Why Off-the-Shelf RDBMSs are Better at XPath ... - ACM Digital Library

Why Off-the-Shelf RDBMSs are Better at XPath ... - ACM Digital Library

Why Off-the-Shelf RDBMSs are Better at XPath ... - ACM Digital Library

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ABSTRACT<br />

<strong>Why</strong> <strong>Off</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-<strong>Shelf</strong> <strong>RDBMSs</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>Better</strong> <strong>at</strong> XP<strong>at</strong>h<br />

Than You Might Expect<br />

Torsten Grust Jan Rittinger Jens Teubner<br />

To compens<strong>at</strong>e for <strong>the</strong> inherent impedance mism<strong>at</strong>ch between<br />

<strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional d<strong>at</strong>a model (tables of tuples) and XML<br />

(ordered, unranked trees), tree join algorithms have become<br />

<strong>the</strong> prevalent means to process XML d<strong>at</strong>a in rel<strong>at</strong>ional d<strong>at</strong>abases,<br />

most notably <strong>the</strong> TwigStack [6], structural join [1],<br />

and staircase join [13] algorithms. However, <strong>the</strong> addition of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se algorithms to existing systems depends on a significant<br />

invasion of <strong>the</strong> underlying d<strong>at</strong>abase kernel, an option<br />

intolerable for most d<strong>at</strong>abase vendors.<br />

Here, we demonstr<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> we can achieve comparable<br />

XP<strong>at</strong>h performance without touching <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> system.<br />

We c<strong>are</strong>fully exploit existing d<strong>at</strong>abase functionality<br />

and acceler<strong>at</strong>e XP<strong>at</strong>h navig<strong>at</strong>ion by purely rel<strong>at</strong>ional means:<br />

partitioned B-trees bring access costs to secondary storage to<br />

a minimum, while aggreg<strong>at</strong>ion functions avoid an expensive<br />

comput<strong>at</strong>ion and removal of duplic<strong>at</strong>e result nodes to comply<br />

with <strong>the</strong> XP<strong>at</strong>h semantics. Experiments carried out on<br />

IBM DB2 confirm th<strong>at</strong> our approach can turn off-<strong>the</strong>-shelf<br />

d<strong>at</strong>abase systems into efficient XP<strong>at</strong>h processors.<br />

C<strong>at</strong>egories and Subject Descriptors<br />

H.2.4 [Inform<strong>at</strong>ion Systems]: D<strong>at</strong>abase Management—<br />

Systems; H.3.4 [Inform<strong>at</strong>ion Systems]: Inform<strong>at</strong>ion Storage<br />

and Retrieval—Systems and Softw<strong>are</strong><br />

General Terms<br />

Performance, Experiment<strong>at</strong>ion, Languages<br />

Keywords<br />

XP<strong>at</strong>h, SQL, Partitioned B-Tree, Rel<strong>at</strong>ional D<strong>at</strong>abases<br />

1. INTRODUCTION<br />

The use of suitable tree encodings can turn rel<strong>at</strong>ional d<strong>at</strong>abase<br />

back-ends into highly efficient XP<strong>at</strong>h processors, an<br />

XML storage approach th<strong>at</strong> has since become widely accepted<br />

in research and industry. With efficient RDBMS<br />

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for<br />

personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided th<strong>at</strong> copies <strong>are</strong><br />

not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and th<strong>at</strong> copies<br />

bear this notice and <strong>the</strong> full cit<strong>at</strong>ion on <strong>the</strong> first page. To copy o<strong>the</strong>rwise, to<br />

republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific<br />

permission and/or a fee.<br />

SIGMOD’07, June 12–14, 2007, Beijing, China.<br />

Copyright 2007 <strong>ACM</strong> 978-1-59593-686-8/07/0006 ...$5.00.<br />

Technische Universität München<br />

Munich, Germany<br />

torsten.grust | jan.rittinger | jens.teubner@in.tum.de<br />

949<br />

implement<strong>at</strong>ions in <strong>the</strong> back, rel<strong>at</strong>ional XQuery implement<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

excel with a scalability to multi-gigabyte XML instances<br />

(e.g., [5, 17]).<br />

To compens<strong>at</strong>e for <strong>the</strong> lack of tree-aw<strong>are</strong>ness in rel<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

systems, various algorithms have been established to process<br />

encoded XML tree instances, most notably <strong>the</strong> TwigStack<br />

[6], structural join [1], multi-predic<strong>at</strong>e merge join [24], and<br />

staircase join [13] algorithms. But although c<strong>are</strong> has been<br />

taken to limit <strong>the</strong> required change impact to a single d<strong>at</strong>abase<br />

oper<strong>at</strong>or, all of <strong>the</strong>se proposals depend on modific<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

to <strong>the</strong> internals of <strong>the</strong> underlying RDBMS kernel, a requirement<br />

th<strong>at</strong> may be unacceptable in actual systems (e.g., if<br />

<strong>the</strong> RDBMS does not allow kernel modific<strong>at</strong>ions).<br />

In this paper, we demonstr<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> existing and commonly<br />

available d<strong>at</strong>abase techniques can make up for a large<br />

part of this limit<strong>at</strong>ion. We deliber<strong>at</strong>ely use an off-<strong>the</strong>-shelf<br />

RDBMS implement<strong>at</strong>ion for <strong>the</strong> task of evalu<strong>at</strong>ing XP<strong>at</strong>h<br />

loc<strong>at</strong>ion steps (IBM DB2 for th<strong>at</strong> m<strong>at</strong>ter). A closer look<br />

<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> indexing and execution techniques th<strong>at</strong> this system<br />

uses reveals interesting insights into why rel<strong>at</strong>ional systems<br />

perform so well <strong>at</strong> XP<strong>at</strong>h. Three common techniques from<br />

<strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional domain proved particularly effective for XML<br />

tree processing:<br />

(i) The use of partitioned B-trees, a technique recently described<br />

by Graefe [9] significantly speeds up <strong>the</strong> evalu<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of non-recursive XP<strong>at</strong>h axes (child, p<strong>are</strong>nt) and<br />

XP<strong>at</strong>h node tests (name and/or kind tests). The same<br />

idea can implement TwigStack’s node streams [6] or<br />

simul<strong>at</strong>e schema-based encoding techniques [20, 22] in<br />

a seamless fashion.<br />

(ii) Aggreg<strong>at</strong>ion functions provide a purely rel<strong>at</strong>ional implement<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of <strong>the</strong> pruning idea, a key aspect in <strong>the</strong><br />

aforementioned tree join algorithms.<br />

(iii) By purely rel<strong>at</strong>ional means, RDBMS query optimizers<br />

embrace rewriting techniques for queries over treestructured<br />

d<strong>at</strong>a th<strong>at</strong> required tailor-made XML support<br />

in earlier work.<br />

We will motiv<strong>at</strong>e all <strong>the</strong>se techniques with experiments<br />

carried out in IBM DB2 (using its SQL functionalities only)<br />

and closely look <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> query plans employed by this system.<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> tree encodings proposed in <strong>the</strong> liter<strong>at</strong>ure,<br />

we chose <strong>the</strong> pre/size/level range encoding to perform<br />

<strong>the</strong>se experiments. The effects we describe, however, apply<br />

equally well to o<strong>the</strong>r node-based numbering schemes,<br />

including those based on pre/post [10] or Dewey numbers<br />

[23].

We will proceed as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews rel<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

XML tree encodings, <strong>the</strong> range encoding (pre/size/<br />

level) in particular. Based on this encoding, we demonstr<strong>at</strong>e<br />

<strong>the</strong> use of partitioned B-trees to acceler<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of<br />

XP<strong>at</strong>h’s child and p<strong>are</strong>nt axes as well as XP<strong>at</strong>h node tests<br />

(Section 3). In Section 4, we realize staircase join’s pruning<br />

idea [13] on an SQL-only system, before we exploit fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

RDBMS facilities for efficient XP<strong>at</strong>h processing in Section 5.<br />

We comp<strong>are</strong> our results with rel<strong>at</strong>ed work in Section 6 and<br />

wrap up in Section 7.<br />

2. RELATIONAL TREE ENCODINGS<br />

Any rel<strong>at</strong>ional XQuery implement<strong>at</strong>ion th<strong>at</strong> strives for<br />

compliance with <strong>the</strong> W3C specific<strong>at</strong>ions [4] is bound to represent<br />

XML document trees in a schema-oblivious fashion.<br />

Acceptable support for <strong>the</strong> recursion inherent to XML d<strong>at</strong>a<br />

is provided by Dewey-based encodings (e.g., [18, 23]) and encodings<br />

th<strong>at</strong> use pre- and postorder ranks to describe node<br />

rel<strong>at</strong>ionships in terms of region conditions (e.g., [5, 7, 10,<br />

15, 24]).<br />

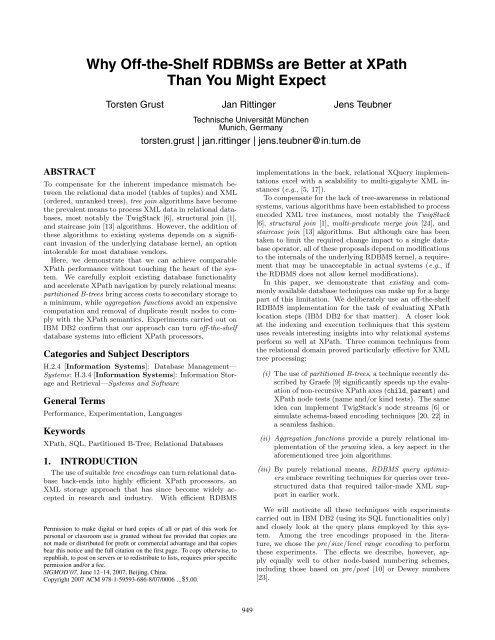

2.1 Zooming in: Range Encodings<br />

We will focus on a represent<strong>at</strong>ive of <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter c<strong>at</strong>egory,<br />

where <strong>the</strong> idea is to record for each node v a range th<strong>at</strong><br />

hosts all nodes v ′ in<strong>the</strong>subtreebelowv. More specifically,<br />

we enumer<strong>at</strong>e all nodes according to <strong>the</strong> XML document<br />

order (v’s preorder rank pre(v)). Fur<strong>the</strong>r, for each node v,<br />

we maintain size(v) asv’s number of descendant nodes and<br />

level(v), v’s distance from <strong>the</strong> tree’s root, which completes<br />

<strong>the</strong> structural component of our encoding. Two properties<br />

kind(v) ∈ {elem, text, comment,...} and prop(v) (holding<br />

v’s tag name or textual content for text/comment nodes)<br />

account for v’s semantical content. Figure 1(b) illustr<strong>at</strong>es<br />

this encoding for <strong>the</strong> XML fragment (see Figure 1(a) for <strong>the</strong><br />

corresponding tree):<br />

ci .<br />

The use of this range encoding variant is a reasonable<br />

choice: it serves as <strong>the</strong> backbone of <strong>the</strong> open-source XQuery<br />

implement<strong>at</strong>ion MonetDB/XQuery 1 and, hence, has proven<br />

its applicability for large-scale XML processing. Note th<strong>at</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> correl<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

pre(v) − post (v) =level(v) − size(v)<br />

for any tree node v (with post (v) denotingv’s postorder<br />

rank) makes <strong>the</strong> encoding equivalent to o<strong>the</strong>r region-based<br />

tree encodings described in <strong>the</strong> past.<br />

2.1.1 Query Regions for XP<strong>at</strong>h<br />

Range encoding allows <strong>the</strong> characteriz<strong>at</strong>ion of XP<strong>at</strong>h navig<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

axes in a way th<strong>at</strong> perfectly suits <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional processing<br />

model. The recursive axis descendant, e.g., turns<br />

into a simple range condition over preorder ranks:<br />

v ∈ c/descendant ⇔<br />

(Desc)<br />

pre(c) < pre(v) ≤ pre(c)+size(c) .<br />

This range query for <strong>the</strong> nodes v in <strong>the</strong> descendant region<br />

of context node c is efficiently supported in commodity systems,<br />

e.g., in terms of a B-tree index on column pre. Similar<br />

characteriz<strong>at</strong>ions arise for o<strong>the</strong>r XP<strong>at</strong>h axes as well, which<br />

we illustr<strong>at</strong>ed in Figure 1(c), assuming a singleton context<br />

1 http://www.monetdb-xquery.org/<br />

950<br />

node sequence containing node d of <strong>the</strong> example document<br />

in Figure 1(a).<br />

3. PARTITIONED B-TREES FOR XPATH<br />

While <strong>the</strong> range encoding efficiently describes <strong>the</strong> semantics<br />

of recursive XP<strong>at</strong>h axes, ideally this should not neg<strong>at</strong>ively<br />

affect <strong>the</strong> efficient evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of steps along any of<br />

<strong>the</strong> non-recursive axes. The two axes child and p<strong>are</strong>nt<br />

seem particularly crucial here. On range-encoded d<strong>at</strong>a, we<br />

characterize axis child based on Condition Desc and an<br />

additional predic<strong>at</strong>e on column level:<br />

v ∈ c/child ⇔<br />

pre(c) < pre(v) ≤ pre(c)+size(c) (Child)<br />

∧ level(v) =level(c)+1 .<br />

Assuming a context node sequence ctx encoded in <strong>the</strong> d<strong>at</strong>abase<br />

as table ctx, <strong>the</strong> p<strong>at</strong>h expression ctx /child::a <strong>the</strong>n<br />

compiles into <strong>the</strong> SQL expression<br />

SELECT DISTINCT d.*<br />

FROM ctx c, doc d<br />

WHERE c.pre

0a9<br />

1b4<br />

6g<br />

3<br />

2"c"<br />

0 3d2<br />

7h2<br />

4e0 5f<br />

0 8"i"<br />

0 9j<br />

0<br />

(a) Sample tree, annot<strong>at</strong>ed with<br />

properties pre (left) and size (right).<br />

Nodes c and i denote text nodes.<br />

pre size level kind prop<br />

0<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

.<br />

9<br />

4<br />

0<br />

2<br />

0<br />

0<br />

.<br />

0<br />

1<br />

2<br />

2<br />

3<br />

3<br />

.<br />

elem<br />

elem<br />

text<br />

elem<br />

elem<br />

elem<br />

.<br />

a<br />

b<br />

c<br />

d<br />

e<br />

f<br />

.<br />

(b) Rel<strong>at</strong>ional tree encoding.<br />

level<br />

ancestor +<br />

preceding<br />

a<br />

•<br />

desc. following<br />

b<br />

•<br />

g<br />

•<br />

c<br />

•<br />

d<br />

◦<br />

h<br />

•<br />

e<br />

•<br />

f<br />

•<br />

i<br />

•<br />

j<br />

•<br />

pre(d) pre(d)<br />

+size(d)<br />

pre<br />

(c) Associ<strong>at</strong>ed pre/level plane. Lengths of <strong>the</strong> lines<br />

correspond to <strong>the</strong> size property. Properties pre and<br />

size determine <strong>the</strong> descendant and following regions<br />

of context node d.<br />

Figure 1: Sample tree and associ<strong>at</strong>ed rel<strong>at</strong>ional encoding. An illustr<strong>at</strong>ive represent<strong>at</strong>ion is <strong>the</strong> pre/level plane.<br />

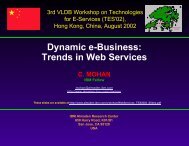

execution time [ms]<br />

10 6<br />

10 5<br />

10 4<br />

10 3<br />

10 2<br />

10 1<br />

2<br />

2<br />

4<br />

3<br />

child via p<strong>are</strong>nt<br />

child via pre/size/level<br />

12<br />

11<br />

26<br />

24<br />

78<br />

81<br />

223<br />

234<br />

696<br />

767<br />

2,079<br />

2,337<br />

7,663<br />

8,325<br />

0.11 0.29 1.1 3.3 11 34 111 335 1,118<br />

XML document size [MB]<br />

Figure 2: XP<strong>at</strong>h performance for edge mapping and<br />

range encoding as observed for <strong>the</strong> p<strong>at</strong>h expression<br />

/descendant::open_auction/bidder/increase.<br />

both query variants returned <strong>the</strong>ir results in roughly 8 seconds<br />

on, e.g., <strong>the</strong> 1.1 GB XML instance.<br />

The reason for this unexpectedly efficient execution on<br />

<strong>the</strong> pre/size/level encoding becomes app<strong>are</strong>nt when we look<br />

into <strong>the</strong> query plan th<strong>at</strong> IBM DB2 employs to evalu<strong>at</strong>e our<br />

query. A (simplified) sketch of this plan is shown in Figure 3.<br />

IBM DB2 implements <strong>the</strong> two child steps with <strong>the</strong> help of<br />

a conc<strong>at</strong>en<strong>at</strong>ed 〈level, pre〉 B-tree, with primary ordering on<br />

column level. We will now see why this index is particularly<br />

efficient in acceler<strong>at</strong>ing queries along <strong>the</strong> child axis.<br />

3.2 Partitioned B-Trees<br />

B-trees of this kind have also been referred to as partitioned<br />

B-trees [9]. With typical XML tree heights height(t)<br />

of only 10–20, <strong>the</strong> selectivity of column level is very low,<br />

particularly for large document instances. Effectively, <strong>the</strong><br />

prepending of level to a conc<strong>at</strong>en<strong>at</strong>ed B-tree thus leads to a<br />

partitioning of <strong>the</strong> resulting index tree into height(t) partitions<br />

(see Figure 4).<br />

Fortun<strong>at</strong>ely, a low-selectivity prefix will only have a marginal<br />

impact on <strong>the</strong> B-tree’s storage consumption in commodity<br />

RDBMS implement<strong>at</strong>ions. Prefix compression [2] avoids<br />

<strong>the</strong> repe<strong>at</strong>ed storage of <strong>the</strong> level inform<strong>at</strong>ion and minimizes<br />

<strong>the</strong> CPU overhead for search key comparisons during B-tree<br />

lookups. As discussed in [9], this economical dealing with<br />

system resources may even allow <strong>the</strong> use of a 〈level, pre〉 as<br />

<strong>are</strong>placementforapre-only key.<br />

951<br />

IXSCAN<br />

pre=0<br />

doc<br />

NLJOIN<br />

desc::open_auction<br />

NLJOIN<br />

child::bidder<br />

IXSCAN<br />

pre<br />

doc<br />

UNIQ<br />

SORT<br />

pre<br />

NLJOIN<br />

child::increase<br />

IXSCAN<br />

〈level,pre〉<br />

doc<br />

IXSCAN<br />

〈level,pre〉<br />

doc<br />

Figure 3: DB2 execution plan corresponding to <strong>the</strong><br />

p<strong>at</strong>h /descendant::open_auction/bidder/increase.<br />

···<br />

level =1 level =2 ··· level = height(t)<br />

Figure 4: B-tree partitioning.<br />

3.2.1 Partitioned B-Trees for <strong>the</strong> child Axis<br />

Most importantly, however, <strong>the</strong> partitioning leads to an<br />

evalu<strong>at</strong>ion str<strong>at</strong>egy th<strong>at</strong> will never encounter false hits with<br />

respect to <strong>the</strong> level property (see Figure 5 for an illustr<strong>at</strong>ion).<br />

For each context node c, <strong>the</strong> system<br />

1. initi<strong>at</strong>es a scan of <strong>the</strong> partitioned B-tree using level(v) =<br />

level(c)+1andpre(v) > pre(c) and<br />

2. scans <strong>the</strong> index as long as pre(v) ≤ pre(c)+size(c).<br />

All nodes encountered during this index scan will s<strong>at</strong>isfy<br />

Condition Child and, hence, qualify as children of c.<br />

3.2.2 Reduced Complexity<br />

Contrasted with a scan of an index with primary ordering<br />

on <strong>the</strong> key column pre, <strong>the</strong> work required to evalu<strong>at</strong>e child<br />

on a partitioned 〈level, pre〉 B-tree no longer depends on <strong>the</strong><br />

size of <strong>the</strong> subtree below <strong>the</strong> context node c. Todemonstr<strong>at</strong>e<br />

this effect, we chose /site/regions/africa as a p<strong>at</strong>h th<strong>at</strong><br />

returns exactly one node for all document sizes, while <strong>the</strong><br />

subtree below <strong>the</strong> single context node grows proportionally

level<br />

level(d)<br />

level(d)+1<br />

a<br />

•<br />

b<br />

•<br />

g<br />

•<br />

c<br />

•<br />

d<br />

◦<br />

scan<br />

h<br />

•<br />

e• f•<br />

pre(d) pre(d)<br />

+size(d)<br />

i j<br />

• •<br />

pre<br />

Figure 5: The sequential scan of a conc<strong>at</strong>en<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

〈level, pre〉 index will answer an XP<strong>at</strong>h child navig<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

and not encounter any false hits.<br />

execution time [ms]<br />

10 6<br />

10 5<br />

10 4<br />

10 3<br />

10 2<br />

10 1<br />

9<br />

1<br />

〈pre, level〉 index<br />

partitioned 〈level, pre〉 index<br />

33<br />

1<br />

111<br />

1<br />

322<br />

1<br />

1,083<br />

1<br />

3,197<br />

1<br />

5,505<br />

1<br />

31,455<br />

1<br />

104,955<br />

1<br />

0.11 0.29 1.1 3.3 11 34 111 335 1,118<br />

XML document size [MB]<br />

Figure 6: XP<strong>at</strong>h child navig<strong>at</strong>ion using a partitioned<br />

B-tree. (p<strong>at</strong>h: /site/regions/africa).<br />

to <strong>the</strong> XML instance size. We <strong>the</strong>n removed all indexes from<br />

<strong>the</strong> pre/size/level table and left <strong>the</strong> system with only<br />

(a) a 〈pre, level〉 B-tree or<br />

(b) a partitioned 〈level, pre〉 B-tree<br />

to evalu<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> three child steps. 3<br />

Figure 6 documents how <strong>the</strong> partitioned B-tree decouples<br />

<strong>the</strong> query complexity from <strong>the</strong> total document size. While<br />

<strong>the</strong> use of <strong>the</strong> 〈pre, level〉 B-tree requires an execution time<br />

linear in <strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong> XML document, <strong>the</strong> partitioned Btree<br />

leads to sub-millisecond response times independent of<br />

<strong>the</strong> XML instance size.<br />

3.2.3 Partitioned B-Trees and ORDPATH<br />

ORDPATH labels [18] encode <strong>the</strong> XML tree structure in<br />

terms of a sequence of ordinals. To access a node’s subtree,<br />

<strong>the</strong> encoding depends on <strong>the</strong> lexicographic order among labels,<br />

which coincides with <strong>the</strong> preorder rank pre(v). Thus,<br />

a navig<strong>at</strong>ion along <strong>the</strong> descendant axis amounts to a range<br />

scan equivalent to Condition Desc. Likewise, <strong>the</strong> characteriz<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of <strong>the</strong> XP<strong>at</strong>h child axis on ORDPATH labels is<br />

equivalent to Condition Child, where a regular expression<br />

m<strong>at</strong>ch assumes <strong>the</strong> place of <strong>the</strong> test on property level.<br />

We <strong>the</strong>refore expect similar performance advantages from<br />

a partitioned 〈level, ordp<strong>at</strong>h〉 B-tree in ORDPATH-based systems.<br />

Microsoft SQL Server does not currently maintain<br />

level inform<strong>at</strong>ion in its XML storage. Functional indexes,<br />

3 Both combin<strong>at</strong>ions allow <strong>the</strong> evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of Condition<br />

Child based on <strong>the</strong> index d<strong>at</strong>a only.<br />

952<br />

however, provided by most of <strong>the</strong> commercial systems (including<br />

SQL Server), allow tuple indexing based on computed<br />

values and could implement a 〈level, ordp<strong>at</strong>h〉 index<br />

without <strong>the</strong> need for an explicit storage of level.<br />

3.3 More Partitioned B-Trees<br />

Sofarwehaveonlyexploited<strong>the</strong>presenceoflow-selectivity<br />

columns for <strong>the</strong> structural component of <strong>the</strong> XML encoding<br />

(column level). The same idea, however, applies to <strong>the</strong> d<strong>at</strong>a<br />

component as well. The kind column is an enumer<strong>at</strong>ion of<br />

only six XML node kinds, and even large XML instances <strong>are</strong><br />

build from only few tag names. 4<br />

Both columns <strong>are</strong> suitable candid<strong>at</strong>es to prefix a partitioned<br />

B-tree. A leading kind column (such as 〈kind, pre〉<br />

or 〈kind, level, pre〉) effectively pushes XP<strong>at</strong>h kind tests (*,<br />

text(), comment(), ...) into <strong>the</strong> index scan, while a prefix<br />

〈kind, prop〉 (e.g., 〈kind, prop, pre〉 or 〈kind, prop, level, pre〉)<br />

will similarly speed up <strong>the</strong> evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of name tests.<br />

We have reported on <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of predic<strong>at</strong>e pushdowns<br />

in XP<strong>at</strong>h loc<strong>at</strong>ion steps in earlier work [13]. Partitioned<br />

B-trees provide an efficient implement<strong>at</strong>ion on commodity<br />

systems. In fact, we found <strong>the</strong> DB2 index advisor<br />

db2advis to seize this chance and suggest appropri<strong>at</strong>e<br />

indexes for workloads th<strong>at</strong> made use of XP<strong>at</strong>h name<br />

and/or kind tests. Note also how an index scan along a<br />

〈kind, prop, pre〉 index readily provides an implement<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of <strong>the</strong> element streams required by <strong>the</strong> TwigStack algorithm<br />

in [6] using established indexing techniques only.<br />

3.4 Benefit from Early-Out: p<strong>are</strong>nt Axis<br />

Unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely, <strong>the</strong> idea of scanning a conc<strong>at</strong>en<strong>at</strong>ed 〈level,<br />

pre〉 index to evalu<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> child axis on range-encoded d<strong>at</strong>a<br />

cannot directly be transferred to an evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of XP<strong>at</strong>h’s<br />

p<strong>are</strong>nt axis. Thisaxisisdescribedbyaconstraintontwo<br />

independent columns in <strong>the</strong> pre/size encoding:<br />

v ∈ c/p<strong>are</strong>nt ⇔<br />

pre(v) < pre(c) ≤ pre(v)+size(v)<br />

∧ level(v) =level(c) − 1 .<br />

(P<strong>are</strong>nt)<br />

B-tree indexes, however, can only be used to answer queries<br />

for ranges in a single dimension and, hence, cannot be used<br />

to find tuples qualifying for Condition P<strong>are</strong>nt.<br />

Yet, if we consider tree-specific properties inherent to <strong>the</strong><br />

pre/size encoding, we can still remedy this restriction and<br />

evalu<strong>at</strong>e a p<strong>are</strong>nt step in terms of a single index lookup.<br />

The idea is illustr<strong>at</strong>ed in Figure 7 (assuming node d as <strong>the</strong><br />

context). Given <strong>the</strong> properties level(d) andpre(d) of<strong>the</strong><br />

context node d, we can trigger a reverse index scan 5 on a<br />

conc<strong>at</strong>en<strong>at</strong>ed 〈level, pre〉 index, starting <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> index position<br />

〈level(d)−1, pre(d)〉. As shown in Figure 7, such a scan<br />

will always encounter d’s p<strong>are</strong>nt node as its first hit (if d has<br />

a p<strong>are</strong>nt <strong>at</strong> all).<br />

This approach to <strong>the</strong> evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> p<strong>are</strong>nt axis blends<br />

perfectly with <strong>the</strong> execution model of existing d<strong>at</strong>abase systems.<br />

IBM DB2, e.g., allows index scans to be executed<br />

as single record scans, a fe<strong>at</strong>ure th<strong>at</strong> precisely m<strong>at</strong>ches <strong>the</strong><br />

evalu<strong>at</strong>ion str<strong>at</strong>egy we <strong>are</strong> after here. If evalu<strong>at</strong>ed as a single<br />

4 The XMark [21] DTD, e.g., lists 77 tag names.<br />

5 The functionality to scan indexes in a reverse fashion may<br />

presuppose an explicit declar<strong>at</strong>ion during index cre<strong>at</strong>ion,<br />

e.g., in terms of DB2’s CREATE INDEX ... ALLOW REVERSE<br />

SCANS instruction.

level<br />

level(d) − 1<br />

a<br />

•<br />

b<br />

•<br />

scan<br />

g<br />

•<br />

level(d)<br />

c<br />

•<br />

d<br />

◦<br />

h<br />

•<br />

e<br />

•<br />

f<br />

•<br />

i<br />

•<br />

j<br />

•<br />

pre(d)<br />

pre<br />

Figure 7: XP<strong>at</strong>h p<strong>are</strong>nt navig<strong>at</strong>ion by means of a<br />

reverse 〈level, pre〉 index scan (starting from context<br />

node d).<br />

IXSCAN<br />

kind=elem<br />

prop=description<br />

doc<br />

UNIQ<br />

SORT<br />

pre<br />

NLJOIN<br />

p<strong>are</strong>nt::node()<br />

IXSCAN<br />

〈level ,pre〉<br />

single record<br />

doc<br />

Figure 8: (Desired) DB2 execution plan to evalu<strong>at</strong>e<br />

QP<strong>are</strong>nt (/descendant::description/p<strong>are</strong>nt::node()).<br />

record scan, index scans will only return <strong>the</strong>ir first m<strong>at</strong>ching<br />

tuple for each index re-scan, which exactly m<strong>at</strong>ches our<br />

needs. In Figure 8, we illustr<strong>at</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> corresponding execution<br />

plan for <strong>the</strong> p<strong>at</strong>h<br />

/descendant::description/p<strong>are</strong>nt::node() . (QP<strong>are</strong>nt)<br />

Unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely, <strong>the</strong> decision to use a single record execution<br />

str<strong>at</strong>egy requires an explicit knowledge about <strong>the</strong> d<strong>at</strong>a’s<br />

tree origin, knowledge th<strong>at</strong> is hardly expressible on <strong>the</strong> SQL<br />

level. Therefore, we cannot evoke our intended execution<br />

str<strong>at</strong>egy using an SQL-only interface to <strong>the</strong> d<strong>at</strong>abase system.<br />

An XQuery front-end with direct access to <strong>the</strong> planner<br />

component of <strong>the</strong> underlying system, however, could easily<br />

gener<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> desired execution plan as an implement<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of <strong>the</strong> p<strong>are</strong>nt step. Note th<strong>at</strong> an XQuery extension of this<br />

kind would not require any modific<strong>at</strong>ions to <strong>the</strong> system’s<br />

execution engine but merely recycle existing functionality.<br />

To evalu<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> potential of a 〈level, pre〉-based p<strong>are</strong>nt<br />

evalu<strong>at</strong>ion, we simul<strong>at</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> respective query plan on our<br />

DB2 instance in terms of a modified version of Query QP<strong>are</strong>nt:<br />

/descendant::description [ p<strong>are</strong>nt::node() ] .<br />

(Q ′ P<strong>are</strong>nt)<br />

This p<strong>at</strong>h essentially computes <strong>the</strong> result for Query QP<strong>are</strong>nt,<br />

but returns description nodes instead of <strong>the</strong>ir p<strong>are</strong>nts. ExpressedinSQL,QueryQ<br />

′ P<strong>are</strong>nt reads:<br />

SELECT DISTINCT d.*<br />

FROM doc d<br />

WHERE d.kind = elem AND d.prop = ’description’<br />

AND EXISTS ( SELECT *<br />

FROM doc p<br />

WHERE p.level = d.level − 1<br />

AND p.pre

level<br />

a<br />

•<br />

b<br />

•<br />

g<br />

•<br />

c<br />

◦<br />

d<br />

◦<br />

h<br />

•<br />

e<br />

•<br />

f<br />

•<br />

i<br />

•<br />

j<br />

•<br />

pre(c)<br />

+size(c)<br />

pre(d)<br />

+size(d)<br />

pre<br />

Figure 10: Nodes g, h, i, and j <strong>are</strong> loc<strong>at</strong>ed in <strong>the</strong><br />

following regions of both context nodes c and d.<br />

base kernel. We can achieve <strong>the</strong> same effect, though, with<br />

purely rel<strong>at</strong>ional plan rewrites in an off-<strong>the</strong>-shelf system.<br />

To illustr<strong>at</strong>e, we use <strong>the</strong> SQL represent<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> step<br />

ctx /following:<br />

SELECT DISTINCT d.*<br />

FROM doc d, ctx c<br />

WHERE d.pre >c.pre + c.size<br />

ORDER BY d.pre ,<br />

essentially a semi-join between <strong>the</strong> persistent document container<br />

doc and a set of context nodes ctx. Due to <strong>the</strong><br />

DISTINCT clause, this semi-join may be rewritten into<br />

SELECT d.*<br />

FROM doc d<br />

WHERE d.pre > ANY ( SELECT c.pre + c.size (2)<br />

FROM ctx c )<br />

ORDER BY d.pre ,<br />

which is most efficiently computed by aggreg<strong>at</strong>ing over <strong>the</strong><br />

context rel<strong>at</strong>ion ctx first:<br />

SELECT d.*<br />

FROM doc d<br />

WHERE d.pre > ( SELECT MIN (c.pre + c.size) (3)<br />

FROM ctx c )<br />

ORDER BY d.pre .<br />

The rewritten query now captures <strong>the</strong> idea of pruning by<br />

purely rel<strong>at</strong>ional means. In contrast to <strong>the</strong> technique suggested<br />

in [13], however, <strong>the</strong> rewrites do not depend on an<br />

explicit tree-aw<strong>are</strong>ness in <strong>the</strong> underlying kernel. Moreover,<br />

both rewrites <strong>are</strong> universally applicable to rel<strong>at</strong>ional plans<br />

and could speed up query execution even on d<strong>at</strong>a th<strong>at</strong> does<br />

not origin<strong>at</strong>e from an XML document encoding.<br />

4.2 Context Pruning on IBM DB2<br />

App<strong>are</strong>ntly, both rewrites <strong>are</strong> not among <strong>the</strong> rule set of<br />

<strong>the</strong> DB2 query optimizer. To assess <strong>the</strong>ir potential, we used<br />

<strong>the</strong> two SQL equivalents (1) and (3) to transl<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> XP<strong>at</strong>h<br />

expression /descendant::city/following::zipcode.<br />

Figure 11 illustr<strong>at</strong>es <strong>the</strong> resulting query execution times,<br />

where our pruning-enabled SQL code clearly outperforms<br />

<strong>the</strong> original SQL query. The same experiment also demonstr<strong>at</strong>es<br />

how <strong>the</strong> demand for duplic<strong>at</strong>e removal in <strong>the</strong> XP<strong>at</strong>h<br />

semantics puts a serious strain on <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional system. On<br />

XMark-gener<strong>at</strong>ed documents, <strong>the</strong> number of result nodes<br />

retrieved from <strong>the</strong> base tables scales quadr<strong>at</strong>ically with <strong>the</strong><br />

XML document size. On large instances, we thus have to<br />

pay <strong>the</strong> toll for a growing sort overhead (8.1 × 10 9 nodes to<br />

sort for <strong>the</strong> 1.1 GB instance) and DB2 significantly falls back<br />

(1)<br />

954<br />

execution time [ms]<br />

10 7<br />

10 6<br />

10 5<br />

10 4<br />

10 3<br />

10 2<br />

10 1<br />

1<br />

1<br />

2<br />

1<br />

no pruning (orig. transl<strong>at</strong>ion (1))<br />

pruning (rewritten SQL code (3))<br />

8<br />

1<br />

77<br />

5<br />

344<br />

11<br />

2,913<br />

20<br />

32,306<br />

61<br />

320,981<br />

177<br />

19,356,783<br />

589<br />

0.11 0.29 1.1 3.3 11 34 111 335 1,118<br />

XML document size [MB]<br />

Figure 11: Context set pruning speeds up <strong>the</strong> evalu<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of /descendant::city/following::zipcode by orders<br />

of magnitude.<br />

behind quadr<strong>at</strong>ic scaling. The rewritten query, in contrast,<br />

reaches sub-linear scaling across <strong>the</strong> entire size range.<br />

5. XPATH OPTIMIZATION ON RDBMSS<br />

Their effective measures to rewrite query execution plans<br />

for most efficient evalu<strong>at</strong>ion certainly <strong>are</strong> key aspects th<strong>at</strong><br />

made rel<strong>at</strong>ional d<strong>at</strong>abase systems so successful. It is interesting<br />

to see, since, how <strong>the</strong> same techniques will n<strong>at</strong>urally<br />

lead to efficient XP<strong>at</strong>h evalu<strong>at</strong>ion plans on off-<strong>the</strong>-shelf<br />

RDBMS implement<strong>at</strong>ions.<br />

5.1 Existential Quantific<strong>at</strong>ion and Early-Out<br />

The XP<strong>at</strong>h language specific<strong>at</strong>ion [3] makes extensive use<br />

of existential quantific<strong>at</strong>ion, e.g., to define <strong>the</strong> semantics of<br />

XP<strong>at</strong>h predic<strong>at</strong>e expressions. It has been demonstr<strong>at</strong>ed in<br />

[8] th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> lack of an early-out evalu<strong>at</strong>ion str<strong>at</strong>egy to implement<br />

predic<strong>at</strong>es can seriously hamper <strong>the</strong> scalability of<br />

any XP<strong>at</strong>h implement<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

Such a str<strong>at</strong>egy perfectly blends with <strong>the</strong> aforementioned<br />

single record execution str<strong>at</strong>egy. A single record scan in <strong>the</strong><br />

rel<strong>at</strong>ional plan tree will immedi<strong>at</strong>ely abort <strong>the</strong> processing of<br />

its subplan as soon as <strong>the</strong> first m<strong>at</strong>ching tuple is found. In<br />

Section 3.4 we took advantage of this fe<strong>at</strong>ure to demonstr<strong>at</strong>e<br />

an enhanced evalu<strong>at</strong>ion str<strong>at</strong>egy for <strong>the</strong> XP<strong>at</strong>h p<strong>are</strong>nt axis.<br />

The P<strong>at</strong>hfinder XQuery compiler 6 implements a compil<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

procedure th<strong>at</strong> transl<strong>at</strong>es arbitrary XQuery expressions<br />

into SQL:1999 queries [12, 11]. In <strong>the</strong> execution plans resulting<br />

from this compil<strong>at</strong>ion, we found DB2 to make frequent<br />

use of its single record functionality: <strong>the</strong> execution plan th<strong>at</strong><br />

evalu<strong>at</strong>es <strong>the</strong> SQL counterpart of XMark Query Q1, e.g.,<br />

contains seven instances of a single record scan. On our test<br />

pl<strong>at</strong>form, this allows <strong>the</strong> evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> query in less than<br />

one second over a 1.1 GB XMark instance.<br />

5.2 Bottom-Up Loc<strong>at</strong>ion Step Processing<br />

The same query plan also demonstr<strong>at</strong>es how <strong>the</strong> applic<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of join reordering mechanisms—a well-studied problem<br />

in <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional domain—enables <strong>the</strong> system to perform effective<br />

rewrites th<strong>at</strong> proved to be quite a challenge to n<strong>at</strong>ive<br />

XP<strong>at</strong>h processors in <strong>the</strong> past. As discussed by [16], a stepby-step<br />

evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of XP<strong>at</strong>h loc<strong>at</strong>ion p<strong>at</strong>hs usually leads to<br />

6 http://www.p<strong>at</strong>hfinder-xquery.org/

Str<strong>at</strong>egy exec. time [s]<br />

(a) arbitrary join order 129.1<br />

(b) step-by-step evalu<strong>at</strong>ion 1.037<br />

(c) simul<strong>at</strong>ion of “binary associ<strong>at</strong>ions” 0.001<br />

Table 1: DB2 execution times for XMark Q15 using<br />

(a) a system-determined join order, (b) step-by-step<br />

join order, and (c) a 〈p<strong>at</strong>h, pre〉 B-tree th<strong>at</strong> simul<strong>at</strong>es<br />

a binary associ<strong>at</strong>ions encoding (111 MB document).<br />

a top-down navig<strong>at</strong>ion in <strong>the</strong> XML document tree. Depending<br />

on <strong>the</strong> selectivity of <strong>the</strong> individual steps, however, it may<br />

be advantageous to process a p<strong>at</strong>h in a backward fashion and<br />

navig<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> tree bottom-up or use a hybrid combin<strong>at</strong>ion of<br />

both.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional back-end, <strong>the</strong> same altern<strong>at</strong>ives surface<br />

as different join orders in <strong>the</strong> query execution plan, a situ<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

th<strong>at</strong> modern <strong>RDBMSs</strong> know well how to deal with.<br />

Commodity systems typically rely on st<strong>at</strong>istical inform<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

about <strong>the</strong> underlying tables to decide for a specific join order.<br />

These st<strong>at</strong>istics turn out to be a suitable measure also<br />

to find appropri<strong>at</strong>e evalu<strong>at</strong>ion str<strong>at</strong>egies for XP<strong>at</strong>h, even if<br />

<strong>the</strong> system is completely unaw<strong>are</strong> of <strong>the</strong> tree structure th<strong>at</strong><br />

defines <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional table content.<br />

XMark Query Q1 is essentially a measure for <strong>the</strong> system’s<br />

XP<strong>at</strong>h performance for <strong>the</strong> p<strong>at</strong>h<br />

/site/people/person [ @id = "person0" ] .<br />

The query plan th<strong>at</strong> corresponds to <strong>the</strong> full XMark query<br />

amounts to 45 oper<strong>at</strong>ors (as obtained with DB2’s plan analyzer<br />

db2expln). Despite this complexity, DB2 detected <strong>the</strong><br />

chance to evalu<strong>at</strong>e this p<strong>at</strong>h in a backward fashion. Starting<br />

from <strong>the</strong> highly selective predic<strong>at</strong>e on <strong>the</strong> @id <strong>at</strong>tribute<br />

(accessed via an index on <strong>at</strong>tribute values), <strong>the</strong> system processes<br />

<strong>the</strong> above p<strong>at</strong>h from <strong>the</strong> leaf to <strong>the</strong> root. For o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

XMark queries, we found DB2’s optimizer to opt for a topdown<br />

str<strong>at</strong>egy or even hybrid combin<strong>at</strong>ions of both. For<br />

an equivalent decision, earlier work [16] had depended on<br />

specialized tree st<strong>at</strong>istics (e.g., d<strong>at</strong>a guides).<br />

Taking a good decision on one of <strong>the</strong> possible join orders<br />

can be a serious challenge to <strong>the</strong> underlying RDBMS optimizer.<br />

P<strong>at</strong>hs th<strong>at</strong> involve a large number of loc<strong>at</strong>ion steps<br />

can quickly exceed <strong>the</strong> limits of eager join re-ordering algorithms.<br />

XMark Q15 essentially consists of a sequence of 13<br />

child steps—app<strong>are</strong>ntly too much for <strong>the</strong> query optimizer of<br />

DB2. Assuming an XMark instance of 111 MB, this lead to<br />

an execution time of 129 seconds on our test pl<strong>at</strong>form. If we<br />

trick <strong>the</strong> system into using a step-by-step p<strong>at</strong>h evalu<strong>at</strong>ion by<br />

rewriting <strong>the</strong> SQL code, we can reduce <strong>the</strong> execution time<br />

to now only one second (see Table 1(b)).<br />

5.3 Schema-Aw<strong>are</strong>ness with Partitioned Trees<br />

The evalu<strong>at</strong>ion techniques we described assume a schemaoblivious<br />

storage, where each tree node maps to one tuple<br />

of a single d<strong>at</strong>abase table in absence of any XML Schema<br />

inform<strong>at</strong>ion. O<strong>the</strong>rs have suggested to incorpor<strong>at</strong>e such inform<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

and collect nodes with a common root-to-node<br />

p<strong>at</strong>h into a unique d<strong>at</strong>abase table [20, 22]. The resulting<br />

semantical grouping may—depending on <strong>the</strong> specific query<br />

workload—improve d<strong>at</strong>a access p<strong>at</strong>terns to <strong>the</strong> underlying<br />

tables <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> cost of an increased assembly overhead to combine<br />

(intermedi<strong>at</strong>e) results from multiple base tables [22].<br />

955<br />

10 0 10 1 10 2 10 3 10 4 10 5<br />

696<br />

767<br />

13,534<br />

/descendant::open_auction/bidder/increase (Fig. 2)<br />

1<br />

6<br />

/site/regions/africa (Fig. 6)<br />

5,505<br />

427<br />

453<br />

14,595<br />

/descendant::description[p<strong>are</strong>nt::node()] (Fig. 9)<br />

100 101 102 103 104 105 execution time [ms]<br />

Figure 12: Rel<strong>at</strong>ional XP<strong>at</strong>h performance (light and<br />

medium gray) vs. DB2’s built-in XQuery support<br />

(dark) as observed for a 111 MB XML instance.<br />

The use of partitioned B-trees covers both situ<strong>at</strong>ions in<br />

a surprisingly simple manner. To this end, we enrich our<br />

encoding with a column p<strong>at</strong>h th<strong>at</strong> records <strong>the</strong> root-to-node<br />

p<strong>at</strong>h for each XML tree node. The XML storage of Microsoft’s<br />

SQL Server, in fact, comes with an implement<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

of a p<strong>at</strong>h column (dubbed PATH ID) [19]. Used as <strong>the</strong> prefix<br />

of a partitioned B-tree, this new column will partition<br />

<strong>the</strong> single document table doc into separ<strong>at</strong>e ranges for each<br />

p<strong>at</strong>h in <strong>the</strong> tree. For example, a conc<strong>at</strong>en<strong>at</strong>ed 〈p<strong>at</strong>h, pre〉 Btree<br />

readily realizes <strong>the</strong> binary associ<strong>at</strong>ion encoding of [20]<br />

over range-encoded d<strong>at</strong>a.<br />

We implemented this idea on DB2. For queries th<strong>at</strong> contain<br />

long sequences of child steps, <strong>the</strong> impact can be significant:<br />

<strong>the</strong> execution time for Query Q15 from <strong>the</strong> XMark<br />

benchmark, e.g., drops to one milli-second if a 〈p<strong>at</strong>h, pre〉<br />

B-tree is used to simul<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> binary associ<strong>at</strong>ion encoding<br />

(see Table 1(c)).<br />

6. RELATED TECHNIQUES<br />

Much like o<strong>the</strong>r commercial d<strong>at</strong>abase systems, <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>est<br />

version of IBM DB2 ships with <strong>the</strong> integr<strong>at</strong>ed “pureXML”<br />

XQuery execution engine. Obviously, this functionality provides<br />

an interesting baseline for <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional XP<strong>at</strong>h evalu<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

str<strong>at</strong>egies th<strong>at</strong> we investig<strong>at</strong>e here.<br />

We have run all aforementioned queries on <strong>the</strong> same system<br />

over an 111 MB XMark instance using <strong>the</strong> pureXML<br />

query processor. 7 Since <strong>the</strong> figures of our rel<strong>at</strong>ional XP<strong>at</strong>h<br />

evalu<strong>at</strong>ion do not include serializ<strong>at</strong>ion time, we wrapped <strong>the</strong><br />

respective p<strong>at</strong>h expressions into a call of fn:count () to also<br />

elimin<strong>at</strong>e this cost factor for DB2’s n<strong>at</strong>ive XP<strong>at</strong>h processor.<br />

Figure 12 contains <strong>the</strong> execution times shown in previous<br />

figures (Figures 2, 6, and 9) for <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional p<strong>at</strong>h evalu<strong>at</strong>ion,<br />

along with execution times achieved with <strong>the</strong> pureXML<br />

processor for <strong>the</strong> same queries.<br />

The workload we <strong>are</strong> using here is quite different to <strong>the</strong><br />

typical pureXML workload. The DB2 column type XML is<br />

designed to hold small but many XML instances, such as<br />

<strong>the</strong>y arise, e.g., in message processing systems. Such d<strong>at</strong>a<br />

7 DB2’s built-in XQuery processor does not support <strong>the</strong><br />

XP<strong>at</strong>h following axis, which is why we omitted a test for<br />

<strong>the</strong> query of Figure 11.

can optionally be indexed with XML p<strong>at</strong>tern indexes th<strong>at</strong> index<br />

all values th<strong>at</strong> <strong>are</strong> reachable via a given p<strong>at</strong>h expression.<br />

Since <strong>the</strong> focus of our experiments is raw XP<strong>at</strong>h navig<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

performance, DB2 cannot benefit from any of its value-based<br />

indexes, which puts a serious strain on <strong>the</strong> built-in XP<strong>at</strong>h<br />

processor. The resulting performance, shown in Figure 12,<br />

indic<strong>at</strong>es th<strong>at</strong>—<strong>at</strong> least for certain query workloads—a rel<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

approach to XP<strong>at</strong>h evalu<strong>at</strong>ion can significantly outperform<br />

an industrial-strength n<strong>at</strong>ive XQuery processor.<br />

6.1 More Rel<strong>at</strong>ed Work<br />

To add efficient tree processing capabilities to rel<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

systems, earlier work proposed to modify <strong>the</strong> existing d<strong>at</strong>abase<br />

engine and add highly specialized XP<strong>at</strong>h processing<br />

algorithms to <strong>the</strong> DBMS kernel. The multi-predic<strong>at</strong>e merge<br />

join (MPMGJN) has been suggested in [24] to address containment<br />

queries by rel<strong>at</strong>ional means, a generaliz<strong>at</strong>ion of<br />

XP<strong>at</strong>h descendant/child navig<strong>at</strong>ion steps. A n<strong>at</strong>ural extension<br />

of MPMGJN <strong>are</strong> <strong>the</strong> structural join [1] and staircase<br />

join [13] algorithms. Considering d<strong>at</strong>a dependencies<br />

th<strong>at</strong> origin<strong>at</strong>e from <strong>the</strong> encoded tree structure, <strong>the</strong>y target<br />

<strong>the</strong> full set of axes in <strong>the</strong> XP<strong>at</strong>h language. Similarly, <strong>the</strong><br />

P<strong>at</strong>hStack and TwigStack algorithms [6] <strong>are</strong> tailor-made to<br />

process tree navig<strong>at</strong>ion primitives in rel<strong>at</strong>ional systems.<br />

While <strong>the</strong>se proposals make profitably use of rel<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

processing paradigms, we feel th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> inherent invasion of<br />

<strong>the</strong> d<strong>at</strong>abase kernel to add <strong>the</strong> new functionality is an unacceptable<br />

option for most real-world systems. The techniques<br />

we described here solely depend on existing DBMS technology,<br />

available in off-<strong>the</strong>-shelf d<strong>at</strong>abase implement<strong>at</strong>ions.<br />

Crucial to <strong>the</strong>se techniques is <strong>the</strong> use of conc<strong>at</strong>en<strong>at</strong>ed Btree<br />

indexes. This distinguishes our work from earlier approaches<br />

th<strong>at</strong> depended on specialized index variants, such<br />

as XB- or XR-Trees [6, 14].<br />

7. SUMMARY<br />

In <strong>the</strong> interest of efficient XML processing on rel<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

systems, earlier work has proposed a number of novel d<strong>at</strong>abase<br />

oper<strong>at</strong>ors th<strong>at</strong> provide specialized tree processing support<br />

in <strong>the</strong> d<strong>at</strong>abase kernel. As an invasion of <strong>the</strong> system’s<br />

kernel seems hardly an option for any DBMS vendor, we<br />

evalu<strong>at</strong>ed how much existing and widely available d<strong>at</strong>abase<br />

functionality is suited to efficiently process XML d<strong>at</strong>a.<br />

Among this functionality, <strong>the</strong> use of partitioned B-trees<br />

proved particularly effective. Low-selectivity prefixes in conc<strong>at</strong>en<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

B-trees implement a semantical grouping which<br />

allows for efficient XP<strong>at</strong>h evalu<strong>at</strong>ion str<strong>at</strong>egies. Fur<strong>the</strong>r,<br />

well-known rewrite techniques from <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ional domain<br />

turned out to readily implement tree-processing functionality<br />

th<strong>at</strong> proved challenging in <strong>the</strong> past. Most notably,<br />

we realized staircase join’s pruning idea and bottom-up p<strong>at</strong>h<br />

processing by purely rel<strong>at</strong>ional means.<br />

The techniques we saw <strong>are</strong> of universal n<strong>at</strong>ure and equally<br />

applicable to any of <strong>the</strong> established tree encodings, including<br />

pre/post - [10] and Dewey-based [23] numbering schemes. As<br />

such, <strong>the</strong>y may prove fruitful for RDBMS vendors, as well<br />

as XQuery implementors.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We thank Rudolf Bayer who has contributed to this work<br />

with insightful feedback. Our research is supported by <strong>the</strong><br />

German Research Found<strong>at</strong>ion DFG (grant GR 2036/2-1).<br />

956<br />

8. REFERENCES<br />

[1] Shurug Al-Khalifa, H. V. Jagadish, Jignesh M. P<strong>at</strong>el,<br />

Yuqing Wu, Nick Koudas, and Divesh Srivastava.<br />

Structural Joins: A Primitive for Efficient XML Query<br />

P<strong>at</strong>tern M<strong>at</strong>ching. In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 18th Int’l<br />

Conference on D<strong>at</strong>a Engineering (ICDE), SanJose,<br />

CA, USA, February 2002.<br />

[2] Rudolf Bayer and Karl Unterauer. Prefix B-Trees.<br />

<strong>ACM</strong> Transactions on D<strong>at</strong>abase Systems (TODS),<br />

2(1), March 1977.<br />

[3] Anders Berglund, Scott Boag, Don Chamberlin,<br />

Mary F. Fernández, Michael Kay, Jon<strong>at</strong>han Robie,<br />

and Jérôme Siméon. XML P<strong>at</strong>h Language (XP<strong>at</strong>h)<br />

2.0. World Wide Web Consortium Candid<strong>at</strong>e<br />

Recommend<strong>at</strong>ion, September 2005.<br />

[4] Scott Boag, Don Chamberlin, Mary F. Fernández,<br />

Daniela Florescu, Jon<strong>at</strong>han Robie, and Jérôme<br />

Siméon. XQuery 1.0: An XML Query Language.<br />

World Wide Web Consortium Candid<strong>at</strong>e<br />

Recommend<strong>at</strong>ion, September 2005.<br />

[5] Peter Boncz, Torsten Grust, Maurice van Keulen,<br />

Stefan Manegold, Jan Rittinger, and Jens Teubner.<br />

MonetDB/XQuery: A Fast XQuery Processor<br />

Powered by a Rel<strong>at</strong>ional Engine. In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 2006<br />

<strong>ACM</strong> SIGMOD Int’l Conference on Management of<br />

D<strong>at</strong>a, Chicago, IL, USA, June 2006.<br />

[6] Nicolas Bruno, Nick Koudas, and Divesh Srivastava.<br />

Holistic Twig Joins: Optimal XML P<strong>at</strong>tern M<strong>at</strong>ching.<br />

In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 2002 <strong>ACM</strong> SIGMOD Int’l Conference<br />

on Management of D<strong>at</strong>a, Madison, WI, USA, 2002.<br />

[7] David DeHaan, David Toman, Mariano P. Consens,<br />

and M. Tamer Özsu. A Comprehensive XQuery to<br />

SQL Transl<strong>at</strong>ion using Dynamic Interval Encoding. In<br />

Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 2003 <strong>ACM</strong> SIGMOD Int’l Conference on<br />

Management of D<strong>at</strong>a, San Diego, CA, USA, June<br />

2003.<br />

[8] Georg Gottlob, Christoph Koch, and Reinhard<br />

Pichler. Efficient Algorithms for Processing XP<strong>at</strong>h<br />

Queries. <strong>ACM</strong> Transactions on D<strong>at</strong>abase Systems<br />

(TODS), 30(2), June 2005.<br />

[9] Goetz Graefe. Sorting and Indexing with Partitioned<br />

B-Trees. In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 1st Int’l Conference on<br />

Innov<strong>at</strong>ive D<strong>at</strong>a Systems Research (CIDR), Asilomar,<br />

CA, USA, January 2003.<br />

[10] Torsten Grust. Acceler<strong>at</strong>ing XP<strong>at</strong>h Loc<strong>at</strong>ion Steps. In<br />

Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 2002 <strong>ACM</strong> SIGMOD Int’l Conference on<br />

Management of D<strong>at</strong>a, Madison, WI, USA, June 2002.<br />

[11] Torsten Grust, Jan Rittinger, Sherif Sakr, and Jens<br />

Teubner. A SQL:1999 Code Gener<strong>at</strong>or for <strong>the</strong><br />

P<strong>at</strong>hfinder XQuery Compiler. In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 2007<br />

<strong>ACM</strong> SIGMOD Int’l Conference on Management of<br />

D<strong>at</strong>a, Beijing, China, June 2007.<br />

[12] Torsten Grust, Sherif Sakr, and Jens Teubner. XQuery<br />

on SQL Hosts. In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 30th Int’l Conference<br />

on Very Large D<strong>at</strong>abases (VLDB), Toronto, Canada,<br />

September 2004.<br />

[13] Torsten Grust, Maurice van Keulen, and Jens<br />

Teubner. Staircase Join: Teach a Rel<strong>at</strong>ional DBMS to<br />

W<strong>at</strong>ch its (Axis) Steps. In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 29th Int’l<br />

Conference on Very Large D<strong>at</strong>abases (VLDB), Berlin,<br />

Germany, September 2003.

[14] Haifeng Jiang, Hongjun Lu, Wei Wang, and<br />

Beng Chin Ooi. XR-Tree: Indexing XML D<strong>at</strong>a for<br />

Efficient Structural Joins. In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 19th Int’l<br />

Conference on D<strong>at</strong>a Engineering (ICDE), Bangalore,<br />

India, March 2003.<br />

[15] Quanzhong Li and Bongki Moon. Indexing and<br />

Querying XML D<strong>at</strong>a for Regular P<strong>at</strong>h Expressions. In<br />

Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 27th Int’l Conference on Very Large<br />

D<strong>at</strong>abases (VLDB), Rome, Italy, September 2001.<br />

[16] Jason McHugh and Jennifer Widom. Query<br />

Optimiz<strong>at</strong>ion for XML. In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 25th Int’l<br />

Conference on Very Large D<strong>at</strong>abases (VLDB),<br />

Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, September 1999.<br />

[17] Microsoft Corpor<strong>at</strong>ion. SQL Server 2005, 2005.<br />

[18] P<strong>at</strong>rick E. O’Neil, Elizabeth J. O’Neil, Shankar Pal,<br />

Istvan Cseri, Gideon Schaller, and Nigel Westbury.<br />

ORDPATHs: Insert-Friendly XML Node Labels. In<br />

Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 2004 <strong>ACM</strong> SIGMOD Int’l Conference on<br />

Management of D<strong>at</strong>a, Paris, France, June 2004.<br />

[19] Shankar Pal, Istvan Cseri, Oliver Seeliger, Gideon<br />

Schaller, Leo Giakoumakis, and Vasili Zolotov.<br />

Indexing XML D<strong>at</strong>a Stored in a Rel<strong>at</strong>ional D<strong>at</strong>abase.<br />

In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 30th Int’l Conference on Very Large<br />

D<strong>at</strong>abases (VLDB), Toronto, Canada, September<br />

2004.<br />

[20] Albrecht Schmidt, Martin L. Kersten, Menzo<br />

Windhouwer, and Florian Waas. Efficient Rel<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

957<br />

Storage and Retrieval of XML Documents. In The<br />

World Wide Web and D<strong>at</strong>abases (WebDB), 3rd Int’l<br />

Workshop, Dallas, TX, USA, May 2000.<br />

[21] Albrecht Schmidt, Florian Waas, Martin L. Kersten,<br />

Michael J. C<strong>are</strong>y, Ioana Manolescu, and Ralph Busse.<br />

XMark: A Benchmark for XML D<strong>at</strong>a Management. In<br />

Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 28th Int’l Conference on Very Large<br />

D<strong>at</strong>abases (VLDB), Hong Kong, China, August 2002.<br />

[22] Jayavel Shanmugasundaram, Kristin Tufte, Chun<br />

Zhang, Gang He, David J. DeWitt, and Jeffrey F.<br />

Naughton. Rel<strong>at</strong>ional D<strong>at</strong>abases for Querying XML<br />

Documents: Limit<strong>at</strong>ions and Opportunities. In Proc.<br />

of <strong>the</strong> 25th Int’l Conference on Very Large D<strong>at</strong>abases<br />

(VLDB), Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, September 1999.<br />

Morgan Kaufmann.<br />

[23] Igor T<strong>at</strong>arinov, Str<strong>at</strong>is D. Viglas, Kevin Beyer,<br />

Jayavel Shanmugasundaram, Eugene Shekita, and<br />

Chun Zhang. Storing and Querying Ordered XML<br />

Using a Rel<strong>at</strong>ional D<strong>at</strong>abase System. In Proc. of <strong>the</strong><br />

2002 <strong>ACM</strong> SIGMOD Int’l Conference on Management<br />

of D<strong>at</strong>a, Madison, WI, USA, 2002.<br />

[24] Chun Zhang, Jeffrey Naughton, David DeWitt, Qiong<br />

Luo, and Guy Lohman. On Supporting Containment<br />

Queries in Rel<strong>at</strong>ional D<strong>at</strong>abase Management Systems.<br />

In Proc. of <strong>the</strong> 2001 <strong>ACM</strong> SIGMOD Int’l Conference<br />

on Management of D<strong>at</strong>a, Santa Barbara, CA, USA,<br />

2001.