BADWATER - AdventureCORPS

BADWATER - AdventureCORPS

BADWATER - AdventureCORPS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Choose Category Sunday, Feb. 5, 2006<br />

Sports<br />

Chargers<br />

Padres<br />

Aztecs<br />

Prep Sports<br />

Baseball<br />

NFL<br />

Olympics<br />

NBA<br />

College Football<br />

College Basketball<br />

Golf<br />

Gulls<br />

Outdoors<br />

Soccer<br />

Nick Canepa<br />

Alan Drooz<br />

Chris Jenkins<br />

Jerry Magee<br />

Tim Sullivan<br />

U-T Daily Sports<br />

Sports Forums<br />

Email Newsletters<br />

Wireless Edition<br />

Noticias en Español<br />

<strong>BADWATER</strong><br />

135 miles. 125 degrees. 3 mountain ranges. 2 days. No<br />

IVs. No prize money. It could only be ...<br />

By Mark Zeigler<br />

UNION-TRIBUNE Staff Writer<br />

July 13, 2003<br />

In nine days, 61 men<br />

and 16 women will<br />

attempt the 26th<br />

annual Badwater<br />

Ultramarathon, billed<br />

as "the most<br />

demanding and<br />

extreme running race<br />

offered anywhere on<br />

the planet." Last year,<br />

the Union-Tribune's<br />

Mark Zeigler and Sean<br />

M. Haffey followed the<br />

Badwater from start to<br />

finish. This is their<br />

story:<br />

SEAN M. HAFFEY / Union-Tribune<br />

Ultramarathon veteran Barbara Elia of Modesto sopts<br />

to have blisters examined at Towne Pass, the first<br />

major climb out of the desert.<br />

DEATH VALLEY – First, a quick lesson in geography and meteorology.<br />

As ocean breezes move inland from the California coast, they encounter<br />

several mountain ranges, moving up and over each one. Two things<br />

happen along the way.<br />

The air is sapped of its moisture, because as air rises it condenses into<br />

clouds and deposits its moisture in the form of rain or snow. The air<br />

also gets progressively warmer with each climb and descent, since the<br />

descending air generally heats at a faster rate than the rising air had<br />

cooled.<br />

So a parcel of air going over a particular mountain range, for instance,<br />

might be 80 degrees on one side – and 90 on the other.<br />

Now factor in four steep<br />

mountain ranges, one of<br />

which includes Mount<br />

Whitney, at 14,494 feet the<br />

highest peak in the<br />

contiguous 48 states. And on<br />

the other side, barely 100<br />

miles away, you have Death<br />

Valley, at 282 feet below sea<br />

level the lowest point in the<br />

Western Hemisphere.<br />

Badwater milestones<br />

1973: Paxton Beale and Ken<br />

Crutchlow complete a 150-mile<br />

relay run from Badwater to the<br />

top of Mount Whitney.<br />

1977: Al Arnold completes the<br />

route solo in 84 hours.<br />

Sports Newsletter<br />

Get your daily direct<br />

connection to Sports!<br />

Enter<br />

email:<br />

Submit<br />

Or, Via Cell Phone<br />

Yellow Pages<br />

Bars & Clubs<br />

Business Services<br />

Computers<br />

Education<br />

Health & Beauty<br />

Home & Garden<br />

Hotels<br />

Restaurants<br />

Shopping<br />

Travel<br />

Search by<br />

Company Name:<br />

Go<br />

Local Guides<br />

Baja Guide<br />

Cars<br />

Coupons<br />

Eldercare<br />

Financial Guide<br />

Health<br />

Homes<br />

Home Improvem't<br />

Jobs<br />

Legal Guide<br />

Shopping<br />

Singles Guide<br />

Wedding Guide<br />

The result: very dry air, and<br />

very hot air. Drier and<br />

hotter, in fact, than<br />

anywhere on the planet. A<br />

comfortable ocean breeze<br />

becomes an inferno; 70<br />

degrees Fahrenheit becomes<br />

125.<br />

Mother Nature's pottery kiln.<br />

Now try running 135 miles in<br />

it. In July.<br />

1981: Jay Birmingham breaks<br />

record (75 hours, 34 minutes).<br />

1987: Crutchlow organizes the<br />

first head-to-head race between<br />

Americans and Brits.<br />

1988: Hi-Tec begins<br />

sponsoring the race, now called<br />

the Badwater 146, to promote<br />

its newest running shoe.<br />

1989: Tom Crawford and<br />

Richard Benyo complete the<br />

first Badwater double – from<br />

Badwater to the top of Whitney<br />

and back. It takes126 and 170

9:45 a.m., Badwater, 100<br />

degrees.<br />

If the geography isn't<br />

forbidding and foreboding<br />

enough, there are the names.<br />

Dante's View. Coffin Peak.<br />

Funeral Mountains. Devil's<br />

Golf Course. Desolation<br />

Wash. Dead Man Pass. Hell's<br />

Gate. Death Valley.<br />

Badwater is aptly named as<br />

well. There is water here,<br />

and it is bad – a toxic, putrid<br />

stew of alkalis that would kill<br />

you if you drank enough of it.<br />

and back. It takes126 and 170<br />

hours, respectively.<br />

1996: The time required to<br />

earn a Badwater belt buckle is<br />

raised from 45 to 48 hours.<br />

2000: Anatoli Kruglikov of<br />

Russia sets the 135-mile course<br />

record of 25:09:05.<br />

2002: Pam Reed lowers the<br />

women's record to 27:56:47.<br />

2003 Badwater<br />

Ultarmarathon<br />

When: July 22-24<br />

Who: 61 men, 16 women from<br />

around the world<br />

Live Webcast:<br />

www.badwaterultra.com.<br />

It is here that the Badwater<br />

135 road race begins, next to<br />

a smelly pond and a wooden<br />

sign that says you are 280<br />

feet below sea level. The<br />

tradition is for the competitors to pose around the wooden sign, then<br />

walk 50 yards to the road and begin their 135-mile odyssey through the<br />

desert, over two mountain passes, across an endless valley and finally –<br />

one, two, sometimes three days later – halfway up Mount Whitney.<br />

Assuming you get that far.<br />

Racers face temperature<br />

changes of up to 90<br />

degrees, and 13,000 feet<br />

in cumulative altitude<br />

gains and 4,700 feet in<br />

knee-crunching<br />

descents. There are<br />

sidewinder rattlesnakes<br />

just off the road,<br />

coyotes, scorpions,<br />

tarantulas and<br />

mountains lions. One<br />

year a racer was buzzed<br />

by a rabid bat. Another<br />

year a family of bears<br />

was spotted near the<br />

finish line at Whitney<br />

Portal.<br />

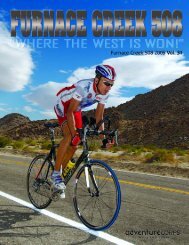

SEAN M. HAFFEY / Union-Tribune<br />

135 miles. 125 degrees. 3 mountain ranges. 2 days.<br />

No IVs. No prize money. It could only be ...<br />

Badwater. Above, blurred by the heat radiating off<br />

the pavement, Ian Parker, a Badwater rookie from<br />

Irvine, learns firsthand the toll Death Valley exacts.<br />

In the Owens Valley, fighter jets from Edwards Air Force Base appear<br />

out of nowhere and make strafing runs at perilously low heights, which<br />

causes all sorts of psychological havoc on physically exhausted, sleepdeprived,<br />

severely dehydrated runners prone to vivid hallucinations.<br />

There is also the swirling wind, and the occasional sand storm or<br />

lightning strike. In this race, two fires on the other side of the Sierra<br />

send their choking smoke into racers' lungs.<br />

But mostly there is the raw heat. Relentless. Merciless. Endless. It<br />

drains your body of precious water. It fries your mind's motherboard<br />

and shuts down its circuitry. It evaporates your inner will, one drop of<br />

sweat at a time.<br />

Rubber soles melt. Air heel cushions burst. Raw skin bubbles. One<br />

competitor talks wistfully about the record-setting heat in 1998, when<br />

air temperatures reached 130 and "my toenails exploded like kernels of<br />

popcorn." Most racers bring seven, eight, nine pairs of running shoes in<br />

progressively larger sizes because their feet swell so much.<br />

Did we mention that IVs are prohibited during the race and there are<br />

no official aid stations?<br />

"If you had aid stations," race director Chris Kostman says, "first of all<br />

the people in the aid stations would die."<br />

The 80 competitors are divided into three flights, with 6, 8 and 10 a.m.<br />

starts. The 10 a.m. group gathers around the wooden sign and looks<br />

back at Kostman and his camera.<br />

"We've already had our first 911 call," Kostman tells the competitors in

a monotone as dry as the air around them. "Let's hope it's our only one<br />

today. Someone has already passed out a couple of times. On that note,<br />

welcome to the 25th Badwater 135.<br />

"Smile, guys."<br />

His name is Derek McCarrick. He is from Isle of Sheppey, England.<br />

He is a 67-year-old coal miner-turned-taxi driver, and he runs<br />

marathons and other ultradistance events as a hobby. He raises money<br />

for charities, mostly for breast cancer (which claimed his wife) and<br />

leukemia (which claimed a friend's daughter).<br />

His schtick is that he wears a rabbit suit, with furry pants and a furry<br />

top and a furry rabbit head with floppy ears. He's run the London<br />

Marathon 21 times and is known simply as "Roger Rabbit" to fans and<br />

race organizers. Kids lining the course love him.<br />

In the months before the 2002 Badwater, Kostman receives<br />

McCarrick's entry application. Kostman calls him and explains that he<br />

meets all the necessary qualifications, but "you can't possibly wear that<br />

rabbit outfit here."<br />

No problem, McCarrick tells Kostman. He has a special desert suit. He<br />

wore it in the Marathon des Sables, a six-day, 151-mile event across the<br />

Sahara in April.<br />

"So I sort of pictured a (baseball) hat with small bunny ears on it and a<br />

bunny silk-screened on his shirt, shorts and running shoes," Kostman<br />

says.<br />

McCarrick shows up for his 6 a.m. start with long, furry pants, floppy<br />

rabbit feet over his shoes and a giant green bow. That is his first<br />

mistake. His second: Drinking only 1-1/2 liters of water over the first<br />

nine miles, when most medical experts recommend a liter per mile.<br />

Three hours into the race, McCarrick is slumped in the passenger seat<br />

of his crew's minivan, comatose. When his condition does not improve<br />

markedly over the next several hours, he withdraws to avoid becoming<br />

the first person in race history to die.<br />

Kostman shakes his head. Another year, another victim.<br />

"This race is just so far beyond any other running event that it's just in<br />

a league of its own," says Kostman, whose adventureCORPS company<br />

organizes several other endurance events. "Most of the top 100-mile<br />

runners won't do this race because they're scared. They're afraid they'll<br />

discover they're out of their element, afraid to discover they won't be<br />

competitive.<br />

"One-hundred-mile racers, their paradigm is that what they do is the<br />

toughest thing. They're like an ostrich with their head stuck in the<br />

sand, because what they do is not the toughest thing. This is."<br />

Ann Trason is considered the queen of ultrarunning, having won the<br />

women's division of the grueling Western States 100 a record 14 times.<br />

She tried Badwater once – as part of someone's support crew that<br />

follows a racer in a minivan. She wants no part of racing it.<br />

"It's more of a hike, a 130-degree-in-a-sandstorm hike, a torture-fest<br />

that I don't want to repeat," Trason told Ultrarunning magazine. "I like<br />

adventure, but this is an out-of-this-world experience. I drank more<br />

crewing Badwater than I did running Western States.<br />

"I felt like I was in 'Star Trek' – and I wanted to be beamed out."<br />

The carnage is not reserved for 67-year-old Isle of Sheppey cabbies in<br />

furry bunny suits. (Or for a Japanese doctor who is studying the effects<br />

of heat on runners and passes out herself, despite spending most of the<br />

day in an air-conditioned car.)<br />

The leader for the first 50 miles, John Quinn, had painstakingly<br />

developed calluses on his feet so blisters wouldn't end his race as they<br />

had in the past. Instead he develops blisters underneath his calluses on<br />

the way up 4,965-foot Towne Pass, can't drain them with a hypodermic<br />

needle and withdraws.<br />

There is Germany's Achim Heukemes. Six weeks earlier he had run<br />

1,000 miles over 11 days through the streets of Hamburg, stopping for<br />

2-1/2 hours each night to sleep. In 2001 he covered 234 miles in a 48-<br />

hour event in a French stadium, which was eight miles short of the

ecord he set two years earlier. He shows up in Death Valley and tells<br />

people two things, that he's going to run the entire 135 miles without<br />

stopping and that he's going to win.<br />

He doesn't make it to the 72-mile checkpoint, either. His body shuts<br />

down and refuses to digest food.<br />

"You feel good, good, good, and then you break down," Heukemes says.<br />

"Usually you rest an hour and you come back. But here, you don't<br />

come back."<br />

Or there is Brazil's Manoel de Jesus Mendes, another of the prerace<br />

favorites who says on his entry form that "being able to surpass the<br />

limits of my body and mind has become my main objective in life." At<br />

midnight the first day, he is lying in a fetal position on the side of the<br />

road, sobbing.<br />

Assesses the race's medic: "He just emotionally grenaded."<br />

The 10 a.m. flight of runners stands at the start and listens to the<br />

national anthem played from a car stereo. Someone in the back of a<br />

pickup truck holds aloft an American flag, which hangs limp in the<br />

already suffocating heat.<br />

There is no starter's pistol. There is a 10-second countdown and a tall,<br />

aging man says: "Bang."<br />

The man is 75-year-old Al Arnold, the godfather of Badwater. "I see<br />

more cars in the parking lot right now than I did during the entire race<br />

in 1977," he says, "and that's counting through traffic along the roads. I<br />

had no clue this thing would ever take off."<br />

Arnold uses the term "race" loosely. Back then, the Badwater was less a<br />

competition than a challenge – less an organized test of endurance<br />

than a barroom dare.<br />

In 1973 Arnold heard about two men completing a 150-mile relay run<br />

from Badwater to the top of Mount Whitney in the dead of summer.<br />

Being something of an adventure junkie himself, Arnold persuaded<br />

buddy David Gabor to do it with him in 1974 – only not as a relay.<br />

Gabor lasted 5-1/2 miles.<br />

"It hit him like a ton of bricks," Arnold says. "His entire nervous<br />

system shut down and he went into shock. He almost died. They took<br />

him to the Furnace Creek Ranch (hotel) and filled a bathtub with ice<br />

and stuck him in it for 10 hours. He was very sick for about a year after<br />

that."<br />

Worried about the welfare of his friend, Arnold quit a few hours later.<br />

He tried again the following year, preparing for the desert ferocity by<br />

riding a stationary bike in a 165-degree sauna, but his knee went out<br />

on Towne Pass and he quit again.<br />

In 1977 Arnold returned in even better shape. This time, he cranked up<br />

the sauna to 200 degrees and made daily runs up Mount Diablo near<br />

his home in the San Francisco Bay Area.<br />

Eighty-four hours after leaving Badwater, he was standing on top of<br />

Whitney. He had lost 17 pounds.<br />

He never did it again, but he didn't need to. He had created a monster.<br />

For the next decade, the Badwater was a solo "race" against the clock.<br />

The first head-to-head competition was in 1987 and it was called the<br />

Badwater 146, the extra 11 miles being the distance between Whitney<br />

Portal and the peak.<br />

In 1989, the U.S. Forest Service forced the race to end at Whitney<br />

Portal, elevation 8,360 feet – something about not holding athletic<br />

competitions in designated wilderness areas. Each year a few nostalgic<br />

competitors will obtain their own hiking permits and complete the old<br />

route; most, however, figure they've made their point when they cross<br />

the finish line adjacent to the Whitney trailhead.<br />

And exactly what is that point?<br />

It's a simple question, and a complex one. Why?<br />

There is no prize money in the Badwater. There is no live TV and there

is minimal newspaper coverage. You get a T-shirt for entering and a<br />

belt buckle if you finish under 48 hours.<br />

You are required to sign a medical waiver that begins: I acknowledge<br />

that this athletic event is an extreme test of a person's physical and<br />

mental limits and carries with it the potential for death.<br />

You pay $250 in entry fees (plus $2,000 or $3,000 in crewing<br />

expenses) for the privilege of running through a desert in late July and<br />

halfway up the Lower 48's highest peak. Most people take vacation<br />

from stable jobs to do it.<br />

"You say Badwater and no one has ever heard of it," says Kostman, the<br />

race director. "They're not doing it to bring recognition from the public<br />

at large, because the public at large doesn't know about it. And if you<br />

try to explain it to people, they can't fathom it. People do this for their<br />

own personal reasons."<br />

There are cancer survivors here, intent on taking their invincibility a<br />

step further. There are recovering alcoholics. There are political<br />

refugees from oppressive foreign regimes. There are people who do it<br />

because, as one man says, "equipment, status and personal wealth have<br />

little do with one's success in this sport." There are people who do it<br />

because, as a Badwater veteran puts it, "I'm good at it."<br />

There are people who started running 10ks, then graduated to<br />

marathons, then graduated to ultramarathons, then find themselves<br />

standing beside a smelly pond and a wooden sign in the depths of<br />

Death Valley in late July.<br />

"Maybe there's some masochistic element in your makeup that makes<br />

you want to do it," says Ben Jones, a physician in nearby Lone Pine<br />

and the so-called mayor of Badwater. "It's like why did Norgay and<br />

Hillary climb Everest – because it was there. I think people do this to<br />

see if they can get away with it."<br />

Ten minutes before the 10 a.m. start, 53-year-old Steven Silver of El<br />

Paso, Texas, walks up to Arnold and shakes his hand.<br />

"I've done this five times, Al, and I want to thank you," Silver says.<br />

"I could have been sitting in my office right now, getting ready to eat<br />

lunch, with a beautiful secretary. Instead I'm out here.<br />

"Thank you."<br />

5 p.m., Stovepipe Wells, 125 degrees.<br />

Reg Richard is lying in the pool at the Stovepipe Wells Village, a motel<br />

at mile 42 that sits at the base of the race's first major climb. The pool<br />

water is close to 90 degrees. Richard is shivering uncontrollably.<br />

Richard's fiancee, Mary Berry, met him at a hospital in Dayton, Ohio,<br />

where she's a nurse and he's a physical therapist. Being medically<br />

proficient (and conscientious), Berry has been meticulously charting<br />

her 51-year-old fiance's progress through the desert.<br />

Every 20 minutes she gives him a new plastic bottle with 20 ounces of<br />

fluid and records how much is left in the old one. She also conducts a<br />

periodic roadside urinalysis, using a test strip to measure his levels of<br />

glucose, bilirubin, urobilirubin, ketone, specific gravity, blood, pH<br />

protein, nitrate and leukocytes.<br />

The charts are clear. Richard is crashing.<br />

For the first few hours after his 8 a.m. start, he returns every water<br />

bottle empty. Then there is a little left in the bottom, then a little more.<br />

At 11:30 he stops urinating. At 1:45 p.m. he drinks only four of 20<br />

ounces.<br />

Then he vomits five times, is helped into his crew's car and passes out.<br />

It is almost exactly the same place he bonked the year before.<br />

Each competitor is given a numbered wooden stake, which he or she<br />

can stick into the side of the road if they want to leave the course and<br />

rest. When Richard's body temperature soars to 104, Berry pounds in<br />

the stake at 4:30 p.m. and drives him to the motel at Stovepipe.<br />

Richard spends the next few hours in and out of the pool in an effort to<br />

lower his body temperature. It's a tedious process. Every time Richard<br />

starts shivering, Berry pulls him out and lays him on a lounge chair

with wet towels covering him. The shivering is counterproductive<br />

because it requires energy and thus burns fuel, which raises the body's<br />

temperature again.<br />

Richard stops shivering and slides back into the pool.<br />

"I can't comprehend the mentality of wanting to do this," Berry says.<br />

"But what I could see in the last seven months together was how<br />

important this is to him ... He says it's a feeling of accomplishment.<br />

But we agree this would be the last time (at Badwater).<br />

"Because this is scary. What makes it hard is when you love somebody,<br />

because you lose your objectivity a little bit."<br />

Richard had trained by running around his Ohio neighborhood on<br />

steamy afternoons wearing three sweaters and a ski cap. He spent<br />

hours sitting in a sauna at 211 degrees. He ran seven hours straight on<br />

the hospital's treadmill.<br />

Nothing, though, can simulate the mental and physical toll Death<br />

Valley exacts in July, the monotonous hours spent shuffling past sage<br />

brush and salt flats and sand dunes, accompanied only by the sound of<br />

shoes crunching on the scorching pavement and coarse gasps for<br />

breath.<br />

It is a cruel choice. Run through the desert and you risk pushing your<br />

body to collapse. Walk though the desert and you spend more time in<br />

the crushing heat.<br />

And you never really escape it, even when you climb to higher<br />

elevations. The temperature in Lone Pine (elev. 3,610 feet) on the<br />

race's two days is 96 and 95.<br />

"You know when you're baking cookies and you open the oven door and<br />

that blast of heat hits you?" says Steve Teal, a firefighter and<br />

paramedic who serves as the race medic. "It's cool because you can<br />

close the oven door. Out here, you can't do that.<br />

"People say you can acclimate to it. But when I turn my oven up to 350,<br />

it still cooks that cupcake. The cupcake never gets used to it."<br />

Richard returns to his stake in the desert that night and makes it the 10<br />

miles to Stovepipe Wells, but he starts to fade again and finally agrees<br />

to sleep at the motel until 9 the next morning. At noon he still can't<br />

urinate and withdraws from the race.<br />

The desert has won again.<br />

Less than an hour after Richard gives up, the winner of the 25th<br />

Badwater 135 is crossing the finish line 93 miles away at Whitney<br />

Portal.<br />

The winner is a 41-year-old ultramarathon veteran from Tucson.<br />

The winner is a 5-foot-3, 100-pound Badwater rookie.<br />

The winner is a woman.<br />

Pam Reed finishes in 27 hours, 56 minutes, 47 seconds, breaking the<br />

women's course record by more than an hour, which had shattered the<br />

previous record by seven hours. She runs about 90 percent of the time,<br />

walking only the steepest mountain grades. She doesn't eat any solid<br />

foods (instead consuming an all-liquid diet that includes eight cans of<br />

the energy drink Red Bull). She never vomits. She never changes shoes.<br />

She loses only 6 pounds, which also has to be some kind of Badwater<br />

record.<br />

"It took me a long time, up until a couple of months ago, to realize it<br />

was 135 miles," Reed told the Arizona Daily Star in December. "It<br />

didn't feel that hard."<br />

Reed wakes up the following day, returns to the finish line and hikes<br />

up the rest of Whitney with a friend.<br />

In many respects, her Badwater experience is an aberration, some sort<br />

of cosmic exception. It is not a death slog over two days and three<br />

mountains, a literal and figurative test of intestinal fortitude. She never<br />

has so much as one hallucination, not even a single panda or<br />

pterodactyl.

"I'm grateful for doing it as fast as I did so I didn't make my crew stay<br />

out there any longer," Reed says. "I kept asking them, 'Am I going too<br />

slow?' "<br />

Most crews use minivans, stuffed with food, water and a mindboggling<br />

array of supplies – shoes, socks, ice chests, scales, towels,<br />

flashlights, folding chairs, umbrellas, sunscreen, first-aid kits, even<br />

giant squirt guns to hose down racers. It is tough going, though,<br />

leapfrogging ahead of the racer every mile and preparing for the<br />

endless pit stops. The crew members are part medic, part nutritionist,<br />

part chauffeur, part water boy, part equipment manager, part<br />

psychologist.<br />

By the time they reach the base of Mount Whitney, they are imagining<br />

things, too.<br />

It is another five hours before the first man reaches Whitney Portal, 31-<br />

year-old Darren Worts of Chatham, N.J. He crosses the finish line with<br />

a vacant look on his face, crumples into a white plastic chair and<br />

mutters: "One tough race ... unbelievable ... just brutal."<br />

One by one, they trudge up the mountain, the same cocktail of<br />

desperation and determination in their eyes. There are Badwater<br />

veterans such as Silver, who finishes in 38 hours and claims his fifth<br />

belt buckle despite vowing to quit after his fourth. And Maj. Curt<br />

Maples, a Marine from Oxnard who trains by wearing a Haz-Mat suit<br />

while dragging a car tire behind him.<br />

And Marshall Ulrich, an ultramarathoning legend who once completed<br />

the course solo by pulling a 200-pound rickshaw with solar panels to<br />

power flashing tail lights and a water pump.<br />

There are Germans Uli Weber and Eberhard Frixe, who complete the<br />

vaunted Badwater double – doing the course in reverse and arriving at<br />

the starting line just in time to turn around.<br />

"We must sit down a little bit," Weber says after celebrating briefly at<br />

the finish line.<br />

There is also Vito Bialla, a 53-year-old Badwater rookie.<br />

The first time he trained in Death Valley, he ran four hours in 110-<br />

degree heat and started crying "for no reason." During the race, in the<br />

never-ending stretch of high desert before Lone Pine, he bends over to<br />

stretch and notices "thousands of bats flapping their wings."<br />

Plants turn into dinosaurs.<br />

He swears there's a piano in the middle of the road.<br />

At 5:52 a.m. on Thursday, nearly two full days after he starts, he<br />

reaches Whitney Portal.<br />

"I'm numb as I cross the finish line, too tired to cry," Bialla writes in a<br />

first-person account posted on the race's Web site. "I am overwhelmed<br />

and still not fully comprehending what has transpired. Maybe as I<br />

unwind I'll figure it out.<br />

"Right now as I sit on a plane back to London with family, I feel like a<br />

servant of the gods who was allowed to play in their back yard for a<br />

couple of days, and survive."<br />

Site Index | Contact SignOn | UTads.com | About SignOn | Advertise on SignOn | Make SignOn your homepage<br />

About the Union-Tribune | Contact the Union-Tribune<br />

© Copyright 2003 Union-Tribune Publishing Co. .