Extraordinary features of the reproductive biology of Marchantia at ...

Extraordinary features of the reproductive biology of Marchantia at ...

Extraordinary features of the reproductive biology of Marchantia at ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

(a)<br />

Article<br />

<strong>Marchantia</strong> reproduction <strong>at</strong> Thursley<br />

Anything on <strong>the</strong> verge <strong>of</strong> extinction is<br />

given to excesses <strong>of</strong> <strong>reproductive</strong> activity<br />

(Steinbeck, 1994)<br />

Jeffrey G Duckett and Silvia Pressel<br />

report <strong>the</strong>ir l<strong>at</strong>est observ<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> sexual<br />

reproduction in <strong>Marchantia</strong> polymorpha<br />

in <strong>the</strong> unique post-fire habit<strong>at</strong> <strong>at</strong> Thursley<br />

Common NNR in Surrey.<br />

<strong>Extraordinary</strong><br />

<strong>fe<strong>at</strong>ures</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>reproductive</strong><br />

<strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Marchantia</strong><br />

<strong>at</strong> Thursley<br />

Common<br />

(b)<br />

(c)<br />

Sometimes major environmental<br />

disasters provide unique opportunities<br />

for uncovering new aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

plant <strong>reproductive</strong> <strong>biology</strong>. Thus a<br />

study <strong>of</strong> bryophyte recoloniz<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>of</strong> Thursley Common NNR, 1 year after <strong>the</strong><br />

fire <strong>of</strong> 2006 (Duckett et al., 2008), has revealed<br />

major differences in <strong>the</strong> provenance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

bryophytes colonizing <strong>the</strong> burnt areas. Whereas<br />

some have persisted via underground stems (e.g.<br />

Campylopus and Polytrichum species), o<strong>the</strong>rs are<br />

new arrivals via spores (e.g. Cer<strong>at</strong>odon purpureus<br />

and Funaria hygrometrica). Most striking among<br />

<strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter was <strong>Marchantia</strong> polymorpha which<br />

formed huge p<strong>at</strong>ches up to 12 m in diameter<br />

made up <strong>of</strong> individual colonies 5–20 cm in<br />

diameter. Continued monitoring <strong>at</strong> Thursley<br />

Common has now revealed hi<strong>the</strong>rto unsuspected<br />

and remarkable <strong>fe<strong>at</strong>ures</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>reproductive</strong><br />

<strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha th<strong>at</strong> do not accord<br />

with inform<strong>at</strong>ion th<strong>at</strong> has been repe<strong>at</strong>ed virtually<br />

unchanged in <strong>the</strong> general liter<strong>at</strong>ure since <strong>the</strong><br />

original generic account by Goebel (1905). Our<br />

new findings are <strong>the</strong> subject <strong>of</strong> this report.<br />

Perceived wisdom on sexual reproduction in<br />

<strong>Marchantia</strong><br />

Goebel (1905), Parihar (1961) and Crum<br />

(2001) present more or less consistent accounts<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> events leading to sporophyte m<strong>at</strong>ur<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

in M. polymorpha. The an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores begin<br />

to m<strong>at</strong>ure first and fertiliz<strong>at</strong>ion is generally<br />

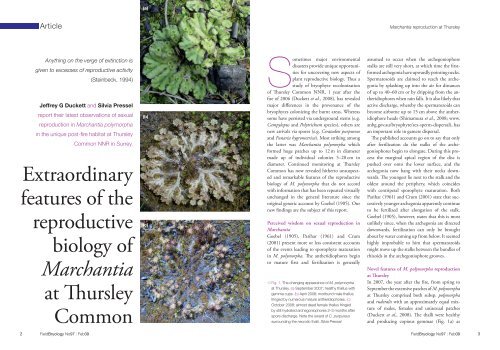

v Fig. 1. The changing appearance <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha<br />

<strong>at</strong> Thursley. (a) September 2007; healthy thallus with<br />

gemma cups. (b) April 2008; moribund male thallus<br />

fringed by numerous m<strong>at</strong>ure an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores. (c)<br />

October 2008; almost dead female thallus fringed<br />

by still hydr<strong>at</strong>ed archegoniophores 2–3 months after<br />

spore discharge. Note <strong>the</strong> sward <strong>of</strong> C. purpureus<br />

surrounding <strong>the</strong> necrotic thalli. Silvia Pressel<br />

assumed to occur when <strong>the</strong> archegoniophore<br />

stalks are still very short, <strong>at</strong> which time <strong>the</strong> firstformed<br />

archegonia have upwardly pointing necks.<br />

Sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids are claimed to reach <strong>the</strong> archegonia<br />

by splashing up into <strong>the</strong> air for distances<br />

<strong>of</strong> up to 40–60 cm or by dripping from <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores<br />

when rain falls. It is also likely th<strong>at</strong><br />

active discharge, whereby <strong>the</strong> sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids can<br />

become airborne up to 15 cm above <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore<br />

heads (Shimamura et al., 2008; www.<br />

anbg.gov.au/bryophyte/sex-sperm-dispersal), has<br />

an important role in gamete dispersal.<br />

The published accounts go on to say th<strong>at</strong> only<br />

after fertiliz<strong>at</strong>ion do <strong>the</strong> stalks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> archegoniophores<br />

begin to elong<strong>at</strong>e. During this process<br />

<strong>the</strong> marginal apical region <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> disc is<br />

pushed over onto <strong>the</strong> lower surface, and <strong>the</strong><br />

archegonia now hang with <strong>the</strong>ir necks downwards.<br />

The youngest lie next to <strong>the</strong> stalk and <strong>the</strong><br />

oldest around <strong>the</strong> periphery, which coincides<br />

with centripetal sporophyte m<strong>at</strong>ur<strong>at</strong>ion. Both<br />

Parihar (1961) and Crum (2001) st<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> successively<br />

younger archegonia apparently continue<br />

to be fertilized after elong<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stalk.<br />

Goebel (1905), however, st<strong>at</strong>es th<strong>at</strong> this is most<br />

unlikely since, when <strong>the</strong> archegonia are directed<br />

downwards, fertiliz<strong>at</strong>ion can only be brought<br />

about by w<strong>at</strong>er coming up from below. It seemed<br />

highly improbable to him th<strong>at</strong> sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids<br />

might move up <strong>the</strong> stalks between <strong>the</strong> bundles <strong>of</strong><br />

rhizoids in <strong>the</strong> archegoniophore grooves.<br />

Novel <strong>fe<strong>at</strong>ures</strong> <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha reproduction<br />

<strong>at</strong> Thursley<br />

In 2007, <strong>the</strong> year after <strong>the</strong> fire, from spring to<br />

September <strong>the</strong> extensive p<strong>at</strong>ches <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha<br />

<strong>at</strong> Thursley comprised both subsp. polymorpha<br />

and ruderalis with an approxim<strong>at</strong>ely equal mixture<br />

<strong>of</strong> males, females and unisexual p<strong>at</strong>ches<br />

(Duckett et al., 2008). The thalli were healthy<br />

and producing copious gemmae (Fig. 1a) as<br />

2 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 3

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

(a)<br />

n Fig. 2. Healthy male thalli from a damp depression on <strong>the</strong> Common. (a) June 2008; a mixture <strong>of</strong> m<strong>at</strong>ure<br />

an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores produced <strong>the</strong> previous winter and young spring primordia th<strong>at</strong> gradually m<strong>at</strong>ure during <strong>the</strong> summer<br />

months. (b) November 2008; male thalli lacking gemma cups and fringed with an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore primordia. Note <strong>the</strong><br />

Polytrichum stems overgrowing <strong>the</strong> <strong>Marchantia</strong>. Silvia Pressel<br />

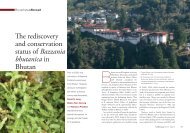

x Fig. 3. Ventral aspect <strong>of</strong> archegoniophore caps. (a) Cap with 13 m<strong>at</strong>ure peripheral sporophytes and approxim<strong>at</strong>ely<br />

40 perianths containing imm<strong>at</strong>ure sporophytes nearer <strong>the</strong> central stalk (removed). (b) Cap with all <strong>the</strong> m<strong>at</strong>ure<br />

sporophytes liber<strong>at</strong>ing <strong>the</strong>ir spores after 30 minutes drying out <strong>at</strong> room temper<strong>at</strong>ure. (c) Cap remaining hydr<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

2–3 months after spore liber<strong>at</strong>ion. Silvia Pressel<br />

well as numerous an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores and archegoniophores<br />

around <strong>the</strong> margins. By l<strong>at</strong>e June<br />

2007 every archegoniophore, even those on<br />

females several tens <strong>of</strong> centimetres or more from<br />

<strong>the</strong> nearest male colony was producing numerous<br />

sporophytes. From <strong>the</strong>se observ<strong>at</strong>ions we concluded<br />

th<strong>at</strong> M. polymorpha arrived <strong>at</strong> Thursley via<br />

wind-blown spores and, whilst <strong>the</strong> p<strong>at</strong>ches <strong>of</strong><br />

unisexual plants were almost certainly clones<br />

derived from gemmae, cross-fertiliz<strong>at</strong>ion was<br />

also highly effective belying <strong>the</strong> widely held<br />

notion th<strong>at</strong> sexual reproduction involving motile<br />

sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids is problem<strong>at</strong>ic on land.<br />

By November 2007 <strong>the</strong> central parts <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong><br />

M. polymorpha colonies on fl<strong>at</strong> open areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Common were moribund. Very few were still<br />

producing new gemma cups and <strong>the</strong> margins<br />

were fringed by wi<strong>the</strong>red an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores and<br />

archegoniophores th<strong>at</strong> had ceased to produce<br />

an<strong>the</strong>ridia and sporophytes, respectively, by<br />

September 2007. In damper hollows, however,<br />

<strong>the</strong> margins <strong>of</strong> healthier green male thalli were<br />

fringed with abundant an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore primordia<br />

(Fig. 2). They remained in this condition<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> winter <strong>of</strong> 2007–2008.<br />

Archegoniophore primordia first appeared along<br />

<strong>the</strong> margins <strong>of</strong> adjacent healthy female plants in<br />

March 2008.<br />

To our surprise, early April 2008 saw most <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> thalli on <strong>the</strong> open he<strong>at</strong>h in <strong>the</strong> same moribund<br />

condition as during <strong>the</strong> winter months with<br />

little or no new gemma production. Remarkably,<br />

however, production <strong>of</strong> carpocephala around<br />

<strong>the</strong> margins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se unhealthy thalli was just as<br />

prolific as in 2007, but <strong>the</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

sexes was different with mixed colonies far more<br />

abundant than in 2007. This we interpret as<br />

<strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> new colonies becoming established<br />

from spores released <strong>at</strong> Thursley in <strong>the</strong> previous<br />

summer. The vast majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> surviving thalli<br />

were subsp. polymorpha with very few <strong>of</strong> subsp.<br />

ruderalis.<br />

By April 2008 <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores, initi<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

<strong>the</strong> previous autumn, had m<strong>at</strong>ured and were<br />

actively discharging sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids. In contrast,<br />

all <strong>the</strong> archegoniophores had short stalks and<br />

m<strong>at</strong>ure and developing archegonia th<strong>at</strong> had yet<br />

to be fertilized.<br />

The thalli were even more necrotic by mid-<br />

May, but by this time, despite 2 weeks without<br />

rain, nearly all <strong>the</strong> archegoniophores had fully<br />

elong<strong>at</strong>ed stalks. All <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores were<br />

still producing new an<strong>the</strong>ridia but <strong>the</strong> only<br />

archegoniophores th<strong>at</strong> bore young sporophytes<br />

were in mixed colonies (i.e. less than 5 cm from<br />

<strong>the</strong> nearest male). The sporophytes numbered<br />

from 1 to 10 per archegoniophore.<br />

Sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoid and sporophyte production<br />

continued throughout <strong>the</strong> summer <strong>of</strong> 2008 and<br />

from June onwards all but a few female plants<br />

several tens <strong>of</strong> centimetres removed from <strong>the</strong><br />

nearest males had or were producing numerous<br />

sporophytes. From a peak <strong>of</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore<br />

and archegoniophore m<strong>at</strong>ur<strong>at</strong>ion in June and<br />

July, smaller numbers continued to be produced<br />

well into November 2008. In addition to <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>e<br />

season carpocephala, many <strong>of</strong> those produced<br />

earlier in <strong>the</strong> spring and summer remained fully<br />

hydr<strong>at</strong>ed, though <strong>the</strong>y had discharged <strong>the</strong>ir con<br />

tents many months previously. The autumn <strong>of</strong><br />

2008 saw <strong>the</strong> nascence <strong>of</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore primordia<br />

(Fig. 2b) repe<strong>at</strong>ing <strong>the</strong> p<strong>at</strong>tern observed<br />

in 2007.<br />

Close scrutiny <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> archegoniophores<br />

revealed remarkable seasonal changes in <strong>the</strong><br />

numbers <strong>of</strong> sporophytes produced (Fig. 3).<br />

Those m<strong>at</strong>uring in May, and from August to<br />

November, bore numbers conforming to those<br />

given by P<strong>at</strong>on (1999) <strong>of</strong> up to 24 or more. Each<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 9–11 archegoniophore lobes produced<br />

1–3 sporophytes. In June and July, approxim<strong>at</strong>ely<br />

50% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> archegoniophores bore similar<br />

numbers <strong>of</strong> sporophytes. However, in <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

50% <strong>the</strong> numbers were much higher. The l<strong>at</strong>ter<br />

had up to 30–50 m<strong>at</strong>ure sporophytes with<br />

similar numbers <strong>of</strong> discharged ones around <strong>the</strong><br />

margins and younger ones nearer <strong>the</strong> central<br />

stalk, as noted previously by Parihar (1961)<br />

and Crum (2001). Many archegoniophores<br />

(b)<br />

(c)<br />

4 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 5

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

<strong>Marchantia</strong> reproduction <strong>at</strong> Thursley<br />

were thus producing a total <strong>of</strong> up to around<br />

100 sporophytes. The majority origin<strong>at</strong>ed from<br />

a single archegonium within each <strong>of</strong> numerous<br />

additional pseudoperianths, but in a few cases<br />

two archegonia had been fertilized. This is one<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> very few records <strong>of</strong> polysety in liverworts,<br />

a phenomenon th<strong>at</strong> is widespread in mosses<br />

(Longton, 1962; Milne, 2001). We could also<br />

find no evidence th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> additional sporophytes<br />

were <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> polyembryony as<br />

noted previously in Mannia (Udar & Chandra,<br />

1964).<br />

Given <strong>the</strong> massive scale <strong>of</strong> sporophyte production<br />

and <strong>the</strong> almost 100% fertiliz<strong>at</strong>ion efficiency<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>at</strong> least one archegonium within each<br />

pseudoperianth in every archegoniophore in <strong>the</strong><br />

Thursley M. polymorpha, we carried out some<br />

simple experiments with w<strong>at</strong>er drops containing<br />

dye (1% Methylene Blue) to explore <strong>the</strong> most<br />

likely routes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids from <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores<br />

to archegoniophores with alreadyextended<br />

stalks. The results were very different<br />

from those reported from previous experiments<br />

with <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridial heads <strong>of</strong> mosses, for example<br />

maximum splash distances <strong>of</strong> 50, 60 and<br />

230 cm in Mnium ciliare, Polytrichum ohiensis<br />

and Dawsonia superba, respectively (Longton,<br />

1994; Paolillo, 1981; Reynolds, 1980), and<br />

distances <strong>of</strong> 40–60 cm from male inflorescences<br />

in marchantialean liverworts (www.anbg.gov.au/<br />

bryophyte/sex-sperm-dispersal).<br />

When drops <strong>of</strong> dye-containing w<strong>at</strong>er were<br />

dropped onto <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore caps, <strong>the</strong><br />

splashing <strong>of</strong> droplets was extremely limited.<br />

Although a few dye-containing droplets landed<br />

up to 30 cm away from <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores,<br />

over 90% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> liquid was absorbed within<br />

seconds by <strong>the</strong> heads <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores<br />

and dye reached <strong>the</strong> thallus surface <strong>at</strong> ground<br />

level within minutes. In less than 1 h <strong>the</strong> dye had<br />

spread between <strong>the</strong> pegged rhizoids throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> ventral surface <strong>of</strong> entire colonies 10 cm<br />

in diameter. Conversely, when female thalli<br />

were placed in dye this reached <strong>the</strong> heads <strong>of</strong><br />

archegoniophores in 30–60 min (Duckett et al.,<br />

2009).<br />

Conclusions<br />

The cess<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> gemma production and de<strong>at</strong>h<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> thalli <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Thursley M. polymorpha in<br />

2008, 2 years after <strong>the</strong> gre<strong>at</strong> fire <strong>of</strong> 2006, can<br />

be easily interpreted as <strong>the</strong> consequence <strong>of</strong><br />

nutrient leaching [cf. early production <strong>of</strong> gemmae<br />

in C. purpureus and F. hygrometrica on<br />

bonfire sites and Bryum spp. in arable fields<br />

(Duckett et al., 2004; Pressel et al., 2007)] in line<br />

with <strong>the</strong> classic demonstr<strong>at</strong>ion by Wann (1925)<br />

th<strong>at</strong> low nitrogen in <strong>the</strong> culture medium also<br />

reduces gemma production. It is also noteworthy<br />

th<strong>at</strong> subsp. ruderalis, a taxon <strong>of</strong> presumably more<br />

nutrient-rich soils in gardens, greenhouses and<br />

nurseries, disappeared before subsp. polymorpha.<br />

(c)<br />

(e)<br />

(d)<br />

(f)<br />

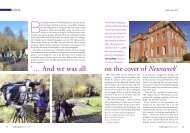

x Fig. 4. Scanning electron micrographs <strong>of</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha. (a) Vertical section through cap<br />

showing chambers with photosyn<strong>the</strong>tic lamellae, an<strong>the</strong>ridial cavities (arrowed) and pegged rhizoids running parallel<br />

to <strong>the</strong> lower surface. These rhizoids connect with those in <strong>the</strong> stalks (f). (b) Detail <strong>of</strong> air chambers containing<br />

photosyn<strong>the</strong>tic lamellae (arrowed). (c) Numerous pores, opening into ei<strong>the</strong>r an<strong>the</strong>ridial pits or <strong>the</strong> photosyn<strong>the</strong>tic air<br />

chambers, cover <strong>the</strong> upper surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores. In contrast to <strong>the</strong> w<strong>at</strong>er-repellent upper surfaces <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

archegoniophores, rain drops falling on <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores are rapidly absorbed and <strong>the</strong> w<strong>at</strong>er moves rapidly into<br />

<strong>the</strong> rhizoid wicks running parallel to <strong>the</strong> lower surface and <strong>the</strong>n down <strong>the</strong> stalks taking <strong>the</strong> sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids with it. (d)<br />

Detail <strong>of</strong> an an<strong>the</strong>ridial pore (right) and a pore opening into a photosyn<strong>the</strong>tic chamber. (e) Closely overlapping scales<br />

on <strong>the</strong> lower surface <strong>of</strong> an an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore cap. (f) Pegged rhizoids in an an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore stalk. Bars, (a, c, e) 500 µm;<br />

(b, d, f) 100 µm. Jeff Duckett<br />

6 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 7

<strong>Marchantia</strong> reproduction <strong>at</strong> Thursley<br />

<strong>Marchantia</strong> reproduction <strong>at</strong> Thursley<br />

The rapid demise <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong>se taxa and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

dependency on high soil nutrient levels is<br />

also very likely to be rel<strong>at</strong>ed to <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong><br />

endophytic glomeromycotean fungi (Ligrone et<br />

al., 2007). These fungi are ubiquitous in o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

British <strong>Marchantia</strong>les (except <strong>the</strong> Ricciaceae),<br />

including M. polymorpha subsp. montivagans.<br />

Whilst <strong>the</strong> change in veget<strong>at</strong>ive vigour <strong>of</strong><br />

M. polymorpha between 2007 and 2008 was as<br />

might be expected, <strong>the</strong> undiminished form<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>of</strong> carpocephala by moribund thalli, not to<br />

mention <strong>the</strong> massively enhanced production <strong>of</strong><br />

sporophytes, was most surprising.<br />

Carpocephalum ontogeny, longevity and <strong>the</strong><br />

period <strong>of</strong> sexual activity in M. polymorpha (<strong>at</strong> least<br />

<strong>at</strong> Thursley) appears to be far more protracted<br />

than th<strong>at</strong> recorded in all o<strong>the</strong>r carpocephal<strong>at</strong>e<br />

<strong>Marchantia</strong>les. An<strong>the</strong>ridium production by <strong>the</strong><br />

same an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore extends over <strong>at</strong> least a<br />

4-month period (April–July), archegonium<br />

form<strong>at</strong>ion by only a slightly shorter time span<br />

and sporophyte production for 6–8 months<br />

from l<strong>at</strong>e April until November. These months<br />

are different from those given by P<strong>at</strong>on (1999),<br />

i.e. July–November. By comparison, <strong>the</strong> archegoniophores<br />

<strong>of</strong> Conocephalum conicum and<br />

Lunularia cruci<strong>at</strong>a in sou<strong>the</strong>rn England persist<br />

for only 2–3 weeks in February and March.<br />

Those produced by a popul<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Reboulia<br />

hemisphaerica close to Thursley NNR have<br />

nearly m<strong>at</strong>ure sporophytes in April, but shrivel<br />

and virtually disappear a month l<strong>at</strong>er.<br />

These observ<strong>at</strong>ions on <strong>the</strong> <strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha<br />

<strong>at</strong> Thursley suggest day length as <strong>the</strong><br />

most likely trigger for <strong>the</strong> initi<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> sexual<br />

reproduction. Appearance <strong>of</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore<br />

primordia in <strong>the</strong> autumn indic<strong>at</strong>es this to be<br />

a short-day response, whilst long days lead<br />

to <strong>the</strong> spring initi<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> archegoniophores,<br />

<strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter conclusion being in line with earlier<br />

experimental studies (Chopra & Kumra, 1988).<br />

In contrast, <strong>the</strong> autumn appearance <strong>of</strong> male<br />

and female sex organs in L. cruci<strong>at</strong>a, C. conicum<br />

and R. hemisphaerica suggest th<strong>at</strong> both are<br />

initi<strong>at</strong>ed in response to short days in <strong>the</strong>se three<br />

genera.<br />

The moribund condition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> M. polymorpha<br />

thalli <strong>at</strong> Thursley in 2008 clearly indic<strong>at</strong>es th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

growth, m<strong>at</strong>ur<strong>at</strong>ion and persistence <strong>of</strong> its stalked<br />

carpocephala appear to be largely independent <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> health <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> parent thalli (Fig. 1b, c). With<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir well-developed air chambers and photosyn<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

lamellae, <strong>the</strong>y clearly function independently<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> photosyn<strong>the</strong>sis (Fig. 4a, b).<br />

This still begs <strong>the</strong> question as to how <strong>the</strong>y can<br />

remain fully hydr<strong>at</strong>ed long after sperm and spore<br />

discharge. Whereas nearly all <strong>the</strong> mosses growing<br />

in <strong>the</strong> vicinity <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha (see Duckett<br />

et al., 2008 for listing) become desicc<strong>at</strong>ed after<br />

a few days without rain, <strong>the</strong> carpocephala appear<br />

to be largely unaffected by short dry periods.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> dye experiments demonstr<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong><br />

an<strong>the</strong>ridiophore caps readily absorb w<strong>at</strong>er directly,<br />

<strong>the</strong> only source <strong>of</strong> w<strong>at</strong>er for <strong>the</strong> w<strong>at</strong>er-repellent<br />

archegoniophore caps (and <strong>the</strong> upper surface<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> thalli with <strong>the</strong> same properties) is via <strong>the</strong><br />

rhizoidal grooves in <strong>the</strong>ir stalks (Fig. 4f). The dye<br />

movement experiments show th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>se function<br />

most effectively as an internalized external w<strong>at</strong>erconducting<br />

system th<strong>at</strong> is far more effective <strong>at</strong><br />

maintaining w<strong>at</strong>er balance than even <strong>the</strong> most<br />

highly differenti<strong>at</strong>ed hydroid strands in polytrichalean<br />

mosses (Ligrone et al., 2000; Duckett<br />

et al., 2009). Contrary to Goebel’s (1905) view<br />

this study shows th<strong>at</strong>, in addition to maintaining<br />

<strong>the</strong> w<strong>at</strong>er content <strong>of</strong> carpocephala, <strong>the</strong> rhizoid<br />

grooves could also function as extremely effective<br />

conduits for sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids after archegoniophore<br />

stalk elong<strong>at</strong>ion. Given <strong>the</strong> demonstr<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

th<strong>at</strong> splashing and dripping <strong>of</strong> sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids<br />

from raindrops falling on <strong>the</strong> an<strong>the</strong>ridiophores<br />

is not very effective, we conclude th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> dissemin<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>of</strong> most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> male gametes between<br />

thalli <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha, <strong>of</strong>ten tens <strong>of</strong> centimetres<br />

apart, is almost certainly via surface w<strong>at</strong>er films<br />

as originally described by Muggoch & Walton<br />

(1942). Explosive sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoid discharge may<br />

also play a part but on a very local scale.<br />

It is interesting to note th<strong>at</strong> <strong>Marchantia</strong>, <strong>the</strong><br />

marchantialian genus with <strong>the</strong> most persistent<br />

archegoniophores and <strong>the</strong> only one with stalked<br />

an<strong>the</strong>ridium-bearing counterparts, has 2–4<br />

rhizoid grooves and some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most highly<br />

differenti<strong>at</strong>ed pegged rhizoids within <strong>the</strong>se<br />

(Duckett et al., 2009; Schuster, 1992). Many<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> order have only one groove<br />

(Aytoniaceae, Conocephalum) or lack this fe<strong>at</strong>ure<br />

altoge<strong>the</strong>r (Lunularia).<br />

The numbers <strong>of</strong> sporophytes produced per<br />

archegoniophore by M. polymorpha <strong>at</strong> Thursley<br />

stands out as extremely high against P<strong>at</strong>on’s<br />

(1999) figure <strong>of</strong> 24 or more, and even more so<br />

compared with numbers in o<strong>the</strong>r carpocephal<strong>at</strong>e<br />

<strong>Marchantia</strong>les. Sporophyte numbers in o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

genera range from up to 9 in Dumortiera, up to<br />

8 in Conocephalum, Peltolepis and Preissia, 7 in<br />

Reboulia, 4–5 in Asterella, Mannia and Sauteria,<br />

3–4 in Athalamia but only 1–4 in Plagiochasma<br />

(P<strong>at</strong>on, 1999; Schuster, 1992). However, in all<br />

<strong>the</strong>se genera, m<strong>at</strong>ure archegoniophores without<br />

sporophytes are extremely rare, indic<strong>at</strong>ing th<strong>at</strong><br />

highly effective sexual reproduction is a hallmark<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Marchantia</strong>les.<br />

In addition to rapid growth r<strong>at</strong>es and small<br />

spore size (Duckett et al., 2008), exceedingly<br />

efficient sexual reproduction and, with this,<br />

extraordinary spore production can be added to<br />

key <strong>fe<strong>at</strong>ures</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Marchantia</strong> th<strong>at</strong><br />

contribute to <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genus as a primary<br />

colonist. With 300,000 spores per capsule, single<br />

archegoniophores <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha <strong>at</strong> Thursley,<br />

bearing 100 sporophytes, are producing no fewer<br />

than 30 million spores. Though not quite as<br />

high as <strong>the</strong> spore maximum per capsule for bryophytes<br />

[80 million in <strong>the</strong> moss genus Dawsonia –<br />

this figure is more likely to be 67,108,864<br />

when calcul<strong>at</strong>ed from 226 cell divisions from<br />

<strong>the</strong> spore initial in nascent capsules (Parihar,<br />

1961; Longton, 1994)] spore production in<br />

M. polymorpha embodies considerably gre<strong>at</strong>er<br />

potential for genetic diversity with dioecy<br />

ensuring outbreeding followed by 100 different<br />

sexual unions and millions <strong>of</strong> meiotic products<br />

being dissemin<strong>at</strong>ed from every archegoniophore.<br />

This highly robust genetic system may explain<br />

why M. polymorpha is <strong>the</strong> sole British liverwort<br />

with three well-recognized subspecies (P<strong>at</strong>on,<br />

1999) and also suggests th<strong>at</strong> M. polymorpha<br />

might be a bryophyte particularly well equipped<br />

to survive clim<strong>at</strong>e change.<br />

Although this account provides a functional<br />

explan<strong>at</strong>ion for <strong>the</strong> prolonged survival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> carpocephala<br />

in M. polymorpha and <strong>the</strong> likely route<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sperm<strong>at</strong>ozoids for highly effective fertiliz<strong>at</strong>ion,<br />

we have little or no clues as to <strong>the</strong> possible<br />

reasons for <strong>the</strong> unusually high number <strong>of</strong><br />

pseudoperianths and sporophytes. One possible<br />

explan<strong>at</strong>ion is th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>se excesses <strong>of</strong> sexual<br />

activity are triggered by falling nutrient levels;<br />

<strong>the</strong>se may well be a regular fe<strong>at</strong>ure <strong>of</strong> <strong>Marchantia</strong><br />

popul<strong>at</strong>ions on <strong>the</strong> verge <strong>of</strong> extinction. As to<br />

<strong>the</strong> future <strong>of</strong> M. polymorpha <strong>at</strong> Thursley, fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

fires not withstanding, it would seem highly<br />

unlikely th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> moribund<br />

thalli in open areas will survive for more than 1<br />

or 2 years; in <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>e summer and autumn <strong>of</strong><br />

2008 <strong>the</strong>se were clearly being overgrown by<br />

rampant C. purpureus, Campylopus intr<strong>of</strong>lexus<br />

and Polytrichum juniperinum (Fig. 5). Longterm<br />

survival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> healthier thalli in damper<br />

8 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 9

(a) (b) (c)<br />

n Fig. 5. The changing appearance <strong>of</strong> burnt dry he<strong>at</strong>h <strong>at</strong> Thursley. (a) November 2007–April 2008; extensive p<strong>at</strong>ches<br />

<strong>of</strong> Cer<strong>at</strong>odon purpureus, Campylopus intr<strong>of</strong>lexus and Polytrichum spp. (b) May–June 2008; vigorous regrowth <strong>of</strong><br />

sc<strong>at</strong>tered Calluna and Erica cinerea, but large areas <strong>of</strong> bare ground remain. (c) By October 2008 most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> burnt<br />

dry he<strong>at</strong>h is covered by with a continuous moss lawn. Also note <strong>the</strong> Betula seedlings. Silvia Pressel<br />

hollows is equally bleak since <strong>the</strong>se were completely<br />

overgrown by swards <strong>of</strong> Polytrichastrum<br />

formosum and Polytrichum commune by <strong>the</strong><br />

autumn <strong>of</strong> 2008.<br />

The results <strong>of</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r recording <strong>of</strong> bryophytes<br />

<strong>at</strong> Thursley, including <strong>the</strong> <strong>reproductive</strong> cycles<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mosses and <strong>the</strong> much l<strong>at</strong>er reappearance <strong>of</strong><br />

liverworts on <strong>the</strong> burned areas, will be <strong>the</strong> subject<br />

<strong>of</strong> future contributions to Field Bryology.<br />

Jeffrey G. Duckett & Silvia Pressel<br />

School <strong>of</strong> Biological and Chemical Sciences,<br />

Fogg Building, Queen Mary University <strong>of</strong><br />

London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS<br />

(e j.g.duckett@qmul.ac.uk, s.pressel@qmul.ac.uk)<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

S.P. acknowledges <strong>the</strong> financial support <strong>of</strong> a Leverhulme Trust<br />

Early Career Fellowship. We thank Karen Renzaglia and <strong>the</strong><br />

staff <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> IMAGE Center (Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Illinois University) for<br />

labor<strong>at</strong>ory and electron microscope facilities.<br />

References<br />

Chopra, R.N. & Kumra, P.K. (1988). Biology <strong>of</strong> Bryophytes.<br />

New Delhi: Wiley Eastern Ltd.<br />

Crum, H.A. (2001). Structural Diversity <strong>of</strong> Bryophytes. Ann<br />

Arbor: University <strong>of</strong> Michigan Herbarium.<br />

Duckett, J.G., Fletcher, P., Francis, R., M<strong>at</strong>cham, H.W.,<br />

Russell, A.J. & Pressel, S. (2004). In vitro cultiv<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong><br />

bryophytes; practicalities, progress, problems and promise.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Bryology 26, 3–20.<br />

Duckett, J.G., M<strong>at</strong>cham, H.W. & Pressel, S. (2008). Thursley<br />

Common NNR: bryophyte recoloniz<strong>at</strong>ion one year after <strong>the</strong><br />

gre<strong>at</strong> fire <strong>of</strong> July 2006. Field Bryology 94, 3–11.<br />

Duckett, J. G., Ligrone, R. & Renzaglia, K.S. (2009). Pegged<br />

and smooth rhizoids in complex thalloid liverworts: structure,<br />

function and evolution. Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Journal <strong>of</strong> Plant<br />

Sciences (in press).<br />

Goebel, K. (1905). Organography <strong>of</strong> Plants. Transl<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

I.B. Balfour. Oxford: Clarendon Press.<br />

Ligrone, R., Duckett, J.G. & Renzaglia K.S. (2000). Conducting<br />

tissues and phyletic rel<strong>at</strong>ionships <strong>of</strong> bryophytes. Philosophical<br />

Transactions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Royal Society B 355, 795–814.<br />

Ligrone, R., Carafa, A., Bonfante, P., Biancotta, V. &<br />

Duckett, J.G. (2007). Glomeromycotean associ<strong>at</strong>ions in<br />

liverworts: a molecular, cytological and taxonomical survey.<br />

American Journal <strong>of</strong> Botany 94, 1756–1777.<br />

Longton R. E. (1962). Polysety in <strong>the</strong> British Bryophyta.<br />

Transactions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> British Bryological Society 4, 326–333.<br />

Longton, R. E. (1994). Reproductive <strong>biology</strong> in bryophytes<br />

<strong>the</strong> challenge and <strong>the</strong> opportunities. Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> H<strong>at</strong>tori<br />

Botanical Labor<strong>at</strong>ory 76, 159–172.<br />

Milne, J. (2001). Reproductive <strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong> three Australian<br />

species <strong>of</strong> Dicranoloma (Bryopsida, Dicranaceae): sexual<br />

reproduction and phenology. Bryologist 104, 440–<br />

452.<br />

Muggoch, H. & Walton, J. (1942). On <strong>the</strong> dehiscence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

an<strong>the</strong>ridium and <strong>the</strong> part played by surface tension in <strong>the</strong><br />

dispersal <strong>of</strong> sperm<strong>at</strong>ocytes in Bryophyta. Proceedings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Royal Society London B 130, 448–461.<br />

Paolillo, D.J. (1981). The swimming sperms <strong>of</strong> land plants.<br />

BioScience 31, 367–373.<br />

Parihar, N.S. (1961). An Introduction to Embryophyta. Volume I.<br />

Bryophyta, 4th edn. Allahabad: Central Book Depot.<br />

P<strong>at</strong>on, J.A. (1999). The Liverwort Flora <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> British Isles.<br />

Colchester: Harley Books.<br />

Pressel, S., M<strong>at</strong>cham, H.W. & Duckett, J.G. (2007). Studies<br />

<strong>of</strong> protonemal morphogenesis in mosses. XI. Bryum and<br />

rel<strong>at</strong>ed genera; a plethora <strong>of</strong> propagules. Journal <strong>of</strong> Bryology<br />

29, 241–258.<br />

Reynolds, D.N. (1980). Gamete dispersal in Mnium ciliare.<br />

Bryologist 83, 73–77.<br />

Schuster, R.M. (1992). The Hep<strong>at</strong>icae and Anthocerotae<br />

<strong>of</strong> North America. Volume VI. Field Museum <strong>of</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ural<br />

History, Chicago.<br />

Shimamura, M. Yamaguchi, T. & Deguchi, H. (2008).<br />

Airborne sperm <strong>of</strong> Conocephalum conicum (Conocephalaceae).<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Plant Research 121, 69–71.<br />

Steinbeck, J. (1994). Cannery Row. London: Penguin<br />

Classics.<br />

Udar, R. & Chandra, V. (1964). Polyembryony in Mannia<br />

foreaui Udar et Chandra. Bryologist 67b, 55–59.<br />

Wann, F.B. (1925). Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> factors involved in sexual<br />

reproduction <strong>of</strong> <strong>Marchantia</strong> polymorpha. American Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Botany 12, 307–318.<br />

10 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 FieldBryology No97 | Feb09 11