The Tomb of Sataimau at Hagr Edfu: An overview - British Museum

The Tomb of Sataimau at Hagr Edfu: An overview - British Museum

The Tomb of Sataimau at Hagr Edfu: An overview - British Museum

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

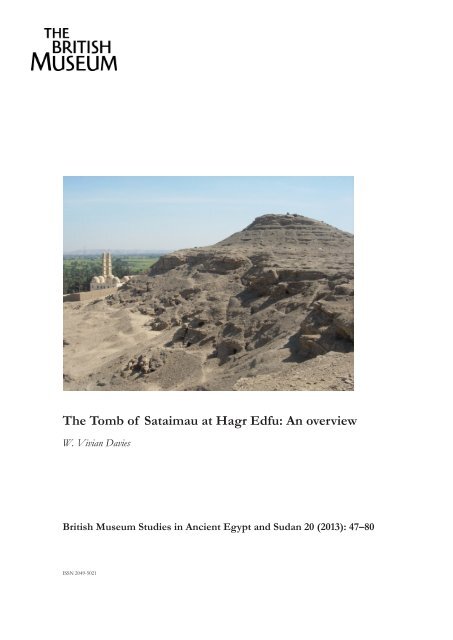

picture <strong>at</strong> 50mm from top<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tomb</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>: <strong>An</strong> <strong>overview</strong><br />

W. Vivian Davies<br />

<strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Studies in <strong>An</strong>cient Egypt and Sudan 20 (2013): 47–80<br />

ISSN 2049-5021

<strong>The</strong> tomb <strong>of</strong> <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>: <strong>An</strong> <strong>overview</strong><br />

W. Vivian Davies<br />

Introduction 1<br />

Notable among the pharaonic monuments in the necropolis <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> (Fig. 1) is a<br />

group <strong>of</strong> three tombs loc<strong>at</strong>ed <strong>at</strong> the foot <strong>of</strong> the main hill <strong>of</strong> the site (Figs 2–3). <strong>The</strong>y were<br />

uncovered by the Egyptian <strong>An</strong>tiquities Service in 1941 (see Fakhry 1947, 47–48; Gabra 1977,<br />

208–11; Effland 1999, 25–26; Effland et al. 1999, 40–53) and have been the subject <strong>of</strong> recent<br />

detailed document<strong>at</strong>ion by a <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> expedition. <strong>The</strong>ir loc<strong>at</strong>ion, close to the western<br />

enclosure wall <strong>of</strong> the Monastery <strong>of</strong> Pachomios, a modern monastery built on the site <strong>of</strong><br />

ancient predecessors (the earliest <strong>of</strong> these possibly an Egyptian temple; see Sauneron 1958,<br />

278–79, n. 3; Effland 1999, 30), is shown on the expedition’s new map <strong>of</strong> the site (Fig. 4).<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the tombs belongs to a high <strong>of</strong>ficial named <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> and is d<strong>at</strong>ed by inscription<br />

to the reign <strong>of</strong> King Amenhotep I. <strong>The</strong> two others were left undecor<strong>at</strong>ed by their original<br />

owners but bear a large number <strong>of</strong> secondary motifs and inscriptions (see Effland et al.<br />

1999, 42–45, 65–66, figs 1–3; Davies 2006, 134, 140, fig. 4, 146, pl. 4; Davies and O’Connell<br />

2009, 54, 64, fig. 8; Davies et al. 2011a, 37–38, 54, pl. viii, b; 2011b, 59, 68, pl. iii, b). <strong>The</strong>se<br />

unfinished tombs, repurposed over time, became places <strong>of</strong> destin<strong>at</strong>ion, oper<strong>at</strong>ing already in<br />

Dynasty 18 as shrines or small temples dedic<strong>at</strong>ed to the worship <strong>of</strong> the local gods (see Davies<br />

2010, 130, 135, fig. 6; Davies and O’Connell 2011a, 105; O’Connell 2010, 5; Davies and<br />

O’Connell 2012, 55). <strong>The</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> supplicants is also recorded in motifs and inscriptions,<br />

d<strong>at</strong>ing probably from the Old Kingdom onwards, carved into the rock on the top <strong>of</strong> the<br />

main hill (see Davies 2006, 134, 148–49, pls vi–vii; Davies and O’Connell 2009, 56, 72, figs<br />

21–22; Davies and O’Connell 2011b, 6, 28–29, figs 32–34; Davies and O’Connell 2012, 55;<br />

82, figs 34–35; Davies et al. 2011b, 63, 72, pl. vii, a–b). <strong>The</strong> evidence suggests th<strong>at</strong> during the<br />

pharaonic period <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> not only served as an elite necropolis but was regarded as a holy<br />

mound (i3t), a ‘heilige Bezirk,’ sacred to the <strong>Edfu</strong> triad (Horus Behdety, H<strong>at</strong>hor and Isis) and<br />

integral to the wider ritual land- and w<strong>at</strong>erscape centred on the temple <strong>of</strong> Horus Behdety in<br />

<strong>Edfu</strong> (Fig. 1); it may have been the site <strong>of</strong> the original Behdet, which appears l<strong>at</strong>er to have<br />

been centred to the south in the area <strong>of</strong> Nag‘ el-Hissaya (see Alliot 1954, 551, n. 2; Gabra<br />

1977, 221–22; Kurth 1994, 95–99 with n. 13; Egberts 1995, 15, n. 9; Egberts 1998, 799–801;<br />

Effland 1999, 27; Effland et al. 1999, 40, 43; Kurth 1999, 269; Effland and Graeff 2010; for<br />

recent investig<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the evolving w<strong>at</strong>erscape, see Bunbury et al. 2009; Davies et al. 2011a,<br />

36, 44–46; 2011b, 63–65, 73, pl. viii).<br />

A ground-plan <strong>of</strong> the group is reproduced in Fig. 5. <strong>The</strong> tomb <strong>of</strong> <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>, HE <strong>Tomb</strong><br />

1, is th<strong>at</strong> on the left (the southernmost). In the middle, almost identical in size and plan and<br />

possibly contemporary with HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, is HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 2. On the right, much larger than the<br />

1<br />

This paper, an up-d<strong>at</strong>ed version <strong>of</strong> Davies 2009 (in French), will be included in a forthcoming volume<br />

containing reports on various aspects <strong>of</strong> the <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> expedition’s work <strong>at</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

49<br />

others and more elabor<strong>at</strong>e in plan (and with an open substructure), is HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 3, which<br />

probably d<strong>at</strong>es originally to the Middle Kingdom, possibly to l<strong>at</strong>er Dynasty 12 (as suggested<br />

by the iconography <strong>of</strong> the tomb-owner’s st<strong>at</strong>ue, Davies 2008, 40, 46, pl. 2; 2010, 130, 134, fig.<br />

5; Davies and O’Connell 2009, 54, 64, fig. 9; Davies et al. 2011b, 59, 69, pl. iv, a). 2 <strong>The</strong> main<br />

focus <strong>of</strong> our epigraphic work has been HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1. It is unique in being the only pharaonic<br />

tomb yet uncovered <strong>at</strong> the site which bears its original decor<strong>at</strong>ion. Moreover, it d<strong>at</strong>es from a<br />

period, very early Dynasty 18, from which few securely d<strong>at</strong>ed tombs have survived anywhere<br />

in Egypt. <strong>The</strong> cleaning <strong>of</strong> the tomb-chapel is now finished, 3 and the recording <strong>of</strong> the<br />

decor<strong>at</strong>ion is also now complete. 4 In advance <strong>of</strong> detailed public<strong>at</strong>ion, I present here a brief<br />

<strong>overview</strong>, with selective illustr<strong>at</strong>ion, which concentr<strong>at</strong>es on some <strong>of</strong> the more interesting<br />

scenes. For previous accounts <strong>of</strong> the tomb, see Gabra 1977, 211–22; Whale 1989, 15–16, case<br />

5; Effland 1999, 26–27; Effland et al. 1999, 45–53; and, on the <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> work (carried<br />

out with the kind permission <strong>of</strong> the Permanent Committee <strong>of</strong> the SCA/MSA and with the<br />

assistance <strong>of</strong> staff <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Edfu</strong> Inspector<strong>at</strong>e), see Davies 2006, 133–34; 2008, 39–40; 2009;<br />

2010, 129–30; Davies and O’Connell 2009, 53; 2011a, 104–105; 2011b, 4; Davies et al. 2011a,<br />

36–37; 2011b, 59; Davies and O’Connell 2012, 55.<br />

<strong>The</strong> tomb-chapel <strong>of</strong> <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong><br />

Plan<br />

<strong>The</strong> plan <strong>of</strong> the superstructure (Fig. 5, left) is typical for the region and the period. <strong>The</strong> rockcut<br />

chapel, entered through a single doorway from an open courtyard (Fig. 2; cf. Davies 2009,<br />

29–30, figs 5–6), also excav<strong>at</strong>ed from the rock (and yet to be fully revealed), comprises a long<br />

rectangular chamber, oriented east-west, with a smaller rectangular niche with a raised floor<br />

<strong>at</strong> the western end (total length <strong>of</strong> chapel, approx. 10 metres). <strong>The</strong> niche (Fig. 17) once bore<br />

in its rear wall a rock-cut st<strong>at</strong>ue, probably a se<strong>at</strong>ed dyad <strong>of</strong> the tomb-owner and his wife, long<br />

disappeared. <strong>The</strong> ceiling is now badly damaged and incomplete but would originally have been<br />

<strong>of</strong> vaulted form. <strong>The</strong> burial shaft is still to be loc<strong>at</strong>ed and may lie bene<strong>at</strong>h the mound <strong>of</strong> sand<br />

and debris which covers most <strong>of</strong> the courtyard and extends to the modern monastery wall. A<br />

rectangular shaft uncovered in the south-west corner <strong>of</strong> <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>’s courtyard does not access<br />

2<br />

HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 3, though unfinished, is an impressive monument, the tomb surely <strong>of</strong> a very senior <strong>of</strong>ficial,<br />

perhaps the governor <strong>of</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> <strong>of</strong> the period. Worthy <strong>of</strong> particular note is its double doorway (Fig. 3), a rare<br />

elite fe<strong>at</strong>ure with ritual meaning, the southern door for entering, the northern for exiting (cf. Arnold 2008,<br />

18, pl. 24c; Ros<strong>at</strong>i 2010). <strong>The</strong>se functions were respected in its adapted form, as l<strong>at</strong>er motifs on the south<br />

wall almost all face inwards, while those on the north wall face outwards. <strong>The</strong> recording <strong>of</strong> the secondary<br />

decor<strong>at</strong>ion in HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 3 has been organised by Susanne Woodhouse, with hier<strong>at</strong>ic inscriptions studied by<br />

Robert Demarée.<br />

3<br />

<strong>The</strong> work <strong>of</strong> Lamia el-Hadidy, assisted throughout by Mohamed Badawy and, during various seasons, by<br />

Eric Miller and Iain Ralston.<br />

4<br />

<strong>The</strong> core epigraphic team in the <strong>Tomb</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> comprised Vivian Davies, Marcel Marée, Ilona Regulski<br />

and Claire Thorne, who has also prepared drawings for public<strong>at</strong>ion. Additional assistance has been provided<br />

by Renée Friedman, Sabine Kubisch and Will Schenck. Photographic recording has been carried out by<br />

Yarko Kobylecki and James Rossiter and planning by Günter Heindl, Focke Jarecki and Alena Schmidt.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

50 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

the substructure but ceases <strong>at</strong> a depth <strong>of</strong> about 1.5m (and may have had a symbolic function;<br />

cf. Dorman 2003, 31–32; Seyfried 2003, 61–63). <strong>The</strong> brick constructions in front <strong>of</strong> the tomb<br />

are not original. <strong>The</strong>y were probably built during the Christian re-use <strong>of</strong> the tomb, activity<br />

evidenced also in modific<strong>at</strong>ions to the interiors <strong>of</strong> both HE <strong>Tomb</strong>s 1 and 2 (see Gabra 1977,<br />

211; Davies 2006, 134; Davies and O’Connell 2009, 55–56, figs 19–20; O’Connell 2013).<br />

<strong>The</strong> tomb-owner<br />

<strong>The</strong> tomb-owner had two names. <strong>The</strong> first, his <strong>of</strong>ficial name, was written with the composite<br />

hieroglyph , probably to be read either @wt-Hr-m-wi3 or @wt-Hr-m-xb3t, ‘H<strong>at</strong>hor is in<br />

the (sacred) barque’ (Gabra 1977, 212, n. 1; Morenz 1996, 177, n. 781; Effland et al. 1999,<br />

47, n. 15). <strong>The</strong> second, his family name, was , %A-tA-im3w, ‘son <strong>of</strong> Ta-imau,’ 5<br />

normally written without the final w. <strong>The</strong>y are usually combined in the double-name formula,<br />

‘H<strong>at</strong>horemkheb<strong>at</strong> called (Ddw n.f) <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>.’ <strong>The</strong> first name (and possibly also the second)<br />

suggests an affili<strong>at</strong>ion with a cult <strong>of</strong> the goddess H<strong>at</strong>hor, which is further reflected in the<br />

tomb’s religious iconography (see further below).<br />

<strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> was a scribe and priest <strong>at</strong>tached to the temple <strong>of</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>, who served under<br />

King Ahmose, the first king <strong>of</strong> Dynasty 18, achieving career advancement with successive<br />

appointments to two significant posts in the temple, as recorded in an autobiographical text<br />

inscribed within the chapel. He died during the reign <strong>of</strong> the next king, Amenhotep I, whose<br />

names and titulary are prominently loc<strong>at</strong>ed in large hieroglyphs on the chapel’s exterior façade<br />

and on the lintel <strong>of</strong> the interior niche.<br />

<strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>’s f<strong>at</strong>her was named , ‘Geru,’ 6 and had been in royal service before him.<br />

Bearing the title , ‘chief <strong>of</strong> the ruler,’ otherwise un<strong>at</strong>tested, he may have been a military<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer. <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>’s wife, ‘mistress <strong>of</strong> the house, Ahmose,’ , was similarly well-connected.<br />

Her f<strong>at</strong>her, named , ‘Se,’ had been an <strong>of</strong>ficial (title uncertain) <strong>of</strong> a queen mother, almost<br />

certainly Queen Ahhotep, the mother <strong>of</strong> King Ahmose. 7 <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>’s mother, who had two<br />

names, one <strong>of</strong> them unclear but probably ‘Ahmose,’ the other , ‘Shere[t],’ also came from<br />

an elite background; her brother, named , ‘Djab,’ held the <strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> an administr<strong>at</strong>ive<br />

‘king’s son.’ <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> and Ahmose had a number <strong>of</strong> children, prominent among them ‘lectorpriest<br />

Amenmose,’ , shown in the tomb as the senior son.<br />

Decor<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>The</strong> tomb-chapel was hewn out <strong>of</strong> a str<strong>at</strong>um <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t sandstone which contained numerous<br />

faults and fissures. In the prepar<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the walls for the artists, these imperfections were<br />

filled in with thick white plaster to cre<strong>at</strong>e an even surface. A thin wash <strong>of</strong> plaster was then<br />

applied, which served as the ground for preliminary drafting, with prepar<strong>at</strong>ory squared grids<br />

in red used selectively. <strong>The</strong> final decor<strong>at</strong>ion was executed first in pure paint with certain<br />

scenes, in particular those depicting the primary figures, subsequently worked in sunk-relief,<br />

with raised relief used to model details within the sunk-relief figures, the relief was then<br />

5<br />

For the name Ta-imau, see Ranke 1935, 353, no. 16; Gabra 1977, 212, n. 2.<br />

6<br />

For the name, cf. Gasse and Rondot 2007, 198–99, 509 (SEH 329), 202, 515 (SHE 336).<br />

7<br />

Like the contemporary <strong>The</strong>ban <strong>of</strong>ficial Hery (see Gálan and Menéndez 2011, 147–51, with n. 23, 160, fig. 8).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

51<br />

painted. Raised relief was used to render the outline <strong>of</strong> a major figure only once, on the<br />

facade. Work on the tomb was well advanced but not completely finished. <strong>The</strong> decor<strong>at</strong>ion is<br />

now much damaged and paint, where it survives, is mostly very faded.<br />

Façade and entrance (Fig. 6)<br />

Arranged in columns, the names and titulary <strong>of</strong> Amenhotep I decor<strong>at</strong>e the jambs <strong>of</strong> the<br />

entrance, the king’s prenomen on the left (south) and nomen on the right. <strong>The</strong> lintel above the<br />

door is completely we<strong>at</strong>hered. On the façade to the right <strong>of</strong> the door is a large, unfinished,<br />

figure <strong>of</strong> a cow, sun-disk between the horns, in raised relief. Almost certainly a represent<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>of</strong> H<strong>at</strong>hor, this exterior figure is to be rel<strong>at</strong>ed to a corresponding cow-figure represented<br />

within the niche (see below). <strong>The</strong> one is shown as if entering the tomb, the other as if having<br />

emerged from the hill. Together they are probably to be understood as representing the<br />

tomb-owner’s cycle <strong>of</strong> de<strong>at</strong>h and rebirth (cf. Pinch 1993, 182–83).<br />

Also unfinished was the decor<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the reveals <strong>of</strong> the doorway, much re-used and now<br />

in poor condition. It comprises in each case the beginning <strong>of</strong> a scene representing a standing<br />

figure <strong>of</strong> the tomb-owner, loc<strong>at</strong>ed high up on the thickness facing outwards, his arms raised<br />

in ador<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the sun (Fig. 7; cf. Davies et al. 2011a, 36–37, 52, pls vi, a–b). <strong>The</strong> scene<br />

was no doubt intended, when finished, to include a figure <strong>of</strong> the wife <strong>of</strong> the tomb-owner<br />

following behind him and a hieroglyphic text comprising a solar hymn placed directly in front<br />

(cf. Assmann 1983, xiii; Dziobek 1992, 121; Kampp-Seyfried 1998, 252; Robins 2010, 136).<br />

<strong>The</strong>se are among the earliest d<strong>at</strong>ed examples <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong> scene. 8<br />

First chamber<br />

East wall (Fig. 8)<br />

<strong>The</strong> wall bears a number <strong>of</strong> hunting and fishing scenes, with the two major scenes placed<br />

apotropaically on either side <strong>of</strong> the entrance (cf. Decker and Herb 1994, 1: 431, K2.131;<br />

Davies 2009, 31–32, figs 7–8). Both have suffered substantial loss owing to the niches sunk<br />

into the walls during the l<strong>at</strong>er re-use <strong>of</strong> the tomb but still contain very interesting explan<strong>at</strong>ory<br />

texts, quite well preserved. <strong>The</strong> main scene to the south <strong>of</strong> the door shows the tombowner<br />

standing in a papyrus-bo<strong>at</strong> harpooning two fish (a Tilapia and L<strong>at</strong>es; see Brewer and<br />

Friedman 1989, 74–79), accompanied by his wife and daughter, both named Ahmose, and a<br />

son named Amenhotep. A hieroglyphic inscription describes <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> as ‘… spearing fish,<br />

enjoying himself in his plant<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> his funerary est<strong>at</strong>e in the presence <strong>of</strong> … [his] f<strong>at</strong>hers<br />

and his sons,’ a text which places the scene in the domain <strong>of</strong> the tomb-owner’s eternal afterlife<br />

accompanied by succeeding gener<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> his family (on the symbolism <strong>of</strong> such scenes in<br />

<strong>The</strong>ban tombs, see, for example, Louant 2000, 30–32; Hartwig 2004, 103–106).<br />

<strong>The</strong> equivalent scene to the north shows a hippopotamus-hunt (Fig. 9). Of the figure <strong>of</strong><br />

the tomb-owner, only the front hand survives holding a rope once shown as <strong>at</strong>tached to a<br />

harpoon now missing. Before him is a kneeling <strong>at</strong>tendant. <strong>The</strong> quarry, a large hippopotamus,<br />

with head turned backwards, is depicted in the w<strong>at</strong>er bene<strong>at</strong>h the front <strong>of</strong> the bo<strong>at</strong>, held fast<br />

8<br />

Other early Dynasty 18 examples are to be found in the tombs <strong>of</strong> Djehuty, Hormeni and Ahmose <strong>at</strong><br />

Hierakonpolis, the first two d<strong>at</strong>ed by inscription to the reign <strong>of</strong> Thutmose I (Friedman 2001, 108, 111). For<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the Djehuty scenes, see Davies 2012.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

52 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

by ropes and the butt <strong>of</strong> a harpoon. Cleaning <strong>of</strong> the scene has revealed a painted inscription<br />

in three columns reading: ‘(1) lector-priest, scribe, 9 H<strong>at</strong>horemkheb<strong>at</strong> called <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> (2)<br />

overthrowing the enemies <strong>of</strong> Horus, slaying for him (3) the rebels, so th<strong>at</strong> Horus Behdety<br />

might triumph against [his] foe.’ This is an important new text, the first to articul<strong>at</strong>e clearly<br />

the symbolic meaning <strong>of</strong> this scene in the context <strong>of</strong> a priv<strong>at</strong>e tomb: th<strong>at</strong> it represents the<br />

triumph <strong>of</strong> order over chaos, with the deceased (adopting the traditional role <strong>of</strong> the king)<br />

slaying the forces <strong>of</strong> evil, the enemies <strong>of</strong> Horus, embodied by the hippopotamus (cf. Säve-<br />

Söderbergh 1953, 25ff.; Behrmann 1996, 125ff., 164–68; Louant 2000, 32–35; Müller 2008,<br />

485). It anticip<strong>at</strong>es the theme <strong>of</strong> the ritual drama portraying the triumph <strong>of</strong> Horus known to<br />

have been enacted in the temple <strong>of</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> during the Ptolemaic period though earlier in origin<br />

(cf. Fairman 1974, 33–35), and may reflect the existence <strong>of</strong> a contemporary ritual practice. 10<br />

North and south walls<br />

<strong>The</strong> chapel’s long walls each bear major <strong>of</strong>fering-scenes associ<strong>at</strong>ed with a so-called funerary<br />

banquet, together with subsidiary scenes depicting the production and storage <strong>of</strong> food and<br />

drink (primarily me<strong>at</strong> and wine on the north and grain on the south; cf. Davies 2010, 129,<br />

134, fig. 4). <strong>The</strong> south wall also bears <strong>at</strong> its eastern end a large stela, its text destroyed. Notably<br />

absent is the standard funerary m<strong>at</strong>ter (the ‘Butic burial,’ etc) th<strong>at</strong> normally decor<strong>at</strong>es one <strong>of</strong><br />

the long walls <strong>of</strong> such tombs, as for example in the contemporary tomb <strong>of</strong> Reneny <strong>at</strong> Elkab<br />

(Tylor 1900, pls 9–13; cf. Seyfried 2003, 63, Table I). Prioritized here on both walls is the<br />

present<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the gener<strong>at</strong>ional cycle and <strong>of</strong> the family within its social and pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

context.<br />

<strong>The</strong> focal scene is th<strong>at</strong> on the north wall (Figs 10–11; cf. Davies 2009, 32–34, figs 9–10)<br />

showing the se<strong>at</strong>ed figures <strong>of</strong> tomb-owner and wife surrounded by their <strong>of</strong>fspring (with pet<br />

dog), before a pile <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>ferings. Facing them is a large figure <strong>of</strong> their senior son, Amenmose,<br />

with hands raised, reciting an <strong>of</strong>fering-formula, and behind him a series <strong>of</strong> registers showing<br />

retainers and guests <strong>at</strong> the feast, the most important among them being ‘his friend, king’s son<br />

[…], lector-priest [name lost].’ Figured centrally in the register below is a group <strong>of</strong> younger<br />

children or grandchildren (three girls and two boys), each in the charge <strong>of</strong> a nurse (cf. Davies<br />

2010, 129, 134, fig. 3).<br />

<strong>The</strong> inscription in front <strong>of</strong> the tomb-owner gives his two names and the names <strong>of</strong> his<br />

f<strong>at</strong>her and mother together with his titles: ‘lector-priest and scribe <strong>of</strong> Horus Behdety <strong>of</strong>feringpriest<br />

(Hnky) <strong>of</strong> Nebpehtyre.’ <strong>The</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter title is an abbrevi<strong>at</strong>ed version <strong>of</strong> the title ‘<strong>of</strong>feringpriest<br />

<strong>of</strong> the st<strong>at</strong>ue <strong>of</strong> millions (<strong>of</strong> years) <strong>of</strong> the person <strong>of</strong> king <strong>of</strong> Upper and Lower Egypt,<br />

Nebpehtyre,’ which is written in full in the horizontal line above (Fig. 12). According to the<br />

biographical inscription carved on the niche façade (see below, with Fig. 18), <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> was<br />

9<br />

Note the writing <strong>of</strong> sS as sSi (as occasionally also elsewhere in the tomb).<br />

10<br />

Perhaps involving the slaying <strong>of</strong> real hippopotami; see the recent discovery in <strong>Edfu</strong> <strong>of</strong> hippopotamus-bones<br />

in deposits <strong>of</strong> the Second Intermedi<strong>at</strong>e Period and New Kingdom (see Moeller 2010, 96, fig. 3; 2011, 113,<br />

fig. 3). In view <strong>of</strong> Egypt’s recent successful ‘war <strong>of</strong> liber<strong>at</strong>ion’ (in which members <strong>of</strong> <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>’s family,<br />

including his f<strong>at</strong>her, might well have been involved), the scene might have had a certain historical resonance,<br />

an example <strong>of</strong> ‘eine tradionelle königsideologische Form mit einem neuen spezifischen Sinn gefüllt …’<br />

(Morenz 2005, 180, with reference to the l<strong>at</strong>e Second Intermedi<strong>at</strong>e Period stela <strong>of</strong> Emhab from <strong>Edfu</strong>).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

53<br />

appointed to this special post by King Ahmose.<br />

<strong>An</strong> interesting subsidiary figure in the main scene, loc<strong>at</strong>ed immedi<strong>at</strong>ely behind the senior<br />

son, is th<strong>at</strong> <strong>of</strong> a military <strong>of</strong>ficer. Done entirely in paint and now incomplete, the figure is<br />

shown playing a cylindrical kemkem-drum and carrying on his back wh<strong>at</strong> appears to be a<br />

standard in the form <strong>of</strong> a stave surmounted by a Horus-head (Figs 13–14). He is identified<br />

as Tsw.f IaH-ms Dd(w) n.f *sm-Dn[d?], ‘his commander, Ahmose called Tjesem-djen[ed?]’<br />

(the second name, if the restor<strong>at</strong>ion is correct, meaning ‘mad/raging dog,’ an appropri<strong>at</strong>e<br />

nickname for a soldier; cf. Vernus 1986, 126, f, on ‘noms d’animaux’ as applied to humans;<br />

also Lopes 1998, 710). <strong>The</strong> scene <strong>of</strong> which he was part is otherwise lost but may, when<br />

complete, have shown a group <strong>of</strong> musicians (cf. for example, Manniche 1991, 54–56, fig.<br />

31), perhaps in this case a military band (for recent discussion <strong>of</strong> the cylinder-drum, see<br />

Klotz 2010, 231–33, with reference to the military context <strong>of</strong> the kemkem-drum fe<strong>at</strong>ured<br />

in the stela <strong>of</strong> Emhab from <strong>Edfu</strong>). <strong>The</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficer’s associ<strong>at</strong>ion with the tomb-owner (‘his<br />

commander’) suggests the possibility th<strong>at</strong> the l<strong>at</strong>ter’s duties had <strong>at</strong> some time during his<br />

career included a military role (perhaps following th<strong>at</strong> <strong>of</strong> his f<strong>at</strong>her).<br />

Scenes <strong>of</strong> the family, now badly damaged, domin<strong>at</strong>e the south wall (Figs 15–16; cf. Davies<br />

2006, 134, 145, pl. iii). On the right, the tomb-owner stands before his se<strong>at</strong>ed parents, making<br />

<strong>of</strong>ferings ‘[for the ka <strong>of</strong>] my f<strong>at</strong>her and my mother.’ (cf. Seyfried 1995, 223–31). Interestingly,<br />

the mother is shown with light red skin distinguishing her from the other female figures in<br />

the tomb, which are coloured the conventional yellow, 11 possibly here signalling her elev<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

ancestral st<strong>at</strong>us (cf. Seyfried 1995, 229–31). 12 In the central <strong>of</strong>fering-scene, two <strong>of</strong> the three<br />

surviving figures, both named Ahmose, are identified as ‘his brother.’ Other ‘brothers’ and<br />

‘sisters’ are figured among the se<strong>at</strong>ed and squ<strong>at</strong>ting guests, which also include ‘his nurse,<br />

Henut’ (cf. Davies 2006, 134, 139, fig. 3). On the left, <strong>at</strong> the bottom <strong>of</strong> the stela (Fig. 16), the<br />

tomb-owner and wife receive <strong>of</strong>ferings from their children (seven sons and three daughters,<br />

some <strong>of</strong> them perhaps grandchildren), led again by the senior son, Amenmose.<br />

On a technical point, the central scenes <strong>of</strong> both walls were initially drafted with the aid <strong>of</strong><br />

squared grids, remnants <strong>of</strong> which survive, most visibly on the south wall. From these it can<br />

be estim<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> the major se<strong>at</strong>ed figures occupied fourteen squares from the bottom <strong>of</strong> the<br />

feet to the hairline, as is usual for the period (see Robins 2001, 60).<br />

Niche, façade (Fig. 17)<br />

<strong>The</strong> niche façade is decor<strong>at</strong>ed with three sets <strong>of</strong> inscription (all deliber<strong>at</strong>ely damaged,<br />

but still legible): one on the lintel, comprising two horizontal lines, and one each on the left<br />

and right jambs respectively, arranged in four columns (cf. Davies 2006, 133, 143–44, pls<br />

1–2; Davies 2009, 33–36, figs 11–12). <strong>The</strong> upper line on the lintel contains a winged sundisc<br />

in the centre and on either side the epithets <strong>of</strong> Horus Behdety. <strong>The</strong> lower contains a<br />

central ankh-sign flanked to right and left by the titulary and prenomen and nomen respectively<br />

11<br />

All except for the figure <strong>of</strong> a Nubian servant in a subsidiary scene on the north wall, which is coloured<br />

black.<br />

12<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> skin-colour in the tomb, red is otherwise used not only for male figures but also for the gods<br />

(Horus on the south wall <strong>of</strong> the niche, Shu on the north; see below).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

54 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

<strong>of</strong> Amenhotep I together with dedic<strong>at</strong>ions to Horus Behdety and Isis. <strong>The</strong> inscription on<br />

the right jamb, now incomplete, is an address to the living, ending with the tomb-owner’s<br />

genealogy: ‘(4) … <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>, engendered by the chief <strong>of</strong> the ruler, Geru, and born to the<br />

sister <strong>of</strong> the king’s son <strong>of</strong> the district <strong>of</strong> the south[erner]s (?), Djab, [mother’s name lost].’ <strong>The</strong><br />

inscription on the left jamb is a biographical text (Fig. 18):<br />

‘(1) Favours from the king concerning the temple <strong>of</strong> Horus Behdety. (My) Lord gave<br />

to (me) a favour: his causing th<strong>at</strong> I be appointed to be second lector-priest <strong>of</strong> Horus<br />

[Behde]ty. (2) (My) Lord repe<strong>at</strong>ed for me a favour: [he] enjoined to (me) his st<strong>at</strong>ue 13<br />

which is in its hall, which is in this temple, its income having been fixed, (it) being settled<br />

and enduring. 14 (3) Bread, 180 portions; beer, 6 jars; pure me<strong>at</strong>, flesh; haunch; back;<br />

spine; kidney f<strong>at</strong>; kheru-fields; 10(?) hectares; kayt-fields, 30 hectares—preserved as an<br />

eternal [ordin]ance 15 (4) and as a permanent record in a decree <strong>of</strong> king Nebpehtyre,<br />

justified, strong ruler who seized the two lands, in the house <strong>of</strong> his f<strong>at</strong>her, Horus<br />

Behdety, the gre<strong>at</strong> god.’<br />

This text, one <strong>of</strong> the earliest ‘autobiographies’ <strong>of</strong> Dynasty 18, records th<strong>at</strong> King Ahmose<br />

twice favoured the tomb-owner with pr<strong>of</strong>essional advancement. <strong>The</strong> king first appointed<br />

him to be second lector-priest in the temple <strong>of</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>. <strong>The</strong> title <strong>of</strong> ‘second lector-priest’<br />

is inform<strong>at</strong>ive, suggesting the existence <strong>of</strong> a rel<strong>at</strong>ively developed priestly hierarchy, with<br />

accompanying infrastructure, in the temple <strong>of</strong> the period (cf. Morenz 1996, 177–78). <strong>The</strong><br />

king next appointed him to be the <strong>of</strong>fering-priest <strong>of</strong> a st<strong>at</strong>ue <strong>of</strong> the king loc<strong>at</strong>ed in its own<br />

hall in the temple. This is the st<strong>at</strong>ue named in the north wall frieze-inscription as the ‘st<strong>at</strong>ue<br />

<strong>of</strong> millions (<strong>of</strong> years) 16 <strong>of</strong> the person <strong>of</strong> king <strong>of</strong> Upper and Lower Egypt, Nebpehtyre,’ <strong>of</strong><br />

which the tomb owner is the henky (Hnky), the title conferred on a priest enjoined to such<br />

a st<strong>at</strong>ue-cult (cf. Helck 1961, 226–28; Gabra 1977, 215–17; Graefe 1981, ii, 52–53; Helck<br />

1986, 1266; Effland et al. 1999, 52). <strong>The</strong> hieroglyph which determines the word for st<strong>at</strong>ue<br />

(tw[t]) in column 2 shows a figure <strong>of</strong> the king wearing a short wig with uraeus <strong>at</strong> the front,<br />

se<strong>at</strong>ed on a throne holding a stave in his left hand and a cloth in his right. This is not the<br />

generic determin<strong>at</strong>ive <strong>of</strong> the word, Gardiner A53, which is present in the frieze-inscription<br />

example (Fig. 12) and may possibly point to the form <strong>of</strong> the actual st<strong>at</strong>ue. This st<strong>at</strong>ue was<br />

endowed in perpetuity with design<strong>at</strong>ed quantities <strong>of</strong> food and drink and with land to sustain<br />

the cult by authority <strong>of</strong> a royal decree recorded and preserved in the temple <strong>of</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>, the<br />

essential content <strong>of</strong> which the tomb-text probably reproduces in main part. A similar, nearcontemporary<br />

set <strong>of</strong> endowments also <strong>at</strong>tached to royal st<strong>at</strong>ues <strong>at</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> is documented in<br />

the stela <strong>of</strong> Iuf (Cairo CG 34009; Urk. iv, 29–31; Helck 1961, 226, no. 1; Gabra 1977, 217;<br />

13<br />

Reading: mni. n.[f] n.(i) tw[t].f. For mni in this sense, cf. Urk. iv, 30, 15; 31, 10 (stela <strong>of</strong> Iuf from <strong>Edfu</strong>); and<br />

2109, 13; Helck 1961, 226; Derchain 1985, 9.<br />

14<br />

Reading the last group as r(w)[d], which is confirmed by the determin<strong>at</strong>ive.<br />

15<br />

Reading m wD (<strong>of</strong> which there are clear traces) <strong>at</strong> the bottom <strong>of</strong> column 3.<br />

16<br />

In full, hH m rnpwt; cf. Urk. iv, 1495, 4; Gabolde 1991, 167–68; Frood 2003, 70–71 (d), pl. 5, line 11; Bryan<br />

2006, 112; Delvaux 2010, 70.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

55<br />

Gabolde 1991, 170; Frood 2003, 70–71 (e); Barbotin 2008, 50, 230–31, doc. 24; Delvaux<br />

2010, 69ff.).<br />

This short text contains much interesting inform<strong>at</strong>ion, bearing not only on the tombowner’s<br />

career progression but also on the institutions, architecture and content <strong>of</strong> the<br />

very early Dynasty 18 temple <strong>of</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>, the p<strong>at</strong>ronage <strong>of</strong> the king confirming the political<br />

importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> to the new <strong>The</strong>ban dynasty (cf. Vandersleyen 1995, 201–202, with n. 1;<br />

Morenz 1996, 178, 180–81; Barbotin 2008, 50), a st<strong>at</strong>e <strong>of</strong> affairs to which the stela <strong>of</strong> Iuf<br />

also bears witness.<br />

Niche, interior<br />

As already noted above, the niche once contained in its rear wall rock-cut figures, probably<br />

a se<strong>at</strong>ed pair representing the tomb-owner and his wife, <strong>of</strong> which only remnants <strong>of</strong> the se<strong>at</strong><br />

survive. <strong>The</strong> side walls are also very badly damaged, especially the south wall, but they still<br />

bear substantial remains <strong>of</strong> the original scenes.<br />

South wall <strong>of</strong> niche<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are two scenes on the south wall (Fig. 19). <strong>The</strong> one on the right, nearest to the<br />

st<strong>at</strong>ues, depicts an <strong>of</strong>fering-list and, bene<strong>at</strong>h, a series <strong>of</strong> male figures carrying out an opening<strong>of</strong>-the-mouth<br />

ritual (cf. Davies and O’Connell 2009, 53, 63, fig. 7; Davies et al. 2011b, 59, 68,<br />

pl. iii, a). <strong>The</strong> larger, main scene on the left (Fig. 20; cf. Davies 2009, 35–37, fig. 13; Davies<br />

et al. 2011a, 37, 53, pl. vii) shows the tomb-owner in an act <strong>of</strong> so-called ‘personal piety’<br />

(cf. Baines 2009, 12), kneeling and <strong>of</strong>fering to three <strong>Edfu</strong> deities, identified respectively as<br />

‘Horus Behdety, gre<strong>at</strong> god, lord <strong>of</strong> heaven,’ ‘H<strong>at</strong>hor who dwells in Behdet, mistress <strong>of</strong> this<br />

perfect mound,’ and ‘Heded(et), mistress <strong>of</strong> […],’ the l<strong>at</strong>ter a scorpion-goddess and local<br />

manifest<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Isis. 17 Horus was shown se<strong>at</strong>ed holding a wAs-sceptre, with the goddesses<br />

standing behind him. <strong>The</strong> figures, possibly to be understood as representing st<strong>at</strong>ues, are<br />

mostly lost but a section <strong>of</strong> Horus’s front foot coloured red (placed on a dais or pedestal), and<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> their headgear survive, a double crown for Horus, sun-disc and horns for H<strong>at</strong>hor,<br />

and a modius supporting an enormous scorpion for Heded(et). 18 Noteworthy is H<strong>at</strong>hor’s<br />

second epithet, nbt iAt tn nfr(t), ‘mistress <strong>of</strong> this perfect mound,’ since it identifies <strong>Hagr</strong><br />

<strong>Edfu</strong> as a sacred mound (<strong>of</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ion), possibly Behdet itself, and H<strong>at</strong>hor as having a special<br />

proprietorial interest in the site (cf. Gabra 1977, 219–20, fig. 7, bottom, 221; Kurth 1994, 95,<br />

n. 13; Morenz 1996, 177–78, n. 784; Effland 1999, 27; on votive ‘H<strong>at</strong>hor-jars’ found <strong>at</strong> the<br />

site, see Davies and O’Connell 2012, 56, 85, fig. 39). <strong>The</strong> whole scene is contained within a<br />

frame comprising the hieroglyph for sky <strong>at</strong> the top supported by two tall wAs-sceptres <strong>at</strong> the<br />

sides, which demarc<strong>at</strong>es the sacred space occupied by the gods. <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>’s figure is included<br />

within this space.<br />

17<br />

For Hededet, see Wessetzky 1993; Leitz 2002, 597–98; Bryan 2002. This <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> image, albeit vestigial, is<br />

now the earliest securely d<strong>at</strong>ed represent<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> this deity.<br />

18<br />

For a figure <strong>of</strong> Isis with scorpion on head in a similar scene from the near-by site <strong>of</strong> Hierakonpolis, see<br />

Friedman 2001, 111, colour pl<strong>at</strong>e 37.3 (st<strong>at</strong>ue-niche, tomb <strong>of</strong> Hormeni, temp. Thutmose I).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

56 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

North wall <strong>of</strong> niche<br />

<strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>’s privileged tre<strong>at</strong>ment and H<strong>at</strong>hor’s special funerary role are both confirmed<br />

by a unique scene on the north wall (Figs 21–22; cf. Effland et al. 1999, 53; Davies 2008,<br />

40, 43, fig. 2, 45, pl. 1; Davies 2009, 35–38, fig. 14; Davies et al. 2011a, 37, 54, pl. viii, a). It<br />

shows three registers <strong>of</strong> female <strong>of</strong>fering-bearers (the topmost done in paint only, now very<br />

faded), among them the tomb-owner’s wife and daughters, identified in turn as ‘his wife,’ ‘his<br />

daughter,’ etc, <strong>of</strong>fering to a dominant central image, th<strong>at</strong> <strong>of</strong> a large cow (already mentioned<br />

above in connection with the cow-figure on the façade, Fig. 6) standing within, and emerging<br />

from, a shrine on a sacred barque, the cow supported centrally by the arms (the left arm<br />

now lost) <strong>of</strong> a smaller kneeling divine figure, his body coloured red. <strong>The</strong> barque rests on a<br />

narrow, rectangular support. <strong>The</strong> front <strong>of</strong> the cow and barque are lost in the crack in the wall<br />

(an estim<strong>at</strong>e <strong>of</strong> the available space suggesting there was little or no room for other elements<br />

<strong>of</strong> decor<strong>at</strong>ion like a standing figure to have once been included here). <strong>The</strong> cow in this case<br />

represents a composite deity. She is H<strong>at</strong>hor in the barque, emerged from the perfect mound.<br />

She is also the sky-goddess, the celestial cow, here probably an aspect <strong>of</strong> Isis, raised up and<br />

supported by the god Shu (or a heh-god). This duality is confirmed by the text above the<br />

cow’s head (Fig. 23), which labels the figure as ‘[Isis?] beloved <strong>of</strong> Horus (and) H<strong>at</strong>hor […]<br />

head <strong>of</strong> the (holy) cows.’ <strong>The</strong> icon combines two modes <strong>of</strong> rebirth, terrestrial and solar,<br />

for the tomb-owner, his identity, I would suggest, embodied in the image, which functions<br />

on one level as a large hieroglyph writing his name, ‘H<strong>at</strong>hor is in the barque.’ 19 He is thus<br />

presented as being one with the deity, an audacious conceit, though clearly ‘authorised,’ as<br />

is the unusual <strong>of</strong>fering-scene on the opposite wall, by the presence <strong>of</strong> the king’s names and<br />

titulary, prominently displayed, on the lintel <strong>of</strong> the niche. 20<br />

<strong>The</strong> depiction <strong>of</strong> the H<strong>at</strong>hor-cow in her barque in the H<strong>at</strong>hor-shrine <strong>of</strong> H<strong>at</strong>shepsut<br />

<strong>at</strong> Deir el-Bahri (see Naville [1901], 5, pl. 104; Blumenthal 2001, 35–36, fig. 23) has been<br />

regarded as the earliest example <strong>of</strong> such an image (for example, Müller 2003, 61, 68, 116),<br />

while the represent<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the celestial cow is otherwise first <strong>at</strong>tested in <strong>The</strong>ban royal tombiconography<br />

<strong>of</strong> l<strong>at</strong>e Dynasty 18 (see Hornung 1982, 81–85, fig. 3; Effland et al. 1999, 53;<br />

Guihou 2010). <strong>The</strong> appearance <strong>of</strong> the two motifs, imagin<strong>at</strong>ively combined, in a priv<strong>at</strong>e tomb<br />

<strong>of</strong> early Dynasty 18 in <strong>Edfu</strong> indic<strong>at</strong>es an earlier origin for both and a wider, less restricted<br />

sphere <strong>of</strong> use and deployment. 21 It is unlikely th<strong>at</strong> they were first cre<strong>at</strong>ed for <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong>. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

19<br />

A two-dimensional precursor <strong>of</strong> the famous rebus-sculpture, <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> EA 43, reading Mwt-m-wiA,<br />

‘Mut is in the barque’ (see Fischer 1972, 21–22; Quirke and Spencer 1992, 77–78, no. 56; Bryan 1992, 126,<br />

fig. 5.4; Müller 2003, 87; Morenz 2008, 187; Karlshausen 2009, 50–51).<br />

20<br />

Cf. the unusual scenes in Silsilah chapel no. 21 <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>ficial Menkh, temp. Tuthmose I (Caminos and<br />

James 1963, 70–71, pl. 54, left and right upper register; Spieser 2000, 240–41 and 333, no. 173), with human<br />

figures, probably the chapel-owner, <strong>of</strong>fering directly to the gods Haroeris and Sobek (here shown standing<br />

on the base-line), who in turn give life to the king represented by his name, which is positioned directly<br />

above the scenes; also Kucharek 2010, 148–56, on the decor<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the l<strong>at</strong>er chapel <strong>of</strong> Senenmut (Silsilah<br />

no. 16) with its unique temple-like content, an example <strong>of</strong> ‘Die Verquickung von Elementen priv<strong>at</strong>er und<br />

königlicher Kultsphären … nur im Rahmen ausserordentlicher königlicher Gunst möglich.’<br />

21<br />

Indic<strong>at</strong>ive <strong>of</strong> a developing momentum in the elite appropri<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> royal/divine iconographic forms<br />

anticip<strong>at</strong>ed in the earlier <strong>Edfu</strong> stela <strong>of</strong> Emhab (see Baines 1986, 50–53; Morenz 2005, 177–80; Kubisch<br />

2008, 238–39; Klotz 2010, 214–17).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

57<br />

were surely adapted by the tomb-owner and his designers from current temple-models,<br />

elements perhaps in a now-lost decor<strong>at</strong>ive programme <strong>of</strong> Amenhotep I in the temple <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Edfu</strong> (like th<strong>at</strong> <strong>at</strong>tested <strong>at</strong> near-by Elkab; see Werbrouck 1940–54, especially pl. 44A; Schmitz<br />

1978, 5, 121–23; Pinch 1993, 175) or in a temple or H<strong>at</strong>hor-shrine <strong>at</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> (yet to be<br />

loc<strong>at</strong>ed; see Sauneron 1958, 278–79, n. 3; Effland 1999, 30; Gabra 1977, 221–22; Gabra 1984,<br />

7; Egberts 1998, 799–800, with n. 49), the st<strong>at</strong>ion, it might be surmised, for a processional<br />

cult-st<strong>at</strong>ue <strong>of</strong> ‘H<strong>at</strong>hor is in the barque’ resembling in form the image depicted in the nichescene<br />

and celebr<strong>at</strong>ed in the <strong>of</strong>ficial name <strong>of</strong> the tomb-owner. 22<br />

Conclusion<br />

<strong>The</strong> tomb-chapel <strong>of</strong> <strong>S<strong>at</strong>aimau</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> (HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1) is rich in d<strong>at</strong>a on a range <strong>of</strong><br />

interrel<strong>at</strong>ed subjects <strong>of</strong> both regional and more general import: on political and personal<br />

p<strong>at</strong>ronage, career advancement and temple institutions; on expressions <strong>of</strong> local identity and<br />

social st<strong>at</strong>us; on religious iconography and the priv<strong>at</strong>e elite assumption <strong>of</strong> royal prerog<strong>at</strong>ives;<br />

on tomb and site as parts <strong>of</strong> a wider sacred landscape; on the n<strong>at</strong>ure <strong>of</strong> l<strong>at</strong>er re-use. To wh<strong>at</strong><br />

extent the tomb’s decor<strong>at</strong>ive programme, with its seemingly unusual elements, is represent<strong>at</strong>ive<br />

<strong>of</strong> the prevailing repertoire, it is impossible to say, as it presently stands alone. <strong>The</strong>re can<br />

be little doubt, however, th<strong>at</strong> contemporary monuments, still to be uncovered, are loc<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

elsewhere in <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>, probably in the vicinity <strong>of</strong> HE <strong>Tomb</strong>s 1–3. <strong>The</strong> area immedi<strong>at</strong>ely to<br />

the south <strong>of</strong> the group along the same terrace (Fig. 4), <strong>of</strong> which nothing is currently known,<br />

has obvious potential and could be a productive focus for future work on this enormously<br />

promising site.<br />

Frontispiece: <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> from the north, with the modern monastery <strong>at</strong> the foot <strong>of</strong> the main hill (Photo:<br />

W. V. Davies).<br />

Bibliography<br />

Alliot, M. 1954. Le culte d’Horus à Edfou au temps des Ptolémées. BdE 20. Cairo.<br />

Arnold, D. 2008. Middle Kingdom tomb architecture <strong>at</strong> Lisht. Public<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> the Metropolitan<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art Egyptian Expedition 28. New York.<br />

Assmann, J. 1983. Sonnenhymnen in <strong>The</strong>banischen Gräbern. <strong>The</strong>ben I. Mainz am Rhein.<br />

Baines, J. 1986. <strong>The</strong> stela <strong>of</strong> Emhab: Innov<strong>at</strong>ion, tradition, hierarchy. JEA 72: 41–53.<br />

———. 2009. <strong>The</strong> stelae <strong>of</strong> Amenisonbe from Abydos and Middle Kingdom display <strong>of</strong><br />

personal religion. In Sitting beside Lepsius: Studies in honour <strong>of</strong> Jaromir Malek <strong>at</strong> the Griffith<br />

22<br />

Note th<strong>at</strong> cult-images depicting the cow-in-the-barque are among the motifs carved on the walls <strong>of</strong> the<br />

neighbouring tomb-turned-temple (HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 3). For a substantial, l<strong>at</strong>er structure <strong>at</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>, sunk deep<br />

into the rock and fronted by a pylon, th<strong>at</strong> might have functioned as a barque-shrine for one or more <strong>of</strong> the<br />

local (and possibly visiting) gods, see Davies 2010, 130–31, 136, figs 7–8, 139, fig. 13; O’Connell 2010, 4–7,<br />

figs 5–8; Davies and O’Connell 2011a, 105, 126–27, figs 27–29, referred to as ‘pylon-tomb.’<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

58 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Institute, D. Magee, J. Bourriau and S. Quirke (eds), 1–22. OLA 185. Leuven; Paris; Walpole.<br />

Barbotin, C. 2008. Âhmosis et la début de la XVIIIe dynastie. Paris.<br />

Behrmann, A. 1996. Das Nilpferd in der Vorstellungswelt der Alten Ägypter II: Textband. Frankfurt<br />

am Main; Berlin; Bern; New York; Paris; Wien.<br />

Blumenthal, E. 2001. Kuhgöttin und Gottkönig: Frömmigkeit und Sta<strong>at</strong>streue auf der Stele Leipzig<br />

Ägyptisches <strong>Museum</strong> 5141. Leipzig.<br />

Brewer, D. J. and R. F. Friedman 1989. Fish and fishing in ancient Egypt. Warminster.<br />

Bryan, B. M. 1992. Royal and divine st<strong>at</strong>uary. In Egypt’s dazzling sun: Amenhotep III and his world,<br />

A. P. Kozl<strong>of</strong>f, B. M. Bryan and L. M. Berman (eds), 125–53. Cleveland, OH.<br />

———. 2002. Scorpion stone. In <strong>The</strong> quest for immortality: Treasures <strong>of</strong> ancient Egypt, E. Hornung<br />

and B. M. Bryan (eds), 183, no. 90. Washington, DC.<br />

———. 2006. Administr<strong>at</strong>ion in the reign <strong>of</strong> Thutmose III. In Thutmose III: A new biography,<br />

E. H. Cline and D. O’Connor (eds), 69–122. <strong>An</strong>n Arbor, MI.<br />

Bunbury, J. M., A. Graham and K. D. Strutt. 2009. Kom el-Farahy: A New Kingdom island in<br />

an evolving <strong>Edfu</strong> floodplain. BMSAES 14: 1–23.<br />

Caminos, R. A. and T. G. H. James. 1963. Gebel Es-Silsilah I: <strong>The</strong> shrines. ASE 31. London.<br />

Davies, W. V. 2006. <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Epigraphic Expedition report on the 2005 season. ASAE<br />

80: 133–51.<br />

———. 2008. <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Epigraphic Expedition report on the 2006 season. ASAE 82:<br />

39–48.<br />

———. 2009. La tombe de S<strong>at</strong>aimaou à Hagar Edfou. Égypte, Afrique & Orient 53: 25–40.<br />

———. 2010. <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Epigraphic Expedition report on the 2007 season. ASAE 84:<br />

129–41.<br />

———. 2012. Sun-worship <strong>at</strong> Hierakonpolis: Insights from Edinburgh. Nekhen News 24: 27.<br />

Davies, W. V. and E. R. O’Connell. 2009. <strong>The</strong> <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Expedition to Elkab and <strong>Hagr</strong><br />

<strong>Edfu</strong>, 2009. BMSAES 14: 51–72.<br />

———. 2011a. <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Expedition to Elkab and <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>, 2010. BMSAES 16:<br />

101–32.<br />

———. 2011b. <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Expedition to Elkab and <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>, 2011. BMSAES 17:<br />

1–29.<br />

———. 2012. <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Expedition to Elkab and <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>, 2012. BMSAES 19:<br />

51–85.<br />

Davies, W. V. et al. 2011a. <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Expedition report on the 2008 season. ASAE 85:<br />

33–55.<br />

———. 2011b. <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Expedition 2009. ASAE 85: 57–73.<br />

Decker, W. and M. Herb (eds). 1994. Bild<strong>at</strong>las zum Sport im Alten Ägypten: Corpus der bildlichen<br />

Quellen zu Leibesübungen, Spiel, Jagd, Tanz und verwandten <strong>The</strong>men. 2 vols. Leiden; New York;<br />

Köln.<br />

Delvaux, L. 2010. La st<strong>at</strong>ue de Thoutmosis Ier <strong>of</strong>ferte à Qenamon (TT 93). In Thèbes aux 101<br />

portes: Mélanges à la mémoire de Roland Tefnin, E. Warmenbol and V. <strong>An</strong>genot (eds), 63–77.<br />

MA 12. Turnhout.<br />

Derchain, P. 1985. Sinouhé et Ammounech. GM 87: 7–13.<br />

Dorman, P. F. 2003. Family burial and commemor<strong>at</strong>ion in the <strong>The</strong>ban Necropolis. In <strong>The</strong><br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

59<br />

<strong>The</strong>ban Necropolis: Past, present and future, N. Strudwick and J. H. Taylor (eds), 30–41. London.<br />

Dziobek, E. 1992. Das Grab des Ineni, <strong>The</strong>ben Nr. 81. AV 68. Mainz am Rhein.<br />

Effland, A. 1999. Zur Grabungsgeschichte der archäologischen Stätten zwischen Hager <strong>Edfu</strong><br />

und Nag‘ El-Hisaja Al-Gharbi. In <strong>Edfu</strong>: Bericht über drei Surveys. M<strong>at</strong>erialien und Studien, D.<br />

Kurth (ed.), 21–39. Die Inschriften des Tempels von <strong>Edfu</strong> Beihheft 5. Wiesbaden.<br />

Effland, A., D. Kurth, E. Pardey and W. Waitkus. 1999. Bericht über drei Surveys im Gebiet<br />

zwischen Hager <strong>Edfu</strong> und Nag‘ El-Hisaja. In <strong>Edfu</strong>: Bericht über drei Surveys. M<strong>at</strong>erialien<br />

und Studien, D. Kurth (ed.), 40–68. Die Inschriften des Tempels von <strong>Edfu</strong> Beihheft 5.<br />

Wiesbaden.<br />

Effland, A. and J. P. Graeff. 2010. Nochmals zur Lage von Behedet. In <strong>Edfu</strong>: M<strong>at</strong>erialien und<br />

Studien, D. Kurth and W. Waitkus (eds), 25–39. Die Inschriften des Tempels von <strong>Edfu</strong><br />

Beihheft 6. Gladbeck.<br />

Egberts, A. 1995. Praxis und System: Die Beziehungen zwischen Liturgie und Tempeldekor<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

am Beispiel des Festes von Behedet. In Systeme und Programme der ägyptischen Tempeldekor<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

3. Ägyptologische Tempeltagung, Hamburg, 1.–5. Juni 1994, D. Kurth, W. Waitkus and S.<br />

Woodhouse (eds), 13–38. AÜAT 33.1. Wiesbaden.<br />

———. 1998. <strong>The</strong> pylons <strong>of</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>. In Egyptian religion: <strong>The</strong> last thousand years. Studies dedic<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

to the memory <strong>of</strong> Jan Quaegebeur, W. Clarysse, A. Schoors and H. Willems (eds), 2: 789–801.<br />

OLA 85. Leuven.<br />

Fairman, H. W. 1974. <strong>The</strong> triumph <strong>of</strong> Horus: <strong>An</strong> ancient Egyptian sacred drama. London.<br />

Fakhry, A. 1947. A report on the inspector<strong>at</strong>e <strong>of</strong> Upper Egypt. ASAE 46: 25–54.<br />

Fischer, H. G. 1972. Some emblem<strong>at</strong>ic uses <strong>of</strong> hieroglyphs with particular reference to an<br />

archaic ritual vessel. MMJ 5: 5–23.<br />

Frood, E. 2003. Ritual function and priestly narr<strong>at</strong>ive: <strong>The</strong> stelae <strong>of</strong> the High Priest <strong>of</strong> Osiris,<br />

Nebwawy. JEA 89: 59–81.<br />

Friedman, R. 2001. <strong>The</strong> dynastic tombs <strong>at</strong> Hierakonpolis: Painted tombs <strong>of</strong> the early<br />

Eighteenth Dynasty. In Colour and painting in ancient Egypt, W. V. Davies (ed.), 106–112.<br />

London.<br />

Gabolde, L. 1991. Un fragment de stele au nom d’Ahmes-Nefertary provenant de Karnak.<br />

BIFAO 91: 161–71.<br />

Gabra, G. 1977. <strong>The</strong> site <strong>of</strong> Hager <strong>Edfu</strong> as the New Kingdom cemetery <strong>of</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>. CdÉ 52:<br />

207–22.<br />

———. 1984. Zwei Stelenfragmente aus <strong>Edfu</strong>. GM 75: 7–11.<br />

Galán, J. M. and G. Menéndez. 2011. <strong>The</strong> funerary banquet <strong>of</strong> Hery (TT 12), robbed and<br />

restored. JEA 97: 143–66.<br />

Gasse, A. and V. Rondot. 2007. Les inscriptions de Séhel. MIFAO 126. Cairo.<br />

Graefe, E. 1981. Untersuchungen zur Verwaltung und Geschichte der Institution der Gottesgemahlin des<br />

Amun vom Beginn des Neuen Reiches bis zur Spätzeit. 2 vols. ÄA 37. Wiesbaden.<br />

Guihou, N. 2010. Myth <strong>of</strong> the heavenly cow. In UCLA Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Egyptology,<br />

J. Dieleman and W. Wendrich (eds). Los <strong>An</strong>geles. http://www.escholarship.org/uc/<br />

item/2vh551hn (last accessed May 2013).<br />

Hartwig, M. 2004. <strong>Tomb</strong> painting and identity in ancient <strong>The</strong>bes, 1419–1372 BCE. Monumenta<br />

Aegyptiaca 10. Turnhout.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

60 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Helck, W. 1961. M<strong>at</strong>erialien zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte des Neuen Reiches II. Wiesbaden.<br />

———. 1986. St<strong>at</strong>uenkult. LÄ 5: 1265–67. Wiesbaden.<br />

Hornung, E. 1982. Der Ägyptische Mythos von der Himmelskuh: Eine Ätiologie des Unvollkommenen.<br />

OBO 46. Freiburg; Göttingen.<br />

Kampp-Seyfried, F. 1998. Overcoming de<strong>at</strong>h: <strong>The</strong> priv<strong>at</strong>e tombs <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong>bes. In Egypt: <strong>The</strong><br />

world <strong>of</strong> the pharaohs, R. Schulz and M. Seidel (eds), 249–63. Köln.<br />

Karlshausen, C. 2009. L’iconographie de la barque processionnelle divine en Égypte au Nouvel Empire.<br />

OLA 182. Leuven; Paris; Walpole.<br />

Klotz, D. 2010. Emhab versus the tmrhtn: Monomachy and the expulsion <strong>of</strong> the Hyksos.<br />

SAK 39: 211–41.<br />

Kubisch, S. 2008. Lebensbilder der 2. Zwischenzeit: Biographische Inschriften der 13.–17 Dynastie.<br />

SDAIK 34. Berlin; New York.<br />

Kucharek, A. 2010. Senenmut in Gebel es-Silsilah. MDAIK 66: 143–59.<br />

Kurth, D. 1994. Zur Lage von Behedet, dem Heiligen Bezirk von <strong>Edfu</strong>. GM 142: 93–100.<br />

Kurth, D. 1999. <strong>Edfu</strong>. In Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> the archaeology <strong>of</strong> ancient Egypt, K. Bard (ed.), 269–71.<br />

London; New York.<br />

Leitz, C. (ed.). 2002. Lexikon der Ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen 5. OLA 114. Leuven;<br />

Paris; Dudley.<br />

Lopes, M. H. T. 1998. Les noms propres au Nouvel Empire. In Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Seventh<br />

Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Congress <strong>of</strong> Egyptologists, Cambridge, 3–9 September 1995, C. J. Eyre (ed.), 703–711.<br />

OLA 82. Leuven.<br />

Louant, E. 2000. Comment Pouiemrê triompha de la mort: <strong>An</strong>alyse du programme iconographique de la<br />

tombe thébaine no. 39. Lettres Orientales 6. Leuven.<br />

Manniche, L. 1991. Music and musicians in ancient Egypt. London.<br />

Moeller, N. 2010. Tell <strong>Edfu</strong>. <strong>The</strong> Oriental Institute <strong>An</strong>nual Report 2009–2010: 94–104.<br />

———. 2011. Tell <strong>Edfu</strong>. <strong>The</strong> Oriental Institute <strong>An</strong>nual Report 2010–2011: 112–21.<br />

Morenz, L. D. 1996. Beiträge zur Schriftlichkeitskultur im Mittleren Reich und in der 2. Zwischenzeit.<br />

ÄAT 29. Wiesbaden.<br />

———. 2005. Em-habs Feldzugsbericht: Bild-textliche Inszenierung von ‘Grosser Geschichte’<br />

im Spiegel der Elite. A & L 15: 169–80.<br />

———. 2008. Sinn und Spiel der Zeichen: Visuelle Poesie im Alten Ägypten. Pictura et Poesis 21.<br />

Köln; Weimar; Wien.<br />

Müller, M. 2003. Die Göttin im Boot: Eine ikonographische Untersuchung. In Menschenbilder-<br />

Bildermenschen: Kunst und Kultur im Alten Ägypten, T. H<strong>of</strong>mann and A. Sturm (eds), 57–126.<br />

Norderstedt.<br />

Müller, V. 2008. Nilpferdjagd und geköpfte Feinde: Zu zwei Ikonen des Feindvernichtungsrituals.<br />

In Zeichen aus dem Sand: Streiflichter aus Ägyptens Geschichte zu Ehren von Günter Dreyer, E.-M.<br />

Engel, V. Müller and U. Hartung (eds), 477–93. Menes 5. Wiesbaden.<br />

Naville, E. [1901]. <strong>The</strong> temple <strong>of</strong> Deir El Bahari IV: <strong>The</strong> shrine <strong>of</strong> H<strong>at</strong>hor and the southern hall <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>ferings. London.<br />

O’Connell, E. R. 2010. <strong>The</strong> <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Expedition to <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> 2010: Conserv<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

through Document<strong>at</strong>ion Project. Bulletin <strong>of</strong> the American Research Center in Egypt 197: 1–4.<br />

———. 2013. Sources for the study <strong>of</strong> L<strong>at</strong>e <strong>An</strong>tique and early Medieval <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong>. In<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

61<br />

Christianity and monasticism in Aswan and Nubia, G. Gabra and H. N. Takla (eds), 237–48.<br />

Cairo.<br />

Pinch, G. 1993. Votive <strong>of</strong>ferings to H<strong>at</strong>hor. Oxford.<br />

Quirke, S. and J. Spencer (eds) 1992. <strong>The</strong> <strong>British</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> book <strong>of</strong> ancient Egypt. London.<br />

Ranke, H. 1935. Die ägyptischen Personennamen I: Verzeichnis der Namen. Glückstadt.<br />

Robins, G. 2001. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> the squared grid as a technical aid for artists in Eighteenth<br />

Dynasty painted <strong>The</strong>ban tombs. In Colour and painting in ancient Egypt, W. V. Davies (ed.),<br />

60–62. London.<br />

———. 2010. Space and movement in pre-Amarna Eighteenth Dynasty <strong>The</strong>ban tombchapels.<br />

In Egyptian culture and society: Studies in honour <strong>of</strong> Naguib Kanaw<strong>at</strong>i, A. Woods, A.<br />

McFarlane and S. Binder (eds), 2: 129–42. CSASAE 38. Cairo.<br />

Ros<strong>at</strong>i, G. 2010. A rare formula on a Thirteenth Dynasty stela. In <strong>The</strong> Second Intermedi<strong>at</strong>e Period<br />

(Thirteenth–Seventeenth Dynasties): Current research, future prospects, M. Marée (ed.), 85–90. OLA<br />

192. Leuven; Paris; Walpole.<br />

Säve-Söderbergh, T. 1953. On Egyptian represent<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> hippopotamus hunting as a religious motive.<br />

Horae Soederblomianae 3. Uppsala.<br />

Sauneron, S. 1958. L’Ab<strong>at</strong>on de la campagne d’Esna. MDAIK 16: 271–79.<br />

Schmitz, F.-J. 1978. Amenophis I: Versuch einer Darstellung der Regierungszeit eines ägyptischen<br />

Herrschers der frühen 18. Dynastie. HÄB 6. Hildesheim.<br />

Seyfried, K.-J. 1995. Gener<strong>at</strong>ioneneinbindung. In <strong>The</strong>banische Beamtennekropolen: Neue Perspektiven<br />

archäologischer Forschung. Intern<strong>at</strong>ionales Symposion Heidelberg 9.–13, 6. 1993, J. Assmann, E.<br />

Dziobek, H. Guksch and F. Kampp (eds), 219–31. SAGA 12. Heidelberg.<br />

———. 2003. Reminiscences <strong>of</strong> the ‘Butic burial’ in <strong>The</strong>ban tombs <strong>of</strong> the New Kingdom.<br />

In <strong>The</strong> <strong>The</strong>ban Necropolis: Past, present and future, N. Strudwick and J. H. Taylor (eds), 61–68.<br />

London.<br />

Spieser, C. 2000. Les noms du Pharaon comme êtres autonomes au Nouvel Empire. OBO 174. Fribourg.<br />

Tylor, J. J. 1900. Wall drawings and monuments <strong>of</strong> El Kab: <strong>The</strong> tomb <strong>of</strong> Renni. London.<br />

Vandersleyen, C. 2005. L’Égypte et la vallée du Nil 2: De la fin de l’<strong>An</strong>cien Empire à la fin du Nouvel<br />

Empire. Paris.<br />

Vernus, P. 1986. Le surnom au Moyen Empire: Répertoire, procédés d’expression et structures de la double<br />

identité du début de la XIIe dynastie à la fin de la XVIIe dynastie. Studia Pohl 13. Rome.<br />

Werbrouck, M. 1940–1954. Quelques monuments d’Amenophis Ier à El Kab. In Fouilles de El<br />

Kab: Documents, Fond<strong>at</strong>ion égyptologique reine Élisabeth, 99–102. Brussels.<br />

Wessetzky, V. 1993. Une stèle d’Horus d’Edfou et de la déesse Hédédet. Bulletin du Musée<br />

Hongrois des Beaux-Arts, Budapest 79: 7–10.<br />

Whale, S. 1989. <strong>The</strong> family in the Eighteenth Dynasty <strong>of</strong> Egypt: A study <strong>of</strong> the represent<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> the family<br />

in priv<strong>at</strong>e tombs. ACE 1. Sydney.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

62 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 1: S<strong>at</strong>ellite image <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Edfu</strong> region (DigitalGlobe).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

63<br />

Fig. 2: View <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> <strong>Tomb</strong>s 1 and 2 (Photo: W. V. Davies).<br />

Fig. 3: View <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> <strong>Tomb</strong> 3 (Photo: W. V. Davies).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

64 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 4: Map <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hagr</strong> <strong>Edfu</strong> (F. Jarecki and A. Schmidt).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

65<br />

Fig. 5: Ground-plan <strong>of</strong> HE <strong>Tomb</strong>s 1–3 (G. Heindl).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

66 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 6: Façade <strong>of</strong> HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1 (Photo: W. V. Davies).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

67<br />

Fig. 7: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, doorway, northern reveal (Photo: W. V. Davies).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

68 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 8: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, interior, east wall (Photo: Y. Kobylecki).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

69<br />

Fig. 9: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, east wall, left, detail <strong>of</strong> hunting scene.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

70 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 10: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, north wall, left (Photo: Y. Kobylecki).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

71<br />

Fig. 11: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, north wall, right (Photo: Y. Kobylecki).<br />

Fig. 12: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, north wall, section <strong>of</strong> frieze-inscription.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

72 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 13: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, north wall, detail (Photo: W. V. Davies).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

73<br />

Fig. 14: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, north wall, figure <strong>of</strong> drummer.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

74 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 15: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, south wall, right (Photo: Y. Kobylecki).<br />

Fig. 16: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, south wall, left (Photo: Y. Kobylecki).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

75<br />

Fig. 17: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, niche (Photo: Y. Kobylecki).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

76 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 18: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, niche-façade, left jamb, inscription.<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

77<br />

Fig. 19: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, niche interior, south wall (Photo: J. Rossiter).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

78 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 20: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, niche interior, south wall, left (Photo: Y. Kobylecki).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

2013 SATAIMAU<br />

79<br />

Fig. 21: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, niche interior, north wall (Photo: J. Rossiter).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx

80 DAVIES BMSAES 20<br />

Fig. 22: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, niche interior, north wall, centre (Photo: Y. Kobylecki).<br />

Fig. 23: HE <strong>Tomb</strong> 1, niche interior, north wall, inscription as recorded on transparent acet<strong>at</strong>e<br />

(Photo: W. V. Davies).<br />

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_journals/bmsaes/issue_20/davies2013.aspx