Download PDF Version Revolt Magazine, Volume 1 Issue No.4

Download PDF Version Revolt Magazine, Volume 1 Issue No.4

Download PDF Version Revolt Magazine, Volume 1 Issue No.4

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

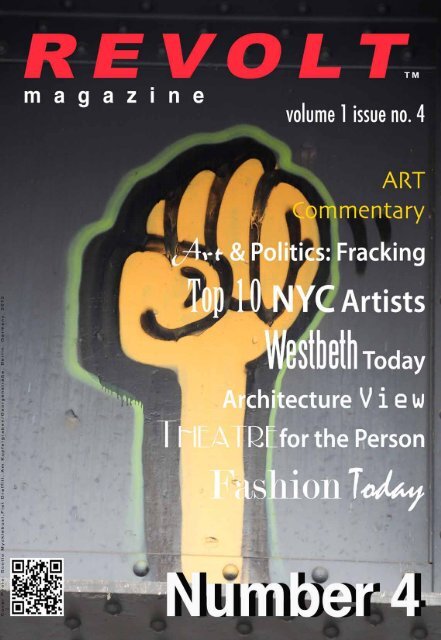

m a g a z i n e<br />

TM<br />

volume 1 no. 4 • 2013<br />

REVOLT is:<br />

PUBLISHED BY:<br />

Public Art Squad Project<br />

PUBLISHER: Scotto Mycklebust, Artist<br />

MANAGING EDITOR: Katie Cercone<br />

CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Scotto Mycklebust<br />

ART & DESIGN: Scotto Mycklebust<br />

ART PHOTOGRAPHER: Scotto Mycklebust<br />

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Dan Callahan,<br />

Linda DiGusta, Laurence Hoffmann, Emily<br />

Kirkpatrick, Rob Reed, Suzanne Schultz,<br />

Randee Silv, Adam Laten Wilson, Lena Vazifdar<br />

ADVERTISING CONTACT:<br />

advertise@revoltmagazine.org<br />

SUBMISSIONS:<br />

submission@revoltmagazine.org<br />

DONATIONS:<br />

donation@revoltmagazine.org<br />

CONTACT us:<br />

REVOLT OFFICES:<br />

West Chelsea Arts Building<br />

526 West 26th Street, Suite 511<br />

New York, New York 10001<br />

212.242.1909<br />

ON THE WEB:<br />

www.revoltmagazine.org<br />

info@revoltmagazine.org<br />

ON FACEBOOK:<br />

www.facebook.com/revoltmagazine<br />

FOR EDITORIAL INQUIRIES:<br />

editorial@revoltmagazine.org<br />

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST:<br />

subscribe@revoltmagazine.org<br />

REVOLT<br />

ARTISTS MUSEUM<br />

www.revoltmagazine.org<br />

REVOLT<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong> Number 4, 2013<br />

Letter from the Publisher ...<br />

For the fourth issue of <strong>Revolt</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> we’re<br />

pleased to announce the addition of our new Theatre<br />

View section, where you’ll be able to read up on the<br />

latest approaches to art on the stage. This month’s<br />

Theatre View featured article by Adam Latten Wilson<br />

“Theatre for the Person: Two Perspectives,” explores<br />

theater as a device to promote social change. We’ve<br />

also published a review of folklorist Kay Turner’s<br />

“OTHERWISE: Queer Scholarship into Song.” Going<br />

forward, we’ll include new works from playwrights<br />

in addition to ample reviews and critical theater<br />

dialogue.<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 4 also features a new section on Architecture,<br />

kicked off by an interview with the Danish-Czech<br />

contemporary artist-architect Therese Himmer, who<br />

details her recent public work in Russia and talks<br />

about nomadic subjectivity and the semiotics of<br />

space.<br />

For a look at today’s fashion, contributing writer<br />

Emily Kirkpatrick walks us through the ample<br />

closet of the First Lady to explain how and why the<br />

“Media’s Fetishistic Gaze” still relegates powerful<br />

IN THIS ISSUE:<br />

4 Social Activism in Fancy Tones<br />

6 The Gallery Review<br />

8 The Rose Unearthed<br />

12 Top 10 NYC Artists Now<br />

14 The Cult of the First Lady<br />

20 Westbeth Artists' Community Housing<br />

26 Fracking: Drawing the Line<br />

29 Cinema Review<br />

30 The Literary View<br />

32 Theatre View<br />

36 Architecture View<br />

39 The <strong>Revolt</strong> Takes Boston<br />

40 2 Tha Beat Y'all<br />

44 Swagilish Salomom and TheiLLUZiON<br />

women like Michelle Obama to the shallow periphery<br />

of public discourse.<br />

On the activist front, writer Linda DiGusta details<br />

the fierce and passionate dedication of a growing<br />

number of visual artists dedicated to combating<br />

Fracking.<br />

On the topic of Art and Community Lena Vazifdar<br />

reports on the Westbeth artist community housing<br />

project, which has thrived in Manhattan’s West<br />

Village since 1970.<br />

For our Gallery view section Randee Silv reviews The<br />

Jay Defeo Retrospective at the Whitney. And lastly,<br />

part of her ongoing interdisciplinary inquiry into the<br />

Spirituality of Hip Hop, REVOLT Editor Katie Cercone<br />

publishes a pair of related articles including field<br />

notes from the global Hip Hop Pedagogy movement,<br />

and a roundtable discussion with the REALEST upand-coming<br />

new age hip hop crew TheILLUZiON.<br />

What’s their code?: Love/Faith/Gratitude/Harmony.<br />

Scotto Mycklebust<br />

MISSION STATEMENT<br />

Through a diverse array of journalistic styles - investigative, academic, interview,<br />

opinion - and stunning visuals, REVOLT <strong>Magazine</strong> aims to ensure that art never loses<br />

its profundity. We urge our readers to join our mission, generating positive social<br />

change through creative production and informed cultural critique.<br />

Copyright & Permissions Info: © copyright 2011, 2012, 2013 <strong>Revolt</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>. All Rights Reserved. For all<br />

reprints, permissions and questions, please contact 212.242.1909 or by email: info@revoltmagazine.com.<br />

2

Hôtel<br />

AMERICANO<br />

Chelsea<br />

New York<br />

518 West 27 th Street, New York NY 10001<br />

For booking<br />

hotel-americano.com 212.216.0000

THE<br />

R LIST<br />

Social Activism in fancy Tones<br />

On how celebrities engage to improve contemporary society<br />

BY LAURENCE HOFFMANN<br />

Promoting oneself is commonly accepted, if not<br />

practiced, by people in all strata of society. Individuals<br />

are more and more managing themselves as<br />

brands, a trend put in motion by social media like<br />

Facebook and Twitter, that heightens the need to<br />

make an original mark in a world over-crowded with<br />

competing information. On the business side this<br />

applies to advertisements, which effectively use<br />

celebrities to create instant familiarity through the<br />

immediate recognition of a particular celebrity’s<br />

brand.<br />

Recently self-branding has taken a new turn as<br />

more popular figures have applied their massmarket<br />

appeal to serious social issues. A cursory<br />

list of examples includes Mark Ruffalo and Yoko<br />

Ono with son Sean Lennon opposing fracking<br />

with Artists Against Fracking; Joaquin Phoenix<br />

defending the rights of people and animals together<br />

with -respectively- Amnesty International and<br />

Peta; Leonardo Di Caprio trying to prevent total<br />

degradation of the environment with Live Earth<br />

and Wildlife Conservation Society; Ziggy Marley,<br />

Lady Gaga, Linkin’ Park, BBKing and others making<br />

efforts to bring music education into disadvantaged<br />

public schools with Little Kids Rock; George Clooney<br />

is one of the United Nations Messengers Of Peace<br />

and together with Brad Pitt, Matt Damon, Don<br />

Cheadle and others has founded Not On Our Watch<br />

to condemn the violations of human rights in Darfur,<br />

Burma, and Zimbabwe; Angelina Jolie is Special<br />

Envoy for the United Nations. These are just a few<br />

of the causes in which some of the most prominent<br />

American stars emerge as “social activists” and in<br />

some cases as “social entrepreneurs”.<br />

For his activities (other than being Walden Smith in<br />

Two and a Half Men and occasionally appearing on<br />

the cover of magazines with old and new flames)<br />

Ashton Kutcher can be considered a “social<br />

entrepreneur”. The business activities of his<br />

company A-Grade are geared towards improvements<br />

in contemporary society.At TechCrunch, an event<br />

that focuses on start-up companies keen to enter<br />

the field of technology development and new media<br />

held in April/May in NYC, Ashton Kutcher explained<br />

the criteria behind the investments of A-Grade and<br />

revealed his critical take on corporations.<br />

Ashton Kutcher, Guy Oseary, and Michael Arrington, TechCrunch Disrupt NYC 2013, video stills. Courtesy of Laurence Hoffmann.<br />

With his notorious sardonic language typical to an<br />

“agent provocateur”, he decries the concept of<br />

Big Brother. He warns that societies should prefer<br />

the decentralization of the security system instead<br />

of accepting that one major entity controls the<br />

masses. Ashton proposes that security should be<br />

based on the interaction among individuals. This<br />

critical approach defines an optimistic point of view<br />

on local communities built by the genuine personal<br />

relationships between people. Such conviction<br />

For his eclectic interests and activities, Ashton<br />

belongs -together with all socio-politically engaged<br />

celebrities- to that figure so much in vogue in the<br />

Renaissance, “the Renaissance Man”. In the 15th<br />

and 16th Centuries the reevaluation of the models<br />

from Antiquity took an important step. Artists<br />

and philosophers were called to court (royalty,<br />

aristocracy or new bourgeoisie) to engage into the<br />

political discourse and became spokes persons,<br />

aka ambassadors. What made them “Renaissance<br />

implies a strong criticism towards the general Men” was their versatility in various fields of culture,<br />

opinion that our western (and newly BRIC) societies science, politics and the conviction that societies<br />

are tending towards a more anonymous global could harmonically entail all these aspects. These<br />

system.<br />

societies were literally called Utopia, a term that<br />

today has taken on the connotation of “illusionary<br />

On the practical business level, Ashton focuses and unrealistic”.<br />

on financially supporting and strengthening<br />

technological platforms that enhance social sharing. This lead to an open conclusion: Is social activism<br />

And since interconnectivity is fundamentally an in all its forms a sheer idealistic endeavor or can<br />

element of mutual trust, it is especially through<br />

social media that a stronger connection between<br />

the contribution of mass mediated personae really<br />

reach the masses and help make the change?<br />

individuals can be achieved and local communities<br />

are therefore spontaneously formed.<br />

REVOLT<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong> Number 4, 2013<br />

4

THE<br />

GALLERY<br />

VIEW<br />

BY ROB REED<br />

AL HELD<br />

Alphabet Paintings<br />

Fedruary 28 - April 20, 2013<br />

Cheim & Read<br />

547 West 25th Street NY, NY<br />

Tension and play were a couple of Al Held's guiding<br />

forces in creating the Alphabet Paintings that Cheim<br />

& Read in Chelsea presents. All made between<br />

1961 and 1967, the monumentally scaled acrylics<br />

on canvas take their queue from letter forms – a<br />

technique for composing and dividing abstracted<br />

space that retains also a sense of visual familiarity<br />

that would otherwise be lost in purely minimalist<br />

works. Typography, here, offers the artist a heuristic<br />

that yields surprising results without ever slipping<br />

into alienating territory.<br />

Held used both serif and sans-serif typefaces,<br />

and in works with letters as titles, he isn't merely<br />

transposing and cropping letter forms. In "The 'I,'" for<br />

example, the white vertical bars flanking the sides<br />

are indeed the spaces created between the capital<br />

letter's top and bottom serif. The white bars are<br />

not true to form, however; they're shortened, and<br />

angled slightly more than 90 degrees, which builds<br />

compositional tension and holds the shapes in.<br />

Thus, the black and white work is strikingly modern<br />

without feeling cold.<br />

Turning to letters themselves, consider that the<br />

quintessentially modern typeface Helvetica – it's<br />

now used by Apple, American Apparel, and even the<br />

MTA subway system – was designed just four years<br />

prior to the earliest painting in this exhibition, "Ivan<br />

the Terrible," 1961. Modern is synonymous with<br />

stripping forms of ornament, and with ornament<br />

goes sentiment. But for all of Held's paring down,<br />

he packs emotion back in with intense color,<br />

compositional skewing, and, at least in the "X"<br />

paintings, thwarting of linear perspective.<br />

In the back exhibition room is "The Yellow X," 1965.<br />

The second largest piece in the exhibition, its content<br />

is true to its title. The power of the yellow hue is<br />

nearly overwhelming as it bounces off the adjacent<br />

walls and fills the room. Lost in some reproductions,<br />

however, is not only the work's scale, but the center<br />

divide where the diptych merges and creates a black<br />

sliver that slices the X rather dramatically.<br />

The Alphabet Paintings prefigure the "abstract<br />

illusionism" developed in Held's later works by<br />

tweaking recognizable shapes. Without all the<br />

overlaps, three-dimensionality, and spatial depth<br />

that dominate the latter-day paintings we more<br />

closely associate with Held, these works have an<br />

eccentric iconicity all their own.<br />

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT<br />

February 7 - April 6, 2013<br />

Gagosian Gallery<br />

555 West 24th Street NY, NY<br />

It's nearly impossible to respond to the paintings<br />

of Jean-Michel Basquiat unencumbered by what<br />

history has made of him, or even, for that matter,<br />

what he made of himself. Yet the voracity of the<br />

artist's ego and that of the 1980s art market is<br />

essential to appreciating how the artist worked and,<br />

frankly, how much art he was able to make – roughly<br />

1000 paintings and 2000 drawings in the seven<br />

years before his death of a drug overdose at the<br />

age of 27. (Without a stream of collectors, where do<br />

3000 pieces of art go?) This inseparability of man<br />

and market can translate to an irreducibility that<br />

makes either severe criticism of his work or effusive<br />

eulogizing a bit inadequate.<br />

Gagosian Gallery's Chelsea location offers a unique<br />

opportunity to mine Basquiat's oeuvre through over<br />

50 works drawn from private and public collections.<br />

A curatorial theme isn't obvious if it's here. The<br />

exhibition rooms' large sizes, however, create ample<br />

space for incongruities to commingle without much<br />

fuss. And incongruities, disparities, and stream-ofconsciousness<br />

pastiche are what make Basquiat's<br />

art what it is.<br />

Among the metaphors Basquiat assumed for his<br />

persona is the boxer. We've all seen the black<br />

and white posters of Basquiat and Andy Warhol in<br />

boxing gloves, as if ready to spar. The boxer asserts<br />

Basquiat's aggressive rounds with the art world,<br />

and perhaps – at least in the portrait series of<br />

black boxers, including Jack Johnson, Sugar Ray<br />

Robinson, Cassius Clay, etc. – a critique of the art<br />

world's racial makeup (though this he denied).<br />

Al Held (1928 - 2005), IVAN THE TERRIBLE, 1961. Acrylic on canvas 144 x 114 inches 365.8 x 289.6 centimeters CR# He.31324<br />

Photos courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.<br />

REVOLT<br />

The "boxer series" contains some of the most<br />

inventive works, essentially bricolage, seductively<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong> Number 4, 2013 6

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, Untitled (Two Heads on Gold), 1982, Acrylic and oil paintstick on canvas, 80 x 125 inches, (203.2 x 317.5 cm). Photos courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York.<br />

unusual in appearance and clever in their material<br />

combinations. "Cassius Clay," 1982, is an acrylic<br />

and oil stick on canvas; however, the stretcher is a<br />

found wood pallet which creates rounded edges on<br />

the top and bottom, lifted in the center by the pallet's<br />

vertical stringer. Half sculpture, half painting, these<br />

works have a presence that humorously undermines<br />

modern painting and how "high art" ought to look.<br />

Toward the end of his short life, Basquiat's paintings<br />

began to empty out with a haunting fatigue. "Riding<br />

with Death," 1988, is one of the most poignant. A<br />

man, red, rides the barely joined bones of a crawling<br />

skeleton, perhaps his own, in an empty bronze field.<br />

The metallic sheen gives the work a royal dignity as<br />

if the artist had unwittingly bestowed his own last<br />

rites.<br />

with prismatic projections emitted from the eyes<br />

and lips making diamonds in the painting's center.<br />

The symmetry, simplicity, and complimentary colors<br />

of dark blue and orange make the 26-inch square<br />

piece feel iconic.<br />

Geoff McFetridge's medium-sized painting "12<br />

Dots," 2013, depicts twelve individuals from a<br />

bird's eye view. Their heads, each a black circle,<br />

and bodies with limbs are choreographed in a cool<br />

palette of grays, blues and whites, punctuated by a<br />

red shirt or two. The graphic, almost mechanical,<br />

quality of the composition gives the image a slick<br />

iciness, especially since no eye contact is being<br />

made either inside or outside the painting.<br />

Ryan Schneider's "How Long Have You Known?,"<br />

2013, shares a palette similar to Oinonen's, yet it's<br />

more saturated and high-keyed. A topless woman<br />

sunbathes, only partly shaded by palm leaves,<br />

on a red-and-black striped towel with various<br />

fruits around her. As the towel and fruit appear<br />

atilt, leaning unnaturally forward, the painting's<br />

lower half feels like a Matisse still life. It's a nice<br />

effect, even if the crotch-centric composition (and<br />

exaggerated signature) is a tad heavy handed. At the<br />

same time, overstatement seems to authenticate<br />

contemporaneity these days.<br />

Fifty years ago artist-critic Fairfield Porter reviewed a<br />

MoMA exhibition "exploring recent directions in one<br />

CHICKEN OR BEEF?<br />

March 6 - April 20, 2013<br />

The Hole<br />

312 Bowery, NY, NY<br />

If you're "crossing the pond," as international<br />

travelers phrase it, the flight attendant's question<br />

at mealtime could be "Chicken or beef?" Hence the<br />

title of The Hole's mini-survey exhibition of figure<br />

paintings drawn from artists mostly in Europe<br />

and North America. There's no real premise here.<br />

The press release alludes to connecting threads,<br />

but the pleasure in the show is in the disparity of<br />

approaches to representation sustained by an<br />

evenness in quality.<br />

Several artists are widely known, such as Cecily<br />

Brown, Barnaby Furnas, and Jules de Balincourt. The<br />

latter employs a Rubin vase motif (i.e., two facing<br />

silhouettes that make, by illusion, a center vase)<br />

Xstraction: A survey of new approaches in abstraction, installation view. Photos courtesy The Hole, New York.<br />

One knockout piece is "Unopposite," 2012, by aspect of American painting: the renewed interest<br />

Canadian-based artist Anders Oinonen. Keen in the human figure." A figure painter himself, he<br />

sensibilities of abstraction and figuration arise in quickly pointed out that "[s]ince painters have<br />

equal measure in one large saddened, upwardgazing<br />

face. Painted in bright, fine-tuned pastels to represent a renewed interest in the figure on the<br />

never stopped painting the figure...it could be said<br />

strategically modified with angled planes that part of critics and the audiences rather than among<br />

function like scrims or thin white washes, the sevenfoot-tall<br />

painting appears to genuinely emote, albeit painters." I'd like to think that's still true.<br />

painters. To this extent the critics are following the<br />

in a cartoonish way – which is surprising given how<br />

rigorously abstract its composition is.

BETWEEN DESTINATIONS:<br />

THE ROSE<br />

UNEARTHED<br />

BY RANDEE SILV<br />

After circling through the 4th floor galleries at the<br />

Whitney Museum, I found myself returning to the<br />

same exact spot at Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective<br />

(February 28 - June 2, 2013). It was like being<br />

caught in a visual net as my glance slightly turned<br />

in both directions. I couldn’t move as I stood there<br />

between DeFeo’s seven foot wide hypnotic graphite<br />

on paper, The Eyes (1958), and the monumental,<br />

nearly one ton, The Rose (1958-66), nestled<br />

in the small sanctuary that the museum had<br />

designed to emulate the sunlight as it streamed<br />

into her Fillmore Street studio. DeFeo always felt<br />

that this drawing had something of a “prophetic<br />

or visionary meaning,” and it was through these<br />

eyes that her works to come would be envisioned.<br />

Her desire was that some day these two pieces<br />

would be shown together. I could almost hear them<br />

conversing. Unexpectedly, I was drawn in.<br />

Jay DeFeo was a painter among the ‘50s San<br />

Francisco scene of artists, poets and jazz<br />

musicians. After graduating from the University of<br />

California at Berkeley with a master’s degree, she<br />

was awarded a traveling fellowship that no woman<br />

had yet received. Knowing this, the art department<br />

strategically recommended her as J. DeFeo. She<br />

then spent a year and a half in Europe and North<br />

Africa before settling in Florence for 6 months.<br />

Intrigued by ordinary objects, astronomy, unspoken<br />

subjects, erasures, Italian architecture, jagged<br />

mountain peaks, Asian, African & prehistoric art,<br />

DeFeo dynamically meshes her own rhythms and<br />

forms.<br />

Dorothy Miller, the curator and director of the<br />

Museum of Modern Art, who happened to be out<br />

talent scouting, saw DeFeo’s first one-person<br />

show at the Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco. Miller<br />

visited DeFeo’s studio and was hoping to include<br />

The Rose (entitled Deathrose at that time) in the<br />

upcoming 1959 landmark exhibition, Sixteen<br />

Americans (December 16, 1959 - February 17,<br />

1960). Holding out for a showing on the West<br />

Coast, DeFeo hesitated about parting with her<br />

work still in progress. Five other pieces were<br />

chosen, and a reproduction of the unfinished<br />

Deathrose was published in the accompanying<br />

catalogue. DeFeo and her husband, Wally<br />

Hendricks, decided to turn down the plane tickets<br />

bought by MoMA for the opening. Hendricks, who<br />

was also invited to be in the exhibition, was known<br />

for his kinetic assemblages and was co-founder<br />

of The Six Gallery, an underground art gallery and<br />

hang for Beat poets.<br />

“Wally and I didn’t really realize the stature and the<br />

prestige of being included in such a show. I was<br />

really unaware of the situation. It surprises many<br />

people that we were the only people included<br />

in the show who didn’t make the effort to go<br />

back for the opening. The whole show was kind<br />

of a coming-out party, I discovered later. It was<br />

intended to be for galleries in search of new talent.<br />

I was approached by the Stable Gallery through<br />

correspondence, which I turned down.”<br />

New York Times critic, John Canaday wrote “For my<br />

money, these are the sixteen artists most slated for<br />

oblivion.” Included in the show were Jasper Johns,<br />

Robert Rauschenberg, Louise Nevelson, Ellsworth<br />

Kelly and Frank Stella.<br />

Having found herself on an unplanned journey that<br />

engulfed and obsessed her for eight years, DeFeo<br />

devoted herself intensely to painting, layering,<br />

sculpting, working and reworking Deathrose.<br />

She repeatedly applied thick coats of white oil<br />

paint, using black to minimize the yellowing and<br />

occasionally mixing in mica for sparkle, while<br />

scraping, reapplying, working with thinness and<br />

thickness, allowing paint to dry and carving into<br />

the material with a palette knife. Extending the<br />

painting’s radiating lines from a study photograph<br />

in preparation to enlarge Deathrose, she drew<br />

and painted these extensions directly onto the<br />

supporting wall around the canvas, later removing<br />

her work from its stretcher bars, gluing it to a<br />

larger unprimed canvas and placing it in her front<br />

room bay window. More pigment was intuitively<br />

placed, reformatting the center, shaping hard<br />

edged grooves into smooth ridges and crevasses<br />

highlighting the sun’s rays, emphasizing shadows,<br />

observing proportions, contours, growing thicker<br />

and heavier with each stage as unpredicted<br />

surface textures kept emerging.<br />

Deathrose was extensively photographed in its<br />

many evolving phases. Images circulated even<br />

before its completion. One landed in a 1961<br />

Art in America article, “New Talent U.S.A.” That<br />

same year, the travel magazine Holiday included<br />

Deathrose in a piece “San Francisco: The<br />

Rebels.” DeFeo was the only painter mentioned<br />

and described as “one of San Francisco’s most<br />

successful younger artists.” The photograph of<br />

DeFeo working on Deathrose as she stood on a<br />

stepladder appeared in a 1962 issue of Look.<br />

News of her mammoth sculptured painting began<br />

spreading. Different institutions were thinking<br />

about how they might acquire Deathrose, but<br />

DeFeo had no intention of donating her work.<br />

DeFeo working on what was then titled Deathrose, 1960. Photograph<br />

by Burt Glinn. © Burt Glinn/Magnum Photos.<br />

In 1965, DeFeo and Hendricks ended up being<br />

evicted from their Fillmore studio when the building<br />

was condemned and new owners doubled the rent.<br />

Deathrose measured nearly 12’ x 8’ with depths in<br />

spots deeper than eight inches and had to be cut<br />

away from the studio wall, a crate built around it,<br />

lowered by forklift to a truck below and relocated<br />

to a small room for storage at the Pasadena Art<br />

Museum.<br />

Bruce Conner, friend, filmmaker, interdisciplinary<br />

REVOLT <strong>Magazine</strong> Number 4, 2013 8

artist, “Father of MTV,” conceptual prankster and<br />

founder of the Rat Bastard Protective Association,<br />

a group of Beat and Funk artists, felt that “This<br />

final form was not ever finished, it had to take<br />

an uncontrolled event to make it stop.” Conner<br />

documented this “transplant” in his 7 minute<br />

film, The White Rose (1967) Jay DeFeo’s Painting<br />

Removed by Angelic Hosts (1967), to the sounds of<br />

Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain.<br />

DeFeo stopped refining it three months later.<br />

Renamed from Deathrose which she thought “just<br />

a little melodramatic,” now to The White Rose,<br />

feeling “ the rose was so much an aspect of life as<br />

of death,” she eventually just went with The Rose,<br />

“the unity with both of those opposite ideas.”<br />

The Rose had its first public showing in 1969 at<br />

the Pasadena Art Museum, traveled to the San<br />

Francisco Museum of Art and was afterwards<br />

installed in the new wing at the San Francisco Art<br />

Institute, where it was bolted to a concrete wall in<br />

the McMillan Conference Room.<br />

“I had done absolutely nothing from the time I<br />

finished The Rose until 1970. I was repairing<br />

my personal life as well as my psyche after the<br />

heavy experience that the painting of The Rose<br />

was. I needed that time to restore some kind of<br />

equilibrium and gain some kind of perspective on<br />

my life’s work and get some feeling of what could<br />

naturally come after that.”<br />

With the emergence of Minimalist and Pop Art<br />

during the ‘60s, not seeing herself as part of the<br />

feminist movement and maybe being too tightly<br />

pegged as a “Beat” artist, DeFeo began feeling as<br />

if the art world had moved on and was showing<br />

little interest in her work. She bought a Hasselblad<br />

camera and immersed herself into photography.<br />

She continued to seek museum placement for<br />

The Rose. By 1972, it was showing signs of<br />

hair line cracks, nicotine grime, scratch marks,<br />

graffiti, coffee stains, loose chunks of paint, with<br />

the canvas sagging from its weight. DeFeo knew<br />

she’d have to find help to cover these now needed<br />

repairs. Conner screened his film, which had<br />

already helped to keep The Rose in the public eye,<br />

for grassroot fundraising campaigns. Events were<br />

organized. DeFeo received a $1,500 National<br />

Endowment grant. News about the The Rose<br />

resurfaced in the San Francisco press as they<br />

covered the story of DeFeo’s restoration efforts.<br />

The museum conservation team started to clean<br />

and repair The Rose, encasing it in a structure<br />

of wax, starch paste, polyvinyl acetate, packing<br />

material, mulberry tissue, cotton sheeting and<br />

plaster reinforced with chicken wire. Money ran<br />

out. A particle board wall was eventually built<br />

in front of it for student exhibitions. The Rose<br />

remained hidden for the next twenty years.<br />

As the art world “rediscovered” DeFeo, her new<br />

work began to see momentum by 1975 with a run<br />

of successful one-person shows that followed.<br />

Curatorial consultant Leah Levy joined her efforts<br />

The Rose, 1958–66, Oil with wood and mica on canvas, 128 7/8 x 92 1/4 x 11 in. (327.3 x 234.3<br />

x 27.9 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of The Jay DeFeo Trust, Berkeley, CA, and purchase with funds<br />

from the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee and the Judith Rothschild Foundation 95.170, © 2012 The Jay<br />

DeFeo Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Photograph by Ben Blackwell.<br />

to find a permanent home for The Rose. DeFeo<br />

took a teaching position at Mills College and<br />

climbed Mount Kenya, a lifelong dream.<br />

The Rose continued to remain an obscure mystery.<br />

After DeFeo’s death in 1989, The Jay DeFeo Trust<br />

was established and the search for a permanent<br />

location for The Rose continued. Would a museum<br />

take the risk of putting out money, not knowing<br />

if the painting was salvageable or not? DeFeo’s<br />

patrons and the “Friends of the Rose” were<br />

committed and determined. They felt deeply<br />

captivated and transformed by The Rose. They<br />

praised her as a true innovator. Her struggle had<br />

now become their own struggle to bring The Rose<br />

back to life.<br />

In 1992, Lisa Phillips, the Whitney Museum’s<br />

curator, contacted the estate about a possible loan<br />

of The Rose for their upcoming exhibition, Beat<br />

obviously in no condition to be shown. The estate<br />

contacted Lisa Lyons at the Lannan Foundation<br />

in Los Angeles for possible conservation support.<br />

J. Patrick Lannan had been an avid collector of<br />

DeFeo’s work and had originally wanted to buy the<br />

unfinished Deathrose, which he had nicknamed<br />

“The Endless Road.” Three small square windows<br />

were cut into the plaster covering, and, to<br />

everyone’s surprise, it hadn’t turned into “slime”<br />

or “goo” or become coated with mold. Two years<br />

later, the Lannan Foundation redirected its mission<br />

away from the acquisition of art.<br />

David Ross, director of the Whitney, told Levy,<br />

“It’s one of the greatest masterpieces of postwar<br />

American art. It had to be rescued.” The Whitney

acquired it and covered all restoration costs. Once<br />

again, The Rose was lowered through a window by<br />

crane onto a flatbed truck, taken to a warehouse<br />

for cleaning, where its air pockets were filled with<br />

epoxy mixed with chopped fiberglass. 1500 pounds<br />

heavier, it was shipped to New York City for the<br />

Beat Culture exhibition, thirty one years after its<br />

eviction from Fillmore street. The public could now<br />

experience The Rose as DeFeo had envisioned it. It<br />

was no longer an art world rumor.<br />

A color reproduction of The Rose landed on the<br />

cover of the March 1996 issue of Art in America.<br />

Bill Berkson’s article, In the Heat of The Rose,<br />

was featured. The Rose traveled to the Walker Art<br />

Center in Minneapolis, the M.H. de Young Memorial<br />

Museum in San Francisco and the Berkeley Art<br />

Museum. The Whitney Museum included The Rose<br />

in its 1999 exhibition, The American Century: Art &<br />

Culture 1900-2000, Part II and in the 2003 Beside<br />

“The Rose”: Selected Works by Jay DeFeo (October<br />

2, 2003 - February 29, 2004.)<br />

Shortly before Jay DeFeo died, she shared this with<br />

Leah Levy: “She is walking through a museum in<br />

her dream, but she is not Jay DeFeo anymore. It<br />

is in a future life, and she has been born again, as<br />

someone else. She wanders through the galleries,<br />

room after room, and comes upon The Rose -<br />

unearthed, unwrapped, repaired. A person is<br />

standing in front of it, studying it intensely. DeFeo<br />

nudges this person and says, “You know, I did<br />

that.”<br />

Courtesy the Conner Family Trust (c) Conner Family Trust.<br />

REVOLT<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong> Number 4, 2013<br />

10

TOP 10 NYC<br />

!#$%12456!@#<br />

ARTISTS NOW<br />

Andrea Bonin<br />

Born 1986 in Temple, Texas<br />

Andrea Bonin makes sculptures and assemblage using plaster, wax, clay, and found material. Having grown up in a creative<br />

household (her mother a painter and father a musician), Andrea experienced working on projects and expressing herself<br />

artistically as the norm from an early age. Her work deals with domesticity and nostalgia, and is essentially about finding<br />

reverence in the everyday. Her process is very much about experimentation, gesture and material. Right now she is working<br />

on a series of drawings that mimic patterns found in wrapping paper and newspaper advertisements. She’s interested in<br />

the notion of “holiday” and has a growing collection of ornaments, tinsel and old, faded party favors. Going forward, she’s<br />

interested in bringing some expressive and performative elements into her work relating to her former years as a dancer.<br />

www.andreabonin.com<br />

Sean Paul Gallegos<br />

Born 1976 on Earth, North America<br />

For Sean Paul Gallegos being an artist is not a choice, it just is. “The beauty of being an artist at this point in time is the option<br />

to be interdisciplinary,” says an artist who 10 years ago would get schooled that he needed to focus on one medium. “Sculpture<br />

is what sells and is exciting to create, but Performance is still in my heart.” Sean currently works out of his living room. His bath<br />

tub doubles as a slop sink and his queen size bed makes for a nice cutting table or work bench at times. Currently, he’s working<br />

on “Recovering my roots and having the will to challenge what is damaging in this world.” Ultimately through his work he hopes<br />

to open eyes and hearts. He also plans to have fun working, forget about the market and create more reasons to travel.<br />

www.seanpaulgallegos.com<br />

Rebecca Goyette<br />

Born 1992 in Provincetown, Massachusetts<br />

For a long time Rebecca has been drawing, play acting, reading, and nerding out on all things related to art and sex. Her videos<br />

are a balancing act of multiple elements including sculpture, sound, image and performance. Her work relates to her “desire"<br />

to work with others and…fascination with all things tactile/sensory.” Her current body of work focuses on Lobsta Sex, using<br />

lobster mating rituals (in which female lobsters box down a mate and squirt aphrodisiac drugs out of her forehead) as a point of<br />

departure. Her greatest artistic challenge? The “thin membrane between the fantasy world I construct, inhabit and play in with<br />

others and my everyday life. Drama can erupt. Desire is complex.” Her upcoming work explores asexual love between a Blue<br />

Lobsta burlesque singer and a man who dresses in 1600’s Puritan clothing all the time shot in a seaside town in New England.<br />

www.rebogallery.com<br />

Fred Gutzeit<br />

Born 1940 in Cleveland, Ohio<br />

Fred Gutzeit’s elementary school principal told his mother that Fred should have art lessons. Years later he’s a full-fledged<br />

painter working in acrylic on canvas and watercolor on paper. Incorporating digital prints and photography into his painting is<br />

also part of his practice. Fred’s work is about finding the unexpected. Says the artist of his work, “I’d like to take your eyes for a<br />

joyride.” Since 1970, Fred has worked from his studio on the Bowery and currently his greatest challenge is pulling together the<br />

various ideas comprising the last 50 years worth of his sketchbook. He’s currently working through an idea called “SigNature,”<br />

which involves six large paintings and dozens of small watercolors and acrylic panels. He’s also planning to do an outdoor wall<br />

billboard-installation. After that he’ll continue to sort through old sketchbook ideas and work them out in permanent sculptural form.<br />

www.fredgutzeit.com<br />

Phoenix Lindsey-Hall Born 1982 in Athens, Georgia<br />

Involved from a young age with social justice and humanitarian issues, Phoenix’s work encompasses the “poetry that cannot<br />

be expressed through traditional campaign field-work or fundraising pitches.” Building her projects from research and hard<br />

numbers, her work ultimately makes a departure into “obscurity, expression and emotions.” Having worked with photography<br />

for many years, her current work is more sculptural. Themes Phoenix has engaged in her practice include queer iconography,<br />

hate crimes, war and foreclosures. Her most recent body of work, After Kempf, is an exploration of l.g.b.t hate crimes. Using<br />

mixed media - including ceramic, concrete, and found materials - Phoenix transforms everyday objects that have been used as<br />

weapons in specific hate crime cases. Phoenix is currently Artist-in-Residence at Gallery Aferro in Newark, NJ.<br />

www.phoenixlindseyhall.com<br />

REVOLT<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong> Number 4, 2013 12

Duron Jackson<br />

Born in Harlem, New York<br />

Duron Jackson has made art since a very young age and currently works in the medium of sculpture. His work is about a way of<br />

being that's widely misunderstood, and narrowly represented. His greatest artistic challenge? “Saying a lot in the most simple<br />

way.” Working out of his studio in Brooklyn, Duron showed in fours exhibitions last fall including a solo show at the Brooklyn<br />

Museum. Currently, he’s in Salvador da Bahia on a Fulbright Research Fellowship where he’s concurrently doing a residency at<br />

Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia. His plan is to “make art, eat, drink and be merry.”<br />

www.duronjackson.com/home.html<br />

Yuliya Lanina<br />

Born 1973 in Moscow, Russia<br />

When Yuliya first moved to the U.S. she planned to be a musician, but when she could not get access to musical instruments or<br />

musicians, she started drawing instead. Today she does painting, animatronic sculpture, animation and performance. Her work<br />

is about “looking at uncomfortable realities with a wink and a smile.” Having recently relocated to Austin, TX she splits her time<br />

between Austin and New York City and says “Having Internet in my studio,” is her greatest artistic challenge. After two recent<br />

solo shows in New York (Figureworks) and Cleveland (Cleveland Art Institute) she is currently working on a new animation and<br />

mechanical sculptures for her solo exhibitions at the Russian Cultural Center in Houston and W&TW in Austin . She also has a<br />

performance piece in the works.<br />

www.yuliyalanina.com<br />

Jong Oh<br />

Born 1981 in Nouadhibou, Mauritania<br />

Jong Oh is an artist working in sculpture and installation. Constantly exploring the boundaries between “something” and “nothing,”<br />

Jong’s work in a nut shell expresses “philosophical ponderings of the physical space we occupy.” He is currently looking<br />

for a wide space to make an installation of suspended wood sticks and panels. Says Jong, “I want to give the viewer a transforming<br />

spatial experience by simple compositions of lines and planes in space.” For his next series he plans to incorporate<br />

photography as a means of exploring the boundaries of interior and exterior space.<br />

www.ohjong.com<br />

Nell Painter<br />

Born 1942 in Houston, Texas<br />

Nell Painter. Photo by Bryan Thomas.<br />

Although born in Texas, Nell grew up in Oakland and considers it her hometown. After a successful career in academia, Nell<br />

turned to art and currently works in acrylic on canvas, paper, and Yupo (polypropylene paper), composing images on the<br />

computer as well as canvas. Nell’s work is about “seeing people as visual objects” and “the freedom to make visual fictions.”<br />

Nell maintains a big basement studio in the Dietze Building of the Ironbound section of Newark, New Jersey, where she is<br />

working on her current long-term project, Odalisque Atlas (about beauty, sex, and slavery). She also indulges in self-portraits<br />

and abstract drawings as purely formalist exercises. Nell recently appeared in conversation with Kara Walker at the Newark<br />

Public Library.<br />

www.nellpainter.com<br />

Tobaron Waxman<br />

Born in Toronto, Canada<br />

Benjamin Coopersmith and Tobaron<br />

Waxman, "Tashlich" (performance for<br />

photo, 2009.)<br />

Tobaron Waxman is a border crosser. Through performance, photography, video, voice and sound, he interrogates<br />

diasporic experience, contested national borders and the ways in which the State shapes gender. His work<br />

often deals with transgendered bodies, issues of consent, sexual representation, conflict and the queering of<br />

heterosexuality. Informed by his Jewish background, Tobaron’s work explores the trappings of social codes as layers<br />

and historical distortions, the authenticity of gender and embodiment as praxis. Tobaron is interested in “Place”<br />

as a dynamic tension. "The Place" being one of the names of god in Judaism, says the artist “I want the artists I’m<br />

collaborating with and the viewers to experience their citizenship of ‘The Place’ as agents of possibility.” His current<br />

work in process involves Tobaron bringing his own body back into the work as a vocalist based on a curriculum he<br />

has designed for the FTM voice derived from Western and non-Western traditions.<br />

www.tobaron.com

FASHION<br />

Today<br />

The Cult of the First Lady:<br />

The Media’s Festishistic Gaze<br />

BY EMILY KIRKPATRICK<br />

Photo courtesy of The White House.<br />

The First Lady of the United States has always<br />

been a figurehead for America, representative of<br />

the perfect wife and mother. The title of First Lady<br />

comes with no paycheck, no official responsibilities,<br />

and a life lived under almost constant media<br />

scrutiny. According to Carl Sferrazza Anthony’s<br />

REVOLT<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong> Number 4, 2013<br />

book The Role of the First Lady, “She is, first<br />

and foremost, the hostess of the White House.”<br />

Although most would, in public, vehemently<br />

disagree with that statement, the problem is<br />

that it’s still an ideological truth privately held<br />

by a majority of the population and every media<br />

outlet across America. In the past few decades,<br />

a First Lady’s position and responsibilities have<br />

evolved well beyond the realm of traditional<br />

wifely duties and fashion trendsetting. It’s<br />

now common for First Ladies to be vocal about<br />

their political opinions and pioneers on public<br />

14

initiatives aimed at fixing everyday issues faced by<br />

American citizens, ranging from the environment,<br />

to women’s rights, to illegal drugs. The American<br />

media, however, has failed to keep up with this shift<br />

in emphasis. Publications continue to focus on the<br />

superficial, banal and demeaning over the political<br />

and charitable when discussing our First Lady. The<br />

result of this discourse is a constantly backfiring<br />

attempt to limit the feminine domain and return to<br />

an era of repression, and a sexual stereotype, that<br />

no longer exists.<br />

For this reason, Michelle Obama represents<br />

a perfect storm of political and social media<br />

commentary. As a woman in the public eye, she<br />

inspires a shallow, thoughtless dialog that has<br />

surrounded the feminine sphere for far too long in<br />

this country. Due to the color of her skin, she has<br />

unwittingly unleashed this undercurrent of intense<br />

racism, hatred, and at it’s core, fear, that has been<br />

masquerading through the media under the guise<br />

of political discourse and criticism. Michelle Obama<br />

is by no means the first First Lady to receive such<br />

intense public scrutiny, especially on a physical<br />

and sartorial level. Jacqueline Kennedy Onasis<br />

continues to be remembered to this day for her<br />

contributions to fashion and style, if nothing else.<br />

But when Barack Obama was first inaugurated into<br />

office, the Michelle media frenzy hit a fever pitch<br />

which has sustained itself for the past five years and<br />

will surely remain intact well beyond the completion<br />

of his second term in office. In addition to the<br />

relatively standard trivialization of the First Lady’s<br />

appearance and activities, the comments against<br />

Michelle Obama, specifically, seem to have taken on<br />

a distinctly different tone and bitterness than they<br />

have with First Ladies of the past, such as Laura<br />

Bush or Hillary Clinton.<br />

Of course, other First Ladies have been vilified by<br />

the media and had their public lives intensely, and<br />

inappropriately, put on display. But never before has<br />

a First Lady’s allegiance to her country, the size and<br />

shape of her body, or her day-to-day decisions been<br />

so intensely analyzed and attacked as Mrs. Obama’s.<br />

The problems with the type of language the media<br />

uses when discussing any woman, but in particular<br />

Michelle, are myriad. This type of insensitive,<br />

objectifying discussion undermines the authority<br />

and respect deserving of a woman in her public and<br />

political position, as well as setting back the agenda<br />

of equality, and inviting some remarkably racist, and<br />

completely out-of-line commentary. When people in<br />

political office or on national television speak about<br />

a woman of power, such as Michelle Obama, in this<br />

type of condescending, accusatory language, it<br />

gives the rest of America permission to follow suit.<br />

The claims against Michelle Obama range from<br />

attempting to appropriate the plight of black, single<br />

motherhood into her persona, to anti-patriotism,<br />

elitist spending habits and allegiances with the<br />

Black Power Movement.<br />

As Barack Obama’s term has progressed, the articles<br />

about Michelle Obama have tended to increasingly<br />

feature style over substance. In an article for The<br />

Economist in 2009, Adrian Wooldridge wrote that<br />

most new stories about the first lady, “were almost<br />

entirely devoted to fluff.” Every fashion magazine<br />

and website in America has run at least one piece<br />

on how to attain the First Lady’s amazing wardrobe;<br />

that is if they don’t already have an entire section<br />

dedicated exclusively to her daily outfit choices.<br />

Proving Wooldrige’s point, in 2009, CNN ran a<br />

segment on “How to get Michelle Obama’s toned<br />

arms.” But, as the piece points out, not everyone is<br />

a fan of the First Lady’s muscular biceps. The article<br />

quotes Boston Herald columnist Lauren Beckham<br />

Falcone who wrote to Obama, saying, “It's February.<br />

Going sleeveless in subzero temperature is just<br />

showing off. All due respect." Clearly there was no<br />

respect intended here. Would these same journalists<br />

be ballsy enough to walk up to any shoulder-bearing<br />

stranger on the street and tell them to stop showing<br />

off and cover up? What is it about Michelle Obama’s<br />

husband’s choice in profession that makes her<br />

arms and body a permissible subject of critique on<br />

a national level?<br />

And don’t think the average American woman’s<br />

personal struggle with the First Lady’s bare arms has<br />

diminished with time! Joyce Purnick, in an article for<br />

the New York Times “Style” section in 2012, wrote,<br />

“I HAD expected to keep mum about my problem<br />

with Michelle Obama until after the election, but my<br />

frustration has gotten the better of<br />

Photo courtesy of The White House.<br />

me. I can’t contain it any longer. I refer not to her<br />

politics, but to her arms -- her bare, toned, elegant<br />

arms. Enough!” According to Purnick, the first lady<br />

has made it “unacceptable for women to appear<br />

in public with covered arms.” Because, clearly,<br />

Michelle is not only the first famous woman to ever<br />

wear sleeveless clothing, but also, a dictator of<br />

sleeve lengths for women across America. Purnick<br />

concludes her article by pointing out that Michelle<br />

will turn 49 in January, suggesting, “Could it be time<br />

for her at least to begin to ponder setting a new<br />

fashion trend? Here’s a thought. Maybe she could<br />

take a cue from her husband and, in a bipartisan<br />

gesture, adopt Ann Romney’s preference for elbowlength<br />

sleeves and red taffeta. Or not.” I think the<br />

crucial take away from that sentence is “Or not.”<br />

This quote suggests that woman of a certain age,<br />

specifically, women of a certain age and public<br />

profile, should not be able to dress as they please.<br />

They should be ashamed of their bodies and of<br />

the effect they have on American woman clearly<br />

suffering from body issues of their own. Secondly, it<br />

implies that the most politicized opinion a First Lady<br />

should have is in the realm of fashion (where she<br />

can make a “bipartisan gesture” of her own), while<br />

the heavy thinking and legislature should be left to<br />

her wiser, more powerful husband.<br />

Lucky for all the tabloids, as the buff arms stories<br />

began to grow stale, Obama was inaugurated into<br />

office for his second term, and the First Lady had<br />

some exciting new changes of her own planned.<br />

According to Joselyn Noveck, a writer for the AP,<br />

“the president started it.” She’s referring, of course,<br />

to the media’s new, unbridled obsession with<br />

Michelle Obama’s bangs. According to Noveck,<br />

media outlets around the world are completely<br />

justified in talking exclusively about a First Lady’s<br />

haircut because of a husband’s admiration for his<br />

wife. Obama’s comment was clearly intended as a<br />

joke, considering he referred to the bangs as "the<br />

most significant event of this [inaugural] weekend."<br />

Despite the transparent flippancy of his statement,<br />

this quote was repeatedly taken out of context and<br />

used to justify a whirlwind of bang commentary and<br />

speculation. The Bangs even spawned their own<br />

Twitter account, which sends out thought-provoking<br />

tweets such as, "Just got a text from Hillary Clinton's<br />

side-part.” In a 2012 piece for The Washington Post,<br />

Rahiel Tesfamariam wrote, “Since the beginning of<br />

the president's term, there's been an ever-present<br />

demand to "publicly dissect" [Michelle Obama] and<br />

examine why she dresses the way she dresses, says<br />

what she says, and behaves the way she does.” The<br />

public is not satisfied until each of her decisions has<br />

been broken down and analyzed in order to suss out<br />

and reveal her presumed secret motivations behind<br />

every act. Even down to something as simple as a<br />

choice in hairstyle is suspected to have nefarious or<br />

manipulative motives.<br />

On December 28, 2012 in an article by Cathy Horyn<br />

for The New York Times, Valerie Steele, the director<br />

and chief curator of the Museum at FIT, commented,<br />

“Oddly, fashion, which has tended to be treated<br />

with extreme suspicion in American history, has<br />

not caused political problems for her.” It seems to<br />

me that this is the case because if we can trap a<br />

powerful woman in this shallow discourse, we lessen<br />

the appearance, and thus the threat, of power and<br />

authority in her decision making. By taking the focus<br />

away from her education, her intelligence and her<br />

position of authority, and reducing it to simply what<br />

she wears every day, how muscular her arms are,<br />

and how she styles her hair, she becomes “safe.” If<br />

we reduce her to a 1950s conception of what women<br />

should be and what their pursuits should entail, she<br />

can be viewed as posing no political or intellectual<br />

threat to the overwhelmingly white male patriarchal<br />

government. And the patriarchy is most certainly<br />

intimidated by Michelle Obama, as media and<br />

political pundits prove daily with their increasingly

absurd and misogynistic claims leveled against her.<br />

But men are not the only culprits of perpetuating<br />

this type of discourse, Horyn goes on to quote a<br />

designer who, “observed, with some accuracy, ‘Her<br />

clothes are too tight.’” As though this criticism is<br />

not only of the utmost importance, but also a strike<br />

against her and an indictment of her character.<br />

Even though America has pushed Michelle Obama<br />

to embrace her role as its First Lady fashionista,<br />

she is not even permitted to find respite within this<br />

feminine stereotype. When she plays into the heavily<br />

gendered role she’s been dealt, the criticism is just<br />

as intense and focused as when she was viewed as<br />

her husband’s radical-thinking co-conspirator.<br />

The New Yorker on January 22, 2013 justified<br />

the lack of negative media attention surrounding<br />

Michelle Obama’s pricey clothing (which, in fact,<br />

there has been a substantial amount of critique on),<br />

by saying, “When her husband ran for President in<br />

2008, there were barely veiled insinuations about<br />

whether the role of First Lady was really right for<br />

her—whether she was too angry, or could really<br />

Photo courtesy of The White House.<br />

feel comfortable. (One suspects that a sense of the<br />

pressures on her may explain why she is not taken to<br />

task as much as she might be for the price of these<br />

clothes.)” So, in other words, in the face of massive<br />

amounts of criticism surrounding her aptitude to<br />

simply be married to the President of the United<br />

States, her luxurious fashion expenditures have<br />

been forgiven as an effort to fit in. Horyn’s 2012<br />

New York Times article suggested a very similar<br />

idea, saying, “It’s a funny thing: four years ago she<br />

denied conservatives the chance to vilify her as ‘an<br />

angry black woman’ by taking immense pleasure<br />

in traditional first lady pursuits, like fashion,<br />

entertaining and gardening.” In other words, the only<br />

safe place in politics for intelligent women to prove<br />

themselves as true role models and not be branded<br />

as angry, bitchy, or stubborn shrews, is to retreat<br />

into the shallow, vain realm of the traditionally<br />

feminine. These articles promote the idea that if a<br />

woman is opinionated, politicized or powerful she<br />

automatically, and unquestionably, is asking for<br />

criticism. Traits that are respected and encouraged<br />

in male political candidates, in women, become<br />

egregious trademarks of an overbearing personality<br />

that has overstepped its proper bounds and can only<br />

be tamed by relegating her authority and decision<br />

making into venal pursuits. Even the topics the First<br />

Lady endorses during her husband’s presidency<br />

are meant to be of the simplest, most ethically<br />

uncontroversial nature (although, there are a handful<br />

of First Ladies who have proved exceptions to this<br />

rule). Laura Bush, for example, promoted education,<br />

while Michelle promotes “Let’s Move,” a campaign<br />

devoted to ending childhood obesity in America and<br />

promoting healthy eating habits. However, even this<br />

meager, unquestionably positive health initiative<br />

(a step towards the demure femininity expected of<br />

Mrs. Obama), has not managed to escape the wrath<br />

of politicians and pundits claiming Mrs. Obama is<br />

trying to tell Americans how to raise and what to<br />

feed their children.<br />

Wisconsin Republican congressman Jim<br />

Sensenbrenner very publicly took the First Lady’s<br />

health initiative to task, when he was overheard<br />

at Washington’s Reagan National Airport loudly<br />

criticizing “Let’s Move,” saying, “She lectures us<br />

on eating right while she has a large posterior<br />

herself.” After causing a media sensation with<br />

his rude, insensitive, and plainly inappropriate<br />

remarks, Sensenbrenner (who is not exactly the<br />

paragon of health himself) promised to “send the<br />

first lady an apology.” It’s clear from his statement<br />

that Sensenbrenner’s problems lie not with the<br />

First Lady’s initiatives to promote healthy children,<br />

but rather with her body. This is a fundamentally<br />

misogynist issue many male Republicans seem<br />

to currently be struggling with: the belief that it is<br />

their right to objectify, comment upon and legislate<br />

the female body. The lack of backlash and public<br />

outrage against Sensenbrenner only encourages<br />

such invectives and makes it seem acceptable, even<br />

permissible, to discuss a First Lady’s posterior when<br />

describing her politics. Criticisms that were once<br />

considered taboo, particularly when discussing the<br />

first family, have suddenly been given a no-holds-bar<br />

policy under the Obama administration. It seems<br />

that white politicians and the media have made<br />

the collective decision that electing a black man<br />

into office has lifted a moratorium on the political<br />

incorrectness of full-blown, uncensored racism and<br />

sexism.<br />

Much like Sensenbrenner, in January 2012, a<br />

speaker of the Kansas House, Republican Mike<br />

O’Neal, had to apologize after forwarding an email<br />

around the House which referred to the First Lady<br />

as “Mrs. YoMama.” He claims that he forwarded<br />

the email on without reading it, simply enjoying the<br />

picture of Mrs. Obama side by side with the Grinch<br />

above the caption “Twins separated at birth?” In his<br />

mind, this seemed to excuse the racist slur found<br />

above. In a public statement, O’Neal said that he<br />

found the cartoon amusing because, “I’ve had bad<br />

hair days too.” An unacceptable response to even<br />

more unacceptable behavior. But it’s not just her<br />

physical appearance that has riled a conservative<br />

nation, but also the ease with which she’s accepted,<br />

even embraced, her role as a pop icon and a woman<br />

who wields substantial media power.<br />

The American media has turned Michelle Obama<br />

into a celebrity, a pop culture phenomenon and an<br />

arbiter of style. Yet, at every turn, as she accepts<br />

and utilizes her unique status and position to<br />

promote positive change, she is greeted with<br />

immense backlash, criticizing her for feeding into<br />

the Hollywood machine. When she was invited to<br />

pose for the cover of Vogue in 2008, her advisers<br />

were concerned that she might be seen as “a<br />

fashionista,” a status she assuredly already had<br />

and that has only grown throughout the duration of<br />

her husband’s presidency. To Michelle’s credit, she<br />

made the compelling argument in favor of posing<br />

for the cover, saying that, “there are young black<br />

women across this country, and I want them to see a<br />

black woman on the cover of Vogue.” In the end, the<br />

cover received little notoriety or criticism, unlike her<br />

2013 Oscar appearance where she announced, via<br />

satellite along with Jack Nicholson, the Oscar winner<br />

for Best Picture. The Washington Post claimed that<br />

“attendees and viewers were flabbergasted at the<br />

satellite image of the elegantly dressed, Obama.”<br />

Many accused her of indulging in the frivolities of<br />

stardom and the media criticized her for playing<br />

the role of the Hollywood starlet. An ironic jab at<br />

Michelle, considering these publications are a part<br />

of the same publicity machine that simultaneously<br />

encourage this exact type of celebrity tabloid<br />

coverage surrounding the First Lady, cataloging her<br />

outfits and purchases down to the smallest detail.<br />

The American people and media have cast Michelle<br />

Obama in the role of entertainer and then condemn<br />

her when she chooses to play along.<br />

America has created a no-win situation for the First<br />

Lady. Either she’s a political and intellectual radical<br />

and “angry black woman,” or she is a fashionista<br />

with a spending problem and an over-investment in<br />

frivolous, undignified pursuits. In the 2009 Economist<br />

piece by Wooldridge, he said, “I think if a first lady<br />

were purely decorative in the 21st century, it would<br />

actually look rather odd.” But isn’t that precisely the<br />

position the media is attempting to cast Michelle<br />

Obama in? The media, Obama’s fellow politicians,<br />

even the White House itself has attempted to paint<br />

her as this decorative, fashionable mouthpiece of<br />

“change.” Michelle, much like Hilary before her,<br />

is not the quiet, demure woman behind the man<br />

that is easily silenced or brushed aside. Both are<br />

smart, capable progressive women who seek to use<br />

their political positions as platforms to make real<br />

progress forward. When we limit our discussion of<br />

women in power to their physical appearance and<br />

choice in apparel and hairstyle, we strip them of<br />

their authority and try to re-appropriate them as flat,<br />

antiquated images of womanhood. We are in the<br />

midst of a struggle to redefine the spheres females<br />

are allowed to encompass and wield authority<br />

within, and news sources, by proliferating these<br />

REVOLT<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong> Number 4, 2013 16

conservative blogger went so far as to suggest<br />

that even if Michelle didn’t vocalize her unpatriotic<br />

sentiments, we all know she was thinking it. In a<br />

post on her right-wing, consistently inflammatory<br />

blog, Schlussel wrote: “The consensus seems to be<br />

that the First Ms. Thang is saying to hubby Barack,<br />

"All of this for a damn flag." (She said this about the<br />

Photo courtesy of The New Yorker.<br />

Photo courtesy of The White House.<br />

stereotypes, are thwarting those efforts at every<br />

turn. Further proving this point, Wooldrige highlights<br />

that the White House is “doing its best to turn<br />

the first lady into a celebrity mother-cum-clotheshorse,”<br />

emphasizing her primary role as mother and<br />

daughter above all else. According to Wooldrige, this<br />

is because, “Hilary Clinton’s determination to act as<br />

a virtual co-president back in 1993 helped to create<br />

a backlash against her husband’s administration. It<br />

also raised uncomfortable questions about power<br />

and accountability. Given America’s continued<br />

neuroses about race, an outspoken black first lady<br />

might have proved to be even more divisive than an<br />

outspoken white one.”<br />

It’s easier to sweep Michelle Obama’s identity as an<br />

intelligent, informed, politicized black female under<br />

the rug, rather than confront head-on these issues of<br />

extreme racism and sexism. In fact, the White House<br />

itself is encouraging this trivialization of her position<br />

and the backwards media stereotypes surrounding<br />

a woman’s proper role in the home. How is the rest<br />

of America meant to be respectful of the First Lady<br />

and honor her intellectual and political successes<br />

when our own government can’t see beyond her role<br />

as child and a child-bearer? The list of complaints<br />

and grievances Michelle Obama has been charged<br />

with, at this point, seems completely exhaustive and<br />

all-encompassing, fully cataloguing every physical<br />

and intellectual perceived transgression. However,<br />

the media, unsatisfied with their endless complaints<br />

thus far, has now moved well beyond the realm of<br />

facts, extending their grievances to include both her<br />

fictionalized beliefs and assumed, although unseen,<br />

behaviors.<br />

Usually news stories cease to exist when the subjects<br />

stop providing material. However, The Washington<br />

Post in a piece from September 13, 2011 proved<br />

that nothing could stop them, when they dispensed<br />

with all attempts at real journalism and based an<br />

entire article around their attempt to read Michelle<br />

Obama’s lips during a ceremony in honor of the<br />

victims of 9/11. The article stated that as police and<br />

firefighters folded the flag, “a skeptical looking Mrs.<br />

Obama leans to her husband and appears to say,<br />

‘all this just for a flag.’ She then purses her lips and<br />

shakes her head slightly as Mr. Obama nods.” This<br />

libelous and fictional account suggests that both<br />

America’s President and First Lady are complicit in<br />

both their disregard for one of our greatest national<br />

tragedies and an iconic American symbol. Typically<br />

in media attacks against a public or political figure,<br />

it’s an unspoken rule, for both litigious and credibility<br />

reasons, that publications stick to recorded audio<br />

of public gaffes. However, in a desperate attempt to<br />

discredit and shame the President and First Lady,<br />

no traditional journalistic rules or integrity seem to<br />

apply any longer. Under the Obama administration,<br />

an insinuated attack, based off an audioless clip<br />

and the accusations of random, unaccredited<br />

bloggers is foundation enough for the media to<br />

run wild with anti-American accusations. Debbie<br />

Schlussel, a radio host, political commentator and<br />

American flag -- you know the one brave men died<br />

for.) Wouldn't be surprised if that's what she said<br />

because we know she hates America and previously<br />

said she wasn't proud of our country until Obama<br />

had a chance to become Prez. Looks like that's what<br />

she said, but I can't tell for sure. I would need a deaf<br />

person or other expert lip reader to confirm. Watch<br />

and see if you agree (like I said, even if she didn't<br />

say exactly that, we know she's thinkin' it).”<br />

This isn’t even the first time it’s been suggested<br />

that Michelle, much like her husband, is thoroughly<br />

unpatriotic and un-American. During a number of his<br />

shows in February 2008, Sean Hannity repeatedly<br />

distorted passages from Michelle’s 1985 Princeton<br />

senior thesis, in which she discussed the effect of<br />

Photo courtesy of The New Yorker.

the Black Power Movement on the attitudes of black<br />

Princeton students during the 70s. Hannity claimed<br />

that she herself held, “the belief that blacks must<br />

join in solidarity to combat a white oppressor.”<br />

Failing to note that the First Lady’s thesis goes on<br />

to say, “One can contrast the mood of the campus<br />

years ago and the level of attachment to Blacks to<br />

that of the present mood on the campus [in 1985]<br />

which is more pro-integrationist.” Hannity posed<br />

a rhetorical question on his program, saying, “She<br />

talked about why African-Americans joined together<br />

at Princeton. Is race going to now be an issue for<br />

them?" The irony of Hannity’s statement is that he<br />

fails to see that it is precisely this type of discourse,<br />

which programs such as his proliferate, that makes<br />

race a serious issue for this presidency every single<br />

day. Not because the Obamas are attempting to<br />

push some radical Black Panther agenda, but<br />

because they are never permitted to forget about<br />

the color of their skin. Much of the right-wing<br />

media’s criticism focuses around the issues of race;<br />

whether they believe the Obama’s to be pandering<br />

to minorities, plotting some sort of black American<br />

revolution, accusing Obama of manipulating the<br />

public with his “coolness” (read: blackness), or<br />

accusing him of lying about his Kenyan origins.<br />

Hannity couldn’t even muster support for his<br />

conspiracy theories amongst his guests, including<br />

Tennessee Republican Congressman Harold Ford<br />

Jr. who replied to Hannity’s line of anti-patriotic<br />

questioning by saying, “If we're looking back to how<br />

spouses of presidential candidates, when they were<br />

students in elementary and junior high and middle<br />

and high school and even college, to determine<br />

whether or not their husband or their spouse<br />

is fit to be president, I think we've sunk to a new<br />

low. Michelle Obama is a model for what anybody<br />

would want their daughter to be. She's smart. Not<br />

only a -- wonderfully capable and accomplished<br />

academically, but she's an incredible mom.”<br />

But, clearly, Michelle Obama was not always viewed<br />

as an ideal role model and mother, certainly by<br />

some of her husband’s right-wing constituents, but,<br />

also, surprisingly, by some left-leaning publications.<br />

During his first presidential campaign, The New<br />

Yorker published a cartoon on their cover portraying<br />

Mrs. Obama with an afro and machine gun giving<br />

Barack a “terrorist fist jab,” implying the radical,<br />

revolutionary Obamas had infiltrated the White<br />

House. However, The New Yorker cover for the<br />

March 16, 2009 issue, a mere year later, shows how<br />

quickly Michelle’s public persona was manipulated<br />

and transformed by the media and spun by the<br />

White House. The 2009 cover shows her walking<br />

the runway in three different stylish outfits. This is<br />

the perfect illustrative example of both the media’s<br />

attempt to mollify or domesticate the image of the<br />

First Lady and the larger dichotomy at hand, which<br />

women in politics must face every day. Either she is<br />

her husband’s co-conspirator, plotting some grand,<br />

black radical takeover of America, or she is the<br />

consummate fashion plate who can’t be bothered<br />

with America’s poor and disenfranchised. As a<br />

woman in the American political limelight, you’re<br />

afforded two possible identities, either that of an<br />

intelligent, shrewd harpie or a vain, thoughtless<br />

socialite. Women’s identities can be condensed<br />

down to these rudimentary understandings, unlike<br />

their male counterparts who are permitted to be as<br />

complex, diverse, and often contradictory as they<br />

like.<br />

Michelle Obama doesn’t fit America’s racial<br />

stereotype of what a black woman should be, so<br />

she’s degraded and insulted and marginalized by<br />

the media until they can find a way to make her fit<br />

into their preconceived notions. We’ve created a<br />

culture surrounding the White House where it’s not<br />

only permissible to say any passing racist or sexist<br />

remark that comes to mind, but it’s all right to gossipmonger,<br />

speculate and fabricate whatever story or<br />

quote is needed in order to support the argument<br />

against a black President and First Lady who were<br />