The Road Less Travelled - Emily Chantiri

The Road Less Travelled - Emily Chantiri

The Road Less Travelled - Emily Chantiri

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

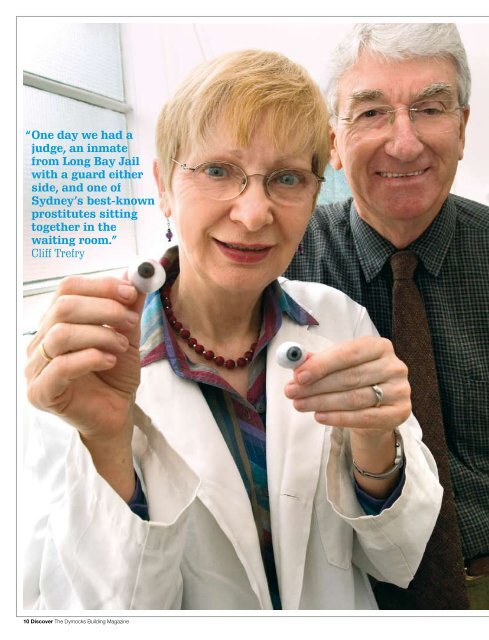

“ One day we had a<br />

judge, an inmate<br />

from Long Bay Jail<br />

with a guard either<br />

side, and one of<br />

Sydney’s best-known<br />

prostitutes sitting<br />

together in the<br />

waiting room.”<br />

Cliff Trefry<br />

10 Discover <strong>The</strong> Dymocks Building Magazine

Still dreaming about pursuing your<br />

life’s purpose? <strong>Emily</strong> <strong>Chantiri</strong><br />

meets three people who chose<br />

unusual career paths – and never<br />

looked back.<br />

One of the more unusual requests came from<br />

Australian artist Brett Whiteley who wanted<br />

a fake eye for a painting he was working on.<br />

A theatre company also ordered a perfectly<br />

round eye to roll around the stage of their<br />

latest play.<br />

It has been said that if you follow your passion then you will never work a<br />

day in your life. <strong>The</strong> stories you’re about to read are from three people who<br />

have done just that. Not satisfied with the run-of-mill-type professions, they<br />

decided to follow their calling and have never looked back.<br />

Bright Eyes<br />

In 1949, industrial engineer Cliff Trefry’s career took a dramatic turn after he<br />

lost an eye in a workplace accident. At the time, there were only two artificial<br />

eye makers in New South Wales; one was Les Taylor who Trefry visited<br />

regularly to have his new eye custom-made. A strong bond formed between<br />

the men and Trefry found he was increasingly more interested in how artificial<br />

eyes were made than in his own profession of engineering. Before long, he<br />

was training under Taylor and then off to London on a scholarship to further<br />

hone his newfound craft. Now, he and business partner Edit Gillott run<br />

Taylor&Trefry, artificial eye manufacturers.<br />

Contrary to what you might expect, these two do not make for a solemn<br />

pair. <strong>The</strong>y are jovial and brimming with humour and life. Gillott, a former<br />

schoolteacher, was asked to help out in her school holidays. Her skills with<br />

handling youngsters were invaluable to a business that sees a lot of children<br />

who have been born with only one eye or lost one in an accident. She loved<br />

the work so much that she never left.<br />

“It is so interesting and fascinating,” enthuses Gillott. “I really enjoy the<br />

clients and I still see many of them today. When you see someone come in<br />

with a slightly misshapen face, hoping for and wanting something better for<br />

themselves, you know that you can give them that. <strong>The</strong>y leave feeling better<br />

about themselves and you can’t help feeling better yourself as well,” says<br />

Gillott who confesses to getting a buzz out of perfecting the colour and shape<br />

of each eye to match the original.<br />

Both Trefry and Gillott agree that it is the people they meet who make the<br />

work so enjoyable. <strong>The</strong>y say that most of their clients seem to have a more<br />

pronounced sense of humour than sighted people and that makes them<br />

better company. One client who is completely blind spends his whole time<br />

making them laugh.<br />

Some requests have come from left field. Like when Australian artist Brett<br />

Whiteley walked into their small premises on the Dymocks Building’s fifth floor<br />

and requested an eye for one of his paintings. Another came from a theatre<br />

company that wanted an artificial eye to roll around on stage. “We had to<br />

make it perfectly round, so it rolled and rolled,” laughs Gillott.<br />

“It doesn’t matter what their social standing or wealth, our clients come<br />

from all walks of life,” adds Trefry. “One day in the waiting room there was a<br />

judge, an inmate from Long Bay Jail with a guard either side and across the<br />

other side of the room sat one of Sydney’s best-know prostitutes.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>y’ve seen their fair share of tragedies, too: babies who were born<br />

without eyes, blind children, cancer sufferers who lose half their face. <strong>The</strong><br />

artificial eyes are made from acrylic and carefully matched so that no-one can<br />

tell which is the good one. Trefry takes due pride in that.<br />

<strong>The</strong> eyes are free, subject to the Department of Health guidelines,<br />

and, generally speaking, a person with an ocular prothesis will require a<br />

replacement every four years.<br />

“You help people and you get paid for something that you really love<br />

doing,” beams Gillott. Trefry concurs: “<strong>The</strong> most rewarding part of my job is<br />

the friendships I’ve made. <strong>The</strong>y’re long-standing and genuine, it would be<br />

bloody hard to find anything better than this.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> Dymocks Building Magazine Discover 11

“ as soon as I walked in the door<br />

everything inside me went, ‘YES!<br />

This is it! ” Karen Workman<br />

“ I get so far into the job,<br />

in my mind I could be<br />

on a tropical island.”<br />

John W. Thompson<br />

Karen Workman says<br />

she has experienced<br />

‘miraculous’ moments in<br />

her work as a therapist.<br />

Go with the Flow<br />

Increasingly dissatisfied with her career in human resources, Karen<br />

Workman knew it was time for a change but didn’t know what that<br />

change should be. She left her job, packed her bags and went travelling<br />

to explore the world as much as her future options. She settled for a time<br />

in Canada when a chance meeting changed the course of her life. She<br />

was attending a workshop about passion in life when she met a woman<br />

who had been studying Reiki. This complete stranger ardently insisted<br />

Workman join her for a class. Following a hunch, she agreed.<br />

“It was a freezing cold night,” recalls Karen Workman, “but as soon<br />

as I walked in the door and into the class, everything inside me went,<br />

‘YES! This is it! I am home’. I began to study and practice passionately,<br />

giving Reiki to anyone I could get my hands on.”<br />

Shortly after, she returned home to Australia and set up her own<br />

practice. Six months later she was reading an article on Hakomi<br />

therapy when she felt a familiar pull. “When I read about Hakomi I was<br />

immediately energetically drawn to it,” she says. “<strong>The</strong>re is something in<br />

me that has always wondered about people more deeply. Talking about<br />

issues wasn’t the only way. I knew this through my own experience of<br />

therapy.”<br />

Hakomi is a therapy that involves using the body to explore<br />

and understand ourselves better. It is based on and committed to<br />

principles of mindfulness, non-violence, mind-body holism and unity.<br />

Karen Workman knew that this was the link she had been waiting for,<br />

connecting her passions for the mind, body and spirit. <strong>The</strong> initial flame<br />

that ignited her passion still burns strongly 20 years later.<br />

Karen Workman offers this advice for anyone looking to find their<br />

passion: “You can feel it in your system. It’s not cognitive. It’s is the fire<br />

in your belly that just keeps burning. When you can be mindful of those<br />

times in your life when you have felt like this, you can follow that path and<br />

it will lead to passion.”<br />

Today, Karen Workman believes that therapy isn’t about locating<br />

problems or searching for answers to why issues occur. She says<br />

therapy is about moving through the limitations that constrict our<br />

consciousness in order for us to feel our greatness, to know the inner<br />

truth of who we are, and to connect with our innate qualities such as love<br />

and happiness.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re have been so many rewarding moments “even miraculous<br />

ones,” she says. “One man suffered incredible panic attacks, which were<br />

brought on by his fear of flying. This was stopping him from visiting his<br />

girlfriend in Ireland. After six months of therapy, I received a message on<br />

my answer machine. He was calling from Heathrow airport in London. He<br />

had done it! I felt a thrill of real joy for him.”<br />

12 Discover <strong>The</strong> Dymocks Building Magazine

John W. Thompson’s services have been<br />

requested by Buckingham Palace, where<br />

he has hand-engraved invitations for Her<br />

Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.<br />

Lord of the Ring<br />

John W. Thompson didn’t have to search far to find out why he<br />

has a passion for rings – his ancestors have been designing them<br />

for the British royal family for centuries.<br />

Growing up in London’s East End in the 1960s, Thompson<br />

decided he wanted to be a diamond mounter (commonly known<br />

as a jeweller). “To be honest I hated the course until I picked up<br />

the engraving chisel,” admits Thompson. “From the very first<br />

moment I picked up that graver, I was hooked. I knew this is<br />

was what I wanted to do, it was as if I was being pulled in that<br />

direction.” He was surprised to discover that engraving was in his<br />

blood, tracing his passion back to his ancestor William Hogarth, a<br />

famous 18th century English engraver to the Royal family.<br />

To support himself while studying, Thompson worked at<br />

a tractor plant where, during the long hours he dreamed of<br />

becoming a master hand-engraver. Luck was on his side, as<br />

the firm William Day of London took him on to serve a five-year<br />

apprenticeship. He was to be the last engraver’s apprentice to be<br />

taken on anywhere in the United Kingdom.<br />

Thompson moved to Australia in the 1980s and still uses<br />

traditional engraving methods passed down from the Middle Ages,<br />

boasting that he is fast-becoming a dinosaur. His pieces include<br />

seal and signet rings, cufflinks, pendants and bangles made from<br />

gold, platinum and sterling silver. He engraves decorative patterns<br />

dating back to the 18th century, including phrases and sayings in<br />

languages from Hebrew to Gaelic to Chinese.<br />

Thompson’s reputation as a master engraver is known<br />

around the world. His clients hail from Hollywood to Buckingham<br />

Palace and include former prime ministers and current media<br />

moguls. Thompson designed the signet ring for Prince Charles<br />

when he became the Prince of Wales and recently completed<br />

another for royalty of a different kind: Australian racing identity<br />

Gai Waterhouse.<br />

He likens his job to yoga. “My work is relaxing,” he reveals. “I<br />

get so far into the job, in my mind I could be on a tropical island.”<br />

At 59 years of age, Thompson has no plans of retiring. His son<br />

Peter works alongside him inheriting the traditional ways. “If Dad<br />

retires, I’ll have him come in on a casual basis,” jokes Peter, “Just<br />

six days a week!”<br />

Thompson, a warm man with a quick wit, shuns the title<br />

master engraver and prefers to call himself an artisan, a man<br />

continually crafting his work. According to his wife Linda, his<br />

passion is so consuming that even she cannot compete with his<br />

love of his craft. “It’s 24 hours, seven days. John eats, drinks,<br />

sleeps his job,” she says.<br />

“My job is never boring, I receive immense satisfaction from<br />

my clients,” he says. “Recently I made some cufflinks for a woman<br />

whose son was turning 21 years old. When she saw the cufflinks<br />

she burst into tears. Her joy was overwhelming. I feel very lucky<br />

to have a career I love; it has so many rewards. Every job I do is a<br />

special job and every one is different.” [D]<br />

<strong>The</strong> Dymocks Building Magazine Discover 13