separation;<br />

inquiry into the concrete effects of the activity is not necessary, as the<br />

majority contends. However, this is not to deny that, in certain<br />

instances, the State or its organs may undertake what could be deemed<br />

to constitute religious activity, either because failure to do so would<br />

restrict citizens' religious freedom or because it is enjoined by<br />

constitutional principles such as equality be<strong>for</strong>e the law.<br />

Even from the above standpoint, it is true that Article 20, Paragraph 3<br />

would not prohibit a ceremony or rite which had religious origins but<br />

which, over time, had completely lost its religious meaning and<br />

coloration and become a purely secular custom. But even customary<br />

observances that retain their religious nature, that is, religious<br />

customary observances, should naturally be included in the category of<br />

prohibited religious activity. (Interpreting and applying Article 20,<br />

Paragraph 3 as described above should essentially determine whether a<br />

custom is secular, not testing whether it meets the ethnological<br />

definition of a custom as stated by the Court of Appeals.)<br />

3. The Nature of the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong><br />

Based on the above, we will now examine whether the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong><br />

<strong>Ceremony</strong> constitutes religious activity prohibited under Article 20,<br />

Paragraph 3 of the Constitution.<br />

(a) The legally relevant facts found by the Court of Appeals are<br />

outlined as follows.<br />

(i) At the site of the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong>, two tents were<br />

erected. Chairs <strong>for</strong> the attendees were placed in rows inside the front<br />

tent, while red and white curtains surrounded the rear tent, sacred<br />

bamboo was placed at its corners, and sacred ropes were hung around it

on three sides to mark the ceremonial area. At the center rear of that<br />

area, an altar consisting of a plain wood table bearing ritual offerings to<br />

the gods was erected. A wooden food-offering stand bearing fruit and<br />

the like was placed at the front of the area. Sacred branches were<br />

placed on a table to the left be<strong>for</strong>e the altar, while the sacred<br />

implements of sprays of the sakaki tree, a sickle, and a hoe, were<br />

placed on a table to the right. Also, upright stems of dry bamboo were<br />

inserted in an area of raked sand at the front left of the altar; in front of<br />

this area, the order of ceremonies was displayed.<br />

(ii) At the site entrance, a city employee poured water on the hands of<br />

each attendee from a ladle decorated with paper ties and ceremonial<br />

paper wrapped around its handle, in what is known as a "hand-washing<br />

ceremony" (the minimum purification rite in Shinto). The attendees<br />

then entered the site of the ceremony.<br />

(iii) The <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> commenced at 10 A.M., with <strong>Tsu</strong><br />

<strong>City</strong> employee Ito Yoshiharu serving as master of ceremonies.<br />

Miyazaki Kisshu, the chief priest of Oichi Shrine, which is a religious<br />

corporation and the local tutelary shrine, officiated in the following<br />

Shinto ritual, assisted by three other Shinto priests, all wearing the<br />

prescribed robes and using ceremonial implements specific to shrines.<br />

The priests conducted various rituals be<strong>for</strong>e the assembled participants:<br />

they per<strong>for</strong>med a ritual waving of sakaki branches to purify them; they<br />

bowed be<strong>for</strong>e the altar and called on divine spirits including Oichi<br />

Hime-no-mikoto, the main god of Oichi and its tutelary deity, to<br />

descend to the offerings placed there; they presented offerings of fruit<br />

and other foods. The officiating priest then stood be<strong>for</strong>e the altar and<br />

read aloud a congratulatory address praying to the divine spirits <strong>for</strong> the<br />

safe completion of the construction work. The site was then ritually<br />

purified and offerings of rice were scattered. The Mayor per<strong>for</strong>med a<br />

ritual gesture of cutting the dry bamboo with the sickle, representing<br />

the clearing of wasteland, and the official in charge of construction<br />

inserted the hoe in the sand, a ritual gesture that represents the leveling<br />

of wasteland. Then, one by one, the Mayor, President of the Municipal<br />

Assembly, and others came be<strong>for</strong>e the altar, offered sakaki sprigs that<br />

were handed to them by a priest, clapped their hands and bowed. The<br />

food offerings were then removed from the altar, and a ritual was<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med inviting the gods to return to the heavens.<br />

The attendees then bowed, the ceremony ended on schedule at<br />

approximately 10:45 A.M., and all proceeded to an adjacent tent on the<br />

western side <strong>for</strong> a celebratory banquet known in Shinto as a naorai.<br />

(ii) It is clear from the above that the groundbreaking was a religious<br />

ceremony conducted according to rituals distinctive to Shrine Shinto<br />

and presided over by a Shinto priest. Setting aside questions of

nomenclature, it is true in general that ceremonies to mark the start of<br />

construction work have been conducted <strong>for</strong> many years and have<br />

become largely secularized over time. However, as can be seen above,<br />

the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> itself had a very strong religious<br />

atmosphere; it cannot possibly be considered a secular convention.<br />

Moreover, even if we consider the concrete effects of the ceremony as<br />

the majority did, it is obvious that a local public entity's sponsorship of<br />

such an event results in preferential treatment and subsidization of<br />

Shrine Shinto. If such activities are condoned, there is a clear risk of a<br />

close relationship developing between local public entities and Shrine<br />

Shinto. We cannot agree with the majority, which admitted the<br />

ceremony's religious connection and did not deny its religious nature,<br />

but which treated its religious significance lightly and underestimated<br />

its effects. In our opinion, the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> clearly<br />

constitutes religious activity under Article 20, Paragraph 3. Moreover,<br />

there are absolutely no grounds as described above <strong>for</strong> allowing such<br />

activity in this <strong>case</strong>. The <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> there<strong>for</strong>e violates<br />

Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution and should not be permitted.<br />

(d) Conclusion<br />

The <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> violates Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the<br />

Constitution. The judgment to that effect by the Court of Appeals was<br />

correct and the Jokoku Appeal should be dismissed.<br />

SUPPLEMENTARY DISSENTING OPINION OF JUSTICE<br />

FUJIBAYASHI EKIZO<br />

1. The State and Religion<br />

The freedom of religion is a great principle of modern democratic<br />

states; it is the quintessence of a spirit of tolerance striven <strong>for</strong> and won<br />

through centuries of political and intellectual conflict. In the historical<br />

process of establishing religious freedom, the separation of religion and<br />

State has come to be considered its indispensable prerequisite. The<br />

principle of religion-State separation consists of two main points:<br />

(a) The State should neither bestow special financial or institutional<br />

support nor impose special restrictions on any religion. In other words,<br />

the State should adopt an equally neutral attitude toward all religions.<br />

(b) The State should not interfere in any way in the religious beliefs of<br />

its citizens. Religious belief should be left to the freedom of each<br />

individual. Whether to believe in a religion, and which religion, if any,<br />

are matters of private choice to be decided by each citizen individually.<br />

With the establishment of these fundamental principles, ties between<br />

the State and a particular religion have come to be rejected, and the<br />

State is required to concern itself solely with secular matters. However,<br />

this does not completely eliminate problems of the State's relationship

with religion. All States have a spiritual or conceptual foundation <strong>for</strong><br />

their existence, and because religion, too, is a product of the human<br />

spirit, the State, while recognizing the principle of religious freedom,<br />

must not itself be indifferent or insensible to religion. The principle of<br />

religious freedom is not a sign of State disregard <strong>for</strong> religion; on the<br />

contrary, it must spring from respect <strong>for</strong> religion.<br />

The existence of the State must be based on truth, and the truth must be<br />

protected. However, it is not the State that determines what the truth is,<br />

nor is it the people. No matter how democratic the age we live in, no<br />

one would consider the truth something to be decided by a majority<br />

vote of the people. What is true is determined by truth itself, and it is<br />

proven true by history, by the long experience of humankind. The truth<br />

is its own evidence, but it is not affirmed as true simply by an assertion<br />

that it is true. Humanity can confirm the truth only by means of history.<br />

For religion, also, we must say that truth is self-evident. Thus, a true<br />

religion can and should stand without support from the State or other<br />

secular authority. In matters of religion, it is precisely this<br />

independence which should be respected.<br />

2. The Democratization of Religion<br />

The "Shinto Directive" of GHQ-SCAP concerning State Shinto and<br />

Shrine Shinto contained three important points which became the<br />

foundations of Article 20 of the Constitution:<br />

(a) It recognized shrines as religious in nature. There is, admittedly,<br />

some room <strong>for</strong> doubt as to whether this is completely consistent with<br />

the popular sentiment of the Japanese people. Shrine Shinto has little of<br />

the thought system characteristic of a religion; in many respects, it<br />

expresses simple folk feelings about life. However, some shrine rituals<br />

and acts per<strong>for</strong>med by Shinto priests can be recognized as religious<br />

ceremonies, and that is the issue in the present <strong>case</strong>.<br />

(b) Since Shrine Shinto was deemed to be a religion, the Directive<br />

ordered that State administrative and financial protection of shrines be<br />

abolished in keeping with the principle of separation of religion and<br />

State.<br />

(c) It was understood that once Shrine Shinto was thus separated from<br />

the State, the people were free to believe in it as a religion.<br />

After the Meiji Restoration (1868), as the government set out to<br />

construct a new Japan, it imported institutions and culture from the<br />

West, but as a spiritual foundation it relied on Japan's ancient way of<br />

the gods. Having launched its modernization campaign in this<br />

disorganized fashion, the government then decided, merely <strong>for</strong> reasons<br />

of international and domestic convenience, that Shrine Shinto did not<br />

constitute a religion, so as not to infringe religious freedom, while in<br />

actual fact according it the status of a national religion. Thereafter,

political affairs and education in Japan were conducted in line with this<br />

policy. Regardless of the personal beliefs of the individuals concerned,<br />

it became customary <strong>for</strong> newly appointed Ministers of State to worship<br />

at Ise Shrine; local public officials were ordered to take part as Imperial<br />

messengers in the major festivals of Imperial household shrines and<br />

national shrines; school groups, led by teachers, visited shrines <strong>for</strong><br />

worship; and local residents, as people under the protection of their<br />

community deity, were asked to make donations <strong>for</strong> shrine festivals.<br />

These requirements were, in general, accepted peacefully as customary<br />

practices <strong>for</strong> the following reasons:<br />

(a) Shrine Shinto was a simple religion. It had no organized theology;<br />

its view of the divine was elemental, and it had very few supernatural<br />

or miraculous components. Generally speaking, all is nature and the<br />

human. Because of this simplicity, the general public readily accepted<br />

shrine worship, since it was not perceived as something that infringed<br />

the principle of religious freedom.<br />

(b) Historically, there had been few conflicts between Japanese<br />

Buddhism and Shrine Shinto, either in matters of theory or in daily life;<br />

on the contrary, they had coexisted side by side, cooperating and<br />

intermingling. The doctrine that the Japanese gods were incarnations of<br />

Buddhas and bodhisattvas provided a theoretical basis <strong>for</strong> the harmony,<br />

unity, and coexistence of the deities of the two religions. Some<br />

Buddhist temples had shrines dedicated to a Shinto guardian deity<br />

within their grounds, and most Japanese were, at the same time, both<br />

Buddhists and parishioners of their local Shinto shrine. In other words,<br />

they were content to believe in Buddhism as individuals and worship at<br />

shrines as a people, without finding this duality strange in any way.<br />

This was due partly to the missionary policies of Buddhism and partly,<br />

as stated above, to the simple religious nature of shrines. In any <strong>case</strong>, a<br />

thousand years leading a dual life combining Buddhism and Shrine<br />

Shinto meant the Japanese peoplehad little difficulty accepting the<br />

State's policy toward Shrine Shinto after the Meiji Restoration.<br />

(c) The religious consciousness of the Japanese people developed<br />

within a tradition of Shrine Shinto and Buddhism and was there<strong>for</strong>e not<br />

sufficiently sensitive to the question of religious freedom. As the two<br />

religions are polytheistic or pantheistic, not monotheistic like<br />

Christianity with its personal God, they did not encourage a sense of<br />

the individual person or stimulate the development of concepts of basic<br />

human rights. Thus, they did little to raise awareness of the importance<br />

of religious freedom. This historical circumstance is probably a major<br />

reason why the issue of shrine worship was not viewed as a serious<br />

infringement of the freedom of religion.<br />

3. Religious Activities Prohibited under Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the<br />

Constitution

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution ("Congress<br />

shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or<br />

prohibiting the free exercise thereof; . . .") was probably the greatest<br />

influence on the enactment of Paragraphs 1 and 3 of Article 20 of the<br />

Constitution of Japan. The provisions in the Japanese Constitution go<br />

even further in their proclamation of the principles of religious freedom<br />

and separation of religion and State and indeed are so exhaustive that<br />

there is nothing comparable among the constitutions of the world.<br />

Paragraph 3 provides, "The State and its organs shall refrain from<br />

religious education or any other religious activity." When the<br />

significance of the principle of separation of religion and State, which<br />

should be the guiding standard <strong>for</strong> interpreting this paragraph, is<br />

considered, the provision should be construed as <strong>for</strong>bidding the State<br />

and its organs from engaging in any activity that has a religious<br />

meaning, not only positive activities with a religious purpose, such as<br />

disseminating a religion or cultivating believers, but also religious<br />

celebrations, ceremonies, and rites. The substantive reasons <strong>for</strong> thus<br />

broadly construing the meaning of religious activity are as follows.<br />

It is said that virtually no people known to history has been without a<br />

religion. Of course, "religion" does not necessarily mean the same to<br />

scholars of religion or religious history as it does to scholars of law.<br />

Over the ages, theologians, philosophers, and those who study religions<br />

scientifically have offered so diverse an array of definitions of religion<br />

that there are said to be as many definitions as there are scholars.<br />

Hence, it is hardly surprising that "religion" is not defined anywhere in<br />

the laws of Japan.<br />

In the United States, also, not only is there no definition of "religion" or<br />

"religious" in the Constitution, but the Supreme Court has not defined<br />

those terms when dealing with various religions or religion-like<br />

entities. Instead, it has been satisfied with stating that, whatever the<br />

meaning of these words, the First Amendment does not prohibit<br />

governmental conduct that intervenes in acts that interfere with duties<br />

to society or destroy good order. In other words, the U.S. Supreme<br />

Court found that because law is created to control acts, law cannot<br />

interfere in religious belief or opinions as such, but it can control<br />

religious activity. To put this another way, the Court decided to treat all<br />

religions and religion-like entities as religions under the Constitution,<br />

but to deal only with their external manifestations. (Cf. [ORIGINAL<br />

CHAPTER TITLE NOT CONFIRMED: "What Is a Religion?"] in<br />

Konvitz, Milton R. Religious Liberty and Conscience: A Constitutional<br />

Inquiry, New York, 1968.)<br />

In my opinion, the words "religion" and "religious" in our Constitution<br />

also should be interpreted as broadly as possible. When these terms are<br />

strictly defined or narrowly construed, the guarantee of Article 20 does<br />

not to extend to other religious acts or other acts of an analogous<br />

nature; this not only results in severe restriction of religious freedom,

ut also opens the way to close ties between religion and State.<br />

4. The Nature of the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> at Issue<br />

The Majority Opinion recognizes that a groundbreaking ceremony is a<br />

rite to pray <strong>for</strong> accident-free construction work, etc., and that it includes<br />

the act of prayer. But it states that in the present day, both to average<br />

citizens and to the sponsors of a groundbreaking, it is a secular<br />

ceremony because it has become a mere <strong>for</strong>mality accompanying the<br />

construction of a building. In other words, the majority consider it a<br />

customary practice.<br />

Of course, we must recognize that there are various observances which<br />

were originally religious but which no longer have any religious<br />

meaning in society. The Japanese still place New Year's pine<br />

decorations outside their gates to bring good luck, although the custom<br />

seems to be declining year by year. We can also readily accept that<br />

customs like the Dolls' Festival and Christmas trees are meaningful as<br />

family treats that parents provide <strong>for</strong> children, or as observances to<br />

foster goodwill within a group. These customs have probably lost all<br />

religious significance.<br />

But can we regard the per<strong>for</strong>mance of the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong><br />

under the circumstances described by the Court of Appeals merely as a<br />

way of bringing good luck or a <strong>for</strong>m of entertainment? As the majority<br />

notes, those who are involved in the building work and who are thus<br />

particularly concerned with safety consider it indispensable to hold a<br />

groundbreaking ceremony incorporating rites as in this <strong>case</strong>, and the<br />

sponsors comply with this demand, regardless of their own wishes, to<br />

ensure the smooth progress of the work. It is inconceivable that the<br />

ceremony in the present <strong>case</strong> was held merely <strong>for</strong> the sake of the<br />

banquet that traditionally follows it. Something is here that cannot be<br />

understood in terms of mere customary practice. In other words, if<br />

consideration <strong>for</strong> workers' safety was the only concern, then given<br />

proper supervision and today's advanced building techniques,<br />

scientifically, nothing further would be necessary. However, a desire to<br />

ensure safety beyond human powers makes it necessary to rely on<br />

something other than human agency. If this is not religious, what is?<br />

Even if the Mayor of <strong>Tsu</strong> <strong>City</strong>, who sponsored the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong><br />

<strong>Ceremony</strong>, is not a believer in any religion, the ceremony does not lose<br />

its religious character, inasmuch as it was an essential requirement to<br />

satisfy the construction personnel's wish <strong>for</strong> a level of safety not<br />

attainable by human powers. Similarly, if a child holds a religious<br />

funeral <strong>for</strong> his or her parent, the funeral is still a religious ceremony<br />

even if that child is not religious.<br />

In the present <strong>case</strong>, a master builder and carpenters did not conduct the<br />

ceremony according to folk practices; four Shinto priests who came in<br />

their professional capacity from a shrine conducted it. The priests were

not merely per<strong>for</strong>mers in an entertainment. According to the facts<br />

ascertained by the Court of Appeals, rituals are of the highest<br />

importance in Shrine Shinto as its central <strong>for</strong>m of expression. All<br />

Shinto scholars emphasize this. It would even be true to say that the<br />

religious activities of shrines consist of holding festivals. Rituals in<br />

Shrine Shinto are gestures of giving thanks to the gods and expressions<br />

of faith in their purest <strong>for</strong>m. In Shrine Shinto, the activities <strong>for</strong> religious<br />

enlightenment consist of festivals, first and last, and any educational<br />

activity that paid no attention to ritual would be considered<br />

meaningless. In other words, in Shrine Shinto ritual is of primary<br />

significance, and ceremonies or ritual observances are religious acts of<br />

the highest order.<br />

5. Human Rights of Religious Minorities<br />

The majority holds that even though the <strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong><br />

was per<strong>for</strong>med according to the rituals of Shrine Shinto by Shinto<br />

priests, who are professional religionists, it would not have raised the<br />

religious consciousness of those attending or of people in general. This<br />

argument probably arises from Shrine Shinto's weak proselytizing<br />

capacity. But even if this is so, it is also a fact that some people feel a<br />

sense of discom<strong>for</strong>t around such ceremonies. An individual or private<br />

corporation is, of course, free to sponsor a groundbreaking ceremony in<br />

accordance with Shrine Shinto or some other religion; that is what<br />

religious freedom means. In the present <strong>case</strong>, however, it is my<br />

impression that too little attention has been paid to the fact that a local<br />

public body sponsored the ceremony. When the power, prestige, and<br />

financial support of the State or a local public body is present behind a<br />

particular religion, this gives rise to indirect pressure on members of<br />

minority religions to submit to the religion that has received public<br />

recognition.<br />

Even if the costs of the ceremony are modest, and even if the general<br />

citizenry is not <strong>for</strong>ced to participate, that is not the issue. (The<br />

<strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> was attended by 150 local dignitaries as<br />

guests; the official in charge of construction was present, <strong>Tsu</strong> <strong>City</strong><br />

employees acted as master of ceremonies and ushers, and a total of<br />

174,000 yen in public monies was spent, including the 7,663 yen in<br />

expenses <strong>for</strong> the ceremony which is the subject of Jokoku Appellee's<br />

petition.)<br />

In short, the State and local public entities should not become involved<br />

in such matters. Even if the minority opinion may be viewed as<br />

hypersensitive, it is not permissible to infringe that minority's freedom<br />

of religion or of conscience by a majority decision. For therein lies the<br />

human right of spiritual freedom, the ultimate minimum that must be<br />

protected as indispensable to the maintenance of democracy. Thomas<br />

Jefferson wrote that religious coercion is clearly distinguished from

coercion in all other matters, <strong>for</strong> one may become rich using methods<br />

that one is <strong>for</strong>ced to follow, and one may be restored to health by<br />

medicines taken against one's will, but one can never be saved by<br />

worshipping a god in whom one does not believe. The State and local<br />

public entities should avoid matters related to religious belief or<br />

conscience that cause social conflict or public controversy. Herein lies<br />

the true significance of the principle of separation of religion and State.<br />

6. The above is my opinion which is in addition to the Dissenting<br />

Opinion. In view of the significance of this Judgment, I wish to note<br />

that in Sections 1 and 2 of this opinion I have quoted extensively from<br />

"Kindai Nihon ni okeru shukyo to minshushugi" (Religion and<br />

democracy in modern Japan) in Yanaihara Tadao zenshu (Collected<br />

works of Yanaihara Tadao), vol. 18, p. 357 ff.<br />

Grand Bench of the Supreme Court<br />

Presiding<br />

Judge<br />

Justice FUJIBAYASHI Ekizo<br />

Justice OKAHARA Masao<br />

Justice AMANO Buichi<br />

Justice KISHIGAMI Yasuo<br />

Justice ERIKUCHI Kiyoo<br />

Justice OHTSUKA Kiichiro<br />

Justice TAKATSUJI Masami<br />

Justice YOSHIDA Yutaka<br />

Justice DANDO Shigemitsu<br />

Justice MOTOBAYASHI Yuzuru<br />

Justice HATTORI Takaaki<br />

Justice TAMAKI Shoichi<br />

Justice KURIMOTO Kazuo<br />

Justices SHIMODA Takeso and KISHI Seiichi are unable to affix their signatures and<br />

seals due to retirement and to illness, respectively.<br />

Presiding Judge, Justice FUJIBAYASHI Ekizo<br />

Translation reference: "Case 34. Kakunaga. v. Sekiguchil (1977). The Shinto<br />

<strong>Groundbreaking</strong> <strong>Ceremony</strong> Case," in The Constitutional Case Law of Japan, 1970<br />

through 1990, eds. Lawrence W. Beer and Hiroshi Itoh (Seattle: University of<br />

Washington Press, 1996), pp. 478-491.<br />

(This translation is provisional and subject to revision.)