Urban Animals - Art Gallery of Alberta

Urban Animals - Art Gallery of Alberta

Urban Animals - Art Gallery of Alberta

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

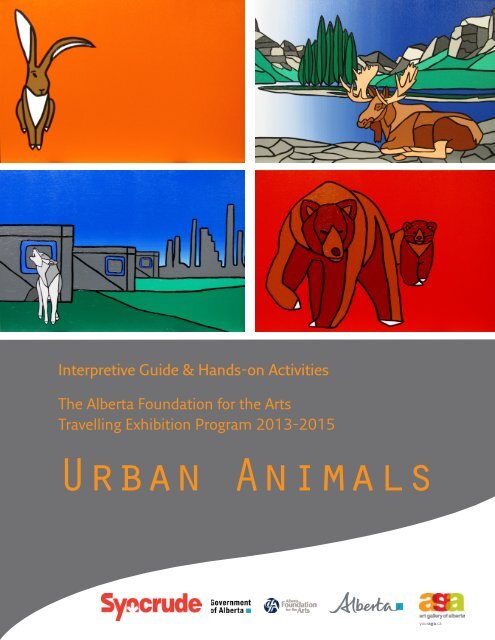

Interpretive Guide & Hands-on Activities<br />

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

Travelling Exhibition Program 2013-2015<br />

<strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Animals</strong><br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

The Interpretive Guide<br />

The <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong> is pleased to present your community with a selection from its<br />

Travelling Exhibition Program. This is one <strong>of</strong> several exhibitions distributed by The <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong> as part <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program. This<br />

Interpretive Guide has been specifically designed to complement the exhibition you are now<br />

hosting. The suggested topics for discussion and accompanying activities can act as a guide to<br />

increase your viewers’ enjoyment and to assist you in developing programs to complement the<br />

exhibition. Questions and activities have been included at both elementary and advanced levels<br />

for younger and older visitors.<br />

At the Elementary School Level the <strong>Alberta</strong> <strong>Art</strong> Curriculum includes four components to provide<br />

students with a variety <strong>of</strong> experiences. These are:<br />

Reflection: Responses to visual forms in nature, designed objects and artworks<br />

Depiction: Development <strong>of</strong> imagery based on notions <strong>of</strong> realism<br />

Composition: Organization <strong>of</strong> images and their qualities in the creation <strong>of</strong> visual art<br />

Expression: Use <strong>of</strong> art materials as a vehicle for expressing statements<br />

The Secondary Level focuses on three major components <strong>of</strong> visual learning. These are:<br />

Drawings: Examining the ways we record visual information and discoveries<br />

Encounters: Meeting and responding to visual imagery<br />

Composition: Analyzing the ways images are put together to create meaning<br />

The activities in the Interpretive Guide address one or more <strong>of</strong> the above components and are<br />

generally suited for adaptation to a range <strong>of</strong> grade levels. As well, this guide contains coloured<br />

images <strong>of</strong> the artworks in the exhibition which can be used for review and discussion at any time.<br />

Please be aware that copyright restrictions apply to unauthorized use or reproduction <strong>of</strong> artists’<br />

images.<br />

The Travelling Exhibition Program, funded by the <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s, is designed to<br />

bring you closer to <strong>Alberta</strong>’s artists and collections. We welcome your comments and<br />

suggestions and invite you to contact:<br />

Shane Golby, Manager/Curator<br />

Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Ph: 780.428.3830; Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

Email: shane.golby@youraga.ca<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479 youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

This package contains:<br />

Curatorial Statement<br />

Visual Inventory - list <strong>of</strong> works<br />

Visual Inventory - images<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist and Curator Biographies/Statements<br />

A Brief Interview with Jason Carter<br />

Talking <strong>Art</strong><br />

Curriculum Connections/<strong>Art</strong> Across the Curriculum<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> in Mythology and Symbolism<br />

<strong>Animals</strong>: First Nations Beliefs and Stories<br />

<strong>Animals</strong>: Scientific Studies<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> in <strong>Art</strong>/<strong>Art</strong> Movements<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> in <strong>Alberta</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

An <strong>Urban</strong> Animal Story - news report<br />

Visual Learning and Hands-on Projects<br />

What is Visual Learning?<br />

Elements and Principles <strong>of</strong> Design Tour<br />

Reading Pictures Tour<br />

Perusing Paintings: An <strong>Art</strong>-full Scavenger Hunt<br />

Exhibition Related <strong>Art</strong> Projects<br />

Glossary<br />

Credits<br />

Syncrude Canada Ltd., the <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s, the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong><br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479 youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Curatorial Statement<br />

<strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Animals</strong><br />

into the minds <strong>of</strong> these rural animals now<br />

living in an urban world.<br />

Jason Carter’s fascination with urbanization<br />

started at a young age. Prairie dogs, moose,<br />

brown and/or black bear (amongst others) were<br />

not uncommon to come face to face with across<br />

the prairies <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong> as towns and cities<br />

expanded. This development encroached upon<br />

land that had already been occupied not so<br />

much by man, but by animals. These animals<br />

would roam freely and, more importantly, safely<br />

through a land that provided them with food,<br />

shelter, and very <strong>of</strong>ten a sense <strong>of</strong> family and<br />

belonging. We as humans understand what it<br />

is like to have a home, a neighborhood, a ro<strong>of</strong><br />

over our head…but imagine if all that changed<br />

and you came home one day to find that your<br />

home had been moved, compromised or worse,<br />

eradicated?<br />

Jason’s latest series <strong>of</strong> 18 paintings intends to<br />

illustrate just that. He uses a modified<br />

triptych (three paintings) for each animal to tell<br />

the story. He uses the term ‘modified’ because<br />

normally a triptych consists <strong>of</strong> three paintings<br />

forming one image; here, there are three<br />

paintings forming one story. The first painting in<br />

the triptych is dedicated to the animal with<br />

nothing to distract from it except the colour<br />

and colour only enhances the animal. Jason<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten treats the colour in his paintings as the<br />

second subject, <strong>of</strong>ten equally as important as<br />

the main subject. Colour can be emotional or<br />

inspirational and has a subtext <strong>of</strong> it’s own. The<br />

colour established in the first painting is carried<br />

through to the second painting, where these<br />

animals are shown in their natural habitat: the<br />

prairies, the mountains, the river valley and so<br />

on. It is Jason’s intention to evoke a sense <strong>of</strong><br />

the beauty and expansiveness <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> these<br />

animal’s natural habitats. Finally, the last<br />

painting in the triptych suggests what the<br />

‘natural habitat’ may look like now. It is not<br />

meant to shame or discourage expansion or<br />

industrialization: rather it is a fun exploration<br />

We can learn a lot from these animals about<br />

adaptation and resilience as we move<br />

forward in this ever-evolving world. It is<br />

Jason’s hope that this latest series will create<br />

a new consciousness and continue the<br />

dialogue regarding the land we live on and<br />

who or what we share it with!<br />

Bridget Ryan<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The City Moose, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

The exhibition <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Animals</strong> was curated by<br />

Bridget Ryan and Jaret Sinclair-Gibson and<br />

organized by the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong> for the<br />

<strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling<br />

Exhibition Program. The AFA Travelling Exhibition<br />

program is supported by the <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation<br />

for the <strong>Art</strong>s.<br />

The exhibition <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Animals</strong> was made<br />

possible through generous sponsorship from<br />

Syncrude Canada Ltd.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Visual Inventory - List <strong>of</strong> Works<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Mother Bear and her Cub, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Mother Bear and her cub in the backcountry <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Alberta</strong>, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Mother Bear and her cub in the back alleys <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Alberta</strong>, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Beaver, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Habitat for a Beaver, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Habitat for Humanity, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Moose, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Country Moose, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The City Moose, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Prairie Dogs, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Prairie Dogs on the Open Prairie, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Prairie Dogs on the Open Road, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Rabbit, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Rabbit Hole, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Visual Inventory - List <strong>of</strong> Works<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Man Hole, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Wolf, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Wolf and the Moon, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Wolf and Oil, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

20 inches X 30 inches<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Total Images: 18 2D works<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Visual Inventory - Images<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Mother Bear and her Cub, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Mother Bear and her cub in the<br />

backcountry <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong>, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Mother Bear and her cub in the back<br />

alleys <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong>, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Beaver, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Visual Inventory - Images<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Habitat for a Beaver, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Habitat for Humanity, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Moose, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Country Moose, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Visual Inventory - Images<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The City Moose, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Prairie Dogs, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Prairie Dogs on the open prairie,<br />

2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Prairie Dogs on the open road,<br />

2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Visual Inventory - Images<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Rabbit, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Rabbit Hole, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Man Hole, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Wolf, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Visual Inventory - Images<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Wolf and Moon, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Wolf and Oil, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist and Curator Biographies/Statements<br />

Jason Carter<br />

Jason Carter is one <strong>of</strong> Canada’s most exciting and accomplished visual artists. At the age <strong>of</strong> 31<br />

he was the only artist in <strong>Alberta</strong> to have had a feature showing at <strong>Alberta</strong> House on <strong>Alberta</strong> Day<br />

at the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics, and as such, was publicly acknowledged by the<br />

Honorable Lindsay Blackett at an International Press Conference kicking <strong>of</strong>f the event. Jason<br />

has had three solo shows in the past two years and has been commissioned by the Winter Light<br />

Festival two years in a row to design a billboard for their promotional campaign. His work can<br />

be found in dozens <strong>of</strong> private collections (Mayor Stephen Mandel, Edmonton; the <strong>Alberta</strong><br />

Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s collection; Alice Major; and Rogers Media to name a few) as well as<br />

several exciting public collections, including the Edmonton International Airport where he<br />

created a mural which resides above the International Departures Gate. On April 16, 2011,<br />

Jason launched his first children’s book, ‘Who Is Boo: The Curious Tales <strong>of</strong> One Trickster Rabbit’<br />

(based on the character inspiraton <strong>of</strong> Nanabozho) at the Royal <strong>Alberta</strong> Museum. Recent<br />

exhibitions included Jasper: The Canvas and Stone Series in Jasper, <strong>Alberta</strong> (2011), as well as<br />

A Year <strong>of</strong> the Rabbit (2011) in Edmonton. His work is currently represented by The Bearclaw<br />

<strong>Gallery</strong>, Edmonton; Nativeart <strong>Gallery</strong>, Oakville, Ontario; and The Carter-Ryan <strong>Gallery</strong>,<br />

Canmore, <strong>Alberta</strong>. Jason Carter lives and works in Edmonton and is a member <strong>of</strong> the Little<br />

Red River Cree Nation.<br />

Jason Carter: <strong>Art</strong>ist’s Statement<br />

Being an artist who divides their time equally between painting and carving, I have been gifted<br />

with the opportunity to express myself through two mediums, stone and canvas, and both I<br />

approach with humor and optimism. In the world we live in, there is much to be cynical about,<br />

but I have found an outlet that I, myself, gather much joy and light, and am so fortunae to be<br />

able to pass that joy on. As an Aboriginal man from the Little Red River Cree Nation, I gather<br />

much inspiration from the stories passed on by elders within my community, stories that have<br />

evolved and changed, some documented, some not, but the essence <strong>of</strong> these characters are<br />

passed on through the years. As an artist, I am inspired by the essence <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> these<br />

characters and then, in keeping with the tradition <strong>of</strong> my indigenous roots, create new stories<br />

filled with wonder and morals, and bring them to life through my chosen medium, canvas and<br />

stone with written word.<br />

As a contemporary Aboriginal artist in pursuit <strong>of</strong> becoming my true authentic self (in this ever<br />

evolving culture), I am aware that much <strong>of</strong> my craft comes from an innate ability that I have been<br />

born with, and believe this to be a blessing and a responsibility, both <strong>of</strong> which I take very<br />

seriously. I am continuously using my gift to create new stories inspired from traditional<br />

characters with my stone and canvas. I seek inspiration from the past as I create a bold and<br />

colourful future.<br />

I have fearlessly painted animals big and small. I am drawn to paint with colours that many<br />

would not. I believe in the empty space on canvas. I believe that colour can give us something<br />

image can not. Conversely, I enjoy breaking down the most complex animals to the very<br />

essence <strong>of</strong> their being. I have, to a certain degree, defined my paintings through these terms.<br />

Until now I have always wanted to paint a mountain. The inspiration I have found in the Rocky<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist and Curator Biographies/Statements<br />

Mountains as <strong>of</strong> late, the feeling <strong>of</strong> largeness and smallness at the same time, and always<br />

peaceful, has led me to a new place in my work. It was time to take the leap; combine essence<br />

with certainty, blends with bold and move forward. People have commented that they find a<br />

certain ‘happiness’ with my work. I truly hope you can feel the joy in it as well.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist and Curator Biographies/Statements<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist and Curator Biographies/Statements<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist and Curator Biographies/Statements<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist and Curator Biographies/Statements<br />

Bridget Ryan<br />

Bridget Ryan is an actor, singer, playwright, director and television host in Edmonton, <strong>Alberta</strong>,<br />

Canada. She graduated from MacEwan University as well as from the University <strong>of</strong> Cincinnati’s<br />

College Conservatory <strong>of</strong> Music with a BFA in Musical Theatre. She has performed in several<br />

national tours before getting <strong>of</strong>f the stage to work alongside producers Richard Frankel, Marc<br />

Routh, Darryl Roth and Scott Rudin.<br />

Bridget has performed at theatres all over Canada and written four full length musicals including<br />

The Winters Tale Project and Wedlocked: The Musical (both with Chris Wynters) and plays<br />

Myles, The HypoAllergenic Superhero and His Superhero Friends, Counting Americans (with<br />

Dave Horak) and has been published by the Playwrights Guild <strong>of</strong> Canada. She returned to<br />

Edmonton in 2002, where she became, and currently is, Co-Host <strong>of</strong> CityTV’s Breakfast<br />

Television.<br />

Bridget’s artistic relationship with Jason Carter began in 2008 when she curated his first solo<br />

art show Nanabozho: The Trickster Rabbit. She has since curated three more <strong>of</strong> his shows and<br />

then in 2001 Bridget and Jason wrote their first children’s book WHO IS BOO: THE CURIOUS<br />

TALES OF ONE TRICKSTER RABBIT. This book was launched at the Royal <strong>Alberta</strong> Museum<br />

in Edmonton, <strong>Alberta</strong>, where thousands <strong>of</strong> children took in the show over it’s 3 month run. The<br />

book is currently being developed into a Children’s Television series as well as, working with a<br />

writing team from NYC, being developed into full scale musical premiering Fall 2014. In the<br />

winter <strong>of</strong> 2012 Bridget and Jason opened up The Carter-Ryan <strong>Gallery</strong> and Live <strong>Art</strong> Venue in<br />

Canmore <strong>Alberta</strong> on Main Street, a place where art and live performance exist happily under<br />

the same ro<strong>of</strong>. Jason Carter and Bridget Ryan continue a prolific and exciting partnership with<br />

Rabbit In The Yard Productions, a multi-media production company that produces short films,<br />

promotional videos as well as music videos. In 2010 Bridget was named Woman <strong>of</strong> the Year by<br />

the Consumer Choice Awards in Edmonton.<br />

ABOUT BOO<br />

Who Is Boo: The Terrific Tales <strong>of</strong> One Trickster Rabbit is a 66-page illustrated children’s book<br />

written by Bridget Ryan and illustrated by Jason Carter that chronicles a perpetually curious<br />

rabbit who is in a continual race around the world with his brother, because ‘frankly, they forgot<br />

where they put the finish line’! Along the way Boo meets many animals. This fleet-footed rabbit,<br />

‘Boo’, inspired by Nanabozho, a trickster figure in Ojibwe mythology, is about curiosity that leads<br />

to wonderment that leads to helpfulness! In a world that runs the risk <strong>of</strong> become more<br />

disconnected (even though there is an abundance <strong>of</strong> social networking), it’s about stopping,<br />

connecting, and helping those we meet on our way. Watch out for the The Book <strong>of</strong> Boo: The<br />

Continued Tales <strong>of</strong> That Trickster Rabbit.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist and Curator Biographies/Statements<br />

Cover and book pages from Who is Boo? The Terrific Tales <strong>of</strong> One Trickster Rabbit, written<br />

by Bridget Ryan and iIllustrated by Jason Carter. Published in 2011, this first book by Ryan and<br />

Carter tells the story <strong>of</strong> one hilarious rabbit named Boo. In a constant race around the world with<br />

his Brother, Boo meets some curious characters and helps them solve a multitude <strong>of</strong> issues. As<br />

described by the artists, ‘Boo’s race around the world has no end, only adventures!’ The story<br />

and illustrations were inspired by Nanabozho and Trickster characters everywhere.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist and Curator Biographies/Statements<br />

Jaret Sinclair-Gibson<br />

Jaret Sinclair-Gibson is a Métis artist from Slave Lake, <strong>Alberta</strong> who now makes Edmonton his<br />

home. In 1999, he opened Sun & Moon Visionaries Aboriginal <strong>Art</strong>isan <strong>Gallery</strong> & Studio with the<br />

assistance <strong>of</strong> nine other Aboriginal artists. As a founding member <strong>of</strong> this Aboriginal-owned and<br />

operated business, Jaret has worked hard to build a staff base <strong>of</strong> 10 art administrators, artist<br />

instructors, and Elders, <strong>of</strong>fering art and traditional cultural programming to Edmonton’s<br />

Aboriginal youth, families, schools and community agencies, as well as hosting numerous art<br />

receptions, shows and exhibits in support <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong>’s Aboriginal artists and artisans.<br />

Jaret has served two terms as the Youth Representative on the Board <strong>of</strong> the Canadian Native<br />

Friendship Centre, three years on the <strong>Alberta</strong> Friendship Centre Association Youth Council and<br />

one year as the National Association <strong>of</strong> Friendship Centre - <strong>Alberta</strong> Representative. Jaret’s<br />

service to his community has earned him many accolades including the Aboriginal Role Models<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong> <strong>Art</strong> Award in 2008.<br />

Sun & Moon Visionaries Aboriginal <strong>Art</strong>isans Society<br />

Sun & Moon Visionaries is a not-for-pr<strong>of</strong>it organization that has been delivering successful<br />

community-based arts and culture programming to urban Aboriginal youth and artisans since<br />

1999. It is a sacred space in which to receive traditional ancestral teachings and to create<br />

opportunities for the intergenerational sharing <strong>of</strong> knowledge, wisdom and culture, as well as a<br />

place for self expression and participation in cultural ceremonies.<br />

Sun & Moon Visionaries is commitment to supporting the growth and development <strong>of</strong><br />

Aboriginal art and artists in <strong>Alberta</strong>, with specific emphasis on providing Aboriginal youth, artists<br />

and artisans with opportunities to develop as pr<strong>of</strong>essional artists, recognized for their cultural<br />

knowledge, artistic skills and performance abilities.<br />

We believe in the importance <strong>of</strong> culturally relevant and appropriate barrier-free programming that<br />

addresses issues <strong>of</strong> peer mentoring, role modelling, traditional leadership training, and one-onone<br />

support. Our programs include the Aboriginal Cultural <strong>Art</strong> Development Program for<br />

Emerging <strong>Art</strong>ists, the Sacred Self Master <strong>Art</strong>ists Mentoring Program, the Sacred Self Visual <strong>Art</strong><br />

Training Series, Music Recording and Mentorship.<br />

The intent <strong>of</strong> all Sun & Moon Visionaries programming is to improve the economic, social and<br />

personal prospects <strong>of</strong> urban Aboriginal youth and artisans, to provide accessible, communitybased,<br />

culturally relevant support to our urban Aboriginal community, as well as to honour the<br />

voices <strong>of</strong> our Elders, youth and artisan community.<br />

Jaret Sinclair-Gibson<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

An interview with Jason Carter<br />

According to Jason Carter, art ‘chose’ him. While he took art in high school, it wasn’t until<br />

many years after graduation that he became really aware <strong>of</strong> his artistic gifts. One year he was<br />

given a piece <strong>of</strong> soapsone for Christmas and one night, years later, he picked it up and carved a<br />

raven...and he has never stopped working since.<br />

Carter focused on carving for three to four years when, in preparation for an exhibition <strong>of</strong> his<br />

carvings at Sun and Moon Visionaries: Aboriginal <strong>Art</strong>ists Society in Edmonton, he decided to do<br />

some paintings based on his sculptural work as he felt he needed something on the wall. His<br />

painting career has evolved from this first step and has also led to literary works, such as the<br />

children’s book Who is Boo? The Terrific Tales <strong>of</strong> one Trickster Rabbit, created in collaboration<br />

with Bridget Ryan.<br />

While raised in urban environments, Carter has always been drawn to the subject <strong>of</strong> rabbits and<br />

to nature. For the artist, art is a way to learn about what he doesn’t know - such as the natural<br />

world - and a means to teach himself the ‘process <strong>of</strong> doing’.<br />

Carter explains that his art style fits into the mold <strong>of</strong> aboriginal art and the Euro-American art<br />

styles <strong>of</strong> abstraction and Pop <strong>Art</strong>. He has always been drawn to blocks <strong>of</strong> colour, even as an<br />

art student in school, and this concern is readily apparent in his work. In his colour choices he<br />

swings between personal taste and symbolic uses. In the paintings concerning rabbits in the<br />

exhibition <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Animals</strong>, for example, Carter uses orange because it is his favorite colour<br />

and rabbits his favourite animal. For the prairie dog works, on the other hand, the yellow is<br />

symbolic <strong>of</strong> wheat fields where prairie dogs can be found.<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Rabbit, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

In describing his Pop <strong>Art</strong> and Modernist sensibilities and his artistic intent in the series <strong>of</strong> works<br />

created for the exhibition <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Animals</strong> Carter states<br />

I paint because I love colour, simply love it. The feeling, the emotion that one can get just from<br />

standing next to a large canvas that is painted in a rather brilliant colour, like an orange or a<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

An interview with Jason Carter<br />

red, is unparalleled in my opinion. We underestimate the power <strong>of</strong> colour. As a result, I try and<br />

minimize anything that might get in the way <strong>of</strong> colour, like an image; an image <strong>of</strong> an animal for<br />

example. Some people refer to it as the use <strong>of</strong> ‘negative space’- I find that term to be rather<br />

ironic, considering I feel such positivity coming from the colour. When I create a piece, I am<br />

aware that the image in the painting and the colour share the canvas. I hope people take in the<br />

colour <strong>of</strong> the piece as much as they take in the image on the colour, because in my opinion, they<br />

are one in the same. The Rabbit on Orange. The Beaver on Green. The Moose on Grey. The<br />

colour in each one <strong>of</strong> these paintings plays just as much <strong>of</strong> a part as the ‘character’ in the<br />

painting when experiencing the piece. The designs in the paintings are actually inspired by my<br />

carvings. I try and use the least amount <strong>of</strong> lines to convey and conjure the image, trying to find<br />

‘the essence’ <strong>of</strong> the animal.<br />

I love this series (‘<strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Animals</strong>) for the simple fact that it takes the ‘audience’ on a very clear<br />

journey as to what once ‘was’ to what it now ‘is’. You see a beaver on green. All you are aware<br />

<strong>of</strong> is the Beaver. You can consider the beaver: take in the beaver tail, it’s teeth and see the<br />

beaver, by it’s home, near the river. Finally though, the third painting in each series gives you a<br />

different perspective - the beaver is still there, but just by a much different ‘home’ and certainly<br />

not one belonging to the beaver. My hope is that it creates an awareness in the ‘audience’ that<br />

we are truly on a shared land and to value it as such. It’s not so much the evolution <strong>of</strong> the<br />

animal in this series <strong>of</strong> triptics, but rather the evolution <strong>of</strong> man on the animals’ land. It is my hope<br />

that we can begin that discussion. How common it is for highways and roads to have animals<br />

beside it - we point from our cars and yell ‘get outta the way!!!” But if a prairie dog could speak,<br />

the dialogue it might have with speeding vehicles through the prairies. Consider what a mother<br />

bear with her cub might say to all the developers encroaching upon their forests and mountains.<br />

Development is inevitable, but awareness is key in creating consideration and a certain<br />

‘mindfullness’ when sharing this land. I truly hope this series gives pause to celebrate the ‘paws’<br />

that went before us!<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Talking <strong>Art</strong><br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Wolf and Moon, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

CONTENTS:<br />

- Curriculum Connections<br />

- <strong>Animals</strong> in Mythology and Symbolism: A Survey<br />

- <strong>Animals</strong>/Birds: First Nations Beliefs and Stories<br />

Scientific Studies:<br />

Bear<br />

Beaver<br />

Moose<br />

Prairie Dog<br />

Rabbit<br />

Wolf<br />

- <strong>Animals</strong> in <strong>Art</strong>/<strong>Art</strong> Styles - Abstraction/The History <strong>of</strong> Abstraction<br />

- Modernism<br />

- Post-painterly Abstraction<br />

- Colour Field Painting<br />

- Pop <strong>Art</strong><br />

- Postmodernism in <strong>Art</strong><br />

- The Woodland Style<br />

- <strong>Animals</strong> in <strong>Alberta</strong> <strong>Art</strong>: A Survey<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Curriculum Connections<br />

The following curricular connections taken from the <strong>Alberta</strong> Learning Program <strong>of</strong> Studies<br />

provide a brief overview <strong>of</strong> the key topics that can be addressed through viewing and<br />

discussing the exhibition <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Animals</strong>. Through the art projects included in this<br />

exhibition guide students will be provided the opportunity for a variety <strong>of</strong> learning<br />

experiences.<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Connections K-6<br />

REFLECTION<br />

Students will notice commonalities within classes <strong>of</strong> natural objects or forms.<br />

i. Natural forms have common physical attributes according to the class in which they belong.<br />

ii. Natural forms are related to the environment from which they originate.<br />

iii. Natural forms have different surface qualities in colour, texture and tone.<br />

iv. Natural forms display patterns and make patterns.<br />

DEPICTION<br />

Students will perfect forms and develop more realistic treatments.<br />

i. Images can be portrayed in varying degrees <strong>of</strong> realism.<br />

Students will learn the shapes <strong>of</strong> things as well as develop decorative styles.<br />

i. <strong>Animals</strong> and plants can be represented in terms <strong>of</strong> their proportions.<br />

Students will increase the range <strong>of</strong> actions and viewpoints depicted.<br />

Students will represent and refine surface qualities <strong>of</strong> objects or forms.<br />

i. Texture is a surface quality that can be captured by rubbings or markings.<br />

ii. Colour can be lightened to make tints or darkened to make shades.<br />

iii. Gradations <strong>of</strong> tone are useful to show depth or the effect <strong>of</strong> light on objects.<br />

iv. By increasing details in the foreground the illusion <strong>of</strong> depth and reality can be enhanced.<br />

COMPOSITION<br />

Students will create unity through density and rhythm.<br />

i. Families <strong>of</strong> shapes, and shapes inside or beside shapes, create harmony.<br />

ii. Overlapping forms help to unify a composition.<br />

iii. Repetition <strong>of</strong> qualities such as colour, texture and tone produce rhythm and balance.<br />

EXPRESSION<br />

Students will use media and techniques, with an emphasis on exploration and direct methods in<br />

drawing, painting, printmaking, sculpture, fabric arts, photography and technographic arts.<br />

i. Use a variety <strong>of</strong> drawing media in an exploratory way to see how each one has its own<br />

characteristics. Use frottage (texture rubbings).<br />

Students will decorate items personally created.<br />

i. Details, patterns or textures can be added to two-dimensional works.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Curriculum Connections continued<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Connections 7-9<br />

DRAWING<br />

Students will examine and simplify basic shapes and spaces.<br />

i. Shapes may be organic or geometric.<br />

ii. Geometric and organic shapes can be used to create positive and negative spaces.<br />

Students will employ space, proportion and relationships for image making.<br />

i. The size <strong>of</strong> depicted figures or objects locates those objects in relationship to the ground or<br />

picture plane.<br />

ii. Overlapping figures or objects create an illusion <strong>of</strong> space in two-dimensional works.<br />

iii. The amount <strong>of</strong> detail depicted creates spatial depth in two-dimensional works.<br />

iv. Proportion can be analyzed by using a basic unit <strong>of</strong> a subject as a measuring tool.<br />

COMPOSITION<br />

Students will experiment with value, light, atmosphere and colour selection to reflect mood in<br />

composition.<br />

i. Mood in composition can be affected by proximity or similarity <strong>of</strong> selected figures or units.<br />

ii. Mood in composition can be enhanced by the intensity <strong>of</strong> the light source and the value <strong>of</strong> the<br />

rendered shading.<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

Students will consider the natural environment as a source <strong>of</strong> imagery through time and across<br />

cultures.<br />

i. Images <strong>of</strong> nature change through time and across cultures.<br />

Students will identify similarities and differences in expressions <strong>of</strong> selected cultural groups.<br />

i. Symbolic meanings are expressed in different ways by different cultural groups.<br />

ART CONNECTIONS 10-20-30<br />

DRAWINGS<br />

Students will develop and refine drawing skills and styles.<br />

i. Control <strong>of</strong> proportion and perspective enhances the realism <strong>of</strong> subject matter in drawing.<br />

COMPOSITIONS<br />

Students will use the vocabulary and techniques <strong>of</strong> art criticism to analyze and evaluate their<br />

own works in relation to the works <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional artists.<br />

i. Criteria such as originality, organization, technique, function and clarity <strong>of</strong> meaning may be<br />

applied in evaluating works <strong>of</strong> art.<br />

ii. <strong>Art</strong>works may be analyzed for personal, social, historic or artistic significance.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Curriculum Connections continued<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

Students will investigate the process <strong>of</strong> abstracting from a source in order to create objects and<br />

images.<br />

i. <strong>Art</strong>ists simplify, exaggerate and rearrange parts <strong>of</strong> objects in their depictions <strong>of</strong> images.<br />

Students will recognize that while the sources <strong>of</strong> images are universal, the formation <strong>of</strong> an<br />

image is influenced by the artist’s choice <strong>of</strong> medium, the time and the culture.<br />

i. Different periods <strong>of</strong> history yield different interpretations <strong>of</strong> the same subject or theme.<br />

ii. <strong>Art</strong>ists and craftspeople use the possibilities and limitations <strong>of</strong> different materials to develop<br />

imagery.<br />

iii. Different cultures exhibit different preferences for forms, colours and materials in their<br />

artifacts.<br />

This exhibition is an excellent source for using art as a means <strong>of</strong> investigating topics<br />

addressed in other subject areas. The theme <strong>of</strong> the exhibition, and the works within it,<br />

are especially relevant as a spring-board for addressing aspects <strong>of</strong> the Science and<br />

Language <strong>Art</strong>s program <strong>of</strong> studies. The following is an overview <strong>of</strong> cross-curricular<br />

connections which may be addressed through viewing and discussing the exhibition.<br />

ELEMENTARY SCIENCE<br />

1–5 Students will identify and evaluate methods for creating colour and for applying colours to<br />

different materials.<br />

i. Identify colours in a variety <strong>of</strong> natural and manufactured objects.<br />

ii. Compare and contrast colours, using terms such as lighter than, darker than, more blue,<br />

brighter than.<br />

iii. Order a group <strong>of</strong> coloured objects, based on a given colour criterion.<br />

iv. Predict and describe changes in colour that result from the mixing <strong>of</strong> primary colours and<br />

from mixing a primary colour with white or with black.<br />

v. Create a colour that matches a given sample, by mixing the appropriate amounts <strong>of</strong> two<br />

primary colours.<br />

vi. Distinguish colours that are transparent from those that are not. Students should recognize<br />

that some coloured liquids and gels can be seen through and are thus transparent and that<br />

other colours are opaque.<br />

vii. Compare the effect <strong>of</strong> different thicknesses <strong>of</strong> paint. Students should recognize that a very<br />

thin layer <strong>of</strong> paint, or a paint that has been watered down, may be partly transparent.<br />

viii. Compare the adherence <strong>of</strong> a paint to different surfaces; e.g., different forms <strong>of</strong> papers,<br />

fabrics and plastics.<br />

1–11 Describe some common living things, and identify needs <strong>of</strong> those living things.<br />

3–10 Describe the appearances and life cycles <strong>of</strong> some common animals, and identify their<br />

adaptations to different environments.<br />

6.10 Describe kinds <strong>of</strong> plants and animals found living on, under and among trees; and identify<br />

how trees affect and are affected by those living things as part <strong>of</strong> a forest ecosystem.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Curriculum Connections continued<br />

JUNI0R HIGH SCIENCE<br />

SCIENCE 7 Unit A: Interactions and Ecosystems<br />

Students will:<br />

1. Investigate and describe relationships between humans and their environments<br />

- describe examples <strong>of</strong> interaction and interdependency within an ecosystem<br />

- identify example <strong>of</strong> human impacts on ecosystems, and investigate and analyze the link<br />

between these impacts and the human wants and needs that give rise to them<br />

- analyze personal and public decisions that involve consideration <strong>of</strong> environmental impacts,<br />

and identfy needs for scientific knowledge that can inform those decisions<br />

2. Trace and interpret the flow <strong>of</strong> energy and materials within an ecosystem<br />

- analyze ecosystems to identify producers, consumers, and decomposers; and describe how<br />

energy is supplied to and flows through a food web<br />

3. Monitor a local environment and assess the impacts <strong>of</strong> environmental factors on the growth,<br />

health and reproduction <strong>of</strong> organisms in that environment<br />

- investigate a variety <strong>of</strong> habitats, and describe and interpret distribution patterns <strong>of</strong> living things<br />

found in those habitats<br />

- investigate and intepret evidence <strong>of</strong> interaction and change<br />

4. Describe the relationship among knowledge, decisions and actions in maintaining<br />

life-supporting environments<br />

- identify intended and unintended consequences <strong>of</strong> human activities within local and global<br />

environments<br />

SCIENCE 9<br />

Biological Diversity: Students will:<br />

–Investigate and interpret diversity among species and within species, and describe how<br />

diversity contributes to species survival.<br />

–Identify impacts <strong>of</strong> human action on species survival and variation within species, and analyze<br />

related issues for personal and public decision making.<br />

–Describe ongoing changes in biological diversity through extinction and extirpation <strong>of</strong> native<br />

species, and investigate the role <strong>of</strong> environmental factors in causing these changes. (e.g.,<br />

investigate the effect <strong>of</strong> changing land use on the survival <strong>of</strong> wolf or grizzly bear populations).<br />

BIOLOGY 20<br />

Students will explain the mechanisms involved in the change <strong>of</strong> populations over time.<br />

LANGUAGE ARTS<br />

K.4.3 Students will use drawings to illustrate ideas and information and talk about them.<br />

5.2.2 Experience oral, print and other media texts from a variety <strong>of</strong> cultural traditions and<br />

genres, such as historical fiction, myths, biographies, and poetry.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Curriculum Connections continued<br />

6.4.3 Demonstrate attentive listening and viewing. Students will identify the tone, mood and<br />

emotion conveyed in oral and visual presentations.<br />

9.2.2 Discuss how techniques, such as irony, symbolism, perspective and proportion,<br />

communicate meaning and enhance effect in oral, print and other media texts.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> in Mythology and Symbolism<br />

The bond between humans and animals is as old as<br />

humankind itself. Until the development <strong>of</strong> agriculture<br />

around 10,000 years ago, animals were the primary<br />

source <strong>of</strong> both food and clothing for humans and<br />

maintained this standing for hunting and gathering<br />

societies around the world up until the nineteenth<br />

century. The economic importance <strong>of</strong> animals to humans<br />

was accompanied by the accordance <strong>of</strong> spiritual and<br />

ceremonial significance to many creatures and both<br />

the economic and sacred importance <strong>of</strong> animals were<br />

recorded visually very early in human history.<br />

George Weber<br />

Petroglyphs, Writing on Stone, <strong>Alberta</strong>,<br />

1963<br />

Silkscreen<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong><br />

Horse Painting, 17,000 years B.P.<br />

Lascaux Cave, Lascaux, France<br />

Since the beginning <strong>of</strong> time humans have developed myths and<br />

legends about animals and these stories have been expressed<br />

in both visual and literal works.<br />

In many myths animals were manifestations <strong>of</strong> divine power and<br />

the gods could take on animal form. The ancient Egyptians, for<br />

example, portrayed their gods as animals or as humans with the<br />

heads <strong>of</strong> animals. The God Horus, ancient Egypt’s national patron<br />

and God <strong>of</strong> the sky, war, and god <strong>of</strong> protection, for example, is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

portrayed with the body <strong>of</strong> a man and the head <strong>of</strong> a falcon. A second<br />

and very important god in the Egyptian pantheon which shared this<br />

duality is the God Anubis. Anubis was the jackal-headed God<br />

associated with mummification and the protection <strong>of</strong> the dead in their<br />

journey to the afterlife.<br />

Horus, Standing<br />

http://en.ciwkipedia.org/wiki/<br />

Egyptian_gods<br />

Anubis attending the mummy<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sennendjem<br />

http://en.ciwkipedia.org/wiki/<br />

Anubis<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> in Mythology and Symbolism<br />

continued<br />

In Greek and Roman myths the Gods could transform into animals in order to interact<br />

with humans. This is seen, for example, in the myth <strong>of</strong> Leda and the swan. According to this<br />

myth Zeus, King <strong>of</strong> the Gods, transformed into a swan in order to seduce the mortal queen Leda.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the children <strong>of</strong> their union was Helen <strong>of</strong> Troy, the most beautiful woman on earth. All<br />

mythological tricksters - such as the Norse God Loki or the Native American Coyote - also<br />

possessed this shape-shifting ability. <strong>Animals</strong> also functioned as symbols <strong>of</strong> the dieties. Owls,<br />

for example, were traditionally associated with wisdom. In Greek myths Athena, the goddess <strong>of</strong><br />

wisdom, is <strong>of</strong>ten portrayed with an owl.<br />

Leda and the Swan<br />

(Copy after Michelangelo)<br />

National <strong>Gallery</strong>, London<br />

image credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/<br />

Leda_and_the_Swan<br />

Paul Cezanne<br />

Leda and the Swan, 1880-1882(?)<br />

Barnes Foundation Collection<br />

Merion, Pennsylvania<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> are ascribed a variety <strong>of</strong> roles in the<br />

world’s mythologies. Many explain the part<br />

that animals played in creating the world or in<br />

bringing fire, tools, or farming skills to humans.<br />

In Asian and many Native North American<br />

traditions, for example, the earth is situated on<br />

the back <strong>of</strong> an enormous turtle. <strong>Animals</strong> are<br />

also linked to the creation <strong>of</strong> human beings. In<br />

Haida mythology the Raven found and freed<br />

some creatures trapped in a clam shell and<br />

these scared and timid beings were the first<br />

men. Raven later found and freed some female<br />

beings trapped in a mollusc and then brought<br />

the two sexes together.<br />

Bill Reid<br />

Raven and the First Men,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> British Columbia<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Anthropology<br />

Vancouver, BC<br />

image credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_<br />

Reid<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> in Mythology and Symbolism<br />

continued<br />

Many Native American groups also believed that they were descended from a particular<br />

animal. This animal became the groups totem and a powerful symbol <strong>of</strong> its identity. Many also<br />

believe that each person has a magical or spiritual connection to a particular animal that can act<br />

as a guardian, a source <strong>of</strong> wisdom, or an inspiration. <strong>Animals</strong> also helped shape human<br />

existence by acting as messengers to the gods.<br />

During the Middle Ages animals were an essential aspect <strong>of</strong> almost every facet <strong>of</strong> life.<br />

They formed the back-bone <strong>of</strong> an agrarian economy, served as instantly recognized visual<br />

symbols, and were imagined to be the fantastic inhabitants <strong>of</strong> unknown realms. In Christian art<br />

animals always occupied a place <strong>of</strong> great importance and representations <strong>of</strong> real and imagined<br />

beasts were found in monumental sculpture, illuminated manuscripts, tapestries, and stained<br />

glass windows. With the beginning <strong>of</strong> the thirteenth century, Gothic art affords the greatest<br />

number and best representations <strong>of</strong> animal forms. During this period ‘bestiaries’, popular<br />

treatises on natural history, were fully illustrated in the sculptural work in the great cathedrals.<br />

Medieval Manuscript Page<br />

Medieval Tapestry examples (Lion and Unicorn)<br />

The Cloisters<br />

Metropolitan Museum <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

New York, New York<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> were either used as purely decorative elements in medieval artwork or served<br />

symbolic functions. Many Catholic saints, for example, are illustrated with animals that<br />

accompany them and represent certain <strong>of</strong> the saint’s qualities or aspects <strong>of</strong> the saint’s story. St.<br />

Hubert, for example, is <strong>of</strong>ten portrayed with a stag as, according to his story, it was an<br />

encounter with a stag with a crucifix between its antlers which led to his conversion to<br />

Christianity. St. Jerome, the great teacher <strong>of</strong> the early Church, is <strong>of</strong>ten portrayed with a lion,<br />

based on the story that he removed a thorn from its paw. The lion, in gratitude, remained<br />

Jerome’s faithful companion for the rest <strong>of</strong> its life.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> in Mythology and Symbolism<br />

continued<br />

In both Christian and Native North American sources, animals were ascribed a number <strong>of</strong><br />

symbolic meanings. Among these are:<br />

Antelope - action<br />

Bear - strength, dreaming, introspection, power and protection, leadership<br />

Buffalo - prayer, abundance, survival needs, good fortune, healing<br />

Elephant - commitment, strength, astuteness<br />

Elk - stamina, pride, power, majesty, freedom<br />

Fox - cunning, intelligence, tricksters, shape-shifters<br />

Frog - symbolizes renewal, fertility and springtime; healing, health, honesty, purification. Also a<br />

guardian symbol: when strangers approached the croaking <strong>of</strong> the frog would serve as a warning.<br />

Giraffe - grounded vision<br />

Moose - self esteem and assertiveness<br />

Mountain Lion/Cougar - wisdom, leadership, swiftness<br />

Owl - deception, wisdom, clairvoyance, magic. Some Native American groups perceive the owl<br />

as a harbringer <strong>of</strong> death, while others see owls as guardians <strong>of</strong> both the home and the village.<br />

Rabbit - fear, fertility, magic, speed, swiftness, longevity<br />

Deer - graceful gentleness, sensitivity, compassion, kindness<br />

Wolf - teacher, A guide to the sacred<br />

Zebra - individuality<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> in Mythology and Symbolism<br />

continued<br />

While animal iconography was extremely important in the early middle ages, by the 14th<br />

century the use <strong>of</strong> animals in art had become less frequent. In the fifteenth and sixteenth<br />

centuries animals were drawn more closely from life without any intention <strong>of</strong> symbolism and, by<br />

the Renaissance, they were nearly banished from visual representation except as an accessory<br />

to the human figure.<br />

Animal Images from the collection <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong><br />

Parr<br />

Untitled, 1962<br />

Wax Crayon on paper<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong><br />

Pierre Dorian<br />

Galleria Corsini (Prometheus), 1995<br />

Oil on linen<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong><br />

Paul Nash<br />

The Fish and Fowl (Genesis), 1924<br />

Wood engraving<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alberta</strong><br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

Jason Carter<br />

The Moose, 2012<br />

Acrylic on canvas<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> the artist<br />

<strong>Animals</strong><br />

First Nations<br />

Beliefs and Stories<br />

and Scientific Studies<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

First Nations Beliefs<br />

As Aboriginal People we hold all life forms in great respect, understanding that each<br />

animal has a physical presence, a spiritual power and a life purpose. We believe that all<br />

life is interconnected and all beings are reliant on each other.<br />

First Nations Perspective <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Animals</strong>:<br />

Beaver:<br />

Moose:<br />

Bear:<br />

Prairie Dog:<br />

Respected as a hard worker, it was good to have a family <strong>of</strong> beavers near<br />

the community. Beavers kept the eco-system and wetlands healthy and<br />

vibrant, which in turn helped to provide a balanced landscape for an<br />

abundant harvest <strong>of</strong> medicines.<br />

Eaters <strong>of</strong> the willow, moose meat was rich with the bitter medicine. Like<br />

the buffalo, the moose provided the people with hide, meat, everything<br />

needed to live and survive, to this day. Buffalo was migratory, but the<br />

moose lived year round in bush country. The good waterways created by<br />

the beaver kept the moose nearby and thriving.<br />

Powerful with a real strong spirit, the Bear gave the people medicines.<br />

The bear had more natural power and knowledge. When you went to hunt<br />

the bear you would pray and give thanks for his sacrifice. The bear was a<br />

teacher <strong>of</strong> the medicines. The people would pray and ask the bear for help<br />

to find the bear root heart medicine and to show us where the berries were<br />

that were healthy to eat.<br />

When times were hard, the prairie dog kept the people fed. They were the<br />

root diggers, with their own medicines, teaching the people to live<br />

harmoniously together, such as they did within a communal society.<br />

All animals have lessons to teach us. Each animal has a life, has spirit, has a purpose, so when<br />

we had to kill one for food, we asked respectfully and with gratitude for their life.<br />

Mother Earth and all its beings are equal. The Human Race expects and deserves equal rights,<br />

so let us give the same respect to natures’ animals, and with understanding, harmoniously<br />

share our urban environment, seeing the nature amongst us as a gift that enriches and blesses<br />

all <strong>of</strong> us.<br />

Jaret Sinclair-Gibson<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

First Nations Beliefs continued<br />

Canada’s First Nations peoples value a history <strong>of</strong> oral tradition that accounts for each<br />

group’s origins, history, spirituality, lessons <strong>of</strong> morality and life skills. Stories bind a<br />

community with its past and future and oral traditions are passed from generation to<br />

generation.<br />

Native religions developed from anthropomorphism and animism philosophies. <strong>Animals</strong>,<br />

plants, trees, and inanimate objects are interpreted in human terms and their relation<br />

to the earth, sky and water. A cosmological order exists, within which humans live, that<br />

values balance and harmony with all <strong>of</strong> these forces. While the stories differ from tribe to<br />

tribe, all have stories concerning the origins <strong>of</strong> life on earth, the roles played by various<br />

life forms, and the relationships between humans, animals, and other life forms.<br />

Bear is a strong Native American symbol. Native American groups regarded the grizzly bear<br />

with awe and respect and the bear is a pr<strong>of</strong>ound symbol <strong>of</strong> majesty, freedom and power. Some<br />

tribes, such as the Cree, adopted the bear as a symbol <strong>of</strong> successful hunting due to its girth and<br />

amazingly effective teeth and claws. Symbolic traits associated with the bear include:<br />

- protection<br />

- childbearing<br />

- motherhood<br />

- freedom<br />

- discernment<br />

- courage<br />

- power<br />

- unpredictability<br />

Rabbit is a symbol in many differenct cultures <strong>of</strong> the world. Native American groups<br />

regarded the rabbit as a trickster. Natives have a special character known as Nanabozho. This is<br />

the character <strong>of</strong> the Great Hare and is considered to be a very powerful mythological character<br />

with many legends associated with it. Some tribes looked upon Nanabozho as a hero and even<br />

consider the Great Hare to be the creator <strong>of</strong> the Earth. Nanabozho is also regarded as being<br />

a supporter <strong>of</strong> humans and helps them out in many ways such as bringing fire and light. Some<br />

groups also believed that the Great Hare taught sacred rituals to the holy men amongst the<br />

Natives. In some tribes, however, Nanabozho is depicted as a clown, a predator and even a<br />

thief. Symbolic traits associated with the rabbit include:<br />

- fear<br />

- overcoming limiting beliefs<br />

- fear caller - the rabbit calls upon himself the things he fears the most<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

First Nations Beliefs continued<br />

Wolf Wolves figure prominently in the mythology <strong>of</strong> nearly every Native American tribe.<br />

Many North American tribes considered wolves closely related to humans and the origin stories<br />

<strong>of</strong> some Northwest Coast tribes tell <strong>of</strong> their first ancestors being transformed from wolves into<br />

men. In some cultures, such as the Shoshone, Wolf plays the orle <strong>of</strong> the noble Creator god,<br />

while in Anishinabe mythology a wolf character is the brother and true best friend <strong>of</strong> the culture<br />

hero. Symbolic traits associated with the wolf include:<br />

- courage<br />

- strength<br />

- loyalty<br />

- success in hunting<br />

- teacher <strong>of</strong> new ideas and wisdom<br />

- teaches cooperation, protectiveness and the value <strong>of</strong> extended families<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

First Nations Stories<br />

A Story about the Bear - How Bear Lost His Tail<br />

Back in the old days, Bear had a tail which was his proudest possession. It was long and black<br />

and glossy and Bear used to wave it around just so that people would look at it. Fox saw this.<br />

Fox, as everyone knows, is a trickster and likes nothing better than fooling others. So it was that<br />

he decided to play a trick on Bear.<br />

It was the time <strong>of</strong> year when Hatho, the Spirit <strong>of</strong> Frost, had swept across the land, covering<br />

the lakes with ice and pounding on the trees with his big hammer. Fox made a hole in the ice,<br />

right near a place where Bear liked to walk. By the time Bear came by, all around Fox, in a big<br />

circle, were big trout and fat perch. Just as Bear was about to ask Fox what he was doing, Fox<br />

twitched his tail which he had sticking through that hole in the ice and pulled out a huge trout.<br />

‘Greetings, Brother,’ said Fox. ‘How are you this fine day?’<br />

‘Greetings,’ answered Bear, looking at the big circle <strong>of</strong> fat fish. ‘I am well, Brother. But what are<br />

you doing?’<br />

‘I am fishing,’ answered Fox. ‘Would you like to try?’<br />

‘Oh, yes,’ said Bear, as he started to lumber over to Fox’s fishing hole.<br />

But Fox stopped him. ‘Wait, Brother,’ he said, ‘This place will not be good. As you can see, I<br />

have already caught all the fish. Let us make you a new fishing spot where you can catch many<br />

big trout.’<br />

Bear agreed and so he followed Fox to the new place, a place where, as Fox knew very well,<br />

the lake was too shallow to catch the winter fish - which always stay in the deepest water when<br />

Hatho has covered their ponds. Bear watched as Fox made the hole in the ice, already<br />

tasting the fine fish he would soon catch. ‘Now,’ Fox said, ‘you must do just as I tell you. Clear<br />

your mind <strong>of</strong> all thoughts <strong>of</strong> fish. Do not even think <strong>of</strong> a song or the fish will hear you. Turn your<br />

back to the hole and place your tail inside it. Soon a fish will come and grab your tail and you<br />

can pull him out.’<br />

‘But how will I know if a fish has grabbed my tail if my back is turned?’ asked Bear.<br />

‘I will hide over here where the fish cannot see me,’ said Fox. ‘ When a fish grabs your tail, I will<br />

shout. Then you must pull as hard as you can to catch your fish. But you must be very patient.<br />

Do not move at all until I tell you.’<br />

Bear nodded, ‘I willl do exactly as you say.’ He sat down next to the hole, placed his long<br />

beautiful black tail in the icy water and turned his back.<br />

Fox watched for a time to make sure that Bear was doing as he was told and then, very quietly,<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

First Nations Stories continued<br />

sneaked back to his own house and went to bed. The next morning he woke up and thought <strong>of</strong><br />

Bear. ‘I wonder if he is still there,’ Fox said to himself. ‘I’ll just go and check.’<br />

So Fox went back to the ice covered pond and what do you think he saw? He saw what looked<br />

like a little white hill in the middle <strong>of</strong> the ice. It had snowed during the night and covered Bear,<br />

who had fallen asleep while waiting for Fox to tell him to pull his tail and catch a fish. And Bear<br />

was snoring. His snores were so loud that the ice was shaking. It was so funny that Fox rolled<br />

with laughter. But when he was through laughing, he decided the time had come to wake up<br />

poor Bear. He crept very close to Bear’s ear, took a deep breath, and then shouted: ‘Now,<br />

Bear!!!’<br />

Bear woke up with a start and pulled his long tail hard as he could. But his tail had been caught<br />

in the ice which had frozen over during the night and as he pulled, it broke <strong>of</strong>f -- Whack! -- just<br />

like that. Bear turned around to look at the fish he had caught and instead saw his long lovely tail<br />

caught in the ice.<br />

‘Phhh,’ he moaned ‘ohhh Fox. I will get you for this.’ But Fox, even though he was laughing fit to<br />

kill, was faster than Bear and he leaped aside and was gone.<br />

So it is that even to this day Bears have short tails and no love at all for Fox. And if you ever<br />

hear a bear moaning, it is probably because he remembers the trick Fox played on him long ago<br />

and he is mourning for his lost tail.<br />

AFA Travelling Exhibition Program, Edmonton, AB. Ph: 780.428.3830 Fax: 780.421.0479<br />

youraga.ca

The <strong>Alberta</strong> Foundation for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travelling Exhibition Program<br />

First Nations Stories continued<br />

A story about the Beaver - How the Beaver got his tail<br />

(An Ojibwa Legend)<br />

Once upon a time there was a beaver that loved to brag about his tail. One day while taking a<br />

walk, the beaver stopped to talk to a bird. The beaver said to the bird, “Don’t you love my fluffy<br />

tail?”<br />

“Why, yes I do little beaver” replied the bird.<br />

“Don’t you wish your feathers were as fluffy as my tail? Don’t you wish your feathers were as<br />

strong as my tail? Don’t you wish your feathers were just as beautiful as my tail?” the beaver<br />

asked.<br />

“Why do you think so much <strong>of</strong> your tail, little beaver?” asked the bird. This insulted the beaver<br />

and he walked away.<br />