Colonial Queensland Chalon Head 1882 - Australia Post

Colonial Queensland Chalon Head 1882 - Australia Post

Colonial Queensland Chalon Head 1882 - Australia Post

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ARCHIVAL SNAPSHOTS<br />

> From the National Philatelic Collection<br />

<strong>Colonial</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong><br />

<strong>Chalon</strong> <strong>Head</strong> <strong>1882</strong><br />

5/- Rose<br />

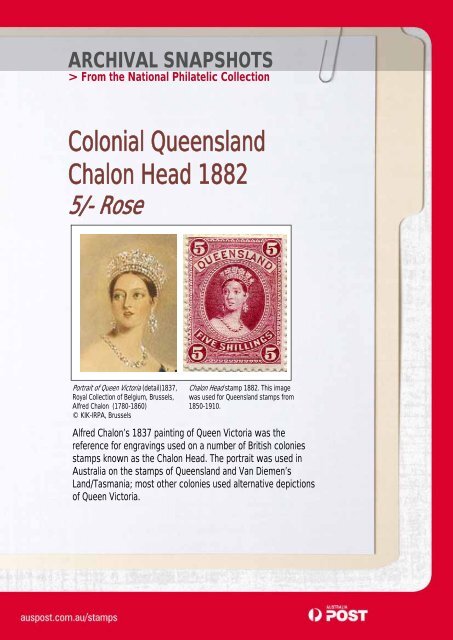

Portrait of Queen Victoria (detail)1837,<br />

Royal Collection of Belgium, Brussels,<br />

Alfred <strong>Chalon</strong> (1780-1860)<br />

© KIK-IRPA, Brussels<br />

<strong>Chalon</strong> <strong>Head</strong> stamp <strong>1882</strong>. This image<br />

was used for <strong>Queensland</strong> stamps from<br />

1850-1910.<br />

Alfred <strong>Chalon</strong>’s 1837 painting of Queen Victoria was the<br />

reference for engravings used on a number of British colonies<br />

stamps known as the <strong>Chalon</strong> <strong>Head</strong>. The portrait was used in<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> on the stamps of <strong>Queensland</strong> and Van Diemen’s<br />

Land/Tasmania; most other colonies used alternative depictions<br />

of Queen Victoria.

ARCHIVAL SNAPSHOTS<br />

> From the National Philatelic Collection<br />

Portrait of Queen Victoria, 1837, Alfred <strong>Chalon</strong>, Royal Collection of Belgium, © KIK-IRPA, Brussels<br />

Original Portrait<br />

The portrait head of Queen Victoria came from a painting by Alfred Edward<br />

<strong>Chalon</strong>, inspired by the first public appearance of Victoria as Queen on the<br />

occasion of her speech at the House of Lords where she opened the<br />

Parliament of the United Kingdom in July 1837. <strong>Chalon</strong>'s work was<br />

intended as a gift from Victoria to her mother. In the portrait she is<br />

wearing the George IV State Diadem, created in 1820, and the State<br />

Robes, a dress and a long royal mantle. Her body is half-turned to the right<br />

side, on top of a flight of stairs. While her head is turned to the right, her<br />

left hand holds the plinth of a column on which there is a sculpted lion. At<br />

that time, this portrait was also known as the "Coronation portrait" and an<br />

engraving by Samuel Cousins was distributed to the public on 28 June,<br />

1838.

ARCHIVAL SNAPSHOTS<br />

> From the National Philatelic Collection<br />

The Artist<br />

Alfred <strong>Chalon</strong> 1780-1860 RA<br />

<strong>Chalon</strong> was born in Geneva, Switzerland but left as a result of troubles<br />

arising from the French Revolution. The family eventually settled in London<br />

where Alfred and his brother John both became students at the Royal<br />

Academy. He was made a full Academician in 1816 and became known<br />

for painting miniatures on ivory. He also painted small portraits in<br />

watercolour on paper, often about 15 inches high. He was a witty<br />

caricaturist, and also painted genre and history subjects. His elegant<br />

miniatures and watercolour portraits were hugely fashionable. He was<br />

especially popular in court circles and was appointed painter in<br />

watercolour to Queen Victoria. He famously said when asked by the Queen<br />

whether he was worried by competition from the new invention of<br />

photography, “Ah non, Madame, photography can’t flatter!”. The portrait<br />

head of Queen Victoria came from a painting by Alfred Edward <strong>Chalon</strong>,<br />

inspired by the first public appearance of Victoria as Queen on the<br />

occasion of her speech at the House of Lords where she opened the<br />

Parliament of the United Kingdom in July 1837.<br />

Tasmania (Van Diemen’s Land) <strong>Chalon</strong> <strong>Head</strong> – Imperforate<br />

1d red, 2s green, 4d blue, 6d purple, 1/- orange

ARCHIVAL SNAPSHOTS<br />

> From the National Philatelic Collection<br />

Queen Victoria, portraiture and <strong>Australia</strong>n stamps<br />

Young Queen<br />

Pencil sketch for New<br />

South Wales ‘Diadems’<br />

c1851<br />

No sovereign had her image<br />

reproduced more often than Queen<br />

Victoria. Depictions appeared on<br />

medals, shaving cups, gongs, napkin<br />

rings, cufflinks, inkwells, paperclips,<br />

pipes, tea towels, pot lids, coins,<br />

postage stamps and also on<br />

Canadian canoes and <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

.<br />

prison ships.<br />

Victoria enjoyed many portraits<br />

made of her throughout her lifetime,<br />

portraits she often commissioned as<br />

family gifts or records for the public.<br />

Over the decades her image altered<br />

from innocent princess and young<br />

Queen to wife, mother, widowed<br />

matriarch and moral guardian of the<br />

country.<br />

‘Diadems’ 1854-1860<br />

New south Wales

ARCHIVAL SNAPSHOTS<br />

> From the National Philatelic Collection<br />

Queen Victoria 1838<br />

Alfred <strong>Chalon</strong> (1780-1860) ©<br />

National Portrait Gallery, Scotland<br />

Queen Victoria 1843<br />

Franz Xavier Winterhalter<br />

(1805-1873) German<br />

painter and lithographer<br />

The Royal Collection ©<br />

2010, Her Majesty Queen<br />

Elizabeth II<br />

Self-portrait, (detail)<br />

Queen Victoria aged 25<br />

1844 The Royal Collection<br />

© 2010, Her Majesty<br />

Queen Elizabeth II<br />

Domestic<br />

This watercolour by <strong>Chalon</strong> was<br />

the very first portrait the young<br />

queen sat for after her accession to<br />

the throne. She is dressed in the<br />

robes she wore when Parliament<br />

was dissolved after her uncle’s<br />

death. Her hat is casually discarded<br />

on the floor, she wears a<br />

decorative apron which gives a<br />

more domestic focus to this and<br />

other portraits produced during the<br />

middle period of her reign.<br />

Feminine<br />

Queen Victoria commissioned Franz<br />

Winterhalter to paint this romantic,<br />

and quite intimate portrait of her as<br />

a gift to her husband Prince Albert<br />

of Saxe-Coburg Gotha on his 24 th<br />

birthday. The oval frame, soft face,<br />

loose hair and bare shoulders show<br />

a more feminine figure.<br />

Sovereign<br />

Victoria’s sketch self-portrait<br />

shows a reflected gaze which is<br />

without hesitation as to its owner’s<br />

character as well as her sense of<br />

sovereign purpose

ARCHIVAL SNAPSHOTS<br />

> From the National Philatelic Collection<br />

Queen Enthroned<br />

State portrait of Queen Victoria<br />

Sir George Hayter, oil on canvas,<br />

(1838) National Portrait Gallery.<br />

Photographic reproduction in<br />

National Philatelic Collection<br />

(Detail from portrait) ©<br />

National Portrait Gallery<br />

London<br />

Queen on Throne stamp<br />

(reprint) (Coronation<br />

Throne) 1852-54<br />

Engraving after Sir<br />

George Hayter’s State<br />

Portrait<br />

Sir George Hayter was the Queen’s<br />

“Portrait and Historical Painter” and<br />

in 1841 was made “Principal<br />

Painter in Ordinary to the Queen”.<br />

He painted several royal<br />

ceremonies including Queen<br />

Victoria’s coronation of 1837 and<br />

marriage of 1840 and also the<br />

christening of the Prince of Wales<br />

of 1843. He also painted several<br />

royal portraits including his most<br />

well known work, the State Portrait<br />

of the new Queen Victoria. Several<br />

versions of this portrait were done,<br />

to be sent as diplomatic gifts.<br />

Hayter's active period at court was<br />

short-lived because Prince Albert<br />

preferred German painters. By the<br />

mid-1840s Hayter’s portrait style<br />

was considered old-fashioned. He<br />

adjusted his type of history painting<br />

to suit the more literal taste of the<br />

early Victorian era. Although a very<br />

simplified interpretation, the fulllength<br />

Queen on Throne stamp<br />

captures the early Victorian gothic<br />

style with the pointed design of the<br />

Coronation Throne and in the<br />

decorative elements and<br />

background borders of the<br />

engraved stamp.

ARCHIVAL SNAPSHOTS<br />

> From the National Philatelic Collection<br />

Widowed matriarch<br />

Queen Victoria ,<br />

Photographer, Alexander<br />

Bassano 1885<br />

National Portrait Gallery,<br />

London<br />

Commemorative<br />

Diamond Jubilee<br />

Canada 5c<br />

Queen Victoria,<br />

Diamond Jubilee 1897<br />

Photography W & D<br />

Downey ©<br />

National Portrait Gallery,<br />

London<br />

Definitive stamps<br />

1897-1910 2d, 21/2d<br />

New South Wales<br />

Victoria’s interest in portraiture reflected the Victorian interest in<br />

realism influenced by the development of photography which was of<br />

great interest to the Queen. She kept photographic albums, attended<br />

photographic exhibitions and fervently supplied her portraitists with<br />

photographs of their subject for reference. Images of Victoria that<br />

appeared on stamps were based on engravings or lithographs derived<br />

from either photography, paintings or watercolours.

ARCHIVAL SNAPSHOTS<br />

> From the National Philatelic Collection<br />

Queen Victoria as guardian and embodiment of the<br />

Empire<br />

Portrait of Queen Victoria,<br />

(detail) Photographer<br />

Alexander Bassano ©<br />

National Portrait Gallery,<br />

London<br />

Patriotic Fund,<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong><br />

1900<br />

Patriotic Fund,<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong><br />

1900<br />

There had been general criticism of portraits of Queen Victoria as lacking in<br />

vitality and being unsmiling but it was also known that Queen Victoria used<br />

portraiture to hide her smile and emphasise her serious image as a sovereign.<br />

After Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert passed away in 1861, the Queen<br />

went into a very long period of seclusion and withdrawal from public life which<br />

lasted almost 10 years (1861-1871). It said that she needed to reassert her<br />

claim to the monarchy and did so through portraits representing her as a<br />

powerful monarch hardened by personal grief and widowhood. Portraits of<br />

the 1870s show her as a resolute guardian and embodiment of English power.<br />

This later image of Victoria persisted until her death in 1901.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Portraits of the Queen Ira B Nadel, Victorian Poetry, Vol.25, No. 3/4 , Centennial of Queen Victoria’s golden<br />

Jubilee (Autumn-Winter, 1987), pp.169-191, West Virginia University Press