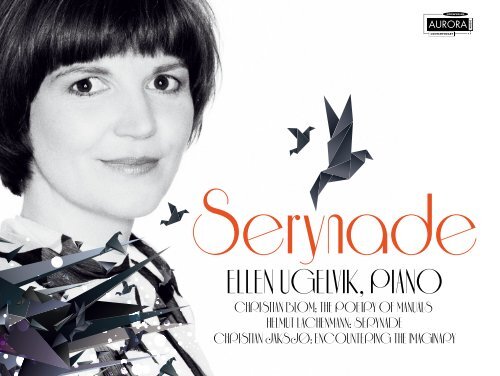

ELLEN UGELVIK, PIANO

ELLEN UGELVIK, PIANO

ELLEN UGELVIK, PIANO

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Serynade<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

CHRISTIAN BLOM: THE POETRY OF MANUALS<br />

HELMUT LACHENMANN: SERYNADE<br />

CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ: ENCOUNTERING THE IMAGINARY

1. CHRISTIAN BLOM<br />

The poetry of manuals<br />

— 13:01<br />

— MIC<br />

2. HELMUT LACHENMANN<br />

Serynade<br />

— 23:12<br />

—<br />

BREITKOPF & HÄRTEL<br />

3. CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ<br />

Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses]<br />

– for ring modulated electromechanically amplified piano and electronic sound<br />

— 24:00<br />

— MIC<br />

M<br />

Encou<br />

f<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

When does the p<br />

great virtuoso<br />

Etude flawlessly<br />

pianist only scra<br />

making a gratin<br />

knocks on the w<br />

who doesn't pla<br />

2

CHRISTIAN BLOM<br />

Manualenes poesi (2007–11) for piano<br />

HELMUT LACHENMANN<br />

Serynade (1998/2000) for piano<br />

CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ<br />

Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses] (2009/10)<br />

for ring modulated electromechanically<br />

amplified piano and electronic sound<br />

—<br />

BY BJÖRN GOTTSTEIN<br />

—<br />

When does the piano become a piano? Only when a<br />

great virtuoso performs Chopin's Revolutionary<br />

Etude flawlessly and magnificently on it? What if the<br />

pianist only scrapes his fingernails along the keys,<br />

making a grating sound? How about a pianist who<br />

knocks on the wood of the instrument? Or a pianist<br />

who doesn't play at all?<br />

The certainty with which the piano has been played<br />

and listened to up until the middle of the 20th century<br />

has been upset by the music of the avant-garde. A<br />

composer writing a piece for the piano today has to<br />

deal with the fact that striking a key is only one of<br />

many options. Yet the pianist in Helmut Lachenmann's<br />

piece Serynade is still expected to treat the piano in a<br />

3

conventional manner. The historical dialectics of the<br />

instrument itself, the inescapable conflict of being an<br />

expensive piece of furniture assuring the bourgeois<br />

self-conception on the one hand, and being a<br />

laboratory of sound experiment and aesthetic change<br />

on the other, may never be resolved. It is rather within<br />

this conflict that the prospects of contemporary piano<br />

music unfold. Many of the earlier pieces Lachenmann<br />

has written for the piano have exposed single aspects<br />

of the instrument, like the grating sound in Guero<br />

(1970) or the isolation of different parameters and filter<br />

effects in Ein Kinderspiel (1980).<br />

Serynade is actually the first large-scale piece<br />

Lachenmann has written for piano solo. The title refers<br />

to a genre of light music to be performed outdoors<br />

and/or in the evening, related to the ständchen and the<br />

divertimento. (The misspelling "y" in the title refers to<br />

the dedicatee of the piece, Yukiko Sugawara.) There is<br />

in fact a lightness and leisure to be found in this piece.<br />

The glissando from the bottom to the top of the<br />

keyboard is really just for show, a gesture hardly to be<br />

taken seriously as material; it expresses nothing but<br />

the bold manner in which something is brushed away.<br />

The question remains of what happens to the music<br />

that Lachenmann evokes. Almost all the figures and<br />

techniques Lachenmann uses have been explored and<br />

contextualized. He is thus not inventing anything from<br />

a technical point of view, instead the question he<br />

seems to be asking recalls Arnold Schoenberg's<br />

question when he was told that many young<br />

composers were using his dodecaphonic method:<br />

"Yes, but do they also make music?"<br />

One may listen to Lachenmann's Serynade as an<br />

essay on musical expression. Can a musical gesture<br />

that has been coded with meaning be used in an<br />

original, genuine way? The answer is of course yes,<br />

as 600 years of keyboard music have proved. Yet<br />

Lachenmann's focus seems to point further and<br />

further into the piano itself, as if he is directing his<br />

musical imagination into the nooks of the instrument,<br />

searching for a residue of resonance within the<br />

vibrating wood. One of the figures central to<br />

Lachenmann's piece is the sound shadow cast when<br />

a silently struck piano string vibrates sympathetically.<br />

This effect reveals the gap between the façade of<br />

sound, the outspokenness of the struck key, and its<br />

inner life.<br />

In Manualenes poesi Christian Blom uses the same<br />

effect to conceal the poetic core of the music behind<br />

a wall of staccato clusters. Of course, the clusters in<br />

the foreground are themselves musical and not just a<br />

disturbance, they are dry and hard and without<br />

humour. The chords that sound sympathetically are<br />

made possible by this façade of sounds in the first<br />

place. Still the essence of the music does not unfold in<br />

the forefront, it has been moved to the periphery of not<br />

only the instrument, but of the listening radius<br />

altogether. "Do you understand?" he asks the pianist<br />

when the second part, a Satie-like arrangement of<br />

chords, begins. "Understand" that the keys that are<br />

now struck correspond with the ghost sounds from<br />

the first part. When Jacques Derrida developed the<br />

idea of “hauntology” he was not thinking about music.<br />

Yet the idea of a haunting of ideas and sounds<br />

undercutting the musical present has been adapted<br />

by many com<br />

decade. The li<br />

also means that<br />

to put it solemn<br />

It is not alwa<br />

interesting let a<br />

Among the gho<br />

the haunting vo<br />

exposed to. It i<br />

driven mad by m<br />

the Imaginary<br />

regions of soun<br />

listener (for th<br />

preludes the sc<br />

describing the<br />

4

ynade as an<br />

usical gesture<br />

be used in an<br />

of course yes,<br />

e proved. Yet<br />

t further and<br />

s directing his<br />

the instrument,<br />

ce within the<br />

s central to<br />

ow cast when<br />

ympathetically.<br />

the façade of<br />

ck key, and its<br />

uses the same<br />

music behind<br />

the clusters in<br />

l and not just a<br />

and without<br />

athetically are<br />

ds in the first<br />

es not unfold in<br />

eriphery of not<br />

tening radius<br />

sks the pianist<br />

rrangement of<br />

keys that are<br />

t sounds from<br />

developed the<br />

g about music.<br />

s and sounds<br />

been adapted<br />

by many composers and artists within the last<br />

decade. The listening of elsewhere and elsewhen<br />

also means that we are shifting perspectives, that we,<br />

to put it solemnly, are pushing frontiers.<br />

It is not always the loudest who are the most<br />

interesting let alone the most intelligent to listen to.<br />

Among the ghosts of the past we most certainly find<br />

the haunting voices of the Sirens that Ulysses was<br />

exposed to. It is, of course, an aspiring claim to be<br />

driven mad by music. Christian Jaksjø's Encountering<br />

the Imaginary [Ulysses] is an attempt to access<br />

regions of sound that have been withdrawn from the<br />

listener (for the sake of his own safety). Jaksjø<br />

preludes the score with a text by Maurice Blanchot,<br />

describing the song of the Sirens as unfulfilling yet<br />

being "a sign of where the real sources and real<br />

happiness of song opened", and the text seems like an<br />

antedated description of Jaksjø's piece, in which the<br />

instrument is engaged in a self-modulating song<br />

through an elaborate electro-acoustic exchange<br />

between the played piano part and an electronic<br />

soundtrack. There is also a close connection between<br />

Jaksjø's Encountering the Imaginary and<br />

Lachenmann's Serynade, the material of the former<br />

having been derived from the latter, exposing those<br />

sounds that Lachenmann only hinted at. But more<br />

than being a frottage of Lachenmann's piece Jaksjø<br />

has tapered the project of listening deeply and<br />

beyond, turning the piano into a guidepost that leads<br />

well into the 21st century.<br />

5

CHRISTIAN BLOM<br />

Manualenes poesi (2007–11) for klaver<br />

HELMUT LACHENMANN<br />

Serynade (1998/2000) for klaver<br />

CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ<br />

Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses] (2009/10)<br />

for ringmodulert elektromekanisk forsterket klaver<br />

og elektronisk lyd<br />

Når blir klaveret til et klaver? Utelukkende når en<br />

stor virtuos framfører Chopins Revolusjonsetyde på<br />

det, feilfritt og imponerende? Hva hvis pianisten bare<br />

gnir fingerneglene sine langs tangentene med en<br />

skrapende lyd? Hva med pianisten som dunker på<br />

treet i instrumentkroppen? Hva med pianisten som<br />

ikke spiller overhodet?<br />

—<br />

AV BJÖRN GOTTSTEIN<br />

—<br />

Fram til midten av det 20. århundre er klaveret blitt spilt<br />

på og lyttet til med en sikkerhet som avantgarden<br />

deretter forstyrret. En komponist som vil skrive for<br />

klaver i dag, må forholde seg til at det å trykke ned<br />

tangenter bare er en av mange muligheter. Likevel<br />

forventes det at pianisten i Helmut Lachenmanns verk<br />

Serynade også kan behandle instrumentet innenfor<br />

konvensjonelle<br />

som er gitt a<br />

konflikten mello<br />

borgerlig selvfo<br />

laboratorium fo<br />

utvikling på den<br />

på innsiden av<br />

tids musikk for k<br />

stykkene Lache<br />

fram enkeltstå<br />

som den skra<br />

isolasjonen av u<br />

Ein Kinderspiel<br />

Serynade er fa<br />

Lachenmann sk<br />

lettere musikk fr<br />

slekt med form<br />

(Den feilstaven<br />

som verket er<br />

lette og frie finn<br />

fra de dype til<br />

show-off, en ge<br />

materiale; den<br />

forsøk på å børs<br />

med, er hva som<br />

framkaller. Næ<br />

Lachenmann be<br />

plassert i en sa<br />

teknisk sett ikke<br />

han tilsynelate<br />

Schönberg stilt<br />

komponister til<br />

«Ja, men lager<br />

6

10)<br />

aver<br />

averet blitt spilt<br />

avantgarden<br />

vil skrive for<br />

t å trykke ned<br />

gheter. Likevel<br />

enmanns verk<br />

ntet innenfor<br />

konvensjonelle rammer. Den historiske dialektikken<br />

som er gitt av klaveret selv, den uomgjengelige<br />

konflikten mellom å være et dyrt møbel som bekrefter<br />

borgerlig selvforståelse på den ene siden, og et<br />

laboratorium for klanglige eksperimenter og estetisk<br />

utvikling på den andre, er umulig å løse. Det er snarere<br />

på innsiden av denne konflikten at mulighetene i vår<br />

tids musikk for klaver utfolder seg. Mange av de tidlige<br />

stykkene Lachenmann har skrevet for klaver, viser<br />

fram enkeltstående egenskaper ved instrumentet,<br />

som den skrapende lyden i Guero (1970) eller<br />

isolasjonen av ulike parametre og filtreringseffekter i<br />

Ein Kinderspiel (1980).<br />

Serynade er faktisk det første verket i stor skala<br />

Lachenmann skrev for klaver solo. Tittelen henviser til<br />

lettere musikk framført utendørs og/eller om kvelden, i<br />

slekt med former som ständchen og divertimento.<br />

(Den feilstavende «y»-en i tittelen viser til utøveren<br />

som verket er tilegnet, Yukiko Sugawara.) Både det<br />

lette og frie finnes virkelig i dette stykket. Glissandoen<br />

fra de dype til de lyse tangentene nærmer seg en<br />

show-off, en gest det er vanskelig å ta alvorlig som<br />

materiale; den uttrykker ikke annet enn et dristig<br />

forsøk på å børste noe vekk. Spørsmålet vi sitter igjen<br />

med, er hva som hender med musikken Lachenmann<br />

framkaller. Nær sagt alle figurer og teknikker<br />

Lachenmann benytter seg av, er allerede utforsket og<br />

plassert i en sammenheng. Slikt sett oppfinner han<br />

teknisk sett ikke noe nytt. I stedet minner spørsmålet<br />

han tilsynelatende stiller, om spørsmålet Arnold<br />

Schönberg stilte da han ble fortalt at mange unge<br />

komponister tilegnet seg tolvtoneteknikkene hans:<br />

«Ja, men lager de også musikk?»<br />

Man kan lytte til Lachenmanns Serynade som et<br />

essay i å uttrykke seg musikalsk. Kan en musikalsk<br />

gest som er ladet med mening, fortsatt brukes på en<br />

måte som vil bli oppfattet som original og ekte?<br />

Svaret er selvsagt ja, og 600 år med musikk for<br />

tangentinstrumenter beviser det. Likevel peker<br />

Lachenmann tilsynelatende videre, stadig lengre inn i<br />

klaveret, som om han leder sin musikalske fantasi inn<br />

i instrumentets innerste hjørner, på jakt etter rester av<br />

resonans inne i det vibrerende treet. En sentral figur i<br />

Lachenmanns stykke er skyggen lyden kaster når en<br />

av strengene i klaveret vibrerer sympatisk eller<br />

passivt, kun satt i bevegelse av vibrasjonen i de andre<br />

strengene. Denne effekten avslører avstanden<br />

mellom lydens fasade, selve det uttalte ved tangenten<br />

som blir slått an, og lydens indre liv.<br />

I Manualenes poesi bruker Christian Blom samme<br />

effekt til å skjule en poetisk kjerne i musikken bak en<br />

vegg av staccato clustre. Selvfølgelig er clustrene i<br />

forgrunnen også musikalske og ikke bare der for å<br />

forstyrre, de er tørre, harde og blottet for humor.<br />

Akkordene som klinger passivt hadde ikke vært<br />

mulige uten denne fasaden av lyd i første omgang.<br />

Likevel utfolder ikke det essensielle i denne musikken<br />

seg i forgrunnen, det er flyttet til utkanten, ikke bare av<br />

instrumentet, men av lyttingens radius overhodet.<br />

«Forstår du?» spør han pianisten, når annen del, et<br />

Satie-aktig arrangement av akkorder, begynner.<br />

«Forstår» at tangentene nå trykkes ned i samsvar med<br />

de spektrale klangene fra første del. Da Jacques<br />

Derrida utviklet begrepet om hauntology (av «haunt»,<br />

å hjemsøke), tenkte han ikke på musikk. Likevel har<br />

tanken om å sette ideer og lyder på prøve, på en måte<br />

7

What was the n<br />

its fault lie? Wh<br />

Some have alw<br />

song–a natural<br />

kinds?), but on<br />

possible way to<br />

that extreme de<br />

the normal con<br />

enchantment w<br />

reproduce the h<br />

som undergraver et musikalsk nå, blitt adoptert av<br />

mange komponister og kunstnere de siste ti årene. Å<br />

lytte annensteds og i en annen tid innebærer også at<br />

perspektivet skifter, at vi, for å si det høytidelig, flytter<br />

grenser.<br />

Det kraftigste er ikke alltid det mest interessante eller<br />

intelligente å lytte til. Sirenenes stemmer som<br />

hjemsøkte Ulysses, er utvilsomt skygger fra fortiden.<br />

De styrker ideen om at musikk kan drive mennesket<br />

fra forstanden. Christian Jaksjøs Encountering the<br />

Imaginary [Ulysses] prøver å skape tilgang til<br />

klanglige områder som er blitt unndratt lytteren (av<br />

sikkerhetshensyn). Som innledning til partituret har<br />

Jaksjø en tekst av Maurice Blanchot der sirenenes<br />

sang blir beskrevet som utilfredsstillende og samtidig<br />

«et tegn på hvor sangens virkelige kilder og gleder<br />

åpnet seg», og teksten virker som om den foregriper<br />

en beskrivelse av Jaksjøs stykke, der instrumentet<br />

engasjeres i en selvmodulerende sang gjennom en<br />

elektroakustisk utveksling mellom klaverstemmen og<br />

det elektroniske lydsporet. Det er også en nær<br />

sammenheng mellom Jaksjøs Encountering the<br />

Imaginary og Lachenmanns Serynade, i og med at<br />

materialet i det førstnevnte er utvunnet fra det<br />

sistnevnte og stiller ut de klangene som Lachenmann<br />

bare antydet eksistensen av. Men mer enn å være en<br />

overtegning av Lachenmanns verk, har Jaksjø<br />

fortsatt å gradbøye den dype lyttingen videre, og har<br />

gjort klaveret til en utkikkspost med utsikt langt inn i<br />

det 21. århundre.<br />

Enc<br />

The Sirens: it s<br />

unfulfilling way,<br />

real sources an<br />

by means of th<br />

song still to com<br />

space where s<br />

deceive him, in<br />

But what happ<br />

What was this<br />

left but to disap<br />

source and o<br />

completely than<br />

where, ears blo<br />

Sirens, as proof<br />

disappear.<br />

8

lder og gleder<br />

den foregriper<br />

r instrumentet<br />

g gjennom en<br />

erstemmen og<br />

også en nær<br />

ountering the<br />

e, i og med at<br />

unnet fra det<br />

Lachenmann<br />

enn å være en<br />

, har Jaksjø<br />

videre, og har<br />

tsikt langt inn i<br />

Encountering the Imaginary<br />

The Sirens: it seems they did indeed sing, but in an<br />

unfulfilling way, one that only gave a sign of where the<br />

real sources and real happiness of song opened. Still,<br />

by means of their imperfect songs that were only a<br />

song still to come, they did lead the sailor toward that<br />

space where singing might truly begin. They did not<br />

deceive him, in fact: they actually led him to his goal.<br />

But what happened once the place was reached?<br />

What was this place? One where there was nothing<br />

left but to disappear, because music, in this region of<br />

source and origin, had itself disappeared more<br />

completely than in any other place in the world: sea<br />

where, ears blocked, the living sank, and where the<br />

Sirens, as proof of their good will, had also, one day, to<br />

disappear.<br />

What was the nature of the Sirens’ song? Where did<br />

its fault lie? Why did this fault make it so powerful?<br />

Some have always answered: It was an inhuman<br />

song–a natural noise no doubt (are there any other<br />

kinds?), but on the fringes of nature, foreign in every<br />

possible way to man, very low, and awakening in him<br />

that extreme delight in falling that he cannot satisfy in<br />

the normal conditions of life. But, say others, the<br />

enchantment was stranger than that: it did nothing but<br />

reproduce the habitual song of men, and because the<br />

Sirens, who were only animals, quite beautiful<br />

because of the reflection of feminine beauty, could<br />

sing as men sing, they made the song so strange that<br />

they gave birth in anyone who heard it to a suspicion<br />

of the inhumanity of every human song. Is it through<br />

despair, then, that men passionate for their own song<br />

came to perish? Through a despair very close to<br />

rapture. There was something wonderful in this real<br />

song, this common, secret song, simple and everyday,<br />

that they had to recognize right away, sung in an<br />

unreal way by foreign, even imaginary powers, song<br />

of the abyss that, once heard, would open an abyss in<br />

each word and would beckon those who heard it to<br />

vanish into it.<br />

This song, we must remember, was aimed at sailors,<br />

men who take risks and feel bold impulses, and it was<br />

also a means of navigation: it was a distance, and it<br />

revealed the possibility of traveling this distance, of<br />

making the song into the movement toward the song,<br />

and of making this movement the expression of the<br />

greatest desire. Strange navigation, but toward what<br />

end? It has always been possible to think that those<br />

who approached it did nothing but come near to it, and<br />

died because of impatience, because they<br />

prematurely asserted: here it is; here, here I will cast<br />

9

anchor. According to others, it was on the contrary too<br />

late: the goal had already been passed; the<br />

enchantment, by an enigmatic promise, exposed men<br />

to being unfaithful to themselves, to their human song<br />

and even to the essence of the song, by awakening<br />

the hope and desire for a wonderful beyond, and this<br />

beyond represented only a desert, as if the<br />

motherland of music were the only place completely<br />

deprived of music, a place of aridity and dryness<br />

where silence, like noise, burned, in one who once<br />

had the disposition for it, all passageways to song.<br />

Was there, then, an evil principle in this invitation to<br />

the depths? Were the Sirens, as tradition has sought<br />

to persuade us, only the false voices that must not be<br />

listened to, the trickery of seduction that only disloyal<br />

and deceitful beings could resist?<br />

There has always been a rather ignoble effort among<br />

men to discredit the Sirens by flatly accusing them of<br />

lying: liars when they sang, deceivers when they<br />

sighed, fictive when they were touched; in every<br />

respect nonexistent, with a childish nonexistence that<br />

the good sense of Ulysses was enough to exterminate.<br />

treachery which led him to enjoy the entertainment of<br />

the Sirens, without risks and without accepting the<br />

consequences; his was a cowardly, moderate, and<br />

calm enjoyment, as befits a Greek of the decadent era<br />

who will never deserve to be the hero of the Iliad. His<br />

is a fortunate and secure cowardliness, based on<br />

privilege, which places him outside of the common<br />

condition–others having no right to the happiness of<br />

the elite, but only a right to the pleasure of watching<br />

their leader writhe ridiculously, with grimaces of<br />

ecstasy in the void, a right also to the satisfaction of<br />

mastering their master (that is no doubt the lesson<br />

they understood, the true song of the Sirens for them).<br />

Ulysses’ attitude, that surprising deafness of one who<br />

is deaf because he is listening, is enough to<br />

communicate to the Sirens a despair reserved till now<br />

for humans and to turn them, through this despair, into<br />

actual beautiful girls, real this one time only and<br />

worthy of their promise, thus capable of disappearing<br />

into the truth and profundity of their song.<br />

«Maurice Blanchot: The Book to Come»<br />

(Translated by Charlotte Mandell. Courtesy of Stanford University Press)<br />

It is true, Ulysses conquered them, but in what way?<br />

Ulysses, with his stubbornness and prudence, his<br />

10

tertainment of<br />

accepting the<br />

moderate, and<br />

e decadent era<br />

of the Iliad. His<br />

ess, based on<br />

f the common<br />

e happiness of<br />

re of watching<br />

grimaces of<br />

satisfaction of<br />

ubt the lesson<br />

irens for them).<br />

ss of one who<br />

is enough to<br />

served till now<br />

is despair, into<br />

time only and<br />

f disappearing<br />

g.<br />

»<br />

University Press)<br />

11

Christian Blom (1974) is an artist living on<br />

Nesoddtangen. He works with kinetic sculpture,<br />

mechanical devices and composition. Blom has a formal<br />

background as a guitarist and composer, counting a<br />

cand. philol in composition from the University of Bergen<br />

as a current academic highlight. Blom is constantly<br />

researching the parallells and differences in different<br />

media and their techniques. In particular on search for<br />

unexpected connections and perspectives.<br />

www.christianblom.com<br />

Christian Jaksjø’s musical background includes<br />

studies of improvisation, composition, and<br />

electro-acoustic music, an extensive performing<br />

career on trombone, euphonium, and related<br />

instruments, interdiciplinary experimental studies of<br />

dynamic form with architects, designers and<br />

engineers, along with a concurrent, groundbreaking<br />

creative practice as a composer: utilizing, for instance,<br />

processual musical transformation by means of<br />

discretely varying virtual n-tone equal-tempered<br />

divisions of the octave (Orthodrom/Loxodrom<br />

[Grosszirkelnavigation], 1997–2000); architecturized<br />

music composed algorithmically by means of complex<br />

dynamical systems operating directly on<br />

architectonical spatial structures by Jan Duiker<br />

(Ungrounded [Zonnestraal], 2002); stochastic<br />

algorithmic composition and sound synthesis directly<br />

operating on mystical texts by David Libeskind (The<br />

Four Texts, 2003) or also on the virtual instrumental<br />

resonance occurring in Helmut Lachenmann’s<br />

Serynade, and in the latter case combined with<br />

complex instrumental extension by means of ring<br />

Christian Blom (1974) er bosatt på Nesoddtangen.<br />

Han arbeider med kinetiske skulpturer, mekaniske<br />

innretninger og komposisjon. Blom har formell<br />

bakgrunn som gitarist og komponist med cand.<br />

philol i komposisjon fra Universitetet i Bergen som<br />

foreløpig akademisk høydepunkt. I sine prosjekter<br />

utforsker Blom forbindelser mellom ulike medier og<br />

deres teknikker. Med særlig blikk på uventede<br />

forbindelser og perspektiver.<br />

www.christianblom.com<br />

Christian Jaksjøs musikalske bakgrunn inkluderer<br />

studier i improvisasjon, komposisjon og<br />

elektroakustisk musikk, en omfattende karriere som<br />

utøver på trombone, euphonium og beslektede<br />

instrumenter, interdisiplinære eksperimentelle studier<br />

av dynamisk form med arkitekter, designere og<br />

ingeniører, ved siden av parallelt, banebrytende<br />

kreativt virke som komponist, uttrykt f.eks. gjennom:<br />

prosessuell musikalsk transformasjon ved hjelp av<br />

diskret varierende virtuelle n-toners tempereringer<br />

(Orthodrom/Loxodrom [Großzirkelnavigation],<br />

1997–2000); arkitektifisert musikk komponert<br />

algoritmisk ved hjelp av komplekse dynamiske<br />

systemer som opererer direkte på arkitektoniske<br />

romlige strukturer av Jan Duiker (Ungrounded<br />

[Zonnestraal], 2002); stokastisk algoritmisk<br />

komposisjon og lydsyntese som opererer direkte på<br />

mystiske tekster av David Libeskind (The Four Texts,<br />

2003), eller også på den virtuelle<br />

instrumentalresonansen slik den forekommer i Helmut<br />

Lachenmanns Serynade, og i dette tilfelle kombinert<br />

med en kompleks instrumental utvidelse ved hjelp av<br />

modulated elect<br />

feedback (Enco<br />

2009–2010). Pivo<br />

and as an impro<br />

forces as well a<br />

Christian Jaksjø<br />

was born in 197<br />

since 2003, play<br />

www.christianja<br />

Helmut Lachenm<br />

influential Europ<br />

early 21st centu<br />

Venice and Colo<br />

Beginning in the<br />

new and innova<br />

as temA (1968),<br />

(1969), for orche<br />

instruments and<br />

new sounds and<br />

instruments we<br />

questions past m<br />

postserialist com<br />

writings.<br />

Other works inc<br />

(1972), Accanto<br />

Estarrung) (1984<br />

(1984/85), Allegr<br />

for piano, and th<br />

A well-known te<br />

mentor to many<br />

12

soddtangen.<br />

, mekaniske<br />

r formell<br />

ed cand.<br />

Bergen som<br />

e prosjekter<br />

ike medier og<br />

ventede<br />

modulated electromechanical and electromagnetical<br />

feedback (Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses],<br />

2009–2010). Pivotal to his work, both as a composer<br />

and as an improviser, is rendering audible: underlying<br />

forces as well as otherwise imperceptible patterns.<br />

Christian Jaksjø lives and works in Oslo (where he<br />

was born in 1973) and in Frankfurt am Main (where he,<br />

since 2003, plays trombone in the hr-Bigband).<br />

www.christianjaksjø.no<br />

ringmodulert elektromekanisk og elektromagnetisk<br />

tilbakekobling (Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses],<br />

2009-10). Sentralt i hans virke, både som<br />

improviserende musiker og som komponist, er å gjøre<br />

hørbart: såvel bakenforliggende krefter som ellers<br />

uhørlige mønstre. Christian Jaksjø bor og arbeider i<br />

Oslo (hvor han ble født i 1973) og i Frankfurt am Main<br />

(hvor han, siden 2003, spiller trombone i hr-Bigband).<br />

www.christianjaksjø.no<br />

inkluderer<br />

karriere som<br />

lektede<br />

entelle studier<br />

nere og<br />

rytende<br />

ks. gjennom:<br />

ed hjelp av<br />

pereringer<br />

ation],<br />

nert<br />

amiske<br />

ektoniske<br />

unded<br />

isk<br />

er direkte på<br />

e Four Texts,<br />

mmer i Helmut<br />

lle kombinert<br />

e ved hjelp av<br />

Helmut Lachenmann (1935) is one of the most<br />

influential European composers of the late 20th and<br />

early 21st centuries. He studied with Luigi Nono in<br />

Venice and Cologne.<br />

Beginning in the late 1960s, Lachenmann explored a<br />

new and innovative musical language. In works such<br />

as temA (1968), for flute, voice and cello, and Air<br />

(1969), for orchestra and percussion soloist, he used<br />

instruments and voices unconventionally, producing<br />

new sounds and sound combinations in which all<br />

instruments were given equal weight. Lachenmann<br />

questions past musical assumptions in his many<br />

postserialist compositions and in his varied musical<br />

writings.<br />

Other works include the string quartet Gran Torso<br />

(1972), Accanto (1975/76), Mouvement (vor der<br />

Estarrung) (1984) for chamber orchestra, Ausklang<br />

(1984/85), Allegro Sostenuto (1986/88), Serynade (2000)<br />

for piano, and the opera The Little Match Girl (2001).<br />

A well-known teacher, Lachenmann has been a<br />

mentor to many important younger composers.<br />

Helmut Lachenmann (1935) er en av Europas mest<br />

innflytelsesrike komponister i det sene 20. og tidlige<br />

21. århundre. Han studerte med Luigi Nono i Venezia<br />

og i Köln.<br />

Mot slutten av 1960-årene begynte Lachenmann å<br />

utforske et helt nytt musikalsk språk. I verk som temA<br />

(1968), for fløyte, stemme og cello, og Air (1969), for<br />

orkester og solo slagverk, brukte han både<br />

instrumenter og stemmer på en ukonvensjonell måte,<br />

hvilket resulterte i nye klanger og klangkombinasjoner<br />

der samtlige instrumenter hadde likeverdige stemmer.<br />

Lachenmann setter spørsmålstegn ved tidligere<br />

musikalske antagelser i sine mange postserialistiske<br />

komposisjoner og artikler.<br />

På hans verkliste er bl.a. strykekvartetten Gran Torso<br />

(1972), Accanto (1975/76), Mouvement (vor der<br />

Estarrung) (1984) for kammerorkester, Ausklang<br />

(1984/85), Allegro Sostenuto (1986/88), Serynade (2000)<br />

for piano, og operaen Piken med svovelstikkene<br />

(2001). Lachenmann er også en høyt skattet lærer og<br />

mentor for unge komponister.<br />

13

Ellen Ugelvik c<br />

performing new<br />

composers. Sh<br />

the Grieg Acad<br />

Conservatorium<br />

Schleiermache<br />

Theater, Leipzig<br />

Ugelvik works a<br />

Europe, USA an<br />

festivals such a<br />

Internationalen<br />

Darmstadt, Ultra<br />

Huddersfield Co<br />

Muziekweek, M<br />

Nachts, Ultima C<br />

Borealis, ILIOS,<br />

Monday Evenin<br />

composers inclu<br />

Fujikura, Magne<br />

Jaksjø, Michael<br />

Birkelund, Claus<br />

Steen-Andersen<br />

Gadenstätter, H<br />

Ingvar Lidholm,<br />

Gjertsen.<br />

Her commitmen<br />

recognised. Sh<br />

performing arti<br />

in Norway. Her<br />

rewarded with<br />

member of the<br />

and Polygon.<br />

14

Ellen Ugelvik concentrates on discovering and<br />

performing new works by contemporary<br />

composers. She has studied with Einar Røttingen at<br />

the Grieg Academy in Bergen, Håkon Austbø at the<br />

Conservatorium van Amsterdam and Steffen<br />

Schleiermacher at the Hochschule für Musik und<br />

Theater, Leipzig.<br />

Ugelvik works as a soloist and chamber musician in<br />

Europe, USA and Asia. She has been invited to<br />

festivals such as Tasten – Berliner Klaviertage,<br />

Internationalen Ferienkurse für Neue Musik<br />

Darmstadt, Ultraschall, Gaudeamus, Rainy Days,<br />

Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, De Suite<br />

Muziekweek, Musik der Jahrhunderte; Südseite<br />

Nachts, Ultima Contemporary Music Festival,<br />

Borealis, ILIOS, Risør Festival of Chamber Music, and<br />

Monday Evening Concerts. She collaborates with<br />

composers including Helmut Lachenmann, Dai<br />

Fujikura, Magne Hegdal, Christian Blom, Christian<br />

Jaksjø, Michael Finnissy, Unsuk Chin, Therese<br />

Birkelund, Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf, Simon<br />

Steen-Andersen, Sven Lyder Kahrs, Clemens<br />

Gadenstätter, Helmut Oehring, Trond Reinholdtsen,<br />

Ingvar Lidholm, Nicholas A. Huber and Ruben S.<br />

Gjertsen.<br />

Her commitment to contemporary music is widely<br />

recognised. She recently received a state grant for<br />

performing artists, one of the most coveted awards<br />

in Norway. Her first solo album, Makrokosmos was<br />

rewarded with the Norwegian Grammy. She is a<br />

member of the ensembles asamisimasa, Jagerflygel<br />

and Polygon.<br />

Ellen Ugelvik er utdannet ved Konservatoriet i<br />

Amsterdam, Musikkhøyskolen i Leipzig og<br />

Griegakademiet i Bergen med Håkon Austbø,<br />

Steffen Schleiermacher og Einar Røttingen som<br />

veiledere.<br />

Ugelvik har fordypet seg i fremføring av<br />

samtidsmusikk og konserterer som solist og<br />

kammermusiker over hele verden. Hun har deltatt<br />

på samtidsmusikkfestivaler som Tasten – Berliner<br />

Klaviertage, Internationalen Ferienkurse für Neue<br />

Musik Darmstadt, Ultraschall, Gaudeamus, Rainy<br />

Days, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival,<br />

De Suite Muziekweek, Musik der Jahrhunderte;<br />

Südseite Nachts, Ultima, Borealis, ILIOS, Risør<br />

Kammermusikkfest og Monday Evening Concerts.<br />

Ellen Ugelvik har bestilt og uroppført en rekke<br />

verker og samarbeider med komponister som<br />

Helmut Lachenmann, Dai Fujikura, Magne Hegdal,<br />

Christian Blom, Christian Jaksjø, Michael Finnissy,<br />

Unsuk Chin, Therese Birkelund, Claus-Steffen<br />

Mahnkopf, Simon Steen-Andersen, Sven Lyder<br />

Kahrs, Clemens Gadenstätter, Helmut Oehring,<br />

Ingvar Lidholm, Nicholas A. Huber og Ruben S.<br />

Gjertsen.<br />

Hun har vært solist med de største orkestrene og<br />

ensemblene i Norge med bl.a. Helmut Lachenmanns<br />

klaverkonsert Ausklang, hvor hennes fremføring ble<br />

nominert til Kritikerprisen. Hennes første<br />

soloutgivelse Makrokosmos ble premiert med<br />

Spellemannprisen. Hun er medlem av ensemblene<br />

asamisimasa, Jagerflygel og Polygon.<br />

15

Norwegian Spellemann Prize 2008<br />

… the way the Ugelvik has so completely absorbed<br />

the required idiom make concentrated listening to<br />

Makrokosmos on the sensitively-recorded SACD a<br />

spell-binding experience. Ugelvik's [recording] must<br />

now be considered a worthy front-runner.<br />

[MusicWeb / Mark Sealy]<br />

– Ugelvik spiller fantastisk flott, jeg tror ikke stykkene<br />

kan spilles bedre. Dette er en plate jeg kommer til<br />

å høre igjen og igjen.<br />

[6/6 Erik Steinskog, Bergens Tidende]<br />

17

Serynade<br />

Recorded 8-10 N<br />

Producer: Tony<br />

Engineer: Geoff<br />

Editor: Stephen<br />

Steinway Grand<br />

Encountering th<br />

Recorded 30-31<br />

Producer, engin<br />

Technical super<br />

Bösendorfer 22<br />

Liner notes: Bjö<br />

Translation: Hild<br />

Cover design: M<br />

Photo: Observa<br />

Executive produ<br />

The poetry of m<br />

Norsk kulturråd<br />

©&π 2012 Norwegian<br />

All trademarks and log<br />

and of the owner of th<br />

copying, hiring, lending<br />

of this record prohibite<br />

Released with s<br />

18

Serynade<br />

Recorded 8-10 November 2009 in Sofienberg church, Oslo<br />

Producer: Tony Harrison<br />

Engineer: Geoff Miles<br />

Editor: Stephen Frost<br />

Steinway Grand Model D, technician Thron Irby<br />

Encountering the Imaginary and The poetry of manuals<br />

Recorded 30-31 May and 1 June 2011 in Vestfossen church<br />

Producer, engineer and editor: Sean Lewis<br />

Technical supervision electro-acoustics: Christian Jaksjø<br />

Bösendorfer 225, technician Tore Poulsen/Aspheim<br />

Liner notes: Björn Gottstein<br />

Translation: Hild Borchgrevink<br />

Cover design: Martin Kvamme<br />

Photo: Observatoriet<br />

Executive producer: Erik Gard Amundsen<br />

Released with support from: Norsk kulturråd and Norsk komponistforening<br />

The poetry of manuals and Encountering the Imaginary are commissioned by Ellen Ugelvik with support from<br />

Norsk kulturråd<br />

©&π 2012 Norwegian Society of Composers<br />

All trademarks and logos are protected. All rights of the producer<br />

and of the owner of the work reproduced reserved. Unauthorized<br />

copying, hiring, lending, public performance and broadcasting<br />

of this record prohibited. NOLFA1261010-030 · ACD5061 Stereo<br />

19

Serynade<br />

1. CHRISTIAN BLOM<br />

The poetry of manuals<br />

— 13:01<br />

—<br />

2. HELMUT LACHENMANN<br />

Serynade<br />

— 23:12<br />

—<br />

3. CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ<br />

Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses]<br />

– for ring modulated electromechanically amplified piano and electronic sound<br />

— 24:00<br />

—<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

Serynade<br />

7044581350614<br />

π&© 2012 NORWEGIAN SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS<br />

NOLFA1261010-030 · ACD 5061 · STEREO · TT 60:16<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

ACD 5061<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

ACD 5061