Change of paradigms in nephrology--a view back and a look forward.

Change of paradigms in nephrology--a view back and a look forward.

Change of paradigms in nephrology--a view back and a look forward.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Nephrol Dial Transplant (1998) 13: 556–563<br />

Personal Op<strong>in</strong>ion<br />

Nephrology<br />

Dialysis<br />

Transplantation<br />

<strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>paradigms</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>nephrology</strong>—a <strong>view</strong> <strong>back</strong> <strong>and</strong> a <strong>look</strong> <strong>forward</strong><br />

Adalbert Bohle<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Pathology, Tüb<strong>in</strong>gen, Germany<br />

‘Verlernen ist <strong>of</strong>t schwerer als lernen.’ (Arthur normal science is based upon a set <strong>of</strong> concepts or<br />

Koestler)<br />

<strong>paradigms</strong>. Normal science has cumulative character,<br />

(To forget is <strong>of</strong>ten more difficult than to learn.) i.e. <strong>in</strong>volves collect<strong>in</strong>g facts <strong>and</strong> unravell<strong>in</strong>g problems<br />

which confirm the consistency <strong>and</strong> correctness <strong>of</strong><br />

Scientific revolutions by change <strong>of</strong> <strong>paradigms</strong><br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>paradigms</strong>. By necessity, groundbreak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>novations will shake the foundations <strong>of</strong> such tenets<br />

<strong>and</strong> are usually suppressed by normal science.<br />

In his book The structure <strong>of</strong> scientific revolutions, T.S. Nevertheless, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Kuhn, on certa<strong>in</strong> occasions<br />

Kuhn [1] dist<strong>in</strong>guished between great <strong>and</strong> small revolualous<br />

normal science yields results which appear to be anomtions<br />

<strong>in</strong> science <strong>and</strong> subjected such revolutions to more<br />

<strong>and</strong> cannot be reconciled with the predictions<br />

detailed analysis. He came to the conclusion that based on exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>paradigms</strong>. Such anomalies can then<br />

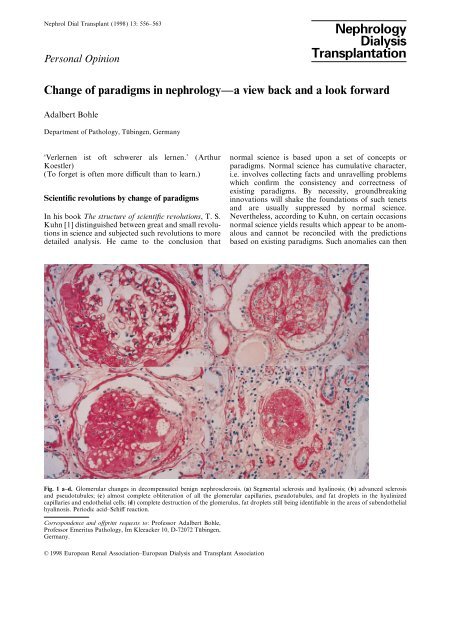

Fig. 1 a–d. Glomerular changes <strong>in</strong> decompensated benign nephrosclerosis. (a) Segmental sclerosis <strong>and</strong> hyal<strong>in</strong>osis; (b) advanced sclerosis<br />

<strong>and</strong> pseudotubules; (c) almost complete obliteration <strong>of</strong> all the glomerular capillaries, pseudotubules, <strong>and</strong> fat droplets <strong>in</strong> the hyal<strong>in</strong>ized<br />

capillaries <strong>and</strong> endothelial cells; (d) complete destruction <strong>of</strong> the glomerulus, fat droplets still be<strong>in</strong>g identifiable <strong>in</strong> the areas <strong>of</strong> subendothelial<br />

hyal<strong>in</strong>osis. Periodic acid–Schiff reaction.<br />

Correspondence <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>fpr<strong>in</strong>t requests to: Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Adalbert Bohle,<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Emeritus Pathology, Im Kleeacker 10, D-72072 Tüb<strong>in</strong>gen,<br />

Germany.<br />

© 1998 European Renal Association–European Dialysis <strong>and</strong> Transplant Association

<strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>paradigms</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>nephrology</strong>—a <strong>view</strong> <strong>back</strong> <strong>and</strong> a <strong>look</strong> <strong>forward</strong> 557<br />

Fig. 3. Interlobular artery from the case described <strong>in</strong> Table 1. There<br />

is stenos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>timal oedema <strong>and</strong> early subendothelial accumulation<br />

<strong>of</strong> smooth-muscle cells <strong>and</strong> fibrocytes. Goldner’s trichrome sta<strong>in</strong>.<br />

compet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>paradigms</strong>. Thus, an anomaly <strong>in</strong> the results<br />

does not lead to a crisis, but to the birth <strong>of</strong> a new<br />

paradigm.<br />

My scientific career was dedicated to renal pathomorphology.<br />

More than 45 000 renal biopsies were<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpreted <strong>in</strong> the context <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical data. Based on<br />

this experience I wish to propose some thoughts that<br />

illustrate how <strong>in</strong>-depth cl<strong>in</strong>icomorphological analysis<br />

forced changes <strong>in</strong> some <strong>paradigms</strong> concern<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> renoparenchymal diseases.<br />

Fig. 2. Decompensated benign nephrosclerosis, uraemic stage (24-<br />

year-old male, blood pressure 195/120 mmHg). There is destruction<br />

<strong>of</strong> juxtamedullary glomeruli <strong>and</strong> marked <strong>in</strong>terstitial fibrosis <strong>and</strong><br />

tubular atrophy <strong>in</strong> the middle layers <strong>of</strong> the cortex.<br />

no longer be disregarded <strong>and</strong> suppressed. Accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to Kuhn, this is the po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> departure <strong>of</strong> extraord<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

science, which puts science on a new basis. Such<br />

episodes which <strong>in</strong>volve a change <strong>of</strong> concepts he called<br />

‘scientific revolutions’. They destroy traditions, <strong>in</strong> contrast<br />

to normal science which is based on ma<strong>in</strong>tenance<br />

<strong>of</strong> traditions. Because <strong>of</strong> such scientific revolutions<br />

scientists are forced to refute time-honoured scientific<br />

theories <strong>in</strong> favour <strong>of</strong> new <strong>paradigms</strong> which apparently<br />

are more successful <strong>in</strong> answer<strong>in</strong>g problems than the<br />

The change <strong>in</strong> concepts concern<strong>in</strong>g vascular lesions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the kidney<br />

Franz Volhard [2] <strong>and</strong> Theodor Fahr [3] analysed<br />

vascular diseases <strong>of</strong> the kidney <strong>and</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>guished<br />

between benign nephrosclerosis <strong>and</strong> malignant<br />

nephrosclerosis. Later, Theodor Fahr dist<strong>in</strong>guished<br />

between a compensated <strong>and</strong> a decompensated form <strong>of</strong><br />

benign nephrosclerosis. By decompensation he implied<br />

that renal function was altered [4]. As a case <strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t,<br />

he described a 55-year-old hypertensive patient who<br />

presented with prote<strong>in</strong>uria <strong>and</strong> erythrocyturia <strong>and</strong> died<br />

<strong>in</strong> renal failure. Apart from benign nephrosclerosis<br />

Table 1. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical data <strong>of</strong> a case <strong>of</strong> primary malignant nephrosclerosis. Patient, a 39-year-old male, suffered 10 days <strong>of</strong> cough, nosebleeds,<br />

<strong>and</strong> diarrhoea<br />

Dialysis Histology I Histology II<br />

Haemoglob<strong>in</strong> (g %) 4.5<br />

Reticulocytes (%) 35<br />

LDH 1380<br />

Platelets 108 000<br />

Bilirub<strong>in</strong> (mg %) 1 3<br />

Creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e (mg %) 28<br />

BUN (mg %) 187<br />

Blood pressure 140/80 140/80 165/85 170/120 230/140<br />

Ur<strong>in</strong>e output (ml ) 100 Anuria Onset <strong>of</strong> 1710<br />

polyuria<br />

Follow-up (days) 1 28 40 56 61 +

558<br />

A. Bohle<br />

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

(c)<br />

(d)<br />

Fig. 4 a–d. Interlobular arteries <strong>in</strong> secondary malignant nephrosclerosis. (a) Early changes, stenos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>timal oedema; (b) stenos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>timal<br />

oedema <strong>and</strong> subendothelial necrosis; (c) late changes, <strong>in</strong>timal fibrosis <strong>and</strong> fresh haemorrhages; (d) Late changes, obliterat<strong>in</strong>g endarteritis.<br />

All the blood vessels are from the same kidney. Goldner’s trichrome sta<strong>in</strong>.<br />

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

(c)<br />

(e)<br />

(d)<br />

(f)<br />

Fig. 5 a–f. Examples <strong>of</strong> severe isolated glomerulopathy with<br />

normal serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration. (a) Control kidney; serum<br />

creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration 1.2 mg%, periodic acid–Schiff reaction.<br />

(b) Acute endocapillary glomerulonephritis with mild acute renal<br />

failure; serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration 1.29 mg%, ur<strong>in</strong>ary output<br />

2450 ml/24 h. (c) Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis<br />

type I; serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration 1.2 mg%, creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e<br />

clearance 90 ml/m<strong>in</strong>, periodic acid–Schiff reaction. (d)<br />

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type I plus chronic<br />

membranous glomerulonephritis; serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration<br />

1.06 mg%, creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e clearance 172 ml/m<strong>in</strong>, periodic acid–Schiff<br />

reaction. (e) Severe nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis; serum<br />

creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration 1.2 mg%, periodic acid–Schiff reaction.<br />

(f ) Perireticular renal amyloidosis; serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration<br />

0.8 mg%, periodic acid–Schiff reaction.

<strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>paradigms</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>nephrology</strong>—a <strong>view</strong> <strong>back</strong> <strong>and</strong> a <strong>look</strong> <strong>forward</strong> 559<br />

attention to this entity [5], which is not <strong>in</strong>frequent.<br />

We have observed this constellation <strong>in</strong> more than 250<br />

cases [6]. Figures 1 <strong>and</strong> 2 show the characteristic<br />

lesions. The glomerular changes (Figure 1) first appear<br />

<strong>in</strong> the juxtamedullary glomeruli, which are not subject<br />

to autoregulation (Figure 2) <strong>and</strong> spread out <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

cortex. Interstitital fibrosis <strong>and</strong> tubular atrophy are<br />

also seen. With the ag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the population <strong>and</strong> longer<br />

survival <strong>of</strong> patients with hypertension, this lesion will<br />

be recognized more frequently, particularly s<strong>in</strong>ce end-<br />

Fahr found glomerular lesions with focal thicken<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> capillaries without cellular proliferation <strong>and</strong> circumscribed<br />

adhesions between glomerular capillaries <strong>and</strong><br />

Bowman’s capsule. Glomerular obsolescence was strik<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

frequent <strong>and</strong> the renal <strong>in</strong>terstitium was fibrosed,<br />

particularly <strong>in</strong> the deep cortex.<br />

Despite such precise description by this pioneer <strong>of</strong><br />

renal pathology, decompensated benign nephrosclerosis<br />

had been completely forgotten as a cause <strong>of</strong><br />

renal dysfunction. We had great difficulty <strong>in</strong> draw<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Fig. 6. Diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Correlations between relative area <strong>of</strong> postglomerular capillaries <strong>and</strong> serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration at<br />

time <strong>of</strong> biopsy.<br />

Fig. 7. Renal amyloidosis. Correlations between relative area <strong>of</strong> postglomerular capillaries <strong>and</strong> serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration at time<br />

<strong>of</strong> biopsy.

560<br />

A. Bohle<br />

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

(c)<br />

(d)<br />

(e)<br />

(f)<br />

(g)<br />

(h)<br />

Fig. 8. (a) Control kidney sta<strong>in</strong>ed with anti-pancytokerat<strong>in</strong>. The<br />

parietal epithelial cells are non-reactive. (b) Immunoreactivity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

podocytes with an antibody aga<strong>in</strong>st viment<strong>in</strong> is demonstrated.<br />

(c) Extracapillary glomerulonephritis. The crescents are reactive<br />

with anti-viment<strong>in</strong>. (d) Extracapillary glomerulonephritis sta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

with anti-pancytokerat<strong>in</strong>. The crescents are non-reactive. (e)<br />

Extracapillary glomerulonephritis. The cells <strong>of</strong> the crescents are<br />

reactive with anti-pancytokerat<strong>in</strong>. (f ) Extracapillary glomerulonephritis.<br />

The basement membrane <strong>of</strong> the glomerular capillaries is<br />

reactive for lam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>. (g) Extracapillary glomerulonephritis with<br />

crescent-shaped collections <strong>of</strong> monocytes/macrophages that sta<strong>in</strong><br />

with the monocyte/macrophage marker PGM 1. (h) Extracapillary<br />

glomerulonephritis. The crescents are non-reactive with the proliferation-associated<br />

antibody MiB1 (Ki67).<br />

had the characteristic histological lesions <strong>of</strong> malignant<br />

nephrosclerosis (Table 1 <strong>and</strong> Figure 3). Currently we<br />

have collected more than 200 cases <strong>of</strong> malignant<br />

nephrosclerosis who had documented normotension at<br />

the start <strong>of</strong> their disease. We designated this entity<br />

‘primary malignant nephrosclerosis’ to dist<strong>in</strong>guish it<br />

from ‘secondary malignant nephrosclerosis’ as a con-<br />

sequence <strong>of</strong> malignant hypertension [9–11]. We feel<br />

that primary <strong>and</strong> secondary malignant nephrosclerosis<br />

can be dist<strong>in</strong>guished <strong>in</strong> that <strong>in</strong> primary malignant<br />

nephrosclerosis all preglomerular vascular lesions are<br />

<strong>of</strong> similar age, whereas <strong>in</strong> secondary malignant<br />

nephrosclerosis the lesions are <strong>of</strong> different ages (Figure<br />

4). It has meanwhile become apparent that primary<br />

malignant nephrosclerosis is the morphological counterpart<br />

<strong>of</strong> the haemolytic–uraemic syndrome. It is more<br />

frequent <strong>in</strong> females (particularly after hormonal con-<br />

traception) <strong>in</strong> contrast to secondary malignant hyper-<br />

tension, which is more frequent <strong>in</strong> males [12].<br />

stage renal failure is by no means <strong>in</strong>frequent <strong>in</strong> the<br />

elderly hypertensive patient [7].<br />

Another example for revision <strong>of</strong> past pathogenetic<br />

concepts is malignant nephrosclerosis. F. Volhard had<br />

assumed that the characteristic obliterative preglomer-<br />

ular vascular lesions are exclusively the result <strong>of</strong> malig-<br />

nant hypertension. Based on one s<strong>in</strong>gle case, i.e. a<br />

young normotensive patient with normal cardiac size<br />

who exhibited malignant nephrosclerosis at autopsy,<br />

Fahr [8] proposed that the vascular lesions were<br />

primary <strong>and</strong> that hypertension was a secondary<br />

consequence. Volhard’s op<strong>in</strong>ion was based on the<br />

observation <strong>of</strong> numerous patients with malignant<br />

hypertension <strong>and</strong> appeared perfectly conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g. We<br />

were satisfied with Volhard’s concept until we exam<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

the renal biopsy <strong>of</strong> a 39-year-old patient who had been<br />

normotensive as documented by daily blood-pressure<br />

measurements over a 4-week period. Nevertheless he<br />

Fig. 9. Corrosion specimen <strong>of</strong> a human kidney after methacrylate<br />

<strong>in</strong>jection under normal pressure. The glomerular capillaries <strong>and</strong> the<br />

dense network <strong>of</strong> postglomerular capillaries are filled with methacrylate.<br />

Scann<strong>in</strong>g electron-microscopy.<br />

What have we learned from the above?<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>icopathological analysis <strong>of</strong> the vascular lesions has<br />

forced us to change the <strong>paradigms</strong> to expla<strong>in</strong> the

<strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>paradigms</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>nephrology</strong>—a <strong>view</strong> <strong>back</strong> <strong>and</strong> a <strong>look</strong> <strong>forward</strong> 561<br />

aetiology <strong>and</strong> the pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> benign nephrosclerosis.<br />

We have also come to learn that <strong>in</strong> malignant<br />

nephrosclerosis the same morphological lesion may be<br />

caused by two entirely different aetiologies.<br />

The role <strong>of</strong> glomerular lesions <strong>in</strong> progression<br />

Fig. 10. Decompensated benign nephrosclerosis with fatty degeneration<br />

<strong>of</strong> endothelial cells. Between the podocyte <strong>and</strong> the basement<br />

membrane from which it has become detached there are basement<br />

membrane lamellae (arrowhead) that are not <strong>in</strong> contact with the<br />

blood-stream but are <strong>in</strong> contact with Bowman’s space. ×5000.<br />

Fig. 11. Proximal tubule with <strong>in</strong>traepithelial lymphocytes, ma<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

T-helper cells (arrowhead).<br />

Classical op<strong>in</strong>ion held that <strong>in</strong> glomerular diseases renal<br />

failure develops when the primary glomerular lesions<br />

have substantially reduced the filtration surface <strong>and</strong><br />

thus led to a reduction <strong>of</strong> glomerular filtration rate.<br />

As a result, histological studies <strong>of</strong> the diseased kidney<br />

focused almost exclusively on the alterations <strong>of</strong> the<br />

glomerulus [13–18]. Morphometric analysis <strong>of</strong> the<br />

kidneys <strong>in</strong> diabetic nephropathy by Mauer et al.[19]<br />

<strong>and</strong> Osterby et al. [20,21] reported a tight correlation<br />

between the filter<strong>in</strong>g surface on the one h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> GFR<br />

on the other.<br />

Very early on [22–24] we were struck by the paradoxical<br />

observation that even severe glomerular lesions <strong>in</strong><br />

glomerular diseases such as endocapillary glomerulonephritis,<br />

membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis,<br />

diabetic glomerulosclerosis, <strong>and</strong> perireticular renal<br />

amyloidosis, were not consistently accompanied by an<br />

elevation <strong>of</strong> serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e if the postglomerular<br />

capillary bed was not compromised [23] (Figure 5).<br />

Such glomerulopathies were associated with progressive<br />

renal failure only when the postglomerular capil-<br />

laries were obliterated by <strong>in</strong>terstitial fibrosis, thus<br />

presumably <strong>in</strong>terfer<strong>in</strong>g with postglomerular blood flow<br />

[23,25,26]. A highly significant <strong>in</strong>verse correlation was<br />

noted between the relative capillary surface <strong>of</strong> the renal<br />

cortex on the one h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e concentration<br />

on the other. We wish to illustrate this diabetic<br />

glomerulosclerosis (Figure 6) <strong>and</strong> perireticular renal<br />

amyloidosis (Figure 7).<br />

Do these observations <strong>of</strong> ours [22,23,25,26] <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

others authors [27,28] force us to change past <strong>paradigms</strong><br />

to expla<strong>in</strong> chronic progressive loss <strong>of</strong> renal<br />

function <strong>in</strong> glomerular disease? I th<strong>in</strong>k yes. In contrast<br />

to many statements <strong>in</strong> literature I do not feel that<br />

glomerular lesions by themselves are sufficient to<br />

expla<strong>in</strong> impaired renal function <strong>in</strong> the majority <strong>of</strong><br />

cases. To take an extreme case: rapidly progressive<br />

extracapillary glomerulonephritis with renal failure. I<br />

do not feel that renal failure is expla<strong>in</strong>ed by obliteration<br />

<strong>of</strong> Bowman’s space by crescents [22]. Crescents consist<br />

not <strong>of</strong> visceral epithelial cells [29,30] (which are postmitotic<br />

<strong>and</strong> cannot proliferate) [31–33], but <strong>of</strong> pluripotent<br />

blood-derived mononuclear cells (Figure 8) [34]<br />

which are trapped <strong>and</strong> accumulate <strong>in</strong> Bowman’s space.<br />

Even <strong>in</strong> its <strong>in</strong>itial stage extracapillary glomerulonephritis<br />

may be accompanied by acute renal failure<br />

[22]. Our belief is strengthened by the observation that<br />

glomerular reserve capacity is so enormous that even<br />

advanced reduction <strong>of</strong> the filtration surface, as documented<br />

by light <strong>and</strong> electron microscopy, does not<br />

necessarily lead to an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> serum creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e [24].<br />

The Achilles’ heel for renal function is not the glomerulus,<br />

but the postglomerular capillary. If this tenet is

562<br />

A. Bohle<br />

correct, it is the lesion <strong>of</strong> the postglomerular vessel Anatomie und Histologie, Vol. 6, 2, 1934, Spr<strong>in</strong>ger, Berl<strong>in</strong>;<br />

that leads to renal failure (Figure 9).<br />

900–934<br />

5. Bohle A, Ratschek M. The compensated <strong>and</strong> decompensated<br />

This concept raises the issue <strong>of</strong> which process dam- form <strong>of</strong> benign nephrosclerosis. Pathol Res Pract 1982; 174,<br />

ages the postglomerular capillaries. Obviously an <strong>in</strong>ter- 357–367<br />

play between altered tubular epithelial cells <strong>and</strong> 6. Bohle A, Christensen J, Grossmann T, Inniger R, Cavalcanti de<br />

<strong>in</strong>terstitial cells leads to <strong>in</strong>terstitial fibrosis [35,36 ]. Oliveira V, Wehrmann M. Über benigne und maligne<br />

Several hypotheses on the genesis <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terstitial fibrosis Nephrosclerosen. Pathologe 1988; 10: 263–271<br />

7. Klag MJ, Whelton PK, R<strong>and</strong>all BL et al. Blood pressure <strong>and</strong><br />

have been proposed, e.g. exposure <strong>of</strong> the lum<strong>in</strong>al end-stage renal disease <strong>in</strong> men. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 13–18<br />

surface <strong>of</strong> tubular epithelial cells to serum prote<strong>in</strong>s as 8. Fahr Th. Über atypische Befunde aus dem Kapitel des Morbus<br />

a result <strong>of</strong> glomerular leakage [37,38]. Several factors Brightii nebst anhangsweisen Bemerkungen zur Hypertonie-<br />

may be <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>and</strong> we proposed one further hypo- frage. Virchows Arch Path Anat u Physiol 1924; 248: 101–102<br />

thesis. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Hawk<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Cochran [39] <strong>and</strong> 9. Bohle A, Helmchen U, Meyer D et al. Über die primäre und<br />

sekundäre maligne Nephrosklerose. Kl<strong>in</strong> Wochenschr 1973; 51:<br />

to McCluskey [40] lesioned glomeruli release an 841–857<br />

autoantigen <strong>in</strong>to Bowman’s space. We presume that 10. Bohle A, Grund KE, Helmchen U, Meyer D. Primary malignant<br />

the site <strong>of</strong> orig<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> this autoantigen is the glomerular nephrosclerosis. Cl<strong>in</strong> Sci 1976; 51: 23–25<br />

epithelial cell [41], which desquamates <strong>and</strong> releases 11. Bohle A, Helmchen U, Grund KE et al. Malignant nephroscl-<br />

GBM material from the basal membrane (Figure 10). erosis <strong>in</strong> patients with hemolytic uremic syndrome (Primary<br />

malignant nephrosclerosis). Curr Top Pathol 1977; 65: 81–113<br />

Such material, which is normally sequestered <strong>and</strong> 12. Bohle A. Paradigmawechsel <strong>in</strong> der Nephrologie. Nieren<br />

cannot be recognized by the immune system, may Hochdruckkrankh 1994; 23: 45–57<br />

become accessible to the immune system after pro- 13. K<strong>in</strong>caid-Smith P, Dowl<strong>in</strong>g JP, Mathews DC. Atlas <strong>of</strong> Glomerular<br />

cess<strong>in</strong>g by tubular epithelial cells <strong>and</strong> by lymphocytes Disease. Morphological <strong>and</strong> Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Correlations. Aids Health<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tertubular location (Figure 11). This hypothesis Science Press, Sydney 1985<br />

14. Meadows K. Renal Histopathology. A Light Microscopic Study<br />

requires confirmation; if it is correct, it would imply <strong>of</strong> Renal Disease. Oxford University Press, New York, 1978<br />

that <strong>in</strong>terstitial fibrosis is the result <strong>of</strong> an autoaggres- 15. Spargo BH, Seymour E, Ordonez NE. Renal Biopsy Pathology<br />

sion process. with Diagnostic <strong>and</strong> Therapeutic Implications. Wiley, New<br />

York, 1980<br />

16. Rotter,W. Farbatlas der Nierenbiopsie. Pathologie glomerulärer<br />

Conclusions<br />

Erkrankungen. Schattauer, Stuttgart, 1983<br />

17. Lawler,W. Glomerular Pathology. Churchill Liv<strong>in</strong>gstone,<br />

What have we learned from a life-time <strong>of</strong> work on<br />

London 1991<br />

18. Steffes MW, Osterby R, Shavers B, Mauer SM. Mesangial<br />

glomerular pathomorphology?<br />

expansion as a central mechanism for loss <strong>of</strong> kidney function <strong>in</strong><br />

It is obvious that <strong>in</strong>tellectual economy requires diabetic patients. Diabetes 1989; 38: 1077–1081<br />

19. Mauer SM, Steffes MW, Ellis EN, Sutherl<strong>and</strong> ER, Brown GM,<br />

work<strong>in</strong>g hypotheses to h<strong>and</strong>le the data provided by<br />

Goetz FC. Structural–functional relationship <strong>in</strong> diabetic nephroobservational<br />

or <strong>in</strong>terventional studies. The above pathy. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Invest 1984; 74: 1149–1185<br />

examples illustrate, however, that we have to keep an 20. Osterby R, Gunderson HJG. Glomerula size <strong>and</strong> structure <strong>in</strong><br />

open m<strong>in</strong>d <strong>and</strong> have to be prepared for the possibility diabetes mellitus: early abnormalities. Diabetes 1975; 25: 872–875<br />

that our concepts <strong>and</strong> <strong>paradigms</strong> may be wrong <strong>and</strong> 21. Hrose K, Tsudica H, Osterby,R, Gunderson HJG. A strong<br />

correlation between glomerular filtration rate <strong>and</strong> filtration<br />

may have to be modified <strong>in</strong> the light <strong>of</strong> new data (or<br />

surface <strong>in</strong> diabetic kidney hyperfunction. Lab Invest 1980; 43:<br />

new <strong>in</strong>terpretations). I feel that the example <strong>of</strong> 434–437<br />

nephrosclerosis <strong>and</strong> primary glomerulopathies is illus- 22. Bohle A, Gärtner HV, Laberke G, Krück, F. Die Niere. Struktur<br />

trative <strong>and</strong> serves to make <strong>in</strong>vestigators humble. The und Funktion. Schattauer Verlag, Stuttgart, 1984; 11<br />

change <strong>of</strong> <strong>paradigms</strong>, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Kuhn, is a pa<strong>in</strong>ful 23. Bohle A, Wehrmann M, Mackensen-Haen S. Pathogenesis <strong>of</strong><br />

chronic renal failure <strong>in</strong> primary glomerulopathies. Nephrol Dial<br />

process <strong>and</strong> may expla<strong>in</strong> why such new concepts <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

1994; 3 [Suppl ]: 4–12<br />

cause controversy <strong>and</strong> are met by fierce opposition. 24. Bohle A, Aeikens B, Eenboom A et al. The structure <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human renal glomerulus with particular reference to the length<br />

Acknowledgements. This article is dedicated to Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Ernst <strong>and</strong> surface area <strong>of</strong> the glomerular capillaries <strong>and</strong> the filtration<br />

Jünger, a great poet, philosopher, <strong>and</strong> morphologist on the occasion area under physiological conditions <strong>and</strong> severe isolated glomerul<strong>of</strong><br />

his 103rd birthday. The text is the written version <strong>of</strong> the Farewell opathies. Am J Nephrol (<strong>in</strong> press)<br />

Lecture at the Eberhard Karl University, Tüb<strong>in</strong>gen on 16 February 25. Bohle A, Gise H v. Mackensen-Haen S, Stark-Jakob B. The<br />

1990. obliteration <strong>of</strong> the postglomerular capillaries <strong>and</strong> its <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

upon the function <strong>of</strong> both glomeruli <strong>and</strong> tubuli. Functional<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpretations <strong>of</strong> morphologic f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. Kl<strong>in</strong> Wochenschr 1981;<br />

References<br />

59: 1043–1051<br />

26. Bohle A, Mackensen-Haen S, Wehrmann M. Significance <strong>of</strong><br />

1. Kuhn TS. Die Struktur wissenschaftlicher Revolutionen. postglomerular capillaries <strong>in</strong> the pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> chronic renal<br />

Suhrkamp Tagebuch Wissenschaft, 1969<br />

failure. Kidney Blood Press Res 1996; 19: 191–195<br />

2. Volhard F. Die doppelseitigen hämatogenen Nierenkrankheiten. 27. Risdon FC, Sloper SA, de Wardener HE. Relationship between<br />

Spr<strong>in</strong>ger, Berl<strong>in</strong>, 1918<br />

renal function <strong>and</strong> histological changes found <strong>in</strong> renal biopsy<br />

3. Fahr Th. Pathologische Anatomie des Morbus Brightii. In: specimens from patients with persistent glomerular nephritis.<br />

Henke F, Lubarsch O. H<strong>and</strong>buch der speziellen pathologischen Lancet 1968; 2: 363–366<br />

Anatomie und Histologie, Vol. 6, 1, 1925, Spr<strong>in</strong>ger, Berl<strong>in</strong>; 28. Scha<strong>in</strong>uck LI, Striker GE, Luther RE, Benditt EP.<br />

177–178<br />

Structural–functional correlations <strong>in</strong> renal diseases. The correla-<br />

4. Fahr Th. Pathologische Anatomie des Morbus Brightii. In: tions. Hum Pathol 1970; 1: 631–641<br />

Henke F, Lubarsch O. H<strong>and</strong>buch der speziellen pathologischen 29. Gabbert H, Thoenes,W. Formation <strong>of</strong> basement membrane <strong>in</strong>

<strong>Change</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>paradigms</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>nephrology</strong>—a <strong>view</strong> <strong>back</strong> <strong>and</strong> a <strong>look</strong> <strong>forward</strong> 563<br />

extracapillary proliferates <strong>in</strong> rapidly progressive glomerulo- GA. Expression <strong>of</strong> HLA-DQ-DR, <strong>and</strong> -DP antigens <strong>in</strong> normal<br />

nephritis. Virchchows Arch [B] 1977; 25: 265–269<br />

kidney <strong>and</strong> glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 1989; 35: 116–124<br />

30. Adler S. Glomerular epithelial cells. In: Neilson EG, Couser 36. Müller GA. Mechanismen der chronischen Nieren<strong>in</strong>suffizienz<br />

WG, ed. Immunologic Renal Diseases. Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott-Raven, und Möglichkeiten zu deren Prävention. Nieren- und<br />

Philadelphia, 1997; 635<br />

Hochdruckkrankh 1977; 26 (6) S231–S239<br />

31. Nagata M, Schärer, K, Kriz W. Glomerular damage after 37. Müller GA, Markovic–Lipkovski J. Muller CA. Intercellular<br />

un<strong>in</strong>ephrectomy <strong>in</strong> young rats. I. Hypertrophy <strong>and</strong> distortion <strong>of</strong> adhesion molecule-l expression <strong>in</strong> human kidneys with glom-<br />

capillary architecture. Kidney Int 1992; 42: 130–147<br />

erulonephritis. Cl<strong>in</strong> Nephrol 1991; 36: 203–208<br />

38. Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P, Benigni A. Underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g the nature<br />

32. Kriz W, Hähnel B, Rösener S. Elger M. Long term treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> renal disease progression. Kidney Int 1997; 51: 2–15<br />

<strong>of</strong> rats with FGF-2 results <strong>in</strong> focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.<br />

39. Hawk<strong>in</strong>s D, Cochran CG. Glomerular basement membrane<br />

Kidney Int 1995; 48: 1435–1440<br />

damage <strong>in</strong> immunological glomerulonephritis. Immunology 1968;<br />

33. Kriz W. et al. Frequent pathway to glomerulosclerosis. 14: 665–681<br />

Determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> tuft architecture. Podocyte damage <strong>and</strong> seg- 40. McCluskey RT. In: Hept<strong>in</strong>stall RH, ed. Pathology <strong>of</strong> the Kidney.<br />

mental sclerosis. Kidney Blood Press Res 1996; 19: 245–253 Little Brown, Boston, 1992; 169–260<br />

34. Hept<strong>in</strong>stall RH, ed. Pathology <strong>of</strong> the Kidney. 4th edn.Vol. 1. 41. Bohle A, Haussmann P, Vogt W. Über Beziehungen zwischen<br />

Little Brown, Boston, 1992; 647<br />

Lymphocyten und Harnkanälchenepithelien <strong>in</strong> der Niere des<br />

35. Müller CA, Markovic-Lipkovski J, Risler T, Bohle A, Müller Menschen. Kl<strong>in</strong> Wochenschr 1970; 48: 1323–1326