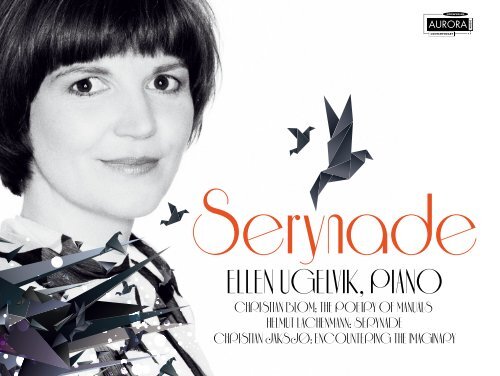

ELLEN UGELVIK, PIANO

ELLEN UGELVIK, PIANO

ELLEN UGELVIK, PIANO

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Serynade<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

CHRISTIAN BLOM: THE POETRY OF MANUALS<br />

HELMUT LACHENMANN: SERYNADE<br />

CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ: ENCOUNTERING THE IMAGINARY

1. CHRISTIAN BLOM<br />

The poetry of manuals<br />

— 13:01<br />

— MIC<br />

2. HELMUT LACHENMANN<br />

Serynade<br />

— 23:12<br />

—<br />

BREITKOPF & HÄRTEL<br />

3. CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ<br />

Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses]<br />

– for ring modulated electromechanically amplified piano and electronic sound<br />

— 24:00<br />

— MIC<br />

M<br />

Encou<br />

f<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

When does the p<br />

great virtuoso<br />

Etude flawlessly<br />

pianist only scra<br />

making a gratin<br />

knocks on the w<br />

who doesn't pla<br />

2

CHRISTIAN BLOM<br />

Manualenes poesi (2007–11) for piano<br />

HELMUT LACHENMANN<br />

Serynade (1998/2000) for piano<br />

CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ<br />

Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses] (2009/10)<br />

for ring modulated electromechanically<br />

amplified piano and electronic sound<br />

—<br />

BY BJÖRN GOTTSTEIN<br />

—<br />

When does the piano become a piano? Only when a<br />

great virtuoso performs Chopin's Revolutionary<br />

Etude flawlessly and magnificently on it? What if the<br />

pianist only scrapes his fingernails along the keys,<br />

making a grating sound? How about a pianist who<br />

knocks on the wood of the instrument? Or a pianist<br />

who doesn't play at all?<br />

The certainty with which the piano has been played<br />

and listened to up until the middle of the 20th century<br />

has been upset by the music of the avant-garde. A<br />

composer writing a piece for the piano today has to<br />

deal with the fact that striking a key is only one of<br />

many options. Yet the pianist in Helmut Lachenmann's<br />

piece Serynade is still expected to treat the piano in a<br />

3

conventional manner. The historical dialectics of the<br />

instrument itself, the inescapable conflict of being an<br />

expensive piece of furniture assuring the bourgeois<br />

self-conception on the one hand, and being a<br />

laboratory of sound experiment and aesthetic change<br />

on the other, may never be resolved. It is rather within<br />

this conflict that the prospects of contemporary piano<br />

music unfold. Many of the earlier pieces Lachenmann<br />

has written for the piano have exposed single aspects<br />

of the instrument, like the grating sound in Guero<br />

(1970) or the isolation of different parameters and filter<br />

effects in Ein Kinderspiel (1980).<br />

Serynade is actually the first large-scale piece<br />

Lachenmann has written for piano solo. The title refers<br />

to a genre of light music to be performed outdoors<br />

and/or in the evening, related to the ständchen and the<br />

divertimento. (The misspelling "y" in the title refers to<br />

the dedicatee of the piece, Yukiko Sugawara.) There is<br />

in fact a lightness and leisure to be found in this piece.<br />

The glissando from the bottom to the top of the<br />

keyboard is really just for show, a gesture hardly to be<br />

taken seriously as material; it expresses nothing but<br />

the bold manner in which something is brushed away.<br />

The question remains of what happens to the music<br />

that Lachenmann evokes. Almost all the figures and<br />

techniques Lachenmann uses have been explored and<br />

contextualized. He is thus not inventing anything from<br />

a technical point of view, instead the question he<br />

seems to be asking recalls Arnold Schoenberg's<br />

question when he was told that many young<br />

composers were using his dodecaphonic method:<br />

"Yes, but do they also make music?"<br />

One may listen to Lachenmann's Serynade as an<br />

essay on musical expression. Can a musical gesture<br />

that has been coded with meaning be used in an<br />

original, genuine way? The answer is of course yes,<br />

as 600 years of keyboard music have proved. Yet<br />

Lachenmann's focus seems to point further and<br />

further into the piano itself, as if he is directing his<br />

musical imagination into the nooks of the instrument,<br />

searching for a residue of resonance within the<br />

vibrating wood. One of the figures central to<br />

Lachenmann's piece is the sound shadow cast when<br />

a silently struck piano string vibrates sympathetically.<br />

This effect reveals the gap between the façade of<br />

sound, the outspokenness of the struck key, and its<br />

inner life.<br />

In Manualenes poesi Christian Blom uses the same<br />

effect to conceal the poetic core of the music behind<br />

a wall of staccato clusters. Of course, the clusters in<br />

the foreground are themselves musical and not just a<br />

disturbance, they are dry and hard and without<br />

humour. The chords that sound sympathetically are<br />

made possible by this façade of sounds in the first<br />

place. Still the essence of the music does not unfold in<br />

the forefront, it has been moved to the periphery of not<br />

only the instrument, but of the listening radius<br />

altogether. "Do you understand?" he asks the pianist<br />

when the second part, a Satie-like arrangement of<br />

chords, begins. "Understand" that the keys that are<br />

now struck correspond with the ghost sounds from<br />

the first part. When Jacques Derrida developed the<br />

idea of “hauntology” he was not thinking about music.<br />

Yet the idea of a haunting of ideas and sounds<br />

undercutting the musical present has been adapted<br />

by many com<br />

decade. The li<br />

also means that<br />

to put it solemn<br />

It is not alwa<br />

interesting let a<br />

Among the gho<br />

the haunting vo<br />

exposed to. It i<br />

driven mad by m<br />

the Imaginary<br />

regions of soun<br />

listener (for th<br />

preludes the sc<br />

describing the<br />

4

ynade as an<br />

usical gesture<br />

be used in an<br />

of course yes,<br />

e proved. Yet<br />

t further and<br />

s directing his<br />

the instrument,<br />

ce within the<br />

s central to<br />

ow cast when<br />

ympathetically.<br />

the façade of<br />

ck key, and its<br />

uses the same<br />

music behind<br />

the clusters in<br />

l and not just a<br />

and without<br />

athetically are<br />

ds in the first<br />

es not unfold in<br />

eriphery of not<br />

tening radius<br />

sks the pianist<br />

rrangement of<br />

keys that are<br />

t sounds from<br />

developed the<br />

g about music.<br />

s and sounds<br />

been adapted<br />

by many composers and artists within the last<br />

decade. The listening of elsewhere and elsewhen<br />

also means that we are shifting perspectives, that we,<br />

to put it solemnly, are pushing frontiers.<br />

It is not always the loudest who are the most<br />

interesting let alone the most intelligent to listen to.<br />

Among the ghosts of the past we most certainly find<br />

the haunting voices of the Sirens that Ulysses was<br />

exposed to. It is, of course, an aspiring claim to be<br />

driven mad by music. Christian Jaksjø's Encountering<br />

the Imaginary [Ulysses] is an attempt to access<br />

regions of sound that have been withdrawn from the<br />

listener (for the sake of his own safety). Jaksjø<br />

preludes the score with a text by Maurice Blanchot,<br />

describing the song of the Sirens as unfulfilling yet<br />

being "a sign of where the real sources and real<br />

happiness of song opened", and the text seems like an<br />

antedated description of Jaksjø's piece, in which the<br />

instrument is engaged in a self-modulating song<br />

through an elaborate electro-acoustic exchange<br />

between the played piano part and an electronic<br />

soundtrack. There is also a close connection between<br />

Jaksjø's Encountering the Imaginary and<br />

Lachenmann's Serynade, the material of the former<br />

having been derived from the latter, exposing those<br />

sounds that Lachenmann only hinted at. But more<br />

than being a frottage of Lachenmann's piece Jaksjø<br />

has tapered the project of listening deeply and<br />

beyond, turning the piano into a guidepost that leads<br />

well into the 21st century.<br />

5

CHRISTIAN BLOM<br />

Manualenes poesi (2007–11) for klaver<br />

HELMUT LACHENMANN<br />

Serynade (1998/2000) for klaver<br />

CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ<br />

Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses] (2009/10)<br />

for ringmodulert elektromekanisk forsterket klaver<br />

og elektronisk lyd<br />

Når blir klaveret til et klaver? Utelukkende når en<br />

stor virtuos framfører Chopins Revolusjonsetyde på<br />

det, feilfritt og imponerende? Hva hvis pianisten bare<br />

gnir fingerneglene sine langs tangentene med en<br />

skrapende lyd? Hva med pianisten som dunker på<br />

treet i instrumentkroppen? Hva med pianisten som<br />

ikke spiller overhodet?<br />

—<br />

AV BJÖRN GOTTSTEIN<br />

—<br />

Fram til midten av det 20. århundre er klaveret blitt spilt<br />

på og lyttet til med en sikkerhet som avantgarden<br />

deretter forstyrret. En komponist som vil skrive for<br />

klaver i dag, må forholde seg til at det å trykke ned<br />

tangenter bare er en av mange muligheter. Likevel<br />

forventes det at pianisten i Helmut Lachenmanns verk<br />

Serynade også kan behandle instrumentet innenfor<br />

konvensjonelle<br />

som er gitt a<br />

konflikten mello<br />

borgerlig selvfo<br />

laboratorium fo<br />

utvikling på den<br />

på innsiden av<br />

tids musikk for k<br />

stykkene Lache<br />

fram enkeltstå<br />

som den skra<br />

isolasjonen av u<br />

Ein Kinderspiel<br />

Serynade er fa<br />

Lachenmann sk<br />

lettere musikk fr<br />

slekt med form<br />

(Den feilstaven<br />

som verket er<br />

lette og frie finn<br />

fra de dype til<br />

show-off, en ge<br />

materiale; den<br />

forsøk på å børs<br />

med, er hva som<br />

framkaller. Næ<br />

Lachenmann be<br />

plassert i en sa<br />

teknisk sett ikke<br />

han tilsynelate<br />

Schönberg stilt<br />

komponister til<br />

«Ja, men lager<br />

6

10)<br />

aver<br />

averet blitt spilt<br />

avantgarden<br />

vil skrive for<br />

t å trykke ned<br />

gheter. Likevel<br />

enmanns verk<br />

ntet innenfor<br />

konvensjonelle rammer. Den historiske dialektikken<br />

som er gitt av klaveret selv, den uomgjengelige<br />

konflikten mellom å være et dyrt møbel som bekrefter<br />

borgerlig selvforståelse på den ene siden, og et<br />

laboratorium for klanglige eksperimenter og estetisk<br />

utvikling på den andre, er umulig å løse. Det er snarere<br />

på innsiden av denne konflikten at mulighetene i vår<br />

tids musikk for klaver utfolder seg. Mange av de tidlige<br />

stykkene Lachenmann har skrevet for klaver, viser<br />

fram enkeltstående egenskaper ved instrumentet,<br />

som den skrapende lyden i Guero (1970) eller<br />

isolasjonen av ulike parametre og filtreringseffekter i<br />

Ein Kinderspiel (1980).<br />

Serynade er faktisk det første verket i stor skala<br />

Lachenmann skrev for klaver solo. Tittelen henviser til<br />

lettere musikk framført utendørs og/eller om kvelden, i<br />

slekt med former som ständchen og divertimento.<br />

(Den feilstavende «y»-en i tittelen viser til utøveren<br />

som verket er tilegnet, Yukiko Sugawara.) Både det<br />

lette og frie finnes virkelig i dette stykket. Glissandoen<br />

fra de dype til de lyse tangentene nærmer seg en<br />

show-off, en gest det er vanskelig å ta alvorlig som<br />

materiale; den uttrykker ikke annet enn et dristig<br />

forsøk på å børste noe vekk. Spørsmålet vi sitter igjen<br />

med, er hva som hender med musikken Lachenmann<br />

framkaller. Nær sagt alle figurer og teknikker<br />

Lachenmann benytter seg av, er allerede utforsket og<br />

plassert i en sammenheng. Slikt sett oppfinner han<br />

teknisk sett ikke noe nytt. I stedet minner spørsmålet<br />

han tilsynelatende stiller, om spørsmålet Arnold<br />

Schönberg stilte da han ble fortalt at mange unge<br />

komponister tilegnet seg tolvtoneteknikkene hans:<br />

«Ja, men lager de også musikk?»<br />

Man kan lytte til Lachenmanns Serynade som et<br />

essay i å uttrykke seg musikalsk. Kan en musikalsk<br />

gest som er ladet med mening, fortsatt brukes på en<br />

måte som vil bli oppfattet som original og ekte?<br />

Svaret er selvsagt ja, og 600 år med musikk for<br />

tangentinstrumenter beviser det. Likevel peker<br />

Lachenmann tilsynelatende videre, stadig lengre inn i<br />

klaveret, som om han leder sin musikalske fantasi inn<br />

i instrumentets innerste hjørner, på jakt etter rester av<br />

resonans inne i det vibrerende treet. En sentral figur i<br />

Lachenmanns stykke er skyggen lyden kaster når en<br />

av strengene i klaveret vibrerer sympatisk eller<br />

passivt, kun satt i bevegelse av vibrasjonen i de andre<br />

strengene. Denne effekten avslører avstanden<br />

mellom lydens fasade, selve det uttalte ved tangenten<br />

som blir slått an, og lydens indre liv.<br />

I Manualenes poesi bruker Christian Blom samme<br />

effekt til å skjule en poetisk kjerne i musikken bak en<br />

vegg av staccato clustre. Selvfølgelig er clustrene i<br />

forgrunnen også musikalske og ikke bare der for å<br />

forstyrre, de er tørre, harde og blottet for humor.<br />

Akkordene som klinger passivt hadde ikke vært<br />

mulige uten denne fasaden av lyd i første omgang.<br />

Likevel utfolder ikke det essensielle i denne musikken<br />

seg i forgrunnen, det er flyttet til utkanten, ikke bare av<br />

instrumentet, men av lyttingens radius overhodet.<br />

«Forstår du?» spør han pianisten, når annen del, et<br />

Satie-aktig arrangement av akkorder, begynner.<br />

«Forstår» at tangentene nå trykkes ned i samsvar med<br />

de spektrale klangene fra første del. Da Jacques<br />

Derrida utviklet begrepet om hauntology (av «haunt»,<br />

å hjemsøke), tenkte han ikke på musikk. Likevel har<br />

tanken om å sette ideer og lyder på prøve, på en måte<br />

7

What was the n<br />

its fault lie? Wh<br />

Some have alw<br />

song–a natural<br />

kinds?), but on<br />

possible way to<br />

that extreme de<br />

the normal con<br />

enchantment w<br />

reproduce the h<br />

som undergraver et musikalsk nå, blitt adoptert av<br />

mange komponister og kunstnere de siste ti årene. Å<br />

lytte annensteds og i en annen tid innebærer også at<br />

perspektivet skifter, at vi, for å si det høytidelig, flytter<br />

grenser.<br />

Det kraftigste er ikke alltid det mest interessante eller<br />

intelligente å lytte til. Sirenenes stemmer som<br />

hjemsøkte Ulysses, er utvilsomt skygger fra fortiden.<br />

De styrker ideen om at musikk kan drive mennesket<br />

fra forstanden. Christian Jaksjøs Encountering the<br />

Imaginary [Ulysses] prøver å skape tilgang til<br />

klanglige områder som er blitt unndratt lytteren (av<br />

sikkerhetshensyn). Som innledning til partituret har<br />

Jaksjø en tekst av Maurice Blanchot der sirenenes<br />

sang blir beskrevet som utilfredsstillende og samtidig<br />

«et tegn på hvor sangens virkelige kilder og gleder<br />

åpnet seg», og teksten virker som om den foregriper<br />

en beskrivelse av Jaksjøs stykke, der instrumentet<br />

engasjeres i en selvmodulerende sang gjennom en<br />

elektroakustisk utveksling mellom klaverstemmen og<br />

det elektroniske lydsporet. Det er også en nær<br />

sammenheng mellom Jaksjøs Encountering the<br />

Imaginary og Lachenmanns Serynade, i og med at<br />

materialet i det førstnevnte er utvunnet fra det<br />

sistnevnte og stiller ut de klangene som Lachenmann<br />

bare antydet eksistensen av. Men mer enn å være en<br />

overtegning av Lachenmanns verk, har Jaksjø<br />

fortsatt å gradbøye den dype lyttingen videre, og har<br />

gjort klaveret til en utkikkspost med utsikt langt inn i<br />

det 21. århundre.<br />

Enc<br />

The Sirens: it s<br />

unfulfilling way,<br />

real sources an<br />

by means of th<br />

song still to com<br />

space where s<br />

deceive him, in<br />

But what happ<br />

What was this<br />

left but to disap<br />

source and o<br />

completely than<br />

where, ears blo<br />

Sirens, as proof<br />

disappear.<br />

8

lder og gleder<br />

den foregriper<br />

r instrumentet<br />

g gjennom en<br />

erstemmen og<br />

også en nær<br />

ountering the<br />

e, i og med at<br />

unnet fra det<br />

Lachenmann<br />

enn å være en<br />

, har Jaksjø<br />

videre, og har<br />

tsikt langt inn i<br />

Encountering the Imaginary<br />

The Sirens: it seems they did indeed sing, but in an<br />

unfulfilling way, one that only gave a sign of where the<br />

real sources and real happiness of song opened. Still,<br />

by means of their imperfect songs that were only a<br />

song still to come, they did lead the sailor toward that<br />

space where singing might truly begin. They did not<br />

deceive him, in fact: they actually led him to his goal.<br />

But what happened once the place was reached?<br />

What was this place? One where there was nothing<br />

left but to disappear, because music, in this region of<br />

source and origin, had itself disappeared more<br />

completely than in any other place in the world: sea<br />

where, ears blocked, the living sank, and where the<br />

Sirens, as proof of their good will, had also, one day, to<br />

disappear.<br />

What was the nature of the Sirens’ song? Where did<br />

its fault lie? Why did this fault make it so powerful?<br />

Some have always answered: It was an inhuman<br />

song–a natural noise no doubt (are there any other<br />

kinds?), but on the fringes of nature, foreign in every<br />

possible way to man, very low, and awakening in him<br />

that extreme delight in falling that he cannot satisfy in<br />

the normal conditions of life. But, say others, the<br />

enchantment was stranger than that: it did nothing but<br />

reproduce the habitual song of men, and because the<br />

Sirens, who were only animals, quite beautiful<br />

because of the reflection of feminine beauty, could<br />

sing as men sing, they made the song so strange that<br />

they gave birth in anyone who heard it to a suspicion<br />

of the inhumanity of every human song. Is it through<br />

despair, then, that men passionate for their own song<br />

came to perish? Through a despair very close to<br />

rapture. There was something wonderful in this real<br />

song, this common, secret song, simple and everyday,<br />

that they had to recognize right away, sung in an<br />

unreal way by foreign, even imaginary powers, song<br />

of the abyss that, once heard, would open an abyss in<br />

each word and would beckon those who heard it to<br />

vanish into it.<br />

This song, we must remember, was aimed at sailors,<br />

men who take risks and feel bold impulses, and it was<br />

also a means of navigation: it was a distance, and it<br />

revealed the possibility of traveling this distance, of<br />

making the song into the movement toward the song,<br />

and of making this movement the expression of the<br />

greatest desire. Strange navigation, but toward what<br />

end? It has always been possible to think that those<br />

who approached it did nothing but come near to it, and<br />

died because of impatience, because they<br />

prematurely asserted: here it is; here, here I will cast<br />

9

anchor. According to others, it was on the contrary too<br />

late: the goal had already been passed; the<br />

enchantment, by an enigmatic promise, exposed men<br />

to being unfaithful to themselves, to their human song<br />

and even to the essence of the song, by awakening<br />

the hope and desire for a wonderful beyond, and this<br />

beyond represented only a desert, as if the<br />

motherland of music were the only place completely<br />

deprived of music, a place of aridity and dryness<br />

where silence, like noise, burned, in one who once<br />

had the disposition for it, all passageways to song.<br />

Was there, then, an evil principle in this invitation to<br />

the depths? Were the Sirens, as tradition has sought<br />

to persuade us, only the false voices that must not be<br />

listened to, the trickery of seduction that only disloyal<br />

and deceitful beings could resist?<br />

There has always been a rather ignoble effort among<br />

men to discredit the Sirens by flatly accusing them of<br />

lying: liars when they sang, deceivers when they<br />

sighed, fictive when they were touched; in every<br />

respect nonexistent, with a childish nonexistence that<br />

the good sense of Ulysses was enough to exterminate.<br />

treachery which led him to enjoy the entertainment of<br />

the Sirens, without risks and without accepting the<br />

consequences; his was a cowardly, moderate, and<br />

calm enjoyment, as befits a Greek of the decadent era<br />

who will never deserve to be the hero of the Iliad. His<br />

is a fortunate and secure cowardliness, based on<br />

privilege, which places him outside of the common<br />

condition–others having no right to the happiness of<br />

the elite, but only a right to the pleasure of watching<br />

their leader writhe ridiculously, with grimaces of<br />

ecstasy in the void, a right also to the satisfaction of<br />

mastering their master (that is no doubt the lesson<br />

they understood, the true song of the Sirens for them).<br />

Ulysses’ attitude, that surprising deafness of one who<br />

is deaf because he is listening, is enough to<br />

communicate to the Sirens a despair reserved till now<br />

for humans and to turn them, through this despair, into<br />

actual beautiful girls, real this one time only and<br />

worthy of their promise, thus capable of disappearing<br />

into the truth and profundity of their song.<br />

«Maurice Blanchot: The Book to Come»<br />

(Translated by Charlotte Mandell. Courtesy of Stanford University Press)<br />

It is true, Ulysses conquered them, but in what way?<br />

Ulysses, with his stubbornness and prudence, his<br />

10

tertainment of<br />

accepting the<br />

moderate, and<br />

e decadent era<br />

of the Iliad. His<br />

ess, based on<br />

f the common<br />

e happiness of<br />

re of watching<br />

grimaces of<br />

satisfaction of<br />

ubt the lesson<br />

irens for them).<br />

ss of one who<br />

is enough to<br />

served till now<br />

is despair, into<br />

time only and<br />

f disappearing<br />

g.<br />

»<br />

University Press)<br />

11

Christian Blom (1974) is an artist living on<br />

Nesoddtangen. He works with kinetic sculpture,<br />

mechanical devices and composition. Blom has a formal<br />

background as a guitarist and composer, counting a<br />

cand. philol in composition from the University of Bergen<br />

as a current academic highlight. Blom is constantly<br />

researching the parallells and differences in different<br />

media and their techniques. In particular on search for<br />

unexpected connections and perspectives.<br />

www.christianblom.com<br />

Christian Jaksjø’s musical background includes<br />

studies of improvisation, composition, and<br />

electro-acoustic music, an extensive performing<br />

career on trombone, euphonium, and related<br />

instruments, interdiciplinary experimental studies of<br />

dynamic form with architects, designers and<br />

engineers, along with a concurrent, groundbreaking<br />

creative practice as a composer: utilizing, for instance,<br />

processual musical transformation by means of<br />

discretely varying virtual n-tone equal-tempered<br />

divisions of the octave (Orthodrom/Loxodrom<br />

[Grosszirkelnavigation], 1997–2000); architecturized<br />

music composed algorithmically by means of complex<br />

dynamical systems operating directly on<br />

architectonical spatial structures by Jan Duiker<br />

(Ungrounded [Zonnestraal], 2002); stochastic<br />

algorithmic composition and sound synthesis directly<br />

operating on mystical texts by David Libeskind (The<br />

Four Texts, 2003) or also on the virtual instrumental<br />

resonance occurring in Helmut Lachenmann’s<br />

Serynade, and in the latter case combined with<br />

complex instrumental extension by means of ring<br />

Christian Blom (1974) er bosatt på Nesoddtangen.<br />

Han arbeider med kinetiske skulpturer, mekaniske<br />

innretninger og komposisjon. Blom har formell<br />

bakgrunn som gitarist og komponist med cand.<br />

philol i komposisjon fra Universitetet i Bergen som<br />

foreløpig akademisk høydepunkt. I sine prosjekter<br />

utforsker Blom forbindelser mellom ulike medier og<br />

deres teknikker. Med særlig blikk på uventede<br />

forbindelser og perspektiver.<br />

www.christianblom.com<br />

Christian Jaksjøs musikalske bakgrunn inkluderer<br />

studier i improvisasjon, komposisjon og<br />

elektroakustisk musikk, en omfattende karriere som<br />

utøver på trombone, euphonium og beslektede<br />

instrumenter, interdisiplinære eksperimentelle studier<br />

av dynamisk form med arkitekter, designere og<br />

ingeniører, ved siden av parallelt, banebrytende<br />

kreativt virke som komponist, uttrykt f.eks. gjennom:<br />

prosessuell musikalsk transformasjon ved hjelp av<br />

diskret varierende virtuelle n-toners tempereringer<br />

(Orthodrom/Loxodrom [Großzirkelnavigation],<br />

1997–2000); arkitektifisert musikk komponert<br />

algoritmisk ved hjelp av komplekse dynamiske<br />

systemer som opererer direkte på arkitektoniske<br />

romlige strukturer av Jan Duiker (Ungrounded<br />

[Zonnestraal], 2002); stokastisk algoritmisk<br />

komposisjon og lydsyntese som opererer direkte på<br />

mystiske tekster av David Libeskind (The Four Texts,<br />

2003), eller også på den virtuelle<br />

instrumentalresonansen slik den forekommer i Helmut<br />

Lachenmanns Serynade, og i dette tilfelle kombinert<br />

med en kompleks instrumental utvidelse ved hjelp av<br />

modulated elect<br />

feedback (Enco<br />

2009–2010). Pivo<br />

and as an impro<br />

forces as well a<br />

Christian Jaksjø<br />

was born in 197<br />

since 2003, play<br />

www.christianja<br />

Helmut Lachenm<br />

influential Europ<br />

early 21st centu<br />

Venice and Colo<br />

Beginning in the<br />

new and innova<br />

as temA (1968),<br />

(1969), for orche<br />

instruments and<br />

new sounds and<br />

instruments we<br />

questions past m<br />

postserialist com<br />

writings.<br />

Other works inc<br />

(1972), Accanto<br />

Estarrung) (1984<br />

(1984/85), Allegr<br />

for piano, and th<br />

A well-known te<br />

mentor to many<br />

12

soddtangen.<br />

, mekaniske<br />

r formell<br />

ed cand.<br />

Bergen som<br />

e prosjekter<br />

ike medier og<br />

ventede<br />

modulated electromechanical and electromagnetical<br />

feedback (Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses],<br />

2009–2010). Pivotal to his work, both as a composer<br />

and as an improviser, is rendering audible: underlying<br />

forces as well as otherwise imperceptible patterns.<br />

Christian Jaksjø lives and works in Oslo (where he<br />

was born in 1973) and in Frankfurt am Main (where he,<br />

since 2003, plays trombone in the hr-Bigband).<br />

www.christianjaksjø.no<br />

ringmodulert elektromekanisk og elektromagnetisk<br />

tilbakekobling (Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses],<br />

2009-10). Sentralt i hans virke, både som<br />

improviserende musiker og som komponist, er å gjøre<br />

hørbart: såvel bakenforliggende krefter som ellers<br />

uhørlige mønstre. Christian Jaksjø bor og arbeider i<br />

Oslo (hvor han ble født i 1973) og i Frankfurt am Main<br />

(hvor han, siden 2003, spiller trombone i hr-Bigband).<br />

www.christianjaksjø.no<br />

inkluderer<br />

karriere som<br />

lektede<br />

entelle studier<br />

nere og<br />

rytende<br />

ks. gjennom:<br />

ed hjelp av<br />

pereringer<br />

ation],<br />

nert<br />

amiske<br />

ektoniske<br />

unded<br />

isk<br />

er direkte på<br />

e Four Texts,<br />

mmer i Helmut<br />

lle kombinert<br />

e ved hjelp av<br />

Helmut Lachenmann (1935) is one of the most<br />

influential European composers of the late 20th and<br />

early 21st centuries. He studied with Luigi Nono in<br />

Venice and Cologne.<br />

Beginning in the late 1960s, Lachenmann explored a<br />

new and innovative musical language. In works such<br />

as temA (1968), for flute, voice and cello, and Air<br />

(1969), for orchestra and percussion soloist, he used<br />

instruments and voices unconventionally, producing<br />

new sounds and sound combinations in which all<br />

instruments were given equal weight. Lachenmann<br />

questions past musical assumptions in his many<br />

postserialist compositions and in his varied musical<br />

writings.<br />

Other works include the string quartet Gran Torso<br />

(1972), Accanto (1975/76), Mouvement (vor der<br />

Estarrung) (1984) for chamber orchestra, Ausklang<br />

(1984/85), Allegro Sostenuto (1986/88), Serynade (2000)<br />

for piano, and the opera The Little Match Girl (2001).<br />

A well-known teacher, Lachenmann has been a<br />

mentor to many important younger composers.<br />

Helmut Lachenmann (1935) er en av Europas mest<br />

innflytelsesrike komponister i det sene 20. og tidlige<br />

21. århundre. Han studerte med Luigi Nono i Venezia<br />

og i Köln.<br />

Mot slutten av 1960-årene begynte Lachenmann å<br />

utforske et helt nytt musikalsk språk. I verk som temA<br />

(1968), for fløyte, stemme og cello, og Air (1969), for<br />

orkester og solo slagverk, brukte han både<br />

instrumenter og stemmer på en ukonvensjonell måte,<br />

hvilket resulterte i nye klanger og klangkombinasjoner<br />

der samtlige instrumenter hadde likeverdige stemmer.<br />

Lachenmann setter spørsmålstegn ved tidligere<br />

musikalske antagelser i sine mange postserialistiske<br />

komposisjoner og artikler.<br />

På hans verkliste er bl.a. strykekvartetten Gran Torso<br />

(1972), Accanto (1975/76), Mouvement (vor der<br />

Estarrung) (1984) for kammerorkester, Ausklang<br />

(1984/85), Allegro Sostenuto (1986/88), Serynade (2000)<br />

for piano, og operaen Piken med svovelstikkene<br />

(2001). Lachenmann er også en høyt skattet lærer og<br />

mentor for unge komponister.<br />

13

Ellen Ugelvik c<br />

performing new<br />

composers. Sh<br />

the Grieg Acad<br />

Conservatorium<br />

Schleiermache<br />

Theater, Leipzig<br />

Ugelvik works a<br />

Europe, USA an<br />

festivals such a<br />

Internationalen<br />

Darmstadt, Ultra<br />

Huddersfield Co<br />

Muziekweek, M<br />

Nachts, Ultima C<br />

Borealis, ILIOS,<br />

Monday Evenin<br />

composers inclu<br />

Fujikura, Magne<br />

Jaksjø, Michael<br />

Birkelund, Claus<br />

Steen-Andersen<br />

Gadenstätter, H<br />

Ingvar Lidholm,<br />

Gjertsen.<br />

Her commitmen<br />

recognised. Sh<br />

performing arti<br />

in Norway. Her<br />

rewarded with<br />

member of the<br />

and Polygon.<br />

14

Ellen Ugelvik concentrates on discovering and<br />

performing new works by contemporary<br />

composers. She has studied with Einar Røttingen at<br />

the Grieg Academy in Bergen, Håkon Austbø at the<br />

Conservatorium van Amsterdam and Steffen<br />

Schleiermacher at the Hochschule für Musik und<br />

Theater, Leipzig.<br />

Ugelvik works as a soloist and chamber musician in<br />

Europe, USA and Asia. She has been invited to<br />

festivals such as Tasten – Berliner Klaviertage,<br />

Internationalen Ferienkurse für Neue Musik<br />

Darmstadt, Ultraschall, Gaudeamus, Rainy Days,<br />

Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, De Suite<br />

Muziekweek, Musik der Jahrhunderte; Südseite<br />

Nachts, Ultima Contemporary Music Festival,<br />

Borealis, ILIOS, Risør Festival of Chamber Music, and<br />

Monday Evening Concerts. She collaborates with<br />

composers including Helmut Lachenmann, Dai<br />

Fujikura, Magne Hegdal, Christian Blom, Christian<br />

Jaksjø, Michael Finnissy, Unsuk Chin, Therese<br />

Birkelund, Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf, Simon<br />

Steen-Andersen, Sven Lyder Kahrs, Clemens<br />

Gadenstätter, Helmut Oehring, Trond Reinholdtsen,<br />

Ingvar Lidholm, Nicholas A. Huber and Ruben S.<br />

Gjertsen.<br />

Her commitment to contemporary music is widely<br />

recognised. She recently received a state grant for<br />

performing artists, one of the most coveted awards<br />

in Norway. Her first solo album, Makrokosmos was<br />

rewarded with the Norwegian Grammy. She is a<br />

member of the ensembles asamisimasa, Jagerflygel<br />

and Polygon.<br />

Ellen Ugelvik er utdannet ved Konservatoriet i<br />

Amsterdam, Musikkhøyskolen i Leipzig og<br />

Griegakademiet i Bergen med Håkon Austbø,<br />

Steffen Schleiermacher og Einar Røttingen som<br />

veiledere.<br />

Ugelvik har fordypet seg i fremføring av<br />

samtidsmusikk og konserterer som solist og<br />

kammermusiker over hele verden. Hun har deltatt<br />

på samtidsmusikkfestivaler som Tasten – Berliner<br />

Klaviertage, Internationalen Ferienkurse für Neue<br />

Musik Darmstadt, Ultraschall, Gaudeamus, Rainy<br />

Days, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival,<br />

De Suite Muziekweek, Musik der Jahrhunderte;<br />

Südseite Nachts, Ultima, Borealis, ILIOS, Risør<br />

Kammermusikkfest og Monday Evening Concerts.<br />

Ellen Ugelvik har bestilt og uroppført en rekke<br />

verker og samarbeider med komponister som<br />

Helmut Lachenmann, Dai Fujikura, Magne Hegdal,<br />

Christian Blom, Christian Jaksjø, Michael Finnissy,<br />

Unsuk Chin, Therese Birkelund, Claus-Steffen<br />

Mahnkopf, Simon Steen-Andersen, Sven Lyder<br />

Kahrs, Clemens Gadenstätter, Helmut Oehring,<br />

Ingvar Lidholm, Nicholas A. Huber og Ruben S.<br />

Gjertsen.<br />

Hun har vært solist med de største orkestrene og<br />

ensemblene i Norge med bl.a. Helmut Lachenmanns<br />

klaverkonsert Ausklang, hvor hennes fremføring ble<br />

nominert til Kritikerprisen. Hennes første<br />

soloutgivelse Makrokosmos ble premiert med<br />

Spellemannprisen. Hun er medlem av ensemblene<br />

asamisimasa, Jagerflygel og Polygon.<br />

15

Norwegian Spellemann Prize 2008<br />

… the way the Ugelvik has so completely absorbed<br />

the required idiom make concentrated listening to<br />

Makrokosmos on the sensitively-recorded SACD a<br />

spell-binding experience. Ugelvik's [recording] must<br />

now be considered a worthy front-runner.<br />

[MusicWeb / Mark Sealy]<br />

– Ugelvik spiller fantastisk flott, jeg tror ikke stykkene<br />

kan spilles bedre. Dette er en plate jeg kommer til<br />

å høre igjen og igjen.<br />

[6/6 Erik Steinskog, Bergens Tidende]<br />

17

Serynade<br />

Recorded 8-10 N<br />

Producer: Tony<br />

Engineer: Geoff<br />

Editor: Stephen<br />

Steinway Grand<br />

Encountering th<br />

Recorded 30-31<br />

Producer, engin<br />

Technical super<br />

Bösendorfer 22<br />

Liner notes: Bjö<br />

Translation: Hild<br />

Cover design: M<br />

Photo: Observa<br />

Executive produ<br />

The poetry of m<br />

Norsk kulturråd<br />

©&π 2012 Norwegian<br />

All trademarks and log<br />

and of the owner of th<br />

copying, hiring, lending<br />

of this record prohibite<br />

Released with s<br />

18

Serynade<br />

Recorded 8-10 November 2009 in Sofienberg church, Oslo<br />

Producer: Tony Harrison<br />

Engineer: Geoff Miles<br />

Editor: Stephen Frost<br />

Steinway Grand Model D, technician Thron Irby<br />

Encountering the Imaginary and The poetry of manuals<br />

Recorded 30-31 May and 1 June 2011 in Vestfossen church<br />

Producer, engineer and editor: Sean Lewis<br />

Technical supervision electro-acoustics: Christian Jaksjø<br />

Bösendorfer 225, technician Tore Poulsen/Aspheim<br />

Liner notes: Björn Gottstein<br />

Translation: Hild Borchgrevink<br />

Cover design: Martin Kvamme<br />

Photo: Observatoriet<br />

Executive producer: Erik Gard Amundsen<br />

Released with support from: Norsk kulturråd and Norsk komponistforening<br />

The poetry of manuals and Encountering the Imaginary are commissioned by Ellen Ugelvik with support from<br />

Norsk kulturråd<br />

©&π 2012 Norwegian Society of Composers<br />

All trademarks and logos are protected. All rights of the producer<br />

and of the owner of the work reproduced reserved. Unauthorized<br />

copying, hiring, lending, public performance and broadcasting<br />

of this record prohibited. NOLFA1261010-030 · ACD5061 Stereo<br />

19

Serynade<br />

1. CHRISTIAN BLOM<br />

The poetry of manuals<br />

— 13:01<br />

—<br />

2. HELMUT LACHENMANN<br />

Serynade<br />

— 23:12<br />

—<br />

3. CHRISTIAN JAKSJØ<br />

Encountering the Imaginary [Ulysses]<br />

– for ring modulated electromechanically amplified piano and electronic sound<br />

— 24:00<br />

—<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

Serynade<br />

7044581350614<br />

π&© 2012 NORWEGIAN SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS<br />

NOLFA1261010-030 · ACD 5061 · STEREO · TT 60:16<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

ACD 5061<br />

<strong>ELLEN</strong> <strong>UGELVIK</strong>, <strong>PIANO</strong><br />

ACD 5061