2013 Winter EAP PATHWAYS Newsletter - draft.pub

2013 Winter EAP PATHWAYS Newsletter - draft.pub

2013 Winter EAP PATHWAYS Newsletter - draft.pub

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

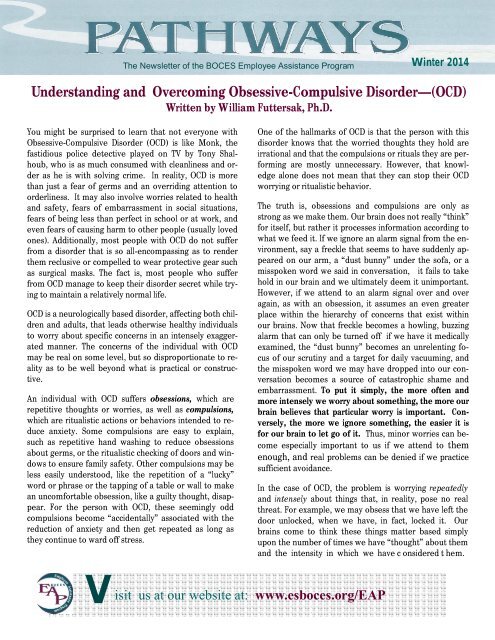

The <strong>Newsletter</strong> of the BOCES Employee Assistance Program <strong>Winter</strong> 2014<br />

Understanding and Overcoming Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder—(OCD)<br />

Written by William Futtersak, Ph.D.<br />

You might be surprised to learn that not everyone with<br />

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is like Monk, the<br />

fastidious police detective played on TV by Tony Shalhoub,<br />

who is as much consumed with cleanliness and order<br />

as he is with solving crime. In reality, OCD is more<br />

than just a fear of germs and an overriding attention to<br />

orderliness. It may also involve worries related to health<br />

and safety, fears of embarrassment in social situations,<br />

fears of being less than perfect in school or at work, and<br />

even fears of causing harm to other people (usually loved<br />

ones). Additionally, most people with OCD do not suffer<br />

from a disorder that is so all-encompassing as to render<br />

them reclusive or compelled to wear protective gear such<br />

as surgical masks. The fact is, most people who suffer<br />

from OCD manage to keep their disorder secret while trying<br />

to maintain a relatively normal life.<br />

OCD is a neurologically based disorder, affecting both children<br />

and adults, that leads otherwise healthy individuals<br />

to worry about specific concerns in an intensely exaggerated<br />

manner. The concerns of the individual with OCD<br />

may be real on some level, but so disproportionate to reality<br />

as to be well beyond what is practical or constructive.<br />

An individual with OCD suffers obsessions, which are<br />

repetitive thoughts or worries, as well as compulsions,<br />

which are ritualistic actions or behaviors intended to reduce<br />

anxiety. Some compulsions are easy to explain,<br />

such as repetitive hand washing to reduce obsessions<br />

about germs, or the ritualistic checking of doors and windows<br />

to ensure family safety. Other compulsions may be<br />

less easily understood, like the repetition of a “lucky”<br />

word or phrase or the tapping of a table or wall to make<br />

an uncomfortable obsession, like a guilty thought, disappear.<br />

For the person with OCD, these seemingly odd<br />

compulsions become “accidentally” associated with the<br />

reduction of anxiety and then get repeated as long as<br />

they continue to ward off stress.<br />

One of the hallmarks of OCD is that the person with this<br />

disorder knows that the worried thoughts they hold are<br />

irrational and that the compulsions or rituals they are performing<br />

are mostly unnecessary. However, that knowledge<br />

alone does not mean that they can stop their OCD<br />

worrying or ritualistic behavior.<br />

The truth is, obsessions and compulsions are only as<br />

strong as we make them. Our brain does not really “think”<br />

for itself, but rather it processes information according to<br />

what we feed it. If we ignore an alarm signal from the environment,<br />

say a freckle that seems to have suddenly appeared<br />

on our arm, a “dust bunny” under the sofa, or a<br />

misspoken word we said in conversation, it fails to take<br />

hold in our brain and we ultimately deem it unimportant.<br />

However, if we attend to an alarm signal over and over<br />

again, as with an obsession, it assumes an even greater<br />

place within the hierarchy of concerns that exist within<br />

our brains. Now that freckle becomes a howling, buzzing<br />

alarm that can only be turned off if we have it medically<br />

examined, the “dust bunny” becomes an unrelenting focus<br />

of our scrutiny and a target for daily vacuuming, and<br />

the misspoken word we may have dropped into our conversation<br />

becomes a source of catastrophic shame and<br />

embarrassment. To put it simply, the more often and<br />

more intensely we worry about something, the more our<br />

brain believes that particular worry is important. Conversely,<br />

the more we ignore something, the easier it is<br />

for our brain to let go of it. Thus, minor worries can become<br />

especially important to us if we attend to them<br />

enough, and real problems can be denied if we practice<br />

sufficient avoidance.<br />

In the case of OCD, the problem is worrying repeatedly<br />

and intensely about things that, in reality, pose no real<br />

threat. For example, we may obsess that we have left the<br />

door unlocked, when we have, in fact, locked it. Our<br />

brains come to think these things matter based simply<br />

upon the number of times we have “thought” about them<br />

and the intensity in which we have c onsidered t hem.<br />

V<br />

isit us at our website at: www.esboces.org/<strong>EAP</strong>

Intense, repetitive worrying only triggers additional cycles<br />

of OCD attention and worry. To reduce OCD, we must<br />

break these cycles of attention, worry, and ritualistic behavior.<br />

Traditionally, the treatment for OCD has involved talk<br />

therapy designed to help individuals gain insight into the<br />

subconscious motivations beneath their obsessive behaviors<br />

and/or behavioral therapy approaches designed<br />

to help the individual dispute the reasonableness of OCD<br />

behavior. Often, family members try to alleviate the<br />

worries of OCD sufferers through constant offerings of<br />

reassurance and even by forcibly trying to “block” loved<br />

ones from engaging in their compulsions.<br />

Jeffrey Schwartz, M.D., a neuroscientist, has demonstrated<br />

in his research why these types of interventions<br />

are generally not very helpful. By providing attention to<br />

the part of the brain that is obsessing, even in the context<br />

of trying to understand the worry, trying to dispute<br />

it, or trying to forcibly block it, only adds fuel to the obsessional<br />

thinking. Dr. Schwartz has developed the following<br />

four-step method to re-wire the brain and significantly<br />

reduce the impact of obsessional thinking. It has<br />

already shown great promise in the treatment of OCD.<br />

STEP ONE: RE-LABEL: In this first step, individuals with<br />

OCD learn to re-label their obsessive worries and compulsive<br />

urges. Rather than seeing them as legitimate<br />

alarm signals that must be attended to, OCD sufferers<br />

learn to re-label their worries as simple misfires of the<br />

brain. As a result, obsessive worry moves from the allimportant<br />

fear center of the brain to the part of the<br />

brain that handles “false alarms” from the environment<br />

of any type. Analogous to a telemarketer’s phone call at<br />

dinnertime, the OCD worry is reduced to the level of a<br />

nuisance, meant to be ignored rather than attended to.<br />

STEP TWO: RE-ATTRIBUTE: As Dr. Schwartz has described,<br />

obsessions are a creation of one’s own brain.<br />

In this second step, OCD sufferers use this knowledge to<br />

remind themselves of the true origin of their obsessive<br />

worries. Instead of attributing their worries to real<br />

world threats, OCD sufferers learn to diminish their fears<br />

by more accurately attributing them to their own previous<br />

patterns of obsessive thinking.<br />

STEP THREE: RE-VALUE: Based upon the insights gained<br />

during Steps 1 and 2, OCD sufferers can now more<br />

clearly see their worries as wasted energy expended on<br />

false threats. Knowing their obsessive worries have no<br />

real value, individuals with OCD can ignore, reject, or<br />

even make light of their own worries. In re-wIring the<br />

brain, Schwartz has found that it is much more effective<br />

for OCD sufferers to conclude for themselves that their<br />

obsessions have no real value rather than to rely upon<br />

the frequent reassurances of others.<br />

STEP FOUR: RE-FOCUS: Finally, having relabeled obsessive<br />

worrying as a misfiring of one’s own brain with no<br />

true value, the OCD sufferer can now refocus upon<br />

more constructive endeavors. Refocusing upon more<br />

positive concerns such as family relations, social interactions,<br />

leisure activities, etc. helps break the cycle of repetitive<br />

worry and reduces the importance of these worries<br />

in one’s own brain.<br />

According to Dr. Schwartz, repetitive practice of the 4-<br />

Steps--rather than repetition of obsessions and compulsions—ultimately<br />

leads to a rewiring of the brain and<br />

eventually frees an individual from the invisible bonds of<br />

OCD.<br />

If you or your family member(s) need assistance with<br />

this issue, or if you would like information regarding<br />

how to contact Dr. Futtersak, contact your <strong>EAP</strong> at (631)<br />

289-0480. WE ARE HERE FOR YOU!<br />

1741D North Ocean Avenue, Medford, NY 11763 (631) 289-0480<br />

35 Crooked Hill Road, Suite 103, Commack, NY 11725 (631) 858-9177<br />

188 W. Montauk Hwy, Ste. E1, Hampton Bays, NY 11946 (631) 728-2008<br />

Eastern Suffolk BOCES does not discriminate against any employee, student, applicant for employment, or candidate for enrollment on the basis of gender, race,<br />

color, religion or creed, age, weight, national origin, marital status, disability, sexual orientation, military or veteran status, domestic violence victim status, genetic<br />

predisposition or carrier status, or any other classification protected by Federal, State, or local law. Inquiries regarding the implementation of applicable laws<br />

should be directed to either of the Eastern Suffolk BOCES Civil Rights Compliance Officers: the Assistant Superintendent for Human Resources, 201 Sunrise<br />

Highway, Patchogue, NY 11772, 631-687-3029, ComplianceOfficers@esboces.org; or the Deputy Superintendent for Educational Services, 201 Sunrise Highway,<br />

Patchogue, NY 11772, 631-687-3056, ComplianceOfficers@esboces.org.