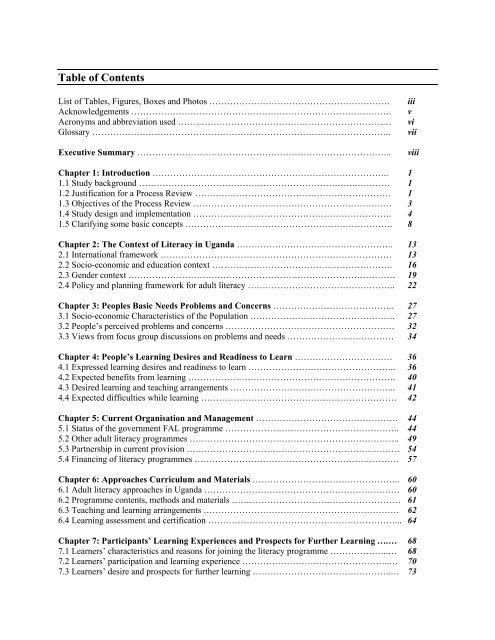

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Table</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contents</strong><br />

List <strong>of</strong> <strong>Table</strong>s, Figures, Boxes and Photos …………………………………………………….<br />

Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………………………….<br />

Acronyms and abbreviation used ………………………………………………………………<br />

Glossary ………………………………………………………………………………………..<br />

Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………..<br />

iii<br />

v<br />

vi<br />

vii<br />

viii<br />

Chapter 1: Introduction …………………………………………………………………….. 1<br />

1.1 Study background ……………………………………………………………….………… 1<br />

1.2 Justification for a Process Review ………………………………………………………… 1<br />

1.3 Objectives <strong>of</strong> the Process Review …………………………………………………………. 3<br />

1.4 Study design and implementation …………………………………………………………. 4<br />

1.5 Clarifying some basic concepts ……………………………………………………………. 8<br />

Chapter 2: The Context <strong>of</strong> Literacy in Uganda …………………………………………….. 13<br />

2.1 International framework …………………………………………………………………… 13<br />

2.2 Socio-economic and education context ……………………………………………………. 16<br />

2.3 Gender context ……………………………………………………………………………… 19<br />

2.4 Policy and planning framework for adult literacy ………………………………………….. 22<br />

Chapter 3: Peoples Basic Needs Problems and Concerns ………………………………….. 27<br />

3.1 Socio-economic Characteristics <strong>of</strong> the Population …………………………………………. 27<br />

3.2 People’s perceived problems and concerns ………………………………………………… 32<br />

3.3 Views from focus group discussions on problems and needs ……………………………… 34<br />

Chapter 4: People’s Learning Desires and Readiness to Learn …………………………… 36<br />

4.1 Expressed learning desires and readiness to learn ………………………………………….. 36<br />

4.2 Expected benefits from learning ……………………………………………………………. 40<br />

4.3 Desired learning and teaching arrangements ……………………………………………….. 41<br />

4.4 Expected difficulties while learning ………………………………………………………… 42<br />

Chapter 5: Current Organisation and Management ………………………………………… 44<br />

5.1 Status <strong>of</strong> the government FAL programme ………………………………………………….. 44<br />

5.2 Other adult literacy programmes …………………………………………………………….. 49<br />

5.3 Partnership in current provision ……………………………………………………………… 54<br />

5.4 Financing <strong>of</strong> literacy programmes …………………………………………………………… 57<br />

Chapter 6: Approaches Curriculum and Materials ………………………………………….. 60<br />

6.1 Adult literacy approaches in Uganda ………………………………………………………… 60<br />

6.2 Programme contents, methods and materials ………………………………………………… 61<br />

6.3 Teaching and learning arrangements ………………………………………………………… 62<br />

6.4 Learning assessment and certification ………………………………………………………... 64<br />

Chapter 7: Participants’ Learning Experiences and Prospects for Further Learning ….… 68<br />

7.1 Learners’ characteristics and reasons for joining the literacy programme ………………..… 68<br />

7.2 Learners’ participation and learning experience …………………………………………..… 70<br />

7.3 Learners’ desire and prospects for further learning ………………………………………..… 73

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

ii<br />

Chapter 8: Literacy Instructors and their Performance ……………………………………… 76<br />

8.1 Instructors’ characteristics …………………………………………………………………….. 76<br />

8.2 Instructors’ training for literacy work ………………………………………………………… 77<br />

8.3 Instructors’ motivation and incentives ………………………………………………………… 78<br />

8.4 Instructors’ participation and performance ……………………………………………………. 79<br />

Chapter 9: Current Provision as a Response to the Learning Needs and Desires …………… 81<br />

9.1 People’s needs concerns and learning desires …………………………………………………. 81<br />

9.2 Programme achievements ……………………………………………………………………... 82<br />

9.3 Challenges and concerns in the current provision …………………………………………….. 84<br />

9.4 People’s suggestions for improvement ………………………………………………………... 89<br />

Chapter 10: Conclusions and Recommendations ……………………………………………… 91<br />

10.1 Conclusions …………………………………………………………………………………. 91<br />

10.2 Recommendations …………………………………………………………………………... 91<br />

References ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 97<br />

Annexes ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 99<br />

Annex 1: Writing the wrongs: international benchmarks on adult literacy 2005 ………………... 99<br />

Annex 2: The Abuja Call for Action 2007 ……………………………………………………….. 100<br />

Annex 3: Organisations from which information was obtained in the sampled districts ………… 103<br />

Annex 4: Other organisations reported operating in the sampled districts ……………………….. 103<br />

Annex 5: Summary <strong>of</strong> information obtained from some national organisations ………………… 105<br />

5.1 Literacy Network <strong>of</strong> Uganda (LitNet) …………………………………………………. 105<br />

5.2 Adult Literacy and Basic Education Centre (ALBEC) ………………………………… 107<br />

5.3 Literacy Aid Uganda …………………………………………………………………… 108<br />

5.4 Uganda Programme <strong>of</strong> Literacy for Transformation (UPLIFT) ……………………….. 110<br />

5.5 Young Men’s Christian Association Kampala (YMCA) ………………………………. 113<br />

Annex 6: Conditional Grants for FAL to the Districts 2006/2007 ……………………………….. 115<br />

Annex 7: Terms <strong>of</strong> reference ……………………………………………………………………... 116<br />

Annex 8: Instruments used in the Process Review ……………………………………………….. 120<br />

Annex 8.1: Interview schedule for adult literacy instructors ………………………………. 120<br />

Annex 8.2: Interview schedule for participants in adult literacy programmes ……………. 127<br />

Annex 8.3: Interview schedule for graduates <strong>of</strong> adult literacy programmes …………….… 132<br />

Annex 8.4: Interview schedule for non-literate adults (potential FAL learners) ……….….. 137<br />

Annex 8.5: Questionnaire for district leaders and <strong>of</strong>ficials ………………………………... 140<br />

Annex 8.6: Questionnaire for sub-county leaders and <strong>of</strong>ficials ……………………………. 143<br />

Annex 8.7: Questionnaire for heads <strong>of</strong> organisations and other leaders at district level …… 146<br />

Annex 8.8: Guiding questions for semi-structured interviews with community leaders and local<br />

government leaders and <strong>of</strong>ficials ……………………………………………… 149<br />

Annex 8.9: Guiding questions for semi-structured interviews with schooled people ……… 151<br />

Annex 8.10: Guide for focus group discussions used in the study …………………………. 153

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

iii<br />

List <strong>of</strong> <strong>Table</strong>s Figures Boxes and Photos<br />

TABLES<br />

Page<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 1.1 Categories <strong>of</strong> the study population 4<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 1.2 Sampled districts for the process review 5<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 1.3 Methods and instruments planned 6<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 1.4 Data collected from the different populations 7<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 2.1 Trend in literacy rates for population aged 10 years and above 1997-2002/3 17<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 3.1 Control over radio by sex 30<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 3.2 Radio listening by sex 30<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 3.3 NAPE assessment results for P3 and P6 pupils (1999 & 2003) 30<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 3.4 What government could do to solve people’s problems 33<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 3.5 Problems associated with illiteracy 34<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 4.1 Explanation why non-literates want to learn the different things 37<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 4.2 Participants’ reasons for joining the adult literacy programme 37<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 4.3 Graduates’ reasons for joining adult literacy class 38<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 4.4 Person non-literate sample prefers to teach them by sex 41<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 5.1 District and sub-county contribution to FAL 47<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 5.2 Whether FAL provision has improved since 2003 as rated by respondents at the 49<br />

district and sub-county<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 5.3 Reasons by district and sub-county respondents for assessment <strong>of</strong> existing 55<br />

collaboration<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 5.4 Government financial releases in Uganda shillings 57<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 5.5 ICEIDA financial support to FAL in Uganda 59<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 6.1 Basic education curriculum in primary school and in FAL 66<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 7.1 Reasons for learners’ absence from class according to learners and instructors 71<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 7.2 Learners’ reasons for enjoying class and instructors’ explanation <strong>of</strong> learners’ 72<br />

interest<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 7.3 What learners reported finding easy or difficult to learn 72<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 8.1 What instructors read and write 77<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 8.2 Instructors’ reasons for deciding to teach and for happiness with the work 78<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 8.3 Learners’ rating <strong>of</strong> their instructors 80<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 9.1 Problems reported by the instructors 85<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 9.2 Challenges/problems mentioned by learners 86<br />

<strong>Table</strong> 9.3 Learners’ and instructors’ suggestions for improvement 89

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

iv<br />

FIGURES<br />

Figure 3.1 Main occupation <strong>of</strong> respondents 27<br />

Figure 3.2 Instructors’ main occupation 28<br />

Figure 3.3 Source <strong>of</strong> light at night 29<br />

Figure 3.4 Have a radio in the family 29<br />

Figure 3.5 School attendance 31<br />

Figure 3.6 Levels <strong>of</strong> schooling attained by those who attended 32<br />

Figure 3.7 Non-literates’ most serious problems 32<br />

Figure 3.8 Non-literates’ plans for improvement 33<br />

Figure 4.1 Things non-literates want to learn first 36<br />

Figure 4.2 Things non-literate sample want to read 38<br />

Figure 4.3 What non-literate sample wants to write 39<br />

Figure 4.4 Number <strong>of</strong> class days per week preferred by non-literate sample 42<br />

Figure 4.5 Difficulties while learning anticipated by non-literates 43<br />

Figure 5.1 Whether FAL is a priority and regular budget item at district and sub-county 46<br />

Figure 5.2 District and sub-county respondents’ rating <strong>of</strong> current policy as an adequate 48<br />

guide for adult literacy<br />

Figure 5.3 Collaboration in adult literacy provision as rated at the district and sub-county 54<br />

Figure 7.1 Age distribution <strong>of</strong> learners 68<br />

Figure 7.2 Marital status <strong>of</strong> learners by sex 70<br />

Figure 7.3 Learners’ interest and attendance as assessed by their instructors 70<br />

Figure 8.1 How long instructors have taught literacy 79<br />

Figure 8.2 Instructors’ absence from class 80<br />

Figure 9.1 Personal problems while teaching as reported by instructors 85<br />

BOXES<br />

Box 2.1 Comparison between EFA and MDG 14<br />

Box 2.2 United Nations Literacy Decade 15<br />

Box 5.1 Multi-stakeholder partnership – Kabamwe Tukore FAL 56<br />

Box 6.1 A traditional adult literacy setting 62<br />

PHOTOS<br />

FAL instructor with participants in an active learning session in Kalangala Cover<br />

Process review team and Pr<strong>of</strong> Rogers discussing with the community in Bugiri xix<br />

Women in Bundibugyo bearing their heavy burdens with a smile 12<br />

FAL graduates in Bundibugyo proudly display their certificates 64<br />

Elderly FAL participant interviewed in Kumi 69<br />

University adult education students studying literacy practices in the field 96

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

v<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT<br />

We thank all those who contributed in various ways to this process review <strong>of</strong> the functional adult literacy<br />

programme in Uganda:<br />

- all the people who gave their time to be interviewed or took part in the focus group discussions in the<br />

selected sites <strong>of</strong> the sampled districts<br />

- the Community Development <strong>of</strong>ficers <strong>of</strong> the selected districts and sub-counties, other <strong>of</strong>ficials and<br />

other leaders who mobilised the sampled people and gave various other types <strong>of</strong> support<br />

- members <strong>of</strong> the Community Development <strong>of</strong>fice and others recruited in the districts, with whom we<br />

worked as a team to carry out the field work<br />

- the members <strong>of</strong> the core research assistant team from Kampala who participated in the production <strong>of</strong><br />

the instruments, data collection in all districts and the final editing <strong>of</strong> the data pieces before data<br />

analysis and especially the few who coded the instruments for analysis<br />

- those who participated in the workshop to discuss the draft report are highly appreciated for the<br />

significant contributions they made to help the review team improve the study and report<br />

- in particular, we thank the civil society group <strong>of</strong> participants who met after the workshop and<br />

submitted well-considered comments and suggestions that the review team has thoroughly used<br />

Very special thanks go to Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Alan Rogers for his keen interest in the task and very useful inputs<br />

that have made a big difference to the study.<br />

Finally and most importantly, we thank the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Labour, Gender and Social Development and the<br />

Icelandic International Development Agency (ICEIDA) <strong>of</strong>fice in Kampala for initiating this process<br />

review, giving us the opportunity to carry it out and providing support during the accomplishment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

task. ICEIDA is specially thanked for providing the finances for the job and the prompt provision <strong>of</strong> the<br />

funds at each stage <strong>of</strong> the exercise. We hope your contribution will bear the fruit that you expect.<br />

Process Review Team<br />

Reviewers<br />

1. Anthony Okech (Team Leader) Adult Education specialist, long experience at Makerere University<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Adult and Continuing Education, has led numerous research projects<br />

2. I.M Majanja Zaaly’embikke (Reviewer) Training and management consultant, long experience<br />

training in the Cooperative Department, the FAL programme and various NGOs<br />

3. Catherine Mugisha Rwaninka (Reviewer) Gender specialist, independent consultant, long experience<br />

training and gender mainstreaming in Cooperative Department and NGOs<br />

4. Gabriel Obbo Katandi (Reviewer) Curriculum expert working at NCDC, Kampala<br />

5. Fred Kabuye Musisi (Reviewer) Socio-economic development expert, long experience in CSO<br />

development work, currently Director Africa 2000 Network Uganda<br />

International Adviser<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Alan Rogers, an international expert in adult education and learning, with wide experience in<br />

Asia and Africa, has written numerous articles and books on adult learning and literacy and is currently<br />

visiting pr<strong>of</strong>essor at the Universities <strong>of</strong> Nottingham and East Anglia and Convenor <strong>of</strong> the Uppingham<br />

Seminars in Development.<br />

Research Assistants<br />

Angelo Ogola (Research Assistant)<br />

Ann Ruth Masai (Research Assistant)<br />

Donnah Atwagala (Research Assistant)<br />

Esther Norah Nakidde (Research Assistant)<br />

Francis Aduka (Research Assistant)<br />

Harriet Akello (Research Assistant)<br />

Jane Frances Nabasirye (Research Assistant)<br />

(60 others recruited for work in specific districts)

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

vi<br />

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS USED<br />

ACDO Assistant Community Development Officer<br />

ADRA Adventist Development and Relief Agency<br />

ALBEC Adult Literacy and Basic Education Centre<br />

ALMIS Adult Literacy Management Information System<br />

BTVET Business, Technical and Vocational Education and Training<br />

CBO Community Based Organisation<br />

CDA Community Development Assistant<br />

CDO Community Development Officer<br />

CEFORD Community Empowerment for Development<br />

CSO Civil Society Organisation<br />

DIFRA Dick Francis’s Language and Literacy Services<br />

DVV German Adult Education Association<br />

EFA Education for All<br />

EFAG Education Funding Agencies Group<br />

FAL Functional Adult Literacy<br />

FALP Functional Adult Literacy Programme<br />

FBO Faith Based Organisation<br />

FGD Focus Group Discussion<br />

GAD Gender and Development<br />

GOU Government <strong>of</strong> Uganda<br />

IALS International Adult Literacy Surveys<br />

ICEIDA Icelandic International Development Agency<br />

ICT Information and Communication Technology<br />

IGA Income Generating Activity<br />

IMF International Monetary Fund<br />

INFOBEPP Integrated Non-Formal Basic Education Pilot Project<br />

KAFIA Kalangala FAL Instructors’ Association<br />

LABE Literacy and Adult Basic Education<br />

LC Local Council<br />

LitNet Literacy Network<br />

MDG Millennium Development Goals<br />

MFPED Ministry <strong>of</strong> Finance, Planning and Economic Development<br />

MGLSD Ministry <strong>of</strong> Gender, Labour and Social Development<br />

MOES Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education and Sports<br />

MOLG Ministry <strong>of</strong> Local Government<br />

MP Member <strong>of</strong> Parliament<br />

NAADS National Agricultural Advisory Services<br />

NAPE National Assessment <strong>of</strong> Progress in Education<br />

NARO<br />

NCDC<br />

National Agricultural Research Organisation<br />

National Curriculum Development Centre<br />

NGO Non-Government Organisation<br />

NWASEA National Women’s Association for Social and Educational Advancement

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

vii<br />

OECD Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development<br />

PAF Poverty Action Fund<br />

PEAP Poverty Eradication Action Plan<br />

PEVOT Promotion <strong>of</strong> Employment-Oriented Vocational Training<br />

PMA Plan for Modernisation <strong>of</strong> Agriculture<br />

REFLECT Regenerated Freirean Literacy through Empowering Community Techniques<br />

SACCO Savings and Credit Cooperative Organisation<br />

SDIP Social Development Sector Investment Plan<br />

SOCADIDO Soroti Catholic Diocese Development Organisation<br />

SPSS Statistics Package for Social Sciences<br />

TOCIDA Tororo Community-Initiated Development Association<br />

UACE Uganda Advanced Certificate <strong>of</strong> Education<br />

UBOS Uganda Bureau <strong>of</strong> Statistics<br />

UCE Uganda Certificate <strong>of</strong> Education<br />

UDHS Uganda Demographic and Health Surveys<br />

UGAADEN Uganda Adult Education Network<br />

ULALA Uganda Literacy and Adult Learners Association<br />

UNDP United Nations Development Programme<br />

UNEB Uganda National Examinations Board<br />

UNESCO United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation<br />

UNFPA United Nations Fund for Population Activities<br />

UNICEF United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund<br />

UPE Universal Primary Education<br />

UPLIFT Uganda Programme <strong>of</strong> Literacy for Transformation<br />

UPPA Uganda Participatory Poverty Assessment<br />

WID Women in Development<br />

GLOSSARY<br />

FAL (Functional Adult Literacy) is in this report used to refer to the Government literacy programme<br />

being implemented in the districts <strong>of</strong> Uganda and the methodology it uses. There are also other<br />

organisations in Uganda that use the FAL approach.<br />

Instructor is the word used to refer to the teacher in the Government adult literacy programme. In<br />

programmes using REFLECT and in some other programmes the word facilitator is used. However,<br />

in this report, the word instructor is sometimes used to refer to teachers in adult literacy activities<br />

when the various programmes are being referred to together.<br />

Graduate is used to refer to those participants who sat and passed the pr<strong>of</strong>iciency test in the FAL<br />

programme. Some <strong>of</strong> those interviewed had completed more than one level <strong>of</strong> the programme.<br />

Non-literate refers to those sampled community members who have never attended adult literacy classes.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the sample cannot read and write but there were many who can, although they are also<br />

referred to as non-literate. Sometimes the sample is referred to as potential learners.

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

viii<br />

Executive Summary<br />

0.1 The Assignment<br />

During the 2006/2007 financial year, the last covered under the National Adult Literacy Strategic<br />

Investment Plan (NALSIP) (2002/3-2006/7), the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Gender, Labour and Social Development<br />

(MGLSD), which is in charge <strong>of</strong> adult literacy in Uganda, found it important to undertake a process<br />

review <strong>of</strong> its functional adult literacy programme (FAL) in readiness for the preparation <strong>of</strong> a new plan.<br />

For that reason the review covered that period covered by NALSIP. The Icelandic International<br />

Development Association (ICEIDA) accepted to support the review. An independent consultant was<br />

commissioned to undertake the review with his own team but selected according to specifications in the<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> reference. MGLSD and ICEIDA recruited also Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Alan Rogers, internationally renowned<br />

and widely published in Adult Learning and Literacy to enable the process review to take into account<br />

international dimensions and changing concepts <strong>of</strong> ‘literacy’.<br />

The general objective <strong>of</strong> the process review was to assess the changing needs for FAL and review the<br />

current FAL programme and its context so as to provide information required for its further development,<br />

refinement and improvement to adequately address the current needs. Specifically the review was to:<br />

1. Identify and describe the basic needs, problems and concerns <strong>of</strong> the FAL participants and<br />

potential participants<br />

2. Assess the learning needs and desires <strong>of</strong> the target population<br />

3. Determine the status and performance <strong>of</strong> the Government FAL and other adult literacy<br />

programmes in the country<br />

4. Analyze the values attained by learners through the formal basic education curriculum and<br />

propose how the same values can be attained through the non-formal Curriculum i.e. adapted to<br />

suit the needs <strong>of</strong> adult learners with the view to obtaining equivalent qualifications.<br />

5. Draw lessons from past and current literacy programmes for planning the FAL programme and<br />

make recommendations for<br />

• redesigning the programme to meet the changing and unmet needs<br />

• issues to be included in the adult learning policy that is currently under development<br />

• the further development <strong>of</strong> the adult learning qualifications framework.<br />

• identify the current incentive arrangement and advise on the best option/modality.<br />

As the above objectives drawn from the terms <strong>of</strong> reference show, the focus <strong>of</strong> the process review was the<br />

government FAL programme. The purpose was to study its current performance as an adequate response<br />

to the current needs, which had, therefore, also to be identified and analysed. The needs assessment and<br />

performance review are therefore closely linked. However, the government FAL programme is not alone<br />

in providing literacy education in Uganda. The several non-government providers <strong>of</strong> literacy education in<br />

Uganda could be meeting needs that the government may not be meeting adequately. That is why<br />

objective number three addresses not only the government FAL but also other adult literacy programmes<br />

in the country.<br />

0.2 Methodology<br />

The process review used a mix <strong>of</strong> methods and instruments to obtain both qualitative and quantitative<br />

data: analysis <strong>of</strong> programme documents, structured and semi-structured interviews, self-completed

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

ix<br />

questionnaires, focus group discussions and observation. 17 districts were sampled from all regions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

country and data were collected from a total <strong>of</strong> 1300 respondents composed <strong>of</strong>: FAL participants,<br />

graduates and instructors, a sample <strong>of</strong> non-literates, district leaders and <strong>of</strong>ficials, sub-county leaders and<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials, heads <strong>of</strong> organisations at district level, schooled people and local leaders. In addition several<br />

hundred more respondents were covered through focus group discussions from most <strong>of</strong> the same<br />

populations. The data collected were analysed both for quantitative information using the SPSS computerbased<br />

programme for frequencies and percentages, and qualitatively to bring out the trends and patterns in<br />

the focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews.<br />

Some papers on changing understandings <strong>of</strong> literacy and on different practices <strong>of</strong> developing adult<br />

literacy learning programmes in other contexts were utilised. These were mainly contributed by Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

Alan Rogers, who was also able to visit the districts <strong>of</strong> Kalangala and Mukono, which were not in the<br />

sample and from which he obtained valuable information that was used in this study, including that he<br />

captured in the photo on the cover page <strong>of</strong> this report.<br />

MIGLSD and ICEIDA convened a two-day workshop bringing together a cross-section <strong>of</strong> stakeholders<br />

from all over the country to discuss a first draft <strong>of</strong> the report. The contributions <strong>of</strong> the workshop<br />

participants enabled the process review team to fill in information gaps and enrich the report through<br />

more reflection on the issues raised and the suggestions given. A second workshop organised mainly by<br />

CSOs made other useful contributions that were used to further enrich the report.<br />

0.3 Main Findings<br />

The research team is confident that, although some <strong>of</strong> the responses will undoubtedly have been given to<br />

please the interviewers, the views expressed here are substantially those <strong>of</strong> the respondents.<br />

0.3.1 People’s basic needs, problems and concerns<br />

Poverty, mentioned by about 65% <strong>of</strong> the male “non-literate” respondents and 51% <strong>of</strong> the female, or lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> money, mentioned by 35% male and 56% female are the main problems and the top concerns <strong>of</strong> the<br />

predominantly rural population, depending on subsistence agriculture. This is followed by disease or<br />

illness (41% male and 44% female). Most <strong>of</strong> the non-literate respondents would like to change this<br />

situation by improving agricultural production (41%); but others by doing business (13%) and incomegenerating<br />

activities (10%). They would like to see government helping them to improve by providing<br />

micro-finance and supporting agriculture, but also by providing adult education and supporting FAL<br />

programmes financially.<br />

The non-literate respondents are also concerned about illiteracy (19% male and 19% female) and lack <strong>of</strong><br />

knowledge and skills (9% female and 11% male), although these are not among the top concerns. They<br />

articulate clearly the problems associated with illiteracy and the benefits they expect from becoming<br />

literate.<br />

0.3.2 People’s learning desires and readiness to learn<br />

Literacy takes top priority among the things the people would like to learn first, whereas illiteracy ranked<br />

fourth in the list <strong>of</strong> most serious problems, and acquisition <strong>of</strong> literacy skills was not among their<br />

spontaneous strategies for dealing with the problems.<br />

They want to learn also numeracy, technical and vocational skills, agriculture, languages, health and<br />

religion, in that order <strong>of</strong> frequency <strong>of</strong> mention. The fact that agriculture and technical and vocational<br />

training also feature somewhat significantly would seem to indicate that the people to some extent see the

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

x<br />

acquisition <strong>of</strong> knowledge and skills as having a contribution to make to improvements in their strategies<br />

to deal with poverty, their most serious problem.<br />

The people explained that they want to learn these different things in order to: read and write on their<br />

own; sustain their life; get information easily; be able to carry out a project; gain confidence and keep<br />

secrets. They felt that being literate would, specifically, be very useful in daily life; enable them to do<br />

things by themselves; make for easy communication; take them out <strong>of</strong> ignorance and change their life and<br />

bring about development.<br />

More than half the current literacy programme participants and literacy graduates want to learn English.<br />

Some want to learn more reading, writing and numeracy and general knowledge. Only few <strong>of</strong> both the<br />

participants and graduates mentioned agriculture and business and even fewer mentioned technical and<br />

vocational training. Health was also mentioned, but by fewer than 10%.<br />

Apparently, the change brought about by participation in the literacy programme has been to strengthen<br />

even further the orientation <strong>of</strong> the learning desires towards things to do with communication and social<br />

benefits and weaken the desire for learning related to livelihood knowledge and skills.<br />

0.3.3 Status and performance <strong>of</strong> adult literacy programmes<br />

a) Governance, organisation and management<br />

MGLSD is responsible for adult literacy in the country and currently manages adult literacy as a set <strong>of</strong><br />

activities with a coordinator reporting to the Commissioner, Department <strong>of</strong> Elderly and Disability. The<br />

coordinator works with a principal literacy <strong>of</strong>ficer and two senior literacy <strong>of</strong>ficers. Adult literacy and<br />

adult education in general does not have a directorate, department or any formal unit.<br />

Although in the 1992 White Paper on Education government stated that it had recognised adult and nonformal<br />

education as very important and decided to place it in the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education and Sports, with a<br />

Directorate, MGLSD argues that it is the right home for adult and non-formal education since it deals<br />

with vulnerable groups, non – literates inclusive. This is the current Government position.<br />

The current location and status <strong>of</strong> FAL deprives it <strong>of</strong> the benefit <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional specialisation since it is<br />

just another set <strong>of</strong> activities that is managed by any other civil servant. However, the Ministry is taking<br />

measures to uplift the status so that it becomes more visible in the Ministry structure. Pr<strong>of</strong>essionalism in<br />

this area is also being emphasised.<br />

The FAL programme is implemented by the local governments in the decentralised system by the<br />

Community Development Officer (CDO) usually in the District Community Based Services Department<br />

or Directorate, which is in charge <strong>of</strong> FAL, among other programmes. The process review found that the<br />

relations and linkages between MGLSD and the implementation mechanism in the districts are not clear<br />

and are rather weak. The relevant Minister <strong>of</strong> State explained the efforts that he personally and the<br />

ministry were taking to rectify this situation.<br />

There are strikingly wide variations among the districts and sub-counties in the level <strong>of</strong> commitment to<br />

FAL, as manifested through budgeting, actual financing and implementation. Whereas decentralisation<br />

gives a large degree <strong>of</strong> autonomy, the central government has still the role <strong>of</strong> ensuring pursuit <strong>of</strong> national<br />

goals and quality in the provision <strong>of</strong> government financed services. The mechanism for this in the<br />

provision <strong>of</strong> FAL is very inadequate.

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

xi<br />

Actual implementation <strong>of</strong> FAL is at the sub-county level. FAL currently operates in all districts but in<br />

only 740 out <strong>of</strong> the 966 sub-counties. There seems to be inadequate support for the sub-counties from the<br />

district level as explained below, thus weakening the actual implementation in the communities.<br />

The districts and sub-counties state that FAL is a priority in their respective Councils to some extent a<br />

regular item in their budgets. However, the budget allocations are in most cases just nominal and the<br />

actual availability <strong>of</strong> the funds is not assured. The districts and sub-counties pointed out other forms <strong>of</strong><br />

contribution to the programme: sensitisation, mobilisation, provision <strong>of</strong> leaning centres and similar inkind<br />

contribution by both the councils and the communities.<br />

The government encourages partnership with civil society organisations and other agencies, national and<br />

international in the provision <strong>of</strong> adult literacy. This has enabled many other organisations to become<br />

involved in the provision <strong>of</strong> adult literacy. Civil society organisations (CSOs) are contributing<br />

significantly, through policy advocacy, dissemination <strong>of</strong> innovative approaches and ideas, and actual<br />

implementation <strong>of</strong> literacy education on a small-scale basis. However, there has been concern that there is<br />

inadequate mechanism for more fruitful collaboration, in spite <strong>of</strong> some guidelines in the MGLSD<br />

documents, developed in consultation with CSOs. The fact that the guidelines are optional to other<br />

providers is in harmony with the liberal environment <strong>of</strong> Uganda. However, MGLSD does not reach out<br />

enough to dialogue with CSOs, which results in little use <strong>of</strong> the guidelines by other providers.<br />

Partnership with agencies like UNESCO, UNICEF, and DVV International in the past contributed<br />

significantly to the development <strong>of</strong> FAL. Currently, the most significant such partner is the Icelandic<br />

International Development Agency (ICEIDA), which, apart from sustained support <strong>of</strong> programmes on the<br />

Lake Victoria islands, is also supporting national FAL efforts such as developing the national adult<br />

literacy management information system (NALMIS) and the non-formal adult learning qualifications<br />

framework.<br />

The leaders and <strong>of</strong>ficials at district and sub-county level on the whole feel that the current policy is a good<br />

guide for the implementation <strong>of</strong> FAL. However, concerned civil society organisations at national level<br />

find the current policy framework inadequate and have been working with MGLSD to put in place a new<br />

one. The main organisations involved are Uganda Adult Education Network (UGAADEN), Literacy<br />

Network for Uganda (LitNet) and Uganda Literacy and Adult Learners Association (ULALA).<br />

b) Financing and other non-human resources<br />

FAL is funded mainly through the government Poverty Action Fund (PAF) with a budget release <strong>of</strong><br />

slightly above shillings 3 billion per year, shared almost equally between MGLSD headquarters and the<br />

districts. However, it has also benefited from project funding from bilateral and international partners<br />

through the partnerships mentioned above.<br />

The funding is very inadequate. With the current number <strong>of</strong> districts at 80, and shillings 1.64 billion as the<br />

total annual release to the districts, the average annual release per district is shillings 20,000,000/=, about<br />

5,000,000/= (about US $ 2,900) per quarter or about 1,670,000/= (US $ 966) per month. The districts<br />

have no other revenue base to meaningfully supplement this budget.<br />

From this meagre budget, the district is expected to provide also for the learning venue, equipment and<br />

instructional materials. Some <strong>of</strong> these requirements are provided in kind by the local governments and the<br />

communities, but generally there is serious lack <strong>of</strong> facilities with most classes taking place under trees<br />

without furniture for the instructor and learners. Most classes have a blackboard but many <strong>of</strong>ten lack<br />

chalk.

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

xii<br />

The finances released for FAL from the central government hardly reach the sub-county and the<br />

communities where the actual implementation takes place. As a result the sub-county community workers<br />

have no resources to supervise and monitor the programme and the sub-county cannot support the class<br />

centres in any way. It is necessary to have strong mechanisms and systems for tracking the releases,<br />

expenditures and impact (value for money). Some CSOs (UGAADEN and LitNet) have started a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> initiatives towards budget tracking for basic Education, which can be used, supported and adapted as<br />

models upon which improvements can be made.<br />

MGLSD needs to explore ways <strong>of</strong> widening funding opportunities for FAL available in Uganda such as<br />

marketing it to Education Funding Agencies Group and Education For All funding initiatives such as<br />

Education Fast Track Initiative.<br />

c) Approaches, curriculum and materials<br />

As recommended after the pilot phase in 1995, the programme at first spread gradually, moving out into<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> the country where interest was explicit and demands for the programme were made. While the<br />

principle <strong>of</strong> gradual expansion has been maintained, the political push from members <strong>of</strong> Parliament and<br />

local politicians is to have the programme spread in every part <strong>of</strong> the country, resulting in some token<br />

implementation in parts <strong>of</strong> all the districts<br />

Functional adult literacy, an approach that is designed to impart reading and writing skills side by side<br />

with other functional knowledge in agriculture, health and other areas, is the most commonly used in<br />

Uganda. Just over a decade ago, Action Aid introduced the REFLECT approach to Uganda and it has<br />

been adopted by a number <strong>of</strong> non-governmental providers. Government provision has also taken up<br />

REFLECT in some cases.<br />

The curriculum prepared for the pilot project in 1992 has been only slightly modified in subsequent<br />

revisions and still guides the implementation <strong>of</strong> the government programme, which hence tends to be a<br />

“one-size fits all” approach, although efforts are made to diversify through development and use <strong>of</strong><br />

primers and teachers’ guides relevant to the different parts <strong>of</strong> the country. The FAL approach also<br />

encourages flexibility in the actual learning situation but the inadequately trained instructors seek safety<br />

in closely sticking to the curriculum and materials.<br />

Learners and graduates, however, expressed great satisfaction with what they had learnt and explained<br />

how they had benefited from it and how it was continuing to help them in their daily life and their<br />

improvement efforts. They also wanted to learn more, especially English and more reading, writing and<br />

numeracy, but also technical and vocational training, agriculture and health.<br />

There seems to be general agreement among the programme providers that the primer and teachers’ guide<br />

prepared by the government and used by a number <strong>of</strong> other providers as well is a useful starting point.<br />

However, optimal use <strong>of</strong> these materials is only possible if the instructors are adequately trained, which is<br />

not the case in Uganda today. Some CSOs find the government prepared materials inappropriate and have<br />

developed their own materials.<br />

d) Learners and their participation<br />

The majority <strong>of</strong> adult literacy learners in Uganda are female. The learner sample for the process review<br />

consisted <strong>of</strong> 79% female and 21% male. By very interesting coincidence, this was exactly the same ratio<br />

in the learner sample <strong>of</strong> the 1999 evaluation <strong>of</strong> adult literacy in Uganda! This is <strong>of</strong>-course a much higher<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> women than the proportion <strong>of</strong> women who are non-literate, compared to the men. It is<br />

obvious that there are many men who would be expected to need the literacy programme but are not

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

xiii<br />

participating. This has been a matter <strong>of</strong> concern to the government and other literacy providers and to the<br />

Uganda Literacy and Adult Learners Association (ULALA). There is need for a special investigation <strong>of</strong><br />

this situation.<br />

There were rather few learners in the sample aged 20 or younger. Between the ages <strong>of</strong> 20 to 50 years,<br />

participation was almost even, decreasing only slightly. The percentage <strong>of</strong> non-literates in Uganda<br />

increases with age, but there is not a corresponding increase in participation.<br />

The majority who participate in FAL have attended school. In this sample 57% had attended school (71%<br />

<strong>of</strong> the men and 54% <strong>of</strong> the women). Of those who had attended school, the majority had gone only up to<br />

Primary 4, a level at which literacy acquisition is still very low, as revealed by the 1999 evaluation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

adult literacy programme in Uganda and the National Assessment <strong>of</strong> Progress in Education (NAPE) by<br />

the Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB).<br />

According to the instructors’ assessment, female learners are much more interested in learning, and attend<br />

more regularly than men. On their part, 97.5% <strong>of</strong> the learners reported that they enjoy learning and 52.6%<br />

said they always attend. This is somewhat higher than the instructors’ assessment <strong>of</strong> learners’ attendance.<br />

It was not possible to calculate the drop out or withdrawal rate due to inadequate statistics.<br />

Sickness, funerals, domestic work and social commitments appear prominently among the reasons for<br />

being absent from class. Farm work and business feature less prominently.<br />

e) Instructors and their performance<br />

The majority <strong>of</strong> instructors have had some secondary school education although only a few have<br />

completed, obtained the school certificate <strong>of</strong> education or gone higher. This poses a challenge for<br />

enhancing the programme and introducing further education for those adults who want to continue.<br />

The majority <strong>of</strong> the instructors have been trained for adult literacy work, but most <strong>of</strong> them for only up to 5<br />

days, without any refresher training for many years. This is mainly because <strong>of</strong> inadequate funding<br />

reaching the district level where the training <strong>of</strong> instructors takes place. Some good capacity has been<br />

developed at the level <strong>of</strong> trainers and trainers <strong>of</strong> trainers, although there is still need for more.<br />

Over 80% <strong>of</strong> the instructors do some reading and writing that is not part <strong>of</strong> their teaching. They read<br />

books <strong>of</strong> various types and newspapers. They write mainly letters and personal records. In this, instructors<br />

are a good example to their learners.<br />

41% <strong>of</strong> the instructors reported receiving some form <strong>of</strong> incentive: 64% <strong>of</strong> them in cash; 26% bicycles;<br />

and 15% T-shirts. However, the cash incentives from government that many <strong>of</strong> them receive is extremely<br />

small in many districts, coming to as little as shillings 5,000/= (= US $ 2.50) every 3 months, but <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

shillings15,000/= every 3 months. In most districts, as the findings show, even this little is not paid at all.<br />

Most instructors are happy and some even very happy with their work, despite the fact that they receive<br />

very small incentives. They say they are happy to fight illiteracy and promote development and are happy<br />

<strong>of</strong> their achievements.<br />

There seems to be a significant amount <strong>of</strong> perseverance among the instructors: almost 40% had taught for<br />

over 3 years and only 27% had taught for one year or less. This is in contrast with some programme<br />

managers’ concerns that there is a high turn-over among instructors.

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

xiv<br />

The commitment is also manifested by the regularity <strong>of</strong> their attendance to their class duties. To crosscheck<br />

this, learners were asked to rate their instructor’s attendance. The rating given by learners is much<br />

more positive than that given by the instructors themselves!<br />

0.3.4 Signals from International Developments<br />

Since 1992 when FAL was launched, there have been two major developments which are particularly<br />

relevant to this process review <strong>of</strong> FAL:<br />

a) a move from talking about adult education to talking about adult learning: an interest in informal<br />

learning (the experiential learning which goes on outside <strong>of</strong> the classroom) which is seen as<br />

participation in a community <strong>of</strong> practice<br />

b) a change <strong>of</strong> understanding <strong>of</strong> literacy and numeracy, especially the concept <strong>of</strong> the pluralities <strong>of</strong><br />

literacy (embedded literacy).<br />

As a result, new practices have sprung up, among these are the following:<br />

• The UNESCO Global Monitoring Report on Literacy in 2005 with its emphasis on the literacy<br />

environment<br />

• A move away from a campaign model towards a slow progression in adult literacy (like an extension<br />

service for literacy) (e.g. Tanzania and Brazil)<br />

• Work-based literacy (Botswana) and skill training-based literacy (Afghanistan)<br />

• Community literacy programme (Nepal) with user groups<br />

• Drop-in centres <strong>of</strong> adults (Nigeria)<br />

• ‘Home-school’ links in numeracy and literacy (e.g. family literacy in S Africa and Uganda; building<br />

bridges between literacy class and the community in India)<br />

0.3.5 Key Concerns Identified<br />

Arising from the findings <strong>of</strong> this study and the international comparisons, a number <strong>of</strong> key concerns for<br />

FAL have been identified:<br />

• Relevance <strong>of</strong> the curriculum to the diverse needs and the poverty eradication efforts<br />

• Encouragement <strong>of</strong> the uses <strong>of</strong> literacy and numeracy in the daily lives <strong>of</strong> the participants for<br />

development purposes<br />

• Instructor training and incentives<br />

• Unreached populations, including people with disabilities, the men and others with special learning<br />

needs<br />

• Status <strong>of</strong> the programme in the managing ministry and pr<strong>of</strong>essionalism in its execution<br />

• Resource availability and its distribution and proper use<br />

• Supervision, monitoring and documentation<br />

• Collaboration among government agencies and with non-government organisations<br />

0.4 Recommendations<br />

0.4.1 Redesigning the programme to meet the changing and unmet needs<br />

Under this objective the process review team recommends three routes to strengthen and widen<br />

FAL:<br />

i) Deepening FAL that is strengthening FAL relevance, management and so its effectiveness in meeting<br />

the changing needs and addressing poverty (Recommendations R1 –R6)

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

xv<br />

ii) Diversifying FAL that is widening it by turning FAL from being a single programme to being a field<br />

<strong>of</strong> activity in which different delivery systems can be found to help adults to develop their literacy<br />

skills and practices in the many different contexts in which they live (Recommendation R7)<br />

iii) Moving beyond FAL by designing provisions that take the FAL participants who so wish for<br />

continued learning beyond the current levels <strong>of</strong> FAL (Recommendation R8)<br />

R1. Revise FAL curriculum and materials for more relevance to learners’ needs and the poverty<br />

eradication efforts<br />

a) to address poverty more effectively by enabling participants to analyse its causes, identify<br />

alternatives for addressing it and take appropriate measures to overcome it<br />

b) to develop a closer link, both in design and practice, between adult learning and the country’s<br />

various poverty eradication efforts as expressed in policies and strategies such as the PEAP and<br />

PMA<br />

c) to include the other learning areas learners and graduates desire such as English, Vocational<br />

and Technical training, Agriculture, Health (including HIV/AIDS) and Business<br />

R2. Develop links between literacy learning and practice so as to promote beneficial literacy use<br />

in the home and community and at work by<br />

a) encouraging the use <strong>of</strong> literacy skills in the home and community and the influence <strong>of</strong> the home<br />

and community in the literacy learning situation, building, for example, on the experience <strong>of</strong><br />

the family literacy programme that was run by LABE in Bugiri for some years<br />

b) working to integrate FAL into skills training such as those that have been piloted in Kalangala<br />

with ICEIDA support, by the Promotion <strong>of</strong> Employment-Oriented Vocational Training<br />

(PEVOT) <strong>of</strong> MOES in Luweero, Kabale and Mubende districts, as well as by other<br />

organisations<br />

c) including in the learning situation material drawn from the daily lives <strong>of</strong> the participants to<br />

increase the uses <strong>of</strong> literacy outside <strong>of</strong> the classroom<br />

d) enhancing the literate environment by providing for mobile village libraries that could be linked<br />

to the local council (LC) systems and in other ways e.g. working with newspapers to include<br />

easy reading sections<br />

R3. Build more effective instructors who are more appropriately trained, remunerated and<br />

motivated by<br />

a) continued use <strong>of</strong> community members with an adequate educational base, at least some or<br />

complete secondary education, with adequate specific face-to-face training <strong>of</strong> at least 4 weeks,<br />

not necessarily continuous, supplemented by distance learning and leading to some recognised<br />

certificate, as is, for example, being done in Kalangala; and regular on-going support for all<br />

instructors<br />

b) strengthening the training so that the instructors build home-class links (family literacy) and<br />

develop more active group learning methods (building communities <strong>of</strong> practice)<br />

c) engaging existing adult education training institutions and organisations in developing relevant<br />

and diversified training curricula to develop the trainers and instructors able to meet the<br />

diversified learning needs <strong>of</strong> adults<br />

R4. Strengthen the management and capacity <strong>of</strong> FAL for greater effectiveness, specifically<br />

a) strengthen further the FAL management structure in the ministry<br />

b) increase funding and other resources for it: especially teaching-learning materials; use <strong>of</strong> ‘real<br />

materials’ in classes and engage the civil society in ensuring and tracking proper resource<br />

utilisation<br />

c) increase training and support for management staff, especially CDOs, particularly in<br />

monitoring and developing new ways <strong>of</strong> working

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

xvi<br />

d) develop further and ensure effective functioning <strong>of</strong> the MIS for adult literacy and basic<br />

education being created within the Ministry<br />

e) enhance the training <strong>of</strong> trainers and development <strong>of</strong> a national resource centre for adult literacy<br />

concentrating on training, research and development – perhaps developing further the centre in<br />

MGLSD, in Makerere University or one <strong>of</strong> the other relevant tertiary institutions<br />

f) restructure the FAL programme for systematic coverage focusing on specified areas <strong>of</strong> each<br />

district to ensure meaningful results in view <strong>of</strong> the limited resources available, and then<br />

gradually spreading out to other areas as more resources become available.<br />

g) strengthen the international links <strong>of</strong> FALP to keep in touch with new developments in the field<br />

in bodies such as UNESCO, ICAE and other agencies<br />

R5. Widen the financing and strengthen the financial management to ensure that adequate<br />

resources are availed for the programme, specifically:<br />

a) lobby to increase government budget allocation for FAL and other resources for the<br />

programme, especially teaching-learning materials<br />

b) work with interested international partners, e.g. Irish Aid, to find ways <strong>of</strong> tapping into<br />

funding opportunities available in Uganda such as marketing FAL to Education Funding<br />

Agencies Group and Education For All funding initiatives such as Education Fast Track<br />

Initiative<br />

c) improve financial record keeping and accountability and engage the civil society (including<br />

learners) in ensuring and tracking proper resource utilisation<br />

R6. Implement the collaboration arrangements found in the various strategy documents and<br />

guidelines to enrich adult learning provision and widen its reach, in particular:<br />

a) Activate inter-ministerial coordination and collaboration as provided for in the PEAP, NALSIP<br />

and other government documents<br />

b) Government and CSOs should work together to develop mechanisms for making real the<br />

suggestion in PEAP for subletting some literacy activities to CSOs<br />

c) Government should recognize the various roles CSOs can play and put in place measures to<br />

support CSOs to grow and take greater responsibility in the promotion <strong>of</strong> adult learning<br />

d) Government should study the initiatives that CSOs have taken and work to adopt them to enrich<br />

and widen adult learning provision; such initiatives include the innovative programmes,<br />

attractive materials and management mechanisms such as the systems for tracking the<br />

budgetary releases, expenditures and impact (value for money) that have been developed by<br />

UGAADEN and LitNet)<br />

e) CSOs should maintain and increase their momentum in advocating for adult learning<br />

opportunities and advising and providing experimental evidence on useful alternatives for best<br />

practices<br />

R7. Develop strategies and new strands <strong>of</strong> activities in FAL to reach the unreached, to include:<br />

a) strengthening the efforts to develop special packages for people with disabilities<br />

b) encouraging the inclusion <strong>of</strong> relevant literacy into skill training <strong>of</strong>fered by other agencies such<br />

as extension services and private training providers<br />

c) provision <strong>of</strong> relevant literacy and numeracy learning to existing user groups such as work-based<br />

literacy (employers), self-help and micro-credit groups etc<br />

d) development <strong>of</strong> ‘drop-in centres’ <strong>of</strong> adults to learn literacy at a time when they need it<br />

including the uses <strong>of</strong> ICT<br />

e) designing special courses, with narrow practical goals closely tied to the needs and interests <strong>of</strong><br />

the men and even combine some literacy elements into these courses (As recommended for<br />

Kalangala by Arnason and Mabuya, 2005)

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

xvii<br />

f) liaising with employers in appropriate situations to enhance the literacy practices <strong>of</strong> their<br />

employees e.g. in factories such as Tororo Cement<br />

g) using the media for programme information dissemination and to supplement the face-to-face<br />

learning is recommended to enhance the programme, since the need for more sensitisation was<br />

expressed by many<br />

R8. Design continued learning provisions for FAL participants and graduates by<br />

a) Recognising the diversity <strong>of</strong> reasons why adults in Uganda join adult literacy programmes and<br />

the need to draw out diverse continued learning programmes to satisfy the different reasons for<br />

coming to learn<br />

b) Ensuring that whatever the design <strong>of</strong> the continued learning programmes, it allows adults room<br />

for flexible self-directed learning and does not subject them to a school-type curriculum and<br />

learning routine<br />

c) Developing demand-driven programmes such as English and Small Business Courses as<br />

already being tried out in Kalangala with ICEIDA support<br />

d) Choosing and developing an appropriate approach to enable adult learners to acquire the<br />

desired accreditation and certification (See discussion in Chapter 6, Section 6.4 and R11 below)<br />

0.4.2 Issues to be included in the adult learning policy that is currently under development<br />

R9. The adult learning policy under development should include provisions to enhance the status<br />

<strong>of</strong> adult learning, its more effective and efficient management, greater commitment to it at all<br />

levels and partnership to ensure optimal use <strong>of</strong> available capacity and recourses, specifically:<br />

a) Adult learning policy must provide for an adequate adult education organisational and<br />

management structure such as what had been proposed in the 1992 White Paper on Education,<br />

without necessarily transferring the structure to the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education and Sports<br />

b) The policy must lead to, and be accompanied by, the immediate adoption <strong>of</strong> regulations and<br />

mechanisms for the promotion, coordination, supervision, monitoring and evaluation <strong>of</strong> literacy<br />

programmes in the country, at the central, district and sub-county levels.<br />

c) Specifically, measures must be put in place to ensure serious commitment to provision <strong>of</strong> adult<br />

learning opportunities in all districts and sub-counties through both dialogue and clear<br />

instructions<br />

d) Measures should also be put in place to ensure active inter-ministerial coordination and<br />

collaboration with relevant government ministries, e.g. those <strong>of</strong> Education, Health, Agriculture,<br />

Trade and Industry and Finance, Planning and Economic Development<br />

e) The policy should create a conducive environment and spell out clear mechanisms for<br />

partnership with civil society organisations, recognising that government has the primary<br />

responsibility for both policy and implementation and that civil society organisations must<br />

maintain their autonomy, but that the government has also the responsibility to support them to<br />

grow and take on responsibility for some elements in a vibrant adult learning programme<br />

R10. The adult learning policy must also lay down a strong resource base for FAL and other adult<br />

learning programme, specifically<br />

a) The policy must enable adult basic education to access budgetary allocation at a level <strong>of</strong><br />

priority similar to that enjoyed by basic education in the formal education system<br />

b) The policy should put in place strategies for involving the private sector in financing and<br />

providing other support for adult literacy programmes

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

xviii<br />

0.4.3 The further development <strong>of</strong> the adult learning qualifications framework<br />

R11. Opportunities must be opened for adults to move further from FAL and other basic<br />

education programmes in a manner that ensures diversity, flexibility and self-directed<br />

learning while at the same time enabling those who so desire to obtain formal accreditation,<br />

taking into consideration the following possible avenues:<br />

a) Enhancing the opportunities to enable people to use their literacy in their daily lives by<br />

bringing the daily lives into the classroom, building the literacy environment and encouraging<br />

individuals and groups to invest in activities that develop the literary environment<br />

b) Developing collaboration between FAL and skills training programmes to link adult literacy<br />

to skills training and skills training to literacy and enable FAL graduates who so wish to<br />

move into further skills training programmes, such as the Kalangala Small Business Course<br />

c) Developing a suitable arrangement to enable FAL graduates to obtain desired formal<br />

accreditation and equivalency, choosing from:<br />

i) Enabling adults to sit existing examinations without going through the formal school system;<br />

ii) Developing an adult education programme with its own set <strong>of</strong> examinations equivalent to<br />

those <strong>of</strong> the formal system; or<br />

iii) Developing an adult education programme with its own set <strong>of</strong> examinations different from<br />

those <strong>of</strong> the formal system but leading to recognised qualification<br />

The final choice can be a mix <strong>of</strong> two or all three alternatives.<br />

R12. The development <strong>of</strong> further learning opportunities for adults and an adult learning<br />

qualifications framework should be done in close consultation with other relevant bodies,<br />

specifically:<br />

a) Develop links with the Business, Technical and Vocational Education and Training (BTVET)<br />

Department in the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education and Sports, which is developing a qualifications<br />

framework, so as to promote linkage between the adult learning qualifications framework and<br />

the BTVET qualifications framework<br />

b) Make systematic consultations with existing curriculum and accreditation authorities to<br />

establish beneficial links in the further development <strong>of</strong> the adult learning qualifications<br />

framework<br />

0.4.4 Best incentive arrangement options for instructors<br />

R13. Incentive arrangements for instructors must be significantly enhanced and include not only<br />

material remuneration but also provision <strong>of</strong> opportunities for pr<strong>of</strong>itable collaboration<br />

among themselves, further education according to their desires and upward career<br />

movement, specifically:<br />

a) The current arrangement <strong>of</strong> giving a bicycle to each instructor should be implemented more<br />

effectively to make sure each instructor receives one: it enables them to move to the class<br />

centres, apart from helping them at home and in their other work. The arrangement should,<br />

however, include some kind <strong>of</strong> bonding so that an instructor who receives a bicycle is bound<br />

to serve for a defined period; at least two years are recommended<br />

b) Whoever is engaged as instructor should be given some incentive <strong>of</strong> a type acceptable to the<br />

instructors and affordable to the country. Ideally, the arrangement should have a regular<br />

monthly payment <strong>of</strong> allowances as recommended by many <strong>of</strong> the respondents.

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006<br />

xix<br />

c) Instructors should be encouraged to form associations, which could be supported to undertake<br />

some developmental projects and be an example in the communities where they are. The<br />

example <strong>of</strong> the ICEIDA supported association in Kalangala could provide a model.<br />

d) Instructors should be supported in their search for further education and a career path, as is<br />

being done, with ICEIDA support, in Kalangala: this could be a strong incentive.<br />

0.4.5 Way forward in the short run<br />

R14. To take forward the lessons learnt and recommendations coming out <strong>of</strong> this process review,<br />

it is recommended that MGLSD works with CSOs to set up and finance task forces or<br />

teams to draw up plans and develop curricula for a more relevant and effective adult<br />

learning provision to meet the changing needs and poverty eradication effort, specifically:<br />

a) Planning task force to develop NALSIP II and take forward the Policy and Qualifications<br />

Framework<br />

b) Technical team to revise the curriculum and training packages<br />

c) A research development task force to plan and design research and documentation <strong>of</strong> various<br />

key aspects where information is required, especially:<br />

i) Gender concerns in FAL<br />

ii) Learning session (classroom) methodology and delivery/learning techniques<br />

iii) Comprehensive survey and documentation <strong>of</strong> adult literacy provision in Uganda<br />

iv) Social uses <strong>of</strong> literacy and literacy practices in Uganda<br />

Some members <strong>of</strong> the process review team, with Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Alan Rogers, holding a discussion<br />

with FAL participants and instructors and some community members at Nabukalu Sub-County<br />

head-quarters, Bugiri District

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006 1<br />

Chapter 1: Introduction<br />

1.1 Study background<br />

Uganda considers education one <strong>of</strong> the most important strategies in poverty eradication, which is the basis<br />

<strong>of</strong> its planning today. The country has seriously embarked on the implementation <strong>of</strong> education for all, in<br />

which the government plays a major role through formal education for children and youth and functional<br />

adult literacy (FAL) for youth and adults. Whereas the main government focus has been on universal<br />

primary education, attention has also been given to the other aspects <strong>of</strong> education including FAL, whose<br />

recent development can be summarized as follows:<br />

a) Re-launch <strong>of</strong> the government’s functional adult literacy provision in 1992 through the Integrated Non-<br />

Formal Basic Education Pilot Project (INFOBEPP) in eight districts representing the four regions <strong>of</strong><br />

Uganda, preceded by a country-wide needs assessment survey as a basis for the project<br />

b) Process review <strong>of</strong> the pilot project in 1995 that recommended expanding the project into a nationwide<br />

programme in a controlled, systematic and planned manner, starting with consolidation in the 8 pilot<br />

project districts<br />

c) Evaluation <strong>of</strong> the functional adult literacy programme in Uganda in 1999 that revealed the<br />

effectiveness and cost-effectiveness <strong>of</strong> the programme and made significant recommendations for its<br />

improvement and consolidation for better results<br />

d) Development and adoption <strong>of</strong> the National Adult Literacy Strategic Investment Plan (NALSIP) in<br />

2002 and inclusion <strong>of</strong> its budget under the privileged Poverty Action Fund raising the government<br />

budgetary allocation for FAL by over five times<br />

e) Inclusion <strong>of</strong> FAL as an important component for community empowerment and mobilisation in the<br />

Government’s Social Sector Development Strategic Investment Plan in 2004<br />

f) Inclusion <strong>of</strong> adult literacy as a strategy in the Government’s revised Poverty Eradication Action Plan<br />

(PEAP) 2004<br />

1.2 Justification for a Process Review<br />

In 2006, it was fourteen years since the countrywide needs assessment study, eleven years since the first<br />

process review and seven years after the comprehensive 1999 evaluation. Much <strong>of</strong> the information<br />

generated by those studies, each <strong>of</strong> which had a different focus, had become outdated in the dynamic<br />

rapidly-changing environment <strong>of</strong> Uganda. The country had in the mean time made significant progress in<br />

the development and implementation <strong>of</strong> the FAL programme. The very momentum with which FAL was<br />

growing had raised new challenges that needed to be addressed in order to sustain the momentum and<br />

answer the new needs and demands that arose from the successes and weaknesses that the programme had<br />

experienced. The following points in particular needed to be addressed:<br />

Changing needs<br />

The initial demands for literacy were basically that people wanted to be able to read, write and develop<br />

basic numeracy skills so that they could improve their status and perform their daily tasks better.<br />

However, as participation in FAL grew, new demands were expressed by the participants, especially<br />

those who had completed the basic cycle. Some required specialised focus e.g. on mathematics, some<br />

demanded examination leading to the issuing <strong>of</strong> recognised certificates and others even demanded for a<br />

parallel education provision providing equivalencies with the mainstream education provision. This raised

Process Review <strong>of</strong> Functional Adult Literacy Programme in Uganda 2002-2006 2<br />

the demand for the development <strong>of</strong> an adult learning qualifications framework to feed into a national<br />

qualifications framework. It was important that the new emerging needs were properly collated and<br />

analysed so that further development <strong>of</strong> the programme would be based on sound up-to-date information,<br />

which would give it a firm footing.<br />

Policy gaps<br />

The growing interest in adult education not only in government but also among Uganda civil society<br />

organisations and international development partners operating in Uganda had brought to the fore the<br />

important gap in policy. Although it was possible to gleam different bits <strong>of</strong> policy relevant to adult<br />

education from various government documents, in particular the Government White Paper on Education<br />

adopted in 1992, it was generally recognised that there should be a comprehensive policy on adult literacy<br />

or adult basic education in general, to form the basis for planning not only by government but also by<br />

civil society organisations and international development partners interested in contributing to the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> adult education. Such a policy, on which work had already started, also needed to be<br />

based on well researched information.<br />

Participation and turn-over<br />

Evidence from the field seemed to suggest a high turn over among both learners and instructors in some<br />

places. It was also not rare that adult literacy classes started and melted away before the basic nine-month<br />

cycle had been completed. The fact that this happened amidst clearly articulated demands for adult<br />

literacy education seemed to point to a mismatch between demand and supply. There was need to<br />

investigate the discrepancy. The statistics also showed that the percentage <strong>of</strong> men who needed literacy<br />

education and were participating in the literacy programme was much smaller than that <strong>of</strong> women who<br />

needed literacy education and were participating. There was need to find out the reasons for the low male<br />