Sample Pages - Gale

Sample Pages - Gale

Sample Pages - Gale

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The House of Knopf: Historical Overview<br />

A Borzoi book on a library table or on the bookshelf<br />

is a mark of distinction always.<br />

—The American Mercury,<br />

Knopf Advertisement, 1928<br />

The publishing house of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. was<br />

shaped by the personalities of its founders, Alfred A. and<br />

Blanche Wolf Knopf. The brightly colored exterior and elegant<br />

typography of a Borzoi book produced by the firm paralleled<br />

Alfred Knopf’s penchant for sartorial display, and<br />

his aggressive salesmanship and love of good talk found its<br />

way into the company’s advertising copy imploring booksellers<br />

and the general reader to “Buy a Borzoi Book today!”<br />

Blanche Knopf’s affinity for foreign cultures, passionate<br />

love of good literature, and appreciation of the creative<br />

impulse brought a distinctive touch to the Knopf list. The<br />

Knopfs, the first husband-and-wife team among major<br />

American book publishers, were above all voracious, wideranging<br />

readers. (Their magnificent library is now at the<br />

Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.) The<br />

couple’s willingness to publish anything of significance<br />

that was of personal interest to them diversified the firm’s<br />

list beyond belles lettres and into American history, music,<br />

gastronomy, photography, and environmental conservation.<br />

Few publishers have been so intimately involved in<br />

every phase of the trade, including not only the cultivation<br />

of authors and acquisition of manuscripts but also book<br />

design, production, and marketing.<br />

The Knopfs’ involvement in the books they published<br />

insured a remarkable consistency—the publishing historian<br />

John Tebbel has called the Knopf list a “seamless<br />

web”—over a period of nearly seven decades. Clifton Fadiman,<br />

in his anthology Fifty Years: Borzoi Books<br />

1915–1965, cites other factors in the Knopf success formula,<br />

such as the establishment of a distinctive design<br />

and manufacturing style and the firm’s pioneering publication<br />

of important European and, later, Latin American<br />

and Japanese literature in translation. To this Fadiman<br />

adds a more elusive quality of the Knopfs: their “quiet<br />

elaboration of a classically restrained relationship between<br />

author and publisher.” This attitude of respect and sincere<br />

appreciation for their authors’ creative gifts was certainly<br />

not unique to the Knopfs, but they seemed to do a better job<br />

of communicating it than other publishers. In correspondence<br />

with the firm, the authors featured in this volume<br />

return again and again to the same theme—their loyalty<br />

to the publishers who saw to it that their works were handsomely<br />

presented, treated them fairly without exception,<br />

and regarded them as part of their circle of friends. As the<br />

Knopf advertising insistently proclaimed, “a publisher is<br />

always known by the company it keeps.” With reference to<br />

that standard, the house of Knopf must be regarded as one<br />

of the most important American publishers of the twentieth<br />

century.<br />

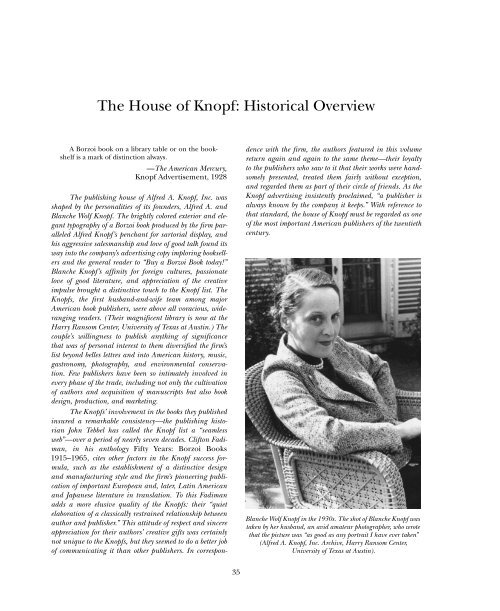

Blanche Wolf Knopf in the 1930s. The shot of Blanche Knopf was<br />

taken by her husband, an avid amateur photographer, who wrote<br />

that the picture was “as good as any portrait I have ever taken”<br />

(Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Archive, Harry Ransom Center,<br />

University of Texas at Austin).<br />

35

The House of Knopf: Historical Overview DLB 355<br />

This photograph of Alfred A. Knopf was taken in his office in the 1930s, probably for an article in Publishers’ Weekly<br />

(Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Archive, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin).<br />

The Knopfs’ Early Years<br />

Born 12 September 1892 to Samuel and Ida Japhe<br />

Knopf, Alfred A. Knopf grew up in a privileged household<br />

in New York, headed by his father, a wealthy advertising<br />

man of Russian Jewish extraction. His mother, who may<br />

have committed suicide, died when he was four years old.<br />

In 1908 Knopf entered Columbia College, where he was<br />

bored by most of his classes but inspired by a few professors,<br />

including Joel E. Spingarn, who prompted Alfred to begin<br />

collecting books. There were early signs of the boldness that<br />

later led to his success in business. Assigned to write an<br />

essay on a contemporary author, Knopf began a correspondence<br />

with John Galsworthy. Following his graduation in<br />

1912, he visited Europe and met with Galsworthy, who recommended<br />

the writers W. H. Hudson and Joseph Conrad—both<br />

played a role in Knopf’s earliest publishing<br />

ventures. Knopf also visited bookstores throughout<br />

England and Europe, noting the aesthetic appeal of certain<br />

books and choosing favorite publishers. By the end of<br />

the summer he said, “I came home . . . determined to be a<br />

publisher and not a lawyer as the family had intended.”<br />

Following a stint as an advertising salesman for<br />

The New York Times, Knopf was hired as an accountant<br />

by Doubleday, Page in 1912. He soon managed to<br />

involve himself in every phase of the publishing enterprise.<br />

Because of his familiarity with Conrad, he was<br />

one of the first to read the manuscript of Chance.<br />

Enthusiastic about the novel and displeased with Doubleday’s<br />

lackluster promotion, Knopf wrote to the most<br />

prominent authors of the day requesting testimonial<br />

blurbs, which were compiled into a promotional pamphlet,<br />

published in 1913, that contributed to the sale of<br />

50,000 copies of Chance. Knopf’s enthusiasm for Conrad<br />

led him to form a bond with the iconoclastic journalist<br />

H. L. Mencken, also a Conrad admirer.<br />

In March 1914 Knopf left Doubleday to join the<br />

English-born publisher Mitchell Kennerley as an assistant,<br />

in part because of his admiration for Kennerley’s<br />

commitment to good book design. Knopf honed his publicity<br />

skills and “traveled” for the firm—making important<br />

contacts as he sold Kennerley books to booksellers.<br />

His Kennerley days ended abruptly when the publisher<br />

discovered that his twenty-three-year-old employee was<br />

36

DLB 355<br />

The House of Knopf: Historical Overview<br />

about to found his own publishing company and<br />

planned to take a Kennerley author, the popular novelist<br />

Joseph Hergesheimer, along with him.<br />

Blanche Wolf was born in New York 30 July 1894<br />

to Julius and Bertha Wolf. Like her future husband,<br />

Blanche was from an upper-class background (the<br />

Wolfs considered themselves socially superior to the<br />

Knopfs). She was educated privately and graduated<br />

from the Gardner School. She met Alfred A. Knopf in<br />

1911 and, along with his father, encouraged him to<br />

start his own publishing firm. They were married 4<br />

April 1916, while Alfred was still drawing only $25<br />

dollars a week from the company.<br />

* * *<br />

In these excerpts from his memoirs Alfred Knopf<br />

recalls his life growing up in New York and his marriage to<br />

Blanche Wolf.<br />

“Onward and Upward”<br />

Alfred A. Knopf<br />

I was born in New York at what was then 234<br />

Central Park West, September 12th, 1892. My<br />

father, Samuel, was born thirty years earlier in<br />

Russian Poland. The only boy in a family of six<br />

children, he was brought to New York at an early<br />

age. My mother, Ida Japhe, of whom my father<br />

apparently found it difficult to speak, died, I think<br />

a suicide, when I was very young and I have no<br />

memory of her. But in 1949, after Geoffrey Hellman’s<br />

Profile of me appeared in The New Yorker, a<br />

lady, a stranger, wrote me that she had been in<br />

1887-8 in a class my mother taught at a public<br />

school. The letter continued: “She was a splendid<br />

teacher. Not only did she know her subject thoroughly,<br />

but she had that wonderful facility of<br />

being able to impart it to the immature mind. I<br />

loved her. When you were about one year old,<br />

your mother wanted me to see her baby. One of<br />

the things I remember you did was to open your<br />

father’s box of cigars, take one out and proceed to<br />

break it. Your mother said it was perfectly all<br />

right, the cigar cost only fifty cents (father always<br />

had a taste for fine cigars) and you would break a<br />

fifty cent toy just as quickly. You evidently had a<br />

taste for cigars at an early age.” . . .<br />

I have a few memories of my early childhood, but<br />

one stands out clearly--walking with a Negro manservant<br />

along the bluff overlooking a river and I think this<br />

must have been in Cincinnati about 1895 when my<br />

father was in business there.<br />

Alfred Knopf as a young man (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Archive,<br />

Harry Ransom Center, University<br />

of Texas at Austin)<br />

Around the turn of the century we moved to<br />

what for us was the City--a three story and basement<br />

house on the East Side of Convent Avenue<br />

just below 148th Street . . .<br />

We were a mixed-up family by [1901].<br />

There was my sister Sophia, Elizabeth, a stepsister,<br />

child of my stepmother by her first marriage<br />

and several years older than the rest of us, and<br />

my half brother Edwin, who was born in 1899.<br />

The reader can imagine how badly at times such<br />

an assortment got along with one another. But<br />

on the whole I spent my time with other boys<br />

though I can only remember the Blacks who<br />

lived across the street . . . , the Perines who lived<br />

next door to the south and Julian Marx whom we<br />

didn’t much like. But there must have been oth-<br />

37

The House of Knopf: Historical Overview DLB 355<br />

ers for we spent many an afternoon chasing and<br />

being chased by ‘gangs’ of what we called ‘micks.’<br />

I am not too clear about the exact order of<br />

my schooling. I think I went for a while to Public<br />

School #46 at 156th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue.<br />

Then a brief spell at Horace Mann where I<br />

developed kleptomania and stole—yes—books.<br />

When, before long, I was found out, Father managed<br />

somehow to remove me from the school<br />

without any publicity and then enrolled me at P.S.<br />

#186 on 145th Street, east of Broadway. There was<br />

a branch of the Public Library next door. I frequented<br />

it and another branch on St. Nicholas<br />

Avenue near 155th Street . . . In that way I discovered<br />

Conan Doyle, and Sherlock Holmes remains<br />

to this day the only wholly satisfying detective I<br />

have ever read about . . .<br />

Father must have been prospering in those<br />

days because we lived well. However, I don’t<br />

remember what his business was at the time and<br />

it may be that by present-day standards his<br />

income was very modest. Consider the house in<br />

which the six of us lived, with a cook, a chambermaid-waitress-laundress<br />

and a governess. The help<br />

was almost always Irish, but one governess was a<br />

Danish lady of distinguished presence who dined<br />

with the family. . . .<br />

We went to the country every summer.<br />

Except for one season on the Jersey coast, we were<br />

usually in Far Rockaway on the south shore of<br />

Long Island . . . Alfred Stieglitz summered not far<br />

away and toward sunset used to come tramping<br />

down the road with his wife (she was related by<br />

marriage to my stepmother) both carrying his<br />

camera, tripod and other equipment. . . .<br />

We observed only the Jewish Holy Days,<br />

though on the Day of Atonement, a solemn day of<br />

fasting for Jews who took the faith really seriously,<br />

we children were always taken to the Plaza for<br />

lunch which sort of made up for the boredom of<br />

the services. Most reformed Jews were no longer<br />

religious in a formal sense. I first went to Temple<br />

Israel of Harlem, Maurice Harris, Rabbi, and my<br />

only recollection is of hearing John D. Rockefeller<br />

for the first time. The good teacher impressed on<br />

us that though he was the world’s richest man, he<br />

had to live on a diet of crackers and milk. Later<br />

Father joined the much more fashionable Congregation<br />

of Temple Beth-El at 76th Street and Fifth<br />

Avenue and there, though we spent much time<br />

running three-legged races in the basement with<br />

the son of the Rabbi, Samuel Schulman, as the<br />

ringleader, I must have learned something for I<br />

was confirmed, had to make some kind of a talk in<br />

the Temple and was awarded a silver medal. Later,<br />

onward and upward as the New York Jewish bourgeoisie<br />

usually moved, we worshipped at Temple<br />

Emanu-El, first at 43rd and now at 66th Street on<br />

Fifth Avenue. One could go no higher. (Later<br />

Beth-El was torn down and in June 1932 when<br />

Father was buried from Emanu-El old Dr. Schulman<br />

delivered the Eulogy.) . . .<br />

* * *<br />

At Columbia University, Alfred Knopf enrolled in<br />

one of Spingarn’s final classes. Author of A History of<br />

Literary Criticism in the Renaissance (1899) and<br />

The New Criticism (1911), Spingarn taught at<br />

Columbia from 1899 to 1911 and went on to become<br />

one of the first white leaders of the National Association<br />

for the Advancement of Colored People.<br />

Knopf wrote a prize-competition essay on Galsworthy’s<br />

works that he sent to Galsworthy, sparking a lifelong<br />

correspondence and friendship. Galsworthy never<br />

published with Knopf but was helpful to the aspiring<br />

publisher early on in Knopf’s career.<br />

John Galsworthy to Alfred A. Knopf,<br />

15 February 1911<br />

Dear Mr. Knopf<br />

Thank you very warmly for your letter and<br />

the copy of your essay. It was most interesting to<br />

read and is surely quite a remarkable effort for<br />

your age. Of course there are differences of judgement<br />

between us, but I think you are right in placing<br />

‘The Man of Property’ and ‘Fraternity’ at the<br />

top of the novels. I don’t know whether I agree<br />

that ‘Justice’ is superior to ‘Strife’; it is in spirit, I<br />

think, but is not the equal of ‘Strife’ in its dramatic<br />

quality—<br />

I am glad you speak well of the short things,<br />

or rather, I am glad you like them.<br />

I don’t agree that your style is “rather<br />

wretched”; it is clear, terse, and manages to say<br />

what you want to say. If your essay does not<br />

receive its reward, it will be, I think, because you<br />

have rather overdone the description of plot and<br />

quotation in proportion to analysis of spirit,<br />

style, and mood; but I hope very sincerely it will<br />

get you the prize. Anyway, it has given me much<br />

pleasure.<br />

Yours very truly<br />

John Galsworthy<br />

38

DLB 355<br />

The House of Knopf: Historical Overview<br />

A 1912 letter from John Galsworthy to Alfred Knopf, following through on the author’s suggestion that Knopf should pursue the<br />

American publication of W. H. Hudson (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Archive, Harry Ransom Center,<br />

University of Texas at Austin)<br />

39

The House of Knopf: Historical Overview DLB 355<br />

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.<br />

With seed money from Samuel Knopf, the firm of<br />

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. began its existence in May 1915, a<br />

couple of months after Alfred and Blanche’s engagement,<br />

with the publication of Émile Augier’s Four Plays. Ten<br />

other titles appeared during Knopf’s first year. The firm’s<br />

headquarters were located in one room at 220 West 42nd<br />

Street in Manhattan. From the outset the Knopf list<br />

included a large proportion of foreign authors, especially<br />

French and Russian ones, in part because it was relatively<br />

easy to obtain their American rights and production costs<br />

were kept low by using English sheets instead of resetting<br />

text. Borzoi Books, as they were named because of Blanche’s<br />

short-lived attachment to the dog breed, featured decorated<br />

bindings, eye-catching dust jackets, and tasteful typography.<br />

In summer 1918 Alfred became president of the firm,<br />

a newly created title he held for thirty-nine years.<br />

* * *<br />

In these excerpts from his memoirs Knopf recalls the<br />

early years of his publishing house and his marriage to<br />

Blanche, including the birth of their only child, Pat, in<br />

1918.<br />

“Not Doing Too Well”<br />

Alfred A. Knopf<br />

. . . Blanche and I finally felt we could risk marriage,<br />

and on the sixteenth of April, 1916, we were<br />

married at the St. Regis, which still had a beautiful<br />

suite on the second floor which overlooked Fifth<br />

Avenue. The good hotels had not yet found it economically<br />

necessary to rent their best fronts to retail<br />

stores. Indeed, the St. Regis has left this room<br />

exactly as it was in 1915, and in 1965 the Chevaliers<br />

de Tastevin held one of their dinners in it. There was<br />

a large attendance at the ceremony and the elegant<br />

luncheon which followed was attended by friends of<br />

the family and relatives, with only a sprinkling of our<br />

own friends, because we were really only interested<br />

in ourselves and the world of books and music. The<br />

ceremony was performed by a city magistrate, Alexander<br />

H. Geismar, who had married a niece of my<br />

father. He had started out as a rabbi but soon lost his<br />

religious convictions and went into politics. We had<br />

a high regard and affection for him, and in any case<br />

did not want a religious ceremony.<br />

We believed that we should support ourselves<br />

and that we could manage on the seventy-five dollars<br />

a week the business could probably pay me.<br />

On this basis we believed we could afford to<br />

pay seventy-five dollars a month for rent and spent<br />

Alfred Knopf in 1915, the year of the firm’s founding<br />

(photograph by E. O. Hoppé; Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.<br />

Archive, Harry Ransom Center, University<br />

of Texas at Austin)<br />

some weeks before the wedding house-hunting in<br />

Westchester. We found one that suited us but not the<br />

family, and as a result Blanche’s parents insisted on<br />

buying and furnishing a very attractive small house<br />

for us in Greenacres, a newish development in<br />

Hartsdale. . . .<br />

We kept house with a maid-of-all-work to whom<br />

we paid very modest wages, and we entertained a lot.<br />

Authors came up from the city for lunch or dinner<br />

or weekends and often stayed overnight. Later, when<br />

America entered the war, the help problem became<br />

acute and we ended with an unmarried mother from<br />

the Bedford Reformatory whose child delighted<br />

Blanche and our friends by always calling me<br />

“Dada”. We got ourselves the first of two real Borzois—the<br />

most undoggy dogs I have ever<br />

known—and one day a fellow turned up at the office<br />

with a mongrel bull he wanted to sell for fifteen dollars.<br />

I bought him, and Pete remained our devoted<br />

pal until we moved to the city in the fall of 1918.<br />

Then we gave him to Pendleton and Hermine Dudley<br />

in Pleasantville where he became a town character.<br />

He usually hung around a traffic officer, was<br />

thrown more than once by a locomotive, but lived,<br />

40