Singapore 2012 Educational Programme Session 1 - International ...

Singapore 2012 Educational Programme Session 1 - International ...

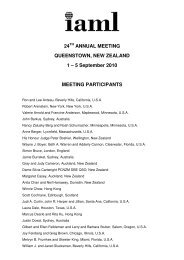

Singapore 2012 Educational Programme Session 1 - International ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

<strong>Educational</strong> <strong>Programme</strong><br />

<strong>Session</strong> 1<br />

Introduction to <strong>Singapore</strong><br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 1

FOO SIEW FONG<br />

Harry Elias Partnership<br />

SGX Centre 2, #17-01<br />

4 Shenton Way 068807<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong><br />

Tel: + 65 6535 0550<br />

Fax: + 65 6438 0550<br />

Email: siewfong@harryelias.com.sg<br />

Website: www.harryelias.com<br />

Head, Family and Matrimonial Law<br />

Head, Private Client and Wealth Management<br />

Siew Fong heads the Family and Matrimonial Law Practice Group and the<br />

Private Client and Wealth Management Practice Group. Siew Fong deals with<br />

all aspects of family and matrimonial law.<br />

The practice group was nominated the "Best Matrimonial Practice" by the<br />

Asian Legal Business Awards in 2002. In the same year, Asian Legal<br />

Business named Siew Fong as one of <strong>Singapore</strong>'s pre-eminent family law<br />

practitioners in their Legal Who's Who. In November 2011, the Family and<br />

Juvenile Justice Division awarded the Outstanding Volunteer of the Year in<br />

the Advocate and Solicitor Category to Siew Fong.<br />

Siew Fong also handles preventive issues at the beginning of a relationship,<br />

e.g. the preparation of pre-nuptial agreements and has been invited to sit on<br />

panels, national radio and television programmes where she shares her<br />

experience on the usual issues arising in divorce, assets and children.<br />

Siew Fong has been the President of the <strong>Singapore</strong> Association of Women's<br />

Lawyers (SAWL) from 2001 to 2009 and is now the honorary advisor to<br />

SAWL. She played a significant role in the publication "You and The Law",<br />

and "Teens and The Law". She is the author of "When Marriages Break<br />

Down:- Rights Obligations And Division of Property", a publication by Sweet &<br />

Maxwell and was recently appointed a member of the Committee by the Chief<br />

Justice under Section 139 (1) of the Women's Charter.<br />

Siew Fong's commitment to social work also sees her appointment as a<br />

council member with the South East Community Development Council as well<br />

as a Deputy Registrar/Licensed Solemniser by the Registry of Marriages.<br />

Siew Fong is also a member of the <strong>International</strong> Academy of Matrimonial<br />

Lawyers, which membership is open only to family lawyers with experience in<br />

international disputes relating to maintenance, division of assets and<br />

children's issues. She is also an accredited <strong>Singapore</strong> Mediation Centre<br />

family law mediator involved in the <strong>Singapore</strong> Mediation Centre's Family Law<br />

Mediation Pilot Project. She is a member of the executive committee of The<br />

Spastic Children's Association of <strong>Singapore</strong>, an organization that provides<br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 2

medical treatment and therapy for children with cerebral palsy, as well as<br />

vocational training and gainful employment through its school. She has also<br />

been recently appointed as a board member of the Brahm Centre, a<br />

registered charity dedicated to offering education programs and activities that<br />

promote happy and healthy living.<br />

Siew Fong remains committed to the progress of the legal community in<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong> too. She has been appointed to participate in the Committee for<br />

Continuing Professional Development Accreditation, a new scheme to be<br />

implemented by <strong>Singapore</strong> Institute of Legal Education that seeks to set<br />

progressive benchmarks for practitioners in the local legal landscape.<br />

Siew Fong was called to the <strong>Singapore</strong> Bar in 1991.<br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 3

<strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

<strong>Educational</strong> <strong>Programme</strong>: Thursday 6 th September <strong>2012</strong><br />

Introduction to <strong>Singapore</strong> brief history; family law in Asia & recent<br />

developments<br />

By Siew Fong Foo<br />

Harry Elias Partnership<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong><br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 4

TABLE OF CONTENTS <br />

Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..............................................................2 <br />

History of <strong>Singapore</strong> ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 <br />

Geography of <strong>Singapore</strong> ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 <br />

Matters of legal and cultural significance……………………………………………………………………………………….5 <br />

The development of family law in a common law country …………………………………………………5 <br />

Women’s Charter ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 <br />

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 <br />

Content of the Women’s Charter …………………………………………………………………………..6 <br />

Structure of <strong>Singapore</strong>’s family law system ………………………………………………………………………7 <br />

The Family Court ………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 <br />

The Shariah Court ………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 <br />

Ancillary Matters……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..9 <br />

Custody, care and control and access to children/maintenance…………………………….10 <br />

Maintenance……………………………………………………………………………………………………….11 <br />

Division of Matrimonial asserts…………………………………………………………………………….12 <br />

Family Law in Asia…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..13 <br />

Malaysia……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..13 <br />

Indonesia…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….15 <br />

Thailand………………………………………………………………………………………………………………17 <br />

China…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..19 <br />

Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………21 <br />

1 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 5

Abstract<br />

This paper was written to give an overview of<br />

family law in <strong>Singapore</strong>. It provides a background<br />

outlining how <strong>Singapore</strong> has arrived at where it is<br />

today with the Women's Charter- the reigning Act<br />

for all civil family law matters.<br />

Divorce, the division of matrimonial assets,<br />

maintenance, care and custody, and protection<br />

orders are just some of the areas governed by the<br />

The importance of family is highly<br />

valued in <strong>Singapore</strong>an society. <br />

Women's Charter. The Family Court, a specialised one-stop forum for litigants to seek<br />

aid for all family-related disputes, regulates the abovementioned aspects of law. For<br />

Muslims, there is the Shariah Court which applies Islamic law in addressing their family<br />

issues.<br />

Ancillary matters are always the cause of much conflict and have to be handled in<br />

a delicate manner. In dividing matrimonial assets, the courts take into account all<br />

of the parties' contributions, including non-financial contributions such as care for<br />

the children and the manning of household. Courts have been inclined to order<br />

shared custody of the children, with the desire to protect family obligations<br />

despite the closure of the marriage. In deciding on the sum of maintenance, the<br />

court seeks to preserve the lifestyle of the wife prior to the breakdown of the<br />

marriage.<br />

As with the Women’s Charter in <strong>Singapore</strong>, many other predominantly patriarchal<br />

Asian countries have also passed statutes to champion women’s rights and abolish<br />

polygamy. As such, regionally, family law has greatly progressed towards<br />

achieving fairer outcomes for matrimonial parties.<br />

2 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 6

History of <strong>Singapore</strong><br />

<strong>Singapore</strong> has a diverse history having been ruled by a Srivijayan prince, a British<br />

colonial administrator, conquered by Japanese forces, merged with Malaysia, and<br />

subsequently established as an independent nation on 9 August 1965.<br />

The young nation is 47 years old this year.<br />

14 th Century to the Present<br />

1891: Sir<br />

1800s:<br />

Stamford Raffles<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong> was a<br />

landed on the<br />

minute trading<br />

island, and it was<br />

port under the <br />

ruled by British <br />

rule of a Srlyijavan<br />

colonial powers.<br />

prince.<br />

1 94 2 -1945<br />

World War II<br />

resulted in the<br />

conquer of<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong> by the<br />

Japanese.<br />

1963: The British<br />

gradually <br />

diminished their<br />

control over<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong>, and<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong> merged<br />

with Malaya to<br />

from Malaysia.<br />

1965-<strong>2012</strong><br />

<strong>Singapore</strong> broke<br />

away as an<br />

independent<br />

nation and<br />

became known as<br />

the Republic of<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong>.<br />

3 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 7

Geography of <strong>Singapore</strong><br />

<strong>Singapore</strong> is a small island nation of approximately 275.79 square miles (or<br />

714.3 square km), making it half the size of New York City. Notwithstanding<br />

the modest land area, the island boasts a whopping five million people,<br />

amounting to a population density of 2,801 people per square mile (or 7,257<br />

people per square km). It has been consistently referred to as the "Little Red<br />

Dot", a symbol of the nation's continuous success despite its physical<br />

limitations. <br />

<strong>Singapore</strong> is part of Southeast Asia and it is surrounded by neighbouring<br />

such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Philippines.<br />

Department of Statistics <strong>Singapore</strong> website :http://www.singstat.gov.sg/stats/keyind.html<br />

4 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 8

Matters of legal and cultural significance<br />

A) The development of family law in a common law country<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong> used to be a Crown colony under the powers of Britain. Inevitably,<br />

when the legal system in <strong>Singapore</strong> was first established, a partial adoption of the<br />

relevant English laws took place: English common law rules were made to<br />

govern marriages, as well as inter-spousal relationships. However some of the<br />

English laws were subjected to modifications to better suit the multi-cultural society<br />

of <strong>Singapore</strong>. This allowed religious beliefs and customs of the local inhabitants to<br />

be factored into the prevailing law 1 .<br />

Nevertheless, the multifarious process of encompassing local modifications by the<br />

Straits Settlements' judges caused a distortion of common law with local customary<br />

traditions and the resulting judicial principles were not substantial enough for a<br />

body of family law to be created.<br />

Family law in the 19 th and early 20 th century was in a lamentable state.<br />

B) Women's Charter 2<br />

(1) Introduction<br />

Prior to the Women's Charter being enacted, the regime in place was drastically<br />

unequal and there was nothing in law to protect the rights of the women of<br />

<strong>Singapore</strong>. At that time, Chinese and Hindu men could legally marry multiple<br />

wives, women were not allowed to keep their maiden names, and divorce did not<br />

accord the women any rights out of the marriage 3 . All these were permitted by the<br />

different ethnic groups' respective customary traditions, which were clearly<br />

posing unacceptable restrictions on the welfare of women.<br />

1 Halsbury's Laws of <strong>Singapore</strong> Volume 11 (LexisNexis, 2006 Reissue) at para 130.007.<br />

2 Women's Charter (Cap 353, 2009 Rev Ed).<br />

3 Foo Siew Fong, When Marriages Break Down: Rights, Obligations and Division of Property, at p 5. <br />

5 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 9

There was a need to secure the rights and elevate the status of women, such that<br />

they would be accorded protection in a society that had been primarily dominated<br />

by males. The Women's Charter was enacted to accomplish this goal.<br />

In 1961, this Act was enacted and a radical change to family life and the marriage<br />

system occurred — both men and women can only marry a single spouse of the<br />

opposite gender legally, and legal protection is now afforded to divorced women<br />

and girls alike.<br />

At present, family law in <strong>Singapore</strong> is governed by both statutes and the common<br />

law, of which the latter supplements the former and allows for incremental<br />

development of the law.<br />

(2) Content of the Women's Charter<br />

The Women's Charter has successfully achieved the protection of the rights of<br />

women and girls in <strong>Singapore</strong>. By regulating the formation and termination of<br />

marriage, the spousal relationship and some of the economic aspects of family<br />

life 4 , the Women's Charter has enhanced the quality of life for married and divorced<br />

women. Furthermore, it provides for the punishment of offences against women and<br />

girls, affording them protection in the face of aggression.<br />

Divorce as governed by the Women's Charter has one ground: the irretrievable<br />

breakdown of the marriage. There are five separate ways to establish this proof<br />

of ground - adultery, unreasonable behaviour, desertion of two years, separation<br />

for three years with consent, and separation for four years. It is important to note<br />

that the quick exit of irreconcilable differences, whereby one can divorce their<br />

spouse due to character and lifestyle differences, is not found in the Women's<br />

Charter.<br />

4 Halsbury's Laws of <strong>Singapore</strong>, supra n 2 at Para 130.016.<br />

6 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 10

C) Structure of <strong>Singapore</strong>’s family law system<br />

In <strong>Singapore</strong>, family law is administered by both the civil Family Court and the<br />

Shariah Court. This is because the laws regulating certain aspects of family life – for<br />

example the formation of marriage, the termination of marriage and the<br />

relationship between spouses, are different for non-Muslims and Muslims. There is a<br />

need for this as religious matters must be handled with a high degree of sensitivity to<br />

preserve the harmony enjoyed by this multicultural nation. As such, <strong>Singapore</strong> is<br />

certainly a prime example of how religious law is applied in a secular state.<br />

(1) The Family Court<br />

In 1995, the Family Court was established as a branch of the Subordinate<br />

Courts. This move consolidated the jurisdiction of the Subordinate Courts to a<br />

single court for the hearing and resolution of disputes concerning family law.<br />

Previously, the hearing of family law disputes was dispersed between the<br />

various courts.<br />

The Family Court possesses unrestricted exclusive jurisdiction over all non-<br />

Muslim persons 5 . Civil law administered by the Family Court is found in the<br />

Women's Charter, the general law which family matters are governed by. The<br />

court exercises authority over divorce, applications for maintenance, family<br />

protection, adoption, guardianship of children, annulment, judicial separation,<br />

protection orders, and the ancillary applications for maintenance, custody, and the<br />

division of matrimonial assets 6 .<br />

The congregation of all family matters at a core point and the fusion of the<br />

relevant social services with legal processes allows for specialization, which<br />

benefits parties that have come to the Family Court in need of services. This swift<br />

and effective resolution of issues also decreases animosity between parties. In<br />

light of working towards strengthening and preserving family ties, the courts may<br />

5 Women's Charter (Cap 353, 2009 Rev Ed) ss 3(1) — (2).<br />

6 Halsbury's Laws of <strong>Singapore</strong>, supra n 2 at para 130.021 <br />

7 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 11

ecommend mediation and counseling for the parties to settle their family disputes<br />

harmoniously. Further, a unified Family Court ensures that applications are<br />

processed more efficiently, resulting in cost savings for the litigants.<br />

Some parts of non-Muslim family law may govern Muslims in areas of family<br />

law 7 such that both the Family Court and Shariah Court have concurrent<br />

jurisdiction over the Muslims. Such jurisdiction is usually in relation to<br />

ancillary matters.<br />

(2) The Shariah Court<br />

The Shariah Court possesses exclusive jurisdiction over Muslim persons in<br />

areas of family life. This exclusive jurisdiction is derived from the<br />

Administration of Muslim Law Act ("AMLA") 8 . Muslim family law administered<br />

by the Shariah Court consists of Islamic theology derived from the Koran,<br />

Sunnah, ijma, qiyas and other secondary sources. The substantive provisions<br />

of the AMLA and Malay customs have been incorporated into local law.<br />

In Islam, divorce is generally discouraged and substantive reasons need to be<br />

provided before a married couple may resort to divorce 9 . In the Koran, there<br />

is a verse that when translated means "retain her on reasonable terms or<br />

release her with kindness". Hence, it is only when staying together is more<br />

harmful than being apart will the Koran condone divorce and make it lawful.<br />

There are different types of divorces in Islam, primarily the Talak, which<br />

caters to the husband's rights, and the Khulu', which caters to the wife's<br />

rights.<br />

The Talak is an intriguing form of divorce founded in Islam. It consists of an<br />

utterance by the husband that repudiates or cuts off the marital tie, following<br />

7 E.g. maintenance claims for Muslim divorces can be made in the Family Court in accordance with s 69 of the<br />

Women's Charter that applies to Muslims as well (with the exception that divorced Muslim women have to apply<br />

to the Sharjah Court for maintenance), applications for the division of matrimonial assets, applications for care<br />

and custody for any child and the filing of personal protection orders etc.<br />

8 Administration of Muslim Law Act (Cap 3, 2009 Rev Ed.).<br />

9 Syariah Court <strong>Singapore</strong> website<br />

<br />

8 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 12

which the husband and wife refrain from intimacy for a period of three menstrual<br />

cycles 10 . The purpose of this is to give the couple a period of reconciliation. If the<br />

husband allows this period to end, he would be considered to have divorced his<br />

wife, with or without her consent 11 .<br />

Another form of divorce that features in the Muslim community is the Khulu',<br />

which is requested by the wife. This form of divorce is effected by mutual<br />

agreement, whereby the wife will offer to pay a dowry sum to her husband. In<br />

return, the wife will be released from her marriage tie. It is a consensual<br />

divorce, and it can be argued that a Khulu' is voidable if it is demonstrated<br />

that either of the parties lacked consent or was induced into acceptance by<br />

severe fraud or duress 12 .<br />

Even though these are extrajudicial forms of divorce, Muslims continue to<br />

abide by these rules. In the AMLA, it is further legislated for the Muslim<br />

husband and wife to attend the Shariah Court personally within seven days of<br />

the divorce, furnish the particulars required, and apply for a decree or order<br />

for divorce in the prescribed form 13 .<br />

D) Ancillary matters<br />

While the divorcing parties have the autonomy in deciding matters such as<br />

parenting plans or the plans for division of matrimonial assets, the court<br />

ultimately remains the overarching body in overseeing such agreements.<br />

The parties are required to submit an agreed, if not proposed parenting plan<br />

along with the writ of divorce. The aim of this practice is to encourage parties<br />

to come to a prior agreement before the divorce petition even kicks off. This<br />

negotiation is, in effect, an opportunity for the parties to interact, highlighting<br />

the Family Court's slant towards mediation and reconciliation. 14<br />

Similarly,<br />

10 David Pearl, A Textbook on Muslim Personal Law, at p 100. <br />

11 Ibid.<br />

12 Id at 121.<br />

13 Administration of Muslim Law Act (Cap 3, 2009 Rev Ed.) s 102(5). <br />

14 Halsbury's Laws of <strong>Singapore</strong>, supra n 2 at para 130.326. <br />

9 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 13

when the matrimonial home is in the form of a public housing, the parties will<br />

have to fill in a Matrimonial Property Plan.<br />

In any event, if parties are unable to arrive at such an agreement, the court<br />

will, giving weight to all relevant and necessary circumstances, give an order<br />

on the ancillary matters; in particular, the custody, care and control and<br />

access of the children, the maintenance for the wife, and the division of the<br />

matrimonial home and assets. Crucially, in the division of assets, the Court will<br />

have regard to the needs of minor children.<br />

(1) Custody, care and control and access to children/Maintenance<br />

Given that the nature of issues pertaining to children is the most sensitive, the<br />

court will avoid making these issues acrimonious, lest the children become<br />

caught in an even uglier battle.<br />

'The issue of "custody" concerns the decision-making power over major<br />

aspects of the child's life i.e. which school the child should attend, which<br />

religion the child should embrace, and if the need arises, what medical care<br />

the child ought to receive.<br />

"Care and control" relates to day-to-day matters concerning the child's living<br />

arrangement, upbringing and well-being. The parent without care and control<br />

over the child will then be granted access rights 15 .<br />

Unless there are extremely extenuating circumstances, courts are more<br />

inclined to give orders of joint custody to both parents, with a firm belief that<br />

parental duties are ultimately a shared responsibility between both parents.<br />

This is in line with the Family Court's objective of preserving family ties.<br />

Care and control will be the responsibility of a sole parent, and as mentioned,<br />

the other parent will then have access rights to the child. Save for unique<br />

cases, for example, where the child has been abused by one parent, the courts<br />

15 Leong Wai Kum, 'Significant Provisions in the Women's Charter', in ch. 3 <strong>Singapore</strong> Women's Charter —<br />

Roles, Responsibilities and Rights in Marriage (2011). <br />

10 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 14

are disinclined from denying a parent access rights.<br />

(1)(a)Maintenance of Children<br />

How about the maintenance of the parties’ child/children? The Court has the<br />

power to order a parent to pay maintenance for the benefit of a child/children<br />

during the pendency of any matrimonial proceedings, or when granting it or any<br />

time subsequent to the grant of a judgment of divorce/judicial separation/nullity<br />

of marriage 16 . This child maintenance will relate to issues concerning<br />

accommodation, clothing, food and education.<br />

In general, maintenance for children will usually terminate when the child turns<br />

21; but this is subject to exceptions 17 , for example if the child is still schooling.<br />

(2) Maintenance<br />

Given that in a divorce parties seek to terminate the relationship with one<br />

another, the idea of maintenance which implies a continuing relationship is<br />

extremely contentious. The law seeks to ensure that the divorced wife receives<br />

maintenance. Maintenance is awarded on the basis of need in accordance with<br />

the principle of financial preservation.<br />

It is a common misconception that orders for maintenance are gender biased<br />

and tend to protect former wives. This is untrue, as the court will consider all<br />

circumstances of the case before coming to a decision. In particular, they will<br />

consider the wife's financial needs, her income and earning capacity, the age of<br />

the parties and the duration of the marriage, the contributions that she had<br />

made to the family, the conduct of each party to the marriage, and the<br />

standard of living enjoyed by the wife prior to the divorce during the course of<br />

the marriage. 18<br />

To date, one of the highest maintenance orders ever sought before the<br />

16 Women's Charter (Cap 353, 2009 Rev Ed) ss 123(1). <br />

17 Women's Charter (Cap 353, 2009 Rev Ed.) s 69(5).<br />

18 Women's Charter (Cap 353, 2009 Rev Ed.) s 69(4).<br />

11 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 15

<strong>Singapore</strong> court amounts to a staggering $450,000 19 . The request was made in<br />

accordance with the wife's monthly spending, and based on "actual historic<br />

payments" 20 with the view of maintaining the lifestyle she was used to.<br />

(3) Division of matrimonial assets<br />

What is the definition of “matrimonial assets”? Per S112 (10) of the Women's<br />

Charter, this is defined as any asset acquired before the marriage by one party or<br />

both parties to the marriage −<br />

(i)<br />

ordinarily used or enjoyed by both parties or one or more of their children<br />

while the parties are residing together for shelter or transportation or for<br />

household, education, recreational, social or aesthetic purpose; or<br />

(ii)<br />

which has been substantially improved during the marriage by the other<br />

party or by both parties to the marriage;<br />

(iii)<br />

and any other asset of any nature acquired during the marriage by one<br />

party or both parties to the marriage<br />

This however excludes any gift or inheritance by either party. As such, the Women’s<br />

Charter makes it clear that a matrimonial home acquired before or after the<br />

marriage will be considered a “matrimonial asset” to be divided between the parties.<br />

The court is empowered to consider financial and non-financial contributions by both<br />

parties and needs of the children when making an order to divide the matrimonial<br />

assets between them, in a way it considers just and equitable. Factors that the<br />

court will consider include: needs of the minor children, monetary contributions by<br />

each party towards acquiring, improving or maintaining the matrimonial asset; any<br />

debt undertaken by the parties; the extent each party cared for the welfare of the<br />

family (non-financially) and the giving of non-material support by one party to<br />

another 21 .<br />

19 Chua Xin Yin v Nurdian Cuaca [2010] SGDC 540.<br />

20 Id at [26].1 <br />

21 Women's Charter (Cap 353, 2009 Rev Ed.) ss 112(1) — (2). <br />

12 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 16

Family Law in Asia<br />

I am not an expert in the family law regimes of other countries. However in<br />

this paper I have given an overview of the development of family law in<br />

Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and China- the significant attempts they have<br />

made in according greater rights to women and fairer outcomes in divorce<br />

proceedings.<br />

A) Malaysia<br />

Malaysia used to be part of the former British colony and boasts a similar legal<br />

landscape to that of <strong>Singapore</strong>. Prior to the enactment of the Law Reform<br />

(Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976 22 , non-Muslim citizens of Malaysia married<br />

according to their own respective customs, with various instruments of<br />

22 Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976, Act 164 (2006 Reprint).<br />

13 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 17

marriage solemnization in place 23 . For example, in the case of Christian<br />

marriages, Christians were advised to register their marriage under both the<br />

Christian Marriage Ordinance and the Civil Marriage Ordinance, the latter of<br />

which expressly disallows polygamy. Only then could Christian wives ensure<br />

that their marriage remained a monogamous one.<br />

Inevitably, the plurality of legislation led to many unenviable decisions and the<br />

enactment of the said Act (analogous to that of the Women's Charter) has thus<br />

come as a blessing to regulate customary marriages and consolidate an<br />

authority for non-Muslim family laws. The Act has also introduced a conciliation<br />

procedure for divorce, which is similar to the mediation that occurs before a<br />

divorce is petitioned in the United Kingdom.<br />

On the other hand, Muslim citizens have their Islamic law regime which is within<br />

the legislative authority of the State and administered by the Shariah courts 24 .<br />

Notwithstanding this, the Act has certainly improved the quality of marriage for<br />

non-Muslim women by codifying the Shariah 25 . The rights of women were spelt<br />

out for the first time, reducing the number of women ignorant of their legal<br />

rights. By tackling this problem, more women were aware of what conduct their<br />

Muslim husbands were permitted to engage in.<br />

Subsequently, the Islamic Family Law Act 1984 was passed to enact certain<br />

provisions of Islamic law in relation to marriage, divorce, maintenance,<br />

guardianship and other matters connected with family life. Islamic family law,<br />

though uniform in content, is diverse in its application in the various states of<br />

Malaysia 26 . Hence, further amendments have been made in an attempt to unify<br />

its application.<br />

It is worth noting that both the Act covering non-Muslim family laws and Muslim<br />

family laws have reached the same conclusion as to the manner in which property<br />

23 Mehrun Siraj, Women and the Law: Significant Developments in Malaysia, at p 561.<br />

24 Ibid.<br />

25 Mehrun Siraj, Women and the Law: Significant Developments in Malaysia, Law &Society Review vol 28 number<br />

3 at p565.<br />

26 Raihana Abdullah, A Study of Islamic Family Law in Malaysia: A Select Bibliography, <strong>International</strong> Journal of<br />

Legal Information vol 35 number 3 at p11.<br />

14 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 18

should be divided between husband and wife 27 ; that is by identifying the direct<br />

contributions and subsequent improvements made to the property and dividing the<br />

value of the property fairly.<br />

B) Indonesia<br />

As a former Dutch colony, Indonesia retains the legacy of Roman-Dutch law, as<br />

well as adat law which comprises unwritten customs of indigenous<br />

Indonesians before the Dutch colonial conquest. The amalgamation of these<br />

laws resulted in modern Indonesian law as we know of today. Indonesia, with<br />

90% of its population followers of the Islamic faith, is also the home of 202<br />

million Muslims of all ages 28 .<br />

27 Leong Wai Kum, "Book Reviews" SJLS [1998] at 205 — 207. <br />

28 Pew Research Centre, Mapping the Global Muslim Population 2009, at p 5.<br />

15 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 19

Unsurprisingly, pre-1974 Indonesian family law was in an extremely<br />

unsatisfactory state for women. There were laws condoning practices such as<br />

forced marriages, child marriages, polygamy, and a lack of consent for divorce.<br />

What may seem to us to be common marital rights, for example, maintenance,<br />

custody and child support, were unknown to Indonesian women.<br />

In 1974, the government passed a unified code for family law. This represented<br />

a major victory for Indonesian women who had been striving for emancipation<br />

for the past 45 years. Albeit an alleged form of political initiative towards the<br />

country's unification 29 , the unified code made significant inroads into marital<br />

affairs. Marital practices that were previously effected by the unilateral decision<br />

of the Muslim male and the mere registration of his intent now have to be<br />

sanctioned by the court.<br />

In polygamous marriages, the court requires the applicant to prove to the court<br />

that he had permission from his current wife or wives and that he had the ability<br />

to support the extension of his family 30 , thus substantiating the taking of more<br />

wives. Furthermore, divorce procedures were changed such that petitioners had<br />

to appear in court with reasons to justify the divorce. 31 The stipulation of a<br />

minimum age for marriage reduced child marriages as well 32 .<br />

Fundamentally, through the disincentive of having to seek prior approval from<br />

the courts, it has become significantly harder for a Muslim man to groundlessly<br />

attain a divorce and engage in polygamy 33 .<br />

The different states of Indonesia have similarly followed suit and implemented<br />

unification statutes of their own. These changes have transformed the lives of<br />

married women all over Indonesia, paving the way for better treatment of<br />

women and fairer judicial outcomes in divorce proceedings.<br />

29 June S. Katz and Ronald S. Katz, "The New Indonesian Marriage Law: A Mirror of Indonesia's Political, Cultural<br />

and Legal Systems", The American Journal of Comparative Law vol 23, No. 4 at p 681<br />

30 See New Marriage Law, Art 4 and 5 and Elucidation.<br />

31 Id. at Art 39(1) and 39(2).<br />

32 Id. at Art 7(1).<br />

33 June S. Katz and Ronald S. Katz, "Legislating Social Change in A Developing Country: The New Indonesian<br />

Marriage Law Revisited", The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol 26 No.2 at p 316.<br />

16 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 20

C) Thailand<br />

Unlike most of the other Southeast Asian nations, Thailand was never colonized.<br />

However, most of the laws in Thailand were modeled after a European style<br />

framework, containing elements of French civilian tradition coupled with German,<br />

Swiss and Japanese models.<br />

Perhaps the most significant part of the marriage laws in Thailand was that<br />

polygamy was legal until 1935. This meant that it was rather commonplace for<br />

men, particularly those from the upper class, to have several wives.<br />

Furthermore, men had the right to treat their wives as private property and<br />

inflict any punishment on them as he saw fit. The women's subservient position<br />

in the Thai society was further exacerbated by the men's power to manage all of<br />

17 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 21

his wives' monies and land that she had brought into the marriage 34 .<br />

The Monogamy Act was introduced in 1935 in a bid to curb the problems of<br />

polygamous marriages. However, inherent problems such as the inefficiencies of<br />

the central marriage registration system still meant that marriage inequalities<br />

remained prevalent.<br />

A turning point in Thailand family law came in the late 1960s when welleducated,<br />

outspoken females from the upper class of society spoke out against<br />

issues pertaining to matrimonial property management and the prevention of<br />

double marital registration. Their voices served as a catalyst for the increased<br />

emancipation of females in Thailand, in particular with regards to domestic<br />

violence and reproductive rights.<br />

Previously, both men and women had the right to divorce on judicial grounds;<br />

but, only men could divorce their wives on grounds of adultery, and not vice<br />

versa. Unless the woman was able to prove that her husband was in fact<br />

committing bigamy in providing for another woman as his mia not (minor wife),<br />

she would not be able to divorce her husband. In 2007, this law was revised<br />

such that both parties could divorce each other on the grounds of rape and<br />

adultery.<br />

Domestic violence, a somewhat commonplace occurrence in Thailand previously,<br />

was also tackled by the introduction of the Domestic Violence Victim Protection<br />

Act 2007 35 .<br />

As such, Thailand has greatly progressed in its development of family law and in<br />

according women greater rights.<br />

34 Dr Kanwafjit Soin, Keynote Address "Women's Charter to Family Charter", 10 June 2009.<br />

35 Domestic Violence Victime Protection Act, B.E. 2550 (2007).<br />

18 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 22

D) China<br />

Family and matrimonial law in China is governed by the Marriage Law 36 . Prior to<br />

the enactment of this provision in 1950, China was predominantly a patriarchal<br />

society. The dominance of men who enjoyed superior social status culminated in<br />

practices such as compulsory arranged marriages and the neglect of children's<br />

rights and interests. The enactment of the 1950 Marriage Law aimed at<br />

abolishing this prevalent problem.<br />

The Marriage Law was revised again in 1980, targeting issues such as the<br />

freedom of marriage, monogamy, equality between men and women and the<br />

protection of women and children's rights. More recently, in 2001, further<br />

amendments were made to the revised Marriage Law, in hopes of reducing<br />

instances of gender inequality upon which their society was founded on, and other<br />

deeply entrenched patriarchal practices.<br />

36 Charles ,i. Ogletree, Jr., Rangita de Silva-de Alwis, "The Recently Revised Marriage Law of China: The Promise<br />

and the Reality" (2004) 13 Tex. J. Women & L. 251.<br />

19 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 23

The issue of property rights in China remains a primary concern in the area of<br />

marriage law. Women's property rights are theoretically protected by<br />

constitutional and legislative guarantees. It is stipulated that properties obtained<br />

during the subsistence of marriage will belong to both husband and wife 37 ; at<br />

divorce, common property will be divided based on mutual agreement 38 . Further,<br />

if parties fail to reach an agreement in relation to the division of property, the<br />

court is inclined to make a division favouring the wife and child. However,<br />

despite these protective measures, weak enforcement mechanisms still results in<br />

women remaining largely disadvantaged when faced with issues of division of<br />

property. Moreover, rigidities in the allocation of houses in provinces and<br />

municipalities mean that the divorced women are usually at the lowest spectrum<br />

of eligibility for housing.<br />

The Revised Marriage Law makes domestic violence a ground both for divorce<br />

and for civil compensation at divorce. However, without a clear definition of<br />

what constitutes domestic violence, the honorable objectives behind this law<br />

have not been successfully achieved. For example unlike in <strong>Singapore</strong> 39 ,<br />

psychological injury caused by domestic violence is rarely an actionable wrong<br />

in China; only violence perpetrated by a current spouse is actionable.<br />

Conclusion<br />

The family structure forms the basis of our social fabric. As such, family law has<br />

37 Marriage Law, Article 17. <br />

38 Marriage Law, Article 39. <br />

39 Women’s Charter (Cap 353, 2009 Rev Ed) s64. <br />

20 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 24

een and always will be an important tenet of <strong>Singapore</strong>'s legal system. In a<br />

divorce, it is inevitable for parties to suffer from emotional scars and anguish.<br />

Children can hardly be said to be in a better state, seeing how they are often<br />

dragged into a tragic tug of war when it comes to matters of custody, care and<br />

control and access. As such, the law plays an extremely critical role in<br />

protecting parties to a divorce and what is most valuable to them —their family,<br />

children, and homes.<br />

What the Women's Charter has achieved for <strong>Singapore</strong>an women is unrivalled<br />

in the island's history and with the resolve of the Family Court and family<br />

lawyers, the best interests of these parties will be passionately fought in years<br />

to come.<br />

21 <br />

IAML <strong>Singapore</strong> <strong>2012</strong> Meeting Handbook <strong>Session</strong> 1 - Page 25