Untitled - Galerie Kamel Mennour

Untitled - Galerie Kamel Mennour

Untitled - Galerie Kamel Mennour

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

This publications was published on<br />

the occasion of the exhibition<br />

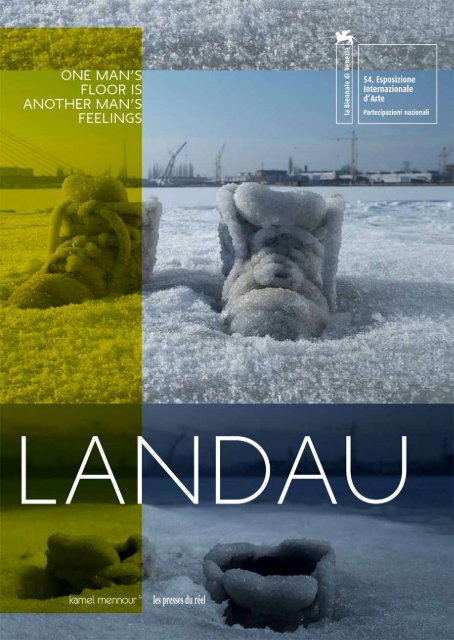

SIGALIT LANDAU:<br />

ONE MAN’S FLOOR IS ANOTHER<br />

MAN’S FEELINGS<br />

54th International Art Exhibition,<br />

La Biennale di Venezia<br />

Israeli Pavilion<br />

Curators: Jean de Loisy, Ilan Wizgan<br />

4 June — 11 November 2011<br />

KAMEL MENNOUR<br />

47, rue Saint-André des arts<br />

Paris 75006 France<br />

+33 (0)1 56 24 03 63<br />

galerie@kamelmennour.com<br />

www.kamelmennour.com<br />

LES PRESSES DU RÉEL<br />

35, rue Colson<br />

Dijon 21000 France<br />

+33 (0)3 80 30 75 23<br />

info@lespressesdureel.com<br />

www.lespressesdureel.com<br />

General coordination:<br />

Marie-Sophie Eiché<br />

Publishing coordination:<br />

Emma-Charlotte Gobry-Laurencin<br />

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS<br />

CULTURE & SCIENTIFIC AFFAIRS<br />

DIVISION<br />

THE EMBASSY OF ISRAEL IN ROME<br />

MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND SPORT<br />

CULTURE & ARTS ADMINISTRATION<br />

The Israeli Council of Culture and Art,<br />

Visual Art Section<br />

Steering Committee: Naomi Aviv,<br />

Dr. Vered Gani, David Ginton, Yitzhak<br />

Livneh, Dr. Shlomith Shaked.<br />

Coordinator: Idit Amihai<br />

Conception and Graphic design:<br />

Noam Schechter<br />

Graphic design: Avi Bohbot<br />

Photos adaptation to print: Artscan<br />

Translations and Editing:<br />

Genesis Translations (Arabic, English,<br />

French, Hebrew)<br />

Donald McGrath (English)<br />

Proofreading:<br />

Nathan Shalom<br />

Printing production:<br />

Seven7 – Liège<br />

info@seven7.be<br />

Printing:<br />

SNEL – Liège<br />

www.snel.be<br />

© 2011 Sigalit Landau for her works<br />

© 2011 kamel mennour, Paris, for the book<br />

© 2011 Jean de Loisy for his text and<br />

his interview of Sigalit Landau; Ilan<br />

Wizgan, Chantal Pontbriand, Hadas<br />

Maor and Matanya Sack for their texts and essays<br />

© Rechter Architects, Tel Aviv, for the historical<br />

plans and materials<br />

© 2011 Studio Sigalit Landau for the photographs<br />

© 2011 Marc Domage, Charles Duprat, Oded<br />

Leobel, Ohad Matalon, for their photographs of<br />

the works by Sigalit Landau<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this book may<br />

be reproduced by any means, in any media,<br />

electronic or mechanical, including motion picture<br />

film, video, photocopy, recording or any other<br />

information storage retrieval system, without prior<br />

permission in writing from kamel mennour gallery.<br />

ISBN : 978-2-914171-41-0

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

We would like to especially thank:<br />

INSTALLATION<br />

Pavilion commissioner: Arad Turgeman<br />

Art Project team: Patrick Ferragne,<br />

THANK YOU<br />

Imree and Eitan Ahoovai, Idit Amichai,<br />

Jamal Amira, Oded Arama, Guy Avidan,<br />

Contents<br />

Jean de Loisy, Ilan Wizgan,<br />

David Coutaz-Replan, Carla Casal<br />

Roee Azagi, Galit Azougue, Yossi Balt,<br />

Chantal Pontbriand, Hadas Maor<br />

Ribeiro, Yann Ledoux, Pierre Bamford,<br />

Alon Bar, Roni Bar, Shachar Bar On,<br />

and Matanya Sack<br />

Cyril Keim, Patrick Lauer<br />

Marcel Ben-Naim and all EMS Mekorot,<br />

Acoustic consulting and AV systems<br />

Projects team, Ofra Ben Yaakov, Ruti,<br />

GALLERIES<br />

design: David Huja<br />

Ben Yaakov, Gura Berman, Mordehai<br />

<strong>Kamel</strong> <strong>Mennour</strong>, Marie-Sophie<br />

Hydraulic Systems: Michele Marcato<br />

Boaz, Hanan Chait, Francesca,<br />

Eiché, Emma-Charlotte Gobry-<br />

Laurencin and all the kamel<br />

PRESS<br />

Cremasco and Giovanni Boldrin -<br />

Architects, Gabriel Dahan, Laila Darziv,<br />

Foreword<br />

mennour Gallery team (Paris, France)<br />

Brunswick team: Maria Finders,<br />

Jean-Baptiste de Beauvais, Amparo Del<br />

Mustapha Bouhayati, Emilia Stocchi,<br />

Gado, Xavier Douroux, Tamar Dresdner,<br />

Together . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Jean de Loisy . . . . 7<br />

Noemi and Nurit Givon and all the<br />

Lucie Narac<br />

Estee Du-nour, Amir Elstein, Eli Eshed -<br />

Givon Art Gallery team (Tel Aviv, Israel)<br />

Press in Israel: Eila Eitan<br />

Protec, Ofra Farchi, Roee Faygin - Mad<br />

Takin Ltd, Kibbutz Heftsiba, Yoram<br />

Liza Essers and all the Goodman Gallery<br />

VIDEO FILMS<br />

Feldhay, Asaf Gottesman, The<br />

team (Cape Town and Johannesburg,<br />

Production: Snir Merom Marinbach<br />

Gottesman Etching Center, Kibbutz<br />

Pavilion Installation Along with other Works . . . . . . 11<br />

South Africa)<br />

Photography: Amnon Zlayet, Yotam<br />

Cabri, Israel, Michael Gov, Vardit Gross,<br />

From<br />

Monique and Yaakov Har-El, Ronit<br />

SUPPORTERS<br />

Art: Shahar Bar-Adon<br />

Kahalon, Renana Kishon, Oleg Kulkin,<br />

Artis - Contemporary Israeli Art Fund<br />

Art Partners<br />

Dresser: Naama Preis, Galit Reich<br />

Gdansk Co-production: Carolina<br />

Ayelet Landau, Daniel Landau, Suzanne<br />

Landau, Richard and Jessy Leydier, Yona<br />

Texts<br />

Bracha and Roy Ben Yami<br />

Galuba<br />

Marcu, Federica Masolo, Artur and<br />

Yakov Borek<br />

Gdansk Co-production Arts: Darek<br />

Renne Mathias, Yoseph Mesilati, Edna<br />

The Freezing and Melting Point . . . . . . . . . . Ilan Wizgan . . . . 154<br />

Lily Elstein, Elstein Music and<br />

paciorek, Yuval Kedem<br />

Moshenson, Ambassador Daniel Nevo,<br />

Arts Center<br />

Video editing: Miki Shalom<br />

Ziv Nevo-Kulman, Prof. Mordechay<br />

Building a Different World: An Aesthetics of Fluidity . . . . Chantal Pontbriand . . 160<br />

Wendy Fisher<br />

Soundtrack Design: Yarden Erez<br />

Omer, Omanut Foundry, Kiryat Bialik,<br />

Dov Gottesman<br />

Israel, Christophe Pany, Yehoshua<br />

Space - Movement - Light: Israeli Pavilion in Venice . . . . Matanya Sack . . . . 170<br />

Asaf Recanati<br />

'Azkelon'<br />

Papish, Michel Pencreac’h, Charles<br />

Doron Sebbag<br />

Choreography: Maya Brinner<br />

Penwarden, Shmuel Rabin, Hila and<br />

Biography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173<br />

Performers: Artour Astman, Vadim<br />

Rani Rahav, Ofra and Bingi Raif, Amnon<br />

Dumesh, Alon Levi<br />

Rechter, Ruth Ronen, Colin Rosin, Eli<br />

Chronology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175<br />

Saar, Angela Scialom, Nathan Shalom,<br />

'Mermaids [Erasing the Border of<br />

Sharif Family, Zvika Shefi, Yoram Shilo<br />

The artist wishes to extend specials<br />

thanks to her team<br />

Azkelon']<br />

Performers: Maya Brinner, Shani Ben<br />

and Yael Ben Aroya, Ben Shoshan, Ruth<br />

Sonntag, Elisha Tal – i2d, Eli Topper,<br />

Translations<br />

Yotam From [studio and show<br />

Haim, Shlomit Corry, Tamar Linder,<br />

Nimrod Wizgan, Hervé Woltèche, Aviv<br />

photographer/horse power]<br />

Sharon Vazanna<br />

Yaakov – Van Colmjon, Shlomit Yarkoni,<br />

French . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 179<br />

Tsachi Hackmon [Dead Sea Captain]<br />

Vitaly Yermakov, Shlomo Yitzhaki<br />

Nadav Korati [installation/energy]<br />

'Salt Bridge Summit' and 'Laces'<br />

Arabic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221<br />

Itamar Mendelovitch [wood and paint<br />

Directors and casting: Tamar Linder and<br />

specialist]<br />

Beryl Schennen<br />

Hebrew . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239<br />

Nir Moses [studio doctor]<br />

Actors: Eden Yaakov — Van Colmjon<br />

Eyal Segal [designer/project<br />

(Girl), Mitka Ben-Zion, Zach Cohen,<br />

coordinator]<br />

Michal Cohen Paryente, Ishai Golan,<br />

Noga Shlomi [production/P.Angel]<br />

Eran Invanir, Keren Mor, Kais Nashif,<br />

Nathan Brand, Alon Neuman, Menashe<br />

Extra special super thank you<br />

Noy, Ali Suliman, Elisha Tal<br />

Arad, Eyal, Ilan, Jean, <strong>Kamel</strong>,<br />

Marie-Sophie, Noam, Noga

7<br />

IN LOVING MEMORY OF<br />

DOV GOTTESMAN<br />

A TRUE FRIEND OF THE ARTS<br />

Together<br />

Jean de Loisy<br />

Robert Smithson's imperative, calling on every artist to “investigate the spirit of<br />

pre- and post-history” and go “where the far future meets the far past” *, precisely<br />

corresponds to Sigalit Landau's stubborn persistency in remaining on the banks<br />

of the Dead Sea. She has worked there for years, at the lowest place on earth, in the<br />

desolate landscape tormented by the sulfur and fire sent by the biblical God, wounded<br />

by history, injured as a result of a longstanding ecological disaster, a hotspot still<br />

wracked by numerous regional conflicts. Every movement under this merciless<br />

sun has a price, and the movements performed must be economical. They must be<br />

efficient and sufficiently meaningful to justify the fatigue they cause. Similar to<br />

these efforts that are accurately forecast, all of the artist's works are characterized<br />

by extreme compression or compaction. A painting, a photograph, an object that<br />

underwent transformation are often sufficient to convey a range of meanings or fix<br />

a metaphor that immediately echoes in our mind. For example, a net submerged in<br />

this sterile sea, that is later pulled out covered with salt crystals or a barbed wire<br />

encircling a woman's belly, her own—a recent sculpture and old video that became<br />

a collective icon.These two works, that were created ten years apart, bear a universal<br />

symbolism whose power reflects the sites in which these images were created.<br />

Without chatter, psychology, or an artist's narcissism, only quiet elegance and power.<br />

These are powerful objects that impact the spirit as triggers. There is no doubt that<br />

they appeal to our conscience, pose before us the most essential questions, yet<br />

without preaching or reproach, except for the pre-planned impact of their laconic<br />

presence that effects us.<br />

Sigalit Landau reacts like a poet to the warning signs of her time, as did, in their<br />

own ways, artists so different from her such as Goya or Beuys. But Sigalit Landau does<br />

not do this by emphasizing the tragic spectacle of destruction or barbarism, or by<br />

political actions such as creating a student party for political change. Instead, she<br />

simply turns up the volume on reality and specific situations. The other, water, work,<br />

the community or the distribution of resources. Thus, while invoking big themes<br />

and subjects, Sigalit Landau succeeds in reducing the distance created by daily<br />

reality through constant repetition. The same issues, that have become abstract due<br />

to their treatment by the media, find new links and connections to our basic daily<br />

experiences: carrying, picking, fishing, swimming, playing, living, remembering.<br />

They are expressed simply in her video works, often consisting of a single, fixed shot,<br />

without any apparent editing, or through her figurative sculptures that succeed in<br />

* Robert Smithson, “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects”, Artforum, September 1968

* * *<br />

I am attracted to places that are disregarded, hideouts,<br />

architectural ‘pockets’, informal and ‘in-between’ spaces.<br />

I made a hole in the wall of this hidden space and re-invented it<br />

so that I could place the heart of my installation (the pump) in<br />

the ‘intestine of the building’, which was full of earth and<br />

debris. I worked as hard as I could to take out this earth… It felt<br />

like an escape, and a search for water… also like a release from<br />

‘territorial constipation’.<br />

Sigalit Landau interviewed by Jean de Loisy

Ground<br />

floor<br />

KING OF THE SHEPHERDS AND<br />

THE CONCEALED PART<br />

Metal pipes, water<br />

1120×220×860 cm

32<br />

Scale of In-Justice, 1996-2005<br />

→<br />

The work was first molded by<br />

incapable of ever reaching<br />

At a later phase, the work was<br />

the artist using readymade scales<br />

equation and balance. The final<br />

cast in an edition of three in a<br />

made of bronze.<br />

object, delicate and beautiful yet<br />

unique way, using gold, silver<br />

Hammering one of its plates to<br />

sinister, is an acute statement<br />

and bronze.<br />

such an extent that it became<br />

regarding the basic human<br />

convex instead of concave, its<br />

condition. Landau’s insistence<br />

surface resembling the topography<br />

on addressing the seemingly<br />

of Landau’s earlier work Resident<br />

impossible and making it at least<br />

Alien I (1996), the process finally<br />

thinkable, if not actually feasible,<br />

created an irregular set of scales,<br />

is a recurrent and important<br />

practically unable to contain<br />

theme characterizing her work<br />

and scale, and thus intrinsically<br />

throughout the years.<br />

WATER LADDER II (NADAV)<br />

Metal Pipes, metal tubes, water<br />

meters and bricks. 120×540×28 cm

* * *<br />

I filmed people playing the “knife” game — it is also called<br />

“Countries” — and I have titled this video Azkelon, a hybrid<br />

of two names: ‘Gaza’ (Aza in Hebrew) and ‘Ashkelon’. The two<br />

towns almost share a beach but are separated by a border; the<br />

Gaza strip is one of the most overcrowded districts of refugee<br />

camps in the world. In the 1950’s, Ashkelon was populated by<br />

many Jews from Arab countries who were housed in temporary<br />

immigrant camps, and it is still a marginalized part of Israel.<br />

From my point of view, youth on the two sides play this “game”,<br />

and where there is play, it means there is still a lot of life; it is an<br />

agreement to certain simple rules. They may win, they may lose;<br />

it is not an impossible interaction.

* * *<br />

On a beach on the border between Gaza and Ashkelon: three<br />

women repeatedly fall off the waves. They slowly scratch the<br />

sand of the beach with their hands and nails, as they are pulled<br />

back to the waves. The video is projected on the floor of the<br />

ground level (and can be viewed from the third floor). This is not<br />

a game; it is an imitation of nature, a “reaction” mark I made<br />

on the beach of Tel Aviv during one of the slightly frustrating<br />

rehearsals with the “knife” players.

70 71<br />

Barbed Hula, 2000<br />

Barbed Hula, 2000<br />

→<br />

In this video the artist is seen<br />

viewer's gaze, the act accumulates<br />

Bound by the hoop's diameter<br />

spinning a hula-hoop made of<br />

a highly sensual aspect as well.<br />

and her physical stamina, she<br />

barbed wire around her bare<br />

The work fuses the notions<br />

seems to try and reach beyond<br />

body and against the calm back<br />

of freedom and constraint,<br />

the bodily constraint, a familiar<br />

view of the Mediterranean Sea.<br />

manifested on the individual body<br />

goal practiced in various cultures<br />

The barbed wire, a material that<br />

but symbolically relevant on a<br />

in different manners, as in the<br />

immanently relates to restriction<br />

much larger scale. Although cut<br />

Sufi swirl dance for example.<br />

and enclosure, is used by the artist<br />

out by the camera's frame, it is<br />

Landau herself regarded the<br />

to develop a repetitive centrifugal<br />

obvious that the artist's face is<br />

work as a personal and senso-<br />

movement heightened by velocity;<br />

turned upwards, and that she is<br />

political act, concerning invisible,<br />

a durational act involving ecstasy<br />

consumed by the action, elevated<br />

sub-skin borders.<br />

and pain. Bluntly exposed to the<br />

into a different mental realm.

80 81<br />

* * *<br />

The fishing net evokes the native Jaffa fishermen, who sold me<br />

their fishing nets. They are people of peace who all share the<br />

same sea, that is sometimes sweet and kind and sometimes<br />

demanding, but they live of what grows under its blue waves;<br />

not in the Dead Sea’s bitter and heavy solution, like me. My<br />

(their) fishing nets catch magnificent crystals. It is beautiful but<br />

sterile. These objects confront the fishing net that re-invokes<br />

fertility and life, with the deadly grasp of the salt.

* * *<br />

I made shoes covered by heavy salt crystals — by suspending<br />

them in the saline waters of the Dead Sea. After this, I took<br />

them to a frozen lake in the middle of Europe and placed them<br />

on the ice. Each shoe melted a big hole in the ice. At night, they<br />

finally fell and drowned in the sweet waters of the lake. From<br />

the heights of the third strata of the pavilion, they fall and dive<br />

downwards, burdened with history and gravity.

98 99<br />

SALTED LAKE (SALT CRYSTAL<br />

a prolonged gaze at the image<br />

they stand, causing their own<br />

shoot the video in Poland, in the<br />

SALT CRYSTALLISATION PROCESS<br />

process in these conditions can be extremely fast.<br />

time system, a different logic, another planet. It<br />

SHOES ON A FROZEN LAKE),<br />

reveals the change of light, from<br />

sinking deeper and deeper into<br />

revolutionary city of Gdansk,<br />

Some materials encourage this reaction — and<br />

looks like snow, like sugar, like death's embrace;<br />

2011<br />

light to dark, and some movement<br />

the frozen snow and finally, into<br />

creates a tantalizing work that<br />

One month a year. From the end of July till the<br />

formations are ripe within days, other surfaces<br />

solid tears, like a white surrender to fire and water<br />

of cars on the string bridge at the<br />

the water of the lake beneath it.<br />

touches upon collective memory<br />

end of August, when the Dead Sea is impossible<br />

reject/postpone the process of crystallisation. We<br />

combined. Each season I swear — it is my last<br />

The image revealed in this video<br />

back. Placed on the frozen waters<br />

As in additional works by Landau,<br />

and pain.<br />

to visit and totally unbearable to enter, this is<br />

hang our objects, forms and materials carefully<br />

attempt, and I will never return… and look back.<br />

seems at first glance to be still: a<br />

of Gdansk's lake, the shoes are<br />

this work manifests her informed<br />

when the lake gives its best crystals. We leave<br />

with weights and floats, not knowing what kind of<br />

pair of heavy shoes, which look<br />

actually a sculptural object made<br />

use of contradictory forces such<br />

Tel Aviv at around 3:00 in the morning to arrive<br />

reaction-interaction will take place in the next days,<br />

as if they are totally covered<br />

by the artist employing her unique<br />

as stillness and movement, aridity<br />

one hour before the sun rises, via Jerusalem and<br />

and what we will find when we come back. The<br />

with ice, placed on a vast open<br />

immersion process in the Dead<br />

and moisture, sweet and salty<br />

the Judea desert. We try to prepare everything in<br />

process of exiting the sea with the heavy objects<br />

plane of frozen snow while in the<br />

Sea. Thus, the shoes are actually<br />

water, etc.<br />

the days before the journey, so that no surprises<br />

involve many more strong hands… A pair of bicycles<br />

background a shipyard and a large<br />

covered with salt crystals, which<br />

Infused with historical and political<br />

occur to us while in the water, costing time and<br />

that enters the sea (sealed and treated against<br />

string bridge stretch out. Only<br />

slowly melt away the ice on which<br />

awareness, Landau's choice to<br />

energy we lack… Even at 5:00 am the water<br />

rust) at 10 kg can accumulate 150 kg of salt within<br />

is boiling hot, burning every slight wound; the<br />

few weeks. Over the years, I learnt more and more<br />

potion clings to the body at once, forming instant<br />

about this low and strange place. Still the magic is<br />

crystals on men’s body hair and hurting women’s<br />

there waiting for us: new experiments, ideas and<br />

private parts. You either love it or hate it. The<br />

understandings. It is like a meeting with a different

104 105<br />

DeadSee, 2005<br />

→<br />

The work was shot from a bird's<br />

their red raw meat out. Trapped<br />

elevates higher and higher up. At<br />

eye point of view. It begins with<br />

inside the spiral chain is the<br />

some point during the process<br />

a hauntingly beautiful image,<br />

artist, floating along with it, her<br />

of unraveling, the artist's body<br />

inexplicable at first glance, created<br />

bare body adjacent to the green<br />

reaches the outskirts of the slowly<br />

by a chain of 500 watermelons,<br />

watermelons, her arm reaching<br />

diminishing raft, and she is seen<br />

connected by a 250 meters cord,<br />

out to the burning red wounded<br />

holding on to the watermelons<br />

forming a six-meter sweet spiral<br />

area of the raft. As the cord of the<br />

chain as if holding on to her life.<br />

raft floating in the saturated saline<br />

spiral is pulled outward, away from<br />

Alluding to Robert Smithson's<br />

waters of the Dead Sea. Amongst<br />

the center, the chain unravels,<br />

mythical work The Spiral Jetty<br />

the hundreds of watermelons<br />

gradually becoming a thin green<br />

(1970), this work combines the<br />

linked in the chain, some are<br />

line abandoning the frame, and<br />

conceptual with the sensual, land<br />

broken and radiate the shine of<br />

the point of view of the camera<br />

art with body art, sugar with salt.

* * *<br />

In this mischievous act she is relating to a role, a dance, a tribe…<br />

to their past and to her future. As she connects the footwear to<br />

each other — the participants surprise her, and leave the table<br />

barefoot, as refugees, as prisoners of war; achieving nothing.<br />

As the tubes carry water, the laces carry her yearning for<br />

their agreement.<br />

She is one stratum under the “real” level, under the table of<br />

the middle floor — so she is leading us back to the enclosed<br />

space below her. She is a fallen Joseph in the pit, and the Master<br />

of an unfinished or rather unstated ceremony. Like Joseph<br />

she is a dreamer.

128<br />

Project 87, 2008<br />

129<br />

Barbed Salt Lamps, 2008<br />

→<br />

Project 87, shown at the MoMA,<br />

Sea, the process of infused the<br />

which continued to operate and<br />

featured two of Landau's video<br />

works with elusive qualities, highly<br />

crackle in the works even as they<br />

works, Barbed Hula (2000) and<br />

beautiful, but also carriers of<br />

were exhibited.<br />

DeadSee (2005) alongside a<br />

loss and destruction. The waters<br />

stunning installation of barbed salt<br />

of the Dead Sea — the lifeless,<br />

lamps hung from the ceiling of<br />

lowest place on earth, in which<br />

the exhibition space. Each of these<br />

the works were immersed in one<br />

lamps was crafted by Landau in<br />

state, and from which they were<br />

barbed wire and then immersed<br />

pulled out several months later<br />

in the Dead Sea for a different<br />

in a very different state — set<br />

period of time. Accumulating the<br />

an anticipated yet uncontrolled<br />

salts and minerals of the Dead<br />

organic process in motion,<br />

BARBED SALT LAMP<br />

2009

134<br />

135<br />

Dead Sea Salt Crystal Bridge<br />

Study for the Salt Bridge Project, 2011<br />

→<br />

The salt bridge proposal is<br />

The Dead Sea area distinctly<br />

engaged in the commercial,<br />

a unique, somewhat utopic<br />

demonstrates the tension<br />

cultural and environmental<br />

proposal, for building a bridge that<br />

between ecological and<br />

affairs on both the Israeli and<br />

will connect Israel and Jordan at<br />

economical forces and the way<br />

Jordanian sides for the past 12<br />

the southern part of the Dead Sea.<br />

these are bound to political<br />

months. The project is yet to<br />

The proposal, visually consisting<br />

currents. Landau's aim, through<br />

be approved and to go through<br />

of a salted walking trail, salt pillars<br />

this proposal, is to create a work<br />

final design phases and detailed<br />

structured around metal pipes<br />

of art that will not only span the<br />

structural engineering.<br />

and an actual constructed and<br />

Jordan Israeli border and serve<br />

crystallized salt bridge, is based on<br />

as a symbolic manifestation of<br />

the artist's seven years of personal<br />

coexistence, but will become a<br />

experience, her research into<br />

focal point that bridges political,<br />

the crystallization processes and<br />

economical and ecological gaps.<br />

the development of various salt<br />

Landau has been conducting<br />

objects through a special dipping<br />

meetings with various economic,<br />

method in the Dead Sea.<br />

industrial and political figures<br />

SALT FABRIC<br />

2009

154 155 155<br />

The Freezing and Melting<br />

Point<br />

Ilan Wizgan<br />

The Israeli Pavilion in the Giardini at the Venice<br />

Biennale, with its distinctive history, geography and<br />

morphology, is the starting point for Sigalit Landau’s<br />

project. The pavilion, first conceived in the late 1940s, was<br />

designed by Israeli architect Zeev Rechter, and unveiled<br />

in the mid 1950s. Venetian authorities allocated a site for<br />

the pavilion on the banks of the Giardini Canal, next to<br />

the American Pavilion. Among the varied architectural<br />

styles of the national pavilions in the Biennale Gardens,<br />

between neo-Gothic and neo-Classical structures,<br />

Rechter chose to design a Modernist pavilion in the<br />

spirit of the Bauhaus and the International Style that<br />

characterized pre-State construction in Israel.<br />

The pavilion was designed as a three-storey villa,<br />

with a large, sealed, windowless façade, as if it were<br />

turning its back on the access path and to the other<br />

pavilions; in contrast, the rear of the structure features<br />

a huge window and a pleasant and inviting courtyard<br />

surrounded and concealed by trees. Its location, shape,<br />

and intrinsic worldview seem to echo the collective<br />

Israeli consciousness and the geo-political condition<br />

of the State of Israel (the proximity to the American<br />

Pavilion, the closeness to the sea, the Egyptian pavilion<br />

across the canal…). Sigalit Landau took all these factors<br />

into account while planning her new installation in the<br />

pavilion. Moreover, the historical period in which the<br />

pavilion was designed and constructed coincides with<br />

the period Landau’s works has referred to in recent years,<br />

the decade that shaped the Israeli homeland politically,<br />

demographically, ethnically and architecturally.*<br />

As part of her preliminary preparations, Landau<br />

researched the circumstances of the pavilion’s<br />

* For more information on the history of the Israeli Pavilion and<br />

its design and construction process, see Matanya Sack’s article,<br />

page 170.<br />

conception, burrowed in the archives of its architect,<br />

and dug up every yellowing piece of paper that might<br />

possibly shed light on the process, from the stage of the<br />

initial concept (prior to the establishment of the State of<br />

Israel) to the final design. Her point of departure opposes<br />

and defies the perception of withdrawal and isolation<br />

underlying the original design and its disregard for the<br />

display requirements of art works—expressed in the<br />

choice of the unstable southern light, instead of the<br />

more favorable northern light, a far too low ceiling above<br />

the entrance floor, a “floating” upper floor with only two<br />

supporting walls, and a free-standing spiral staircase. In<br />

her typical way, Landau does not refer to the structure as<br />

self-evident and as a reality she must take into account.<br />

She believes that the space must serve the work, and<br />

not the other way round. Although the concrete space<br />

is always the starting point which gives rise to the<br />

work, from the moment the fundamental decisions are<br />

made and the framework is planned, the work develops<br />

and “requests” compromises and changes from the<br />

building, sometimes including the tearing down of<br />

walls, the sealing of windows, the digging of holes,<br />

excavations and the like.<br />

Ground Floor<br />

Upon entering the exhibition, the visitor finds himself<br />

in a space reminiscent of a machine room. At one end,<br />

between the two stairwells, a video work is projected<br />

onto the floor. The work depicts a group of men playing<br />

the Countries game—marking an imaginary rectangle<br />

in the sand, throwing knives into it, and dividing the<br />

territory between them. The space is interlaced with an<br />

extensive system of water-meters and pipes connected to<br />

each other, rising and falling, converging at the other end<br />

of the space; there, they cross its borders and disappear<br />

into an aperture in the wall, while crossing another<br />

space that is caged between the pavilion’s floors, where<br />

they end—or perhaps begin—their journey in the large<br />

canal adjacent to the pavilion. Concealed in the caged<br />

space is a pump, the beating heart of the system, which<br />

propels the water through the pipes like blood through<br />

the body’s arteries. The water flows in a closed circle,<br />

incessantly originating from and returning to the canal,<br />

leaving faint sounds inside the space, the only evidence<br />

of its hidden movement.<br />

The sea, therefore, causes life to flow into the<br />

sculptural system, but is this indeed life? The water<br />

returns to the sea without having been absorbed, neither<br />

by the body nor by the ground; this is a cyclic and<br />

barren action that does not feed or nurture anything.<br />

This work brings to mind the Dead Sea Project by Pinchas<br />

Cohen-Gan, an Israeli artist who, in the 1970s, created a<br />

fascinating chain of actions of a conceptual and political<br />

character. In 1973, he inserted plastic sleeves full of fresh<br />

water and live fish into the Dead Sea. His work dealt with<br />

the questions of foreignness, immigration and survival<br />

under hostile conditions, issues that are also expressed<br />

in earlier works by Landau. Connecting the pavilion to<br />

the canal through the pipes emphasizes its location on<br />

the seashore—at the edge and at the border. This is a<br />

location which, as already mentioned, reminds us of the<br />

geographical location of the State of Israel in the Middle<br />

East, and of the dual and contradictory implication it has<br />

for to the Israeli consciousness—on one hand, a space<br />

open to the horizon, with all the cultural and economic<br />

opportunities it embodies and, on the other hand, a sense<br />

of crammed congestion between the mountains and the<br />

sea, in the shadow of the constant threat of being pushed<br />

into the sea by its enemies. This connection also brings<br />

to mind large infrastructure projects that are part of the<br />

State of Israel’s vision, some of which have been realized,<br />

such as the National Water Conduit that supplies water<br />

from the Galilee to the arid south, while others are still<br />

plans for the future, perhaps practical and perhaps<br />

fantasy, such as constructing a canal between the Red<br />

Sea and the drying up Dead Sea.<br />

The presence of water in the pavilion serves as a<br />

metaphor for the movement of life and time, and for the<br />

irresponsible waste of both which too often characterizes<br />

human conduct, as expressed, among others, in the Israeli-<br />

Arab conflict. In this context, water is also an existential<br />

issue, an acute problem characteristic of the Middle East<br />

region that suffers from a shortage of rain and of fresh<br />

water sources. The water-pipe installation is reminiscent<br />

of the pumping stations of “Mekorot” (literally ‘sources’),<br />

the National Water Company, scattered all over Israel in<br />

a desperate attempt to suck the water hidden deep in the<br />

ground. Connecting the Israeli Pavilion with the Venetian<br />

sea, and the very fact that the exhibition is held in Venice,<br />

emphasizes the disparity between an arid region and one<br />

in which water abounds, and further raises awareness of<br />

the issue of natural resources and their allocation. This<br />

issue stresses the mutual dependence of human beings,<br />

the crucial importance of taking the needs of others into<br />

consideration and, as expressed in the spirit of the entire<br />

exhibition—the need for sincere and self-interest-free<br />

dialog in order to solve shared problems.<br />

As mentioned, Landau converted the entrance and<br />

reception space into a “machine room”. Typically, a<br />

machine room is a concealed space in a structure, an area<br />

responsible for the functioning of the entire system; as<br />

long as it continues to operate properly, the system is not<br />

aware of it and is not exposed to it. Attention is directed<br />

to it only in case of a breakdown or a mishap, just as<br />

we become aware of our bodies, our internal organs,<br />

only when they transmit pain or do not function. The<br />

exposed machine room, therefore, hints at the need for<br />

catheterization, or even for real open heart surgery, in<br />

order to bring relief and resolve the problems addressed<br />

by the exhibition, including inequality between people,<br />

the violation of the ecological equilibrium, and the<br />

distribution of resources and wealth among nations.<br />

An interesting point of reference in the construction<br />

of the water-meters and pipes installation is the King of<br />

Shepherds sculpture by Yitzhak Danziger, and perhaps also<br />

his Water Conduits. Danziger, an Israeli artist who preceded<br />

Landau by two generations was, like her, an artist with<br />

historical/mythological, social and ecological awareness,<br />

from whom she has already drawn inspiration in<br />

previous installations, particularly in The Endless Solution<br />

exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 2005. In this<br />

highly charged and complex exhibition, with overt and<br />

subtle hints in reference to the Holocaust of European<br />

Jewry, Landau created a remote, hostile life environment<br />

populated by a toiling community engaged in overcoming<br />

disaster, in survival and in a new beginning. The huge<br />

space underwent a transformation to simulate another<br />

place and another time: the place—the Dead Sea area,<br />

the time—could not be accurately dated, but modern<br />

signs (old cars, bicycles, machines) hinted at our period,<br />

sometime in the twentieth century. The name of the<br />

exhibition and additional clues planted in this enormous<br />

installation pointed to the middle of the century—World<br />

War II and the Holocaust. Images layered and charged<br />

simultaneously with local and universal meanings, both<br />

historical and contemporary, filled the space and shook<br />

the viewer: the Dead Sea, the Sea of Death that destroys,<br />

yet also purifies; images of crucifixion, of sacrifice, of<br />

redemption. One of the elements of the exhibition was<br />

a structure reminiscent of a volcano, a bustling beehive,<br />

or a crematory. The similarity of form with Danziger’s

160 161<br />

Building a Different<br />

World: An AeSThetics of<br />

Fluidity<br />

Chantal Pontbriand<br />

The community is not the site of Sovereignty.<br />

It is what shows itself by being shown.<br />

It includes the exteriority of being that excludes it. 1<br />

This definition of the question set out on page twentyfive<br />

of the booklet that Maurice Blanchot devoted to the<br />

idea of community, will guide us through the work of<br />

Sigalit Landau, an Israeli artist whose work appears in<br />

her country’s pavilion at the 54 th Venice Biennale. The<br />

unavowable community—La Communauté inavouable is the<br />

title of Blanchot’s book—is a perpetual beginning and<br />

requires that one pays constant attention to the question<br />

of what brings people together and can potentially<br />

ensure the existence of a community or the (co)existence<br />

of its members.<br />

The Venice Biennale is an institution that dates back<br />

to the turn of the previous century (1895). It launched the<br />

biennale movement that eventually spread throughout<br />

the world, picking up momentum in the early 1990s<br />

in tandem with the pace of globalization. This event,<br />

designed from its inception to be a great international<br />

gathering, took place at a period in history when the<br />

idea of the nation was being redefined and European<br />

countries, such as we know them today, were carving<br />

out their borders and forming their sense of identity. At<br />

a time when many new countries were forming or being<br />

reshaped through democratization and the affirmation<br />

of their identities, the Venice Biennale was an event that<br />

drew people from around the globe, and a place where<br />

everyone wanted to be. Today, the number of pavilions<br />

is still growing, a trend particularly characteristic of the<br />

first decade of this century, when contemporary art has<br />

secured a foothold on every continent.<br />

Israel’s participation in the Venice Biennale dates<br />

back to 1948, the year the country came into existence. Its<br />

pavilion, dating from 1955, was also the first non-European<br />

pavilion to be set up in the Giardini, the site set aside for<br />

the pavilions of various nations. The pavilion is a sign of<br />

the new country’s eagerness to participate in this great<br />

international forum. In the person of Zeev Rechter, Israel<br />

chose a modernist architect who ended up constructing<br />

a somewhat self-enclosed building that steered a path<br />

between the Bauhaus ethos, the legacy of Le Corbusier<br />

and Brutalism. Sigalit Landau has studied the history of<br />

this pavilion and discovered, as she perused the archives,<br />

that the Italians’ initial proposal called for a two-part<br />

structure. Here are some of the thoughts she had about it<br />

while developing the project:<br />

Take a close look at what the Italians suggested that we<br />

build, in the spirit of other pavilions: a pavilion with<br />

two centers, two spaces that flow well with the site<br />

of the Giardini and its paths, dialectic and figurative.<br />

The Israelis retaliated with a form even they had<br />

difficulties justifying... They made an introverted<br />

microcosm for themselves. […]fear of being camouflaged,<br />

fear of the joining of two voices. The pavilion is small with<br />

a super big defensive façade, a “WALL” and with a super<br />

complicated inside. 2<br />

The tone was set. The pavilion would become the site of a<br />

huge installation comprising several sequences evoking<br />

questions of territory and belonging, and especially<br />

the themes of connection and communication. Right<br />

from the start, the question of community was raised;<br />

in other words, that of the relationship with the Other<br />

and of the living together. Sigalit Landau immediately<br />

came up against this issue. She is also interested in<br />

Venice’s relationship to water. The city is, of course, built<br />

on water, shaped by an archipelago whose urban fabric<br />

retains the traces of its watery beginnings. Venice streets<br />

are, indeed, canals teeming with vaporetti, barges, boat<br />

taxis and gondolas. Pedestrians wander through stone<br />

corridors and cross countless bridges in the course of<br />

a day. In Israel, water supply is a major problem. In the<br />

latter half of the twentieth century, this formerly arid<br />

and desert-like land was transformed through irrigation.<br />

Vegetation was brought in from foreign countries and<br />

European-style houses were built.<br />

The Dead Sea and Water as the<br />

SubSTrate of AeSThetics<br />

Sigalit Landau is fascinated by the Dead Sea, which<br />

is threatened by both climate change and the direct<br />

intervention of human hands. This immense lake<br />

separates Israel, Jordan and the territories of the<br />

Palestinian Authority. Each year, the level of this watery<br />

expanse drops by a metre. At this rate, the Dead Sea is<br />

greatly endangered. This is an extraordinary natural<br />

phenomenon caused by the salt content of the water,<br />

which is 33% (compared with the ocean’s 2.5%). Few<br />

organisms can live in such a medium, which nonetheless<br />

contains large quantities of minerals such as magnesium<br />

and sodium chloride. These are much sought-after by<br />

industrial concerns whose operations have boosted the<br />

wealth of the countries in question. The ecological risks<br />

consequently entail major economic and geostrategic<br />

issues. Many solutions have been considered but to date<br />

nothing conclusive seems forthcoming. 3<br />

Sigalit’s works incorporate what can be called a<br />

reflection on the Dead Sea and on what it represents for<br />

humanity, and this apart from the major issues, what<br />

it suggests about human life and the perils facing it<br />

on both the personal and communal levels. This body<br />

of water, remarkable in so many ways (as a natural<br />

and economic resource, a tourist attraction, a site of<br />

political partition) is a space to be reinvented. Through<br />

her gaze and interventions, the real becomes a place of<br />

sensitive investment and transformation. She elaborates<br />

a different perspective on the issues in question, a<br />

difference affirmed by a logic that eschews the usual<br />

solutions.<br />

Her frequent use of watermelons, for example, is<br />

part of this developing thought process. In her video,<br />

Standing on a Watermelon in the Dead Sea (2005), she floats<br />

on the water using a melon as a raft. Her body remains<br />

thereby in a state of suspension that appears permanent,<br />

an effect produced by the fact that this is a video loop. The<br />

human body is made up mainly of water (sixty-five per<br />

cent), which also accounts for ninety per cent of our blood<br />

plasma. Standing on a Watermelon in the Dead Sea reminds us<br />

of the fact that the Dead Sea, with its high concentration<br />

of salt, enables the human body to float effortlessly, an<br />

effect that Sigalit Landau reinforces with the devices she<br />

uses. Nothing settles in this highly mineralized water.<br />

In a constant effort to keep the melon under her feet,<br />

the artist must perform a sort of sub-aquatic dance in<br />

which her body’s rhythms shift in harmony with the<br />

movement of the water. Keeping the melon balanced,<br />

she comes across as a sort of female Atlas, or Fortuna<br />

keeping the orb of sovereignty under her heel. The melon<br />

is reminiscent of female forms—it could be a belly or a<br />

head—and the image of this woman standing atop a<br />

water-borne sphere acts as a mirror image, an inverted<br />

reflection of the all-powerful male Atlas balancing the<br />

globe on his head. Here, the sea/mother is the bearer of<br />

female power, a power that is in constant motion and<br />

more in tune with the fluidity of the world than with its<br />

gravity.<br />

In another video, DeadSee (2005), Landau once again<br />

appears naked, floating on the surface of the salty water,<br />

surrounded by green melons that form a 250-metre spiral<br />

clearly discernible on the surface. Part of the spiral is<br />

composed of an agglomeration of disembowelled melons<br />

whose red pulp appears in a segment of the film, shot<br />

from above. The artist attempts to reach this part, to touch<br />

with her hand what appears, like herself, to be a mass of<br />

floating flesh—a gaping wound on the surface of this vast<br />

expanse of water where everything is slated to disappear.<br />

The spiral comes undone as the line binding the melons<br />

snakes beyond the frame of the image. Sigalit Landau<br />

disappears too. This work evokes another spiral that has<br />

left its imprint on art history, a spiral whose memory is<br />

preserved only on film when the work is submerged. I<br />

am speaking, of course, of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty<br />

(1970). Executed in Utah’s Great Salt Lake, this spiral made<br />

from basalt rocks is 450 metres long and four metres<br />

wide. The contrast with Sigalit’s ephemeral and organic<br />

sphere is striking. Here again, Sigalit Landau stands<br />

on the side of lightness and fluidity in the context of a<br />

metaphysical dialogue with the world, the environment<br />

and ecosystems. These artists’ respective visions of<br />

entropy affirm a difference that owes as much to their<br />

sexuality as it does to their geostrategic and intimate<br />

positioning. 4<br />

The watermelon keeps coming up again and again<br />

in Sigalit’s installations, including the one she made at<br />

Berlin’s Kunst-Werke in 2007. Entitled The Dining Hall,<br />

this piece took up the entire space and evoked a complex<br />

narrative that recalled the history of life in Israel,<br />

immigration, colonization, daily life and the mix of<br />

cultures, as well as the life somewhere between life and<br />

death, suffering and survival, that Giorgio Agamben calls<br />

“bare life.” 5 Hanging barbed wire lamps covered in salt<br />

crystals (Sigalit Landau had immersed their frames in<br />

water from the Dead Sea) hovered over the first segment<br />

of the installation, which called to mind a living room

170 171<br />

Space—Movement—Light<br />

Israeli Pavilion in Venice<br />

Matanya Sack<br />

The Israeli Pavilion in Venice is more of a lounge or<br />

salon for entertaining guests than a space for action.<br />

Sigalit Landau constantly examines the boundaries of<br />

the use of the pavilion’s space which was planned for<br />

receptions and for exhibiting pictures on walls and, from<br />

this aspect, she activates the space in a manner that<br />

is different from that which the architect or the state<br />

intended. Landau acts in the site, and creates through it<br />

complex associations between the specific place and the<br />

place that she represents and from which she comes.<br />

Israeli artists first participated in the Venice Art<br />

Biennale in 1948. Although back in 1946, despite objections<br />

from the British Mandate, a request was sent to the Mayor<br />

of Venice and chairman of the exhibition to authorize<br />

participation by artists from Eretz-Israel, an invitation for<br />

1947 arrived too late and Keren Hayesod could not prepare<br />

in time. Meanwhile, discussions began concerning<br />

the construction of a permanent pavilion that would<br />

represent Israel in the Biennale Gardens. The design of<br />

the pavilion was assigned to architect Zeev Rechter (1899-<br />

1960), at the end of 1951. Working on the project together<br />

with Zeev Rechter were architects Yaakov Rechter, Zeev’s<br />

son, and David Reznik who had just joined the firm (later<br />

each would be awarded the Israel Prize in Architecture).<br />

The construction was completed in 1955.<br />

Zeev Rechter, one of the founders of Israeli<br />

modernism, began his professional studies in the<br />

Ukraine and then immigrated to Eretz-Israel. Later, he<br />

completed his studies in Europe—initially in Rome (at<br />

the end of the 1920s) and later in Paris (at the beginning<br />

of the 1930s), but opened his studio in Eretz-Israel. In<br />

his work on the pavilion that was to represent Israel in<br />

the world, he exported back to Europe, the local Israeli<br />

language of modernism, as one of the forerunners of<br />

this language. Zeev Rechter never visited the site itself<br />

for budgetary reasons. The plans for the pavilion were<br />

delivered to a local contractor, who executed the work<br />

on his own, without the customary supervision of the<br />

architect. Rechter, who suddenly passed away in 1960,<br />

did not have the opportunity to visit the pavilion after<br />

its completion.<br />

Among plans and designs dating back to 1949 that<br />

were found in Zeev Rechter’s archive is a proposal by<br />

an Italian architect for the Israeli Pavilion. One sheet<br />

depicts the plan for the Giardini with the international<br />

pavilions, the proposed location for the Israeli Pavilion<br />

being right next to the American Pavilion, nearly in its<br />

shadow. The location provides prime exposure, being<br />

on the way to the New Area, and next to the canal that<br />

crosses the Biennale Gardens, through which important<br />

guests used to arrive on boats. On another sheet, the<br />

architect presents a detailed proposal for the pavilion<br />

in the shape of a structure divided into two exhibition<br />

areas, with an entry space between them. Both galleries,<br />

one a bit larger than the other, are designed in the shape<br />

of simple boxes with upper ribbon windows to let in the<br />

light. According to classical tradition, the entrance to a<br />

building is in the center, slightly elevated, and has a wide<br />

staircase. The entry space is also a passage, or crossing<br />

space, and at its other end is a smaller staircase leading<br />

to a secondary path in the garden. When Sigalit Landau<br />

saw the unrealized Italian proposal, she was enchanted<br />

by the dual narrative that seemed intrinsic to a divided<br />

space. The possibility of representing two contrasting<br />

opinions seemed to be dictated by the very division into<br />

two exhibition spaces; and the balance was imperfect,<br />

due to lack of symmetry between the two galleries.<br />

In 1951, a letter was sent on behalf of the President<br />

of the Arts Biennale to the Ministry of Education and<br />

Culture in Israel, stating that the architect could design<br />

the pavilion as he saw fit, but without deviating from<br />

the building lines. A blueprint indicating the building<br />

borders was attached to the letter. The letter also noted<br />

the need to respect the location of existing flowerbeds<br />

and trees. According to this design, the northern border<br />

of the pavilion was set by drawing a line from the corner<br />

of the American Pavilion to the bridge that crosses the<br />

Giardini canal. Rechter elevated the border lines into<br />

mass, thus emphasizing the presence of these lines in the<br />

geometry of the site and the movement of visitors within<br />

it. The pavilion’s northern entry façade is in line with the<br />

central path leading to it and creates a street-like wall,<br />

and, as such, integrates less with the free composition<br />

the garden might have enabled. The entrance is located<br />

at the northwestern corner in order to belong to and to<br />

point at the center of the exhibition.<br />

Inside the garden and across from the adjacent<br />

pavilions, some of which are constructed in neo-Classical<br />

style, the Israeli Pavilion shines in its modernist<br />

whiteness. Rechter, who was influenced by the works of<br />

the Swiss architect Le Corbusier, designed an architectural<br />

promenade on three levels on a small triangular plot of<br />

250 square meters. Two staircases connect the levels,<br />

enabling a circular, non-repetitive route through all the<br />

spaces. Rechter’s focus is on space—movement—light. In<br />

all the sketches and designs, circulation appears central,<br />

guiding the construction of the space. From remaining<br />

documents of the design process, we can clearly see<br />

the search for downward and upward movement, in<br />

the middle (there is an intermediate level), and in all<br />

directions (two separate staircases). The challenge that<br />

Rechter set himself was to create several levels in a small<br />

space, with height limitations (the pavilion’s height is in<br />

line with the height of the adjacent American Pavilion).<br />

While most of the other pavilions are on a single level,<br />

Rechter connects the three internal levels; a courtyard,<br />

which, as it encounters the interior, unites with the<br />

same circulation system, was planned by a local architect<br />

and added in the 1960s. The movement of people in the<br />

pavilion’s space is as dominant and attention-attracting<br />

as the exhibits themselves.<br />

The shape of the pavilion’s design becomes clear<br />

when one moves around it, and on the top floor the space<br />

becomes comprehensible. This impression stems from<br />

the multiplicity of options for movement and half-floors.<br />

Here it is only natural to refer to the Helena Rubinstein<br />

Pavilion for Contemporary Art in Tel Aviv that Zeev<br />

Rechter designed in the late 50s (in collaboration with<br />

architect Dov Karmi and architect Yaakov Rechter).<br />

There, too, Rechter used levels at half-height suspended<br />

on a wide staircase and created a unique space whereby<br />

the views are long and deep and take in several levels<br />

simultaneously. Sigalit Landau examined Rechter’s space<br />

in the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion while working on her<br />

2005 large solo exhibition entitled The Endless Solution. In<br />

the Venice Pavilion, Landau conforms to the power of the<br />

movement system that dictates the experience within<br />

the space, yet she disrupts its hierarchy. Landau built a<br />

route so that from the lower level one walks up a spiral<br />

staircase to the upper level, and from there descends to<br />

the intermediate level, continuing down a side staircase<br />

to the courtyard, from which one exits back to the garden.<br />

The route is no longer circular, and visitors no longer exit<br />

at the point where entered. Landau does not invite one to<br />

visit the pavilion, but rather to take a journey through it.<br />

The original glass entry façade was situated deep<br />

inside the space, serving as a covered entrance lobby<br />

to the exhibition space. During one of the pavilion’s<br />

renovations, the glass doors were moved outwards, close<br />

to one meter from the facade. This act enlarged the space<br />

but dissipated the construction concept. This is especially<br />

notable when one is inside the space looking out: it is hard<br />

not to wonder about the location and meeting point of the<br />

glass walls. Landau activates this space with precision<br />

and leads the visitors through the gap created between<br />

the later external wall and the earlier modernistic<br />

line which is only slightly disconnected from the<br />

construction. The passage from the outside to the inside<br />

seems to stretch and the experience of space changes.<br />

Throughout the year, when there are no exhibitions,<br />

the pavilions in the Biennale Gardens are sealed. Landau<br />

preserved this sealing and extended it to the exhibition<br />

period and in fact darkens the pavilion. The glass walls<br />

are covered, creating an entry corridor that leads from the<br />

illuminated exterior to the dark interior space. The large<br />

south-facing wall-window which is the main source of<br />

light of the pavilion was also sealed. In the original plan,<br />

the wall-window was the only connection to the garden<br />

in the back of the building with its wild vegetation.<br />

The pavilion’s ceiling, which is usually perforated with<br />

skylights, was sealed by Landau, using black acoustic<br />

plaster. The new ceiling traces the openings, rises and<br />

descends back to create a wavy ceiling. From an abstract<br />

source of light, the ceiling is transformed into a new<br />

object. The darkening of the pavilion is linked to the<br />

blurring of scale and an apparent attempt to deal with<br />

the limited size of the pavilion, and helps the visitor to<br />

perceive it as he or she looks across the space.<br />

When exhibiting at the Venice Biennale, Landau<br />

refers to the pavilion as a site, and not as a space for the<br />

exhibition of her art works. Her passion is to change the<br />

national pavilion, to create a more complex story than<br />

that which it is supposed to enable as a wall surface for<br />

art exhibitions. In one of the preparatory stages of her<br />

work, she attempted to dig a lower level in the pavilion,<br />

but this action was stopped by the Properties Department<br />

of the Foreign Affairs Ministry that refused to approve<br />

structural changes.

178 179<br />

Ensemble<br />

Jean de Loisy<br />

L’injonction faite par Robert Smithson, souhaitant que<br />

chaque artiste « explore l’esprit pré et post-historique » et<br />

qu’il aille « là où les futurs lointains rencontrent les passés<br />

lointains »* correspond exactement au sens du séjour obstiné<br />

de Sigalit Landau sur les rives de la mer Morte. Elle travaille<br />

là depuis des années, au point le plus bas du monde, dans ce<br />

paysage désolé, accablé par le soufre et le feu envoyé par le<br />

Dieu de la Bible, blessé par l’histoire, meurtri par un désastre<br />

écologique en cours, théâtre brûlant sur lequel pèsent encore<br />

de nombreux conflits régionaux. Chaque mouvement sous ce<br />

soleil impitoyable coûte, et les gestes accomplis doivent être<br />

économes. Il faut qu’ils aient l’efficacité et le sens suffisant<br />

pour justifier la fatigue qu’ils génèrent. Comme pour ces<br />

efforts soigneusement anticipés, une extrême condensation<br />

caractérise chacune des réalisations de cette artiste. Une image,<br />

un plan, un objet transformé, suffisent souvent à véhiculer un<br />

feuilleté de significations ou à fixer une métaphore qui résonne<br />

immédiatement dans nos esprits. Par exemple, un filet plongé<br />

dans cette mer stérile, puis retiré, couvert de cristaux de sel, ou<br />

encore, un fil de fer barbelé qui tourne sur un ventre de femme,<br />

le sien, pour citer une sculpture récente et une vidéo ancienne<br />

devenue une icône collective. Ces deux œuvres réalisées à dix<br />

ans d’écart portent une symbolique universelle dont la force est<br />

à la mesure des sites où ces images se sont formées. Pas de<br />

bavardage, pas de psychologie, pas de narcissisme de créateur,<br />

une grâce silencieuse, un pouvoir. Ce sont des objets puissants<br />

qui agissent sur l’esprit comme des déclencheurs. Certes ils<br />

s’adressent à notre conscience, ils soulèvent des questions<br />

essentielles, mais aucune morale, aucune démonstration. Seul<br />

opère sur nous l’impact prémédité de leur présence laconique.<br />

Sigalit Landau répond en poète aux alertes de l’époque,<br />

comme purent le faire à leur manière des artistes aussi différents<br />

que Goya ou Beuys. Mais, quant à elle, ce n’est ni en mettant en<br />

* Robert Smithson, “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects.”<br />

Artforum, September 1968<br />

évidence le spectacle tragique de la désolation ou de la barbarie,<br />

ni en agissant politiquement en créant le parti des étudiants<br />

pour changer la société. Non, plutôt la simple amplification<br />

des sonorités de la réalité ou des situations. L’autre, l’eau, le<br />

travail, la communauté ou le partage des ressources… Ainsi,<br />

tout en s’appuyant sur ces grands sujets Sigalit Landau parvient<br />

à réduire la distance que l’actualité continuelle produit en les<br />

rabâchant. Ces questions rendues abstraites par l’insistance<br />

des médias, retrouvent un lien avec nos expériences les plus<br />

quotidiennes : porter, cueillir, pêcher, nager, jouer, habiter, se<br />

souvenir. Exprimées avec simplicité dans ses films, souvent faits<br />

d’un plan fixe, sans montage apparent, ou par ses sculptures<br />

figuratives, elles nous atteignent à nouveau par l’évidence grave<br />

qu’elles expriment. En effet, en elles, en dépit des expressions<br />

si nouvelles ou des techniques, s’est glissée une temporalité,<br />

une mémoire que ne parvient pas à contredire la modernité<br />

éventuelle du contexte ou des supports. Par exemple, la spirale<br />

de melons d’eau qui se déroule, flottant sur la mer Morte, semble<br />

nous relier à des temps anciens où d’autres blessures pouvaient<br />

comme aujourd’hui ouvrir la chair rouge de la vie. Il en va de<br />

même pour la sueur de bronze des corps mêlés qui poussent<br />

un même rocher pour trouver de l’eau, ou encore pour les<br />

masques de sucre rose que l’artiste confectionne pour le public<br />

en 2001. Parfois ce sont les sujets, parfois les matériaux, parfois<br />

les figures qui créent ce lien avec l’origine de l’art, le masque,<br />

le bronze et, surtout, le rituel, ce comportement organisé des<br />

corps dans l’espace et le temps, dont l’art de la performance est<br />

encore imprégné et qui semble, en permanence affleurer dans<br />

ces œuvres, leur donnant cette puissante profondeur.<br />

Venise : One Man’s Floor is Another Man’s Feelings. Cette fois-ci,<br />

le titre est un programme esthétique et politique. D’abord<br />

griffonné sur une nappe de restaurant, il apparaît comme la<br />

trace, le condensé peut-être d’une conversation à laquelle nous<br />

n’avons pas participé. En transparence, se devinent, fruits d’une<br />

discussion antérieure, d’autres mots à peine distincts. Une

180 181<br />

porosité, une rumeur est donc perceptible entre le dessus et<br />

le dessous. La séparation ne divise pas, un échange chimique<br />

entre l’encre, l’appuyé du stylo et la faiblesse du papier a eu<br />

lieu, l’envers rejoint dans le visible l’existence de l’endroit, et les<br />

deux faces s’enrichissent de cette perturbation. Apparaissent<br />

déjà dans l’esthétique de ce simple papier des caractéristiques<br />

générales de l’œuvre et également du projet. En effet, très<br />

souvent le travail de Sigalit Landau insiste sur le lien qui réunit<br />

deux personnes ou un groupe ou des voisins. Cette idée de la<br />

communauté et de l’inséparation est fondatrice de ce pavillon<br />

imaginé comme une seule œuvre. On se souvient du film<br />

Dancing for Maya en 2005 où les corps des deux protagonistes<br />

se rejoignent en traçant sur le sable une ligne courbe qui mêlée<br />

dessine une chaîne, un ADN commun. Ou encore de cette<br />

situation qu’elle inventa oÙ le visiteur amenait une clef (The<br />

Dining Hall, 2007, Berlin) qui était immédiatement dupliquée à<br />

l’envers. Celui-ci repartait ainsi avec la clef d’un voisin plausible<br />

auquel il pouvait maintenant penser puisqu’une ligne commune<br />

bien qu’inverse les reliait désormais. De même, les corps des<br />

trois hommes se déhanchant dans la vidéo Three Men Hula qui<br />

doivent harmoniser leur mouvement pour parvenir à balancer<br />

le cercle qui les unit. Les exemples seraient nombreux et<br />

aboutiraient tous à cette déclaration : One Man’s Floor is Another<br />

Man’s Feelings, devenue le titre du projet du pavillon vénitien.<br />

Préparant ce grand poème pour le pavillon, Sigalit Landau<br />

mimait souvent les déplacements du visiteur. Bougeant dans<br />

l’atelier, les yeux presque clos, on la devinait pénétrer dans la<br />

première salle, esquisser un recul, tourner à droite puis à gauche<br />

pour éviter un obstacle encore invisible, puis se baisser comme<br />

pour mieux voir et lever la tête pour suivre du regard un mur<br />

plus haut, etc. Ainsi la trajectoire des visiteurs a été préparée,<br />

chorégraphiée par l’artiste pour dérouler le fil de l’histoire<br />

qu’elle nous propose. Comme les enchaînements d’une danse,<br />

aucun moment ne peut être délié des autres et c’est donc bien<br />

dans la continuité temporelle et physique de la visite que se<br />

révèlent les significations que construisent les trois temps de<br />

ce parcours qui s’adresse à nos corps autant qu’à notre esprit.<br />

Les tuyaux qui encombrent la première salle surgissent<br />

d’un point obscur du pavillon. Un trou de terre meuble dans<br />

laquelle ils s’enracinent et d’où ils pompent sans cesse. L’œuvre<br />

s’origine dans cette caverne qui devient le cœur battant<br />

de tout le projet, et qui évoque aussi les périodes les plus<br />

anciennes de l’art. Dans la chambre des machines, on perçoit<br />

le bruit des pompes et de l’eau qui court dans les canalisations<br />

en affolant les innombrables compteurs qui égrènent les<br />

quantités précieuses. L’eau est enfermée dans ces éléments<br />

massifs comme retenue dans le creux des mains. Puis le<br />

regardeur quitte cette situation originelle et se confronte aux<br />

circonstances du présent. Le filet qui cueillait la vie nécessaire à<br />

la communauté ne recueille plus que le sel infertile. A côté, une<br />

vidéo montre le processus lent de la transformation possible.<br />

Une image presque fixe des chaussures, symboles de notre<br />

présence au monde. Préalablement immergées dans la mer<br />

Morte, couvertes de cristaux, elles ont ensuite été déposées<br />

à la surface d’un lac gelé à Gdansk, devant cette ville qui sut<br />

changer l’histoire de la fin du vingtième siècle. Les propriétés<br />

naturelles et contradictoires du sel et de la glace dissolvent<br />

celle-ci et les souliers s’enfoncent peu à peu sous nos yeux.<br />

L’artiste nous confronte par cette puissante vision au sablier de<br />

notre espérance : faire de ce sel, c’est-à-dire de l’amertume du<br />

présent, le solvant qui peut nous réunir.<br />

Penché par-dessus le parapet de l’étage, le visiteur<br />

assiste à une discussion. Les voix, les accents, les langues se<br />

mêlent. Ce sont des extraits des négociations effectivement<br />

commencées avec des acteurs économiques et politiques<br />

régionaux. L’avenir commence là, dans ce troisième temps<br />

du pavillon oÙ ceux qui devront un jour devenir partenaires<br />

débattent déjà de la proposition faite par Sigalit Landau, il y<br />

a moins d’un an, d’engager un projet poétique et politique : la<br />

nécessité de construire un pont qui relie Israël et la Jordanie<br />

sur la mer Morte. Peu importe cette géographie, la situation<br />

peut être transposée ailleurs. Sous la table, l’enfant inaperçue<br />

relie les chaussures des négociateurs. Savent-ils qu’au futur,<br />

qui est le temps de cette salle et de cette fille espiègle, ils sont<br />

liés ? Et le visiteur retrouvant la lumière des jardins, ayant fait<br />

le voyage que l’artiste, tous les artistes, effectuent dans leurs<br />

œuvres quand elles sont essentielles, de l’humanité des origines<br />

aux circonstances du présent à la transformation du futur, le<br />

visiteur donc sort alors devant ce non-monument, dédié aux<br />

hommes capables de chausser les souliers lacés entre-eux, les<br />

responsables de l’avenir qui sauront marcher ensemble.<br />

Le Point de Gel et de Fusion<br />

Ilan Wizgan<br />

Le pavillon israélien dans les jardins de la Biennale de Venise,<br />

avec son histoire, sa géographie et sa morphologie, constitue le<br />

point de départ du projet de Sigalit Landau. Le pavillon, imaginé<br />

à la fin des années quarante, a été conçu par l’architecte<br />

israélien Zeev Rechter et inauguré vers le milieu des années<br />

cinquante. Les autorités de Venise ont alloué à ce dernier un<br />

site près du pavillon américain, au bord du canal des Giardini.<br />

Parmi la variété des styles architecturaux caractérisant les<br />

pavillons nationaux dans les jardins de la Biennale, entre les<br />

pavillons néo-gothiques et néo-classiques, Rechter a choisi<br />

de concevoir un pavillon de style moderniste, dans l’esprit du<br />

Bauhaus et du Style international qui caractérisait l’architecture<br />

en Israël avant l’établissement de l’Etat.<br />

Le pavillon a été conçu sous la forme d’une villa sur trois<br />

niveaux, avec une façade large et inaccessible, sans fenêtre, qui<br />

semble tourner le dos à la route d’accès et aux autres pavillons.<br />

A l’arrière de celui-ci une énorme fenêtre et une cour agréable<br />

et accueillante ont été installées, entourées et cachées par des<br />

arbres. L’emplacement, la forme et la vision du monde inhérente<br />

à sa conception font écho à la conscience collective israélienne<br />

et à la situation géopolitique de l’Etat d’Israël (la contiguïté du<br />

pavillon américain, la proximité de la mer, le pavillon égyptien<br />

de l’autre côté du canal…). Sigalit Landau a pris en compte tous<br />

ces facteurs pour concevoir sa proposition. En outre, la période<br />

historique qu’est celle de la conception et de la construction du<br />

pavillon - période pendant laquelle la nation israélienne s’est<br />

formée d’un point de vue politique, démographique, ethnique,<br />

social et architectural - coïncide avec celle à laquelle Sigalit<br />

Landau se réfère dans ses travaux récents. *<br />

Dans le cadre de ses enquêtes préparatoires, l’artiste a en<br />

effet vérifié les circonstances de la création du pavillon. Elle a<br />

effectué des recherches dans les archives de l’architecte, et a<br />

exhumé le moindre vieux document jauni pouvant lui apporter<br />

* Pour de plus amples détails sur l’histoire du pavillon et de sa<br />

conception, veuillez consulter l’article de Matanya Sack page 193.<br />

des informations sur le processus, de l’idée de départ (avant<br />

la création de l’Etat d’Israël) jusqu’au plan achevé. La décision<br />

de l’artiste est alors de s’opposer, de défier le concept de cette<br />

architecture, ignorante des besoins en matière d’exposition des<br />

œuvres d’art, privilégiant la lumière instable du sud à la lumière<br />

du nord, présentant un plafond trop bas au niveau de l’entrée,<br />

un niveau supérieur « flottant » avec seulement deux murs, et<br />

des escaliers en colimaçon dans l’espace. Comme d’habitude,<br />

Sigalit Landau ne tient pas compte du bâtiment comme d’une<br />

chose qui va de soi et qu’il faudrait absolument respecter. Elle<br />

est persuadée que l’espace doit servir le travail et non l’inverse.<br />

L’espace concret est en effet toujours le point de départ. C’est<br />

lui qui engendre le travail. Cependant une fois les décisions<br />

principales entérinées et la structure planifiée, le travail<br />

entraine et « requiert » des ajustements, des changements dans<br />

le bâtiment comme la destruction de murs, l’occultation de<br />

fenêtres, l’ouverture de trous béants, des fouilles, etc.<br />

L’étage inférieur<br />

En entrant dans l’exposition, le visiteur se trouve dans un<br />

espace ressemblant à une salle des machines. A une extrémité,<br />

entre les deux cages d’escaliers, une vidéo est projetée sur le sol.<br />

Il s’agit d’un groupe d’hommes qui jouent au « Jeu des Pays »:<br />

ils tracent un rectangle imaginaire dans le sable, lancent des<br />

couteaux à l’intérieur et se partagent le territoire. L’espace<br />

est envahi par un vaste système de compteurs d’eau et de<br />

tuyaux sortant les uns des autres, montant et descendant,<br />