Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

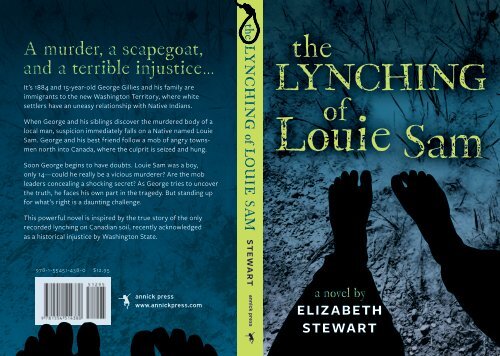

A murder, a scapegoat,<br />

and a terrible injustice . . .<br />

It’s 1884 and 15-year-old George Gillies and his family are<br />

immigrants to the new Washington Territory, where white<br />

settlers have an uneasy relationship with Native Indians.<br />

When George and his siblings discover the murdered body of a<br />

local man, suspicion immediately falls on a Native named Louie<br />

Sam. George and his best friend follow a mob of angry townsmen<br />

north into Canada, where the culprit is seized and hung.<br />

the<br />

<strong>Lynching</strong><br />

of<br />

Louie Sam<br />

Soon George begins to have doubts. Louie Sam was a boy,<br />

only 14—could he really be a vicious murderer? Are the mob<br />

leaders concealing a shocking secret? As George tries to uncover<br />

the truth, he faces his own part in the tragedy. But standing up<br />

for what’s right is a daunting challenge.<br />

This powerful novel is inspired by the true story of the only<br />

recorded lynching on Canadian soil, recently acknowledged<br />

as a historical injustice by Washington State.<br />

978-1-55451-438-0 $12.95<br />

a novel by<br />

Elizabeth<br />

Stewart

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

© 2012 Elizabeth Stewart<br />

<strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> Ltd.<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyrights hereon may<br />

be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or<br />

mechanical— without the prior written permission of the publisher.<br />

Edited by Pam Robertson<br />

Copyedited by Linda Pruessen<br />

Cover design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design<br />

Cover background image © lama-photography / photocase.com<br />

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario<br />

Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund<br />

(CBF) for our publishing activities.<br />

Cataloging in Publication<br />

Stewart, Elizabeth (Elizabeth Mary)<br />

The lynching of Louie Sam / Elizabeth Stewart.<br />

ISBN 978-1-55451-439-7 (bound).—ISBN 978-1-55451-438-0 (pbk.)<br />

1. Sam, Louie, d. 1884—Juvenile fiction. 2. British Columbia—<br />

History—1871-1918—Juvenile fiction. I. Title.<br />

Author’s Note<br />

On the night of February 27, 1884, two white teenagers<br />

followed a lynch mob comprised of their fathers and<br />

almost a hundred other American settlers north from the<br />

Washington Territory into British Columbia, Canada.<br />

There they seized Louie Sam, a member of the Stó:lō<br />

First Nation, from lawful custody and hung him, claiming<br />

he was guilty of murdering one of their own. This novel<br />

is the fictionalized story of those two teenagers, George<br />

Gillies and Peter Harkness. Readers should be advised that<br />

the racism expressed by these and other characters, while<br />

offensive, is meant to reflect the attitudes of the period.<br />

I have taken care in writing this historical fiction not to<br />

presume to express the thoughts or feelings of Louie Sam<br />

or the Stó:lō people, apart from what has been reported in<br />

the public record. The story of Louie Sam—who he was<br />

and what the injustice of his death meant and continues to<br />

mean to the Stó:lō Nation—remains to be told.<br />

PS8637.T49445L96 2012 jC813'.6 C2012-901957-7<br />

Distributed in Canada by:<br />

Firefly Books Ltd.<br />

66 Leek Crescent<br />

Richmond Hill, ON<br />

L4B 1H1<br />

Published in the U.S.A. by<br />

<strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> (U.S.) Ltd.<br />

Distributed in the U.S.A. by:<br />

Firefly Books (U.S.) Inc.<br />

P.O. Box 1338<br />

Ellicott Station<br />

Buffalo, NY 14205<br />

Printed in Canada<br />

Visit us at: www.annickpress.com

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

According to the Tuskegee Institute of Alabama, between<br />

1882 and 1968 there were 4,742 lynchings in the United<br />

States. In Canada during the same period there was one—<br />

the lynching of Louie Sam.<br />

For Louie Sam<br />

“Groups tend to be more immoral than<br />

individuals.”<br />

—Martin Luther King Junior

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

Chapter One<br />

Washington Territory, 1884<br />

My name is George Gillies. My parents are<br />

Scottish by birth and I was born in England, but since<br />

we immigrated, we’re all Americans now. We live near<br />

the town of Nooksack in the Washington Territory,<br />

just south of the International Border with British<br />

Columbia, Canada. Mam says the way we children<br />

speak, we sound just like we were born here.<br />

In Scotland and England, my father, Peter Gillies,<br />

worked the farmlands of one rich laird after another.<br />

He likes to tell anyone who will listen that we came<br />

to America for freedom’s sake—by which, he’ll add<br />

with a wink, he means the land he purchased almost<br />

for free from lumbermen here in the Nooksack Valley.<br />

Father considered it a bargain because the land had<br />

already been cleared of the giant fir trees that grow in<br />

these parts to a hundred feet or more. Our house is a<br />

log cabin made from those firs, but we have plans to<br />

build a fine two-story plank house one day.<br />

7

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

Father likes his joke, but he is serious about<br />

freedom, too. He tells us kids never to forget that the<br />

land we own is ours for all time and makes us free in<br />

ways we never could have been in Great Britain. Here,<br />

Father answers to no one but himself and God. And<br />

Mam says he only answers to God on Sundays.<br />

A couple of years back, my brothers and I helped<br />

Father build a dam on Sumas Creek, which cuts<br />

through our land. We run a gristmill off the millpond<br />

that resulted from that dam. Homesteaders bring<br />

wagonloads of grain and corn from miles around<br />

to our mill to be ground into flour and meal. The<br />

driveshaft is trimmed from a Lodgepole pine and the<br />

waterwheel and pit wheel are made from fir. Father<br />

has plans to bring in a steel driveshaft from back<br />

east once the Canadians finish building their railroad<br />

through British Columbia. And once we’ve saved<br />

enough money from selling our miller’s toll—the<br />

portion of flour that Father keeps as payment.<br />

Between the mill and the farm, we work hard from<br />

dawn to dusk. Father says that’s the price of freedom.<br />

Me, I count myself lucky that even if I wasn’t born<br />

free, I am free now. Out here in the frontier a man<br />

can be whoever he sets his mind to be. My friend Pete<br />

Harkness was born in the States—Minnesota, to be<br />

exact—and he never lets me forget it.<br />

“You’ll never be president,” Pete is fond of<br />

telling me.<br />

He’s referring to the fact that the United States<br />

Constitution requires that presidents be born on<br />

American soil—as though Pete, who had to repeat<br />

tenth grade, thinks that being born here makes him<br />

better fit for the job than I am. Pete and I are in the<br />

same grade now, but he’s sixteen and reminds me<br />

every chance he gets that he’s a year older than I am.<br />

Mam says not to mind him, that Pete hasn’t had the<br />

advantage of being raised in a God-fearing family the<br />

way I have, at least not since his mother died three<br />

years ago and his father took up with Mrs. Bell. I have<br />

never heard Mam gossip about Mrs. Bell the way<br />

some people do, but I can tell from the way Mam’s<br />

lips go tight at the mention of her name that she<br />

disapproves of her.<br />

This Sunday past, you could say fate took me by<br />

the hand. I was walking my brothers and sister the<br />

four miles from our property to Sunday school at the<br />

Presbyterian church in Nooksack when halfway there<br />

we saw smoke rising above the trees. That in itself<br />

wasn’t unusual—on a February morning, you’d be<br />

worried if you didn’t see smoke rising from a chimney.<br />

But this was different: thick and black.<br />

“That’s coming from Mr. Bell’s cabin,” said John.<br />

The Mr. Bell he was referring to was James Bell, an<br />

old-timer who ran a store out of his cabin, selling a<br />

few supplies to get by. He was also the lawful husband<br />

8 9

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

of the very same Mrs. Bell who is currently living<br />

under the roof of my friend Pete’s father.<br />

We hurried around the bend in the trail ahead to<br />

see what was the cause of the smoke. Flames were<br />

leaping above the trees by the time we started down<br />

the narrow path through a thicket of dogwood that<br />

led from the trail to the cabin. When we got to the<br />

clearing, the wood shack was going up like tinder.<br />

Fire was licking out of the windows of the front room,<br />

where Mr. Bell kept his dry goods for sale. If I’d let<br />

him, John—who is thirteen and a know-it-all—would<br />

have rushed right up to it. Will, a year younger than<br />

John and pretty much John’s shadow, would have been<br />

right behind him.<br />

“Mr. Bell?” I called from a safe distance, holding<br />

John and Will back.<br />

There was no answer, just the loud crack of<br />

blistering wood. I thought about running to the<br />

closest farmstead for help, the Breckenridges’, but it<br />

would have been a good twenty minutes to get there,<br />

and another twenty back.<br />

I tried again. “Mr. Bell!”<br />

“He can’t hear you!” said John.<br />

I had to admit John was right. The bursting and<br />

crackling of the fire was making too much noise. There<br />

was nothing to do but inch up and have a look inside<br />

that inferno.<br />

“You stay here with Annie,” I told Will. Annie is<br />

only nine, and I could see her eyes were wide with<br />

fright.<br />

John and I crept alongside the cabin toward<br />

the back, where the flames hadn’t caught hold yet,<br />

shielding ourselves from the heat. We peered through<br />

a window and saw Mr. Bell lying face down on the<br />

floor between the storeroom and the kitchen at the<br />

rear. A fog of smoke was quickly filling the space<br />

above him.<br />

“We got to get him out!” declared John.<br />

“Let’s hope he’s got a back door,” I yelled over the<br />

din, because it was obvious we were not going through<br />

the front way.<br />

We ran to the rear of the cabin and were relieved<br />

to see that there was a way into his kitchen. When we<br />

pushed open the door, smoke came rushing out at us.<br />

It stung our eyes and blinded us, but after a moment it<br />

cleared enough for us to see Mr. Bell lying there.<br />

“Mr. Bell!” I called again, but he wasn’t budging.<br />

The fire was traveling fast from the front room. We<br />

had to get him out of there.<br />

“Hold your breath!” I shouted to John.<br />

The two of us dashed inside. I suppose it paid to<br />

be brothers that day, because without having to plan<br />

it, we each grabbed hold of one of Mr. Bell’s arms and<br />

dragged him out of there, like his limbs were branches<br />

on a log we were lugging to reinforce our dam. He was<br />

heavy enough that even with two of us we made slow<br />

10 11

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

progress toward the back door. A loud bang from the<br />

front room sent the taste of fear up from my stomach<br />

into my throat. I looked up to see burning timbers<br />

falling, and daylight where the roof used to be. I<br />

glanced at John. If he was as scared as I was, he didn’t<br />

let it show. He just kept hauling Mr. Bell toward the<br />

door. I did what he did. Pretty soon we had Mr. Bell<br />

out on the grass and we were filling our lungs with<br />

good air.<br />

John was a sight—his face streaked with grime,<br />

his Sunday clothes covered in ash and soot—and I<br />

reckon I was, too. My first thought was that Mam<br />

would have our hides for ruining our Sunday best. But<br />

that thought was chased from my head when I looked<br />

down at Mr. Bell. He still hadn’t moved, and at a<br />

glance I saw the reason why—the back of his head was<br />

nothing but a bloody mess. John had gone pale. Annie<br />

and Will stood staring. Me, I felt my stomach rising.<br />

I’d chopped the head off many a chicken and watched<br />

the blood spurt, but this was different.<br />

“What happened to him?” Annie asked, her voice<br />

high and frightened.<br />

“Is he dead?” asked Will.<br />

I knelt down and rolled him over. His eyes were<br />

wide open. His skin was gray against the white of<br />

his beard, and I could count what teeth he had left<br />

through his gaping mouth. The first thought that came<br />

into my head was,<br />

“We got to fetch Doctor Thompson.”<br />

“What the hell for?” John huffed. “Can’t you see<br />

he’s a goner?!”<br />

“Don’t be cursing in front of Annie,” I told him.<br />

“He looks surprised,” she said.<br />

“You’d be surprised, too, if your head got bashed<br />

in,” said John.<br />

“How do you reckon it happened?” asked Will.<br />

The three of them were looking down at Mr. Bell<br />

with unseemly curiosity, considering how recently his<br />

spirit had departed this world. I found a horse blanket<br />

on the woodpile and threw it over him.<br />

“It’s not for us to say,” I told them. “We need to<br />

fetch the sheriff.”<br />

12 13

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

Chapter Two<br />

Mr. Bell’s cabin was a couple of miles from<br />

Nooksack. John and I argued about which one of us<br />

should go for Sheriff Leckie to tell him about the<br />

violent end that had befallen Mr. Bell, and which one<br />

should stay with Annie, who had begun to blub and<br />

complain at the prospect of being left behind with a<br />

dead body.<br />

“Stop crying,” John told her. “Nobody even liked<br />

the old coot.”<br />

“Leave her be,” I said.<br />

Annie buried her head in my chest, adding tears<br />

and snot to the streaks of grime on my jacket—and<br />

settling which one of us would be dispatched for<br />

the sheriff to deliver the biggest news that had ever<br />

happened in the Nooksack Valley.<br />

“All right, you go,” I told John. “Take Will with<br />

you. And run.”<br />

“I know to run!” John snarled back, needing the last<br />

word just like always.<br />

The four of us walked together down the path<br />

to the trail. Annie and I watched our brothers take<br />

off at top speed toward town until they were out of<br />

sight. Now that she was a sufficient distance from the<br />

burning cabin—and from the body lying under the<br />

blanket—Annie calmed down.<br />

“We should go home,” she said. “We should tell<br />

Father what happened.”<br />

Mam is expecting a new baby any minute, and<br />

Father had stayed home from church to help mind<br />

Isabel, who’s three. Father isn’t big on churchgoing<br />

and preachers, anyway. He says he doesn’t need a<br />

middleman between him and the Almighty. He’s<br />

independent minded, and that’s what attracted him<br />

to living in America in the first place. Mam’s the one<br />

who makes us kids go to Sunday school. And she<br />

says that since we made the move to the Washington<br />

Territory, Father’s taken up a little too much frontier<br />

spirit for his own good.<br />

“We should wait here,” I told Annie. “We found<br />

the body. We’re witnesses. Sheriff Leckie’s going to<br />

want to talk to us.”<br />

“John can tell him as good as you can.”<br />

So now my little sister was arguing with me, too. I<br />

was beginning to think I did not command adequate<br />

respect from my juniors.<br />

“You stay here,” I said, indicating a tree stump<br />

where she could sit down.<br />

“Where are you going?”<br />

14 15

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

“To investigate.”<br />

“Investigate what?”<br />

“To investigate what happened to poor Mr. Bell.”<br />

“John says nobody liked him.”<br />

“Just because a man isn’t liked doesn’t mean he<br />

deserved to die.”<br />

People say Mr. Bell was strange in the head,<br />

starting with the fact that he chose for some reason<br />

to build his shack on the edge of a swamp instead of<br />

on decent farmland. Maybe that’s why Mrs. Bell took<br />

their son, Jimmy, and left him. That, and because she’s<br />

half the old man’s age.<br />

“Why would he deserve to die?”<br />

“I just said he didn’t!”<br />

“You made it sound like somebody thought he did.”<br />

“Just sit there!” I ordered, and walked away into<br />

the dogwood patch before she could squabble any<br />

further.<br />

When I came out into the clearing, the heat from<br />

the cabin was enough to singe my hair. I gave the<br />

building a wide berth as I walked around it. The<br />

flames had pretty much eaten up the cabin inside and<br />

out and were making the leap to an open shed out<br />

back. I thought briefly about trying to save a wagon<br />

that was parked inside that shed, but the fire was<br />

moving too fast and with too much fury. As I watched<br />

the roof of the shed fall into the wagon’s bed, it<br />

dawned on me: Where was Mr. Bell’s horse?<br />

“Get away from there!”<br />

I spun around to see Mr. Osterman standing where<br />

the path opens from the dogwood into the clearing,<br />

motioning at me with his arm. Annie was standing<br />

beside him. Bill Osterman is the telegraph man for<br />

Nooksack. He is often to be seen riding the trail,<br />

checking the telegraph lines that follow it. He’s barely<br />

thirty, but he’s much respected hereabouts, for it’s the<br />

telegraph that keeps us settlers connected with the<br />

states back east, and California to the south. I’ve often<br />

thought that one day I would like to be a telegraph<br />

man, like him, living in a nice house in town and not<br />

having to wake up with the cows.<br />

“Come away from there, boy!” he yelled. “You’ll be<br />

burnt as well as roasted!”<br />

I obeyed him.<br />

“We found Mr. Bell!” I told him, coming toward<br />

him. To my surprise, my voice cracked as I said it and<br />

my throat felt tight—as if any minute I might cry<br />

like a girl. I turned away from him while I got hold of<br />

myself, pointing to the blanket-covered body lying in<br />

the grass. “He’s there.”<br />

Mr. Osterman went over and raised the blanket<br />

only long enough to take in the situation before<br />

dropping it and backing away. He’s a smart dresser<br />

compared to the farm men—maybe he didn’t want to<br />

get his nice clothes dirty.<br />

“You found him like this?” he asked. His face<br />

16 17

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

looked grim.<br />

“He was inside the cabin. My brother John and I<br />

pulled him out.”<br />

“And who might you be?”<br />

“George Gillies, sir.”<br />

He glanced over at Annie.<br />

“You Peter Gillies’s kids?”<br />

“Yes, sir. We were on our way to church. John and<br />

Will went ahead to fetch Sheriff Leckie.”<br />

He nodded. Then, “Church will still be there next<br />

Sunday. You should take your sister on home now, son.<br />

This isn’t a sight for a little girl.”<br />

Part of me knew he was right, but a bigger part of<br />

me wanted to stay put. I told him, “I have to wait for<br />

my brothers.”<br />

“I’ll wait here for them to come back with the<br />

sheriff, and I’ll send them home after you.”<br />

“I’d prefer to wait, if you don’t mind.”<br />

I don’t know where I found the gumption. Mr.<br />

Osterman stared at me in surprise for a long moment.<br />

I thought he was angry, but then he let out a laugh.<br />

“Well, Master Gillies, I can see you are a man who<br />

knows his own mind.” Then he became serious again.<br />

“Take your sister out by the trail, George. Give me a<br />

holler when you see the sheriff coming.”<br />

I knew better than to argue with him any further.<br />

But I believed it was my duty to inform him, “His<br />

horse is gone.”<br />

Mr. Osterman looked about Mr. Bell’s narrow strip<br />

of land, at the small paddock squeezed between the<br />

dogwood and the swamp.<br />

“So it is. Likely stolen by whoever did this to him,”<br />

he said.<br />

“You think somebody killed him?” He didn’t seem<br />

to hear me.<br />

“Go on now,” he said. “Look after your sister.”<br />

Annie and I waited by the trail like Mr. Osterman<br />

said. I kept my eyes fixed on the point where the trail<br />

disappeared into the woods ahead for the first sign of<br />

the sheriff. It was a mild day. The sun shone warm on<br />

my head. As the roar of the fire simmered down to the<br />

odd crackle, you could almost forget that something<br />

horrible had happened. But a picture of Mr. Bell’s<br />

smashed-in head flashed into my mind.<br />

Whoever did this to him, Mr. Osterman had said.<br />

Was he saying somebody had murdered Mr. Bell? If<br />

that was the case, the murderer could not be far away.<br />

It gave me the shivers just thinking about it, and made<br />

me keep a closer eye on Annie.<br />

Sheriff Leckie arrived on horseback a half hour<br />

later, without John and Will. The boys were following<br />

on foot. He had with him Bill Moultray, who runs<br />

the general store and livery stable at The Crossing,<br />

a shallow point in the Nooksack River where the<br />

Harkness ferry carries folks across. In a way, Mr.<br />

18 19

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

Bell was in competition with Mr. Moultray, selling<br />

provisions to the settlers, but Mr. Bell was like fly<br />

speck compared to Mr. Moultray, whose business<br />

is much bigger—supplying freight teams on the<br />

Whatcom Trail, the old gold rush route from the<br />

fifties that leads from the Washington Territory<br />

up to the Fraser River on the Canadian side of the<br />

International Border. Mr. Moultray is a big bug<br />

hereabouts, not just because he’s rich, but also because<br />

he’s been to Olympia many times, hobnobbing with<br />

the governor and the like.<br />

When I saw the pair of them coming, I ran to fetch<br />

Mr. Osterman as he had bid me to do. I found him<br />

using a long stick to pick through the hot embers that<br />

were pretty near all that was left of Mr. Bell’s cabin.<br />

“It’s the sheriff!” I called.<br />

He swung around to me fast as could be with a<br />

startled look on his face.<br />

“Didn’t your pa ever teach you not to sneak up on a<br />

person?” he said.<br />

By the time I got done apologizing and the two of<br />

us had walked back through the thicket to the trail,<br />

the sheriff and Mr. Moultray were pulling up their<br />

horses. Mr. Moultray is my father’s age, not young<br />

and handsome like Mr. Osterman, but he dresses<br />

even finer—never to be seen without his gold watch<br />

hanging from his waistcoat. Beside Mr. Moultray and<br />

Mr. Osterman, Sheriff Leckie looked like a character<br />

out of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in his dusty<br />

hat and long coat. He talks as slow as he moves, as<br />

though he’s worn out from a life spent in the saddle,<br />

facing down outlaws and Indians.<br />

“What have we got, Bill?” asked Sheriff Leckie,<br />

climbing down from his horse.<br />

“Looks like somebody fired a shotgun into Jim<br />

Bell’s head,” replied Mr. Osterman.<br />

Shot! Mr. Moultray looked as shocked as I was.<br />

“Who would do such a thing to a harmless old<br />

man?” he asked, dismounting.<br />

“I’ll tell you what,” said Mr. Osterman. “I got a bad<br />

feeling I may have put Jim Bell in harm’s way.”<br />

The sheriff looked up from where he and Mr.<br />

Moultray were tying their horses off to nearby trees.<br />

His eyes went narrow.<br />

“Why would you say that?” the sheriff asked.<br />

Mr. Osterman glanced over at Annie and me with<br />

the same look my father gets when he wants to say<br />

something to Mam that isn’t for our ears. Sheriff<br />

Leckie looked at us, too.<br />

“You the other Gillies kids?”<br />

“Yes, sir,” I said.<br />

“You’re the one who found the body?”<br />

I’ll admit I puffed up with pride to have the sheriff<br />

of Whatcom County ask me such a question.<br />

“Yes, sir,” I replied. “I am.”<br />

Sheriff Leckie turned to Mr. Osterman.<br />

20 21

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

“Let’s see what we got.”<br />

The remains of the cabin were smoldering now and<br />

the smoke stung my eyes as we stood in the clearing.<br />

Sheriff Leckie, Mr. Osterman, and Mr. Moultray<br />

rolled Mr. Bell’s body over to get a look at his bashedin<br />

head. They knelt there for a long time in the grass,<br />

talking amongst themselves. They made Annie and<br />

me keep our distance, so it was hard to make out what<br />

they were saying, but I caught bits and pieces.<br />

“… crazy old fool wouldn’t keep a gun to<br />

defend himself …”<br />

“… too trusting … always taking in strays …”<br />

It was curious the way they blamed Mr. Bell for<br />

getting himself murdered. Still, I knew what they were<br />

saying. Many a time when we were passing by Mr.<br />

Bell’s cabin on the way to or from school, the old man<br />

would be waiting out on the trail to offer us children a<br />

sweet or a drink of water. But there were things about<br />

him—his yellow teeth and sour breath, the smell of<br />

his unwashed clothes, the way he laughed like he had<br />

some secret joke—that made me make excuses and get<br />

my brothers and sister away as fast as I could.<br />

I listened some more.<br />

“… got him in the back of the head …”<br />

“… must have turned his back to go for<br />

something …”<br />

“… or just caught unawares …”<br />

Then, from Mr. Osterman, “You think the Indian<br />

could have done this?”<br />

An Indian! The thought of an Indian murdering<br />

a white settler was enough to send a tremor through<br />

every one of us standing in that clearing. If the<br />

Indians thought they could get away with killing<br />

one of us, they were just as liable to get the notion of<br />

starting an all-out war, aimed at driving every man,<br />

woman and child out of our homes.<br />

When we crossed the prairie by wagon train six<br />

years ago, the old-timers told us hair-raising tales<br />

about how the savages were known to attack the<br />

trains and wipe out whole families—innocent people<br />

who wanted nothing more than to create new homes<br />

for themselves out of the wilderness. Settlers have<br />

only been in these parts for barely longer than I’ve<br />

been alive, and the Indians outnumber us by a long<br />

shot. Before we arrived, all they did was fish and<br />

hunt. That left a lot of land unspoken for, and in<br />

the past twenty years lumbermen and miners and<br />

homesteaders have been pleased to claim that land<br />

as their own. Wouldn’t you know that the Indians<br />

would then turn around and complain that the<br />

territory belongs to them and we’ve got no business<br />

being here, even though they weren’t using the land<br />

for anything much to speak of.<br />

It’s put into folks’ heads from the cradle that if a<br />

white man lets an Indian get the upper hand, the next<br />

thing you know your scalp is as likely as not to be<br />

22 23

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

hanging off of his belt. We settlers are ever mindful of<br />

the fact that barely eight years ago Crazy Horse and<br />

his warriors massacred General Custer and his men at<br />

the Little Big Horn River, due east of us in Montana.<br />

The worry that even the friendly Indians might turn<br />

against us is enough to make every homesteader bolt<br />

the door at night and sleep with his rifle and an ax<br />

beside his bed, including my father. If an Indian killed<br />

Mr. Bell, none of us could sleep easy.<br />

John and Will arrived back, winded from running<br />

the whole distance. “What’s going on?” John asked,<br />

annoyed that he was missing out on something.<br />

“They think an Indian might have done it,” I<br />

told him.<br />

“What Indian?”<br />

“Just pay attention and maybe you’ll find out.”<br />

He was irking me, making me miss out on<br />

important details. The blanket was back over Mr. Bell’s<br />

body now, and the men were standing to continue<br />

their discussion, making it easier to hear them.<br />

“I put out the word that I was looking for<br />

somebody to fix poles for me, and this morning Louie<br />

Sam shows up,” Mr. Osterman was saying. “I could<br />

tell he was a bad type the minute I laid eyes on him,<br />

but I started walking the line with him down this way,<br />

pointing out what needed repairing. He was too slowwitted<br />

to catch on to what I was trying to get across<br />

to him. I’ll tell you, he was hot-headed enough to<br />

send smoke signals through his ears when I told him I<br />

couldn’t use him and sent him away.”<br />

“And this was just this morning?”<br />

“That’s correct, Sheriff. He came by the telegraph<br />

office early for a Sunday, maybe nine o’clock.”<br />

The sheriff checked his pocket watch.<br />

“It’s now a quarter past eleven.”<br />

“The timing’s right. I left him on the trail not far<br />

from here a little more than an hour ago. I kept on<br />

going down the line. I figured Louie Sam headed back<br />

into town. But maybe he didn’t. Maybe he found Jim<br />

Bell’s place.”<br />

“I know Louie Sam.” It was Bill Moultray talking<br />

now. “He’s a Sumas, from the Canadian side. And<br />

I know his old man, too. They call him Mesatche<br />

Jack Sam.”<br />

“ ‘Mean,’” said Sheriff Leckie, translating from<br />

Chinook, the trade jargon used by the various Indian<br />

bands in this area to make themselves understood to<br />

each other, and to us whites.<br />

“You got it. Mean Jack’s in jail up in New<br />

Westminster for murder.”<br />

This gave all three of them pause, until Mr.<br />

Osterman stated what we were all thinking: “The<br />

apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.”<br />

If the father was a murdering Indian, so was the son<br />

likely to be. We had ourselves a suspect in the murder<br />

of Mr. James Bell, and his name was Louie Sam.<br />

24 25

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

Chapter Three<br />

John and I agreed that we should send Annie<br />

home with Will, and that the two of us should stay at<br />

Mr. Bell’s place in case the sheriff had more questions<br />

for us. But the men seemed to forget we were there.<br />

They found long sticks and poked at the charred<br />

remains of the cabin, which were still too hot to<br />

touch. Mr. Osterman used the end of his stick to pick<br />

up a blackened jug from what was left of Mr. Bell’s<br />

merchandise.<br />

“My bet is Jim Bell caught that Indian helping<br />

himself to his goods,” he said.<br />

“Hard to tell,” replied Sheriff Leckie, flipping<br />

through some tin cans that had exploded in the heat.<br />

“Who’s to say what’s missing?”<br />

“I found something!” called Mr. Moultray from the<br />

kitchen end of the ruins.<br />

We all turned to see Mr. Moultray using his thick<br />

boots to kick a fire-warped metal box out of the ashes.<br />

It sprang open, spilling a fortune in gold coins onto the<br />

grass! The sheriff let a whistle out between his teeth.<br />

“It don’t look like no robbery to me,” he said.<br />

Mr. Osterman knelt down to count the coins, but<br />

the first one burned him when he tried to pick it up.<br />

“Goddamit!” he blasphemed, blowing on his fingers.<br />

“There must be five hundred dollars there,” said<br />

the sheriff.<br />

“Louie Sam missed out on the big prize,” remarked<br />

Mr. Moultray.<br />

“But he might have taken Mr. Bell’s horse,” I said.<br />

The men turned to me and John. They seemed<br />

surprised to find us still there. The sheriff rubbed<br />

his chin.<br />

“Nobody’s seen his horse this morning?” he asked.<br />

“No, sir,” I replied. “It was gone when we got here.”<br />

“If that Indian’s on horseback, he could be ten<br />

miles away by now,” said Mr. Moultray. “All the way to<br />

the border. Assuming he’s heading for his tribe on the<br />

Canadian side.”<br />

“So he’s a horse thief as well as a murderer,” was all<br />

that Mr. Osterman had to add.<br />

But just after noon, Robert Breckenridge, a<br />

neighbor from a couple of miles away, arrived leading<br />

a stray he said had turned up on his land and which<br />

he recognized as belonging to Mr. Bell. He had come<br />

by only meaning to return the horse, and was shocked<br />

by the sight of the cabin—shocked still further when<br />

the men told him what had befallen Mr. Bell. Mr.<br />

26 27

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

Breckenridge related how just the day before he had<br />

seen a lone Indian lurking around near his spread,<br />

carrying a rifle, who claimed when challenged that<br />

he was hunting game. The men agreed that it stood<br />

to reason that the Indian Mr. Breckenridge saw could<br />

well have been Louie Sam, and that the rifle he was<br />

carrying was very likely the murder weapon.<br />

Next thing you know Father arrived on Mae, our<br />

mare, telling John and me to go home. He’d heard<br />

enough from Will and Annie to make him come<br />

fetch us. I think he mostly came out of curiosity,<br />

though, because a minute later he was caught up in<br />

the mystery as Sheriff Leckie and Mr. Moultray told<br />

the whole story all over again. On hearing it a second<br />

time—with Mr. Breckenridge’s additions—it was<br />

plain as day that Louie Sam was the culprit, even if<br />

he could no longer be called a horse thief. Murdering<br />

an innocent white man in cold blood was just like<br />

something a bad Indian would do.<br />

At that point, Mr. Osterman gave a holler. He had<br />

been checking around Mr. Bell’s property and had<br />

found tracks leading into the swamp. Sheriff Leckie<br />

told us all to stand back while he took a look, but even<br />

at a distance I could make out some faint dents in the<br />

grass that could easily have been made by moccasins.<br />

At the place where the footprints reached the swamp<br />

there were trampled rushes—as though a body had<br />

burst through them at a run.<br />

“Louie Sam must have escaped this way,” declared<br />

Mr. Osterman.<br />

“Now hold on,” said Sheriff Leckie. “A deer could<br />

have made this track as well as an Indian.”<br />

“But Sheriff,” I blurted, “that renegade could be<br />

getting away!”<br />

Father turned toward me, reminded of my presence.<br />

“I thought I told you to go home.”<br />

“Don’t be cross with the boy, Mr. Gillies,” said Mr.<br />

Osterman. “George has been a real help today.”<br />

“So have I!” piped up John.<br />

“Quiet, both of you,” said Father, “or I’ll send you<br />

on your way right now.” Which John and I took to<br />

understand that we would be allowed to stay as long<br />

as we remembered our place.<br />

Sheriff Leckie had been quietly thinking.<br />

“That Indian has had a couple of hours to clear<br />

out of here. He’ll be headed north. Once he’s crossed<br />

the border, it’s up to the Canadians what they do<br />

with him.”<br />

That made Mr. Breckenridge, a small man who<br />

makes up with spitfire what he lacks in height and<br />

breadth, hot under the collar.<br />

“Jim Bell is one of us!” he said. “He’s a Nooksack<br />

Valley man, and that Indian ought to pay for what he<br />

done in the Nooksack Valley!”<br />

“I won’t argue that with you, Bob,” the sheriff<br />

replied, his words slow as molasses. “But we’ve got our<br />

28 29

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

laws and the Canadians have got theirs.”<br />

“If we start north now, we can catch him before<br />

he leaves the Territory,” said Mr. Osterman. “If we let<br />

him get cross the border, there’s no saying whether the<br />

Canadians will hand him over.”<br />

Mr. Breckenridge agreed. “You got to stop that<br />

savage before he gets away, Sheriff.”<br />

The sheriff pulled at his chin. “I suppose I best<br />

get started.”<br />

“I’ll come with you,” said Mr. Breckenridge. “You<br />

shouldn’t face that red-skinned dog alone.”<br />

It was agreed that Mr. Breckenridge would go<br />

with Sheriff Leckie. The rest of us stayed behind to<br />

find out where the trail into the swamp led, with Mr.<br />

Osterman in the lead. It was hard going, trying to<br />

find bits of solid ground to set our boots upon. After<br />

five minutes my feet were wet and cold, but I wasn’t<br />

about to complain about it for fear of looking like I<br />

couldn’t keep up with the men. I glanced behind me<br />

to John to try to make out whether he was in the same<br />

discomfort as me. His pig-headed look told me that<br />

he was.<br />

It was clever of that Indian to escape through the<br />

swamp, which swallowed up his footprints the same<br />

way it tried to swallow our boots. But Mr. Osterman<br />

did a good job of reading what signs as there were,<br />

finding a broken branch here, and a handkerchief<br />

stuck to a bramble there. We came across some cans<br />

of beans and bully beef that must have come from<br />

Mr. Bell’s store, as though Louie Sam in his haste<br />

had dropped them. Strangest of all was an old pair of<br />

suspenders we found caught in some brambles. As we<br />

plunged onward, the men began to talk about what<br />

was on everyone’s mind.<br />

“Once the Nooksack hear about this, there’s bound<br />

to be more trouble,” said Mr. Moultray.<br />

The Nooksack is the name of the local Indians<br />

on our side of the border, from which the river and<br />

our town took their names. On the Canadian side,<br />

it’s the Sumas tribe. To hear the Indians tell it, they<br />

were all one big happy family until the International<br />

Border cut right through their hunting grounds<br />

twenty-five years ago, dividing them up. According<br />

to Mr. Breckenridge, who Father says considers<br />

himself to be an expert on just about everything, they<br />

still get together for wild heathen shindigs they call<br />

potlatches. Even though Louie Sam was a Sumas<br />

from the Canadian side, the worry was that he would<br />

go boasting to his cousins on the American side<br />

that he killed a white man. The Nooksack have been<br />

rumbling for years about this being their land. If they<br />

got the notion that getting rid of us settlers was as<br />

simple as shooting us like dogs, we could wind up<br />

with a full-scale uprising on our hands—just like what<br />

happened in Oregon and the Dakotas until the U.S.<br />

Army showed those Indians who was boss. The trouble<br />

30 31

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

was, the U.S. Army was nowhere in sight, the nearest<br />

outpost being three hundred miles south of us at Fort<br />

Walla Walla. The Indians of the Nooksack Valley<br />

knew we were pretty much defenseless, and that they<br />

had us outnumbered.<br />

“We didn’t have this kind of trouble when Bill<br />

Hampton was alive,” Father remarked.<br />

Mr. Hampton was the ferryman at The Crossing<br />

before he drowned and my friend Pete’s father, Dave<br />

Harkness, took over. “Bill had a knack for talking to<br />

the Nooksack. They listened to him.”<br />

Mr. Osterman let out a hard laugh, obviously not<br />

sharing Father’s good opinion of Mr. Hampton.<br />

“That’s because he was shacked up with one of their<br />

women and had himself a couple of Indian kids.” He<br />

was talking about Agnes, Mr. Hampton’s Indian wife,<br />

who lives near us on Sumas Creek with her two halfbreed<br />

sons. He added, “We got to make an example of<br />

Louie Sam before the Nooksack go getting ideas.”<br />

“No question about that,” Father agreed.<br />

“Let’s see what the sheriff has to say when he gets<br />

back,” Mr. Moultray told them.<br />

He was a natural leader, Mr. Moultray—cool and<br />

always thinking. He was the one leading the talk in<br />

our corner of the Washington Territory about pressing<br />

the Union to make us a full state with our own laws,<br />

and not just a territory ruled by the president from<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

We reached a big old log that was sticking up out<br />

of the swamp at an angle and climbed up on it. On<br />

the other side of it, we could see sunken footprints<br />

where Louie Sam had made a long jump off the log<br />

into the bog. From there the bush got thicker and<br />

the trail petered out. The men decided that there was<br />

no point continuing. If Louie Sam was going to be<br />

caught, it was up to the sheriff to do it.<br />

We returned to Mr. Bell’s burned-out cabin. The<br />

ruins were cooler now. It was easier to pick through<br />

the remains, but there was nothing much left. It<br />

seemed Mr. Bell didn’t own much to speak of, even<br />

before the fire turned it all to ash. Nothing but the five<br />

hundred dollars in gold he had in that strong box.<br />

“I’ll keep it in the safe at my store until it’s decided<br />

what’s to be done with it,” volunteered Mr. Moultray.<br />

“What about the body?” asked Father.<br />

“May as well bring him back to my place,” said Mr.<br />

Moultray. “He’ll keep in my shed until he’s buried. His<br />

horse can stay in my stable until somebody decides<br />

who gets him.”<br />

Father remarked, “I suppose somebody needs to tell<br />

Mrs. Bell what happened.”<br />

The men all fell silent at that. Nobody was stepping<br />

up to volunteer for that particular detail. The situation<br />

was complicated, what with Mrs. Bell having up and<br />

left Mr. Bell a year ago to go live with Pete’s pa.<br />

32 33

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

Father remembered something about Mr. Osterman.<br />

“Your wife Maggie is Dave Harkness’s sister,<br />

isn’t she?”<br />

“That she is,” he replied.<br />

Mr. Moultray saw what Father was driving at and<br />

finished his thought.<br />

“That’s practically family,” he said to Mr. Osterman.<br />

“It’s only fitting that you should be the one to tell<br />

Mrs. Bell.” He added by way of lessening the weight<br />

of the duty, “I don’t reckon she’ll be too sorrowful.”<br />

There was another long silence. From the way<br />

Father glanced at John and me, I got the feeling that<br />

more would have been said on the matter if we boys<br />

had not been present.<br />

Chapter Four<br />

It turned out that Sheriff Leckie and Robert<br />

Breckenridge didn’t make it to Canada on Sunday<br />

afternoon. They got stopped by the discovery of a new<br />

witness—who turned out to be none other than Pete<br />

Harkness. Outside the schoolhouse at lunchtime on<br />

Monday, I got the full story from Pete.<br />

“I was coming back from Lynden—”<br />

“What were you doing way over there?” I asked<br />

him. Lynden is a good five miles west of Nooksack.<br />

“I was running an errand for my pa. Stop<br />

interrupting!”<br />

Pete likes to hear himself talk. He may not be the<br />

smartest boy in school, but I know from my little<br />

sister Annie that all the girls in the classroom—from<br />

the first grade on up—think he’s handsome with<br />

his blue eyes and wavy hair. He’s tall and broadshouldered,<br />

and has a way of believing that his good<br />

looks mean he’s always right.<br />

“So I was heading along the road from Lynden<br />

back home to The Crossing,” he continued, “when I<br />

34 35

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

saw Louie Sam coming toward me, walking in the<br />

other direction. Let me tell you, the look on that<br />

Indian’s face struck me with terror—so dark was it and<br />

filled with evil. There was murder in his eyes.”<br />

“Did you see the rifle that he used to kill Mr. Bell?”<br />

“Damn right, I did! Of course, I didn’t know at the<br />

time that he used it to murder Mr. Bell.”<br />

Tom Breckenridge came over and joined us.<br />

“Pete saw Louie Sam yesterday,” I told him,<br />

“walking along the Lynden road.”<br />

“If I’d seen him,” Tom replied, “he wouldn’t be<br />

walking no more.”<br />

He spit in the dirt. Tom is Pete’s age, but small and<br />

wiry like his father. And—like his father—Tom is full<br />

of tough talk trying to make up for his size. Ignoring<br />

his bluster, I turned my attention back to Pete.<br />

“So what happened next?”<br />

“When I got to The Crossing, Uncle Bill was there,<br />

telling Pa that Mr. Bell was dead,” Pete said.<br />

“How did Mrs. Bell take the news?” I asked.<br />

“Why should I care?” proclaimed Pete.<br />

I should have known better than to ask. Pete has no<br />

fondness for his more-or-less stepmother, Mrs. Bell,<br />

nor for her son Jimmy, who’s living under Pete’s roof<br />

now like they’re supposed to be brothers.<br />

“Anyway,” he went on, “when I told Pa about seeing<br />

the evil look on that redskin, he said that I had to<br />

tell Sheriff Leckie what I saw right away. He even<br />

let me saddle up Star. I headed for the sheriff ’s office<br />

in Nooksack at a gallop, and got there just in time—<br />

because the sheriff and your pa,” he said, nodding to<br />

Tom, “were just about to set off north in search of<br />

Louie Sam.”<br />

“And the whole time, Louie Sam was heading west,<br />

on the Lynden road!”<br />

“Exactly. If it hadn’t been for me coming across<br />

him like that, they would have headed off on a wild<br />

goose chase to end all. As it was, Louie Sam managed<br />

to hide himself among a bunch of Nooksack in a camp<br />

they got near Lynden.”<br />

“So his tillicums took him in,” I remarked.<br />

That’s more Chinook lingo: tillicum means friend.<br />

“Sheriff Leckie tried to talk their chief into<br />

handing him over, but the chief said they hadn’t<br />

seen him.”<br />

“Lying Indians!” declared Tom.<br />

“Is there another kind?” replied Pete. “The sheriff<br />

said the chief had twenty or more braves with him,<br />

so there was nothing he could do but wait and hope<br />

that Louie Sam might make a break for it. Finally, he<br />

reckoned there was no point in waiting any longer.<br />

That Indian could have slipped away into the forest<br />

any time he wanted.”<br />

“Heading for his people north of the border,” I<br />

ventured to guess.<br />

“That’s what the sheriff thinks,” said Pete. “He<br />

36 37

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

and Tom’s pa headed up the trail for Canada this<br />

morning.”<br />

“Tell me something I don’t know,” said Tom.<br />

Pete’s account of seeing Louie Sam clinched it.<br />

If anybody had had doubts about that Indian’s guilt<br />

before, it was impossible to deny it now. The way<br />

everybody had it figured, Louie Sam must have come<br />

across Mr. Bell’s cabin shortly after his falling out<br />

with Mr. Osterman and decided to help himself to<br />

the supplies within. Given the temper on that Indian,<br />

it’s no stretch to imagine that the slightest complaint<br />

on the matter from Mr. Bell would have sent him on<br />

the rampage. So he waited until Mr. Bell’s back was<br />

turned and he let him have it. But, on the other hand,<br />

people said Mr. Bell would share a meal with anybody<br />

passing by, so why would he have denied a few cans<br />

of beans to an Indian who was holding a rifle? Why<br />

would he have risked his life for that? I voiced all of<br />

this to Pete.<br />

“You think too much,” was his reply. “Louie Sam<br />

killed Mr. Bell. That’s all you got to know.”<br />

“How’s Jimmy?” I asked.<br />

“How should I know?” Pete snapped.<br />

“It’s his pa that’s dead,” I said.<br />

Jimmy Bell is my brother John’s age and I don’t<br />

know him well, but I couldn’t help but feel sorry for<br />

him—especially since it mustn’t be easy for him, with<br />

his mother taking him away from his father to go live<br />

with the Harknesses.<br />

“Jimmy hated his pa,” replied Pete.<br />

“Why?”<br />

“Why do you ask so many stupid questions, George<br />

Gillies?”<br />

With that, Pete went off to join a ball game a few<br />

of the boys had started up in the field behind the<br />

school. My brother John was one of those boys, and so<br />

was Jimmy Bell. Jimmy was a quiet type, plump and<br />

big for his age—not really one to stand out at sports<br />

or in school. I watched him take his turn stepping up<br />

to bat, swinging, missing an easy ball—cursing. If he<br />

was sad about his pa it didn’t show. So maybe Pete<br />

was right. Maybe he did hate his father—or at least<br />

had no warm feelings for him. But then I thought,<br />

maybe Jimmy was feeling more angry than sad about<br />

what happened. I guessed that I might feel that way,<br />

too, if it was my father who had been murdered in<br />

cold blood.<br />

Mr. Breckenridge came back from Canada that<br />

very afternoon. We heard this news from our neighbor,<br />

Mr. Pratt, who came to our mill late in the day. He<br />

heard it from Mr. Hopkins who works at the new<br />

hotel in town—who had been at The Crossing when<br />

Mr. Breckenridge arrived at Bill Moultray’s store with<br />

the tale of his journey. News travels up and down the<br />

38 39

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

valley so fast, it’s almost like the telegraph line.<br />

“The sheriff and Bob Breckenridge went to see<br />

the Canadian justice of the peace in Sumas, a Mr.<br />

Campbell,” said Mr. Pratt, who’s a natural storyteller<br />

and plays the fiddle when there’s a dance in town.<br />

Like Father, he’s a Scot by birth. “The justice listened<br />

to all the evidence Sheriff Leckie presented and<br />

agreed that Louie Sam was the likely culprit. It<br />

turns out that Justice Campbell’s the one who put<br />

Louie Sam’s old man in jail for murder, so it came as<br />

no surprise to him that the son had followed in his<br />

father’s footsteps.”<br />

“What’s he planning to do about it?” asked Father<br />

as he poured a sack of Mr. Pratt’s wheat into the<br />

hopper, getting ready to grind it.<br />

“He issued a warrant for Louie Sam’s arrest. But,<br />

the way Bob tells it, the sheriff didn’t altogether trust<br />

this Campbell fellow. The Canadians have different<br />

ways, different laws. So the sheriff talked Campbell<br />

into letting him ride with him to take Louie Sam into<br />

custody, to make sure justice is served. Bob and the<br />

sheriff parted ways at that point, and Bob came back<br />

here to spread the word.”<br />

“And this Justice Campbell expects the Sumas to<br />

hand Louie Sam over just like that? Because he has<br />

a warrant?” Father’s eyebrow was cocked, meaning he<br />

thought this was a daft notion.<br />

“Aye, that’s the question, Peter,” replied Mr. Pratt,<br />

with his own knowing look. “That’s the question.”<br />

Before leaving, Mr. Pratt also told us that plans<br />

had been made for Mr. Bell’s funeral. Those who were<br />

interested in paying their respects were to meet at the<br />

Hausers’ cabin on Wednesday. Judging by the mood in<br />

the valley, Mr. Pratt expected to see every man in the<br />

district there, ready to show the local Indians by force<br />

of numbers that they would not let the murder of a<br />

white man go unnoticed, or unpunished.<br />

40 41

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

Chapter Five<br />

On Wednesday morning, the day of Mr. Bell’s<br />

funeral, my mother and father were arguing. There<br />

were no raised voices—that isn’t Mam’s way. But<br />

when she is displeased, you know it. I could tell just<br />

by looking at her when Father and I came in from<br />

milking that something was eating at her. Mam was<br />

short-tempered as she tried dishing up breakfast,<br />

hampered by the big roundness of her middle—that<br />

out of delicacy we boys were not supposed to mention.<br />

Finally, Father told Mam to sit down and let Annie<br />

do the serving. In that, she obeyed him. But her<br />

mouth was still tight as a drum as she helped Isabel<br />

with her porridge.<br />

“Anna, it’s the man’s funeral,” Father said out of<br />

the blue, as though picking up on a discussion he and<br />

Mam had been having earlier.<br />

“I have no argument with you going to show Mr.<br />

Bell his due. It’s this foolish talk I can’t abide.”<br />

I was curious about what talk she was referring to.<br />

“You do not appreciate the seriousness of the<br />

matter,” replied Father, using his serious voice to prove<br />

the point.<br />

“I get along just fine with the Indians,” Mam said.<br />

“When do you ever have business with the<br />

Indians?”<br />

“Agnes Hampton often brings me berries in<br />

exchange for a few eggs. Or one of her boys will bring<br />

me a hare, or a brace of quail.”<br />

“That squaw was never Mrs. Hampton,” Father<br />

replied.<br />

From the way he said it, there was a meaning<br />

behind the words that he did not intend for us<br />

children to grasp. But being more experienced in the<br />

world than my brothers and sisters, I knew what he<br />

was getting at—that the Hamptons had never been<br />

properly married. Mam was silenced for a moment by<br />

that remark, though not for long.<br />

“It seems some folks are more easily forgiven on<br />

that account than others.”<br />

Now she was talking about Pete’s father and Mrs.<br />

Bell, who also lived as man and wife without the<br />

benefit of a preacher.<br />

Father came back with, “There’s sinning, and then<br />

there’s sinning.”<br />

I wasn’t at all sure what Father meant by that, but<br />

Mam seemed to understand him just fine.<br />

“It’s not those boys’ fault they were born halfbreeds,”<br />

she said. “And just because there’s one bad<br />

42 43

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

Indian, that doesn’t mean you men have cause to tar<br />

all the rest of them with the same brush.”<br />

At that, Father put his foot down.<br />

“I’ll thank you to leave men’s business to the men.<br />

This conversation is hereby over.”<br />

Mam’s mouth was tighter than ever.<br />

I caught up with Father as he was heading from<br />

our cabin down to the mill, our dog Gypsy following<br />

us and barking into the woods surrounding the path.<br />

Something had her excited. I hoped it wasn’t a bear or<br />

a cougar.<br />

“Father?”<br />

“What is it, George?”<br />

“I thought you liked Mr. Hampton.”<br />

“I liked him just fine.”<br />

“Then why do you think he was a sinner? I mean, a<br />

worse sinner than Mr. Harkness?”<br />

Father rubbed his chin with the flat of his hand.<br />

“George,” he said, “you’re almost a man now. You<br />

need to understand the way things work. God in his<br />

wisdom created different types of people. That’s the<br />

way he wanted it. So when those different types of<br />

people …” He stopped himself, then started again.<br />

“When it comes to marrying and raising bairns, those<br />

types are meant to stick to their own kind. Are you<br />

following me?”<br />

I was not, in fact, following him too well. But I was<br />

a man, or almost a man. Father had just said so. And a<br />

man has to understand these things.<br />

“Sure I do,” I said.<br />

“Good. Now get yourself to school and put some<br />

learning in that head of yours.”<br />

The settlers built the one-room schoolhouse<br />

on the western edge of Nooksack a few years ago. It<br />

takes a good hour of walking for John, Will, Annie,<br />

and me to get there, following the trail that leads into<br />

town—the one that passes by Mr. Bell’s cabin. Even<br />

three days later there’s a bitter smell in the air from<br />

the fire as we go by. Every morning since it happened,<br />

John and Will had wanted to linger at the Bell place<br />

and explore. I had to bark at them to hurry along,<br />

lest we were late for school and Miss Carmichael, the<br />

schoolma’am, kept us in at recess as punishment.<br />

Jimmy Bell wasn’t at school Wednesday morning.<br />

Neither was Pete Harkness. Miss Carmichael had to<br />

yell at us kids to pay attention. Nobody had a mind for<br />

grammar or sums. All anybody wanted to talk about<br />

was the funeral, and whether Jimmy and Pete would<br />

be there. And whether Mrs. Bell would show up. I’ve<br />

seen Annette Bell in town, and a few times when I<br />

was over at The Crossing to visit Pete. She is young—<br />

younger than Mam—and she comes from Australia,<br />

which makes her a curiosity. Folks around here come<br />

from Great Britain and Canada and various states, but<br />

44 45

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

she’s the only one from Australia. Everybody knows<br />

that they send convicts to Australia.<br />

It’s hard to picture Mrs. Bell being in love with<br />

old Mr. Bell. Pete’s father, on the other hand, is tall<br />

and strong and broad-shouldered from pulling the<br />

cable ferry that spans the Nooksack River—the sort of<br />

man that some women, Mam is willing to grant, find<br />

handsome. It seems the Harkness men are lucky that<br />

way.<br />

Miss Carmichael told the senior class to take out<br />

our slates and do the algebra she’d written on the<br />

blackboard. Over the squeaking of chalk, I heard<br />

Abigail Stevens whisper to Kitty Pratt, “Mrs. Bell only<br />

married Mr. Bell for his money.”<br />

Abigail is sixteen and—I supposed—knows about<br />

such things. I remembered the five hundred dollars<br />

in gold coin that Sheriff Leckie found in Mr. Bell’s<br />

cabin, and thought that maybe she was right.<br />

At noon, Miss Carmichael—who suffers from<br />

nervous headaches—told us not to come back to<br />

school after the dinner break. I started on my way<br />

home with John, Will, and Annie, but it wasn’t long<br />

before a different destination came to mind. The<br />

funeral was due to get started at one o’clock. All the<br />

men of the Nooksack Valley would be there, and I<br />

intended to be there, too. I told John to walk on home<br />

with the younger kids. But being stubborn by nature,<br />

John was not about to be left behind. So Will wound<br />

up walking Annie home, while John and I headed over<br />

to the Hauser place.<br />

“Why is the funeral happening at the Hausers’?” I<br />

pondered as we walked. “Why not at church?”<br />

Nooksack has two churches to choose from, the<br />

Presbyterian and the Methodist. We Gillies are<br />

Presbyterians, being Scots.<br />

“Don’t you know that old man Bell was godless?”<br />

replied John.<br />

“Is that what Jimmy told you?”<br />

“Jimmy says he was a downright heathen. Worse<br />

than an Indian, because he should know better.”<br />

“Is that why Jimmy and his mam left him?”<br />

“I don’t know why they left,” said John.<br />

“It’s like there were two different Mr. Bells,”<br />

I mused. “Some folks say he was a nice old man,<br />

generous to a fault. Others say he was strange in the<br />

head. It’s sad his own son doesn’t care that he’s dead.”<br />

John had no comment on that.<br />

The Hausers’ farm is on the opposite side of<br />

Nooksack from our place—south of town instead of<br />

north. It’s just a stone’s throw from The Crossing,<br />

where Bill Moultray has his store and Dave Harkness<br />

has his ferry. When John and I got there, the long<br />

track leading up to the cabin was clogged with<br />

wagons. Dozens of horses were tethered to bushes<br />

46 47

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

and to the split-rail fence surrounding a small corral.<br />

Still more were inside the corral, poking their noses<br />

through the fence to snatch mouthfuls of clover. I<br />

recognized Star, the Harknesses’ gelding. Up closer<br />

to the cabin, John and I came across Mae, tied by her<br />

reins to a cedar sapling. When John spoke her name,<br />

she raised her head and gave us a funny look, like she<br />

was wondering what in heck we were doing there.<br />

Then she went back to cropping grass.<br />

Several men were standing outside on the veranda,<br />

smoking and talking quietly. Among them were Bill<br />

Osterman, the telegraph man who’d led our search<br />

through the swamp, and Tom Breckenridge’s father,<br />

who had gone up north with Sheriff Leckie. Dave<br />

Harkness was with them, too. Mr. Osterman’s face was<br />

grim.<br />

“Are we going to allow the Canadians to interfere<br />

in our business?” he was saying. “Does a murdering<br />

Indian deserve a trial, same as a civilized man?”<br />

“He most certainly does not!” declared Mr.<br />

Breckenridge.<br />

Bert Hopkins, a shorty in specs who runs the new<br />

Nooksack Hotel, spoke up.<br />

“What can we do about it? The Canadians have got<br />

him in custody by now.”<br />

“We got a jail right here in town that would hold<br />

him just fine,” said Mr. Harkness.<br />

“That’s what I’m thinking,” agreed Mr. Osterman.<br />

At that moment, my friend Pete came outside.<br />

“Pa, Uncle Bill,” he said, Mr. Osterman being<br />

married to his auntie, “they’re ready to start.”<br />

The men exchanged more grim looks, and filed into<br />

the cabin.<br />

“Pete!” I called.<br />

He turned, frowning at the sight of John and me as<br />

we reached the veranda.<br />

“This is no place for kids,” he said.<br />

That made my blood boil. Sometimes Pete acts like<br />

such a big bug, just because he’s got a year’s head start<br />

on me.<br />

“We’re the ones who found the body,” John shot<br />

back. “We got a right to be here.”<br />

“There’s serious talk going on inside,” Pete told us.<br />

“If you can hear it, I can hear it,” I said.<br />

“And me,” John was quick to add.<br />

“I’m not wasting my time arguing with you two,”<br />

Pete replied, and went into the cabin.<br />

John and I went right in after him.<br />

The cabin was so packed with men that it was easy<br />

for John and me not to be noticed by Father, who was<br />

on the other side of the room. Mrs. Bell was not there,<br />

but her son Jimmy was. A wooden box containing<br />

Mr. Bell was propped up on chairs at one end of the<br />

room. Jimmy stood near the casket, wearing a sullen<br />

expression, like he didn’t want to be there. John and<br />

48 49

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

I listened while several of the men said nice things<br />

about Mr. Bell. Bill Moultray gave a speech first, then<br />

Mr. Breckenridge spoke, and Mr. Hauser, but neither<br />

Jimmy nor Mr. Harkness had anything to say about<br />

the dead man.<br />

When Mr. Osterman got up to speak, he took a<br />

different tone. He didn’t talk about what a good man<br />

Mr. Bell was. He talked about what an outrage it was<br />

the way Mr. Bell died. He talked about how, in the<br />

absence of the U.S. Army, it fell to the men of the<br />

Nooksack Valley to protect their wives and children<br />

from what had happened to Mr. Bell. An example had<br />

to be made, he said.<br />

“This is the new frontier. Like the great frontiersmen<br />

before us, we must defend what’s ours. It’s up to<br />

us to see that civilized justice is done.”<br />

“Hear, hear!” shouted Mr. Harkness.<br />

The room suddenly got loud, with everybody<br />

nodding his head and agreeing with his neighbor<br />

that what Mr. Osterman said was dead to right. The<br />

Indians had to know who was in charge. A proposal<br />

was made by Mr. Osterman that the men present<br />

should form the Nooksack Vigilance Committee—<br />

just as other frontier towns had done to uphold law<br />

and order. Mr. Harkness declared that the first order<br />

of business of the Nooksack Vigilance Committee<br />

was to make sure that Louie Sam paid for what he<br />

did to Mr. Bell. A plan took shape to set out that very<br />

day north to Canada to make sure justice was served<br />

against the renegade Indian—for nobody present was<br />

in a mood for assuming the Canadians would do what<br />

was right, what was needed.<br />

For the first time, Father spoke up.<br />

“According to Mr. Breckenridge,” he said, “Sheriff<br />

Leckie and the Canadian justice of the peace have<br />

gone to Sumas to make the arrest. We should wait<br />

until the sheriff comes back. See what he has to say<br />

about the situation.”<br />

“Maybe that’s how things are done where you come<br />

from, Mr. Gillies,” replied Mr. Osterman, “but we<br />

need surer justice!”<br />

“And swifter!” It was Dave Harkness talking now.<br />

Pete was at his elbow, puffed up— trying to look like<br />

as big a man as his pa. “Why wait? That Indian needs<br />

his neck stretched.”<br />

“Hold on a minute,” said Mr. Stevens, Abigail’s<br />

father. “They got procedures across the border. We<br />

could find ourselves in an international incident if we<br />

act out of turn.”<br />

“It was one of us that was killed,” called out Mr.<br />

Harkness. “It should be us that settles it!”<br />

Everybody was talking and shouting at once now,<br />

smelling blood.<br />

“But what if he’s holed up with the Sumas?” said<br />

Mr. Hopkins. “There’s hundreds of them. You think<br />

they’re going to just let us waltz in and take one of<br />

50 51

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

their own away?”<br />

“Then we’ll show them we got the numbers to<br />

stand up to them!” shouted Mr. Harkness.<br />

“We should dress up like warriors!” Mr.<br />

Breckenridge called out. “Give those savages a taste of<br />

their own medicine!”<br />

There was mayhem now, everybody talking so loud<br />

as to wake up even poor Mr. Bell. Mr. Osterman got<br />

up on Mrs. Hauser’s table and held up his hands to<br />

quiet them down.<br />

“Spread the word to those who aren’t here. We<br />

meet at The Crossing at nightfall.”<br />

“Wait!” It was Father speaking. Suddenly, all eyes<br />

were on him. “I’d like to hear what Mr. Moultray has<br />

to say about this expedition.”<br />

Everyone turned to Bill Moultray, the richest man<br />

among them and the one who holds the most weight.<br />

His brow was furrowed, like he was giving serious<br />

consideration to what was being proposed.<br />

“Well, Bill?” said Mr. Osterman. “What do you say?”<br />

You could hear a pin drop as the men waited for<br />

his blessing.<br />

“I say,” he pronounced at last, “that this is the time<br />

for every man to stand up and do what’s right.”<br />

And so it was agreed. The Nooksack Vigilance<br />

Committee would set out that night in disguise and<br />

under the cover of darkness to find Louie Sam, and<br />

avenge the death of James Bell.<br />

Chapter Six<br />

After the speeches, we gathered in a clearing on<br />

the Hausers’ land where the Hausers had buried two<br />

of their babies that died. John and I watched from<br />

the trees as they put Mr. Bell’s casket in the ground<br />

and filled in the hole, marking the spot with a small<br />

wooden cross to match those on the babies’ graves.<br />

Heathen or not, Mr. Bell was buried as a Christian.<br />

Soon as that was done, the men found their horses<br />

and wagons and set off for home to ready themselves<br />

for the night’s adventure. There was discussion<br />

about what form their warrior costumes should take.<br />

Somebody suggested they should paint their faces<br />

to make themselves look frightening, the way the<br />

Nooksack Indians and their cousins the Sumas do at<br />

their potlatches.<br />

Father spotted John and me as he walked to fetch<br />

Mae. He was not pleased to see us.<br />

“Why aren’t you two in school?”<br />

“Miss Carmichael dismissed us,” I said. Then I<br />

couldn’t stop myself from asking, “Are you going with<br />

52 53

Copyright <strong>Annick</strong> <strong>Press</strong> 2012<br />

them tonight?”<br />

“Never you mind what I’m doing, George.”<br />

“But Mr. Osterman said every man is needed.”<br />

Father reddened. He was angry now.<br />

“You two were inside there?”<br />

It was John who answered with his usual cheek,<br />

“Yes, sir. It’s our duty to defend the Nooksack Valley.”<br />

Father took a measure of John, like he was about to<br />

get angrier still. But, instead, he cooled right down.<br />

“I appreciate that, John,” Father said. “The best<br />

thing you can do to help is to keep watch over your<br />

mam and the wee ones.”<br />

I don’t know what made me say it—maybe it was<br />

the way that Father was looking at John like he was<br />

just as much of a man as I was—but without thinking<br />

about it I announced, “I’m going with you!”<br />

Father looked at me and let out a laugh.<br />

“To raid an Indian village? Nae, laddie, you are<br />

staying put.” With that he climbed up on Mae and<br />

started her away at a trot, calling back to us, “You boys<br />

get yourselves home.”<br />

John started hoofing it down the track, following<br />

Father and Mae. I stayed put.<br />

“Well, c’mon,” he said, turning back. “What are you<br />

waiting for?”<br />

“Go on ahead,” I told him. “I’ve got some business<br />

to attend to.”<br />

“The only business you got is minding Father.”<br />

“Go on,” I said. “I’ll be there soon.”<br />

“Fine with me, if what you want is a whipping.”<br />

With a shrug, John walked on. In truth I had no<br />

business whatsoever to keep me there. My gaze fell<br />

upon Pete, who looked as irritated as I felt. I walked<br />

over to him.<br />

“What do you want?” he said.<br />

“Nothing!” I barked back, matching his tone. “Can’t<br />

a fella say hello?”<br />

“I’m not in a ‘hello-ing’ mood right now.”<br />

Pete started walking down the path. I fell in<br />

beside him.<br />

“Aren’t you waiting for your pa?” I asked him.<br />

“He went ahead.”<br />

“He left you behind?”<br />

“Yes, he left me behind. What about it?”<br />

“He left you behind with us kids?”<br />

Pete stopped, turned. “You want a fat lip, George?”<br />

He held his fist up, curled tight. He would have hit<br />

me, too. Pete’s the type to act first and think about it<br />

later. But I decided to take a higher road.<br />

“I’m going with them tonight,” I said.<br />

I could see that took the wind out of Pete’s sails.<br />

“Your pa said you could?”<br />

“Doesn’t matter what he says. I’m going. It’s<br />

our duty to defend the Nooksack Valley,” I added,<br />

borrowing the phrase that had served John so well<br />

with Father.<br />

54 55