l4c9lj6

l4c9lj6

l4c9lj6

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Spring<br />

2014<br />

Volume 35<br />

Number 1<br />

Missouri Prairie Journal<br />

The Missouri Prairie Foundation<br />

Protecting Native Grasslands<br />

2013 Annual Report Prairie Strips and Row Crops<br />

Prairie Fish Landscaping with Native Small Trees

Message from the President<br />

Jon Wingo at MPF’s<br />

Denison Prairie.<br />

Carol Davit<br />

The earliest settlers to Missouri scorned the<br />

prairie land and built log houses in the<br />

timbered hills. At the time it was believed<br />

that prairie lands would not support crops, but<br />

any doubts about the suitability of unforested<br />

prairie soil for general agriculture were allayed by<br />

General Thomas Adams Smith in the 1820s. As<br />

our Executive Director Carol Davit shared in her<br />

remarks at the 2013 Missouri Prairie Foundation<br />

(MPF) dinner, Smith’s experimental prairie farm in<br />

Saline County was a profitable operation. Smith’s<br />

“Experiment Farm” proved that grasslands were<br />

fertile and could be cultivated with less labor than<br />

woodlands. As quoted in Wentmore’s Gazette of<br />

1837, “Smith was highly respected and news of<br />

his accomplishment spread. His popularization of<br />

prairie farming proved invaluable as the settlement frontier reached the Great<br />

Plains in western Missouri.”<br />

If we move forward a century after the prairie sod was broken, we come<br />

to a lesson learned the hard way. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s resulted from a<br />

devastating drought that increased wind erosion, carrying fertile topsoil from<br />

the Midwest to as far away as Washington, D.C. The Dust Bowl made soil<br />

erosion enter into the American public consciousness of the 1930s.<br />

Today it is evident that, in order to maintain and increase food production,<br />

efforts to prevent soil degradation must become a top priority of our<br />

global society. Soil health is the measure of balance between the physical,<br />

chemical, and biological properties and organismal populations within the<br />

soil. Soil health has become a buzzword among agronomists and some are<br />

looking back to prairie to determine baseline conditions for soil health.<br />

A group from MPF’s Executive Committee met with soil scientists<br />

Dr. David Hammer and Dr. Bob Kremer at the University of Missouri-<br />

Columbia in January to discuss use of MPF’s remnant prairies for research<br />

in setting a baseline for soil health. It was very enlightening and exciting to<br />

learn about cutting-edge technology to evaluate the microbial communities<br />

in the soil such as PFLA marking. Phospholipid fatty acids (PLFA) are<br />

a main component of the membrane (essentially the skin) of all microbes.<br />

PLFA analysis provides direct information on the entire microbial community<br />

in three key areas: viable living biomass, community composition of<br />

population fingerprint, and microbial activity.<br />

I hope you enjoy the articles in this issue of the Missouri Prairie Journal,<br />

including the one on prairie strips. It gives me hope that by embracing<br />

modern-day technologies, proven Best Management Practices, and learning<br />

from the past, our society will be able to continue to conserve soil resources,<br />

natural ecosystems, and produce food supplies sufficient to meet current and<br />

future population demands.<br />

Soil is the foundation of agriculture, but in midcontinental North<br />

America, prairie was the foundation of our agricultural soils.<br />

Jon Wingo, President<br />

The mission of the Missouri Prairie Foundation (MPF)<br />

is to protect and restore prairie and other<br />

native grassland communities through<br />

acquisition, management, education, and research.<br />

Officers<br />

President Jon Wingo, Wentzville, MO<br />

Immediate Past President Stanley M. Parrish, Walnut Grove, MO<br />

Vice President Doris Sherrick, Peculiar, MO<br />

Vice President of Science and Management Bruce Schuette, Troy, MO<br />

Secretary Van Wiskur, Pleasant Hill, MO<br />

Treasurer Laura Church, Kansas City, MO<br />

Directors<br />

Susan E. Appel, Leawood, KS<br />

Dale Blevins, Independence, MO<br />

Glenn Chambers, Columbia, MO<br />

Brian Edmond, Walnut Grove, MO<br />

Margo Farnsworth, Smithville, MO<br />

Page Hereford, St. Louis, MO<br />

Scott Lenharth, Nevada, MO<br />

Wayne Morton, M.D., Osceola, MO<br />

Steve Mowry, Trimble, MO<br />

Donnie Nichols, Warsaw, MO<br />

Jan Sassmann, Bland, MO<br />

Bonnie Teel, Rich Hill, MO<br />

Presidential Appointees<br />

Doug Bauer, St. Louis, MO<br />

Galen Hasler, M.D., Madison, WI<br />

Rick Thom, Jefferson City, MO<br />

Emeritus<br />

Bill Crawford, Columbia, MO<br />

Bill Davit, Washington, MO<br />

Lowell Pugh, Golden City, MO<br />

Owen Sexton, St. Louis, MO<br />

Technical Advisors<br />

Max Alleger, Clinton, MO<br />

Jeff Cantrell, Neosho, MO<br />

Steve Clubine, Windsor, MO<br />

Dennis Figg, Jefferson City, MO<br />

Mike Leahy, Jefferson City, MO<br />

Dr. Quinn Long, St. Louis, MO<br />

Rudi Roeslein, St. Louis, MO<br />

Dr. James Trager, Pacific, MO<br />

Staff<br />

Carol Davit, Executive Director and<br />

Missouri Prairie Journal Editor, Jefferson City, MO<br />

Richard Datema, Prairie Operations Manager, Springfield, MO<br />

2 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 1

Contents<br />

Spring<br />

2014 Volume 35, Number 1<br />

Editor: Carol Davit,<br />

1311 Moreland Ave.<br />

Jefferson City, MO 65101<br />

phone: 573-356-7828<br />

info@moprairie.com<br />

Designer: Tracy Ritter<br />

Technical Review: Mike Leahy,<br />

Bruce Schuette<br />

Proofing: Doris and Bob Sherrick<br />

The Missouri Prairie Journal<br />

is mailed to Missouri Prairie<br />

Foundation members as a benefit<br />

of membership. Please contact the<br />

editor if you have questions about<br />

or ideas for content.<br />

4<br />

2 Message from the President<br />

12<br />

Regular membership dues to<br />

MPF are $35 a year. To become a<br />

member, to renew, or to give a<br />

free gift membership when you<br />

renew, send a check to<br />

membership address:<br />

Missouri Prairie Foundation<br />

c/o Martinsburg Bank<br />

P.O. Box 856<br />

Mexico, MO 65265-0856<br />

or become a member on-line at<br />

www.moprairie.org<br />

16<br />

4 2013 Annual Report<br />

By Carol Davit<br />

12 Prairie Strips<br />

By Lisa Schulte Moore<br />

16 Prairie Streams<br />

By Tom Priesendorf and Kara Tvedt<br />

20 Grow Native!<br />

Landscaping with Native Small Trees<br />

By Alan Branhagen<br />

General e-mail address<br />

info@moprairie.com<br />

Toll-free number<br />

1-888-843-6739<br />

www.moprairie.org<br />

Questions about your membership<br />

or donation? Contact Jane<br />

Schaefer, who administers<br />

MPF’s membership database at<br />

janeschaefer@earthlink.net.<br />

20<br />

23 Steve Clubine’s Native Warm-Season Grass News<br />

27 Jeff Cantrell’s Education on the Prairie<br />

28 Prairie Postings<br />

Back cover Calendar of Events<br />

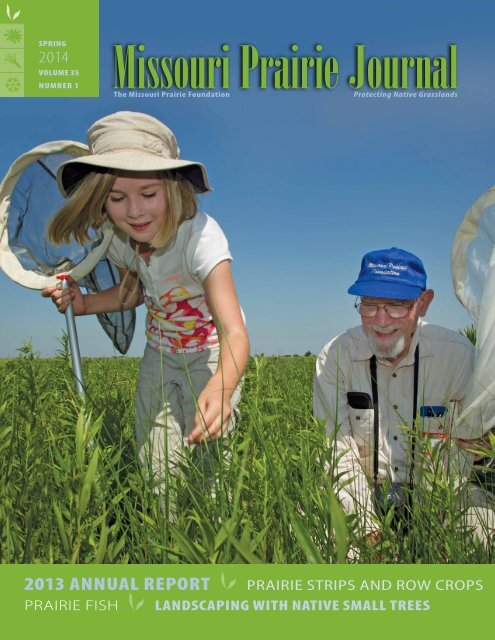

On the cover:<br />

A young butterfly<br />

enthusiast with<br />

lepidopterist Phil Koenig<br />

at MPF’s 2 nd Annual<br />

Prairie BioBlitz at<br />

Golden Prairie in 2011.<br />

Don’t miss MPF’s 5 th<br />

Annual Prairie BioBlitz<br />

June 7 and 8, 2014 at Gay<br />

Feather Prairie in Vernon<br />

County. See back cover<br />

for more information.<br />

Photo by MDC/Noppadol<br />

Paothong<br />

#81779<br />

#8426<br />

Vol. 35 No. 1 Missouri Prairie Journal 3

MPF 2013 annual report<br />

Prairie rose (Rosa carolina)<br />

HOW MPF USED Funding TO CONSERVE PRAIRIE AND<br />

PROVIDE NATIVE PLANT EDUCATION IN 2013<br />

Fundraising and Membership<br />

11.4%<br />

Outreach, Education, Research,<br />

and Grow Native! Program<br />

33.3%<br />

Investment Income<br />

7%<br />

4%<br />

Administration:<br />

8%<br />

Plant, Seed, Hay, and Merchandise Sales<br />

USDA Payments<br />

2.5%<br />

Rent, Annual Dinner<br />

2.5%<br />

Grow Native! Program<br />

1%<br />

Prairie Land Donation<br />

7%<br />

Grants<br />

8%<br />

Phil Koenig<br />

Thank you, Prairie Supporters!<br />

The Missouri Prairie Foundation (MPF) gratefully acknowledges the generosity of all<br />

supporters who enabled us to fulfill our 2013 Campaign for Prairies. Thanks to your<br />

membership contributions and other gifts, we surpassed our $300,000 fundraising goal,<br />

which made it possible for us to not only meet our budget and carry out extensive prairie<br />

conservation, outreach, and research work last year, but also enabled us to purchase a much<br />

needed tractor for fireline establishment and other conservation work! Donors also made<br />

several contributions to our Land Acquisition and Prairie Stewardship Funds.<br />

As more people understand the urgency of conserving Missouri’s rapidly disappearing<br />

original prairie remnants, the MPF community continues to grow. We are delighted that you<br />

are part of it. We look forward to seeing you at our many upcoming events this year.<br />

—Carol Davit, executive director and Missouri Prairie Journal editor<br />

Highlights of 2013 Work<br />

MPF 2013 Sources of Funding<br />

Prairie Management,<br />

Property Taxes, and Insurance<br />

47.3%<br />

Programmatic Expenses<br />

80.6%<br />

Membership dues and other<br />

donations by individuals<br />

68%<br />

MPF’s prairie management and restoration work was made possible thanks to many contributions<br />

from individual supporters (see page 8) and grants from the following organizations, programs, and<br />

corporations: Whole Foods® Market, LUSH cosmetics, Audubon Society of Missouri, Missouri Chapter<br />

of the Wildlife Society, National Wild Turkey Federation, Missouri Department of Conservation costshare<br />

funds, Missouri Bird Conservation Initiative, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Wildlife<br />

Diversity Fund grant program.<br />

In 2013, thanks to your support, a<br />

dedicated, hands-on volunteer board<br />

of directors, and MPF’s two employees,<br />

MPF completed the following:<br />

• Provided quality stewardship of prairies<br />

owned by MPF, Kansas City<br />

Parks and Recreation, The Nature<br />

Conservancy, Ozark Regional Land<br />

Trust, and the Missouri Department of<br />

Conservation, including invasive species<br />

control on more than 1,680 acres<br />

and fireline preparation for prescribed<br />

fires on numerous MPF prairies.<br />

• Completed the structural restoration<br />

of our 2010 acquisition, the 80-acre<br />

Welsch Tract.<br />

• Contracted a dragonfly and damselfly<br />

survey on nine MPF prairies and one<br />

Nature Conservancy prairie, and a<br />

vegetative analysis of MPF’s Golden<br />

Prairie.<br />

• Carried out our first full year of the<br />

Grow Native! program, with workshops<br />

held in Lawrence, KS; Neosho,<br />

MO; submission of monthly articles<br />

for gardening publications; organization<br />

of a successful annual Grow<br />

Native! Professional Member conference,<br />

and many other activities.<br />

• Awarded the second annual MPF<br />

Prairie Gardens Grant to Squier Park<br />

Neighborhood in Kansas City.<br />

4 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 1

• Created new policies to guide MPF’s<br />

implementation of best organizational<br />

and land transaction practices as advocated<br />

by the nationally recognized<br />

Land Trust Alliance.<br />

• Organized 15 events, including MPF’s<br />

Fourth Annual Prairie BioBlitz at<br />

Denison and Lattner Prairies, many<br />

free hikes and tours at native grasslands<br />

around the state, and the MPF annual<br />

dinner that featured Dr. Chip Taylor<br />

of Monarch Watch.<br />

• Produced and sent three issues of the<br />

Missouri Prairie Journal to members,<br />

elected officials, schools, landowners,<br />

and conservation leaders.<br />

• As an active member of the Missouri<br />

Teaming With Wildlife Steering<br />

Committee, advocated for robust FY14<br />

federal State Wildlife Program funding<br />

Carol Davit<br />

Carol Davit<br />

Above from left, MPF board member Jan<br />

Sassmann and Jessica Serrati of Whole Foods<br />

Market® at Whole Foods’ Five Percent Day for<br />

MPF on April 18, 2013.<br />

Top left, prairie enthusiasts enjoy a wagon<br />

tour of Dr. Wayne Morton’s prairie during the<br />

Cole Camp Prairie Day and Evening on the<br />

Prairie held October 12, 2013. The Hi Lonesome<br />

Chapter of the Missouri Master Naturalists<br />

organized the Prairie Day activities and MPF<br />

organized the Evening on the Prairie.<br />

From left is MPF Treasurer Laura Church, MPF<br />

Past President Randy Washburn, and Michael<br />

Laughlin, who served as bartenders during<br />

MPF’s Evening on the Prairie. Washburn generously<br />

donated the wine, refreshments, and<br />

tent rental for the event.<br />

to benefit healthy habitats nationwide.<br />

MPF also supported grassland wildlifefriendly<br />

conservation measures in the<br />

Farm Bill and other state and federal<br />

policies, plans, and strategies.<br />

• Gave presentations on prairie and<br />

native plants to garden clubs and<br />

other groups, and had a presence at<br />

Whole Foods® Markets, the Springfield<br />

Butterfly Festival, America’s<br />

Grasslands National Conference, the<br />

Missouri Bird Conservation Initiative<br />

Conference, and other events.<br />

In January 2013, 47 acres of MPF’s Welsch Tract were seeded with a diverse mix of locally collected<br />

seeds of prairie plants. At left is how the seeded area looked in March 2013, and at right, in August.<br />

The uniformly green area was seeded; the restored canopy structure of the savanna portion of the<br />

Welsch Tract is visible in the background and is a testament to Prairie Operations Manager Richard<br />

Datema’s hard work. The restoration and reconstruction work at the Welsch Tract—immediately<br />

adjacent to MPF’s Coyne Prairie—will expand the prairie habitat in this part of Dade County, MO.<br />

Carol Davit<br />

Photos Susan Parrish<br />

MPF SELECTED FOR $750,000<br />

Award<br />

In 2013, MPF was selected to receive<br />

a $750,000 award from the U.S. Fish<br />

and Wildlife Service and the Missouri<br />

Department of Natural Resources to purchase<br />

and steward prairie in Jasper and<br />

Newton Counties.<br />

In July 2013, MPF submitted a proposal<br />

to apply for funds made available as<br />

a result of a Natural Resources Damage<br />

Assessment (NRDA) settlement with<br />

ASARCO, a lead mining and smelting<br />

company whose operations created environmental<br />

damage while it operated in Jasper<br />

and Newton Counties over the last century.<br />

“The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

and the Missouri Department of Natural<br />

Resources, as trustees of settlement<br />

funds, are pleased to award $750,000<br />

to the Missouri Prairie Foundation for<br />

its proposal to acquire and restore prairie<br />

in southwest Missouri,” said Fish<br />

and Wildlife Biologist Scott Hamilton<br />

with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

Ecological Field Office in Columbia,<br />

MO. NRDA funds are meant to mitigate<br />

for past mining practices that have devastated<br />

significant portions of the landscape<br />

within Jasper and Newton Counties.<br />

“The Missouri Prairie Foundation<br />

was selected for this funding opportunity<br />

because of its track record of successful<br />

prairie management and its impeccable<br />

conservation ethic,” said Hamilton. “We<br />

look forward to a fruitful partnership<br />

with the Missouri Prairie Foundation,<br />

one that results in the increased protection<br />

of tallgrass prairie, a vanishing<br />

resource within Missouri.”<br />

MPF is proud to have been selected<br />

for this award, the funds of which will be<br />

released to MPF as MPF identifies land<br />

to purchase. MPF is actively seeking suitable<br />

parcels of land to aquire from willing<br />

sellers in Jasper and Newton Counties,<br />

where this funding is restricted to purchasing<br />

and stewarding new acquisitions.<br />

MPF welcomes its supporters to contribute<br />

to the maintenance of the prairies it<br />

currently owns and to MPF’s outreach<br />

and education activities.<br />

Vol. 35 No. 1 Missouri Prairie Journal 5

MPF 2013 a n n u a l report<br />

MPF 2013 Member Dinner<br />

More than 130 guests enjoyed<br />

tours, dinner, and a wonderful<br />

presentation by Dr. Chip Taylor<br />

of Monarch Watch at MPF’s 2013<br />

member dinner, organized in conjunction<br />

with Lincoln University’s Native Plant<br />

Program and held at Alberici Corporate<br />

Headquarters in St. Louis.<br />

Guests enjoyed a pre-dinner tour<br />

of Alberici’s native grounds from guides<br />

MPF President Jon Wingo, Dr. Nadia<br />

Navarrete-Tindall of Lincoln University’s<br />

Native Plants Program, MPF Board<br />

Member Doug Bauer, and Grow Native!<br />

Committee Member Simon Barker. At<br />

dinner, guests enjoyed beautiful native<br />

bouquets created by faculty, staff, and<br />

students of Lincoln University.<br />

Many thanks to Alberici for hosting<br />

the event, and to Bethlehem Valley<br />

Vineyards and Schlafly Bottleworks for<br />

providing wine and beer for the event.<br />

Gratitude goes also to MPF member<br />

Ms. Pat Behle, who generously gave each<br />

dinner guest a milkweed plant she had<br />

grown from seed.<br />

Grow Native! Committee Member Simon Barker<br />

leading a group of dinner guests on a tour of<br />

Alberici’s native-planted campus.<br />

Dr. Chip Taylor of Monarch Watch, right,<br />

received a framed print of MPF’s Schwartz<br />

Prairie from MPF President Jon Wingo in appreciation<br />

of his talk at MPF’s 2013 Member Dinner<br />

at Alberici Corporate Headquarters in St. Louis.<br />

6 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 1<br />

Debbie Wingo Debbie Wingo<br />

ATCHISON<br />

HOLT<br />

NODAWAY<br />

ANDREW<br />

BUCHANAN<br />

PLATTE<br />

BARTON<br />

WORTH<br />

GENTRY<br />

DEKALB<br />

CLINTON<br />

CLAY<br />

JACKSON<br />

CASS<br />

BATES<br />

NEWTON<br />

VERNON<br />

JASPER<br />

MCDONALD<br />

HARRISON<br />

DAVIESS<br />

CALDWELL<br />

RAY<br />

HENRY<br />

CEDAR<br />

DADE<br />

LAWRENCE<br />

BARRY<br />

MAP DATA PROVIDED BY CHRIS WIEBERG, MDC.<br />

LAFAYETTE<br />

JOHNSON<br />

ST CLAIR<br />

MERCER<br />

GRUNDY<br />

LIVINGSTON<br />

CARROLL<br />

POLK<br />

STONE<br />

SALINE<br />

PETTIS<br />

BENTON<br />

HICKORY<br />

GREENE<br />

PUTNAM<br />

SULLIVAN<br />

LINN<br />

CHARITON<br />

DALLAS<br />

CHRISTIAN<br />

TANEY<br />

COOPER<br />

MORGAN<br />

CAMDEN<br />

WEBSTER<br />

MACON<br />

HOWARD<br />

SCHUYLER<br />

SCOTLAND<br />

ADAIR<br />

RANDOLPH<br />

MONITEAU<br />

LACLEDE<br />

MILLER<br />

WRIGHT<br />

DOUGLAS<br />

OZARK<br />

BOONE<br />

COLE<br />

PULASKI<br />

MONROE<br />

HOWELL<br />

SHANNON<br />

OREGON<br />

These prairies by MPF and later sold to<br />

the Missouri Department of Conservation<br />

Presettlement Prairie. Of these original 15 million acres, fewer than 90,000 acres remain.<br />

KNOX<br />

SHELBY<br />

MARIES<br />

TEXAS<br />

CLARK<br />

AUDRAIN<br />

CALLAWAY<br />

OSAGE<br />

LEWIS<br />

MARION<br />

RALLS<br />

MONT<br />

GOMERY<br />

GASCONADE<br />

Now in its 48th year, MPF has<br />

acquired more than 3,300<br />

acres of prairie for permanent<br />

protection. With the<br />

conveyance of more than 700<br />

PIKE<br />

of those acres to the Missouri<br />

Department of Conservation,<br />

LINCOLN<br />

MPF currently owns more than<br />

2,600 acres in 16 tracts of<br />

ST CHARLES<br />

WARREN<br />

land, clears trees on properties<br />

ST LOUIS<br />

neighboring MPF land to<br />

FRANKLIN<br />

expand grassland habitat, and<br />

JEFFERSON<br />

provides management services<br />

for thousands of additional<br />

CRAWFORD WASHINGTON<br />

PHELPS<br />

STE GENEVIEVE<br />

acres owned by others.<br />

ST FRANCOIS<br />

PERRY<br />

IRON<br />

DENT<br />

MADISON<br />

CAPE<br />

REYNOLDS<br />

GIRARDEAU<br />

Ecologists rank temperate grasslands—which include Missouri’s tallgrass prairies—as the<br />

least conserved, most threatened major terrestrial habitat type on earth. Prairie protection<br />

efforts in Missouri, therefore, are not only essential to preserving our state’s natural<br />

heritage, but also are significant to national and even global conservation work. MPF is the<br />

only organization in the state whose land conservation efforts are dedicated exclusively to<br />

prairie and other native grasslands.<br />

New MPF Video Produced<br />

MPF now has a beautiful and informative<br />

video to help spread the<br />

message about the importance<br />

of prairie and MPF’s work. The sevenminute<br />

video includes breathtaking<br />

images and insightful expert interviews,<br />

demonstrating the bountiful ecological,<br />

wildlife, and economic benefits native<br />

prairie provides. The video was produced<br />

in fall 2013 and made financially possible<br />

through a generous gift from Rudi<br />

Roeslein/Roeslein Alternative Energy.<br />

The video makes the case that realizing<br />

the environmental benefits of prairie<br />

requires restoring more land with native plants and conserving the remaining 90,000<br />

scattered acres of original native prairie in the state.<br />

“Like so many things in life, we are beginning to realize the benefit of the prairies<br />

now that they’re nearly all gone,” Dr. Peter Raven, President Emeritus of the Missouri<br />

Botanical Garden, said in the video. “They are disappearing very rapidly. And that<br />

really changes the whole natural balance of the whole Northern Hemisphere.”<br />

The video is posted at YouTube, with a link provided at the home page of<br />

www.moprairie.org.<br />

CARTER<br />

RIPLEY<br />

WAYNE<br />

BUTLER<br />

BOLLINGER<br />

DUNKLIN<br />

STODDARD<br />

NEW<br />

MADRID<br />

PEMISCOT<br />

SCOTT<br />

MISSISSIPPI<br />

MPF President Jon Wingo being interviewed by<br />

Mike Martin Media, the company that created<br />

the new MPF video.<br />

Carol Davit

2014 Grow Native!<br />

Resource Guide<br />

To suppliers of native plant products and services<br />

Choose native plants for<br />

• landscaping<br />

• farms and forage<br />

• water management<br />

• wildlife and pollinator habitat<br />

If you would like a free copy of the 2014 Grow<br />

Native! Resource Guide mailed to you, please<br />

call 888-843-6739. Large supplies are also<br />

available to make available at conferences,<br />

garden club meetings, and other events.<br />

Grow Native! Program 2013 Activity<br />

MPF carried out its first full year of the Grow Native! program in 2013.<br />

MPF became the new home of the now 14-year-old native plant education<br />

and marketing program in 2012, when MPF was chosen by the Missouri<br />

Department of Conservation to take on Grow Native!<br />

The work of the Grow Native! program is overseen by a committee of dedicated<br />

native plant advocates and native landscaping industry professionals. Highlights of<br />

Grow Native! program activity in 2013 include:<br />

• organizing three successful native landscaping workshops held in Lawrence, KS,<br />

and Neosho, MO and also the Native Plant Education Tract at the 2013 National<br />

Green Centre in St. Louis.<br />

• providing native plant outreach at numerous events, including the Missouri<br />

Landscape and Nursery Association’s (MLNA’s) Nuts and Bolts Continuing<br />

Education Conference, MLNA’s Field Day, the Missouri Green Industry<br />

Conference, and the Statewide Master Gardeners’ Conference.<br />

• giving native plant talks to the Fulton Garden Club, Lake of the Ozarks Watershed<br />

Alliance, and Moberly Area Community College Plant Biology students.<br />

• submitting native landscaping articles monthly to Missouri Ruralist and Kansas City<br />

Gardener magazines, and publishing three native landscaping articles in the Missouri<br />

Prairie Journal.<br />

• creating the 2014 Grow Native! Resource Guide to suppliers of native plant<br />

products and services, featuring 2014 Grow Native! Professional Members.<br />

• organizing a successful Grow Native! Professional Member Conference with<br />

informative speakers, hosted by the University of MO–Columbia.<br />

• creating a model Native Landscaping Ordinance, available at www.grownative.org.<br />

In 2013, MPF was bequeathed a 34-acre<br />

original prairie in Hickory County from the Ann<br />

Louise Stark Trust. Stark Family Prairie is home<br />

to prairie hyacinth (Camassia angusta), above,<br />

and many other native prairie species.<br />

Bruce Schuette<br />

2013 Native Landscape ChallengeFor eight years, the St. Louis<br />

Chapter of Wild Ones has<br />

invited homeowners in the<br />

St. Louis area to participate in<br />

a native landscape challenge. In<br />

2013, thirteen landowners competed<br />

for this front yard native makeover<br />

orchestrated by Wild Ones,<br />

Shaw Nature Reserve, and MPF’s<br />

Grow Native! program.<br />

In May 2013, Challenge<br />

volunteer organizers reviewed the submissions and chose that of homeowner Dawn<br />

Weber, of the City of St. Louis, because her yard offered a “blank slate” and potential<br />

for a rain garden. Over the past summer, landscape designer, Wild Ones member,<br />

and Grow Native! professional member Jeanne Cablish instructed Weber in preparing<br />

her front yard for the native plantings, installed by Scott Woodbury of Shaw Nature<br />

Reserve and a crew of Wild Ones volunteers on a Saturday in September 2013.<br />

The Grow Native! program provided $500 for the purchase of native plants.<br />

Congratulation to Ms. Weber and all involved in this successful project.<br />

sherri DeRousse<br />

—Ed Schmidt, MPF member and president of the St. Louis Chapter of Wild Ones<br />

Vol. 35 No. 1 Missouri Prairie Journal 7

Thank you<br />

MPF 2013 a n n u a l report<br />

2013 Grow Native!<br />

Ambassador Award<br />

The Grow Native! program annually recognizes<br />

an individual who has made outstanding<br />

contributions to the advancement of the use<br />

and promotion of native plants and native plant<br />

landscaping. Recognition is awarded in the form<br />

of the Grow Native! Ambassador Award.<br />

At the 2013 Grow Native! professional<br />

member meeting in November, Grow Native!<br />

Committee Chair Carrie Coyne, above left,<br />

announced that Mr. Bill Ruppert of Kirkwood,<br />

MO, had been selected as the 2013 Grow Native!<br />

Ambassador Awardee.<br />

Ruppert has been an advocate for native plants<br />

for many years—from his work at the Woodland<br />

and Floral Gardens at the University of Missouri–<br />

Columbia in the 1980s to his current work as a<br />

member of the Grow Native! Committee.<br />

Over the course of 2013, Ruppert went outside<br />

of the “native plant establishment” to forge<br />

new alliances for natives and help new audiences<br />

see the immense value of native plants.<br />

In March 2013, Ruppert taught the importance<br />

of natives to members of the Missouri<br />

Landscape and Nursery Association at their annual<br />

“Nuts and Bolts” conference. He also worked<br />

hard to introduce the importance of natives to<br />

members of the turf industry, to demonstrate<br />

how native plantings can complement traditional<br />

turf. This work has led to a pilot project at the<br />

University of Missouri’s South Farm. In addition,<br />

Ruppert has gone all the way to the U.S. Senate<br />

in his quest to bring native trees to the Gateway<br />

Arch grounds. Congratulations, Bill Ruppert!<br />

8 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 1<br />

Robert Weaver<br />

$30,000 AND ABOVE<br />

Estate of Ms. Linden Trial*<br />

$20,000 TO $29,999<br />

Andrew Love, Edward K. Love<br />

Conservation Foundation*<br />

$10,000 TO $19,999<br />

Ronald and Suzanne Berry*<br />

Rudi Roeslein*<br />

$5,000 TO $9,999<br />

Anonymous<br />

Margaret Holyfield and<br />

Maurice Meslans*<br />

Pat Jones*<br />

$2,500 TO $4,999<br />

James and Charlene Jackson*<br />

Robert and Cathleen Hansen*<br />

Doris and Bob Sherrick *<br />

Robert J. Trulaske, Jr. Family<br />

Foundation<br />

$1,000 to $2,499<br />

Susan Appel<br />

Scott Avetta<br />

Robert and Martha Barnhardt*<br />

Rodger and Rita Benson<br />

Dale and Marla Blevins*<br />

Mildred Blevins<br />

Bill Crawford*<br />

Mrs. Henry (Nancy) Day*<br />

Susan Canull and Des Pain<br />

Leo and Kay Drey*<br />

Margo Farnsworth and<br />

Jim Pascoe<br />

Judith Felder*<br />

Betsy Garrett<br />

James and Joan Garrison*<br />

Francine Glass<br />

Norma Hamm<br />

Page and Fonda Hereford*<br />

John and Lucia Hulston,<br />

Hulston Family Foundation*<br />

Chris and Tricia Jerome<br />

Harold John*<br />

Warren and Susan Lammert*<br />

Susan Marker<br />

Michael McMullen*<br />

Gina Miller*<br />

Donnie and Kim Nichols<br />

Frank and Judy Oberle*<br />

Sharon Pedersen<br />

F. Leland Russell and<br />

Mary Jameson*<br />

Edgar Schmidt*<br />

Bonnie Teel<br />

W. Randall Washburn*<br />

David and Judy Young<br />

$500 to $999<br />

Robert and Linda Ballard<br />

Alice Counts, Ozarks AAZK<br />

Karen and Paul Cox<br />

Rebecca Erickson<br />

Elizabeth and Scott Galante<br />

James and Marilyn Hebenstreit<br />

Cynthia Hobart<br />

Jerome and Billie Jerome<br />

John and Deborah Killmer<br />

Steve Maritz<br />

James and Nancy Martin<br />

John and Connie McPheeters<br />

David Mesker and<br />

Dorothy Haase<br />

Wayne Morton<br />

J. Sarah Myers and Dennis<br />

O’Brien<br />

Barbara and William Pickard<br />

Dale Shriver and Judith Rogers<br />

Mary and Mike Skinner<br />

James and Jan Trager<br />

Sue Ann and Richard Wright<br />

$250 TO $499<br />

John Besser and Cathy Richter<br />

Mark Brodkey<br />

John Camp<br />

Steve and Debbie Clark<br />

Stephen Davis<br />

Robert Elworth<br />

Bob and Sara Caulk, Fayetteville<br />

Arkansas Natural Heritage<br />

Association<br />

Cheryl and Chuck Fletcher<br />

Ellen Sue Goodman, Bluejay<br />

Farm<br />

Ruth Grant and Howard<br />

Schwartz<br />

Dennis Gredell and<br />

Lori Wohlschlaeger<br />

Bucky Green<br />

Ann Grotjan, Full Spectrum<br />

Photo and Audio<br />

Rusty and Prae Hathcock<br />

Bonnie Heidy<br />

Joe Holland<br />

Jim Hull<br />

Joseph and Anne Jezak<br />

Robert and Barbara Kipfer<br />

Ward and Carol Klein<br />

Janet Koester<br />

Linda S. Labrayere Revocable<br />

Trust<br />

Laurence and Dorothy Lambert<br />

Theresa and Joseph Long<br />

Julia Marsden<br />

MHR, Inc.<br />

John and Anita O’Connell<br />

Orbie Overly<br />

Paul Petty<br />

Pizzo Native Plant Nursery<br />

Stan and Audrey Putthoff<br />

Roger and Anita Randolph<br />

Gordon and Barbara Risk<br />

Molly Rundquist<br />

Caroline and William Sant<br />

Walter and Marie Schmitz<br />

James Sullivan<br />

Charles and Nancy Van Dyke<br />

Julie Wiegand<br />

Jack’s Girls, Kay Wood<br />

$100 TO $249<br />

Hearld and Marge Ambler<br />

Toni Armstrong and<br />

Richard Spener<br />

Alan and Mary Atterbury<br />

George and Angel Avery<br />

Daniel and Joann Barklage<br />

Joe Bassler<br />

Bauer Equity Partners<br />

David and Nancy Bedan<br />

Edward Beheler,<br />

Broken Arrow Ranch<br />

Richard Beheler,<br />

Broken Arrow Ranch<br />

Pat Behle<br />

Patricia Bellington<br />

Nick and Denise Bertram<br />

Dan and Jenny Blesi<br />

Peter Bloch and Marsha Richins<br />

Allan and Nancy Bornstein<br />

William and Monica Bowman<br />

Bettye and Robert Boyd<br />

John and Regina Brennan<br />

Steve Buback<br />

William and Ester Bultas<br />

Mary Bumgarner<br />

Robert Campbell<br />

Jeffrey Cantrell<br />

Ann Case<br />

Juliet Cassady<br />

David and Ann Catlin<br />

Robert Charity<br />

Agnes Chouteau<br />

Alice Christensen<br />

Laura Christisen<br />

Louis Clairmont and<br />

Deborah Barker<br />

Jean C. Coday<br />

Raymond Coffey<br />

Virginia Burns Cromer<br />

Richard Cronemeyer<br />

Jo Anna Dale<br />

William Danforth<br />

Dolly Darigo<br />

Sue Davis<br />

Bill and Joyce Davit<br />

Richard and Eleanor Dawson<br />

Ann Day and Roger Clawitter<br />

Kevin and Janet Day<br />

Ronald and Sue Dellbringge<br />

Paula Diaz<br />

Mike Doyen<br />

Harold Draper<br />

DST Systems, Inc. Matching<br />

Gifts Program<br />

Ethan Duke and Dana Ripper,<br />

Missouri River Bird<br />

Observatory<br />

Susan Dyer<br />

Majorie Eddy<br />

Jack Edmiston<br />

Earl and Darryl Edwards<br />

David and Judy Elsberry<br />

Danny Engelage<br />

J. Robert Farkas<br />

Federated Garden Clubs<br />

of Missouri, Inc.<br />

James and Cynthia Felts<br />

E. B. and Dorothy Feutz<br />

Dennis Figg<br />

Susan Flader<br />

Bill and Martha Folk<br />

Gretta Forrester and<br />

Walker Gaffney<br />

Joynce Fuhr, Integrated<br />

Manufacturing Technologies<br />

Dale and Patricia Funk<br />

Savannah and William B.<br />

Furman<br />

Robin and Joanne Gannon<br />

Robert Garrecht<br />

Gary and Lillian Giessow<br />

Margaret Gilleo<br />

Len and Tammy Gilmore<br />

Nelson and Suan Greenlund<br />

David Gronefeld<br />

Lloyd and Ruth Gross<br />

Robert Hagg and Reta Roe<br />

Jeffrey Halbgewachs and<br />

Kathleen Meier<br />

Thomas Hall<br />

Natalie Halpin<br />

Charles Hapke<br />

Ted Harris<br />

Andrew Hartigan<br />

Hartke Nursery<br />

Galen Hasler<br />

Oscar Hawksley<br />

Ivan Hayworth<br />

Charlotte Herman<br />

Michael and Jeanne Hevesy<br />

Rex and Martha Hill<br />

Mary Ann and Ronald Hill USN<br />

(Ret)

,<br />

MPF Members and Other Supporters<br />

Who Made Contributions in 2013<br />

Alan and Sharon Hillard<br />

Bob Hotfelder<br />

Larry and Joan Hummel<br />

Carol Hunt<br />

Carole and Bob Hunter<br />

Robert and Michele Hurst<br />

Tom and Anne Hutton<br />

Teresa Ittner<br />

Elizabeth Jackson<br />

Pauline Jaworski<br />

Robert and Joan Jefferson<br />

Tom Jegla<br />

Lance and Pat Jessee<br />

Paul and Barbra Johnson<br />

Leslie and Chad Jordon<br />

George Kambouris<br />

Mike and Betsy Keleher<br />

Jay Kelly<br />

Robin Kern<br />

David Kirk<br />

Janet Kister and David Wolfe<br />

Roger and Lynda Koenke<br />

Keith Kretzmer<br />

Jim and Mary Kriegshauser<br />

Russ and Kim Krohn<br />

Douglas and Deborah Ladd<br />

Lea Langdon<br />

John and Nancy Lewis<br />

Michelle Liberton<br />

Maurice and Ernesta<br />

Lonsway<br />

Genesis Nursery, Dennis and<br />

Kathy Lubbs<br />

Barbara Lucks<br />

Patricia Luedders<br />

Roger Maddux and Cynthia<br />

Hildebrand<br />

Tom and Evelyn Mangan<br />

Dennis and Tina Markwardt<br />

Doug and Beth Martin<br />

Ford Maurer<br />

Marty and Sara McCambridge<br />

Rosa and Bob McHenry III<br />

Fred McQueary<br />

Thomas McRoberts<br />

Pat and Peter McDonald<br />

Chip and Teresa McGeehan<br />

Larry and Belinda Mechlin<br />

Stan Mehrhoff<br />

Terry and Ellen Meier<br />

Stephen Merlo<br />

Walter and Cynthia Metcalfe<br />

Kristine Metter<br />

Philip and Pearl Miller<br />

Richard and Carol Mock<br />

Monsanto Matching Gifts<br />

Program<br />

William and Mary Moran<br />

Lydia Mower<br />

Dean and Bette Murphy<br />

Elaine and Charles Nash<br />

Paul and Suzanne Nauert<br />

Thompson Nelson and<br />

Lorraine Gordon<br />

George and Barbara Nichols<br />

Thomas Nichols<br />

Doris Niehoff<br />

Thomas and Lynn Noyes<br />

Marsha Nyberg and<br />

Gary Leabman<br />

Larry O’Reilly<br />

James and Mary Pandjiris<br />

Noppadol Paothong<br />

Stanley and Susan Parrish<br />

Burton Paul, Tuque Prairie<br />

Farms, Inc.<br />

Vincent and Jane Perna<br />

Lauri Peterson<br />

Glenn and Ilayna Pickett<br />

Dick and Donna Pouch<br />

Joel Pratt<br />

Caroline Pufalt<br />

Stacy Pugh-Towe and<br />

Monty Towe<br />

Simon and Vicki Pursifull<br />

Sue Reed<br />

Nancy and Dwyer Reynolds<br />

Garden Club of Richmond<br />

Heights<br />

Cheryl Ricke<br />

Tracy Ritter<br />

Derron and Connie Rolf<br />

Paul Ross, Jr.<br />

Sebastian Rueckert<br />

Michael Rues and<br />

Ann Wakeman<br />

Winnie Runge-Stribling and<br />

Charles Stribling<br />

Robert Sabin<br />

Becky Sanborn<br />

Jane Schaefer<br />

Mike and Rose Schulte<br />

Arlene Segal<br />

Robert Semb<br />

James and Paula Shannon<br />

Jean and Jim Shoemaker<br />

Charles and Charlotte Skornia<br />

Eleanor Smith and James<br />

Droesch<br />

Alistar and Karen Stahlhut<br />

Marvin and Karen Staloch<br />

Leisa and Tony Stevens<br />

Rheba Symeonoglou<br />

Justin and Dana Thomas,<br />

Institute of Botanical Training<br />

Lisa Thomas<br />

Herbert and Susan Tillema<br />

Michael Todt<br />

Nancy Tongren<br />

Andy Tribble<br />

David and Jennifer Urich<br />

Henk and Nita Van Der Werff<br />

Joel and Marty Vance<br />

Thomas Vaughn<br />

Henry and Susan Warshaw<br />

Samuel Watts<br />

Stephen Weissman<br />

Thomas Wendel and Deborah<br />

Butterfli<br />

Mark WIllard<br />

James and Alice Williamson<br />

Carole Woodson<br />

Dalton Wright<br />

Rip Yasinski and Trish Quintenez<br />

Glynn Young<br />

Martha and Douglas Younkin<br />

$50 TO $99<br />

Joe and Dianna Adorjan, The<br />

Adorjan Family Foundation<br />

Janice Albers<br />

Thomas Alexander and<br />

Laura Rogers<br />

David and Sandra Alspaugh<br />

Bill Ambrose<br />

Kathleen and Harold Anderson<br />

Robert Arrowsmith<br />

David Austin<br />

John and Agnes Baldetti<br />

Phyllis Banks<br />

Kent Bankus<br />

Ralph Barker and Margaret<br />

Vandeven<br />

Pamela and Jerry Barnabee<br />

Lesa Beamer<br />

Anastasia Becker<br />

Drew Beeman<br />

Sarah Beier<br />

Margaret Bergfeld<br />

Robert Bidstrup<br />

Joann Billington<br />

William and Dianne<br />

Blankenship<br />

Alice Block and Frank Flinn<br />

Nicole Blumner and Warren<br />

Rosenblum<br />

Leona Bohm<br />

Jo Ann Bonadonna<br />

Ron Boudouris<br />

Linda and Dale Bourg<br />

Dennis Bozzay<br />

William and Joan Brock<br />

Sandra Brumfield<br />

Fred and Susan Burk<br />

Charles Burwick<br />

James and Anne Campbell<br />

Donald and Delores Cannon<br />

Harvey and Francine Cantor<br />

Tom Carr<br />

Linda and Jack Childers<br />

James and Cindy Clark<br />

Theresa Cline<br />

Gregory and Cynthia Colvin<br />

Betsy Betros<br />

J. Richard Cone Living Trust<br />

Katherine Connor<br />

John T. Cool<br />

Fred and Nancy Coombs<br />

Covidien<br />

Paul and Martha Cross<br />

John and Kathryn Crouch<br />

Michael Cullinan<br />

Jill Cumming<br />

Rupert Cutler<br />

Wray and Doris Darr<br />

Mickey and Steven Delfelder<br />

Mary and Wallace Diboll<br />

Donald Dick<br />

Daron Dierkes<br />

Lorna and Henry Domke<br />

Denny and Martha Donnell<br />

Carolyn Doyle<br />

Harold Eagan<br />

Brian Edmond and Michelle<br />

Bowe<br />

Catherine Ebbesmeyer<br />

Brent Edwards<br />

Marguerite and James Ellis<br />

William L. Fair<br />

William and Susan Fales<br />

Jean and Kevin Feltz<br />

William Fessler<br />

Rebekah and Don Foote<br />

Larry and Pam Foresman<br />

Betty and Jim Forrester<br />

Inge Maria Foster<br />

Ivor and Susan Fredrickson<br />

Wayne Fry<br />

Elizabeth George<br />

John George<br />

Karen Goellner<br />

Leah Gay Goessling<br />

Gerald and Anita Gorman<br />

Rick Gray<br />

Jim Greenstreet, AllRisk<br />

Resources, LLC.<br />

John and Mary Grice<br />

Darin Groll<br />

Chris Gumper<br />

Randy Haas<br />

Michael and Kathryn Haggans<br />

Jerry and Linda Haley<br />

Kenneth and Cleo Hamilton<br />

Harold and Kristy Harden<br />

Marie Hasan<br />

Charles and Janie Hayden<br />

Sylvia and Daniel Hein<br />

Josephine Hereford<br />

Roger and Nancy Hershey<br />

Vera Herter<br />

David and Tina Hinds<br />

Sue and Steve Holcomb<br />

Mike Holley<br />

Penny (Pauline) Holtzmann<br />

Kathleen and Lawrence Horgan<br />

Emily and Paul Horner<br />

Robert and Linda Hrabik<br />

Paul Hubert<br />

Jan Hugh<br />

Suzanne Hunt and Andrew<br />

Gredell<br />

Kevin Hurley<br />

Gary Jackson<br />

Edwin Jacobs<br />

Bernie and Sally Jezak<br />

Betty Johnson<br />

G. D. and Penny Johnson<br />

Suzanne and Jim Johnson<br />

Vicki Johnson<br />

Suzanne Hamby Jones<br />

Jill Jordan<br />

Laura Kahl<br />

Margaret and Henry Kaltenthaler<br />

Arvil Kappelmann<br />

Doug Kappelmann<br />

Mark Katich<br />

Buck and Patricia Keagy<br />

Robert and Marcia Kern<br />

Kim Killian<br />

Anna Kizer<br />

Amy and Nathan Klaas<br />

Gary Klearman<br />

Laurie Kleen<br />

Don and Ruth Kollmeyer<br />

Scott and Cindy Kranz<br />

Kent Kuhlman<br />

Curtis and Deborah Kukal<br />

Alberto and Judith Lambayan<br />

Leona Lambert-Suchet<br />

Jerrold and Harriet Lander<br />

Wayne and Marilyn Langston<br />

Dean and Dianna Laswell<br />

Jim and Suzanne Lehr<br />

Ann and Dan Liles<br />

Leslie Limberg<br />

Curtis Long<br />

Quinn and Melissa Long<br />

Glenn and Judith Longworth<br />

Gretchen and Lynn Loudermilk<br />

Ronald W. and Margie Lumpe<br />

Steve and Diane Lumpkin<br />

James and Anita Lyon<br />

William Mabee<br />

Elsie and James Mace<br />

Michelle Macke<br />

Tim and Trana Madsen<br />

Will and Laura Marshall<br />

Marcel Maupin<br />

Gayla and Steve May<br />

Ric and Jean Mayer<br />

Tom and Phebe McCutcheon<br />

Tom McGraw and Elizabeth<br />

Prindable<br />

Bill McGuire<br />

K.D. Meares and Terri Smith<br />

Holly Mehl<br />

Vaughn Meister and Ralph<br />

Hanline<br />

Dale and Beverly Mermoud<br />

Kathleen Metter<br />

William and Nancy Moss<br />

Michael and Janet Mulholland<br />

Elizabeth Myers<br />

Lisa and Robert Nansteel<br />

Mary Nemecek<br />

June Newman<br />

Burton Noll<br />

Harry O’Toole<br />

Norman Parker<br />

Nancy and Michael Pawol<br />

Richard Pedroley<br />

Bob and Pat Perry<br />

Nathaniel and Juanita Peters<br />

Ross and Crystal Peterson<br />

M. June Pfefer<br />

Lee and Dennis Phillion<br />

Mark Phipps<br />

Joel Picus<br />

Jeanie Scott Pillen<br />

Ray Poninski<br />

Stephen and Beverly Price<br />

Susan Pyle<br />

Edward Quinn<br />

Anne and Horton Robert<br />

Rankin<br />

Dennis Reed and Kathie Bishop<br />

Wayne and Mary Reinert<br />

Lynda Richards<br />

Thomas Richter<br />

Mark Robbins, University of<br />

Kansas Biodiversity Institute<br />

Bill Roberts<br />

Vol. 35 No. 1 Missouri Prairie Journal 9

Thank you, MPF Members and Other Supporters Who Made Contributions in 2013 continued<br />

MPF 2013 a n n u a l report<br />

Bill and Emily Robertson<br />

Michael Robertson<br />

Richard and Marie Robertson<br />

Wendell Roehrs<br />

John Roeslein<br />

Jason and Amy Rogers<br />

Marc and Becky Romine<br />

Michael Roper<br />

George Rose<br />

William Rowe<br />

Russell and Ann Runge<br />

Mark Ryan and Carol<br />

Mertensmeyer<br />

Thomas Saladin<br />

Stephen Savage<br />

Gary Schimmelpfenig and<br />

Christine Torlina<br />

Jackie Schirn<br />

David and Alice Schlessinger<br />

Lorraine Schraut<br />

Don and Deb Schultehenrich<br />

Thom and Jane Sehnert<br />

David Setzer and Linda<br />

Headrick<br />

Jerry Shatto<br />

Charles and Mary Sheppard<br />

Steven and Christine Sheriff<br />

Kirk Sibley and Koryen Collins<br />

Alan and June Siegerist<br />

Richard Sinise<br />

Sisters of the Most Precious<br />

Blood<br />

Ted and Beth Slegesky<br />

Christine Smith and George<br />

Fuson<br />

Suzi Spoon<br />

Deanna Staehling<br />

George Stalker and Jean<br />

Keskulla<br />

John and Judith Stann<br />

Richard Steel<br />

Warren Stemme<br />

The Straub Family<br />

Robert Strickler<br />

Bill Summers<br />

Christine and Rocky Swiger<br />

Judith Tharp<br />

Richard and Karen Thom<br />

Steve Thomas<br />

Mark and Maria Thornhill<br />

Lydia Toth<br />

Mike and Kathy Trier<br />

Dennis and Adele Tuchler<br />

Matthew Van Dyke<br />

Jim Van Eman<br />

Don and Paula Vaughn<br />

Wayne Wainwright<br />

Paul and Robin Wallace<br />

David Waltemath<br />

Richard Watson<br />

Jan Weaver<br />

10 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 1<br />

John Wayne and Mary Weaver<br />

Mary and Steve Weinstein<br />

Rad Widmer<br />

Linda Williams<br />

James and Barbara Willock<br />

Loel and Iana Wilson<br />

James Winn<br />

Duane and Judith Woltjen<br />

Teresa Woody and Rik Siro<br />

Waiva Worthley<br />

Becky Wylie<br />

Julie Youmans and Fred Young<br />

$35 TO $49<br />

Monte Abbott<br />

Charlotte Adelman and<br />

Bernard Schwartz<br />

Bill and Lynn Admire<br />

Tom and Cathy Aley<br />

Kathy Allen<br />

Russell Allen<br />

Rose Allison<br />

Denise Anderson<br />

Michelle Anderson<br />

Carl Armontrout<br />

Grace the Earth Foundation<br />

Roy Bailey<br />

Byron Baker, Baker Brothers<br />

Farm<br />

Debra Jo and Barry Baker<br />

Robert and Ruby Ball<br />

Carol Ballard<br />

Timothy Banek<br />

Steven Barco<br />

Matt Barnes<br />

M. Neil and Debra Bass<br />

John and Emmi Bay<br />

Jack Beckett<br />

John and Carole Behrer<br />

Trace J. Bell<br />

Kim Bellemere<br />

Terry and Carol Berkland<br />

Linda Bishop<br />

David Bloomberg<br />

Don Bohler<br />

Dennis and Kathleen Bopp<br />

John S. and Laura Bosnak<br />

Beverly Boucher<br />

Bob and Becky Bowling<br />

David Bradley and C. McGennis<br />

Kathy Brady<br />

Charles Bramlage<br />

Jim Braswell, Show-Me-Nature<br />

Photography<br />

Dennis Brewer<br />

Mike and Martha Brooks<br />

Curtis Brown<br />

Glenn Brown<br />

William and Sibylla Brown<br />

Jennifer and William Browning<br />

John Brueggemann<br />

MDC<br />

Jo and Kelly Bryant<br />

Joseph Bubulka<br />

Amy and Mike Buechler<br />

Tom and Ellen Burkemper<br />

Linda Burns and Chuck Mason<br />

Bob Burton<br />

Steve Burton<br />

Penney Bush-Boyce<br />

Ivy and Don Canole<br />

Dale and Connie Carpentier<br />

Jerry and Linda Castillon<br />

Charlie and Zoe Caywood<br />

Glenn Chambers<br />

Phyllis Chancellor<br />

Hilary David Chapman<br />

Michael Cheek<br />

Jim and Brenda Christ<br />

Joe and Ginny Church<br />

Bill Clark<br />

Candace Clark<br />

Elaine Clark<br />

Marty Clark<br />

Mike and Heidi Clark<br />

Patricia Clarke<br />

Robert Clearwater<br />

Steve Clubine<br />

Diane Cobb, Alpha Chiropractic<br />

Center, Inc.<br />

Cyndi and James Cogbill<br />

Ron Colatskie<br />

Betsy Collins<br />

Stevie Collins<br />

James Conner<br />

James Connolly<br />

Brenda Cook<br />

Kate Corwin<br />

Tami Courtney<br />

Steve Craig and Amy Short<br />

Gerry Crawford<br />

Lisa Culley<br />

David Darnold<br />

Joyce Davenport<br />

Carol Davit and Michael Leahy<br />

Karen Day<br />

Richard and Susan Day<br />

Laurel DeFreece<br />

Phil and Martha Delestrez<br />

John Dengler and Carol<br />

Shoptaugh<br />

Valerie and Ron Dent<br />

J. Brock Diener<br />

Damien Dixon<br />

Dan Drees and Susan<br />

Farrington<br />

Kevin Drewyer<br />

William Dreyer<br />

Bradley and Patricia Dyke<br />

Jack and Evelyn Eads<br />

William Eddleman<br />

Neil and Irene Ellis<br />

Edwin Elzemeyer, Red Fox Farm<br />

Theresa Enderle<br />

David Eppelsheimer, Sr.<br />

David Erickson<br />

Spencer Ernst<br />

Stephen Fay<br />

Louesa Runge Fine<br />

Jerry and Mary Ann Fischer<br />

Suzanne Fischer<br />

Michael Flaherty<br />

Michael Fleming and Jody<br />

Pense, Sam Baker<br />

Concessions, Inc.<br />

Louise and George Flenner<br />

Mary Foley<br />

Scott Foley<br />

Beverly Foote<br />

Roy Fortner<br />

Kathleen Frank<br />

Robin and Debra Frank<br />

Elizabeth Franklin<br />

Linda Frederick<br />

Gary and Patti Freeman<br />

Paul and Heather Frese<br />

Thomas Ganfield<br />

Norman and Vicki Garton<br />

Jim Gebhart<br />

Virgil Gehlbach<br />

Stan and Suzanne Gentry<br />

Ona Gieschen<br />

Beverly Gieselman<br />

Bryan Goeke<br />

Deborah Good<br />

Larry Goodwin<br />

Lee Ann Googe<br />

Diana Gray<br />

Kelly Green<br />

Rebecca Green and Suren<br />

Fernando<br />

Kenyon Greene<br />

Ben Grossman, St. Charles<br />

County Parks & Recreation<br />

James and Janine Guelker<br />

Walter and Ruth Gusdorf<br />

Andy Guti and Sherri<br />

DeRousee, Bear Creek Prairie<br />

Properties, LLC.<br />

Hilary Haley<br />

Walter Hammond<br />

Melanie Haney<br />

Keith Hannaman<br />

Jeff Hansen<br />

Carol Harkrider<br />

Marilyn Harlan<br />

Ray Harmon<br />

Leann Harrell<br />

Trevor Harris<br />

Jo Ellen Hart<br />

Roger Helling<br />

Sue Helm<br />

Rollie Henkes<br />

Ann Henning<br />

Nick and Erin Hereford,<br />

Hereford Concrete Products,<br />

Inc.<br />

Jeanne Heuser<br />

Steve Heying<br />

Harriet Hezel<br />

Steve Hilty<br />

Daniel Hof, Hofco Farms<br />

Carla and Kevin Hogan<br />

Dennis Hogan<br />

Holt Farms, Inc.<br />

Jenny Hopwood-Dickson and<br />

Tim Dickson<br />

Karen Horny<br />

Gary House<br />

Linda Houston<br />

Lessie Hudson<br />

William Hughes<br />

June Hutson<br />

Janet Iggulden<br />

Dan Isom<br />

David and Eva Jankowski<br />

Brian Johnson<br />

Delwin Johnson<br />

Kay and Betty Johnson<br />

Angie and Aaron Jungbluth<br />

Kansas City Public Library<br />

John Karel<br />

Irene Karns<br />

Fred Kautt<br />

Peggy Keilholz<br />

Dan Kelly<br />

Sue and Dan Kelly<br />

Kelly Kindscher and Maggie<br />

Riggs<br />

Albert Kitta<br />

Wallace and Norma Klein<br />

Jean Knoll<br />

Steve Kodner<br />

Thomas Martin and Amanda<br />

Cuca Koehler<br />

Phillip Koenig<br />

Charles and Grace Koerner<br />

Daniel Kopf<br />

Robert and Maureen Kremer<br />

Robin and Mike Kruse<br />

Paul and Jane Kruty<br />

Joseph and Linda Kurz<br />

Larry and Marvin Lackamp<br />

William and Virginia Landers<br />

Jim and Mariann Leahy<br />

George Leaming<br />

Bob Lee<br />

J. E. Leonard<br />

Sherry Leonardo<br />

Beth Lewandowski<br />

Catherine Lewer<br />

Howard and Verna Lewis<br />

Lawrence and Ruth Lewis<br />

Curtis Lichty<br />

Mark and Pamela Lindenmeyer<br />

Steven Linford<br />

Mark Loehnig<br />

John Logan<br />

Bob Lorance<br />

Douglas Maag<br />

Tim Maddern<br />

Larry and Shirley Maher<br />

Edward Manring<br />

Jude and Mary Markway<br />

Peter and Carolyn Maurice<br />

Loretta McClure<br />

Ronald McCracken, RGM<br />

Investments, LLC.<br />

Wallace McDonald<br />

Robert McPheeters<br />

M. H. and W. R. McVicker<br />

Mary McCarthy<br />

Alberta McGilligan<br />

McRoberts Farm, Inc.<br />

Lenora Medcalf<br />

Larry Melton<br />

Melodie and Mark Metje<br />

Beth Meyers<br />

Florence Middleton<br />

Jan Miller<br />

Stuart Miller<br />

P. E. Minton<br />

Campbell Mock<br />

Steve and Judy Mohler<br />

Ricky and Lou Mongler<br />

Cecil and Geraldine Moore<br />

Leroy and Diane Morarity<br />

Patricia and John Mort<br />

Mark Mudd<br />

Joanne Mueller<br />

Billie Mullins<br />

David and Gunilla Murphy<br />

Angela Nance<br />

Jan and Bill Neale<br />

Robert Nellums<br />

Eric and Barbara Nelson<br />

Michelle Newby and James<br />

Veraguth<br />

Greg Newell<br />

Krista Noel<br />

Brett and Carrie O’Brien<br />

Philip O’Hare<br />

Maria O’Keefe<br />

Bill Olson<br />

Chester R. Owen<br />

Ozark Wilderness Waterways<br />

Club<br />

Janette and Russell Pace<br />

Bruce Palmer

Nancy and Kent Parrish<br />

Scott Patrick<br />

Cynthia Pavelka<br />

Cindy Pence<br />

Carla Peniston<br />

Wayne Perkins<br />

Brock Pfost, White Cloud<br />

Engineering<br />

Paul Pike<br />

Agnes Plutino<br />

Wayne and Linda Porath<br />

Wayne and Elizabeth Porter<br />

George and Susan Powell<br />

Evelyn Presley<br />

Tom and Brenda Priesendorf<br />

Lowell Pugh<br />

Allan Puplis<br />

Lyle Pursell<br />

Phil Raithel<br />

Michael and Sharon Rapp<br />

Betty Rawley<br />

David Read<br />

Jerry Reese<br />

Steve Remspecher<br />

Rochelle Renken<br />

Bart and Liz Renkoski<br />

Barbara Reynolds<br />

Tom and Shirley Rheinberger<br />

Brenda Richards<br />

Margie Richards<br />

Sheryl Richardson<br />

Rose Rickard<br />

Joann Rickelmann<br />

Marcella Ridgway<br />

Mike Rieger<br />

Susan and Edward Robb<br />

Tim and Janet Rogers<br />

Alan Rolfing, DVM<br />

Robert Rothrock<br />

Gail Rowley<br />

Roy and Mary Ruckdeschel<br />

Ron Rupp<br />

James Ruschill<br />

Mark and Suzanne Russell,<br />

Cedar Bluff Farm<br />

Linda and Guy Sachs<br />

Charles Salveter<br />

Douglas and Jeanette Salzman<br />

Harlan Samuels<br />

Ken Schaal<br />

Francis and Eva Schallert<br />

Randy Scheffler and Janet<br />

Hankins<br />

Jim Schiller<br />

Pamela Schnebelen and<br />

Jane Anton<br />

Dave and Angela Schneider<br />

Gary Schneider<br />

Marc and Debbie Scholes<br />

Walter Schroeder<br />

Scott and Elizabeth Schulte<br />

Lynne Scott<br />

Eric Seaman<br />

Vincent and Joan Seiler<br />

Donna Setterberg<br />

Gary and Penny Shackelford<br />

Quint Shafer<br />

Jack Sharkey<br />

Terry Sharpe<br />

Robert Shelby<br />

Terry Shelton, Walnut Dell<br />

Farms, LLC.<br />

Michael Sherraden<br />

Sherry McCowan<br />

William Shields<br />

Joshua and Vonda Shoop<br />

Ross Shuman<br />

Mark and Sherry Siegismund<br />

Erin Skornia<br />

Robert and Joyce Slater<br />

Pittsburg State University<br />

Axe Library<br />

Mike Smith and Maria<br />

Brady-Smith<br />

Neal Smith<br />

Robert Smith<br />

Scott Smith<br />

Shaun Smith<br />

Steven and Julie Snow,<br />

Snow Family Farm<br />

Michael Soltys<br />

Herb and Charlene Sommerer<br />

Karen Stair<br />

Kathryn Steinhoff<br />

Doug and Cindy Steinmetz<br />

Family Steinmeyer<br />

Barbra Stephenson<br />

Kristina Sterling<br />

D’Jeanne Stevens<br />

Frank Stokes<br />

Al and Linda Storms<br />

Mark Strothmann<br />

Betty Struckhoff and James<br />

Harris<br />

Bob Sullivan<br />

Harriett Swinger<br />

Bernard and Betty Teevan<br />

Harold Temme<br />

Larry and June Terrell<br />

Alan Thibault<br />

Kathy Thiele<br />

Andrew and Diann Thomas<br />

Bob Thompson<br />

Thomas Thompson<br />

Romie Thornhill<br />

Dorothy and Robert Thurman<br />

Ed and Mary Tillman<br />

Michael Trial<br />

Robert Turnbull<br />

Aaron and Tracy Twombly<br />

Karen Van Berkel<br />

Elmer Van Dyke<br />

Barbara Van Vleck<br />

Charlotte VanBibber<br />

Leslie and James Vanluvan<br />

Joe Veras<br />

Adrienne Waterston and<br />

Tim Jegla<br />

Missouri Western State College<br />

Library<br />

Fred and Jan Weisenborn<br />

Charlene Wenig<br />

Patricia and Tom Westhoff<br />

Ann Wethington<br />

Bonnie and Timothy White<br />

Gail and Stephen White<br />

John White<br />

Kevin Whitsitt<br />

Mary Jo Wickliff<br />

Jerry and Maggie Wiechman<br />

Ashley Williams<br />

James and Marsha Wilson<br />

Elizabeth Winters-Rozema<br />

Michael Wohlstadter<br />

Dennis and Katherine Woldum<br />

Robert Wood<br />

P. Allen Woodliffe<br />

Chris Woodson<br />

Jean Worthley<br />

Suzanne Wright<br />

S. Jeanene Yackey<br />

George and Kay Yatskievych<br />

Judy Yoder<br />

James Zellmer<br />

Suzanne and Ted Zorn<br />

Mark Zupec<br />

To $34<br />

Katie Aichholz<br />

Irving and Melody Boime<br />

Stephen Bowles<br />

George and Nancy Brakhage<br />

Kevin and Evia Carpenter<br />

Robert Casner<br />

Judith Conoyer<br />

Liz Copeland<br />

Duane and Connie Dassow<br />

Bernadette Dryden<br />

Joe and Betty Dwigans<br />

Marshall and Faye Dyer<br />

Lisa Francis<br />

Sally and Howard Fulweiler<br />

Joseph Godi<br />

Jim and Betty Grace<br />

John Gulla<br />

Ron and Jan Haffey<br />

Winifred Hepler<br />

David and Jane Hooper<br />

Ann Korschgen<br />

Jean Kuntz<br />

Clarence Mabee<br />

Mid-Continent Public Library<br />

North Independence Branch<br />

Library<br />

Lyn Magee<br />

L. Margaret Martin<br />

Richard Matt<br />

Robert and Patricia McHenry<br />

Charles McDowell<br />

Marianne McGrath<br />

Thomas Metcalf<br />

Bob Middleton<br />

Bob and Phyllis Miller<br />

Rick Myers<br />

John Nekola<br />

Justin Newman and Elizabeth<br />

Leis-Newman<br />

Joyce Oberle<br />

William Piper<br />

Nancy and Sam Potter<br />

Gopinath Rao and Valerie Pod<br />

Betty Richards<br />

Gilbert and Donna Ross<br />

Robert and June Silverman<br />

Rollin and Bettina Sparrowe<br />

Cheryl Ann Steffan<br />

Dave and Mary Sturdevent<br />

Boyd and Carolyn Terry<br />

M. A. and J. A. Thomas<br />

Margaret Tyler<br />

Peter Van Linn<br />

Carl Wermuth and Carmen<br />

Cortelyou<br />

Woodneath Branch Library<br />

Contributions listed above are<br />

per 2013 bank deposit dates.<br />

Please contact Jane Schaefer,<br />

who administers MPF’s membership<br />

and donor database, at<br />

janeschaefer@earthlink.net or<br />

call 888-843-6739 if you have<br />

questions.<br />

* 2013 Crawford and Christisen<br />

Society members. Members of<br />

this society are existing lifetime<br />

members who give $1,000 or<br />

more in a year.<br />

MPF Receives Gift of $316,205 from the Linden Trial Estate<br />

Richard Day<br />

In 2013, MPF was honored to receive a very generous gift of $316,205<br />

from the estate of Ms. Linden Trial, of Columbia, who died in 2012 at<br />

the age of 61. In 2012, MPF also received $239,059 from Ms. Trial’s<br />

estate, bringing her total gift to MPF to $555,264.<br />

The bulk of Ms. Trial’s gift will be used to purchase and steward a new<br />

prairie acquisition; a small remainder will be used for outreach and education<br />

purposes. A modest amount was used in 2013 to fund a grassland dragonfly<br />

and damselfly study.<br />

Ms. Trial was an entomologist who worked for the Missouri<br />

Department of Conservation from 1972 until her retirement in 1999. She<br />

spent her first years on benthic entomology projects and specialized in<br />

adult dragonfly research during the last third of her working years. An avid<br />

field researcher, Ms. Trial discovered the rare Hine’s emerald dragonfly in<br />

Reynolds County, MO in 1999. Her contributions to dragonfly data are<br />

widely used in both state and national conservation projects.<br />

MPF is extremely grateful for Ms. Trial’s generosity and interest in<br />

prairie conservation.<br />

Vol. 35 No. 1 Missouri Prairie Journal 11

Prairie Strips<br />

Bringing biodiversity, improved water<br />

quality, and soil protection to agriculture<br />

By Lisa Schulte Moore<br />

The prairie strips conservation practice harnesses the<br />

productivity, stability, and benefits of prairie—the<br />

historically dominant ecosystem that once blanketed<br />

much of the Midwest—to help farms produce clean<br />

water, wildlife, and biological wonder in addition to<br />

food, feed, fiber, and fuel.<br />

The motivation for expanding the<br />

basket of goods that Midwestern farms<br />

produce is strong. While our current<br />

agricultural system achieves record productivity<br />

in crops and livestock, it is also<br />

associated with serious environmental<br />

shortcomings, including declines in<br />

water quality and biodiversity, increased<br />

flooding and greenhouse gas emissions,<br />

and even degradation of the foundation<br />

of agricultural productivity: the soil.<br />

Even tried and true conservation<br />

practices, like no-till, are recognized to<br />

be insufficient given the heavy rains the<br />

region is now commonly experiencing.<br />

Many farmers, farmland owners, and<br />

conservation professionals are recognizing<br />

that we need a better way. Prairie<br />

strips might just be that better way for<br />

some farms.<br />

12 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 1

Sarah Hirsh<br />

The Prairie Strips Practice<br />

A prairie strip is an area within or at the<br />

downslope edge of a crop field that has<br />

been planted to and managed as native<br />

prairie vegetation. The prairie strips<br />

practice was developed and monitored<br />

in an experiment at central Iowa’s Neal<br />

Smith National Wildlife Refuge. The<br />

STRIPS acronym stands for “Strategic<br />

Integration of Rowcrops with Prairie<br />

Strips.”<br />

Prairie strips may vary in width and<br />

length based on the characteristics of<br />

the field, including its topography, soil<br />

type, and size. Importantly, the strips<br />

are interlaced with crops and follow the<br />

topographic contour so they intercept<br />

water running over the soil surface. Also<br />

importantly, the strips are planted to<br />

a diverse mix of native prairie plants,<br />

including cool-season grasses, warm-season<br />

grasses, and forbs. This diverse mix<br />

of prairie plants, with their stiff, upright<br />

stems, deep roots, and biological activity<br />

over the course of the whole growing<br />

season, provide ecological functions that<br />

annual crop plants—which are designed<br />

to maximize grain or bean productivity—do<br />

not.<br />

In 2007, the STRIPS team—<br />

including investigators from Iowa State<br />

University, the USDA Agricultural<br />

Research Service, the U.S. Fish and<br />

Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Forest<br />

Service—sowed the seeds of 35 native<br />

prairie plant species in 10- to 30-footwide<br />

strips (100- to 150-feet-wide at<br />

slope base) in experimental catchments<br />

farmed on a corn-bean rotation using<br />

no-till techniques. The experiment tested<br />

four different configurations:<br />

• all row crop (no prairie)<br />

• 90 percent row crops and 10 percent<br />

prairie placed all at the bottom of the<br />

catchment where runoff water flows out<br />

• 90 percent row crops and 10 percent<br />

prairie placed in multiple strips running<br />

along the contour<br />

This prairie strip is part of the STRIPS experiment at Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge, Prairie<br />

City, Iowa. The diverse native prairie plants with stiff stems and deep roots make this practice<br />

effective at providing multiple conservation benefits, including erosion control, clean water, and<br />

wildlife and pollinator habitat.<br />

• 80 percent row crops and 20 percent<br />

prairie placed in multiple strips running<br />

along the contour.<br />

Slopes at our experiment range<br />

between 6 and 10 percent. We also<br />

installed many kinds of scientific monitoring<br />

equipment in these catchments so<br />

we could quantitatively understand how<br />

these areas were functioning agronomically<br />

and environmentally. Specifically,<br />

we measured crop yield, soil and water<br />

movement, plant cover and diversity,<br />

bird and insect diversity, greenhouse gas<br />

emissions, and socioeconomic characteristics.<br />

A catchment is a topographically defined area<br />

of land that basically “catches” rainfall. Any<br />

rainfall, minus that which evaporates or is<br />

transpired by plants, should theoretically run<br />

toward and congregate at the lowest spot in<br />

the catchment. This experimental catchment,<br />

above, contains alternate strips of prairie<br />

and crops, in this case soybeans. An H-flume<br />

is located at the bottom of the catchment<br />

and allows collection of samples of water<br />

runoff. The poles protruding from the strips<br />

mark the location of ground water wells, for<br />

measuring ground water depth and chemistry,<br />

and suction cup lysimeters, for measuring soil<br />

water chemistry.<br />

Anna MacDonald<br />

Anna MacDonald<br />

Vol. 35 No. 1 Missouri Prairie Journal 13

Here are some of our results:<br />

• In terms of plant measures, we find<br />

that catchments that have at least 10<br />

percent of their area in prairie have a<br />

380 percent increase in native plants<br />

with 115 percent cover compared to<br />

entirely row-cropped catchments. This<br />

is impressive, but not surprising, given<br />

we planted most of this diversity.<br />

• Important to farmers who might adopt<br />

prairie strips as a conservation practice,<br />

we’ve also found that the strips do<br />

not have a negative impact on yield of<br />

adjacent crops, and plants from them<br />

do not invade adjacent cropland. In<br />

other words, the prairie plants do not<br />

become a weed problem for farmers.<br />

• Our data on water quality impacts are<br />

probably the most dramatic. We’ve<br />

recorded 60 percent less water leaving<br />

catchments with just 10 percent of<br />

their area in prairie strips, likely due to<br />

the combination of greater infiltration<br />

of water through the soil and transpiration<br />

of water to the atmosphere by the<br />

prairie plants. Associated with lower<br />

levels of runoff are 95 percent reductions<br />

in the amount of sediment moving<br />

out of the catchments, and nearly<br />

90 percent reductions in the amount<br />

of phosphorus and nitrogen moving<br />

out of the catchments. These measures<br />

are important because while soil,<br />

phosphorus, and nitrogen are wonderful<br />

assets supporting plant growth in<br />

agriculture fields, they become serious<br />

pollutants if they reach our waterways.<br />

Sediment, phosphorus, and nitratenitrogen<br />

are three of the top four water<br />

pollutants in Iowa. In Missouri, bacteria<br />

is the most common water pollutant,<br />

followed by heavy metals.<br />

• Soil is an invaluable farm resource.<br />

Our data show that, on sloping lands<br />

like at our experimental location, notill<br />

soil management alone was not<br />

adequate for keeping soil loss below<br />

USDA Natural Resource Conservation<br />

Service’s “tolerable soil loss” of 5 tons<br />

per acre per year. In one April 2009<br />

storm alone, an average of 1 ton per<br />

acre of soil was lost from catchments<br />

without strips; loss from catchments<br />

with 10 percent in prairie strips was<br />

negligible. No-till needs to be considered<br />

a component of a conservation<br />

system that also include other conservation<br />

practices such as prairie strips,<br />

grassed waterways, and cover crops.<br />

• In terms of beneficial insects, we’ve<br />

recorded the same diversity of insect<br />

pollinators as found in nearby patches<br />

of restored prairie. We’ve found 1.4<br />

to 2 times the abundance of insects<br />

that serve as predators of crop pests in<br />

prairie strips than in adjacent cropland.<br />

While the strips appear to be providing<br />

habitat for these beneficial species, we<br />

have not yet detected a reduction in<br />

crop pests as a result.<br />

• With regard to bird biodiversity, we’ve<br />

recorded 118 percent and 133 percent<br />

increases in native bird species richness<br />

and abundance, respectively, including<br />

species of regional and continental<br />

conservation concern, including the<br />

field sparrow, lark sparrow, and dickcissel.<br />