ExamView - CCE Practice Test - Williamson County Schools

ExamView - CCE Practice Test - Williamson County Schools

ExamView - CCE Practice Test - Williamson County Schools

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Name: ________________________ Class: ___________________ Date: __________<br />

ID: A<br />

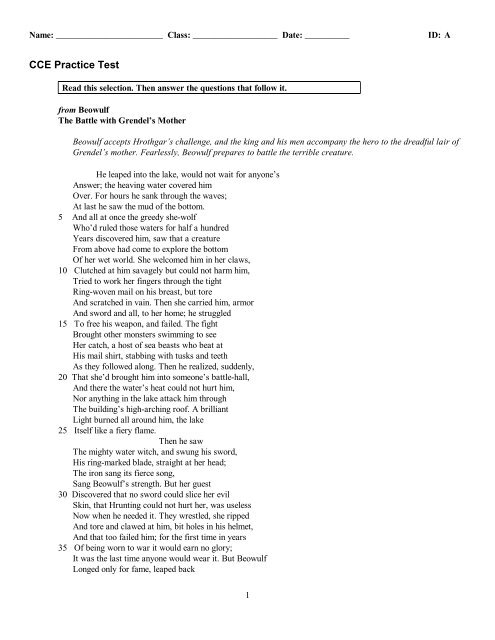

<strong>CCE</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Test</strong><br />

Read this selection. Then answer the questions that follow it.<br />

from Beowulf<br />

The Battle with Grendel’s Mother<br />

Beowulf accepts Hrothgar’s challenge, and the king and his men accompany the hero to the dreadful lair of<br />

Grendel’s mother. Fearlessly, Beowulf prepares to battle the terrible creature.<br />

He leaped into the lake, would not wait for anyone’s<br />

Answer; the heaving water covered him<br />

Over. For hours he sank through the waves;<br />

At last he saw the mud of the bottom.<br />

5 And all at once the greedy she-wolf<br />

Who’d ruled those waters for half a hundred<br />

Years discovered him, saw that a creature<br />

From above had come to explore the bottom<br />

Of her wet world. She welcomed him in her claws,<br />

10 Clutched at him savagely but could not harm him,<br />

Tried to work her fingers through the tight<br />

Ring-woven mail on his breast, but tore<br />

And scratched in vain. Then she carried him, armor<br />

And sword and all, to her home; he struggled<br />

15 To free his weapon, and failed. The fight<br />

Brought other monsters swimming to see<br />

Her catch, a host of sea beasts who beat at<br />

His mail shirt, stabbing with tusks and teeth<br />

As they followed along. Then he realized, suddenly,<br />

20 That she’d brought him into someone’s battle-hall,<br />

And there the water’s heat could not hurt him,<br />

Nor anything in the lake attack him through<br />

The building’s high-arching roof. A brilliant<br />

Light burned all around him, the lake<br />

25 Itself like a fiery flame.<br />

Then he saw<br />

The mighty water witch, and swung his sword,<br />

His ring-marked blade, straight at her head;<br />

The iron sang its fierce song,<br />

Sang Beowulf’s strength. But her guest<br />

30 Discovered that no sword could slice her evil<br />

Skin, that Hrunting could not hurt her, was useless<br />

Now when he needed it. They wrestled, she ripped<br />

And tore and clawed at him, bit holes in his helmet,<br />

And that too failed him; for the first time in years<br />

35 Of being worn to war it would earn no glory;<br />

It was the last time anyone would wear it. But Beowulf<br />

Longed only for fame, leaped back<br />

1

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Into battle. He tossed his sword aside,<br />

Angry; the steel-edged blade lay where<br />

40 He’d dropped it. If weapons were useless he’d use<br />

His hands, the strength in his fingers. So fame<br />

Comes to the men who mean to win it<br />

And care about nothing else! He raised<br />

His arms and seized her by the shoulder; anger<br />

45 Doubled his strength, he threw her to the floor.<br />

She fell, Grendel’s fierce mother, and the Geats’<br />

Proud prince was ready to leap on her. But she rose<br />

At once and repaid him with her clutching claws,<br />

Wildly tearing at him. He was weary, that best<br />

50 And strongest of soldiers; his feet stumbled<br />

And in an instant she had him down, held helpless.<br />

Squatting with her weight on his stomach, she drew<br />

A dagger, brown with dried blood, and prepared<br />

To avenge her only son. But he was stretched<br />

55 On his back, and her stabbing blade was blunted<br />

By the woven mail shirt he wore on his chest.<br />

The hammered links held; the point<br />

Could not touch him. He’d have traveled to the bottom of the earth,<br />

Edgetho’s son, and died there, if that shining<br />

60 Woven metal had not helped—and Holy<br />

God, who sent him victory, gave judgment<br />

For truth and right, Ruler of the Heavens,<br />

Once Beowulf was back on his feet and fighting.<br />

Then he saw, hanging on the wall, a heavy<br />

65 Sword, hammered by giants, strong<br />

And blessed with their magic, the best of all weapons<br />

But so massive that no ordinary man could lift<br />

Its carved and decorated length. He drew it<br />

From its scabbard, broke the chain on its hilt,<br />

70 And then, savage, now, angry<br />

And desperate, lifted it high over his head<br />

And struck with all the strength he had left,<br />

Caught her in the neck and cut it through,<br />

Broke bones and all. Her body fell<br />

75 To the floor, lifeless, the sword was wet<br />

With her blood, and Beowulf rejoiced at the sight.<br />

The brilliant light shone, suddenly,<br />

As though burning in that hall, and as bright as Heaven’s<br />

Own candle, lit in the sky. He looked<br />

80 At her home, then following along the wall<br />

Went walking, his hands tight on the sword,<br />

His heart still angry. He was hunting another<br />

Dead monster, and took his weapon with him<br />

For final revenge against Grendel’s vicious<br />

85 Attacks, his nighttime raids, over<br />

2

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

And over, coming to Herot when Hrothgar’s<br />

Men slept, killing them in their beds,<br />

Eating some on the spot, fifteen<br />

Or more, and running to his loathsome moor<br />

90 With another such sickening meal waiting<br />

In his pouch. But Beowulf repaid him for those visits,<br />

Found him lying dead in his corner,<br />

Armless, exactly as that fierce fighter<br />

Had sent him out from Herot, then struck off<br />

95 His head with a single swift blow. The body<br />

Jerked for the last time, then lay still.<br />

From Beowulf, translated by Burton Raffel. Translation copyright 1963 by Burton Raffel. Used by<br />

permission of Dutton Signet, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.<br />

READING COMPREHENSION<br />

____ 1. In lines 1–2, the author develops Beowulf’s character by —<br />

A. comparing him with other heroes<br />

B. describing the character’s actions<br />

C. showing other characters’ reactions<br />

D. describing his physical appearance<br />

____<br />

2. Which descriptive phrases characterize Grendel’s mother’s monstrous qualities?<br />

A. A creature from above and sea beasts<br />

B. The greedy she-wolf and the mighty water witch<br />

C. A fiery flame and Proud prince<br />

D. Strongest of soldiers and fierce fighter<br />

3

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

____<br />

3. In lines 36–38, the narrator’s comment that “Beowulf / Longed only for fame, leaped back / Into battle”<br />

characterizes Beowulf as —<br />

A. weakened<br />

B. intelligent<br />

C. conquered<br />

D. resolute<br />

____ 4. The conflict in lines 46–50 can best be described as —<br />

A. internal because Grendel’s mother feels guilty about inflicting violence on Beowulf<br />

B. external because Beowulf and Grendel’s mother are in an underwater environment<br />

C. internal because Beowulf feels upset about the men Grendel’s mother has killed<br />

D. external because Beowulf and Grendel’s mother engage in a physical struggle<br />

____ 5. The climax of the excerpt occurs when Beowulf —<br />

A. descends into the lair of Grendel’s mother<br />

B. sees the brilliant light fill the hall<br />

C. cuts off the head of Grendel’s mother<br />

D. searches for Grendel’s body<br />

____ 6. The author’s primary purpose for writing this epic was probably to –<br />

A. persuade people to read poetic works<br />

B. teach the importance of vengeance<br />

C. provide an accurate historical account<br />

D. present a struggle between good and evil<br />

4

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Read this selection. Then answer the questions that follow it.<br />

In the medieval church, a pardoner was a clergy member who had authority from the pope to grant<br />

indulgences—certificates of forgiveness—to people who showed great charity. In practice, however, many<br />

pardoners were unethical and sold their certificates to make money for the church or themselves.<br />

from The Canterbury Tales<br />

The Pardoner’s Prologue<br />

“My lords”, he said, “in churches where I preach<br />

I cultivate a haughty kind of speech<br />

And ring it out as roundly as a bell;<br />

I’ve got it all by heart, the tale I tell.<br />

5 I have a text, it always is the same<br />

And always has been, since I learnt the game.<br />

Old as the hills and fresher than the grass,<br />

Radix malorum est cupiditas. . . .<br />

“I preach, as you have heard me say before,<br />

10 And tell a hundred lying mockeries more.<br />

I take great pains, and stretching out my neck<br />

To east and west I crane about and peck<br />

Just like a pigeon sitting on a barn.<br />

My hands and tongue together spin the yarn<br />

15 And all my antics are a joy to see.<br />

The curse of avarice and cupidity<br />

Is all my sermon, for it frees the pelf.<br />

Out come the pence, and specially for myself,<br />

For my exclusive purpose is to win<br />

20 And not at all to castigate their sin.<br />

Once dead what matter how their souls may fare?<br />

They can go blackberrying, for all I care! . . .<br />

“And thus I preach against the very vice<br />

I make my living out of—avarice.<br />

25 And yet however guilty of that sin<br />

Myself, with others I have power to win<br />

Them from it, I can bring them to repent;<br />

But that is not my principal intent.<br />

Covetousness is both the root and stuff<br />

30 Of all I preach. That ought to be enough.<br />

“Well, then I give examples thick and fast<br />

From bygone times, old stories from the past.<br />

A yokel mind loves stories from of old,<br />

Being the kind it can repeat and hold.<br />

35 What! Do you think, as long as I can preach<br />

And get their silver for the things I teach,<br />

That I will live in poverty, from choice?<br />

That’s not the counsel of my inner voice!<br />

5

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

No! Let me preach and beg from kirk to kirk<br />

40 And never do an honest job of work,<br />

No, nor make baskets, like St. Paul, to gain<br />

A livelihood. I do not preach in vain.<br />

There’s no apostle I would counterfeit;<br />

I mean to have money, wool and cheese and wheat<br />

45 Though it were given me by the poorest lad<br />

Or poorest village widow, though she had<br />

A string of starving children, all agape.<br />

No, let me drink the liquor of the grape<br />

And keep a jolly wench in every town!<br />

50 “But listen, gentlemen; to bring things down<br />

To a conclusion, would you like a tale?<br />

Now as I’ve drunk a draft of corn-ripe ale,<br />

By God it stands to reason I can strike<br />

On some good story that you all will like.<br />

55 For though I am a wholly vicious man<br />

Don’t think I can’t tell moral tales. I can!<br />

Here’s one I often preach when out for winning. . . .”<br />

from The Pardoner’s Tale<br />

It’s of three rioters I have to tell<br />

Who, long before the morning service bell,<br />

Were sitting in a tavern for a drink.<br />

And as they sat, they heard the hand-bell clink<br />

5 Before a coffin going to the grave;<br />

One of them called the little tavern-knave<br />

And said “Go and find out at once—look spry!—<br />

Whose corpse is in that coffin passing by;<br />

And see you get the name correctly too.”<br />

10 “Sir”, said the boy, “no need, I promise you;<br />

Two hours before you came here I was told.<br />

He was a friend of yours in days of old,<br />

And suddenly, last night, the man was slain,<br />

Upon his bench, face up, dead drunk again.<br />

15 There came a privy thief, they call him Death,<br />

Who kills us all round here, and in a breath<br />

He speared him through the heart, he never stirred.<br />

And then Death went his way without a word.<br />

He’s killed a thousand in the present plague,<br />

20 And, sir, it doesn’t do to be too vague<br />

If you should meet him; you had best be wary.<br />

Be on your guard with such an adversary,<br />

Be primed to meet him everywhere you go,<br />

That’s what my mother said. It’s all I know.”<br />

25 The publican joined in with, “By St. Mary,<br />

What the child says is right; you’d best be wary,<br />

6

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

This very year he killed, in a large village<br />

A mile away, man, woman, serf at tillage,<br />

Page in the household, children—all there were.<br />

30 Yes, I imagine that he lives round there.<br />

It’s well to be prepared in these alarms,<br />

He might do you dishonor.” “Huh, God’s arms!”<br />

The rioter said, “Is he so fierce to meet?<br />

I’ll search for him, by Jesus, street by street.<br />

35 God’s blessed bones! I’ll register a vow!<br />

Here, chaps! The three of us together now,<br />

Hold up your hands, like me, and we’ll be brothers<br />

In this affair, and each defend the others,<br />

And we will kill this traitor Death, I say!<br />

40 Away with him as he has made away<br />

With all our friends. God’s dignity! Tonight!”<br />

They made their bargain, swore with appetite,<br />

These three, to live and die for one another<br />

As brother-born might swear to his born brother<br />

45 And up they started in their drunken rage<br />

And made towards this village which the page<br />

And publican had spoken of before.<br />

Many and grisly were the oaths they swore,<br />

Tearing Christ’s blessed body to a shred;<br />

50 “If we can only catch him, Death is dead!”<br />

When they had gone not fully half a mile,<br />

Just as they were about to cross a stile,<br />

They came upon a very poor old man<br />

Who humbly greeted them and thus began,<br />

55 “God look to you, my lords, and give you quiet!”<br />

To which the proudest of these men of riot<br />

Gave back the answer, “What, old fool? Give place!<br />

Why are you all wrapped up except your face?<br />

Why live so long? Isn’t it time to die?”<br />

60 The old, old fellow looked him in the eye<br />

And said, “Because I never yet have found,<br />

Though I have walked to India, searching round<br />

Village and city on my pilgrimage,<br />

One who would change his youth to have my age.<br />

65 And so my age is mine and must be still<br />

Upon me, for such time as God may will.<br />

“Not even Death, alas, will take my life;<br />

So, like a wretched prisoner at strife<br />

Within himself, I walk alone and wait<br />

70 About the earth, which is my mother’s gate,<br />

Knock-knocking with my staff from night to noon<br />

And crying, ‘Mother, open to me soon!<br />

Look at me, mother, won’t you let me in?<br />

See how I wither, flesh and blood and skin!<br />

7

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

75 Alas! When will these bones be laid to rest?<br />

Mother, I would exchange—for that were best—<br />

The wardrobe in my chamber, standing there<br />

So long, for yours! Aye, for a shirt of hair<br />

To wrap me in!’ She has refused her grace,<br />

80 Whence comes the pallor of my withered face.<br />

“But it dishonored you when you began<br />

To speak so roughly, sir, to an old man,<br />

Unless he had injured you in word or deed.<br />

It says in holy writ, as you may read,<br />

85 ‘Thou shalt rise up before the hoary head<br />

And honor it.’ And therefore be it said<br />

‘Do no more harm to an old man than you,<br />

Being now young, would have another do<br />

When you are old’—if you should live till then.<br />

90 And so may God be with you, gentlemen,<br />

For I must go whither I have to go.”<br />

“By God,” the gambler said, “you shan’t do so,<br />

You don’t get off so easy, by St. John!<br />

I heard you mention, just a moment gone,<br />

95 A certain traitor Death who singles out<br />

And kills the fine young fellows hereabouts.<br />

And you’re his spy, by God! You wait a bit.<br />

Say where he is or you shall pay for it,<br />

By God and by the Holy Sacrament!<br />

100 I say you’ve joined together by consent<br />

To kill us younger folk, you thieving swine!”<br />

“Well, sirs,” he said, “if it be your design<br />

To find out Death, turn up this crooked way<br />

Towards that grove, I left him there today<br />

105 Under a tree, and there you’ll find him waiting.<br />

He isn’t one to hide for all your prating.<br />

You see that oak? He won’t be far to find.<br />

And God protect you that redeemed mankind,<br />

Aye, and amend you!” Thus that ancient man.<br />

110 At once the three young rioters began<br />

To run, and reached the tree, and there they found<br />

A pile of golden florins on the ground,<br />

New-coined, eight bushels of them as they thought.<br />

No longer was it Death those fellows sought,<br />

115 For they were all so thrilled to see the sight,<br />

The florins were so beautiful and bright,<br />

That down they sat beside the precious pile.<br />

The wickedest spoke first after a while.<br />

“Brothers,” he said, “you listen to what I say.<br />

120 I’m pretty sharp although I joke away.<br />

It’s clear that Fortune has bestowed this treasure<br />

To let us live in jollity and pleasure.<br />

8

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Light come, light go! We’ll spend it as we ought.<br />

God’s precious dignity! Who would have thought<br />

125 This morning was to be our lucky day?”<br />

Reading Comprehension<br />

From The History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth, translated with an introduction<br />

by Lewis Thorpe (Penguin Classics, 1966). Translation copyright © Lewis Thorpe, 1966.<br />

Used by permission of Penguin Books Ltd.<br />

Use “The Pardoner’s Prologue” (pp. 178–179) to answer these questions.<br />

____<br />

7. Which sentence best describes the structure of “The Pardoner’s Prologue”?<br />

A. It is part of a larger narrative about pilgrims on a journey.<br />

B. A flashback occurs that interrupts “The Pardoner’s Prologue.”<br />

C. It is narrated by a second pilgrim who accompanies the Pardoner.<br />

D. The line and stanza structure is different from that of “The Pardoner’s Tale.”<br />

____ 8. Chaucer’s ironic depiction of the Pardoner in lines 23–28 stems from the contrast between the clergyman’s —<br />

A. duty and practice<br />

B. sermons and prayers<br />

C. preaching and duty<br />

D. guilt and repentance<br />

Use “The Pardoner’s Tale” (pp. 179–182) to answer these questions.<br />

____ 9. The “very poor old man” the rioters meet in line 53 is someone who —<br />

A. welcomes death to end a long life<br />

B. enjoys the blessings of old age<br />

C. sees greed as humanity’s downfall<br />

D. laughs at life as a cruel joke<br />

9

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

____ 10. In lines 87–89, the old man advises the rioters to —<br />

A. cease their verbal abuse and move along<br />

B. live long enough to grow old and wise<br />

C. treat him as they would want to be treated<br />

D. hurry on their way to catch Death<br />

10

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Read this selection. Then answer the questions that follow it.<br />

Geoffrey of Monmouth was born around 1100, likely in the southeast part of Wales. As a cleric in<br />

Oxford, Geoffrey often translated Welsh legends into Latin texts. Around 1136, Geoffrey worked on these<br />

translations and wanted to attract the notice of his superiors. Consequently, he collected local myth, legend,<br />

and lore—adding some embellishments of his own— into the Historia Regum Britanniae, or The History of<br />

the Kings of Britain. The History traces the history of Britain from approximately 1100 B.C. to A.D. 689.<br />

According to The History, Britain was founded around 1100 B.C. by Brutus, a warrior of Trojan<br />

descent. As Brutus led a band of Trojans around Europe and northern Africa gaining wealth through<br />

military victory, he came eventually to Gaul, a region now covered largely by France. Brutus and his men<br />

fought the Gauls, but defeat seemed imminent. Brutus chose to retreat, loading his ships with the riches he<br />

had gained. Soon, he and his men landed on the island that would become Britain.<br />

from The History of the Kings of Britain<br />

Geoffrey of Monmouth<br />

1 At this time the island of Britain was called Albion. It was uninhabited except for a few giants. It was,<br />

however, most attractive, because of the delightful situation of its various regions, its forests, and the great<br />

number of its rivers, which teemed with fish; and it filled Brutus and his comrades with a great desire to live<br />

there. When they had explored the different districts, they drove the giants whom they had discovered into the<br />

caves in the mountains. With the approval of their leader they divided the land among themselves. They began<br />

to cultivate the fields and to build houses, so that in a short time you would have thought that the land had<br />

always been inhabited.<br />

2 Brutus then called the island Britain from his own name, and his companions he called Britons. His<br />

intention was that his memory should be perpetuated by the derivation of the name. A little later the language of<br />

the people, which had up to then been known as Trojan or Crooked Greek, was called British, for the same<br />

reason.<br />

3 Corineus, however, following in this the example of his leader, called the region of the kingdom which<br />

had fallen to his share Cornwall, after the manner of his own name, and the people who lived there he called<br />

Cornishmen. Although he might have chosen his own estates before all the others who had come there, he<br />

preferred the region which is now called Cornwall, either for its being the cornu or horn of Britain, or through a<br />

corruption of his own name.<br />

4 Corineus experienced great pleasure from wrestling with the giants, of whom there<br />

were far more there than in any of the districts which had been distributed among his comrades. Among the<br />

others there was a particularly repulsive one, called Gogmagog, who was twelve feet tall. He was so strong<br />

that, once he had given it a shake, he could tear up an oak-tree as though it were a hazel wand. Once, when<br />

Brutus was celebrating a day dedicated to the gods in the port where he had landed, this creature, along with<br />

twenty other giants, attacked him and killed a great number of the Britons. However, the<br />

11

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Britons finally gathered together from round and about and overcame the giants and slew them all, except for<br />

Gogmagog. Brutus ordered that he alone should be kept alive, for he wanted to see a wrestling-match between<br />

this giant and Corineus, who enjoyed beyond all reason matching himself against such monsters. Corineus was<br />

delighted by this. He girded himself up, threw off his armour and challenged Gogmagog to a wrestling-match.<br />

The contest began. Corineus moved in, so did the giant; each of them caught the other in a hold by twining his<br />

arms round him, and the air vibrated with their panting breath. Gogmagog gripped Corineus with all his might<br />

and broke three of his ribs, two on the right side and one on the left. Corineus then summoned all his strength,<br />

for he was infuriated by what had happened. He heaved Gogmagog up on to his shoulders, and running as fast<br />

as he could under the weight, he hurried off to the nearby coast. He clambered up to the top of a mighty cliff,<br />

shook himself free and hurled this deadly monster, whom he was carrying on his shoulders, far out into the sea.<br />

The giant fell on to a sharp reef of rocks, where he was dashed into a thousand fragments and stained the<br />

waters with his blood. The place took its name from the fact that the giant was hurled down there and it is<br />

called Gogmagog’s Leap to this day.<br />

Reading Comprehension<br />

From The History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth, translated with an introduction<br />

by Lewis Thorpe (Penguin Classics, 1966). Translation copyright © Lewis Thorpe, 1966.<br />

Used by permission of Penguin Books Ltd.<br />

____ 11. Why is the first paragraph characteristic of historical writing?<br />

A. The author describes only historically accurate events.<br />

B. The author reveals his personal interpretation.<br />

C. The author describes events in chronological order.<br />

D. The author acknowledges the existence of giants.<br />

____ 12. Based on the excerpt, the reader can infer that wrestling was —<br />

A. valued as a noble sport<br />

B. feared by most citizens<br />

C. considered a luxury<br />

D. watched only by royalty<br />

12

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

____ 13. In the last lines of the excerpt, the author’s purpose is to —<br />

A. stress the lasting importance of Gogmagog’s death<br />

B. connect a piece of ancient history with modern Britain<br />

C. explain the significance of a human’s defeating a giant<br />

D. persuade readers to visit Gogmagog’s Leap in Britain<br />

Use context clues and the Latin word and root definitions to answer the<br />

following questions.<br />

____ 14. The Latin root rupt means “to break.” What does the word corruption mean in line 18 of The History of the<br />

Kings of Britain?<br />

A. Complete and total destruction<br />

B. The gradual decaying or rotting of<br />

C. Moral depravity or dishonesty<br />

D. A change in the original form of<br />

____ 15. The Latin root vers means “turn.” What does the word adversary mean in line 79 of “The Pardoner’s<br />

Prologue”?<br />

A. Opponent<br />

B. Scoundrel<br />

C. Menace<br />

D. Trickster<br />

13

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Use context clues and your knowledge of roots and affixes to answer the following<br />

questions.<br />

____ 16. What does the word uninhabited mean in line 1 of The History of the Kings of Britain?<br />

A. Naturally beautiful<br />

B. Free of occupants<br />

C. Recently discovered<br />

D. Without reservation<br />

Use context clues and your knowledge of etymology to answer the following questions about<br />

words from "The Pardoner's Prologue."<br />

____ 17. Which word comes from haut or halt, an Old French word that means “high?”<br />

A. Huge<br />

B. Heart<br />

C. Haughty<br />

D. Hand<br />

14

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Revising and Editing<br />

Directions<br />

Read the expository essay and answer the questions that follow.<br />

(1) Relationships are an almost universal topic of interest. (2) People make art<br />

in order to explore the nature of relationships. (3) The ballads of medieval<br />

England and Scotland are one such art form. (4) Although written several<br />

hundred years ago, these songs are still well known today. (5) “Barbara Allan”<br />

and “Get Up and Bar the Door” both use the ballad form to relate different types<br />

of relationships involving strong women. (6) Although similar in structure, these<br />

two ballads portray two different relationships.<br />

(7) “Barbara Allan” tells of Sir John Graeme, who fell in love with Barbara<br />

Allan. (8) He summons a friend to bring her to him. (9) He is dying of heartache.<br />

(10) But when Barbara Allan arrives, she refuses Graeme’s love because he failed<br />

to toast her in public. (11) After she stubbornly refuses him in line 15, John<br />

Graeme dies. (12) As Barbara Allan leaves, she says that Graeme was her love<br />

and that “Since my love died for me today, I’ll die for him tomorrow.” (13) The<br />

poem tells the story of one love affair that ends sadly.<br />

(14) “Get Up and Bar the Door” is about another relationship. (15) This ballad<br />

uses humor to tell a story of stubbornness. (16) When the mistress of the<br />

household has work to do, her husband tells her close the door. (17) She replies<br />

that she will not do so in a hundred years. (18) The couple then agrees that<br />

whoever speaks first must fasten the door.<br />

(19) Later, two intruders enter the house, and because the couple refuses to<br />

talk, the strangers eat their food. (20) They also threaten to kiss the wife and<br />

shave the husband’s beard. (21) Until this point, the husband and wife are still too<br />

stubborn to speak. (22) The intruders threaten to scald the old man with super hot<br />

broth. (23) Then the man speaks out angrily. (24) His wife, however, rejoices<br />

saying, “Goodman, you’ve spoken the foremost word, / Get up and bar the door”.<br />

(25) She gleefully skips three times and gloats that now her husband must bar the<br />

door. (26) While “Barbara Allan” uses the ballad form to tell a romantic story,<br />

“Get Up and Bar the Door” employs humor to highlight the events of its<br />

narrative.<br />

(27) In the end, Barbara Allan regrets her stubbornness. (28) Both ballads<br />

relate a single incident. (29) Both ballads relate stories about headstrong women<br />

who refuse to make decisions in order to please someone else. (30) The wife in<br />

“Get Up and Bar the Door,” however, disregards the dangers presented by the<br />

intruders and simply revels in the fact that she has won the wager.<br />

____ 18. The thesis is effective because it —<br />

15

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

A. suggests a cause-and-effect relationship between the poems<br />

B. explains the historical significance of various art forms<br />

C. establishes the focus of the essay<br />

D. summarizes the writer’s opinions about poetry<br />

____ 19. What is the best way to combine sentences 8 and 9 using a subordinate clause and an independent clause?<br />

A. He summons a friend to bring her to him, and he is dying of heartache.<br />

B. Because he is dying of heartache, he summons a friend to bring her to him.<br />

C. He is dying of heartache, and he summons a friend to bring her to him.<br />

D. He summons a friend to bring her to him who is dying of heartache.<br />

____ 20. Which sentence gives a specific example that supports the thesis?<br />

A. Sentence 7<br />

B. Sentence 8<br />

C. Sentence 13<br />

D. Sentence 14<br />

____ 21. For the essay to follow proper organization, sentence 27 should follow —<br />

A. Sentence 25<br />

B. Sentence 28<br />

C. Sentence 29<br />

D. Sentence 30<br />

16

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Use “Sonnet 61” (p. 197) to answer these questions.<br />

____ 22. Based on the first quatrain, the reader can conclude that the speaker’s relationship with the subject of the poem<br />

is —<br />

A. coming to an end<br />

B. becoming difficult<br />

C. growing deeper<br />

D. resulting in marriage<br />

____ 23. The sonnet’s turn, or shift in thought, reveals that the speaker feels —<br />

A. bitter about the end of the relationship with the poem’s subject<br />

B. sorry that he never loved the poem’s subject<br />

C. hopeful that the poem’s subject still loves him<br />

D. confident that he no longer loves the poem’s subject<br />

____ 24. Which words from the poem best demonstrate exact rhyme?<br />

A. me, free (lines 2 and 4)<br />

B. again, retain (lines 6 and 8)<br />

C. failing, kneeling (lines 10 and 11)<br />

D. over, recover (lines 13 and 14)<br />

17

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Read this selection. Then answer the questions that follow it.<br />

from A Man and His Pig<br />

Lewis Lapham<br />

1 Toward the end of last month I received an urgent telephone call from a correspondent on the frontiers of<br />

the higher technology who said that I had better begin thinking about pigs. Soon, he said, it would be<br />

possible to grow a pig replicating the DNA of anybody rich enough to order such a pig, and once the<br />

technique was safely in place, I could forget most of what I had learned about the consolations of literature<br />

and philosophy. He didn’t yet have the details of all the relevant genetic engineering, and he didn’t expect<br />

custom-tailored pigs to appear in time for the Neiman-Marcus Christmas catalogue, but the new day was<br />

dawning a lot sooner than most people supposed, and he wanted to be sure that I was conversant with the<br />

latest trends.<br />

2 At first I didn’t appreciate the significance of the news, and I said something polite about the wonders<br />

that never cease. With the air of impatience characteristic of him when speaking to the literary sector, my<br />

correspondent explained that very private pigs would serve as banks, or stores, for organ transplants. If the<br />

owner of a pig had a sudden need for a heart or a kidney, he wouldn’t have to buy the item on the spot<br />

market. Nor would he have to worry about the availability, location, species, or racial composition of a<br />

prospective donor. He merely would bring his own pig to the hospital, and the surgeons would perform the<br />

metamorphosis.<br />

3 “Think of pigs as wine cellars,” the correspondent said, “and maybe you will understand their place in<br />

the new scheme of things.”<br />

4 He was in a hurry, and he hung up before I had the chance to ask further questions, but after brooding on<br />

the matter for some hours I thought that I could grasp at least a few of the preliminary implications.<br />

Certainly the manufacture of handmade pigs was consistent with the spirit of an age devoted to the beauty<br />

of money. For the kind of people who already own most everything worth owning—for President Reagan’s<br />

friends in Beverly Hills and the newly minted plutocracy that glitters in the show windows of the national<br />

media—what toy or bauble could match the priceless objet d’art of a surrogate self?<br />

5 My correspondent didn’t mention a probable price for a pig made in one’s own image, but I’m sure that<br />

it wouldn’t come cheap. The possession of such a pig obviously would become a status symbol of the first<br />

rank, and I expect that the animals sold to the carriage trade would cost at least as much as a Rolls-Royce<br />

or beachfront property in Malibu. Anybody wishing to present an affluent countenance to the world would<br />

be obliged to buy a pig for every member of the household—for the servants and secretaries as well as for<br />

the children. Some people would keep a pig at both their town and country residences, and celebrities as<br />

precious as Joan Collins or as nervous as General Alexander Haig might keep herds of twenty to thirty<br />

pigs. The larger corporations might offer custom-made pigs—together with the limousines, the stock<br />

options, and the club memberships—as another perquisite to secure the loyalty of the executive classes.<br />

6 Contrary to the common belief, pigs are remarkably clean and orderly animals. They could be trained to<br />

behave graciously in the nation’s better restaurants, thus accustoming themselves to a taste not only for<br />

truffles but also for Dom Pérignon and béchamel sauce. If a man needs a new stomach in a hurry, it’s<br />

helpful if the stomach in transit already knows what’s what.<br />

7 Within a matter of a few months (i.e., once people began to acquire more respectful attitudes toward<br />

pigs), I assume that designers like Galanos and Giorgio Armani would introduce lines of porcine couture.<br />

On the East Side of Manhattan, as well as in the finer suburbs, I can imagine gentlemen farmers opening<br />

schools for pigs. Not a rigorous curriculum, of course, nothing as elaborate as the dressage taught to<br />

thoroughbred horses, but a few airs and graces, some tips on good grooming, and a few phrases of<br />

rudimentary French.<br />

18

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

8 As pigs became more familiar as companions to the rich and famous, they might begin to attend charity<br />

balls and theater benefits. I can envision collections of well-known people posing with their pigs for<br />

photographs in the fashion magazines—Katharine Graham and her pig at Nantucket, Donald Trump and<br />

his pig at Palm Beach, Norman Mailer and his pig pondering a metaphor in the writer’s study.<br />

9 Celebrities too busy to attend all the occasions to which they’re invited might choose to send their pigs.<br />

The substitution could not be construed as an insult, because the pigs—being extraordinarily expensive and<br />

well dressed—could be seen as ornamental figures of stature (and sometimes subtlety of mind) equivalent<br />

to that of their patrons. Senators could send their pigs to routine committee meetings, and President Reagan<br />

might send one or more of his pigs to state funerals in lieu of Vice President Bush.<br />

10 People constantly worrying about medical emergencies probably wouldn’t want to leave home without<br />

their pigs. Individuals suffering only mild degrees of stress might get in the habit of leading their pigs<br />

around on leashes, as if they were poodles or Yorkshire terriers. People displaying advanced symptoms of<br />

anxiety might choose to sit for hours on a sofa or park bench, clutching their pigs as if they were the best of<br />

all possible teddy bears, content to look upon the world with the beatific smile of people who know they<br />

have been saved.<br />

11 I’m sure the airlines would allow first-class passengers to travel to Europe or California in the company<br />

of their pigs, and I like to imagine the sight of the pairs of differently shaped heads when seen from the rear<br />

of the cabin.<br />

12 For people living in Dallas or Los Angeles, it probably wouldn’t be too hard to make space for a pig in<br />

a backyard or garage; in Long Island and Connecticut, the gentry presumably would keep herds of pigs on<br />

their estates, and this would tend to sponsor the revival of the picturesque forms of environmentalism<br />

favored by Marie Antoinette and the Sierra Club. The nation’s leading architects, among them Philip<br />

Johnson and I.M. Pei, could be commissioned to design fanciful pigpens distinguished by postmodern<br />

allusions to nineteenth-century barnyards.<br />

13 But in New York, the keeping of swine would be a more difficult business, and so I expect that the<br />

owners of expensive apartments would pay a good deal more attention to the hiring of a swineherd than to<br />

the hiring of a doorman or managing agent. Pens could be constructed in the basement, but somebody<br />

would have to see to it that the pigs were comfortable, well fed, and safe from disease. The jewelers in town<br />

could be relied upon to devise name tags, in gold or lapis lazuli, that would prevent the appalling possibility<br />

of mistaken identity. If a resident grandee had to be rushed to the hospital in the middle of the night, and if<br />

it so happened that the heart of one of Dan Rather’s pigs was placed in the body of Howard Cosell, I’m<br />

afraid that even Raoul Felder would be hard pressed to work out an equitable settlement.<br />

14 With regard to the negative effects of the new technology, I could think of relatively few obvious losses.<br />

The dealers in bacon and pork sausage might suffer a decline in sales, and footballs would have to be made<br />

of something other than pigskin. The technology couldn’t be exported to Muslim countries, and certain<br />

unscrupulous butchers trading in specialty meats might have to be restrained from buying up the herds<br />

originally collected by celebrities recently deceased. Without strict dietary laws I can imagine impresarios<br />

of a nouvelle cuisine charging $2,000 for choucroute de Barbara Walters or potted McEnroe.<br />

15 But mostly I could think only of the benign genius of modern science. Traffic in the cities could be<br />

expected to move more gently (in deference to the number of pigs roaming the streets for their afternoon<br />

stroll), and I assume that the municipal authorities would provide large meadows for people wishing to<br />

romp and play with their pigs.<br />

From “A Man and His Pig,” from 30 Satires by Lewis Lapham. Copyright © 2003 by Lewis H. Lapham. Used<br />

by permission of The New Press.<br />

Reading Comprehension<br />

19

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

____ 25. Which statement best summarizes the correspondent’s explanation in paragraph 2?<br />

A. The pigs would be a lucrative and desirable investment for the very wealthy.<br />

B. Pigs would be genetically designed to serve as surrogate children for celebrities.<br />

C. The pigs would be bought, sold, and stored by the wealthy in cellars, like wine.<br />

D. Pigs with the same DNA as their owners would provide organs for transplants.<br />

20

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Read this selection. Then answer the questions that follow it.<br />

Welcome to the Library . . . Now Leave!<br />

1 Public librarians around the country dread the mid-afternoon hours. They know that around 3:00 P.M.<br />

every weekday, hordes of hungry, noisy, and rowdy teenagers are leaving school and, having no better<br />

place to go, heading to public libraries to “do their homework.” That’s the official reason, but as most<br />

librarians know, the more likely scenario is that the teens will invade and conquer. They will swarm the<br />

tables, chairs, and computer stations, gossiping noisily, making cell phone calls, and eating messy snacks.<br />

They will chase one another around the stacks and cause a commotion, raising complaints and ruining the<br />

quiet atmosphere so conducive to studying.<br />

2 In many public libraries around the country, incidents of fights, vandalism, and even criminal behavior<br />

have forced library boards to take drastic action. For example, in one Illinois community, the library<br />

requires all children under age 16 to be accompanied by an adult. In Joliet, Illinois, all teens have to sign in<br />

and show identification in order to use the library. Those without ID must sit and wait while a librarian<br />

calls their parents.<br />

3 The problem of rowdy teens hanging out in libraries is not limited to Illinois; librarians everywhere deal<br />

with the same issue. But kicking teens out, treating them like felons, or calling the police are not good<br />

solutions. Discrimination against teens in public libraries is not only unfair to young people; it also betrays<br />

the mission statement of nearly every public library in America. What’s more, pushing teens away from<br />

libraries is a shortsighted response that misses an ideal opportunity for community building and leads teens<br />

to perceive the library as a negative, exclusionary place. Why risk all of this when libraries could gain so<br />

much by welcoming local teens?<br />

4 Teen advocates and civil rights experts are quick to respond to some public libraries’ decisions to ban<br />

teens or restrict their access to library materials. To them, the matter is one of clear-cut discrimination.<br />

When a library policy appears to “rule out or identify for different treatment a particular group of people,”<br />

librarian Leslie Edmonds Holt is quick to classify the problem as a civil rights issue. Genevieve Gallagher,<br />

a librarian from Orange <strong>County</strong>, Virginia, puts the issue more bluntly, identifying the restrictive library<br />

policies in Joliet in particular as “blatant discrimination that would be unthinkable if the group in question<br />

was anyone other than teens.”<br />

5 As a result, librarians, who are usually great advocates of freedom of speech, suddenly find themselves<br />

putting the brakes on young people’s intellectual freedom. Restricting access to libraries goes against<br />

everything in which librarians—public or otherwise—believe. Louise McAulay, the executive director of<br />

the Suburban Library System in Illinois, says that the idea of denying teens access “doesn’t seem consistent<br />

with normal library policies.” Authors Susan B. Harden and Melanie Huggins remind librarians that<br />

dealing with whoever walks in the door is an occupational challenge: “Simply put, any barrier to library<br />

access is a failure on the part of libraries to serve this group. Libraries exist to serve everyone and can play<br />

a positive role in the lives of teens—even difficult ones.” To turn a young adult away from the library is<br />

simply not an acceptable option.<br />

6 Turning teens away or otherwise limiting their access to libraries is not only an issue of<br />

discrimination—it is also an issue of safety. Sadly, public libraries have become de facto teen day-care<br />

centers for many American students. According to one study, roughly seven million high school students<br />

are left to their own devices after school. Without extracurricular activities or parental supervision, many<br />

of these teens have no place to go aside from the library. While many do homework or study, some students<br />

are just looking for a safe place to hang out. Banishing students from the library or otherwise restricting<br />

their access puts some of these teens at risk. Is that a fair trade-off?<br />

21

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

7 Although some critics argue that public libraries are not responsible for teens’ safety, many librarians<br />

disagree. Evan St. Lifer points out that children’s well-being has been one of the bedrock principles of<br />

public libraries since the mid-nineteenth century. The earliest public libraries specifically identified saving<br />

“youth from the evils of an ill-spent leisure” as one of their many goals. St. Lifer poses the question, Is it<br />

the mission of the public library to “make the community better?” His answer is yes. Looking at the current<br />

mission statements of public libraries around the nation, he discovers that most still include the concept of<br />

enhancing community life, which means providing a safe haven for every member—including teenagers.<br />

According to writer Patrick Jones, “The role of any library is to make its community better, so the role of<br />

librarians working with teens is to make that community better.”<br />

8 Jami Jones takes a positive approach to the problem of teens and libraries. She applies the concept of<br />

“social capital,” a term that sociologists use to describe what Jones calls “the glue that holds us together.”<br />

In other words, librarians and libraries are part of a complex web. Rather than thinking of themselves as<br />

babysitters or traffic police, librarians should see themselves and behave like society’s “glue.” As role<br />

models and authority figures, they can understand teens’ needs and involve young people in the library<br />

community. They can, as Jones puts it, “help shape the way children develop, view others in their<br />

community, and relate to institutions.” Librarians have a responsibility to keep teens safe, absorb them into<br />

the larger community, and teach them to value books and to respect others.<br />

9 Many librarians might be surprised to learn how relatively easy it can be to help teens settle down and<br />

get involved. In her article “Looks Like Teen Spirit,” Kimberly Bolan describes the success many libraries<br />

have had in creating study areas and lounges that specifically meet the needs of teenagers. As she explains,<br />

“many libraries have transformed their young adult areas into more efficient, innovative, and inspirational<br />

spaces.” By creating open, flexibly designed spaces that are set apart from the other patrons, libraries can<br />

appeal to teens and provide them with a relaxed atmosphere to read, study, socialize, and even eat. Some<br />

may argue that catering to teens’ penchants for gossip and pizza is hardly a library’s responsibility.<br />

Perhaps the question of why a community would model a library after a living room can be best answered<br />

with another question: Why not make young people feel at home? A comfortable environment will only<br />

increase the likelihood that a young person will discover the joys of reading and of visiting the library<br />

10 What critics of this solution often forget is that every age group deserves equal access to libraries.<br />

Teens are often unfairly singled out because of their behavior. But as Susan B. Harden and Melanie<br />

Huggins point out in their article “Here Comes Trouble,” teens are not the only ones who make noise.<br />

“Younger kids scream, laugh, and squeal with excitement,” they say. “At the same time, seniors with<br />

hearing aids can get loud, and babies, by nature, are pretty noisy folks.” To single out teens is unfair, and<br />

such treatment is unlikely to build their trust in or respect for authority. Harden and Huggins’ suggestions<br />

for finding fair ways to make libraries accessible and comfortable for all patrons include having simple,<br />

clear rules that are applied consistently to all library users. They also encourage librarians to treat each<br />

subset of patrons with respect and understanding. Harden and Huggins comment that librarians should be<br />

more sympathetic to common teen behavior: “Socializing in large groups, boisterous banter, pushing<br />

boundaries, and inappropriate use of library computers or furniture are easier to digest when we understand<br />

the physical, emotional, and intellectual development of teens.” Harden and Huggins also recommend that<br />

librarians think back to their own teenage years before dealing harshly with adolescent patrons.<br />

11 Today’s teenagers will soon grow up and graduate high school, but another wave is coming right on<br />

their heels. Like it or not, there will always be teenagers around, working on research papers or looking for<br />

good books to read. We need to consider the importance of building relationships with these teens.<br />

Librarians and library board members who take the time to understand and accommodate the needs of teens<br />

will find reward in having created a welcoming space that serves the entire community. We should all take<br />

a page from that book.<br />

Reading Comprehension<br />

22

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

____ 26. Based on paragraph 1, the reader can conclude that —<br />

A. teenagers endanger regular public library patrons<br />

B. libraries are not appropriate places for teenagers<br />

C. teenagers often behave inappropriately in libraries<br />

D. librarians must provide teenagers with a safe place<br />

____ 27. What is the author’s main claim?<br />

A. Keeping teens out of libraries stops them from becoming members of the community.<br />

B. Pushing teens out of libraries is unfair and against the basic mission of libraries.<br />

C. Denying teens access to libraries will make them dislike books.<br />

D. Kicking teens out of libraries denies them an opportunity to gain a solid education.<br />

____ 28. What is the author’s opinion about the practice of banning teens from libraries?<br />

A. Teens should be banned only for noisy and disruptive behavior.<br />

B. It is a poor solution that runs the risk of alienating teens.<br />

C. Banning teens is one of the few options that libraries have.<br />

D. It is a solution that would punish other library patrons.<br />

23

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Vocabulary<br />

Use context clues and your knowledge of connotation and denotation to answer the<br />

following questions.<br />

____ 29. What connotation does the word beatific have in paragraph 10 of “A Man and His Pig”?<br />

A. Satisfied<br />

B. Smug<br />

C. Enlightened<br />

D. Happy<br />

Use context clues to answer the following questions about words in “A Man and His Pig.”<br />

____ 30. What does the word implications mean in paragraph 4?<br />

A. Implied meanings or significance<br />

B. Potential opposing arguments<br />

C. Unusual comparisons or descriptions<br />

D. Straightforward statistics<br />

____ 31. What does the word plutocracy mean in paragraph 4?<br />

A. Close friend of a famous person<br />

B. Professional shopper<br />

C. Wealthy governing class<br />

D. Bright and shiny new object<br />

24

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Use context clues and your knowledge of roots and affixes to answer the following<br />

questions.<br />

____ 32. What does the word rudimentary mean in paragraph 7 of “A Man and His Pig”?<br />

A. Primary<br />

B. Basic<br />

C. Principled<br />

D. Daily<br />

25

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Revising and Editing<br />

Directions<br />

Read the persuasive essay and answer the questions that follow.<br />

(1) It’s 7:45 in the evening, and you’re still trying to finish your homework.<br />

(2) You’re exhausted. (3) You’re frustrated. (4) You can’t believe you’ve been doing<br />

homework since you arrived home four hours earlier. (5) This situation might sound familiar to<br />

you. (6) Many students are overwhelmed by too much homework. (7) To remedy this problem<br />

schools should implement plans that restrict the amount of homework students have each week.<br />

(8) The first reason that schools should implement homework plans is that large quantities<br />

of homework often result in poor quality. (9) Students works quickly in order to finish the<br />

mounds of homework assigned to them. (10) A student would spend more time on homework if<br />

he or she had only two assignments to complete instead of four. (11) Fewer assignments would<br />

benefit both students and teachers. (12) Students would have more time to focus their efforts.<br />

(13) In addition teachers would have a better understanding of how students are doing in their<br />

classes.<br />

(14) Another reason for limiting homework is that many students participate in<br />

extracurricular activities or hold after-school jobs. (15) These activities benefit students. (16)<br />

These activities limit the amount of available homework time. (17) A plan that limited<br />

homework each night would allow ample time for activities, jobs, and schoolwork.<br />

(18) Another reason for instituting homework plans is that students would be able to spend<br />

more time with their families. (19) Hours and hours of homework prevent students from<br />

spending quality time with their parents, guardians, and siblings. (20) Less homework would<br />

increase family communication. (21) Less homework would provide more bonding time at<br />

home.<br />

(22) It is rare for a student to have less than two hours of homework each night. (23) As a<br />

result student free time has never been so low. (24) Homework schedules are necessary to give<br />

students the time they need to produce quality work, to participate in activities and jobs, and to<br />

spend more time with their families. (25) <strong>Schools</strong> need to recognize this growing problem before<br />

student learning and growth is permanently damaged.<br />

____ 33. Choose the best way to vary the beginnings of sentences 15 and 16.<br />

A. The activities benefit students. The activities limit the amount of available homework time.<br />

B. Activities benefit students. Activities, however, limit the amount of available homework<br />

time.<br />

C. Students benefit from these activities. Students have limited available homework time.<br />

D. These activities benefit students. However, they also limit the amount of available<br />

homework time.<br />

26

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

____ 34. Which word in sentence 25 is an example of persuasive language?<br />

A. <strong>Schools</strong><br />

B. This<br />

C. Is<br />

D. Damaged<br />

27

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Read the poem. Then answer the questions that follow it.<br />

The Question<br />

Percy Bysshe Shelley<br />

I<br />

II<br />

III<br />

I dreamed that, as I wandered by the way,<br />

Bare Winter suddenly was changed to Spring,<br />

And gentle odours led my steps astray,<br />

Mixed with a sound of waters murmuring<br />

5 Along a shelving bank of turf, which lay<br />

Under a copse, and hardly dared to fling<br />

Its green arms round the bosom of the stream,<br />

But kissed it and then fled, as thou mightest in dream.<br />

There grew pied wind-flowers and violets,<br />

10 Daisies, those pearled Arcturi of the earth,<br />

The constellated flower that never sets;<br />

Faint oxslips; tender bluebells, at whose birth<br />

The sod scarce heaved; and that tall flower that wets—<br />

Like a child, half in tenderness and mirth—<br />

15 Its mother’s face with Heaven’s collected tears,<br />

When the low wind, its playmate’s voice, it hears.<br />

And in the warm hedge grew lush eglantine,<br />

Green cowbind and the moonlight-coloured may,<br />

And cherry-blossoms, and white cups, whose wine<br />

20 Was the bright dew, yet drained not by the day;<br />

And wild roses, and ivy serpentine,<br />

With its dark buds and leaves, wandering astray;<br />

And flowers azure, black, and streaked with gold,<br />

Fairer than any wakened eyes behold.<br />

IV<br />

25 And nearer to the river’s trembling edge<br />

There grew broad flag-flowers, purple pranked with white,<br />

And starry river buds among the sedge,<br />

And floating water-lilies, broad and bright,<br />

Which lit the oak that overhung the hedge<br />

30 With moonlight beams of their own watery light;<br />

And bulrushes, and reeds of such deep green<br />

As soothed the dazzled eye with sober sheen.<br />

28

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

V<br />

Methought that of these visionary flowers<br />

I made a nosegay, bound in such a way<br />

35 That the same hues, which in their natural bowers<br />

Were mingled or opposed, the like array<br />

Kept these imprisoned children of the Hours<br />

Within my hand,—and then, elate and gay,<br />

I hastened to the spot whence I had come.<br />

40 That I might present it! — Oh! To whom?<br />

Reading Comprehension<br />

____ 35. The phrase “waters murmuring” in line 4 appeals to the sense of —<br />

A. sight<br />

B. smell<br />

C. hearing<br />

D. touch<br />

____ 36. The phrase “green arms” in line 7 demonstrates Shelley’s personification of —<br />

A. gentle odors<br />

B. a bank of turf<br />

C. spring<br />

D. a copse<br />

____ 37. Which statement best describes the theme of the poem?<br />

A. You can find great happiness in nature.<br />

B. Flowers are the perfect gift for anyone.<br />

C. You should always have a goal in mind.<br />

D. Dreams usually result in disappointment.<br />

29

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

____ 38. Which emotion does the speaker express in the last stanza?<br />

A. Fear of imprisonment<br />

B. Boredom with winter<br />

C. Desire to regain control<br />

D. Delight with nature<br />

30

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Read this selection. Then answer the questions that follow it.<br />

The Mouse<br />

Saki<br />

1 Theodoric Voler had been brought up, from infancy to the confines of middle age, by a fond mother whose<br />

chief solicitude had been to keep him screened from what she called the coarser realities of life. When she died<br />

she left Theodoric alone in a world that was as real as ever, and a good deal coarser than he considered it had<br />

any need to be. To a man of his temperament and upbringing even a simple railway journey was crammed with<br />

petty annoyances and minor discords, and as he settled himself down in a second-class compartment one<br />

September morning he was conscious of ruffled feelings and general mental discomposure. He had been staying<br />

at a country vicarage, the inmates of which had been certainly neither brutal nor bacchanalian, but their<br />

supervision of the domestic establishment had been of the lax order which invites disaster. The pony carriage<br />

that was to take him to the station had never been properly ordered, and when the moment for his departure<br />

drew near the handyman who should have produced the required article was nowhere to be found. In this<br />

emergency Theodoric, to his mute but very intense disgust, found himself obliged to collaborate with the vicar’s<br />

daughter in the task of harnessing the pony, which necessitated groping about in an ill-lighted outhouse called a<br />

stable, and smelling very like one—except in patches where it smelt of mice. Without being actually afraid of<br />

mice, Theodoric classed them among the coarser incidents of life, and considered that Providence, with a little<br />

exercise of moral courage, might long ago have recognized that they were not indispensable, and have<br />

withdrawn them from circulation. As the train glided out of the station Theodoric’s nervous imagination<br />

accused himself of exhaling a weak odor of stableyard, and possibly of displaying a moldy straw or two on his<br />

usually well-brushed garments. Fortunately the only other occupant of the compartment, a lady of about the<br />

same age as himself, seemed inclined for slumber rather than scrutiny; the train was not due to stop till the<br />

terminus was reached, in about an hour’s time, and the carriage was of the old-fashioned sort, that held no<br />

communication with a corridor, therefore no further traveling companions were likely to intrude on Theodoric’s<br />

semi-privacy. And yet the train had scarcely attained its normal speed before he became reluctantly but vividly<br />

aware that he was not alone with the slumbering lady; he was not even alone in his own clothes. A warm,<br />

creeping movement over his flesh betrayed the unwelcome and highly resented presence, unseen but poignant,<br />

of a strayed mouse, that had evidently dashed into its present retreat during the episode of the pony harnessing.<br />

Furtive stamps and shakes and wildly directed pinches failed to dislodge the intruder, whose motto, indeed,<br />

seemed to be Excelsior; and the lawful occupant of the clothes lay back against the cushions and endeavored<br />

rapidly to evolve some means for putting an end to the dual ownership. It was unthinkable that he should<br />

continue for the space of a whole hour in the horrible position of a Rowton House for vagrant mice (already his<br />

imagination had at least doubled the numbers of the alien invasion). On the other hand, nothing less drastic than<br />

partial disrobing would ease him of his tormentor, and to undress in the presence of a lady, even for so laudable<br />

a purpose, was an idea that made his eartips tingle in a blush of abject shame. He had never been able to bring<br />

himself even to the mild exposure of open-work socks in the presence of the fair sex. And yet—the lady in this<br />

case was to all appearances soundly and securely asleep; the mouse, on the other hand, seemed to be trying to<br />

crowd a Wanderjahr into a few strenuous minutes. If there is any truth in the theory of transmigration, this<br />

particular mouse must certainly have been in a former state a member of the Alpine Club. Sometimes in its<br />

eagerness it lost its footing and slipped for half an inch or so; and then, in fright, or more probably temper, it<br />

bit. Theodoric was goaded into the most audacious undertaking of his life. Crimsoning to the hue of a beetroot<br />

and keeping an agonized watch on his slumbering fellow-traveler, he swiftly and noiselessly secured the ends of<br />

his railway-rug to the racks on either side of the carriage, so that a substantial curtain hung athwart the<br />

compartment. In the narrow dressing-room that he had thus improvised he proceeded with violent haste to<br />

extricate himself partially and the mouse entirely from the surrounding casings of tweed and half-wool.<br />

31

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

As the unraveled mouse gave a wild leap to the floor, the rug, slipping its fastening at either end, also came<br />

down with a heart-curdling flop, and almost simultaneously the awakened sleeper opened her eyes. With a<br />

movement almost quicker than the mouse’s, Theodoric pounced on the rug, and hauled its ample folds chin-high<br />

over his dismantled person as he collapsed into the further corner of the carriage. The blood raced and beat in<br />

the veins of his neck and forehead, while he waited dumbly for the communication-cord to be pulled. The lady,<br />

however, contented herself with a silent stare at her strangely muffled companion. How much had she seen,<br />

Theodoric queried to himself, and in any case what on earth must she think of his present posture?<br />

2 “I think I have caught a chill,” he ventured desperately.<br />

3 “Really, I’m sorry,” she replied. “I was just going to ask you if you would open this window.”<br />

4 “I fancy it’s malaria,” he added, his teeth chattering slightly, as much from fright as from a desire to support<br />

his theory.<br />

5 “I’ve got some brandy in my hold-all, if you’ll kindly reach it down for me,” said his companion.<br />

6 “Not for worlds—I mean, I never take anything for it,” he assured her earnestly.<br />

7 “I suppose you caught it in the Tropics?”<br />

8 Theodoric, whose acquaintance with the Tropics was limited to an annual present of a chest of tea from an<br />

uncle in Ceylon, felt that even the malaria was slipping from him. Would it be possible, he wondered, to<br />

disclose the real state of affairs to her in small installments?<br />

9 “Are you afraid of mice?” he ventured, growing, if possible, more scarlet in the face.<br />

10 “Not unless they came in quantities, like those that ate up Bishop Hatto. Why do you ask?”<br />

11 “I had one crawling inside my clothes just now,” said Theodoric in a voice that hardly seemed his own. “It<br />

was a most awkward situation.”<br />

12 “It must have been, if you wear your clothes at all tight,” she observed; “but mice have strange ideas of<br />

comfort.”<br />

13 “I had to get rid of it while you were asleep,” he continued; then, with a gulp, he added, “it was getting rid<br />

of it that brought me to—to this.”<br />

14 “Surely leaving off one small mouse wouldn’t bring on a chill,” she exclaimed, with a levity that Theodoric<br />

accounted abominable.<br />

15 Evidently she had detected something of his predicament, and was enjoying his confusion. All the blood in<br />

his body seemed to have mobilized in one concentrated blush, and an agony of abasement, worse than a myriad<br />

mice, crept up and down over his soul. And then, as reflection began to assert itself, sheer terror took the place<br />

of humiliation. With every minute that passed the train was rushing nearer to the crowded and bustling terminus<br />

where dozens of prying eyes would be exchanged for the one paralyzing pair that watched him from the further<br />

corner of the carriage. There was one slender despairing chance, which the next few minutes must decide. His<br />

fellow-traveler might relapse into a blessed slumber. But as the minutes throbbed by that chance ebbed away.<br />

The furtive glance which Theodoric stole at her from time to time disclosed only an unwinking wakefulness.<br />

16 “I think we must be getting near now,” she presently observed.<br />

17 Theodoric had already noted with growing terror the recurring stacks of small, ugly dwellings that heralded<br />

the journey’s end. The words acted as a signal. Like a hunted beast breaking cover and dashing madly towards<br />

some other haven of momentary safety he threw aside his rug, and struggled frantically into his disheveled<br />

garments. He was conscious of dull suburban stations racing past the window, of a choking, hammering<br />

sensation in his throat and heart, and of an icy silence in that corner towards which he dared not look. Then as<br />

he sank back in his seat, clothed and almost delirious, the train slowed down to a final crawl, and the woman<br />

spoke.<br />

18 Would you be so kind,” she asked, “as to get me a porter to put me into a cab? It’s a shame to trouble you<br />

when you’re feeling unwell, but being blind makes one so helpless at a railway station.”<br />

Reading Comprehension<br />

32

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

____ 39. “The Mouse” is characteristic of realism because Saki —<br />

A. uses dialogue that captures the sounds of everyday speech<br />

B. portrays the lives and values of the lower class<br />

C. depicts the human condition in an objective manner<br />

D. has an interest in attaining social equality and exposing society’s ills<br />

____ 40. The author uses the phrase “Like a hunted beast breaking cover” to —<br />

A. show Theodoric’s concern for the mouse<br />

B. illustrate the other passenger’s reaction<br />

C. describe how frantically Theodoric moved<br />

D. describe how quickly the mouse moved<br />

33

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

Read this selection. Then answer the questions that follow it.<br />

The following excerpt is from a lecture that John Ruskin delivered in 1864. Ruskin was an influential social<br />

critic of the Victorian era.<br />

from Sesame: Of Kings’ Treasuries<br />

John Ruskin<br />

31. My friends, I do not know why any of us should talk about reading. We want some sharper<br />

discipline than that of reading; but, at all events, be assured, we cannot read. No reading is possible for a<br />

people with its mind in this state. No sentence of any great writer is intelligible to them. It is simply and<br />

sternly impossible for the English public, at this moment, to understand any thoughtful writing,—so<br />

incapable of thought has it become in its insanity of avarice. Happily, our disease is, as yet, little worse<br />

than this incapacity of thought; it is not corruption of the inner nature; we ring true still, when anything<br />

strikes home to us; and though the idea that everything should “pay” has infected our every purpose so<br />

deeply, that even when we would play the good Samaritan, we never take out our twopence and give them<br />

to the host without saying, “When I come again, thou shalt give me fourpence,” there is a capacity of noble<br />

passion left in our hearts’ core. We show it in our work,—in our war,—even in those unjust domestic<br />

affections which make us furious at a small private wrong, while we are polite to a boundless public one:<br />

we are still industrious to the last hour of the day, though we add the gambler’s fury to the laborer’s<br />

patience; we are still brave to the death, though incapable of discerning true cause for battle; and are still<br />

true in affection to our own flesh, to the death, as the sea-monsters are, and the rock-eagles. And there is<br />

hope for a nation while this can still be said for it. As long as it holds its life in its hand, ready to give it for<br />

its honor (though a foolish honor), for its love (though a selfish love), and for its business (though a base<br />

business), there is hope for it. But hope only; for this instinctive, reckless virtue cannot last. No nation can<br />

last, which has made a mob of itself, however generous at heart. It must discipline its passions, and direct<br />

them, or they will discipline it, one day, with scorpion whips. Above all a nation cannot last as a<br />

money-making mob: it cannot with impunity,—it cannot with existence,—go on despising literature,<br />

despising science, despising art, despising nature, despising compassion, and concentrating its soul on<br />

Pence. Do you think these are harsh or wild words? Have patience with me but a little longer. I will prove<br />

their truth to you, clause by clause.<br />

34

Name: ________________________<br />

ID: A<br />

32. I.—I say first we have despised literature. What do we, as a nation, care about books? How much<br />

do you think we spend altogether on our libraries, public or private, as compared with what we spend on<br />

our horses? If a man spends lavishly on his library you call him mad—a bibliomaniac. But you never call<br />

any one a horse-maniac, though men ruin themselves every day by their horses, and you do not hear of<br />

people ruining themselves by their books. Or, to go lower still, how much do you think the contents of the<br />

bookshelves of the United Kingdom, public and private, would fetch, as compared with the contents of its<br />

wine-cellars? What position would its expenditure on literature take, as compared with its expenditure on<br />

luxurious eating? We talk of food for the mind, as of food for the body; now a good book contains such<br />

food inexhaustibly; it is a provision for life, and for the best part of us; yet how long most people would<br />

look at the best book before they would give the price of a large turbot for it! though there have been men<br />

who have pinched their stomachs and bared their backs to buy a book, whose libraries were cheaper to<br />

them, I think, in the end, than most men’s dinners are. We are few of us put to such trial, and more the pity;<br />