2013 PVM Report - Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine

2013 PVM Report - Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine

2013 PVM Report - Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Living with Lymphoma<br />

When the first <strong>Purdue</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> students started studying<br />

in Lynn Hall, “cancer research” was not thought <strong>of</strong> as something<br />

targeted at helping man’s best friend. But within 20 years, <strong>Purdue</strong><br />

<strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong> opted for a pioneering role in “comparative<br />

research,” realizing that studying and treating cancer in animals<br />

had the potential to help humans, and the <strong>Purdue</strong> Comparative<br />

Oncology Program (PCOP) was born in 1979. More than 30<br />

years later, the program continues to push the frontiers <strong>of</strong> cancer<br />

research while providing compassionate care for pets with cancer<br />

and training future specialists.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the PCOP research efforts underway today seeks<br />

to improve the outlook for dogs with lymphoma. Assistant<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Comparative Oncology Michael Childress says<br />

the term “lymphoma” is actually a misnomer, as there are more<br />

than 30 different types <strong>of</strong> lymphoma known to occur in the dog.<br />

Lymphomas account for nearly 15% <strong>of</strong> all canine cancers. The<br />

most common type <strong>of</strong> lymphoma is called “Diffuse Large B-Cell<br />

Lymphoma” (DLBCL), which typically is indicated by enlarged<br />

lymph nodes. Distributed at numerous sites throughout the<br />

body, lymph nodes are organs that function as part <strong>of</strong> the body’s<br />

immune system. DLBCL also can spread to affect other organs<br />

such as the spleen, liver, and bone marrow.<br />

Dr. Childress explains that the standard treatment for DLBCL<br />

11<br />

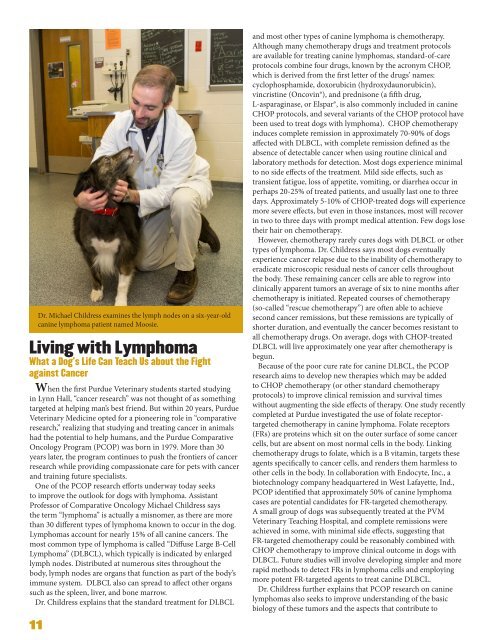

Dr. Michael Childress examines the lymph nodes on a six-year-old<br />

canine lymphoma patient named Moosie.<br />

What a Dog’s Life Can Teach Us about the Fight<br />

against Cancer<br />

and most other types <strong>of</strong> canine lymphoma is chemotherapy.<br />

Although many chemotherapy drugs and treatment protocols<br />

are available for treating canine lymphomas, standard-<strong>of</strong>-care<br />

protocols combine four drugs, known by the acronym CHOP,<br />

which is derived from the first letter <strong>of</strong> the drugs’ names:<br />

cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin (hydroxydaunorubicin),<br />

vincristine (Oncovin®), and prednisone (a fifth drug,<br />

L-asparaginase, or Elspar®, is also commonly included in canine<br />

CHOP protocols, and several variants <strong>of</strong> the CHOP protocol have<br />

been used to treat dogs with lymphoma). CHOP chemotherapy<br />

induces complete remission in approximately 70-90% <strong>of</strong> dogs<br />

affected with DLBCL, with complete remission defined as the<br />

absence <strong>of</strong> detectable cancer when using routine clinical and<br />

laboratory methods for detection. Most dogs experience minimal<br />

to no side effects <strong>of</strong> the treatment. Mild side effects, such as<br />

transient fatigue, loss <strong>of</strong> appetite, vomiting, or diarrhea occur in<br />

perhaps 20-25% <strong>of</strong> treated patients, and usually last one to three<br />

days. Approximately 5-10% <strong>of</strong> CHOP-treated dogs will experience<br />

more severe effects, but even in those instances, most will recover<br />

in two to three days with prompt medical attention. Few dogs lose<br />

their hair on chemotherapy.<br />

However, chemotherapy rarely cures dogs with DLBCL or other<br />

types <strong>of</strong> lymphoma. Dr. Childress says most dogs eventually<br />

experience cancer relapse due to the inability <strong>of</strong> chemotherapy to<br />

eradicate microscopic residual nests <strong>of</strong> cancer cells throughout<br />

the body. These remaining cancer cells are able to regrow into<br />

clinically apparent tumors an average <strong>of</strong> six to nine months after<br />

chemotherapy is initiated. Repeated courses <strong>of</strong> chemotherapy<br />

(so-called “rescue chemotherapy”) are <strong>of</strong>ten able to achieve<br />

second cancer remissions, but these remissions are typically <strong>of</strong><br />

shorter duration, and eventually the cancer becomes resistant to<br />

all chemotherapy drugs. On average, dogs with CHOP-treated<br />

DLBCL will live approximately one year after chemotherapy is<br />

begun.<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> the poor cure rate for canine DLBCL, the PCOP<br />

research aims to develop new therapies which may be added<br />

to CHOP chemotherapy (or other standard chemotherapy<br />

protocols) to improve clinical remission and survival times<br />

without augmenting the side effects <strong>of</strong> therapy. One study recently<br />

completed at <strong>Purdue</strong> investigated the use <strong>of</strong> folate receptortargeted<br />

chemotherapy in canine lymphoma. Folate receptors<br />

(FRs) are proteins which sit on the outer surface <strong>of</strong> some cancer<br />

cells, but are absent on most normal cells in the body. Linking<br />

chemotherapy drugs to folate, which is a B vitamin, targets these<br />

agents specifically to cancer cells, and renders them harmless to<br />

other cells in the body. In collaboration with Endocyte, Inc., a<br />

biotechnology company headquartered in West Lafayette, Ind.,<br />

PCOP identified that approximately 50% <strong>of</strong> canine lymphoma<br />

cases are potential candidates for FR-targeted chemotherapy.<br />

A small group <strong>of</strong> dogs was subsequently treated at the <strong>PVM</strong><br />

<strong>Veterinary</strong> Teaching Hospital, and complete remissions were<br />

achieved in some, with minimal side effects, suggesting that<br />

FR-targeted chemotherapy could be reasonably combined with<br />

CHOP chemotherapy to improve clinical outcome in dogs with<br />

DLBCL. Future studies will involve developing simpler and more<br />

rapid methods to detect FRs in lymphoma cells and employing<br />

more potent FR-targeted agents to treat canine DLBCL.<br />

Dr. Childress further explains that PCOP research on canine<br />

lymphomas also seeks to improve understanding <strong>of</strong> the basic<br />

biology <strong>of</strong> these tumors and the aspects that contribute to