Artificial insemination in the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae ...

Artificial insemination in the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae ...

Artificial insemination in the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Animal Science Papers and Reports vol. 22 (2004) no. 3, 315-323<br />

Institute of Genetics and Animal Breed<strong>in</strong>g, Jastrzębiec, Poland<br />

<strong>Artificial</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong><br />

(<strong>Dromaius</strong> <strong>novaehollandiae</strong>): effects of numbers<br />

of spermatozoa and time of <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong><br />

on <strong>the</strong> duration of <strong>the</strong> fertile period*<br />

Ireneusz Artur Malecki**, Graeme Bruce Mart<strong>in</strong><br />

School of Animal Biology (M085), Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences<br />

The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia<br />

(Received July 15, 2004; accepted September 15, 2004)<br />

In <strong>emu</strong>s, <strong>the</strong> duration of <strong>the</strong> fertile period was measured follow<strong>in</strong>g a s<strong>in</strong>gle artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong><br />

(AI) and <strong>in</strong>vestigated <strong>the</strong> effect of time of AI <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> egg cycle on <strong>the</strong> duration of <strong>the</strong> fertile period.<br />

Semen was collected by artificial cloaca, pooled and used undiluted for AI with<strong>in</strong> 30 m<strong>in</strong>utes. For<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong>, a female was followed until she assumed <strong>the</strong> voluntary crouch. A speculum was <strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>in</strong>serted <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> cloaca and an <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> straw <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> vag<strong>in</strong>a to a depth of 1-2 cm, and<br />

semen deposited. Follow<strong>in</strong>g a s<strong>in</strong>gle <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> with 100, 200 or 400 million spermatozoa, female<br />

<strong>emu</strong>s laid fertilized eggs for 10.0±0.4, 12.0±0.9, and 15.0±0.6 days. When 400 million spermatozoa<br />

were used for <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> on Day 1, 2 or 3 of <strong>the</strong> oviposition cycle, <strong>the</strong> duration of <strong>the</strong> fertile period<br />

appeared to change <strong>in</strong> a day-dependent manner. After AI on Day 1, female <strong>emu</strong>s laid fertilized eggs<br />

for 15.8±1.1 days, after AI on Day 2 for 12.5±2.2 days, and after AI on Day 3 for 10.0±1.5 days. The<br />

results suggest that female <strong>emu</strong>s need to be <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>the</strong> day after oviposition to maximize <strong>the</strong><br />

duration of <strong>the</strong>ir fertile period.<br />

KEY WORDS: artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> / <strong>emu</strong> / fertility / oviposition / ratitae / sperm storage<br />

The <strong>emu</strong> has adapted well to farm<strong>in</strong>g conditions, but monogamous mat<strong>in</strong>g does not<br />

*Supported by <strong>the</strong> Rural Industries Research & Development Corporation <strong>in</strong> Australia<br />

**Correspond<strong>in</strong>g author: e-mail: imalecki@agric.uwa.edu.au<br />

315

I.A. Malecki and G.B. Mart<strong>in</strong><br />

allow efficient production systems to develop and slows genetic improvement. <strong>Artificial</strong><br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> (AI) is thus be<strong>in</strong>g developed for <strong>emu</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g as an alternative to natural<br />

mat<strong>in</strong>g. Naturally mated female <strong>emu</strong>s store spermatozoa <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> tubules <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> oviduct<br />

and release <strong>the</strong>m over a period of time, termed <strong>the</strong> „fertile period” [Lake 1975, Birkhead<br />

1988], dur<strong>in</strong>g which up to 6 eggs can be fertilized [Malecki et al. 1998, Malecki and<br />

Mart<strong>in</strong> 2002b]. When female <strong>emu</strong>s are <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated artificially with doses equal to or<br />

exceed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> average ejaculate volume, <strong>the</strong> fertile period only corresponds to <strong>the</strong> time<br />

needed to lay five eggs. However, <strong>the</strong>se are average values and <strong>the</strong> period dur<strong>in</strong>g which<br />

all females lay fertilized eggs could last for only n<strong>in</strong>e days, effectively guarantee<strong>in</strong>g<br />

only three fertilized eggs as <strong>emu</strong>s lay eggs once every three days [Malecki and Mart<strong>in</strong><br />

2002a]. This suggests that when breed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>emu</strong>s by AI, <strong>the</strong> number of eggs per AI may<br />

be too low for <strong>the</strong> system to be viable. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> duration for which females can store<br />

sperm <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir tubules is highly variable <strong>in</strong> <strong>emu</strong>s [Malecki and Mart<strong>in</strong> 2000a], as it is <strong>in</strong><br />

poultry [Bakst et al. 1994], select<strong>in</strong>g for longer duration of sperm storage could result<br />

<strong>in</strong> longer <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervals thus <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> number of fertilized eggs produced<br />

per <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong>. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imum number of spermatozoa required<br />

for AI could allow large number of females to be sired by a s<strong>in</strong>gle male lead<strong>in</strong>g to a<br />

substantial reduction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> costs of keep<strong>in</strong>g males.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong>, <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imum numbers of spermatozoa that would guarantee maximum<br />

fertility have not been <strong>in</strong>vestigated. However, it has been studied <strong>in</strong> domestic birds,<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> chicken, <strong>in</strong> which 50 to 100 million spermatozoa need to be <strong>in</strong>troduced<br />

weekly [Taneja and Gove 1961, Wishart 1987] and <strong>the</strong> turkey, <strong>in</strong> which 100 to 200<br />

million are needed to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> maximum flock fertility [Sexton 1977, Brillard and<br />

Bakst 1990]. In <strong>the</strong> absence of large numbers of <strong>emu</strong>s to test a range of sperm doses,<br />

we approached <strong>the</strong> problem <strong>the</strong>oretically. The number of spermatozoa required <strong>in</strong> a<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> dose could be estimated from <strong>the</strong> storage capacity of <strong>the</strong> tubules,<br />

termed <strong>the</strong> „sperm storage tubules” (SSTs), as <strong>the</strong>ir numbers and capacity determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

how many spermatozoa can be reta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> oviduct. Theoretically, <strong>the</strong>re should be<br />

sufficient spermatozoa <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> tubules to fertilize an entire clutch [Birkhead and Moeller<br />

1992]. From <strong>the</strong> relationship between <strong>the</strong> female body weight and <strong>the</strong> number of<br />

SSTs [Birkhead and Moeller 1992], <strong>the</strong> utero-vag<strong>in</strong>al region of a 50 kg female <strong>emu</strong><br />

should conta<strong>in</strong> about 27,000 tubules. Based on <strong>the</strong> dimensions of <strong>emu</strong> spermatozoa<br />

and tubules [Malecki 1997], each tubule could hold about 400 spermatozoa and, if <strong>the</strong><br />

tubules were filled to capacity, <strong>the</strong> entire utero-vag<strong>in</strong>al junction would conta<strong>in</strong> about<br />

11 million spermatozoa. This situation is, however, unusual because tubules are rarely<br />

filled to <strong>the</strong>ir maximum capacity and some conta<strong>in</strong> no spermatozoa at all [Compton<br />

and Van Krey 1979, McIntyre and Christensen 1983, Brillard et al. 1987, Brillard and<br />

Bakst 1990, Briskie and Montgomerie 1993]. Never<strong>the</strong>less, if we assume that SSTs<br />

are populated to <strong>the</strong>ir capacity and SST spermatozoa represent about 1-2% of those<br />

deposited dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> female’s vag<strong>in</strong>a [Brillard and Bakst 1990, Brillard<br />

1993], <strong>the</strong>n female <strong>emu</strong>s would require 100-200 million spermatozoa <strong>in</strong> an AI dose.<br />

This dose should produce a fertile period correspond<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> clutch duration.<br />

316

<strong>Artificial</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong><br />

The numbers of spermatozoa that will populate <strong>the</strong> tubules, and thus <strong>the</strong> duration<br />

of <strong>the</strong> fertile period, can also be affected by <strong>the</strong> tim<strong>in</strong>g of <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> oviposition<br />

cycle. In poultry, <strong>the</strong> transport of sperm to <strong>the</strong> SSTs appears to be affected by<br />

oviducal contractions caused by oviposition and, <strong>the</strong> closer to oviposition AI is carried<br />

out, <strong>the</strong> lower <strong>the</strong> fertility rate [Brillard et al. 1987]. As female <strong>emu</strong>s lay eggs every<br />

three days [Malecki and Mart<strong>in</strong> 2002a], <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong>s on Day 3 of <strong>the</strong> cycle (day of<br />

oviposition) should result <strong>in</strong> shorter fertile period than those carried out on Day 1 or<br />

2 of <strong>the</strong> cycle.<br />

We <strong>the</strong>refore determ<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> number of spermatozoa required <strong>in</strong> an AI dose to<br />

produce <strong>the</strong> maximum fertile period and <strong>the</strong> optimum time of <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong> relation<br />

to day of oviposition. Our hypo<strong>the</strong>sis was that, when female <strong>emu</strong>s are <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated with<br />

100-200 million spermatozoa, <strong>the</strong>ir fertile period will correspond to <strong>the</strong> time of clutch<br />

duration, and that <strong>the</strong> fertile period will shorten as <strong>the</strong> time of <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> approaches<br />

<strong>the</strong> proceed<strong>in</strong>g oviposition.<br />

Material and methods<br />

The experiments were approved by <strong>the</strong> Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee<br />

of <strong>the</strong> University of Western Australia. We used adult <strong>emu</strong>s (age 8 to 12 years) held at<br />

<strong>the</strong> Shenton Park Field Station of <strong>the</strong> University of Western Australia (32°13’ S and<br />

115°38’E). The birds were kept <strong>in</strong> pens that conta<strong>in</strong>ed natural vegetation consist<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

grass, shrubs and trees, and <strong>the</strong>y were provided ad libitum with water and a commercial<br />

<strong>emu</strong> breeder ration. The females were <strong>in</strong>itially penned <strong>in</strong>dividually adjacent to pens<br />

that each conta<strong>in</strong>ed a s<strong>in</strong>gle male. Pen area was about 80 m 2 for females and about<br />

40 m 2 for males. The study was carried out over two consecutive breed<strong>in</strong>g seasons:<br />

Experiment 1 <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first, and Experiment 2 <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> second.<br />

Experiment 1<br />

To determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> number of spermatozoa required <strong>in</strong> an AI dose that would produce<br />

maximum duration of <strong>the</strong> fertile period, 12 females (four per AI dose) were <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

once with fresh semen conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ei<strong>the</strong>r 100, 200 or 400 million spermatozoa.<br />

Insem<strong>in</strong>ations were carried out between 09.00 and 10.00 a.m. on Day 1 of <strong>the</strong> egg<br />

cycle (<strong>the</strong> day after oviposition), after female <strong>emu</strong>s had laid two eggs, and eggs were<br />

collected for <strong>the</strong> next four weeks.<br />

Experiment 2<br />

To determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> optimum time of AI that would guarantee maximum duration of<br />

<strong>the</strong> fertile period, we used six females that were randomly assigned to three treatments:<br />

Day 1 (<strong>the</strong> first day after oviposition, 15-17 hours after <strong>the</strong> last oviposition and 55-57<br />

hours prior to <strong>the</strong> next oviposition), Day 2 (second day after oviposition, 31-33 hours<br />

prior to <strong>the</strong> next oviposition) or Day 3 (third day after oviposition, 7-9 hours prior to<br />

<strong>the</strong> next oviposition). Females were <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated once with fresh semen conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 400<br />

317

I.A. Malecki and G.B. Mart<strong>in</strong><br />

million spermatozoa between 09.00 and 10.00 a.m. Females were <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated after two<br />

eggs had been laid and eggs were collected until <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> fertile period, def<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

as when two consecutive unfertilized eggs were laid. We used a lat<strong>in</strong> square design as<br />

potentially every female could be tested for every AI time with<strong>in</strong> one breed<strong>in</strong>g season.<br />

However, lay<strong>in</strong>g that season was not as good as anticipated and one female completed<br />

only one treatment, four females completed two treatments and one completed three<br />

treatments. As a result, each treatment had four replicates.<br />

Semen collection and preparation<br />

Semen was collected from four males us<strong>in</strong>g an artificial cloaca [Malecki et al. 1997],<br />

taken to <strong>the</strong> laboratory and transferred by a graduated glass pipette from <strong>the</strong> collection<br />

vial to <strong>the</strong> storage vial <strong>in</strong> order to separate semen from contam<strong>in</strong>ant particles that<br />

sometimes entered <strong>the</strong> artificial cloaca from <strong>the</strong> male’s fea<strong>the</strong>rs dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> collection.<br />

Spermatozoa concentration was <strong>the</strong>n estimated with a Shimadzu spectrophotometer<br />

and calculated from <strong>the</strong> standard curve. Ejaculate volume ranged from 0.4 to 1.2 mL<br />

and each ejaculate conta<strong>in</strong>ed 1,2-3,5 × 10 9 spermatozoa. The AI pool was made us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

equal numbers of spermatozoa from each male. The concentration of spermatozoa <strong>in</strong> a<br />

pool was subsequently confirmed with a spectrophotometer and <strong>the</strong> volume that would<br />

conta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> required number of spermatozoa was <strong>the</strong>n estimated.<br />

<strong>Artificial</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong><br />

The female is followed until she voluntarily assumes <strong>the</strong> crouch<strong>in</strong>g position (Photo<br />

1-A). Then <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ator lowers himself beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> female and places his hands on her<br />

back to provide stimulation, to which <strong>the</strong> female responds by bend<strong>in</strong>g her neck, rais<strong>in</strong>g<br />

her tail and expos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> vent allow<strong>in</strong>g access to <strong>the</strong> cloaca (Photo 1-B). Subsequently,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ator kneels on <strong>the</strong> ground and puts his leg on <strong>the</strong> female’s back to cont<strong>in</strong>ue<br />

stimulation so <strong>the</strong> female rema<strong>in</strong>s crouched (Photo 1-C). If that was <strong>in</strong>adequate, <strong>in</strong>stead<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ator’s leg, an assistant would put his hands onto <strong>the</strong> female’s back and<br />

press gently. The speculum fitted with light<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>the</strong>n <strong>in</strong>serted <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> cloaca so <strong>the</strong><br />

vag<strong>in</strong>al open<strong>in</strong>g could be seen. The <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> straw, mounted on a tubercul<strong>in</strong> syr<strong>in</strong>ge,<br />

is <strong>the</strong>n <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> cloaca and <strong>in</strong>serted <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> vag<strong>in</strong>a until resistance is felt<br />

(approximately 1-2 cm <strong>in</strong> depth). Deeper <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong>s were not performed to avoid<br />

irritation and possible cessation of lay<strong>in</strong>g (I. Malecki – personal observation). A dose<br />

of sperm is <strong>the</strong>n <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> vag<strong>in</strong>a as <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g straw was gradually<br />

withdrawn (Photo 1-D).<br />

Data analysis<br />

Eggs were stored for up to two weeks and <strong>the</strong>n opened and fertilization status was<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> appearance of <strong>the</strong> germ<strong>in</strong>al disc. Eggs were assumed fertilized when<br />

<strong>the</strong> germ<strong>in</strong>al disc conta<strong>in</strong>ed a blastoderm, or not fertilized when a blastoderm was<br />

absent [Malecki and Mart<strong>in</strong> 2002b]. The duration of <strong>the</strong> fertile period was determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

as <strong>the</strong> number of days from day of <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> to <strong>the</strong> day <strong>the</strong> last fertilized egg was<br />

318

<strong>Artificial</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong><br />

Photo 1. A – female <strong>emu</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>s to crouch voluntarily after be<strong>in</strong>g followed. B – crouch<strong>in</strong>g female <strong>emu</strong><br />

stimulated by rubb<strong>in</strong>g her sides and back. Note <strong>the</strong> bend<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> neck. C – one-person <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong>. While <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> is performed, <strong>the</strong> person ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s stimulation by press<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong>’s back<br />

with his leg. D – <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> of <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g a speculum fitted with a light source and <strong>the</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong><br />

straw mounted on a tubercul<strong>in</strong> syr<strong>in</strong>ge.<br />

laid. One-way ANOVA was used to analyse data, with <strong>the</strong> SuperANOVA TM software<br />

(Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA); data are presented as means ±SEM and P

I.A. Malecki and G.B. Mart<strong>in</strong><br />

lasted for 15.8±1.1 days, after AI on Day 2 it lasted for 12.5±2.2 days and after AI on<br />

Day 3 it lasted for 10.0±1.5 days.<br />

Only <strong>the</strong> largest dose of spermatozoa produced a fertile period that corresponds to<br />

<strong>the</strong> duration of <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong> fertile period follow<strong>in</strong>g artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> and it exceeded<br />

<strong>the</strong> previously estimated period of maximum flock fertility follow<strong>in</strong>g artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong><br />

[Malecki and Mart<strong>in</strong> 2002a]. Loss of spermatozoa viability dur<strong>in</strong>g collection and<br />

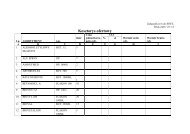

Figure 1. Effect of spermatozoa numbers (A) and time of artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> (B) on <strong>the</strong> duration of <strong>the</strong><br />

fertile period <strong>in</strong> female <strong>emu</strong>s. Bars with different letters differ significantly at P

<strong>Artificial</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong><br />

tions of sperm storage. Moreover, an improvement could be sought by optimiz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

efficiency of <strong>the</strong> artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> technique. Shallow <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong>s can result <strong>in</strong><br />

a loss of spermatozoa from <strong>the</strong> vag<strong>in</strong>a thus reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> number of spermatozoa that<br />

can populate <strong>the</strong> sperm storage tubules [Biellier et al. 1961, Ogasawara and Rooney<br />

1965, Re<strong>in</strong>hart and Fiser 1983]. In <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong>, unforced depth of <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> (no resistance<br />

to <strong>the</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> straw) can vary from 1 to 6 cm between and with<strong>in</strong> females (I.<br />

Malecki – personal observation) mean<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g straw can be <strong>in</strong>serted<br />

to this depth without irritation to <strong>the</strong> vag<strong>in</strong>a. Differences <strong>in</strong> accessibility of <strong>the</strong> vag<strong>in</strong>a<br />

could be due to anatomical variations, or could be related to <strong>the</strong> receptivity of <strong>the</strong> female<br />

because this behaviour appears to be controlled by <strong>the</strong> hormonal changes that are<br />

associated with <strong>the</strong> ovulatory or ovipository cycle [Delville et al. 1986, Shimada and<br />

Saito 1989]. If females could be <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated at <strong>the</strong> time when <strong>the</strong> vag<strong>in</strong>a is <strong>the</strong> most<br />

accessible, deeper <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> would be possible and more spermatozoa should ga<strong>in</strong><br />

access to <strong>the</strong> utero-vag<strong>in</strong>al storage glands [Brillard et al. 1987].<br />

The longest duration of <strong>the</strong> fertile period was achieved with <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong>s carried<br />

out on <strong>the</strong> day after oviposition and <strong>the</strong> decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g trend <strong>the</strong>reafter suggests that a shorter<br />

delay from oviposition to <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> gives a longer fertile period. This relationship<br />

is probably due to <strong>the</strong> time that <strong>the</strong> spermatozoa take to reach <strong>the</strong> storage tubules after<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong>. In <strong>the</strong> turkey and <strong>the</strong> chicken, spermatozoa take up to three days to fill<br />

<strong>the</strong> storage tubules after <strong>the</strong> artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> [Brillard and Bakst 1990] [Bakst et<br />

al. 1994]. Vag<strong>in</strong>al contractions associated with oviposition can affect sperm transfer<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> vag<strong>in</strong>a [Brillard 1993], so <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g female <strong>emu</strong>s on <strong>the</strong> day of oviposition<br />

could result <strong>in</strong> less spermatozoa reach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> SSTs and thus a shorter fertile period,<br />

compared with <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong>s carried out on o<strong>the</strong>r days.<br />

In conclusion, while <strong>the</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> dose for <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong> is yet to be completely<br />

optimized, we do have a good idea of <strong>the</strong> number of spermatozoa required for efficient<br />

AI and we can achieve a high male to female ratio <strong>in</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>emu</strong>s, provided <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

<strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated away from <strong>the</strong> time of oviposition.<br />

Acknowledgement. We thank Miss Caitl<strong>in</strong> Reed and Mr Peter Cowl for <strong>the</strong>ir skilful<br />

technical assistance.<br />

References<br />

1. Bakst M.R., Wishart G., Brillard J-P., 1994 – Oviducal sperm selection, transport, and<br />

storage <strong>in</strong> poultry. Poultry Science Reviews 5, 117-143.<br />

2. Biellier H.V., Paschang P., Funk E.M., 1961 – Effect of depth of <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> on fertility<br />

of Broad Breasted Bronze turkey hens. Poultry Science 40, 1379.<br />

3. Birkhead T.R., 1988 – Behavioural aspects of sperm competition <strong>in</strong> birds. Advances <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Study<br />

of Behaviour 18, 35-72.<br />

4. Birkhead T.R., MOller A.P., 1992 – Numbers and size of sperm storage tubules and <strong>the</strong><br />

duration of sperm storage <strong>in</strong> birds: a comparative study. Biological Journal of L<strong>in</strong>nean Society 45,<br />

363-372.<br />

321

I.A. Malecki and G.B. Mart<strong>in</strong><br />

5. Brillard J-P., 1993 – Sperm storage and transport follow<strong>in</strong>g natural mat<strong>in</strong>g and artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong>.<br />

Poultry Science 72, 923-928.<br />

6. Brillard J-P., Bakst M.R., 1990 – Quantification of spermatozoa <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sperm storage tubules<br />

of turkey hens and <strong>the</strong> relation to sperm numbers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> perivitell<strong>in</strong>e layer eggs. Biology of Reproduction<br />

43, 271-275.<br />

7. Brillard J-P., Galut O., Nys Y., 1987 – Possible cause of subfertility <strong>in</strong> hens follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> near <strong>the</strong> time of oviposition. British Poultry Science 28, 307-318.<br />

8. Briskie J.V., Montgomerie R., 1993 – Patterns of sperm storage <strong>in</strong> relation to sperm competition<br />

<strong>in</strong> passer<strong>in</strong>e birds. Condor 95, 442-454.<br />

9. Compton M.M., Van Krey H.P., 1979 – Empty<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> uterovag<strong>in</strong>al sperm storage glands <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> absence of ovulation and oviposition <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> domestic hen. Poultry Science 58, 187-190.<br />

10. Delville Y., Sulon J., Balthazart J., 1986 – Diurnal variations of sexual receptivity <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> female Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica). Hormones and Behaviour 20, 13-33.<br />

11. LAKE P.E., 1975 – Gamete production and <strong>the</strong> fertile period with particular reference to domesticated<br />

birds. Symposia of <strong>the</strong> Zoological Society of London 35, 225-244.<br />

12. Lake P.E., Stewart J.M., 1978 – <strong>Artificial</strong> Insem<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> Poultry. London, UK. M<strong>in</strong>istry of<br />

Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Bullet<strong>in</strong> 213.<br />

13. Malecki I.A., 1997 – Reproductive competence and artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong> (<strong>Dromaius</strong><br />

<strong>novaehollandiae</strong>). PhD <strong>the</strong>sis, University of Western Australia, pp. 144.<br />

14. Malecki I.A., Holm L., RidderstrAle Y., Mart<strong>in</strong> G.B., 1998 – Sperm storage tubules<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong> (<strong>Dromaius</strong> <strong>novaehollandiae</strong>). Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs of <strong>the</strong> 29th Annual Conference of <strong>the</strong> Australian<br />

Society for Reproductive Biology, 3.<br />

15. Malecki I.A., Mart<strong>in</strong> G.B., 2002a – Fertile period and clutch size <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong> (<strong>Dromaius</strong> <strong>novaehollandiae</strong>).<br />

Emu 102, 165-170.<br />

16. Malecki I.A., Mart<strong>in</strong> G.B., 2002b – Fertility of male and female <strong>emu</strong>s (<strong>Dromaius</strong> <strong>novaehollandiae</strong>)<br />

as determ<strong>in</strong>ed by spermatozoa trapped <strong>in</strong> eggs. Reproduction Fertility Development 14,<br />

495-502.<br />

17. Malecki I.A., Mart<strong>in</strong> G.B., L<strong>in</strong>dsay D.R., 1997 – Semen production by <strong>the</strong> male <strong>emu</strong> (<strong>Dromaius</strong><br />

<strong>novaehollandiae</strong>). 2. Effect of collection frequency on <strong>the</strong> production of semen and spermatozoa.<br />

Poultry Science 76, 622-626.<br />

18. McIntyre D.R. Christensen V.L., 1983 – Fill<strong>in</strong>g rates of <strong>the</strong> utero-vag<strong>in</strong>al sperm storage<br />

glands <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> turkey. Poultry Science 62, 1652-1656.<br />

19. Ogasawara F.X., Rooney W. F., 1965 – <strong>Artificial</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> and fertility <strong>in</strong> turkeys. British<br />

Poultry Science 7, 77-82.<br />

20. Re<strong>in</strong>hart B.S., Fiser P.S., 1983 – Evaluation of artificial <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> techniques on fertility <strong>in</strong><br />

lay<strong>in</strong>g hens. Poultry Science 62, 2285-2287.<br />

21. Sexton T.J., 1977 – Relationship between number of sperm <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated and fertility of turkey hens<br />

at various stages of production. Poultry Science 56, 1054-1056.<br />

22. Shimada K., Saito N., 1989 – Control of oviposition <strong>in</strong> poultry. Critical Reviews <strong>in</strong> Poultry<br />

Biology 2, 235-253.<br />

23. Taneja G.C., Gowe R.C., 1961 – Effect of vary<strong>in</strong>g doses of undiluted semen on fertility <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

domestic fowl. Nature 181, 828-829.<br />

24. Wishart G.J., 1987 – Regulation of <strong>the</strong> length of <strong>the</strong> fertile period <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> domestic fowl by numbers<br />

of oviducal spermatozoa, as reflected by those trapped <strong>in</strong> laid eggs. Journal of Reproduction and<br />

Fertility 80, 493-498.<br />

322

<strong>Artificial</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>emu</strong><br />

Ireneusz Artur Malecki, Graeme Bruce Mart<strong>in</strong><br />

Sztuczne unasienianie <strong>emu</strong> (<strong>Dromaius</strong> <strong>novaehollandiae</strong>) – wpływ<br />

liczby plemników i czasu unasienienia na długość „okresu płodnego”<br />

S t r e s z c z e n i e<br />

Celem badań było określenie długości okresu zapładnialności jaj <strong>emu</strong> po sztucznym unasienieniu i<br />

wpływu czasu unasienienia na długość tego okresu. Nasienie pobierano za pomocą sztucznej pochwy i<br />

samice unasieniano nierozcieńczonym nasieniem w ciągu 30 m<strong>in</strong>ut. Unasieniania dokonywano za pomocą<br />

wziernika, po tym jak samica dobrowolnie usiadła i pozwoliła na dostęp do kloaki. Nasienie deponowano<br />

dopochwowo na głębokość 1-2 cm ze słomki <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>acyjnej osadzonej na strzykawce.<br />

Po jednokrotnym unasienieniu dawką 100, 200 czy 400 milionów plemników samice znosiły<br />

zapłodnione jaja odpowiednio przez okres 10±0,4, 12±0,9 i 15±0,6 dni. Po unasienieniu dawką 400 milionów<br />

plemników w 1, 2 czy 3 dniu cyklu jajowego, długość „okresu płodnego” wyniosła odpowiednio 15,8±1,1,<br />

12,5±2,2 i 10,0±1,5 dni. Wyniki sugerują, że aby uzyskać maksymalną długość okresu zapładnialności jaj<br />

<strong>emu</strong> w trakcie nieśności, unasienienia pow<strong>in</strong>no się dokonywać w pierwszym dniu cyklu jajowego, to jest<br />

w dzień po zniesieniu jaja.<br />

323

324