Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals 2012 - World Health Organization

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals 2012 - World Health Organization

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals 2012 - World Health Organization

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

POPs such as PCBs and DDT were banned in<br />

many countries over 20 years ago due to their<br />

environmental persistence and toxicity. As a<br />

result, their levels in humans and wildlife have<br />

declined in recent decades. Bird populations<br />

exposed to high levels of DDT, and in particular<br />

to its persistent metabolite, DDE, in the 1950s<br />

through 1970s in North America and Europe are,<br />

since 1975, showing lower concentrations of DDT<br />

and DDE and clear signs of recovery (Figure 22).<br />

However, there are studies showing that current<br />

low levels of these persistent chemicals are still<br />

causing harm, because they or their breakdown<br />

products remain in the environment long after<br />

their use has been banned.<br />

Lead is an important example of the cost of<br />

inaction in the face of toxicity data. Lead has<br />

been a known neurotoxicant since the Roman<br />

times; nonetheless, it was used in gasoline and<br />

paint around the world. The impact of lead<br />

on children is profound, because it causes<br />

irreversible damage to developing bone and<br />

brain tissues. The most damaging impact resulted<br />

from the use of lead in gasoline, which caused an<br />

estimated intelligence quotient (IQ) loss of five<br />

points in millions of children worldwide.<br />

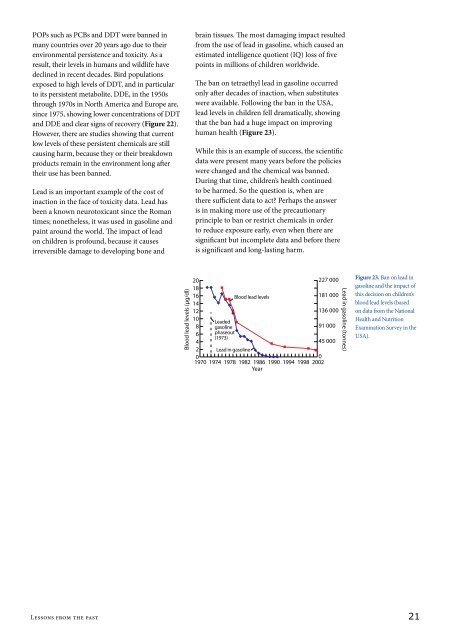

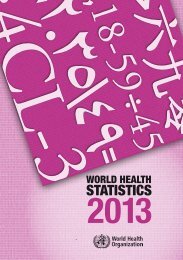

The ban on tetraethyl lead in gasoline occurred<br />

only after decades of inaction, when substitutes<br />

were available. Following the ban in the USA,<br />

lead levels in children fell dramatically, showing<br />

that the ban had a huge impact on improving<br />

human health (Figure 23).<br />

While this is an example of success, the scientific<br />

data were present many years before the policies<br />

were changed and the chemical was banned.<br />

During that time, children’s health continued<br />

to be harmed. So the question is, when are<br />

there sufficient data to act? Perhaps the answer<br />

is in making more use of the precautionary<br />

principle to ban or restrict chemicals in order<br />

to reduce exposure early, even when there are<br />

significant but incomplete data and before there<br />

is significant and long-lasting harm.<br />

Blood lead levels (μg/dl)<br />

20<br />

227 000<br />

18<br />

16<br />

Blood lead levels<br />

181 000<br />

14<br />

12<br />

136 000<br />

10<br />

Leaded<br />

8 gasoline<br />

91 000<br />

6 phaseout<br />

(1973)<br />

4<br />

45 000<br />

2 Lead in gasoline<br />

0<br />

0<br />

1970 1974 1978 1982 1986 1990 1994 1998 2002<br />

Year<br />

Lead in gasoline (tonnes)<br />

Figure 23. Ban on lead in<br />

gasoline and the impact of<br />

this decision on children’s<br />

blood lead levels (based<br />

on data from the National<br />

<strong>Health</strong> and Nutrition<br />

Examination Survey in the<br />

USA).<br />

Lessons from the past<br />

21