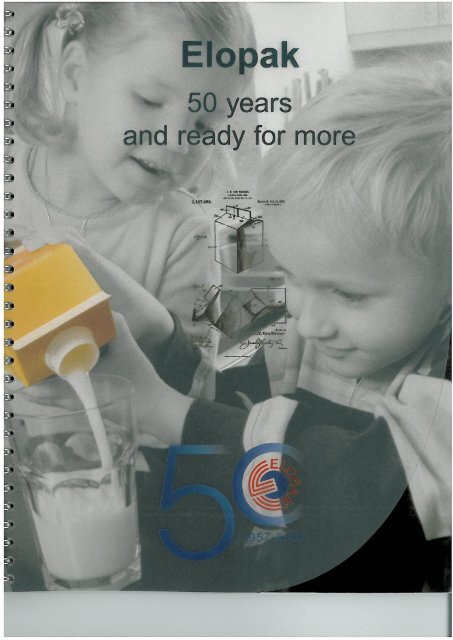

50 Year Anniversary Book - Elopak

50 Year Anniversary Book - Elopak

50 Year Anniversary Book - Elopak

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s Vision<br />

We will contribute to human<br />

health and lifestyle<br />

– effectively and responsibly –<br />

by becoming the leading international player in<br />

fresh and premium aseptic<br />

liquid food packaging.<br />

Contents<br />

Part of the big picture 5-7<br />

The advent of the “paper bottle” 9-11<br />

A vision becomes reality 13-15<br />

A global company takes shape 17-19<br />

Research for the breakfast table 21-23<br />

A focus on environmental responsibility 25<br />

The way ahead 27-28

Fifty <strong>Year</strong>s of Enthusiasm<br />

Owning <strong>Elopak</strong> has at times been a challenging and even nerve-wracking<br />

experience – but it has always been inspiring. Admittedly, during the initial<br />

stages, there was reason to doubt the viability of the venture. But for<br />

Christian August Johansen – the man who turned up at JL Tiedemanns<br />

Tobaksfabrik with a daring vision and a Pure-Pak license – capital and<br />

business know-how were absolutely essential. One of those who saw the<br />

potential in this business idea, and found ways to finance it, was Edgar J.<br />

Johannesen, a senior member of personnel within the Tiedemanns group,<br />

and a key player during <strong>Elopak</strong>’s establishment.<br />

Fifty years down the line, it’s good to be able to say that the pioneers had<br />

the right idea. <strong>Elopak</strong> has grown from humble roots as a little beverage<br />

carton factory in Spikkestad into a truly global company. Recent years<br />

have seen further progress and <strong>Elopak</strong> has made its mark with attractive<br />

innovations in a sector characterised by tough competition from much<br />

larger players.<br />

In this anniversary year, <strong>Elopak</strong> is in a position to strive for further growth,<br />

secure in the knowledge that in Ferd they have an owner that is both<br />

demanding and dynamic. All <strong>Elopak</strong> employees should look on this as a<br />

vote of confidence!<br />

Johan H. Andresen (Senior)<br />

Johan H. Andresen (Junior)

Part of the big picture...<br />

A demanding, research-based product. Resource-saving<br />

and highly CO2-efficient, important for ensuring food<br />

safety, user-friendly, and with sales in the billions. And<br />

manufactured by one of Norway’s most international<br />

companies, a company which has acquired its own<br />

American “mother”... Behind <strong>Elopak</strong> and the Pure-Pak<br />

carton lies a truly fascinating story.<br />

For the 2200 people around the world who work for <strong>Elopak</strong>,<br />

it is nothing new that the beverage carton on the breakfast<br />

table is a piece of advanced technology. Nor that it is the<br />

result of science, ingenuity, commitment and hard work at<br />

every stage of the process – from concept to the finished<br />

packaged product lining shop shelves or refrigerated<br />

cabinets. A product to be proud of. One has just come to<br />

accept the fact that most consumers regard the carton as<br />

a piece of colourfully printed, folded cardboard...<br />

In all probability, those same 2200 people also feel a<br />

stab of pride when they experience a Pure-Pak machine<br />

the size of a locomotive in action, an entire little factory<br />

that automatically and rapidly sends millions – billions –<br />

of packages through the many complicated processes<br />

needed to provide demanding consumers with the perfect<br />

product for their breakfast tables. Error margins are close<br />

to zero and there is little tolerance for downtime.<br />

One talked about “the wonders of technology” in<br />

earlier days. Today, most people take them for granted<br />

without thinking about what goes on behind the scenes.<br />

Even among <strong>Elopak</strong>’s own employees there are probably<br />

only very few that know much about the hundred years of<br />

development and the extensive research work behind it.<br />

In this booklet, we devote some attention to the beverage<br />

carton as a phenomenon – in the past, present and future<br />

– and at the same time, think a little about the people and<br />

the industry behind the product we have all come to know<br />

so well. The occasion is the <strong>50</strong>-year anniversary of the<br />

establishment of <strong>Elopak</strong>. A rare alliance of foresight and<br />

a willingness to go all-out and take risks gave Norway a<br />

Pure-Pak licensee with ambitions that far surpassed<br />

supplying milk to the local community. That the name<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> is itself an abbreviation of European Licensee of<br />

Pure-Pak really says it all.<br />

These same properties, supplemented by staying<br />

power and financial far-sightedness – and not least, the<br />

concerted efforts of thousands of employees in many<br />

countries – have, over the course of the last fifty years,<br />

transformed <strong>Elopak</strong> into a major, global company. Today,<br />

94 percent of turnover originates from outside national<br />

borders. <strong>Elopak</strong> is undoubtedly one of the most<br />

international businesses in Norwegian industry, following<br />

Looking after resources: Norwegian children learn at school<br />

how to rinse, fold and pack together the cartons, which are then<br />

sent to be recycled.<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 5<br />

its 1987 take-over of the American Ex-Cell-O group’s<br />

packaging division, and therein all rights to the Pure-Pak<br />

system worldwide.<br />

It’s not every day that a licensee from a small country<br />

like Norway takes over as central licensor for a global<br />

product. For the majority of Norwegians nonetheless,<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> is a well kept secret even if they come into contact<br />

with Pure-Pak cartons on a daily basis. This is due partly<br />

to the fact that the company enjoys a low media profile,<br />

but it is also because a well run company with effective<br />

products does not attract dramatic headlines.<br />

The beverage carton and the world’s resources<br />

On the rare occasions when packaging does attract the<br />

media – more often than not, it is from such perspectives<br />

as wasting natural resources, the affluent society, environmental<br />

pollution, waste mountains...<br />

In reality, packaging in general and beverage product<br />

packaging in particular, are remarkably resource-saving<br />

phenomena. Studies have been conducted which prove<br />

that almost <strong>50</strong> percent of all liquid food products made in<br />

the developing world spoils before it gets to the table, while<br />

a proportion of the remaining <strong>50</strong> percent loses and<br />

nutritional value. A main cause of this is lack of<br />

appropriate packaging.

6 •<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE<br />

Global under-consumption of food product packaging<br />

has moreover a huge negative impact on total CO2 emissions.<br />

When you know that on average 90 percent of the<br />

energy consumption that goes into manufacturing a litre<br />

of milk relates to the milk itself and ten percent to the<br />

packaging, then you don’t have to be a mathematician to<br />

work out that even a small increase in the use of protective<br />

packaging can produce huge environmental benefits.<br />

In other words, the problem is not that too much<br />

packaging is being used worldwide, but that too little is<br />

being used!<br />

However, packaging is not one thing. Some types are<br />

significantly more environmentally-friendly than others;<br />

some are indispensable to a modern society, others we<br />

could do without.<br />

For the people who work for <strong>Elopak</strong>, or the consumers<br />

who come into daily contact with <strong>Elopak</strong> products, it could<br />

be nice to know that Pure-Pak scores highly on both<br />

environmental sustainability and usefulness. The principal<br />

raw material in Pure-Pak cartons is cellulose, made from<br />

trees harvested from forests in the northern hemisphere,<br />

from areas where forests are growing. In other words,<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s products are based on renewable resources.<br />

They do not contribute to deforestation or cutting down<br />

the rain forest, but on the contrary to maintaining<br />

sustainable forestry in countries such as Finland,<br />

Sweden, Norway, Canada and the USA.<br />

Additionally, the fibres can be recycled and used to<br />

make new paper; where this is not feasible, the cartons<br />

can be burned to recover energy. Of course, the carton<br />

has a thin plastic or aluminium layer and perhaps a<br />

plastic screw top, but these too can be recycled or burned<br />

without producing toxic waste.<br />

For decades, the competition between the different<br />

types of beverage product packaging has been tough.<br />

Glass, plastic, metal cans and beverage cartons battle<br />

over areas of application and market shares – competition<br />

between plastic and cartons has been particularly<br />

hard in the dairy sector. The repercussions vary greatly<br />

from one country to another. For example, milk in plastic<br />

bottles is a rare phenomenon in the Nordic countries; in<br />

Britain it is the norm. And in many countries, the distribution<br />

between packaging types changes over time –<br />

dependent to some extent on the preferences and habits<br />

of the consumer, but also often the result of lobby<br />

groups, retail-chain interests and the marketing efforts of<br />

packaging manufacturers.<br />

However, an increasingly more widespread<br />

acknowledgement that the world’s CO2 emissions must<br />

be cut provides every reason to believe that the beverage<br />

carton will gain new ground in the years to come. Glass<br />

bottles are heavy and energy-intensive to transport and<br />

recycle; plastic packaging, when burned, contributes to<br />

CO2 emissions – while the beverage carton is easy<br />

to transport and close to CO2 neutral when it is<br />

appropriately recycled after use.<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> Facts and Figures<br />

Turnover (2006): NOK Five billion<br />

Number of employees: 2200<br />

Share of turnover outside Norway: 94 %<br />

Sold in over 100 countries<br />

Production Plants: The Netherlands, Germany, Finland,<br />

Denmark, Serbia, Ukraine, Canada, with joint ventures in<br />

Mexico and Saudi Arabia (blanks and/or coating);<br />

USA (filling machines); Finland (materials handling<br />

equipment), joint ventures in Israel and Luxembourg (screw<br />

cap production) and Greece (plastic bottles)<br />

Offices: Baltic States, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France,<br />

Greece, Ireland, Israel, Italy, China, Croatia, Malaysia, The<br />

Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Spain, United<br />

Kingdom, Switzerland, Sweden, The Czech Republic,<br />

Germany, USA, Ukraine, Hungary, Austria<br />

Joint ventures: Lala <strong>Elopak</strong> S.A de C.V. (49 %), Mexico and<br />

other Latin-American countries; Elocap Ltd (<strong>50</strong>%), Israel and<br />

Luxembourg; <strong>Elopak</strong> Plastic Systems Hellas SA (<strong>50</strong>%),<br />

Greece; Al-Obeikan <strong>Elopak</strong> Factory for Packaging Co. (49%),<br />

Saudi-Arabia; <strong>Elopak</strong> South Africa Ltd (<strong>50</strong>%).<br />

Partners and Associates: Shikoku-Kakoki Co (filling<br />

machines), Japan; Nippon Paper-Pak, Japan; VisyPak<br />

Beverage Packaging, Australia; Offsetec, Ecuador; Hankuk<br />

Package Co, Korea; Taiwan Benefit Co, Taiwan

<strong>Elopak</strong> and the others<br />

Over the course of the beverage carton’s hundred-yearlong<br />

history - the subject of the following chapter – there<br />

have been countless large and small manufacturers<br />

worldwide. The majority are long gone or have been<br />

taken over by other, larger players. <strong>Elopak</strong> too has<br />

engaged in its share of take-overs down through the<br />

years. The industry has experienced continuous change;<br />

the last major restructuring took place as recently as the<br />

end of 2006. The industrial and financial group Ferd,<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s owner, joined forces with London-based global<br />

private equity group, CVC Capital Partners, to acquire the<br />

Swiss beverage carton manufacturer SIG. The idea was<br />

to merge <strong>Elopak</strong> and SIG, two companies who complemented<br />

each other well on a product level. Together the<br />

companies would form the world’s second largest player<br />

in a market, which today is dominated by Swedish Tetra<br />

Pak.<br />

But it didn’t quite work out that way. New Zealand’s<br />

Rank Group put forward a competitive bid that Ferd and<br />

CVC found they could not justifiably exceed. Rank therefore<br />

became the second largest player, while <strong>Elopak</strong> took<br />

up position as the smallest of the big three, who together<br />

comprise the vast majority of the global beverage carton<br />

sector.<br />

Consequently, <strong>Elopak</strong> is now fully focused on autonomous<br />

development, building on and strengthening its<br />

success over the last fifty years. We discuss this in<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 7<br />

greater detail in the booklet’s final chapter; suffice it to<br />

say for now that after the turn of the millennium, <strong>Elopak</strong><br />

established itself as the most innovative of the players<br />

within the beverage carton sector. At the same time,<br />

innovation work has been firmly rooted in an awareness<br />

of the customer’s needs and wishes. This is essential for<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>. Its position as the smallest of the three major<br />

players entails that it is unrealistic to base its competitive<br />

position on high volumes and low prices. Therefore<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> has chosen to cultivate activities within the<br />

premium segments for fresh and aseptic packaged<br />

products. In order to succeed at this, it is essential to be<br />

able to offer attractive features and added value in<br />

relation to less expensive solutions.<br />

And this position is in the spirit of true Pure-Pak<br />

tradition. There is a sense of continuity in that the original<br />

gabled carton gained ground on the basis of consumers<br />

who wanted Pure-Pak’s user-friendliness, although some<br />

dairies showed a preference for competing products that<br />

were slightly less expensive.<br />

Right enough, when the original patent expired, other<br />

manufacturers imitated Pure-Pak in detail. And in the<br />

past, neither Ex-Cell-O nor <strong>Elopak</strong> were overly concerned<br />

with innovation as means of maintaining Pure-Pak’s position<br />

which consequently suffered for a period. But this is<br />

all ancient history – today, the Norwegian-based company<br />

is an aggressive contender in a global market.<br />

The Big Three<br />

On a global level, today’s beverage carton sector is<br />

dominated by three major players:<br />

Tetra Pak: Originally Swedish. Now with<br />

headquarters in Switzerland, in a league of its<br />

own, the biggest player with a global market<br />

share of around 70 percent and activities in<br />

most markets.<br />

Rank Group: New Zealand. Owns SIG<br />

in Europe, Blue Ridge and International<br />

Papers in the USA.<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>: Norway. Markets and<br />

licenses the Pure-Pak system<br />

worldwide. The third-largest<br />

player and market leader<br />

within fresh products.

8 •<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> ÅR OG KLAR FOR MER

The advent of the “paper bottle”<br />

The hundred-year-long history of the beverage carton<br />

reveals a great deal about the complicated nature of the<br />

product and manufacturing equipment: more than 20 years<br />

passed before someone managed to produce a<br />

conveniently usable milk carton – and just as long again<br />

from the invention of Pure-Pak until one of the USA’s<br />

leading manufacturers of precision machines mastered<br />

the Pure-Pak system.<br />

Light, practical packaging – protects the fantastic properties<br />

of the milk or juice, but is discarded after use...<br />

This was the stuff of dreams in a world where the<br />

woman in the milk shop bailed a litre or two into a specially<br />

brought along for the purpose hopefully well-cleaned milk<br />

bucket, or where the milk came in heavy glass bottles –<br />

which, when empty, had to be thoroughly rinsed and<br />

brushed with a bottle-brush before being sent back to the<br />

shop, the milkman, the dairy. A dirty job, especially if you<br />

left it until the milk dregs had dried in, not to mention if the<br />

bottle had contained a fermented milk...<br />

No, it is no coincidence that consumer demand has<br />

been pivotal in many of the markets to which user-friendly,<br />

disposable packaging has been introduced, more often than<br />

not in the face of fierce opposition from authorities and<br />

dairies who had invested heavily in other types of systems.<br />

Bright ideas<br />

The first known description of the sale of milk in paperbased<br />

packaging originates from the USA. In a book from<br />

1908, a Dr. Winslow in Seattle, Washington, describes a<br />

disposable, paper-based milk container invented by G. W.<br />

Maxwell in San Francisco. According to Winslow, the<br />

carton was used in Los Angeles as early as 1906 – but<br />

without success. It was purported to be rather impractical<br />

and quickly and quietly disappeared.<br />

In the years that followed, there were experiments with<br />

waxed bags as well as metal cans but it was first and foremost<br />

paper-based containers that aroused the most<br />

interest. In the 1920’s, there were apparently ten manufacturers<br />

offering carton-based packaging for milk in the<br />

USA. But all ten supplied pre-folded and pre-glued cartons<br />

that were ready for filling. This meant that all transportation<br />

and storage would also have to entail the transportation<br />

and storage of large amounts of air.<br />

Then the toy manufacturer John Van Wormer in Toledo,<br />

Ohio, had a better idea: as early as 1915, he had patented<br />

a carton made of waxed paper that could be delivered to<br />

the dairy in folded format, glued along the sides but not at<br />

the ends. Now he was working on constructing the<br />

machines that would be needed to form, fill and seal the<br />

new carton, to which he had given the name Pure-Pak.<br />

The idea was stunningly simple, but its implementation<br />

turned out to be anything but straightforward. Van Wormer<br />

took ten years to complete his first machine. It worked to<br />

some extent but not well enough to achieve commercial<br />

success, and the inventor realised that he would not be<br />

able to complete the project on his own. In 1928, he sold<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 9<br />

both the patenting rights and the brand name to the<br />

American Paper Bottle Company, who would further<br />

develop the technology. The company built six new<br />

machines in the period between 1929 and 1934, but were<br />

unable to make them work properly.<br />

At the same time, several competitors were working<br />

on producing “paper bottles”, and in 1929 the press<br />

reported that two big dairies in New York had begun to use<br />

Sealcone brand conical milk cartons. In other words, pressure<br />

was building to get the Pure-Pak machines up and<br />

running. Towards the end of 1934, the American Paper<br />

Bottle Company therefore decided to ask Ex-Cell-O, one of<br />

the USA’s most well-known manufacturers of precision<br />

equipment, to take over the work.<br />

Technically excellent, surrounded by enemies<br />

Ex-Cell-O Corporation in Detroit was started by ex-Ford<br />

employees in 1919, and was in 1934 best known as a<br />

supplier of precision machinery for car manufacturing and<br />

airplane parts. However, the company also supplied<br />

precision machinery and parts to around thirty other<br />

sectors – so one could easily use one’s machinery-related<br />

skills to supply the dairies too…<br />

A timeless concept: Today’s Pure-Pak is easily recognisable in<br />

John Van Wormer’s patent application from 1915.

10 •<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE<br />

It would prove to be the most challenging assignment in<br />

the company’s history. The problems began when the<br />

American Paper Bottle company ran out of money after a<br />

short time. Ex-Cell-O took over the rights to the brand<br />

name, packaging and machines – only to discover that the<br />

filling units that were already installed, and for which<br />

Ex-Cell-O had taken over the guarantee liability, did not<br />

work at all as expected and had to be replaced with new<br />

equipment.<br />

It was even worse to discover that the company had<br />

moved into a sector where most of the players were hostile<br />

to the newcomer. Among the opponents were, as one<br />

might imagine, bottle manufacturers, transport companies<br />

that transported heavy glass packaging back and forth,<br />

suppliers of crates, bottle caps, filling equipment and bottle<br />

washing machines. But also many of the dairies, who<br />

should have formed the customer base, proved to be<br />

extremely negative. They had invested large sums in<br />

bottles and related manufacturing equipment and had little<br />

desire to spend money on new and expensive Pure-Pak<br />

machines. Moreover, many of them made a good living<br />

free from any uncomfortable competition.<br />

The new, light milk cartons could radically alter the<br />

picture, and established interests with monopolies to<br />

defend did not hesitate to mobilise marketing power,<br />

political friends and archaic legislation. In certain places,<br />

they managed to get the local health authorities to ban<br />

“paper bottles”, on the basis of undocumented theories<br />

regarding the carton’s adverse health effects.<br />

The carton sector – with Ex-Cell-O as the key player –<br />

fought a multitude of court battles during the years<br />

between the wars, both in the 48 states that made up the<br />

USA at that time, and within the federal legal system. An<br />

example from Chicago is illustrative: one of the city’s<br />

dairies wanted to offer its customers milk in Pure-Pak<br />

cartons, but the city health board denied approval of the<br />

new packaging and laid down a ban on sales, citing a<br />

stipulation from 1888 that volumes of milk under one gallon<br />

(3.8 litres) were only<br />

allowed to be sold in a<br />

“standard milk bottle”.<br />

After six years of<br />

court cases against the<br />

health board and the<br />

city’s major, conducted at<br />

all levels of the American<br />

legal system, it looked<br />

like the dairy and Ex-<br />

Cell-O were going to<br />

suffer a defeat. The final<br />

court ruling was that the<br />

city authorities had a legal right to make glass bottles compulsory<br />

if they so desired. But, while the trial was going on,<br />

the ban had not been legally binding. Sales of milk in<br />

paper-based packaging had been going ahead and had, in<br />

the meantime, reached a level of half a million units per<br />

day. It was blatantly obvious what consumers wanted. And<br />

since local elections were drawing near, Chicago’s mayor<br />

deemed it safest to make a u-turn: the challenging and<br />

hard-fought court victory was discreetly set aside and the<br />

words “standard milk bottle” were supplemented with “or<br />

other approved container.” And so Pure-Pak won the battle.<br />

Pure-Pak is perfected<br />

In addition to efforts at the legal and political levels,<br />

Ex-Cell-O also employed major resources in perfecting<br />

both the filling machines and the conversion machines for<br />

blanks. The blanks machines inherited from the American<br />

Paper Bottle Company used piles of paperboard plates as<br />

raw material in the same way as traditional printing houses.<br />

Ex-Cell-O developed new and effective rotation machines<br />

that inserted the raw material in the form of huge rolls<br />

and could continuously produce blanks at high speed.<br />

The cartons were also improved; amongst other things,<br />

Ex-Cell-O funded wide-ranging research to develop a new<br />

paper-based material that would make the packaging more<br />

hygienic and leak-proof.<br />

Another long-term and demanding development project<br />

centred on how the cartons should be opened. The product<br />

Ex-Cell-O took over in 1935 had no opening mechanism<br />

whatsoever; the consumer was directed to attack the<br />

carton with a knife or a pair of scissors. This was hardly<br />

satisfactory so Ex-Cell-O developed a solution in the form<br />

of a type of sealed ”tab” at the end of the carton’s gable –<br />

without quite managing to get it to work as it should. It<br />

actually took all of 18 years before the solution we all know<br />

was reached: the top part of the gable on the Pure-Pak<br />

could be bent back and folded out into a complete pouring<br />

spout, that is then folded back to close the carton. A brilliant<br />

solution, which, in terms of user-friendliness, is surpassed<br />

only by the plastic screw top. The concept itself<br />

was actually described in Van Wormer’s patent as early as<br />

1915 – but for a long time, it was impossible to create a<br />

gable that was both impermeable and easy to open,<br />

without using glue that produced an aftertaste or<br />

hazardous chemicals.<br />

Competition: A range of “paper bottles” were launched in the<br />

1930s; the picture at the top shows some of them. Pure-Pak<br />

(left) was the clear winner.

A major, powerful player<br />

In time, as the Pure-Pak system was further developed,<br />

Ex-Cell-O achieved ever-increasing success in the market,<br />

but the war years brought major supply problems. Not until<br />

the war was over could the really significant growth take<br />

place. A powerful, optimistic and technology-oriented USA<br />

stood ready to embrace any progress that made everyday<br />

life easier and better. Modern disposable packaging was of<br />

course right in its sights – and Pure-Pak in particular proved<br />

to appeal strongly to post-war, American housewives.<br />

The market share grew slowly but surely at the<br />

expense of both bottles and other beverage carton brands.<br />

By the mid-19<strong>50</strong>s, Ex-Cell-O had become a giant within<br />

disposable packaging. Nevertheless, it was the machines<br />

that were the company’s heart and soul; it didn’t matter<br />

whether they were used to build spaceships or fill milk<br />

cartons. Also, at that time, Ex-Cell-O only manufactured<br />

the machines themselves; from the very start, all blanks<br />

production was licensed to the paper factories and<br />

conversion specialists – in contrast to <strong>Elopak</strong>, for example,<br />

who chose to be a full systems supplier, responsible for<br />

both cartons and machines, and after a time, also for the<br />

equipment for distribution to the retail outlet’s refrigerated<br />

counter.<br />

Pure-Pak in the world<br />

During the initial post-war years, Ex-Cell-O had more than<br />

enough demand in the domestic market. During the 19<strong>50</strong>s<br />

however, the company slowly began to direct a little<br />

attention towards foreign players who wanted to take part<br />

in the progress. Moreover, the American military wanted<br />

their forces overseas to have milk in cartons, just like they<br />

were used to getting at home. Towards the end of 1956,<br />

Ex-Cell-O had six licensees outside the USA: three in<br />

Canada, one in Columbia – and two “overseas” in Belgium<br />

and Denmark.<br />

It was at this time that a Norwegian knocked on the<br />

door of the headquarters in Detroit. His name was<br />

Christian August Johansen. A cellulose engineer by<br />

profession, his mission was to secure a license agreement<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 11<br />

European tracks and sidetracks<br />

It was in the USA in 1906<br />

that the first serious<br />

attempts to put the milk<br />

carton on the market were<br />

made and it was also here<br />

that the beverage carton<br />

enjoyed its breakthrough a<br />

couple of decades later.<br />

However, this does not<br />

mean that there were no<br />

European inventors working<br />

on the case. A point to be<br />

made here is that Swedish<br />

Tetra Pak delivered its first<br />

filling machine in 1952, and<br />

with that started the sector’s biggest success story – but in<br />

actual fact, one Gustav Türk from Kronstad patented a<br />

paper-based beverage container as early as 1882. It was<br />

impregnated with a combination of fine limestone powder,<br />

aluminium-oxide and fresh blood serum – and was calmly<br />

forgotten. In 1929, the machine factory Jagenberg in<br />

Düsseldorf launched a gable top carton called “Perga Pack”<br />

– which enjoyed some degree of success, but fell prey to<br />

economic recession in the early 1930s. Production was<br />

however resumed in 1958, and taken over by SIG in 1988.<br />

The Satona Company in Leeds, England, also manufactured<br />

a “paper bottle” patented by the Dane, Carl Hartmann in<br />

1935, and the Norwegian engineer, Erling Stockhausen,<br />

patented a similar but improved carton and associated filling<br />

and sealing machine (picture). Stockhausen’s equipment<br />

was used on a trial basis by Agder Dairy in Kristiansand from<br />

1938 to 1940, reportedly with good results. The break-out of<br />

the Second World War brought further work to a halt.<br />

for Pure-Pak in Europe, and a filling machines agency. He<br />

was of course thrown out.<br />

But Christian August Johansen was not the type to give<br />

up so easily. It is said that he sat himself down on the<br />

steps and refused to move until the Ex-Cell-O management<br />

heard him out.<br />

In any case, it is a fact that he did eventually<br />

come home with both the license and the agency.<br />

And so begins the <strong>Elopak</strong> story – the subject of the<br />

next chapter.<br />

Vintage: Ex-Cell-O supplied Pure-Pak<br />

filling machines to all types of dairies,<br />

from the biggest to the smallest.

12 •<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> ÅR OG KLAR FOR MER<br />

Easy to do it yourself .....

A vision becomes reality<br />

No customers. No factory. No suppliers of raw materials.<br />

A product to which few Norwegians related, and which<br />

many regarded with scepticism. This was the state of<br />

affairs on the 11th of February 1957, the day A/S <strong>Elopak</strong><br />

Limited was founded. No-one can accuse the founders of<br />

lacking courage...<br />

It all began when the Norwegian cellulose engineer,<br />

Christian August Johansen, came home from the USA with<br />

a daring vision: a European license agreement for the<br />

American Pure-Pak carton and an agency for Pure-Pak filling<br />

machines. He had paid Ex-Cell-O in Detroit a lumpsum<br />

of <strong>50</strong>00 dollars; moreover, the American company<br />

were due a license fee of two percent of blanks sales. For<br />

his part, Johansen got a commission of around ten percent<br />

of machine sales.<br />

However – alone, he did not have the capital to get<br />

started. Johansen needed an investor and had already<br />

been in contact with Den norske Creditbank and Orkla,<br />

without success. In the spring of 1956, he was advised to<br />

contact Tiedemanns Tobaksfabrikk in Oslo. Here he found<br />

an interested audience in the factory owner Johan H.<br />

Andresen senior.<br />

‘Paper bottles’ … in Norway?<br />

Both directly before the war and around 19<strong>50</strong>, many of the<br />

Norwegian players were experimenting with carton packaging<br />

for milk. For a brief period, Fellesmeieriet dairy plant in<br />

Oslo supplied cream in cartons manufactured by a paper<br />

company in Sarpsborg, which were similar in appearance<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 13<br />

to Pure-Pak. And in 1953, the newspaper, Telemark<br />

Arbeiderblad, reported that Fellesmeieriet had plans to<br />

make the transition from glass to paper based packaging.<br />

But the newspaper was too quick off the mark and<br />

there was no shortage of reactions. ”...it is already apparent<br />

that the packaging will push up the price of milk to<br />

such an extent that normal sales will be out of the<br />

question,” remarked the manager of Skiens Meieribolag.<br />

He was supported by sober-minded men, who were enthusiastic<br />

about expressing their opinions in public debate:<br />

No, while disposable packaging was perhaps acceptable in<br />

America, it would not be in Norway. It would cost too much,<br />

and the minor inconvenience of washing and returning<br />

empty bottles wasn’t even worth mentioning...<br />

The factory-owner, Andresen, did not allow himself to<br />

be discouraged by this type of scepticism. The family firm<br />

needed new investment opportunities, and C. A.<br />

Johansen’s project was more closely scrutinised. After<br />

thorough calculations and analyses of the market<br />

opportunities, Johansen and a Tiedemanns representative<br />

travelled to Detroit. Here they met Ex-Cell-O Vice-President<br />

George Scott to confirm the agreement and elaborate on<br />

certain points.<br />

Tiedemanns swung behind the project. On the 11th of<br />

February 1957, A/S <strong>Elopak</strong> Limited was formally established.<br />

The name, an abbreviation for European Licensee of<br />

Pure-Pak, did not however arouse great enthusiasm at Ex-<br />

A handshake in Detroit: In early 1957, Christian August<br />

Johansen (on the left) and Ex-Cell-O’s George Scott agreed on<br />

the final details of the license agreement.

14 •<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE<br />

Cell-O, who thought the Norwegians were going too far.<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> had manufacturing rights only in Scandinavia, although<br />

it did have the sales rights for blanks in the whole of<br />

Europe, but not exclusively; there were already licenseholders<br />

in Denmark, Belgium and England.<br />

Nevertheless, the new company kept the name<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>. Tiedemanns became the principal shareholder with<br />

75 percent of the capital; C. A. Johansen got the remaining<br />

25 percent as payment for concept, rights and contributions<br />

before establishment. He also became the new<br />

company’s first CEO, and an agreement was entered into<br />

between <strong>Elopak</strong> and Johansen’s company regarding the<br />

sale of Pure-Pak filling machines.<br />

“It was quite a factory...”<br />

At the time, Tiedemanns had an available balance of NOK<br />

1.5 million. With this money behind them, the work of building<br />

a large, new production plant was set in motion –<br />

before <strong>Elopak</strong> was even formally established. The factory<br />

was located at Spikkestad in Southern Norway. The site<br />

was chosen because it was only a short distance from<br />

Hurum Paper Factory which, according to the plan, would<br />

be supplying the raw paperboard.<br />

The new building was erected in record time or, as an<br />

enthusiastic Drammens Tidende reported in their issue of<br />

23rd of November 1957: “It’s incredible, but it was in January<br />

this year that the groundwork began out at the <strong>Elopak</strong><br />

factory in Spikkestad. This was not a straight forward<br />

housing project. It was quite a factory – worth over 1.5<br />

million kroner. Today it is completely finished.” On the same<br />

day, the newspaper Fremtiden stressed that “a tour around<br />

the bright and beautiful factory grounds gives a good<br />

indication of just how far modern technology has come.”<br />

Both newspapers were impressed by the machines,<br />

from which “...paper milk bottles are virtually shot out”. And<br />

they had reason to be. <strong>Elopak</strong> had decided to go for an<br />

advanced, high-capacity, rotary machine – ambitions were<br />

riding high from the offset. The new company had<br />

committed itself to becoming a major supplier of integrated<br />

“packages” of machines and blanks – in contrast to many<br />

other players, among them Ex-Cell-O itself. “The parent<br />

Military inspection: The first <strong>Elopak</strong> cartons were to be used to<br />

supply milk to the American forces in Europe. The US Navy sent<br />

people to Spikkestad to ensure that everything went smoothly.<br />

company” in Detroit sold only the machines and left all<br />

blanks production to others on payment of a license fee.<br />

Fighting for a customer<br />

Now that <strong>Elopak</strong> had a factory the first personnel were<br />

recruited. But – there were still no customers, and the<br />

employees were carrying out odd jobs, such as painting<br />

the walls.<br />

As it turned out, the transition to paper-based materials<br />

was extremely difficult for the Norwegian dairies. At the<br />

time, they were in the middle of replacing long-necked and<br />

heavy, clear-glass bottles with a new type of bottle that<br />

was smaller, lighter and coloured brown, which provided a<br />

degree of protection against light and therefore against the<br />

unpleasant “sun-struck taste” that sometimes affected the<br />

milk in the summertime. This was already a major investment<br />

for the dairies. And then along comes <strong>Elopak</strong>, urging<br />

them to commit to “paper bottles” that will require further<br />

investment and will be more expensive! Thanks, but no<br />

thanks…it’s just too inconvenient.<br />

First-class equipment:<br />

Right from the start, the<br />

converter plant in<br />

Spikkestad had effective<br />

rotary machines with<br />

paperboard on rolls.

It was the American forces, stationed in Germany<br />

after the Second World War that came to the rescue. The<br />

soldiers received their daily milk in practical cartons, just<br />

like they were used to back home. The Dutch dairy company,<br />

Sterovita, was responsible for supply, based on<br />

blanks from the American-owned Dairy Pak. <strong>Elopak</strong><br />

decided to take up competition.<br />

However, closer investigation showed that Dairy Pak<br />

supplied blanks at way under the normal listed price, which<br />

formed the basis of <strong>Elopak</strong>’s calculations. This was a quite<br />

a let down. It called for a different way of thinking that was<br />

rooted in economics of scale – that is, where large volumes<br />

lead to low costs per unit. Moreover, the price of raw<br />

materials that had been used as the basis for negotiations<br />

with Hurum Paper Factory, simply had to come down.<br />

But Hurum had little faith in <strong>Elopak</strong> and, not least, in<br />

supplying liquid paperboard at the price the newly established<br />

factory would pay. The working relationship was terminated<br />

before it got off the ground, and <strong>Elopak</strong> chose to<br />

use liquid paperboard from International Paper in the USA.<br />

The offer was sent to Sterovita. And early in 1958, it<br />

was clear that <strong>Elopak</strong> had won its first customer – a contract<br />

for the monthly supply of between 40 and <strong>50</strong> million<br />

blanks over the course of one year.<br />

Another part of the story is that Dairy Pak was<br />

unhappy they had lost. The company’s Director and Sales<br />

Director made a personal appearance at <strong>Elopak</strong>’s Headquarters<br />

in Oslo, and threatened to drive the Norwegians<br />

into bankruptcy. It would later transpire that they had<br />

issued the same threat to Jyllands Papirværk (Schouw),<br />

who held the Pure-Pak license for Denmark, but without<br />

putting them into action. So <strong>Elopak</strong> chose to ignore the<br />

threat, and heard nothing more about it.<br />

Asker Dairy leads the charge<br />

In the meantime, the work to win customers from among<br />

the Norwegian dairies continued. It so happened that Asker<br />

Dairy planned to extend their capacity significantly, but had<br />

a serious space problem. <strong>Elopak</strong> demonstrated to the dairy<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 15<br />

Success: Asker Dairy was the first in<br />

Norway to go with Pure-Pak. Many<br />

customers gladly travelled the twenty<br />

miles from Oslo to get hold of milk in<br />

the new packaging.<br />

management, headed by manager Lars Gjul, how this<br />

could be resolved by making the transition to cartons from<br />

glass for certain stages of production. Both the manufacturing<br />

equipment and the packaging occupied significantly<br />

less space, and the dairy would be able to extend<br />

capacity without having to put up new buildings.<br />

That clinched the deal: on the 5th of February1958,<br />

Asker Dairy became the very first in Norway to fill Pure-Pak<br />

cartons with milk, and the first to make milk in cartons<br />

ordinarily accessible to Norwegian consumers.<br />

The event attracted wide press coverage as well as,<br />

according to the newspaper Nationen, several invited celebrities.<br />

Housewives stood in a queue outside, bursting with<br />

anticipation, to secure their share of the new miracle – and<br />

soon enough, many of them began to make the twenty<br />

mile trip from Oslo to Asker to buy milk.<br />

Furthermore, <strong>Elopak</strong> and Asker Dairy combined forces<br />

to make a smart marketing move: for the first month, the<br />

old bottles were not used. All products were filled in<br />

cartons which were, however, sold at the same price as<br />

bottled milk. Consequently, whether they wanted to or not,<br />

consumers became accustomed to the new packaging.<br />

Then, when the bottles returned, the housewives could –<br />

based on their own experiences – decide whether or not<br />

they wanted to pay the six øre the pricing authorities<br />

would accept as the additional price for cartons – and<br />

thus only carry home 1.08 kilos per litre of milk, instead<br />

of the heavier glass bottles; which in addition had to<br />

be washed out and carried back to the shop.<br />

There was no shortage of customers who<br />

thought that this was good value for money. And<br />

the numbers grew steadily until Asker Dairy was<br />

able to wind-up bottle-filling for good in 1967.<br />

The verdict of the consumers was clear<br />

and the success in Asker made a definite<br />

impression. Ten years after the<br />

establishment of <strong>Elopak</strong>, 39<br />

Norwegian dairies were filling<br />

Pure-Pak cartons with milk.

16 •<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> ÅR OG KLAR FOR MER<br />

The earlier the better …..

A global company takes shape<br />

Firmly established in Spikkestad, <strong>Elopak</strong> began to work<br />

intensively to add more Norwegian dairies to their customer<br />

list. After ten years, the number stood at 39; among them,<br />

some of the biggest dairies in the country. Now it was time<br />

to make the company’s international ambitions a reality.<br />

It would take an entire book to provide a reasonably systematic<br />

presentation of <strong>Elopak</strong>’s multifaceted development<br />

over the last fifty years – from when the first blanks left<br />

Spikkestad to today’s multinational company. We will have<br />

to content ourselves, over the following pages, with a range<br />

of themes and episodes; some important, others more of a<br />

characterisation. Several others could – and maybe should<br />

– have been chosen, but hopefully, this chapter will nevertheless<br />

provide some impression of <strong>Elopak</strong>’s journey to<br />

becoming a global company.<br />

Norwegian growth<br />

After <strong>Elopak</strong>’s successful debut in Asker, the market<br />

began to loosen up. More and more dairies realised that<br />

they had to provide customers with an alternative to the<br />

bothersome bottle. However, the dairies showed little willingness<br />

to pay, and <strong>Elopak</strong> had to operate within narrow<br />

price-margins and with low profitability. The organisation<br />

was small and did not have the money to employ more<br />

personnel – so the first years demanded a great deal of<br />

pioneering spirit and dedication from its employees, and<br />

patient far-sightedness from its owner.<br />

Daily life was not made easier by the fact that<br />

Ex-Cell-O was mostly concerned with selling machines in<br />

a burgeoning domestic market. License-holders in Europe<br />

played second fiddle and technical support was so-so.<br />

However, C. A. Johansen had recruited diligent service<br />

engineers, and they managed to deal with most situations<br />

on their own. Many of them were ex-naval engineers,<br />

used to improvising and able to give their all when it really<br />

mattered.<br />

Practical in the refrigerated display<br />

cabinet:<br />

The light, disposable cartons<br />

contributed to grocery shops in most<br />

places taking over the sale of milk.<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 17<br />

But, against all odds, <strong>Elopak</strong> managed to maintain a<br />

level of service with which clients were satisfied, and over<br />

ten years, 39 Norwegian dairies installed Pure-Pak<br />

machines. Contracts were won despite tough competition<br />

from alternative and cheaper solutions. A few dairies opted<br />

for milk in plastic bags, but the main competitor was<br />

Swedish Tetra Pak, with its tetrahedron shaped packaging<br />

that gave the company its name. Today, it is sold under the<br />

name “Tetra Classic”; during this period it was usually<br />

called “the triangle”.<br />

Both the packaging and the filling machine cost less<br />

than the equivalent Pure-Pak, and the small dairies,<br />

especially those in sparsely populated areas – where production<br />

volumes were small and transport of milk bottles<br />

disproportionately expensive – quickly adopted “the triangle”.<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> had, for its part, particular success in the<br />

bigger cities: it was unquestionably a major victory when,<br />

in 1960, the big Fellesmeieriet dairy plant in Oslo chose<br />

the Pure-Pak system.<br />

The key to <strong>Elopak</strong>’s success in the Norwegian market<br />

was Pure-Pak’s superior user-friendliness. Both “the<br />

triangle” and the milk bags were thoroughly unpopular<br />

with consumers. They were difficult to open and to pour<br />

from, and campaigns were launched in several places to<br />

replace them with the gable top carton.<br />

The bags quickly disappeared. “The triangle” also<br />

went on the defensive, and Tetra Pak realised that they<br />

needed to offer an alternative. Then, in 1964, the brickshaped<br />

Tetra Brik was launched – by locals it was immediately<br />

christened “the square”. But “the square” lacked<br />

the gable top carton’s stability, and many years would go<br />

by before it was given an opening mechanism which<br />

made the use of tools unnecessary. Norwegian consumers<br />

still preferred the gable top carton, and in the end,<br />

Tetra Pak therefore had to resort to the Pure-Pak<br />

imitation Tetra Rex, launched in Norway in 1967.<br />

Today the gable top carton is the dominant packaging<br />

form for milk and fresh juice in Norway, and <strong>Elopak</strong>

18 •<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE<br />

has maintained a clear, leading market position, in this<br />

anniversary year of 2007, with a market share of around<br />

60 percent.<br />

Out in the world – the hunt for paperboard<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> first established itself internationally in Finland –<br />

due to the necessity of having to find a secure and competitive<br />

supplier of raw materials. Initially, American paperboard<br />

was used, but this was not a permanent solution. C.<br />

A. Johansen had contacts within Finland’s biggest forestry<br />

group Enso-Gutzeit Oy, originally a Norwegian company<br />

founded by the Wilhelm Gutzeit from Drammen, which had<br />

since relocated to Finland. When Johansen contacted the<br />

company, they were right in the middle of constructing a<br />

new plant in Kaukopä, which could be developed to meet<br />

the Pure-Pak carton’s specifications.<br />

Parallel to this, <strong>Elopak</strong> saw great potential for cartoned<br />

milk in Finland, where, due to the destruction wrought by<br />

the Second World War and the Civil War, milk was mainly<br />

still sold in buckets. In 1959, <strong>Elopak</strong> and Enso-Gutzeit, with<br />

a <strong>50</strong> percent share each, created the company <strong>Elopak</strong> Oy.<br />

The company would sell machines to and provide a service<br />

for Finnish dairies, while Enso-Gutzeit would supply the<br />

domestic market with blanks, upon payment of a license<br />

fee to <strong>Elopak</strong> – and not least, supply the factory in<br />

Spikkestad with paperboard.<br />

In 1998, Enso-Gutzeit merged with Swedish Store<br />

Kopparsberg to form Stora Enso, which continues to be<br />

one of <strong>Elopak</strong>’s most important suppliers of raw materials<br />

along with Swedish Assi Domän Cartonboard and<br />

American International Paper.<br />

The great swedish milk war<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s next international venture was in Sweden. What<br />

happened here says a lot about consumer power and<br />

Four CEOs in fifty years<br />

powerlessness, and not least about the fierce struggle for<br />

the markets between <strong>Elopak</strong> and Tetra Pak.<br />

The Swedish co-operative dairy giant, Mjölkcentralen<br />

(now Arla), as interested in disposable packaging for milk as<br />

far back as the end of the 1940s. They had contacted<br />

Ex-Cell-O, who responded that they did not have the<br />

capacity to cater to civilian markets outside the USA.<br />

Mjölkcentralen therefore allied itself with Tetra Pak, who<br />

needed a partner to finance the work of developing the<br />

original tetrahedron shaped packaging, “the triangle”. The<br />

Swedish Dairies’ Association also contributed to the development<br />

work and later to the launch of the new packaging.<br />

The alliance would prove to play a major role in the<br />

competitive situation in Sweden. <strong>Elopak</strong> came to realise<br />

this after establishing its Swedish subsidiary in 1961, when<br />

it experienced Mjölkcentralen’s active efforts to prevent<br />

member dairies from choosing Pure-Pak. At first, just one<br />

dairy in Dalarne dared to break rank, the result of pressure<br />

from consumers who did not want their milk bottles to be<br />

replaced by “the triangle”.<br />

But the situation in Malmö was exceptional. Here, at<br />

the beginning of the sixties, there was real competition<br />

between three dairies, and a great deal of interest was<br />

aroused when the privately-owned Påhlssons Mejeri AB<br />

chose to invest in a Pure-Pak machine – and in one year,<br />

doubled its market share from 20 to 40 percent. Milk in<br />

Pure-Pak cartons was so popular that shops used them as<br />

loss-leaders, and when Påhlsson eventually began to<br />

“export” to Stockholm, the dairy had to buy in several Pure-<br />

Pak machines to cover demand. What’s more, the success<br />

in Malmö spread to the local dairy in Lund, Tetra Pak’s<br />

hometown. It is said that the head-quarters canteen had to<br />

serve milk in Pure-Pak cartons.<br />

Nevertheless, things got even worse when a market<br />

survey revealed that 80 percent of consumers preferred<br />

Throughout its <strong>50</strong> year history, all <strong>Elopak</strong>’s CEOs (Chief Executive Officers) have held the top job for long periods. The<br />

picture on the far left shows the portrait of Christian August Johansen who started and led the company from it was<br />

established in 1957 until 1967 – unveiled in the presence of (from the left) Arne Sunde (CEO from 1968 until 1979), owner<br />

Johan H. Andresen senior, his wife Marianne Andresen and Johansen himself. Today, the painting hangs in the company’s<br />

offices in Spikkestad. In the following pictures we see Eiulf Storm (CEO 1980-1996) and Bjørn Flatgård (1996-2007).

Pure-Pak, and were more than willing to pay a slightly<br />

higher price for it. More and more dairies chose to go over<br />

to the American-Norwegian carton, which from 1966 was<br />

manufactured at a dedicated plant in Sweden. At its peak,<br />

Pure-Pak’s market share was right up at 42 percent.<br />

As more and more dairies chose Pure-Pak, the<br />

Swedish Dairies’ Association decided they had to take<br />

action. The nasty competitor had to be stopped, and the<br />

organisation put pressure on member dairies to get them<br />

to replace Pure-Pak with Tetra Pak. But – consumers were<br />

having none of it! And with that, “the Swedish Milk War”<br />

broke out, a war that raged on many fronts: as petition<br />

campaigns, in local councils, as boycott demonstrations in<br />

support of Pure-Pak. The war enjoyed a great deal of coverage<br />

on radio and TV, (where Tetra Pak’s Hans Rausing<br />

spilled milk all over the table during a demonstration of “the<br />

triangle’s” pouring properties); it took on a legal dimension<br />

when <strong>Elopak</strong> took the competition authorities to court; at<br />

one stage, a smear campaign was launched involving<br />

claims that Pure-Pak’s wax-layer could be carcinogenic.<br />

The dairies divided into two camps, which after a while<br />

were hardly on speaking terms with one another. The dispute<br />

in Västerbotten was especially intense – it raged on,<br />

fuelled by large-scale public participation, over the entire<br />

period between 1977 and 1987 – with a level of heat that<br />

has become the subject of sociological studies.<br />

Part of the story is that consumer power didn’t cut it.<br />

Monopolies don’t have to take the wishes of consumers<br />

into account – but despite this, in 2007, <strong>Elopak</strong> still holds a<br />

30 percent market share in Sweden.<br />

European expansion<br />

Towards the end of the 1960s, <strong>Elopak</strong> began to expand<br />

beyond the Nordic region. The company held the license<br />

for Europe, but no exclusive rights. There were local license-holders<br />

in Denmark, Belgium, Italy, France and the<br />

United Kingdom. But, aside from in Denmark, and to a<br />

certain degree, the United Kingdom, they had not achieved<br />

a great deal.<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 19<br />

Fresh – or aseptic<br />

There are two main types of beverage carton, for fresh and<br />

aseptic products respectively. For fresh products the carton<br />

and the contents are normally not sterilised. This protects the<br />

fresh product’s taste and nutritional content. However, it has a<br />

shorter shelf-life, and the packaged product must be<br />

distributed in an unbroken refrigerated chain.<br />

Aseptic filling of milk takes place under sterile conditions and<br />

after ultra-pasteurisation, (UHT – Ultra High Temperature),<br />

which involves heating the content to around 140 degrees for<br />

a couple of seconds. Cartons for fresh products must be<br />

impervious to liquid; aseptic cartons must also be impervious<br />

to oxygen and other gases.<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> began cautiously with a small office in<br />

Germany, mostly in order to get a feel for the market. The<br />

first subsidiary outside the Nordic region was, however,<br />

established in France in 1967, the reason for this being<br />

that a couple of major contracts had been won there – as<br />

well as an order for three “Green Devil” aseptic filling<br />

machines (see fact box), the first three that Ex-Cell-O<br />

supplied in Europe.<br />

The name would turn out to be an omen: bacteria<br />

flourished in the presumably aseptic packaging, and<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s technicians failed to make the machines work. In<br />

actual fact, it is only in recent years that <strong>Elopak</strong> has<br />

become an aseptic supplier of any real size: it is fresh product<br />

packaging that has been the company’s main strength<br />

throughout most of their history.<br />

But the packaging of fresh milk requires high-quality<br />

raw materials, something which in turn demands that both<br />

the dairies and all distribution systems, from the farmer to<br />

the consumer, meet very strict requirements. This is not a<br />

problem if there is a tradition of adults drinking milk, like in<br />

North America, the Nordic region and a few other

20 •<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE<br />

Growth – around the world<br />

1957 Norway<br />

1959 Finland<br />

1961 Sweden<br />

1967 France<br />

1968 The Netherlands<br />

1968 Germany<br />

1969 Italy<br />

1974 Switzerland<br />

1981 Spain<br />

1982 Great Britain<br />

1983 Bahrain<br />

1983 The Netherlands, Elocoat<br />

1984 Switzerland, <strong>Elopak</strong> Systems<br />

1987 Ireland<br />

1987 USA<br />

1988 Portugal<br />

1988 Denmark<br />

1991 Austria<br />

1991 Czech Republic<br />

1992 Switzerland, <strong>Elopak</strong> Trading<br />

1992 Poland<br />

1992 Russia<br />

1992 Malaysia<br />

1995 France, Norester<br />

1996 Ukraine<br />

1997 Italy, Unifill<br />

1997 Saudi-Arabia, Joint Venture<br />

1998 Mexico, Joint Venture<br />

1998 Israel<br />

1999 USA, Scott Group<br />

1999 Finland, Elofin<br />

1999 Israel, Elocap<br />

1999 South Africa, Joint Venture<br />

2000 Canada<br />

2000 Switzerland, Plastic Systems<br />

2000 Germany, Elofill<br />

2000 China<br />

2001 Sweden, EDC<br />

2003 Great Britain, Plastic<br />

2003 Greece, Joint Venture<br />

2004 China, Souzhou<br />

2005 Serbia<br />

2006 Hungary<br />

2006 Luxembourg<br />

2006 Croatia<br />

countries. But in many parts of Europe and the world,<br />

packaged fresh milk is relatively rare, a premium product,<br />

with smaller volumes than of aseptically packaged milk.<br />

The Dutch are however a milk-drinking people. Moreover,<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> had excellent contacts in the country; the<br />

dairy company, Sterovita, had of course been <strong>Elopak</strong>’s<br />

very first customer. From an early stage therefore, the<br />

Netherlands became an area of commitment and has also<br />

acted as a bridgehead for further expansion into Europe.<br />

The first converter plant for blanks outside the Nordic<br />

region was constructed in the Dutch town of Terneuzen –<br />

which today also houses the factory that laminates<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s barrier materials onto the raw paperboard. <strong>Elopak</strong><br />

has maintained a solid position in the Dutch market for<br />

some time, a position that was further strengthened both<br />

locally, and in a range of other European countries when,<br />

in 2003, <strong>Elopak</strong> took over beverage carton operations of<br />

the Dutch packaging group Variopak.<br />

Ex-Cell-O’s decline<br />

But while <strong>Elopak</strong> expanded in Europe, things got worse for<br />

“mother” Ex-Cell-O in the USA. When <strong>Elopak</strong> got its Pure-<br />

Pak license in 1957, the Ex-Cell-O Corporation was a giant<br />

in the American market for milk packaging. Between <strong>50</strong><br />

and 60 percent of all the milk in the USA was sold in<br />

cartons, and of those cartons, between 60 and 70 percent<br />

were Pure-Pak cartons.<br />

But Ex-Cell-O’s primary business was machine<br />

construction. The company made manufacturing equipment<br />

and precision parts for a wide range of industries, and the<br />

Pure-Pak machines came into being in the same way as<br />

the machine factory’s other products – for the most part,<br />

using the same production lines. A lot suggests that<br />

Ex-Cell-O never saw itself as a part of the packaging<br />

industry; they thought in terms of “machines” not in terms<br />

of “packaging”, and had no discernible strategies for holding<br />

onto their fantastic position in the American milk market.<br />

After a while, patents began to expire resulting in<br />

declining license income and new competitors. Nevertheless,<br />

Ex-Cell-O did not commit to developing into a fullsystem<br />

supplier in order to secure new income streams, as<br />

both <strong>Elopak</strong> and Tetra Pak had done; neither did they form<br />

alliances with the big paper factories that manufactured<br />

blanks. A lack of proximity to the customer probably contributed<br />

to the fact that they did not manage to carry out<br />

product development, which would perhaps have secured<br />

the loyalty of the dairies.<br />

All these factors contributed to leaving the American<br />

market wide open to a new and aggressive competitor –<br />

the plastic bottle. It began to assert itself in the USA’s milk<br />

market at the beginning of the seventies. At the time, Pure-<br />

Pak still held over 70 percent of the carton market. By<br />

1979, plastic had taken over 45 percent of the total market,<br />

and this share rose rapidly into the eighties. Pure-Pak was<br />

in the process of turning into a marginalised phenomenon.<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> takes over<br />

At the beginning of the 1980s, <strong>Elopak</strong> was expanding<br />

internationally – and thoroughly frustrated by the fact that<br />

Ex-Cell-O had not managed to develop the new types of<br />

machines that clients were demanding. We have already<br />

mentioned that Ex-Cell-O had experimented with aseptic<br />

machines, but without success. <strong>Elopak</strong> chose therefore to<br />

instigate a joint venture with Liquipak in St. Paul,<br />

Minnesota. The goal was to develop an aseptic machine<br />

for Pure-Pak cartons – the project appeared extremely<br />

promising. In 1986, the first machine was ready to be<br />

publically presented at a trade fair in Paris, and was<br />

strategically placed in the exhibition hall the day before<br />

the opening of the trade fair.<br />

Then the bombshell was dropped: arch-rival Tetra Pak<br />

had bought out Liquipak – probably for the sole purpose of<br />

keeping <strong>Elopak</strong> out of the aseptic market. There the<br />

Swedish company held a near total monopoly, something<br />

they much preferred to hold onto.<br />

The Liquipak buy-out sent shockwaves through

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s management. What if Tetra Pak buys the rights to<br />

Pure-Pak too? Ex-Cell-O was obviously weary of the<br />

carton adventure and had intimated that they were thinking<br />

about selling up.<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> could not sit passively and watch something like<br />

this happen. Management was convinced that there had to<br />

be a way to exploit Pure-Pak’s international potential better<br />

than Ex-Cell-O had managed to do. In 1987, with the support<br />

of owner, Johan H. Andresen senior, <strong>Elopak</strong> stepped<br />

in and bought out Ex-Cell-O’s entire packaging division,<br />

including all rights to the Pure-Pak system worldwide. Here<br />

began <strong>Elopak</strong>’s journey to becoming a global player.<br />

And Ex-Cell-O? They still exist and make machine tools<br />

and automated manufacturing equipment for industry – just<br />

like they started doing in 1919. Today, the company is a<br />

part of German-American MAG Powertrain, itself a part of<br />

MAG Industrial Automation Systems.<br />

The American renaissance<br />

Ten years passed from <strong>Elopak</strong>’s take-over of all the rights to<br />

Pure-Pak until any serious attempt was made to win a position<br />

in the homeland of the carton. The region <strong>Elopak</strong><br />

Americas – with head-quarters in New Hudson, Michigan –<br />

has overall responsibility for all operations on the American<br />

continent and in the Caribbean. Here is also the factory that<br />

makes Pure-Pak filling machines, co-located with some research<br />

and development staff. The manufacturing of blanks<br />

takes place at plants in Montreal, Canada and Torreón,<br />

Mexico. The Mexican plant is one of <strong>Elopak</strong>’s biggest.<br />

Both the Mexican and the Canadian plants export significantly.<br />

Mexico supplies several South-American countries and<br />

the southern states of the USA, while Canada is strategically<br />

placed to supply Chicago, New York, Washington and the<br />

rest of eastern America south to Virginia. Additionally, several<br />

Caribbean countries are important export markets.<br />

Many Americans prefer plastic packaging for milk,<br />

which is now used for 80 percent of milk. The remaining<br />

20 percent nevertheless comprises large volumes, and<br />

therefore represents significant potential for Pure-Pak<br />

cartons. <strong>Elopak</strong>’s American personnel have moreover<br />

shown creativity and willingness to blaze new paths with<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 21<br />

unconventional products in relation to the gable top carton<br />

– such as sugar, syrup, bathing salts, plant fertiliser,<br />

chewing gum... and cartoned “liquid eggs” have been a big<br />

success with people who want to avoid breaking eggs to<br />

make an omelette.<br />

A global player<br />

When the first converter factory was built in Spikkestad, it<br />

was envisaged that in time, the plant could be extended to<br />

cover the whole of Europe’s demand for blanks. However,<br />

the dairy sector would turn out to be concerned with<br />

security of supply and would want blanks production to<br />

take place as close to the dairy as possible. Therefore,<br />

converter plants were constructed in several countries –<br />

until European integration, relaxation of tension between<br />

East and West, and not least safe, inexpensive transport<br />

options rendered the issue less pertinent. In the last few<br />

years, the tendency has been towards fewer and larger<br />

plants for production of blanks. Among those who have<br />

disappeared is the very first plant in Spikkestad.<br />

Despite <strong>Elopak</strong>’s international development, staff levels<br />

at the head-quarters in Norway have always been low. The<br />

dairy sector is characteristically local, and marked by<br />

tradition, politics and culture. For this reason, <strong>Elopak</strong> has<br />

chosen to opt for personnel “native” to the markets in which<br />

they have operated. Proximity to the customer has been<br />

the motto, so headquarters will just have to live with a few<br />

communication challenges.<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> has chosen to expand some markets through<br />

joint ventures with local players – today, Saudi-Arabian<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong> Obeikan, Envases <strong>Elopak</strong> in Mexico and <strong>Elopak</strong><br />

South Africa are successful examples of this. In other<br />

markets such as Japan, Korea and Australia, <strong>Elopak</strong> has<br />

built a foundation of license agreements with local partners.<br />

Regardless of the form the work takes, there is one<br />

condition for <strong>Elopak</strong>’s continued growth within a sector<br />

dominated by much bigger players: one must have added<br />

value to offer, and this must be based on attentiveness to<br />

the consumer’s needs and desires. This is why <strong>Elopak</strong>’s<br />

Research and Development holds the key to the future.<br />

More about this in the next chapter.<br />

Effective machines:<br />

A modern production line for<br />

blanks is a large machine. This<br />

one is from <strong>Elopak</strong>’s plant in<br />

Speyer, Germany.

22 •<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> ÅR OG KLAR FOR MER<br />

Prescription for hygiene.

Research for the breakfast table<br />

The ability to create new products is the key to the future<br />

for <strong>Elopak</strong>. This is why the company has one of<br />

Norwegian industry’s really intensive research and<br />

development departments, employing almost ninety<br />

people. And the range of skills spans far and wide:<br />

materials technology, food technology, microbiology,<br />

chemistry, physics, sensorics, industry design, logistics...<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s strategic decision to focus on the premium<br />

segment for beverage packaging posed a challenge for<br />

the company’s research and development resources.<br />

Packaging that should stand out on the shelves and<br />

provide added value for the product, must itself be of<br />

premium quality, in terms of both functionality and design.<br />

The R&D department quickly took up the challenge and<br />

over recent years the pace of <strong>Elopak</strong>’s innovation has<br />

attracted attention, both from customers and other<br />

players in the sector.<br />

The Technology Centre with its own dairy<br />

The foundation for the innovation of recent years was<br />

laid in 2000, with the opening of the <strong>Elopak</strong> Technology<br />

Centre in Spikkestad. Here is where the bulk of the<br />

company’s R&D resources are concentrated, with wellequipped<br />

laboratories for microbiology, chemistry, materials<br />

technology and analysis, quality control and sensorics<br />

– i.e. taste-testing. Moreover, the centre deals with<br />

market research and industrial design, and coordinates<br />

activities with the department in Detroit, other research<br />

institutes and specialist laboratories with which <strong>Elopak</strong><br />

collaborates.<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s Technology Centre distinguishes itself in that<br />

it houses an entire dairy – with equipment that receives<br />

milk straight from the cow – and large enough to serve<br />

the whole of the city of Drammen and half the county of<br />

Buskerud. The plant has government approval to process<br />

all food types. From time to time, it undertakes assignments<br />

for clients in emergency situations; however it is<br />

normally only used for testing packaging, machine parts,<br />

shelf-life and limited manufacturing for market testing.<br />

The Technology Centre also has a complete production<br />

line for testing blanks, and enough space to test<br />

twelve entire filling machines simultaneously. In the<br />

course of a year, between 20 and 30 machines come<br />

through the big hall in Spikkestad, some of which are<br />

built at <strong>Elopak</strong>’s own production unit in New Hudson in<br />

Michigan, USA; others by <strong>Elopak</strong>’s partner of many<br />

years, Shikoku Kakoki Co., Ltd. in Japan.<br />

Flexible and effective<br />

<strong>Elopak</strong>’s commitment to innovation has resulted in<br />

steadily increasing numbers of personnel within the R&D<br />

division. All are highly skilled in their fields, many holding<br />

PhDs.<br />

But even with one of Norwegian industry’s larger R&D<br />

departments, <strong>Elopak</strong> is a small player by international<br />

ELOPAK – <strong>50</strong> YEARS AND READY FOR MORE • 23<br />