5-paragraph essay

5-paragraph essay

5-paragraph essay

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

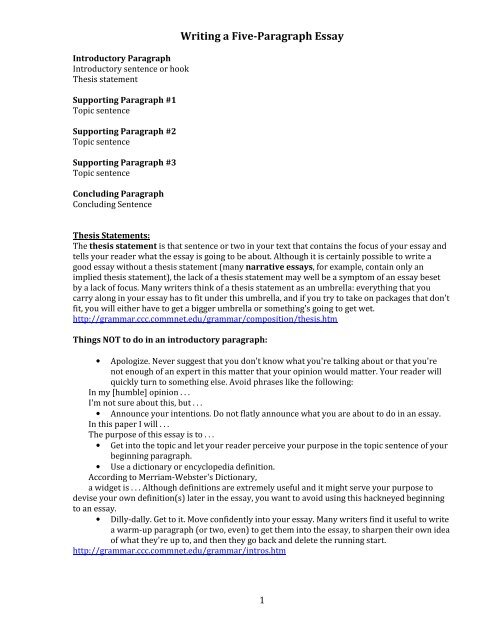

Introductory Paragraph<br />

Introductory sentence or hook<br />

Thesis statement<br />

Supporting Paragraph #1<br />

Topic sentence<br />

Supporting Paragraph #2<br />

Topic sentence<br />

Supporting Paragraph #3<br />

Topic sentence<br />

Concluding Paragraph<br />

Concluding Sentence<br />

Writing a Five-Paragraph Essay<br />

Thesis Statements:<br />

The thesis statement is that sentence or two in your text that contains the focus of your <strong>essay</strong> and<br />

tells your reader what the <strong>essay</strong> is going to be about. Although it is certainly possible to write a<br />

good <strong>essay</strong> without a thesis statement (many narrative <strong>essay</strong>s, for example, contain only an<br />

implied thesis statement), the lack of a thesis statement may well be a symptom of an <strong>essay</strong> beset<br />

by a lack of focus. Many writers think of a thesis statement as an umbrella: everything that you<br />

carry along in your <strong>essay</strong> has to fit under this umbrella, and if you try to take on packages that don't<br />

fit, you will either have to get a bigger umbrella or something's going to get wet.<br />

http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/composition/thesis.htm<br />

Things NOT to do in an introductory <strong>paragraph</strong>:<br />

• Apologize. Never suggest that you don't know what you're talking about or that you're<br />

not enough of an expert in this matter that your opinion would matter. Your reader will<br />

quickly turn to something else. Avoid phrases like the following:<br />

In my [humble] opinion . . .<br />

I'm not sure about this, but . . .<br />

• Announce your intentions. Do not flatly announce what you are about to do in an <strong>essay</strong>.<br />

In this paper I will . . .<br />

The purpose of this <strong>essay</strong> is to . . .<br />

• Get into the topic and let your reader perceive your purpose in the topic sentence of your<br />

beginning <strong>paragraph</strong>.<br />

• Use a dictionary or encyclopedia definition.<br />

According to Merriam-Webster's Dictionary,<br />

a widget is . . . Although definitions are extremely useful and it might serve your purpose to<br />

devise your own definition(s) later in the <strong>essay</strong>, you want to avoid using this hackneyed beginning<br />

to an <strong>essay</strong>.<br />

• Dilly-dally. Get to it. Move confidently into your <strong>essay</strong>. Many writers find it useful to write<br />

a warm-up <strong>paragraph</strong> (or two, even) to get them into the <strong>essay</strong>, to sharpen their own idea<br />

of what they're up to, and then they go back and delete the running start.<br />

http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/intros.htm<br />

1

Writing Strong Body/Supporting Paragraphs:<br />

How do writers support their thesis statements? How do they organize their evidence? How do they<br />

know when to change <strong>paragraph</strong>s, and what information should go into which <strong>paragraph</strong>? This is<br />

where the phrase AXES can help.<br />

AXES stands for a series of tasks (not necessarily “just a sentence” each), that all strong body<br />

<strong>paragraph</strong>s possess.<br />

A<br />

X<br />

E<br />

S<br />

Assertion<br />

Example<br />

Explanation<br />

Significance<br />

Assertion<br />

Make a Claim about your Topic<br />

An assertion is another word for “claim,” and it is often called a topic sentence. Yet, for many<br />

students, the phrase “topic sentence” can be confusing, as the term topic sentence is often confused<br />

with simply announcing the topic. However, just as a good thesis statement reveals your overall<br />

stance in the <strong>essay</strong>, a good assertion (topic sentence) will reveal your overall stance on the<br />

<strong>paragraph</strong>’s topic. Using the word Assertion instead of topic sentence can help remind you that a<br />

good lead sentence will make a claim about the topic, not just an announcement.<br />

EXample<br />

Prove Your Claim<br />

Whenever a claim is made, evidence or proof is required to support that claim. Example, the X of<br />

AXES, is that proof. Your example(s) could be in the form of textual evidence, quotations, facts,<br />

statistics, percentages, scenarios, or anecdotes, but the goal of the example is to support or “back<br />

up” your assertion. This is your “proof” section of the <strong>paragraph</strong>.<br />

Explanation<br />

Explain your Proof<br />

A good Explanation connects your example(s) to your assertion, demonstrating WHY your<br />

examples make your assertion true. For this reason, it is one of the most important aspects of a<br />

strong body <strong>paragraph</strong>. Although you might think your examples “obviously” prove you assertions<br />

to be true, this is not always the case. Think of the explanation as the sentence or sentences that<br />

“spell” out for the reader why your examples make your assertion valid.<br />

Significance<br />

So What?: Connect your Paragraph to your Thesis<br />

Significance is another word for importance, or “consequence” and this is exactly what this portion<br />

of a good/strong body <strong>paragraph</strong> tells its readers. Every <strong>paragraph</strong> should include a statement that<br />

relates why your assertion is important, why it matters. Significance will tell the reader how your<br />

assertion connects to your paper’s overall thesis, or to tell the real-life consequences of the topic.<br />

Concluding Paragraph:<br />

Your conclusion is your opportunity to wrap up your <strong>essay</strong> in a tidy package and bring it home for<br />

your reader. It is a good idea to recapitulate what you said in your Thesis Statement in order to<br />

suggest to your reader that you have accomplished what you set out to accomplish. It is also<br />

important to judge for yourself that you have, in fact, done so. If you find that your thesis statement<br />

now sounds hollow or irrelevant — that you haven't done what you set out to do — then you need<br />

either to revise your argument or to redefine your thesis statement. Don't worry about that; it<br />

happens to writers all the time. They have argued themselves into a position that they might not<br />

have thought of when they began their writing. Writing, just as much as reading, is a process of self<br />

discovery. Do not, in any case, simply restate your thesis statement in your final <strong>paragraph</strong>, as<br />

that would be redundant. Having read your <strong>essay</strong>, we should understand this main thought with<br />

fresh and deeper understanding, and your conclusion wants to reflect what we have learned.<br />

2

There are some cautions we want to keep in mind as we fashion our final utterance. First, we don't<br />

want to finish with a sentimental flourish that shows we're trying to do too much. It's probably<br />

enough that our <strong>essay</strong> on recycling will slow the growth of the landfill in Hartford's North<br />

Meadows. We don't need to claim that recycling our soda bottles is going to save the world for our<br />

children's children. (That may be true, in fact, but it's better to claim too little than too much;<br />

otherwise, our readers are going to be left with that feeling of "Who's he/she kidding?") The<br />

conclusion should contain a definite, positive statement or call to action, but that statement needs<br />

to be based on what we have provided in the <strong>essay</strong>.<br />

Second, the conclusion is no place to bring up new ideas. If a brilliant idea tries to sneak into our<br />

final <strong>paragraph</strong>, we must pluck it out and let it have its own <strong>paragraph</strong> earlier in the <strong>essay</strong>. If it<br />

doesn't fit the structure or argument of the <strong>essay</strong>, we will leave it out altogether and let it have its<br />

own <strong>essay</strong> later on. The last thing we want in our conclusion is an excuse for our readers' minds<br />

wandering off into some new field. Allowing a peer editor or friend to reread our <strong>essay</strong> before we<br />

hand it in is one way to check this impulse before it ruins our good intentions and hard work.<br />

Never apologize for or otherwise undercut the argument you've made or leave your readers with<br />

the sense that "this is just little ol' me talking." Leave your readers with the sense that they've been<br />

in the company of someone who knows what he or she is doing. Also, if you promised in the<br />

introduction that you were going to cover four points and you covered only two (because you<br />

couldn't find enough information or you took too long with the first two or you got tired), don't try<br />

to cram those last two points into your final <strong>paragraph</strong>. The "rush job" will be all too apparent.<br />

Instead, revise your introduction or take the time to do justice to these other points.<br />

Here is a brief list of things that you might accomplish in your concluding <strong>paragraph</strong>(s).* There are<br />

certainly other things that you can do, and you certainly don't want to do all these things. They're<br />

only suggestions:<br />

• include a brief summary of the paper's main points.<br />

• ask a provocative question.<br />

• use a quotation.<br />

• evoke a vivid image.<br />

• call for some sort of action.<br />

• end with a warning.<br />

• universalize (compare to other situations).<br />

• suggest results or consequences.<br />

http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/composition/endings.htm<br />

3