Negative Concord in Modern Israeli Hebrew and its Origin

Negative Concord in Modern Israeli Hebrew and its Origin

Negative Concord in Modern Israeli Hebrew and its Origin

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

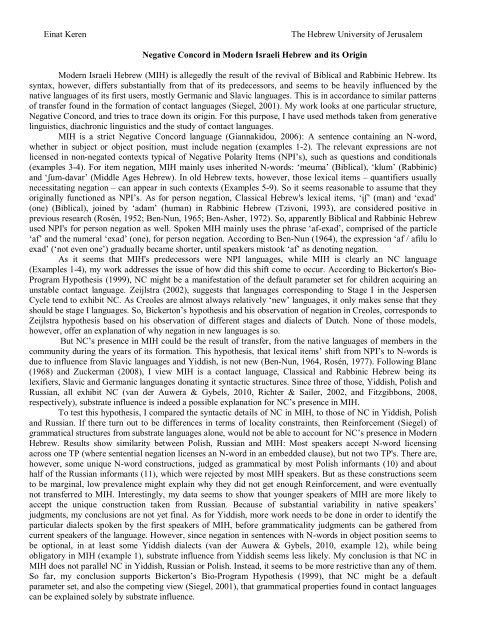

E<strong>in</strong>at Keren<br />

The <strong>Hebrew</strong> University of Jerusalem<br />

<strong>Negative</strong> <strong>Concord</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Israeli</strong> <strong>Hebrew</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>its</strong> Orig<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Israeli</strong> <strong>Hebrew</strong> (MIH) is allegedly the result of the revival of Biblical <strong>and</strong> Rabb<strong>in</strong>ic <strong>Hebrew</strong>. Its<br />

syntax, however, differs substantially from that of <strong>its</strong> predecessors, <strong>and</strong> seems to be heavily <strong>in</strong>fluenced by the<br />

native languages of <strong>its</strong> first users, mostly Germanic <strong>and</strong> Slavic languages. This is <strong>in</strong> accordance to similar patterns<br />

of transfer found <strong>in</strong> the formation of contact languages (Siegel, 2001). My work looks at one particular structure,<br />

<strong>Negative</strong> <strong>Concord</strong>, <strong>and</strong> tries to trace down <strong>its</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>. For this purpose, I have used methods taken from generative<br />

l<strong>in</strong>guistics, diachronic l<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>and</strong> the study of contact languages.<br />

MIH is a strict <strong>Negative</strong> <strong>Concord</strong> language (Giannakidou, 2006): A sentence conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g an N-word,<br />

whether <strong>in</strong> subject or object position, must <strong>in</strong>clude negation (examples 1-2). The relevant expressions are not<br />

licensed <strong>in</strong> non-negated contexts typical of <strong>Negative</strong> Polarity Items (NPI‟s), such as questions <strong>and</strong> conditionals<br />

(examples 3-4). For item negation, MIH ma<strong>in</strong>ly uses <strong>in</strong>herited N-words: „meuma‟ (Biblical), „klum‟ (Rabb<strong>in</strong>ic)<br />

<strong>and</strong> „ʃum-davar‟ (Middle Ages <strong>Hebrew</strong>). In old <strong>Hebrew</strong> texts, however, those lexical items – quantifiers usually<br />

necessitat<strong>in</strong>g negation – can appear <strong>in</strong> such contexts (Examples 5-9). So it seems reasonable to assume that they<br />

orig<strong>in</strong>ally functioned as NPI‟s. As for person negation, Classical <strong>Hebrew</strong>'s lexical items, „iʃ‟ (man) <strong>and</strong> „exad‟<br />

(one) (Biblical), jo<strong>in</strong>ed by „adam‟ (human) <strong>in</strong> Rabb<strong>in</strong>ic <strong>Hebrew</strong> (Tzivoni, 1993), are considered positive <strong>in</strong><br />

previous research (Rosén, 1952; Ben-Nun, 1965; Ben-Asher, 1972). So, apparently Biblical <strong>and</strong> Rabb<strong>in</strong>ic <strong>Hebrew</strong><br />

used NPI's for person negation as well. Spoken MIH ma<strong>in</strong>ly uses the phrase „af-exad‟, comprised of the particle<br />

„af‟ <strong>and</strong> the numeral „exad‟ (one), for person negation. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Ben-Nun (1964), the expression „af / afilu lo<br />

exad‟ („not even one‟) gradually became shorter, until speakers mistook „af‟ as denot<strong>in</strong>g negation.<br />

As it seems that MIH's predecessors were NPI languages, while MIH is clearly an NC language<br />

(Examples 1-4), my work addresses the issue of how did this shift come to occur. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Bickerton's Bio-<br />

Program Hypothesis (1999), NC might be a manifestation of the default parameter set for children acquir<strong>in</strong>g an<br />

unstable contact language. Zeijlstra (2002), suggests that languages correspond<strong>in</strong>g to Stage I <strong>in</strong> the Jespersen<br />

Cycle tend to exhibit NC. As Creoles are almost always relatively „new‟ languages, it only makes sense that they<br />

should be stage I languages. So, Bickerton‟s hypothesis <strong>and</strong> his observation of negation <strong>in</strong> Creoles, corresponds to<br />

Zeijlstra hypothesis based on his observation of different stages <strong>and</strong> dialects of Dutch. None of those models,<br />

however, offer an explanation of why negation <strong>in</strong> new languages is so.<br />

But NC‟s presence <strong>in</strong> MIH could be the result of transfer, from the native languages of members <strong>in</strong> the<br />

community dur<strong>in</strong>g the years of <strong>its</strong> formation. This hypothesis, that lexical items‟ shift from NPI‟s to N-words is<br />

due to <strong>in</strong>fluence from Slavic languages <strong>and</strong> Yiddish, is not new (Ben-Nun, 1964, Rosén, 1977). Follow<strong>in</strong>g Blanc<br />

(1968) <strong>and</strong> Zuckerman (2008), I view MIH is a contact language, Classical <strong>and</strong> Rabb<strong>in</strong>ic <strong>Hebrew</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>its</strong><br />

lexifiers, Slavic <strong>and</strong> Germanic languages donat<strong>in</strong>g it syntactic structures. S<strong>in</strong>ce three of those, Yiddish, Polish <strong>and</strong><br />

Russian, all exhibit NC (van der Auwera & Gybels, 2010, Richter & Sailer, 2002, <strong>and</strong> Fitzgibbons, 2008,<br />

respectively), substrate <strong>in</strong>fluence is <strong>in</strong>deed a possible explanation for NC‟s presence <strong>in</strong> MIH.<br />

To test this hypothesis, I compared the syntactic details of NC <strong>in</strong> MIH, to those of NC <strong>in</strong> Yiddish, Polish<br />

<strong>and</strong> Russian. If there turn out to be differences <strong>in</strong> terms of locality constra<strong>in</strong>ts, then Re<strong>in</strong>forcement (Siegel) of<br />

grammatical structures from substrate languages alone, would not be able to account for NC‟s presence <strong>in</strong> <strong>Modern</strong><br />

<strong>Hebrew</strong>. Results show similarity between Polish, Russian <strong>and</strong> MIH: Most speakers accept N-word licens<strong>in</strong>g<br />

across one TP (where sentential negation licenses an N-word <strong>in</strong> an embedded clause), but not two TP's. There are,<br />

however, some unique N-word constructions, judged as grammatical by most Polish <strong>in</strong>formants (10) <strong>and</strong> about<br />

half of the Russian <strong>in</strong>formants (11), which were rejected by most MIH speakers. But as these constructions seem<br />

to be marg<strong>in</strong>al, low prevalence might expla<strong>in</strong> why they did not get enough Re<strong>in</strong>forcement, <strong>and</strong> were eventually<br />

not transferred to MIH. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, my data seems to show that younger speakers of MIH are more likely to<br />

accept the unique construction taken from Russian. Because of substantial variability <strong>in</strong> native speakers‟<br />

judgments, my conclusions are not yet f<strong>in</strong>al. As for Yiddish, more work needs to be done <strong>in</strong> order to identify the<br />

particular dialects spoken by the first speakers of MIH, before grammaticality judgments can be gathered from<br />

current speakers of the language. However, s<strong>in</strong>ce negation <strong>in</strong> sentences with N-words <strong>in</strong> object position seems to<br />

be optional, <strong>in</strong> at least some Yiddish dialects (van der Auwera & Gybels, 2010, example 12), while be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

obligatory <strong>in</strong> MIH (example 1), substrate <strong>in</strong>fluence from Yiddish seems less likely. My conclusion is that NC <strong>in</strong><br />

MIH does not parallel NC <strong>in</strong> Yiddish, Russian or Polish. Instead, it seems to be more restrictive than any of them.<br />

So far, my conclusion supports Bickerton‟s Bio-Program Hypothesis (1999), that NC might be a default<br />

parameter set, <strong>and</strong> also the compet<strong>in</strong>g view (Siegel, 2001), that grammatical properties found <strong>in</strong> contact languages<br />

can be expla<strong>in</strong>ed solely by substrate <strong>in</strong>fluence.

Examples<br />

1. *(lo) ra‟iti af-exad (<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

no see- PAST -1s af-exad<br />

I didn‟t see anybody / I saw no-one<br />

2. af-exad *(lo) ra‟a oti (<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

af-exad no see- PAST -sm ACC-1s<br />

Nobody has seen me<br />

3. *ra‟ita af-exad? (<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

see- PAST -2sm af-exad<br />

Did you see anyone?<br />

4. *„im tir‟e af-exad, tagid lo… (<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

if see-2sm af-exad tell- FUTURE -2sm to-him<br />

If you happen to see anyone, tell him…<br />

5. …h<strong>in</strong>e ba‟ti elaixa „ata ha-yaxol uxal daber (Biblical <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

…here come-1s to-you-sm now Q-can-<strong>in</strong>f can-1s talk-<strong>in</strong>f<br />

meuma ha-davar aʃer yasim elohim be-fi oto adaber<br />

meuma the-th<strong>in</strong>g that put-sm god <strong>in</strong>-mouth-m<strong>in</strong>e-sm ACC-sm speak-1s<br />

“…Lo, I am come unto thee: have I now any power at all to say any th<strong>in</strong>g? the word that God putteth <strong>in</strong> my mouth,<br />

that shall I speak” (Numbers, 22, 38)<br />

6. ki taʃe be-re‟axa maʃ‟at meuma lo tavo el- beito (Biblical <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

If lend-2sm <strong>in</strong>-friend-yours-m th<strong>in</strong>g meuma no come-2s to house-his-m<br />

la‟avot avoto<br />

take-<strong>in</strong>f pledge-his<br />

“When thou dost lend thy brother any th<strong>in</strong>g, thou shalt not go <strong>in</strong>to his house to fetch his pledge” (Deuteronomy,24,10)<br />

7. im yo‟mar lexa Yitro klum m<strong>in</strong> ha-ʃvu‟a emor lo… (Rabb<strong>in</strong>ic <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

if say-3s to-you-sm Jethro klum from the-oath say-imp-sm to-him<br />

“Should Jethro at all rem<strong>in</strong>d you of your oath, you can say…” (Midrash Rabbah – Exodus, IV, 4)<br />

8. ro‟im atem klum be-exad m<strong>in</strong> he-harim halalu? (Rabb<strong>in</strong>ic <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

see- PRES -pm you-pm klum <strong>in</strong>-one of the-mounta<strong>in</strong>s those?<br />

“…Do you see anyth<strong>in</strong>g upon one of those mounta<strong>in</strong>s?” (The chapters of Rabbi Eliezer the Great, chapter 31)<br />

9. ve-exad ʃe-sho‟el et ha-be‟alim le-ota ha-mla‟xa o … o le-ʃum-davar<br />

<strong>and</strong>-one-m that-borrow-sm ACC the-owners for- ACC -sf the-work-f or … or for-ʃum-davar<br />

ba-olam … harei zo ʃe‟ila ba-be‟alim ve-patur (Middle Ages <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

<strong>in</strong>-the-world-m… emphatic it-f borrow<strong>in</strong>g-f <strong>in</strong>-the-owners <strong>and</strong>-quit- PASS -3sm<br />

“whether the commodatory borrowed the services of the owner or hired them, whether he borrowed the services for<br />

the same work, … or for anyth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the world,… it is a case of borrow<strong>in</strong>g with the owner <strong>and</strong> the commadatory is<br />

quit.” Borrow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Deposit<strong>in</strong>g, 2, 1 (6), The book of civil laws, The code of Mimonides (Mishne Torah).<br />

10. Kocham ją jak żadną <strong>in</strong>ną (Polish)<br />

love-1 her like-from nobody-f else-sf<br />

*ani ohev ota kmo af-axat axeret (<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

I love-m ACC-sf like af-one-sf else-sf<br />

“I love her more than anybody else”, “I love her like I love nobody else” (Taken from Richter & Sailer, 2002)<br />

11. ?Ti ischez v nikuda (Russian)<br />

you disappeared to nowhere<br />

*ata ne‟elamta le- ʃum-makom (<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

you-ms disappear- PAST -2sm to ʃum-place<br />

“You disappeared to nowhere” (Taken from Fitzgibbons, 2008)<br />

12. Ikh her gornit. (Yiddish)<br />

I hear noth<strong>in</strong>g / not at all<br />

ani *(lo) some‟a klum (<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Hebrew</strong>)<br />

„I hear noth<strong>in</strong>g.‟ or „I don‟t hear at all.‟ (Taken from van der Auwera & Gybels, 2010)<br />

References<br />

Bickerton, Derek (1999). How to acquire language without positive evidence: What acquisitionists can learn from<br />

Creoles. <strong>in</strong> DeGraff, M. (ed.) Language Creation <strong>and</strong> Language Change. MIT Press.<br />

Blanc, Haim (1968). The <strong>Israeli</strong> Ko<strong>in</strong>e as an Emergent National St<strong>and</strong>ard. <strong>in</strong> Fishman, J.A., Ferguson, C.A. <strong>and</strong> Das-<br />

Gupta, J (eds.) Language Problems <strong>in</strong> Develop<strong>in</strong>g Nation. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York.

Fitzgibbons, Natalia V. (2008) Freest<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>Negative</strong> <strong>Concord</strong> Items <strong>in</strong> Russian. Nanzan L<strong>in</strong>guistics: Special Issue 3,<br />

Vol. 2. (pp 51–63)<br />

Giannakidou, Anastasia (2006). N-words <strong>and</strong> negative concord. <strong>in</strong> van Riemsdijk, H, et al. (eds.). The syntax companion,<br />

Oxford: Blackwell, 327-391.<br />

Richter, Franc, & Sailer, Manfred. (2002) Polish Negation <strong>and</strong> Lexical Resource Semantics. Electronic Notes <strong>in</strong><br />

Theoretical Computer Science, Vol. 53.<br />

Rosén, Haiim B. (1977). Contemporary <strong>Hebrew</strong>. In W<strong>in</strong>ter, W. (ed) Trends <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, State-of-the Art Reports.<br />

Mouton & Co. B.V., Publishers, The Hague: Paris / Hungary.<br />

Siegel, Jeff (2001). Ko<strong>in</strong>e formation <strong>and</strong> creole genesis. <strong>in</strong> Smith, N. <strong>and</strong> Veenstra, T. (eds.) Creolization <strong>and</strong> Contact.<br />

Creole Language Library, 23, John Benjam<strong>in</strong>s Publish<strong>in</strong>g Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia. pp 175-197.<br />

van-der Auwera, Johan, <strong>and</strong> Gybels, Paul (2010). On negation, <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ites, <strong>and</strong> negative <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ites <strong>in</strong> Yiddish.<br />

URL: http://webh01.ua.ac.be/vdauwera/Neg%20<strong>in</strong>def%20Yid%20Aug%202010.pdf<br />

Zeijlstra, Hedde H. (2002), What the Dutch Jespersen Cycle may reveal about negative concord, <strong>in</strong> Alexiadou, A.,<br />

Fischer, S. <strong>and</strong> Stavrou, M. (eds.) L<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>in</strong> Potsdam, Vol. 19 (pp. 183–206)<br />

בן-נון, יחיאל )תשכ"ה(. כינוי השלילה. לשוננו לעם: טז, ד<br />

צבעוני, לאה דרכי השלילה בעברית הישראלית. חיבור לשם קבלת התואר דוקטור לפילוסופיה. האוניברסיטה העברית בירושלים.<br />

צוקרמן, גלעד ישראלית שפה יפה. הוצאת ספרים עם עובד, תל-אביב.<br />

רוזן, חיים ב. )תשי"ב(. תהליכי לשון – עיונים בתופעות העברית המדוברת. לשוננו לעם: ג, ג (כ"ה). 1-11<br />

)קס"ב(. 152-162.<br />

.)2991(<br />

.)1002(