PDF file (1.6 MB) - PalArch

PDF file (1.6 MB) - PalArch

PDF file (1.6 MB) - PalArch

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

In this special issue:<br />

The <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation’s Newsletter<br />

volume 1, no. 1 (April 2004)<br />

News on the activities of the <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 2<br />

Egypt in photographs (Z. Kosc) 4<br />

Telling science (P. Shipman ) 4<br />

The history of the Palaeontological-Mineralogical<br />

Cabinet of the Teylers Museum, Haarlem,<br />

The Netherlands (J.C. van Veen) 7<br />

The Natural Sciences Library of the Teylers<br />

Museum, Haarlem, The Netherlands<br />

(M. van Hoorn) 21<br />

Sex in the museum (V. van Vilsteren) 24<br />

Archaeological illustration; combining ‘old’ and<br />

new techniques (M.H. Kriek) 29<br />

The pleasure of travelling to the past (C. Papolio) 33<br />

The mammoths beneath the sea (D. Mol) 35<br />

‘Archeologie Magazine’ in the electronic age<br />

(L. Lichtenberg) 37<br />

Colophon 40<br />

Edited by A.J. Veldmeijer, S.M. van Roode & A.M. Hense<br />

© 2004 <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation<br />

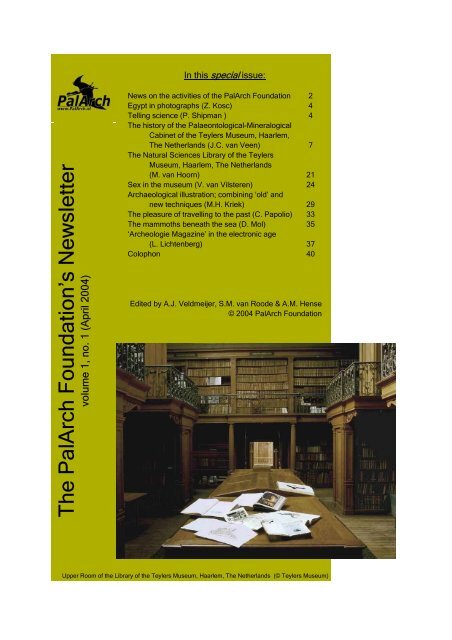

Upper Room of the Library of the Teylers Museum, Haarlem, The Netherlands (© Teylers Museum)

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

News on the activities of the <strong>PalArch</strong><br />

Foundation<br />

New Newsletter<br />

As promised, the new Newsletter is a<br />

fact. From now on it is not only meant to inform<br />

the members of the editorial and advisory<br />

boards on the activities of the Foundation, but<br />

to bring background information for them as<br />

well as for the supporters of the Foundation!<br />

We like to thank the contributors to this<br />

issue as well as the persons involved in<br />

checking English. Thanks also to Carlos<br />

Papolio for allowing us to use one of his works<br />

of arts as this issue’s watermark.<br />

The official release of the first issue of<br />

the Foundation’s magazine will be done by the<br />

Dutch minister of Education, Culture and<br />

Science (OCW) Mrs. M.J.A. van der Hoeven<br />

on 3 April (see invitation) and is celebrated<br />

with a small symposium called ‘Dinosaurs,<br />

mummies and river dunes’. An elaborate report<br />

will be included in the next Newsletter!<br />

Monograph<br />

The Foundation has developed ways to<br />

publish monographs in digital as well as analog<br />

formats, which do not differ from each other in<br />

layout. However, in order to keep the price of<br />

the analog as low as possible, the illustrations<br />

are included on a CD; in the text clear<br />

references will be made to the appropriate<br />

illustration. For more information, see<br />

http://www.palarch.nl/information.htm.<br />

Supporter<br />

It is possible to become supporter of the<br />

Foundation and support, financially and<br />

morally, the important work. This costs only<br />

EURO 10. As a supporter, you will be sent by<br />

email our Newsletter four times a year and you<br />

will have a discount of 10% on all <strong>PalArch</strong><br />

products and registration fees. For more<br />

details,<br />

visit<br />

http://www.palarch.nl/information.htm.<br />

First issue<br />

As mentioned previously, the first issue<br />

of www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl is a special one, in which<br />

the various members of the boards presents<br />

themselves by publishing a paper, book review<br />

or other contribution (see ‘Publications issue 1<br />

(April 2004)’). Due to busy schedules, some<br />

have not been able to meet the deadline, but<br />

promised to submit a contribution for the next<br />

issue (these are listed under the heading<br />

‘Forthcoming’). Not all of them are listed here,<br />

however. ‘#’ means that it was not yet known at<br />

the time of printing the Newsletter.<br />

Publications issue 1 (April 2004)<br />

Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology<br />

Harrell, J.A. 2004. Petrographic investigation of<br />

Coptic limestone sculptures and reliefs<br />

in the Brooklyn Museum of Art. –<br />

<strong>PalArch</strong>, series archaeology of<br />

Egypt/Egyptology 1, 1: 1-16.<br />

Andrews, C.A.R. 2004. An unusual inscribed<br />

amulet. - <strong>PalArch</strong>, series archaeology of<br />

Egypt/Egyptology 1, 2: 17-20.<br />

Verhoogt, A.M.F.W. 2004. Family relations in<br />

Early Roman Tebtunis. - <strong>PalArch</strong>, series<br />

archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 1, 3:<br />

21-25.<br />

Dieleman, J. 2004. Mysterious lands. By:<br />

O’Connor, D. & S. Quirke. Eds. 2003.<br />

(London, Cavendish Publishing Limited).<br />

- Book review, <strong>PalArch</strong>, non scientific.<br />

Roode, van, S.M. 2004. Never had the like<br />

occurred. Egypt’s view of it’s past. By:<br />

Tait, J. Ed. 2003. (London, Cavendish<br />

Publishing Limited). - Book review,<br />

<strong>PalArch</strong>, non scientific.<br />

Roode, van, S.M. 2004. Affairs and scandals in<br />

ancient Egypt. By: Vernus, P. 2003.<br />

(Ithaca/London, Cornell University<br />

Press). - Book review, <strong>PalArch</strong>, non<br />

scientific.<br />

Vertebrate palaeontology<br />

Everhart, M.J. 2004. Late Cretaceous<br />

interaction between predators and prey.<br />

Evidence of feeding by two species of<br />

shark on a mosasaur. – <strong>PalArch</strong>, series<br />

vertebrate palaeontology 1, 1: 1-7.<br />

Meijer, H.J.M. 2004. The first record of birds<br />

from Mill (The Netherlands). – <strong>PalArch</strong>,<br />

series vertebrate palaeontology 1, 2: 8-<br />

13.<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 2

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

Nieuwland, I.J.J. 2004. A taxonomical<br />

nightmare:<br />

Archaeopteryx,<br />

Griphosaurus, Archaeornis. – <strong>PalArch</strong>,<br />

series vertebrate palaeontology 1, 3: #-<br />

#.<br />

Veldmeijer, A.J. & A.M. Hense. 2004.<br />

Supplement to: Pterosaurs from the<br />

Lower Cretaceous of Brazil in the<br />

Stuttgart collection, in: Stuttgarter<br />

Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B<br />

(Geologie und Paläontologie) 2002, 327:<br />

1-27. – <strong>PalArch</strong>, series vertebrate<br />

palaeontology 1, 4: #-#<br />

Lambers, P.H. 2004. Missing links.<br />

Evolutionary concepts & transitions<br />

through time. By: Martin, R.A. 2003.<br />

(Sudbury, Jones and Bartlett<br />

Publishers). – Book review, <strong>PalArch</strong>, non<br />

scientific.<br />

Storm, P. 2004. Fossil frogs and toads of North<br />

America. By: Holman, J.A. 2003.<br />

(Bloomington, Indiana University Press).<br />

– Book review, <strong>PalArch</strong>, non scientific.<br />

Signore, M. Exploratory excavations and new<br />

insights on the palaeoenvironment of<br />

Pietraroja.<br />

Vos, de, J. Ice age cave faunas of North<br />

America. By: Schubert, B.W., J.I. Mead<br />

& R.W. Graham. Eds. 2003.<br />

(Bloomington, Indiana University Press).<br />

– Book reviews, <strong>PalArch</strong>, non-scientific.<br />

Archaeology of North West Europe<br />

Veldmeijer, A.J. 2004. Return to Chauvet cave.<br />

Excavating the birthplace of art. The first<br />

full report. By: Clottes, J. Ed. 2003.<br />

(London, Thames & Hudson). – Book<br />

review, <strong>PalArch</strong>, non scientific.<br />

Forthcoming<br />

Clapham, A.J. Greek fire, poison arrows &<br />

scorpion bombs. Biological and chemical<br />

warfare in the ancient world. By: A.<br />

Mayor. 2003. (Woodstock/New<br />

York/London, The Overlook Press). –<br />

Book review, <strong>PalArch</strong>, non scientific.<br />

Hoek Ostende, van den, L.W. & W. Kakebeke.<br />

Results from the field campagnes in the<br />

Tegelen Clay (1970-1977).<br />

Nicholson, P.T. et al. [conservation of bronzes]<br />

Nieuwland, I.J.J. 2004. African dinosaurs<br />

unearthed. The Tendaguru expeditions.<br />

By: G. Maier. 2003. (Bloomington,<br />

Indiana University Press). – Book<br />

reviews, <strong>PalArch</strong>, non-scientific.<br />

Rose, P.J. Ancient Egypt in Africa. By:<br />

O’Connor, D. & A. Reid. Eds. 2003.<br />

London, Cavendish Publishing Limited).<br />

– Book review, <strong>PalArch</strong>, non scientific.<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 3

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

Egypt in photographs<br />

By Z. Kosc<br />

Ababda Bedouins are driving their goats to where it is common and lopping off branches of acacia for<br />

them, both leaves and young pods being eaten. Wadi Gemal , Eastern Desert, Egypt. Photography Z.<br />

Kosc © 2004 (See too: http://puck.wolmail.nl/~kosc/Ababda folder/ababda.html).<br />

Acacia Sayali<br />

According to some Biblical scholars, the acacia tree is mentioned in the Bible (I will plant<br />

in the<br />

wilderness... the Shittah tree. Isaiah 41), some even speculate that it was only natural that Moses<br />

should turn to acacia when he came to build the Ark of the Covenant and the Tabernacle and needed<br />

beams and timber. The ancient Egyptians made coffins, some still intact, from the wood. The leaves<br />

are important for forage and the wood for fuel where the trees are abundant. In the folk medicine the<br />

gum is believed to be aphrodisiac, but is also is supposed to afford some protection against bronchitis<br />

and rheumatism.<br />

affects all of our lives. I want to root my stories<br />

in my readers' and listeners' minds so deeply<br />

Telling science<br />

that science will flourish there is perpetuity. To<br />

me, science is more than a body of knowledge,<br />

By P. Shipman<br />

it is a way of thinking. Born of curiosity,<br />

nourished by discovery, science is a<br />

It is my great pleasure to write this essay marvellous way of finding things out, of making<br />

for the opening edition of the <strong>PalArch</strong> sense of the world. Now, early in the 21 st<br />

Foundation’s Newsletter because the purpose century, I am ever more convinced that the<br />

of this organization and its innovative journal language of science is one in which we must<br />

are close to my heart. I am one of those all become fluent.<br />

scientists who double as a science writer: that<br />

One of the main reasons I think telling<br />

is, one who writes science for non-scientists as science is so vital comes from my research<br />

well as for fellow scientists. I am deeply background in human evolution. Since the<br />

convinced that the ready dissemination of evolutionary origin of the human species, our<br />

science to the broader public is not only an survival and well-being has depended upon<br />

intellectual duty but also a moral one. This new our abilities to observe, to analyse, to<br />

journal promises to be a venue that will synthesize, and to remember information about<br />

encourage and promote telling science.<br />

the world around us. Science is a way of doing<br />

What is telling science? Telling science that.<br />

is the same as telling a story, except the<br />

One of the capacities for handling<br />

subject is a fundamentally important story that information that marks modern humans is<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 4

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

language. Full, human language is an ability to<br />

encode, decode, and share information that<br />

goes well beyond the often-remarkable<br />

capabilities of non-human animals to<br />

communicate. Language is symbolic action.<br />

Language is abstract; it is structured and it<br />

possesses a class of words known as<br />

disambiguators that makes the crucial<br />

distinction between ‘I bite the tiger’ and ‘the<br />

tiger bites me.’ Language includes the<br />

important abilities to promise, cajole, threaten,<br />

and paint imaginary scenarios. Language is<br />

also an intrinsically social ability that involves<br />

more than one person. Infants and children<br />

who are, for some grotesque reason, deprived<br />

of human companionship during a crucial<br />

period of their development do not acquire any<br />

semblance of full language even if they are<br />

later rescued and taken into normal conditions.<br />

Apparently, language cannot or does not<br />

develop without the stimulation of someone to<br />

talk to and with during a key period of brain<br />

development. Language is not, then, simply a<br />

collection of sounds or gestures with symbolic<br />

meaning and rules for ordering those sounds<br />

or gestures. Instead, language is an intricate<br />

series of brain functions that are involved in<br />

observing and storing thoughts and<br />

information, translating them into symbols, and<br />

being able to transmit them to another person,<br />

whether or not that person shares the<br />

experience or observation. The particular form<br />

that any specific language takes is as variable<br />

as human beings themselves.<br />

Science is a sort of intellectual dialect,<br />

not a true language in and of itself. Like any<br />

living language, science is always changing<br />

and evolving, which may cause discomfort to<br />

the old-fashioned who adhere rigidly to rules.<br />

Three crucial questions mark the mind of a<br />

scientific thinker.<br />

-- What do you know?<br />

-- How do you know that?<br />

-- What would change your mind?<br />

I believe science offers us ways to seek<br />

and gain understanding, which are profoundly<br />

important aims. When I tell science, I am<br />

seeking both to impart information and to teach<br />

others how to ‘think’ science. It is a truism, and<br />

even a truth, that any single piece of scientific<br />

knowledge is subject to revision after more<br />

evidence is gathered. Some use this premise<br />

to argue that learning scientific ‘facts’ is<br />

therefore a waste of time, since they are all<br />

uncertain and will change eventually. I<br />

disagree. There is a huge body of knowledge<br />

so well supported, so thoroughly confirmed by<br />

observations in numerous spheres, that it can<br />

be accepted as true. Our airplanes fly because<br />

of it; our light bulbs light; and, whether we<br />

understand all the details or not, our chickens<br />

lay eggs; our musicians exercise their vocal<br />

cords and sing. The problem is simply that<br />

reality is a wonderful and terrible and<br />

complicated thing and we are not always smart<br />

enough to grasp all its nuances at once. It is<br />

wiser to allow for revision in case reality<br />

becomes a little clearer in the future.<br />

He or she who would write science takes<br />

on a dual charge: to communicate scientific<br />

knowledge and to show how science is done,<br />

thus infecting the reader with the virus of<br />

scientific thinking. There are many justifications<br />

for this charge. One of them is that it is a duty.<br />

A discovery unshared is lost. And if public<br />

funds are used to further the discovery, then<br />

certainly there is a moral obligation on the part<br />

of those who accept the funding to transmit<br />

their findings to the public. If science is able to<br />

improve our world, either by making sense of<br />

things or by allowing us to alter reality, then<br />

science, like language, must be shared.<br />

There is also a danger to exclusive,<br />

hidden science. From the sinister medieval<br />

alchemist, to the witch brewing her potions and<br />

spells, to the mad scientist of the cinema, our<br />

culture is replete with images of those who<br />

hoard arcane knowledge and use it for their<br />

own selfish means. People dislike and distrust<br />

the possessors of powerful and secret<br />

knowledge, with good reason. How are we as<br />

scientists to quell or forestall that resentment<br />

and suspicion? By telling science, of course.<br />

Unfortunately, doing science often<br />

requires developing an esoteric vocabulary,<br />

learning incomprehensible procedures,<br />

mastering Byzantine mathematical techniques,<br />

and memorizing obscure acronyms. These are<br />

all ways of concealing science, of shutting the<br />

public out and keeping the precious<br />

information for us, the scientists. Of course, if<br />

scientists talk and think about ideas or entities<br />

outside of the common experience, they must<br />

invent new language. But there is no reason<br />

that jargon must go unexplained, on the<br />

contrary, it should not. The jargon itself is a<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 5

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

moat, the abstruse concepts a wall that<br />

together keep the public from storming the<br />

gates and taking possession of scientific<br />

knowledge and practice. This is exactly the<br />

opposite of what I would advocate.<br />

I maintain that the deliberate failure to<br />

explain scientific jargon, principles, and<br />

discoveries to the general public is downright<br />

wicked. The failure arises, I think, from a fatal<br />

combination of arrogance and laziness, in the<br />

presence of an unfortunate lack of empathy.<br />

There is nothing I resent so fiercely as<br />

someone who says, "It is too complicated for<br />

you to understand; trust me."<br />

I also think that concealing science and<br />

making it exclusive are ultimately hostile to the<br />

aims of science itself. Why do scientists do<br />

science? Because science is fun, science is<br />

cool, science is ‘about’ discovery. Who would<br />

not want to share that with everyone who will<br />

listen? Only those who need a secret password<br />

to prove their own cleverness.<br />

How many feel the need for such<br />

exclusiveness has become patently clear in<br />

recent months, when protests have been heard<br />

against the nomination of Susan Greenfield, a<br />

professor of neuroscience at Oxford University,<br />

to be a Fellow of the Royal Society in the<br />

grounds that she has often appeared on<br />

television and in non-scientific publications as<br />

an explainer of science. Her response to the<br />

criticism is one I heartily endorse (MacLeod,<br />

2004): “When it comes to engaging with the<br />

public, many scientists would argue that they<br />

do not have the time, the experience or,<br />

indeed, the motivation to give talks to the great<br />

unwashed. After all, it is no small feat to take<br />

your life's work and passion and strip it of all<br />

technical terminology and jargon to make it<br />

accessible. It involves ignoring the peerrevered<br />

trees to reveal the entire wood to a<br />

general audience in a clear, accurate and<br />

appealing way. Small wonder that, until now,<br />

such endeavours have been left to a small<br />

minority of media-hungry... apostates who, in<br />

the eyes of many 'normal' members of the<br />

white-coat community, are marginalized as<br />

'real' scientists.”<br />

It is time for ‘real’ scientists to accept<br />

their responsibility for learning to communicate<br />

their work clearly and intelligently, and for the<br />

scientific community to stop denigrating the<br />

value of this difficult and essential endeavour.<br />

If science is to be communicated, as I<br />

believe it must, then how is it to be done? We<br />

have all heard the words of scientists who think<br />

they are communicating when in fact they are<br />

speaking gibberish. They jabber away at us,<br />

sighing wearily at the public's hopeless<br />

ignorance and stupidity when we misconstrue<br />

the few words and phrases we can recognize<br />

out of the impenetrable jungle of nonsense.<br />

These scientists have their hearts in the right<br />

place but their heads in the wrong one. They<br />

once learned this special language, this<br />

framework of theories and techniques, and so<br />

can the general public.<br />

What is needed is transparency:<br />

language that is so clear that it lets in the light<br />

without our ever noticing its presence. How is<br />

this to be achieved? Good will is not enough;<br />

good sense must direct it. Those who write<br />

science must start from a common frame of<br />

reference, by beginning the story where we all<br />

stand on the same ground.<br />

There is considerably art and talent<br />

involved in finding that common ground but it is<br />

there for those who seek it. One of the first<br />

steps that must be taken, one that is being<br />

taken by the <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation, is<br />

legitimising and encouraging those who try to<br />

communicate broadly and reach a bigger<br />

audience. Another is to invest in a technique of<br />

story-telling so simple and so powerful that it is<br />

explained in the children's book Alice's<br />

Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll<br />

(Charles Dodgson): "Begin at the beginning...<br />

and go on till you come to the end: then stop."<br />

Cited literature<br />

MacLeod, D. 2004. Royal Society split over<br />

Greenfield fellowship. - The Guardian<br />

(Feb. 6.).<br />

Pat Shipman<br />

Pennsylvania State University<br />

University Park<br />

PA 16802 USA<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 6

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

The history of the Palaeontological-<br />

Mineralogical Cabinet of the Teylers Museum,<br />

Haarlem, The Netherlands<br />

By J.C. van Veen<br />

Introduction<br />

In Haarlem, a town in the neighbourhood<br />

of Amsterdam in The Netherlands, you will find<br />

on the bank of the river Spaarne, a museum<br />

with a bronze statue on its roof. The statue is a<br />

huge angel who presents two laurel wreaths;<br />

one to a figure with a painter’s brush and a<br />

palette and one to a figure with a book. The<br />

three are the symbols for fame, art and<br />

science.<br />

seems to overshadow the rest of the museum<br />

such as the paintings (mostly from romantic<br />

painters and from the Hague School), the<br />

beautiful library with its magnificent books, the<br />

Cabinet of Science with its copper and wooden<br />

scientific instruments, the Numismatic Cabinet<br />

with its medals and coins and also the<br />

Palaeontological-Mineralogical Cabinet with its<br />

fossils, minerals, crystals and rocks. However,<br />

the drawings are mostly hidden in safes and<br />

stockrooms, whereas the large number of<br />

fossils, crystals, coins, instruments and<br />

paintings, can be admired in their 18 th and 19 th<br />

centuries, handmade furniture and showcases.<br />

The museum is called ‘The Museum of<br />

the Museums’, because of its preserved<br />

exhibitions in their original 18 th and 19 th<br />

centuries state. The recent 20 th century<br />

buildings are, fortunately, not disturbing the<br />

atmosphere of old buildings; on the contrary,<br />

they emphasize the old style.<br />

The founder and his Foundation<br />

Pieter Teyler van der Hulst, a rich<br />

manufacturer of textiles, died in 1778 without<br />

heirs. In his Will he founded the Teylers<br />

Foundation (Teylers Stichting). Five friends of<br />

his were appointed to be the directors of this<br />

foundation. He also formulated the objectives<br />

of his Foundation:<br />

The front of the museum at the Spaarne<br />

riverside (© Teylers Museum).<br />

The museum in question, the Teylers<br />

Museum, is most famous for its art and<br />

especially the drawings, which include works of<br />

Michelangelo (20 specimens) and Rafaël (16).<br />

The complete collection consists of more than<br />

1600 Italian works and many more old Dutch<br />

(including all etchings of Rembrandt) and<br />

French drawings. This wealth of drawings<br />

Pieter Teyler van der Hulst (1702-1778)<br />

(© Teylers Museum).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 7

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

1. Support the poor<br />

2. Promote liberal theology<br />

3. Promote arts and sciences<br />

In order to support the poor the<br />

Foundation founded the Teylers Almshouse, a<br />

place where women over a certain age could<br />

live.<br />

In order to stimulate liberal theology they<br />

founded the First or Divine Society (Het Eerste<br />

of Godgeleerd Genootschap).<br />

The Second or Physical Society (Het<br />

Tweede of Natuurkundig Genootschap) was<br />

founded to promote the arts and science. This<br />

last society accomplished the building of a<br />

Museum for Arts and Science, in order to fulfil<br />

the objectives of Teyler’s Will.<br />

Nowadays, the objectives seem an<br />

extraordinary mix of charity, religion, science<br />

and art. But Pieter Teyler was a Mennonite and<br />

one of his ancestors, a tailor, left Scotland<br />

because of his religion. Teyler was a prominent<br />

member of the Mennonite Church and also<br />

donated a lot of money to that church. The<br />

Mennonite Church in Holland was very liberal.<br />

They were open for all ideas of the Age of<br />

Enlightenment and Teyler was very interested<br />

in all the new ideas in art and science. He<br />

would have been a member of the Dutch<br />

Society of Science (De Hollandsche<br />

Maatschappij der Wetenschappen) in Haarlem<br />

if he was allowed. But in order to be a member<br />

of that society one had to be a member of the<br />

established Dutch Reformed Church. As a<br />

consequence, he and his friends gathered<br />

occasionally to see and discuss art and<br />

science in his Gentlemen's Room, behind his<br />

house.<br />

The Oval Room designed by Leendert<br />

Viervant, painted by Wybrand Hendriks, the<br />

second ‘Chatelain’ of the museum (© Teylers<br />

Museum).<br />

observatory). Cupboards are made in the<br />

walls, which are used as showcases on the<br />

ground floor and as bookshelves on the first<br />

floor. To access these bookshelves, you can<br />

walk along the gallery (which is closed to the<br />

public nowadays). In the beginning the<br />

showcases were used to exhibit crystals and<br />

fossils and in the middle of the room was a<br />

table for physical experiments. Later the<br />

showcases were stuffed with physical<br />

instruments and the crystals and minerals<br />

moved to showcases mounted on the<br />

experiment table.<br />

M. van Marum (1750-1837), the first Director<br />

The Book and Art Hall or Oval Room<br />

To understand why the Physical Society<br />

founded a museum for both arts and science,<br />

you should know that painters and sculptors at<br />

the end of the 18 th century also studied the<br />

physical reality. Nowadays a drawing often is<br />

called a study, but in those days science was<br />

an art; a free art. So the big oval room, the<br />

oldest part of Teylers Museum was called the<br />

Book and Art Gallery (De Boek- en Konstzael).<br />

It was a high hall, built in an early Dutch neoclassical<br />

style, with light only from above<br />

through windows immediately below the roof<br />

(which is adorned with an astronomical<br />

The scholar Dr. Martinus van Marum, the first<br />

director of Teylers Museum 1784-1837<br />

(© Teylers Museum).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 8

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

Martinus van Marum (1750-1837) was a<br />

student and family friend of Petrus Camper, the<br />

famous scholar of comparative anatomy in<br />

zoology and botany and professor at<br />

Groningen University. Van Marum made two<br />

dissertations, one on the movement of juices in<br />

plants and one on the movement of juices in<br />

the animal body compared with those in plants.<br />

The Second Fossil Room with Mosasaurus<br />

hoffmanni, the jaws of the mosasaur from the<br />

collection of Major Drouin purchased by Van<br />

Marum in 1784 (© Teylers Museum).<br />

He was promised the Chair in botany<br />

at Groningen University, but the Board of the<br />

University appointed a fellow-student of his<br />

instead. Van Marum felt unappreciated and left<br />

in anger for Haarlem, where there was a<br />

science loving upper class. In 1776 he settled<br />

as a physician and became a member of the<br />

Dutch Society. A year later he was appointed<br />

Director of the Natural History Cabinet of the<br />

Society, and the city of Haarlem appointed him<br />

as a public lecturer in mathematics and<br />

philosophy. In 1779 he was admitted to the<br />

Second Society of Teylers Foundation and<br />

immediately gained great influence in the<br />

discussions on the new Museum. Van Marum<br />

was appointed to be the first director and<br />

librarian of the Museum after the Oval Room<br />

was finished in 1804.<br />

Van Marum proposed to purchase<br />

anything excavated (such as minerals and<br />

fossils) for the showcases. In 1782 he had<br />

already bought some fossils in Maastricht for<br />

the Society, during his honeymoon trip! In 1784<br />

he bought the first jaws of the ‘Animal de<br />

Maestricht’, now named mosasaur, and the<br />

complete fossil collection of Major Drouin,<br />

consisting of fossils from St. Peter’s Mountain<br />

in Maastricht, Limburg, The Netherlands. In<br />

1784 he purchased a complete collection of<br />

crystals, minerals, rocks and fossils at an<br />

auction in Amsterdam.<br />

He gave lectures on geology and other<br />

earth sciences but understood that his<br />

knowledge in this field was limited. Therefore<br />

he travelled through Europe to meet scholars<br />

in the fields of geology, petrology, mineralogy,<br />

crystallography and palaeontology to discuss<br />

their fields of research. He also purchased<br />

fossils and casts, rocks and minerals, crystals<br />

and crystal-models from them.<br />

Also the study of physics was on his<br />

agenda and he started physical experiments in<br />

the Teylers Museum. Thus he established a<br />

sort of ‘empire of science’; he had a hortus<br />

botanicus, was director of the Natural History<br />

Museum of the Dutch Society and a geological<br />

and physical museum (Teylers). What was<br />

lacking was a zoological garden, but<br />

nevertheless, Teylers could measure itself<br />

against collections in cities such as Paris and<br />

London. Even Napoleon Bonaparte was so<br />

impressed that he made plans to dismantle the<br />

Oval Room to rebuild it in Paris. Fortunately,<br />

his plans never came to fruition…<br />

Though Van Marum spent nearly twice<br />

as much on the purchase of scientific<br />

instruments than on minerals and fossils, he is<br />

nevertheless responsible for nearly all<br />

minerals, rocks and crystals in the collection<br />

and laid the foundations of the palaeontological<br />

collection by obtaining the most important<br />

fossils, among which are the previous<br />

mentioned jaws of the mosasaur. Van Marum,<br />

Left. Pear-wood crystal-models according the<br />

Abbot Rene Just Hauÿ. Van Marum purchases<br />

about 600 of them in 1802. The collection is<br />

still almos t complete (© Teyler s Museum).<br />

Right. The mammoth skull purchased by Van<br />

Marum for the Dutch Society of Science in<br />

1824. In 1886 it came to the new museum<br />

(© Teylers Museum).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 9

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

who published this ‘Grand Animal de<br />

Maestricht’, regarded it as a whale, following<br />

the ideas of his professor, Petrus Camper. He<br />

concluded: "It could be a whale, but not a<br />

whale or dolphin we know. The shells from the<br />

St. Peter’s Mountain are very different from the<br />

shells in the collection of the Natural History<br />

Museum too." He did not conclude that this<br />

animal was extinct. Later his close friend<br />

Adriaan Gilles Camper, son of Petrus Camper,<br />

suggested that the animal was a giant monitor<br />

sea-lizard and contributed thus to the idea of<br />

his tutor, George Cuvier, that animals could<br />

become extinct.<br />

Another important fossil, purchased by<br />

Van Marum in 1802 on his longest journey,<br />

was the ‘Homo diluvii testis et theoscopus’<br />

(‘The Man who witnessed the Flood and who<br />

saw God’). He bought it from the grandchildren<br />

of Johann Jacob Scheuchzer in Zurich. But in<br />

1811 Cuvier proved, after preparing the<br />

forefeet, that the fossil was the remains of a<br />

giant salamander. The labour of Cuvier is still<br />

visible in the fossil!<br />

The last instance of an important fossil<br />

purchased by Van Marum is the skull of a<br />

mammoth. Initially, the directors of Teylers<br />

Foundation did not show much interest but Van<br />

Marum, more passionate for fossils than ever<br />

before, furiously bought the piece for the<br />

Natural History Museum. Years later, when this<br />

Museum was closed, the skull came to the<br />

new wing of Teylers Museum, but that was<br />

long after the death of Van Marum in 1837.<br />

J.G.S. van Breda (1788-1867), the second<br />

Director and collector.<br />

Gaining and losing<br />

In 1839 professor Jacob Gijsbertus<br />

Samuël van Breda succeeded Van Marum. He<br />

graduated as a physician and a philosopher,<br />

he started his career in 1816 as a professor at<br />

the Atheneum of Franeker in botany, chemistry<br />

and pharmacy. In 1821 he married the<br />

daughter of the Rector of the Atheneum,<br />

Adriaan Gilles Camper. The same year (this<br />

was after the unification of the northern and<br />

southern Netherlands), he was appointed<br />

professor at Ghent University (now in Belgium)<br />

in botany, zoology and comparative anatomy.<br />

He also became the Keeper of the natural<br />

history collections of this University and added<br />

a lot to its collections.<br />

In addition Van Breda was appointed as<br />

a member of the Commission for the<br />

Geological and Mineralogical Map of the<br />

Southern Netherlands in 1825. In fact he was<br />

the leading geologist who inspected the<br />

Homo dilluvii test is et theoscopus’ (‘The Man<br />

who witnessed the Flood and saw God’). A<br />

giant-salamander found in 1725 in the<br />

freshwater limestone quarry of Oeningen.<br />

Described by Johann Jacob Scheuchzer in his<br />

Physica Sacra (Holy Physics). George Cuvier<br />

unmasked ‘The Man of the Flood’ by preparing<br />

its forelegs (© Teylers Museum).<br />

Prof. Dr. J.G.S. van Breda, director of Teylers<br />

Museum 1839-1867 (© Teylers Museum).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 10

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

The holotype of Pterodactylus crassipes<br />

appeared to be the first ever found fossil of<br />

Archaeopteryx. Archaeopteryx lithographica,<br />

the fourth discovered specimen of the primeval<br />

bird has teeth and a reptile tail, but feathers<br />

like birds (© Teylers Museum).<br />

samples collected by two military officers who<br />

were responsible for the survey.<br />

His star at the University was rising. He<br />

was already appointed as Rector of Ghent<br />

University when he had to escape to the north<br />

because of the Belgian Revolt in 1830. Back in<br />

Holland he was appointed as a professor at<br />

Leiden University in geology and zoology.<br />

In 1838 Van Breda was appointed<br />

Secretary of the Dutch Society and, in 1839,<br />

Director of Teylers Museum. He knew from his<br />

experience in Belgium how important the role<br />

of fossils was for geology and that stimulated<br />

him to purchase many fossils for the collection.<br />

It was important that he had plenty of room for<br />

them; Van Marum had a small Fossil Room<br />

built in 1827, which is now the Numismatic<br />

Cabinet. In 1838, a new Paintings Room was<br />

built next to the Fossil Room so a big room<br />

was empty and suitable for a large collection;<br />

this became the Large Stone Room (De<br />

Groote Steenenkamer).<br />

Van Breda spent more than twice as<br />

much money purchasing fossils as Van Marum<br />

had done, but only half the amount of money<br />

for scientific instruments. He had the first<br />

choice in fossils of the freshwater limestone<br />

quarry in Oeningen. He obtained four more<br />

giant salamanders and hundreds of fossil<br />

fishes, insects, frogs, crabs, a snake, turtles<br />

and remains of mammals (among which the<br />

bones and tusks of an elephant) and leaves in<br />

concurrence with the Zurich professor Heer,<br />

who described them. This way professor Heer<br />

and Van Breda sponsored the quarry in<br />

Oeningen, which at that time was famous as<br />

the quarry of ‘The Man of the Flood’. When<br />

they stopped sending money the owner had to<br />

close it.<br />

More fossils were obtained from different<br />

quarries in the Altmühltal, Germany,<br />

predominantly fossil fishes and insects. But the<br />

most valuable collection was bought from the<br />

well-known fossil merchant Krantz in Bonn. It<br />

was the collection of flying and other reptiles<br />

described by Hermann von Meyer in ‘Fauna<br />

der Vorwelt’. Later, in 1970, professor John<br />

Ostrom from Yale University, USA, discovered<br />

that one of them was the first found fossil of<br />

Archaeopteryx lithographica. So, huge fossils<br />

from ichthyosaurians and crocodiles, all marine<br />

reptiles from Baden-Württemberg, Germany,<br />

covered the walls and Van Breda had bought,<br />

again via Krantz, a seacow and an archeocete,<br />

the first found complete skull of Zeuglodon<br />

macrospondylus being the holotype of<br />

Zeuglodon hydrarchus, from the badlands of<br />

Alabama. This specimen however, should<br />

have been determined as Zeuglodon<br />

brachyspondylus and its name is now Zygoriza<br />

kochii.<br />

Van Breda purchased many fossils for<br />

Zygorhiza kochii, holotype of Zeuglodon<br />

hydrarchus, an old whale from the Eocene of<br />

Alabama in the showcase. Below that, the<br />

model of Dorudon atrox, a more primitive<br />

whale from the Fayum, Egypt, which was<br />

exchanged by Dubois for a cast of the<br />

Zygorhiza kochii (© Teylers Museum).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 11

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

the Cabinet, but had no time to describe them<br />

because of his appointment as Chairman of<br />

the Commission for the Dutch Geological Map.<br />

This commission needed a lot of fossils and<br />

minerals to compare with the samples found in<br />

the field. Of course the books in the library and<br />

the collection of fossils in Teylers Museum<br />

played an important role in dating the<br />

geological layers, but the commission also<br />

collected fossils for their own museum in<br />

Haarlem. In order to describe Dutch fossils, the<br />

complete collection of reptile bones, which<br />

Petrus Camper bought in 1782 from the widow<br />

of J.L. Hoffman, was brought from Groningen<br />

University to Haarlem.<br />

Van Breda was not, as in Belgium,<br />

considered the most important geologist.<br />

Instead, his former student Dr. W.C.H. Staring,<br />

was appointed Secretary at the Commission.<br />

Staring drew all the work to himself. Van<br />

Breda, who had also quite a lot of reptile<br />

bones in his own collection as well as in<br />

Teylers Museum, tried to work with this<br />

material, but this work was already promised to<br />

professor H. Schlegel in Leiden. As a<br />

consequence, feelings of concurrence and<br />

envy disturbed the activities of the<br />

Commission, until it fell apart. Staring finished<br />

the job on his own.<br />

The condition of the Museum of Natural<br />

History of the Dutch Society was dreadful;<br />

leaking water from the roof was destroying the<br />

collection. The collection itself was badly<br />

documented and incomplete. So, in 1866 the<br />

oldest Natural History Museum (1759) in the<br />

Netherlands was closed and the collection was<br />

divided over different institutions; the fossils<br />

and minerals went to Teylers Museum.<br />

But the situation in Teylers Museum was<br />

also bad; Van Breda started to catalogue but<br />

did not complete it because of his numerous<br />

acquisitions. A lot of this material was not<br />

described and as Secretary of the Dutch<br />

Society he offered a prize for the description of<br />

the fossil fishes of Oeningen. The man who did<br />

this job was his successor at the Teylers<br />

Museum, Tiberius Cornelis Winkler.<br />

After his death in 1867 Van Breda's own<br />

collection was first offered to Teylers Museum<br />

but not accepted because of the price of 2000<br />

Dutch guilders (Van Breda's year salary was<br />

1400 Dutch guilders!). Consequently, the<br />

collection became divided and A.S. Woodward<br />

of the Museum of Natural History in London<br />

bought the best fossils for 450 Dutch guilders.<br />

Woodward also arranged the purchase of<br />

fossils by Cambridge University from the Van<br />

Breda collection. The rest was donated to<br />

Teylers Museum, leading to the third<br />

supplement on the catalogue of Winkler.<br />

Tiberius Cornelis Winkler (1822-1897),<br />

Registrar and first Curator.<br />

Catalogues and supplements<br />

Dr. Tiberius Cornelis Winkler started<br />

work immediately after his primary schooling<br />

with a job as a warehouse clerk. In the evening<br />

he studied French, German and English in<br />

such a way that he read, spoke and wrote<br />

fluently. His life changed when he got married.<br />

His brother-in-law studied medicine at<br />

Groningen University. This man encouraged<br />

him to study Latin and physics at the Clinical<br />

School in Haarlem.<br />

He settled as a physician in a small<br />

fishing village. There he became interested in<br />

fish, because one of his patients was stung by<br />

a weever, a stingfish. It appeared to be a<br />

serious case. Winkler became curious about<br />

Dr. T.C. Winkler, the first Curator 1867-1897<br />

made 6 catalogues and 5 supplements for the<br />

collection. Translated in 1861 Darwin’s ‘Origin<br />

of Species’, wrote many popular scientific<br />

books and articles about fossil and living<br />

creatures (© Teylers Museum).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 12

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

this fish and in 1856 he went to the library of<br />

the Teylers Museum for literature. There he<br />

met Van Breda, who helped him. He asked<br />

Winkler to write an article on the weever for the<br />

popular magazine on natural history Van Breda<br />

and others had founded in 1852, the ‘Album of<br />

Nature’ (‘Album der Natuur’). So a fruitful<br />

collaboration began between the old scholar<br />

and the autodidact. He became a regular<br />

author in the Album (more than 50 articles). I<br />

imagine that the conversation with Van Breda<br />

lead to the idea to translate Darwin's ‘Origin of<br />

Species’ into Dutch. So already in the 1860s<br />

the Dutch people could read the revolutionary<br />

ideas of Darwin in their own language. Van<br />

Breda asked Winkler to describe the fossil<br />

fishes of Oeningen for the prize of the Dutch<br />

Society. He did, and in 1861 it was finished<br />

and published. Then Van Breda asked him to<br />

do the same for the fishes of Solnhofen. He<br />

did, and in 1862 it was finished and published.<br />

The Board of Directors of the Teylers Museum<br />

was offered a nomenclature, a list of all the<br />

fishes with their Latin names classified in a<br />

French system according to Pictet's Traité de<br />

Paléontologie .<br />

The directors of the Teylers Foundation<br />

were very pleased with the careful and<br />

systematic work of Winkler and asked him to<br />

make a catalogue of the complete collection.<br />

Winkler started the catalogue and in 1863 the<br />

first volume, on the Palaeozoic fossils, was<br />

ready. His concept was very well considered.<br />

He first went to professor Harting, a member of<br />

the Commission of the Dutch Geological Map,<br />

for advice. Harting told him to number all the<br />

objects immediately when he found them. He<br />

also told him to divide the catalogue in three<br />

parts Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Cainozoic,<br />

and to start with the simplest creatures.<br />

Furthermore, Harting told him to use a<br />

handbook for this classification and he<br />

recommended Pictet. The first volume was a<br />

success and Winkler sent it to well known<br />

palaeontologists. Professor Bronn reviewed it<br />

in Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, saying "...<br />

indeed one can introduce this Catalogue as an<br />

example for all similar labour ..." (translated).<br />

Groningen University honoured him by offering<br />

him a honorary degree, also because of his<br />

translation of important books in 1864 and the<br />

Teylers Foundation honoured him with an<br />

appointment as the first Curator of the<br />

This holotype of Pterodactylus micronyx was<br />

part of the collection of Hermann von Meyer<br />

and was described by Winkler (1870)<br />

(© Teylers Museum).<br />

Palaeontological-Mineralogical Cabinet in<br />

1867.<br />

The catalogue came out in six volumes;<br />

the last one in 1868. As the work was just<br />

finished, Winkler discovered the first collection,<br />

purchased from Major Drouin, in a cupboard<br />

outside the Fossil Rooms! So he had to make<br />

the first supplement to the catalogue in 1868,<br />

immediately after the catalogues proper were<br />

finished. Even more fossils came in and other<br />

should go; the collection of fossil reptiles of<br />

Petrus Camper - Hoffmann's collection had to<br />

go back to Groningen. Fortunately, ‘ My friend<br />

Staring’, as Winkler used to put it, made that<br />

the fossils could stay in Teylers Museum, first<br />

on loan, then permanently. Winkler became<br />

interested in turtles, not only because of the big<br />

turtle Chelonia hoffmanni now Allopleuron<br />

hoffmanni, but also because of the various<br />

fossil turtles in the collection; his book on<br />

turtles was finished in 1869.<br />

New books and new insights made a<br />

revision necessary and the last supplement,<br />

the fifth, appeared in 1896, a year before he<br />

died. True, this might be regarded as a dull and<br />

boring, but necessary job, and Winkler had<br />

other things to do too. He learned ten more<br />

languages, among which was Volapuk (the<br />

precursor of Esperanto), but also articles and<br />

books had to be written. He loved to write<br />

informative books for interested people and to<br />

illustrate them with humorous and romantic<br />

stories. He got his chance when the New<br />

Museum was built. Only one fossil was<br />

purchased for the New Museum, an almost<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 13

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

complete skeleton of Plesiosaurus<br />

dolichodeirus from the Lias limestone of Lyme<br />

Regis, Great Britain. This largest object in the<br />

collection was the first fossil placed in the new<br />

First Fossil Room. All the fossils had to be<br />

replaced in showcases and drawers and<br />

Winkler complained that he became short of<br />

space to store it. Winkler did suffice to write the<br />

new position of the fossils in his old catalogues<br />

and supplements and he wrote a ‘Guide for the<br />

Visitor’ in Dutch and French. All his talent in<br />

storytelling could be used and all his narratives<br />

told. “In 1863 Professor Van Beneden from<br />

Belgium came to see the Zeuglodon<br />

macrospondylus (Archaeocete VV) and<br />

pointing at the nostrils he cried: "... c' est un<br />

phoque monsieur, je vous assure c'est un<br />

phoque!"” (it’s a seal sir, I assure you it’s a<br />

seal). Cleverly Winkler declared it was a<br />

seacow.<br />

Winkler also retold the story of<br />

Solomon's judgment. In a cellar in Paris a huge<br />

bone of a whale was discovered. Van Marum<br />

and Cuvier both wanted it and to avoid an<br />

escalation in the price they decided to divide it.<br />

So they asked for a carpenter with a saw.<br />

When the carpenter was already sawing,<br />

Cuvier could not bare it and left the fossil to<br />

Van Marum. But…although Cuvier was a real<br />

palaeontologist he was only a child in 1796!<br />

When in 1896 the medical officer<br />

Eugène Dubois brought Winkler a cast of<br />

Pithecanthropus erectus (the Java man and<br />

then considered the missing link between man<br />

and ape and the utter proof that Darwin was<br />

right about the descent of man) Winkler felt<br />

honoured and the story he wrote about this<br />

fossil was one of his last.<br />

and to find fossils. His father was willing to tell<br />

all the stories about his findings. Then the time<br />

came for him to go to high school. Normally a<br />

Roman Catholic father would have chosen a<br />

Roman Catholic Latin School, but he chose a,<br />

in that time very modern type of school, the<br />

HBS (Higher Citizens School) in Roermond.<br />

There, young Eugène got involved in<br />

discussions on evolution versus creation and<br />

‘The Descent of Man’. The false arguments of<br />

his teacher in German language convinced him<br />

of the opposite. Later he recounted the<br />

comments of his teacher ‘Affen bauen keine<br />

Kathedrale!’ (‘Apes do not build cathedrals’).<br />

After high school Dubois went to<br />

Amsterdam University to study medicine. He<br />

was very interested in anatomy and when he<br />

finished his studies he became assistant to the<br />

professor in anatomy and teacher at the<br />

Academy of Art in Amsterdam. One year later<br />

he was appointed lector in anatomy and was a<br />

candidate to succeed his professor.<br />

Suddenly, Dubois ended his career and<br />

went to the Dutch Indies as a medical officer.<br />

No one could understand this decision,<br />

because ‘only unsuccessful doctors went to the<br />

Indies’, as was the common thought. Dubois<br />

learned from the books of Heackel that ‘the<br />

missing link’, the link between<br />

Eugène Dubois (1858-1940)<br />

The ‘missing link’<br />

Marie Eugène François Thomas Dubois<br />

was born in 1858, a year before ‘The Origin of<br />

Species’ and he grew up in a Roman Catholic<br />

family. His father was the chemist of Eysden, a<br />

village on the banks of the river Maas. When<br />

young Eugène looked out of his bedroom<br />

window he could see the St. Peter’s Mountain<br />

on the opposite bank of the river. The young<br />

boy loved to stray with his father through the<br />

Limburg landscape to collect medicinal herbs<br />

Prof. Dr. Eug. Dubois (1858-1940) (© Teylers<br />

Museum).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 14

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

Dubois, on the right with fringe, without<br />

moustache, went to the Dutch Indies as a<br />

medical officer to do scientific research<br />

(© Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum,<br />

Naturalis).<br />

ape and man, could be found on a place where<br />

currently ape and man are living. He asked the<br />

government for money to organize an<br />

expedition to Africa, to the place where gorillas<br />

and chimpanzees were to be found. The<br />

government refused. Then he realized that in<br />

the Dutch Indies man and ape (the orangutan),<br />

are found too and going there without<br />

high costs was only possible by joining the<br />

colonial army. Perhaps he knew that the army<br />

also did some scientific work on expeditions<br />

‘terra incognita’.<br />

In the Indies, Dubois was first<br />

commissioned at a hospital on Sumatra. There<br />

was no time for fossil hunting, but he wrote an<br />

article, ‘About the desirability of an<br />

investigation of the diluvial faunas of the Dutch<br />

Indies, especially Sumatra’ (translated). He<br />

asked for a transfer to a small hospital, where<br />

he had time to examine caves. He found<br />

fossils, not only bones from elephants, tapirs,<br />

pigs and cows, but also from gibbons and<br />

orang-utans. With these fossils and with<br />

support from the world of science Dubois could<br />

convince his superiors. In 1888 he got a<br />

commission to do palaeontological<br />

investigations on Sumatra and Java. He also<br />

got two sergeants to his command and the<br />

labour of fifty convicts. He found some other<br />

caves on Sumatra with the same fossils and<br />

then he explored Java. One of the reasons of<br />

doing this was the discovery of a skull of the<br />

Wadjak-man on Java. Dubois identified this as<br />

from another human race than was then living<br />

on Java, but also saw that this was not the type<br />

of skull he was looking for. Work began on<br />

Java with caves too, but quickly they started<br />

excavation in the Kendeng hills. In the dry<br />

season, when the ground was covered with<br />

leaves, they went to the river Solo, near Trinil.<br />

The high walls of the bank of this river were full<br />

of fossils, but in the wet season the water was<br />

too high to work there. So the two sergeants<br />

and their convicts swapped over from one<br />

locality to the other and Dubois came to look at<br />

the fossils from time to time.<br />

One day, just at the end of the dry<br />

season, one of the sergeants told him they had<br />

found the carapace of a tortoise. When Dubois<br />

saw it he was thrilled, this was what he was<br />

looking for – not a tortoise, but the cap of a<br />

very primitive skull. But when he studied the<br />

skull during the wet season, he hesitated, it<br />

was too ape-like. So he started an article on<br />

this fossil, which he named Anthropopithecus<br />

(= ape-man). When the dry season returned,<br />

the convicts continued their job and twelve<br />

meters from the place where the upper part of<br />

the skull was found, they discovered a human<br />

femur. The anatomist Dubois at once saw that<br />

this creature walked upright and never<br />

hesitated that this bone belonged to the same<br />

individual as the skull cap. So in his description<br />

of 1894 he changed the name in<br />

Pithecanthropus erectus (= man-ape), a name<br />

already given by Heackel to his hypothetical<br />

ancestor of mankind; Dubois found the<br />

‘missing link’.<br />

In 1894 he went back to The<br />

Netherlands, where the debate over his finds<br />

The skull cap and femur of Pithecanthropus<br />

erectus Dubois, 1894, now Homo erectus, the<br />

Java-man excavated near Trinil from the bank<br />

of the Solo-river at Java (RI) (© Nationaal<br />

Natuurhistorisch Museum, Naturalis).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 15

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

was going on as it was in the rest of Europe.<br />

The common opinion was that the skull and the<br />

femur were not from the same individual and<br />

also not from the same species. They could not<br />

imagine that in most circumstances fossil<br />

bones of one individual do not stay together<br />

but become dispersed by other animals or by<br />

flowing water; most of the comparative<br />

anatomists studied complete skeletons and not<br />

isolated bones.<br />

Dubois was appointed Director over his<br />

collection in the State Museum of Natural<br />

History in Leiden and lived in The Hague. In<br />

Leiden he had all kinds of fossils and<br />

skeletons, which he could compare with the<br />

more than 20.000 fossils he found in the<br />

Indies. Amsterdam University honoured him by<br />

offering a honorary degree in 1897 and Dubois<br />

moved with his family to Haarlem in the same<br />

year.<br />

In 1899 he became a professor in<br />

geology and crystallography at Amsterdam<br />

University and the successor of Winkler, the<br />

Curator of the Palaeontological-Mineralogical<br />

Cabinet at the Teylers Museum.<br />

The first activity at the Teylers Museum<br />

was to prepare fossils of mosasaurs (maybe to<br />

gain experience to empty the part of the skull<br />

of the Pithecanthropus, because he was<br />

interested in the inside of the skull, the<br />

endocranium). He compared endocranial casts<br />

from different fossils. In the Teylers Museum is<br />

a collection of casts of fossil hominids, mostly<br />

Neanderthals, but also from Australopithecus.<br />

There are endocranial casts of all the skulls as<br />

well.<br />

clay-pits in Tegelen. One of the directors,<br />

August Canoy, the nephew of Dubois’ wife,<br />

was willing to help him to get a collection from<br />

the clay-pits. Dubois paid the workmen to save<br />

the bones (they normally threw the bones back<br />

in the pits). Canoy arranged also that an older<br />

collection of bones would be transferred to the<br />

Teylers Museum. In this way, Dubois was able<br />

to establish a large fossil collection including<br />

two species of deer, two rhinos, a large horse,<br />

two beavers, a hippopotamus (which later<br />

proved to be a pig), a white-tailed eagle, a<br />

tortoise and a pike. Unfortunately, what he had<br />

hoped for did not turn up: a fossil of the first<br />

man of Limburg.<br />

Dubois, being a geologist, was curious<br />

about the thickness of the layer of clay and the<br />

layers underneath. Paid for by the Teylers<br />

Foundation, he set a borehole in the Canoy<br />

quarry and found a base with gravel on which<br />

he situated the Tiglian in the Pliocene era. In<br />

doing so, Dubois postulated a tertiary Ice-age.<br />

This resulted in a huge discussion with people<br />

of the Dutch Geological Survey who defined all<br />

the Ice-ages to the Pleistocene era and until<br />

today the Tiglian in The Netherlands is situated<br />

in the Pleistocene era, while in other countries<br />

it is of Pliocene age!<br />

Dubois and his assistants<br />

Dubois bought only one really<br />

important large fossil for the collection. In 1914<br />

Dubois and the fossils from the clay-pits of<br />

Tegelen<br />

The most important work Dubois did at<br />

the Teylers Museum was collecting fossils from<br />

Tegelen, a location near the German border<br />

and which had a ceramic industry continuing<br />

from Roman times onwards. In the quarries,<br />

the bones of Trogontherium, a beaver, were<br />

abundant. The Germans spoke about<br />

‘Trogontheriumtone’. Dubois heard already<br />

about these fossils in 1897, but in 1903 he<br />

travelled with two students to the St. Peter’s<br />

Mountain (where he purchased fossil driftwood<br />

with borings of mollusks). On his journey he<br />

visited the firm Canoy-Herfkens, working at the<br />

Antlers of the great deer of Tegelen,<br />

Eucladoceros tegulensis (Dubois, 1904), junior<br />

synonym of Eucladoceros ctenoides. Dubois,<br />

using nails, bamboo-pins and gypsum,<br />

restored the right antler. Professor Schaub in<br />

Basel modelled the left one in 1947 (© Teylers<br />

Museum).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 16

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

he obtained an Ichthyosaurus communis “mit<br />

Hauterhaltung” (‘with preserved skin’), from<br />

one of the Posidonian-slate quarries in<br />

Holzmaden, Germany. Dr. H.C. Bernhard Hauff<br />

himself prepared this fossil. The rest he<br />

purchased were casts or fossils, mostly for his<br />

own studies.<br />

Dubois had three jobs and for each one<br />

he had an assistant. In Amsterdam, Antje<br />

Schreuder did most of Dubois’ work as a<br />

professor. She also managed the collection of<br />

Tegelen, which Dubois collected with his<br />

students, and she became a specialist in the<br />

small mammals of Tegelen (humorously she<br />

called this ‘waistcoat pocket’ palaeontology). In<br />

Leiden he had an assistant too, Father J.A.A.<br />

Bernsen, who was a Roman Catholic priest.<br />

Bernsen catalogued the fossil collection from<br />

the Dutch Indies. Both received their doctor's<br />

degree on the Tegelen fossils. Father Bernsen<br />

specialised on the rhinos and Antje Schreuder<br />

on the beavers. The Teylers Foundation paid<br />

Bernsen’s publication (1927) and Schreuder<br />

published in the ‘Archives Teylers ‘ (1928). In<br />

about 1920 Dubois got an assistant at the<br />

Teylers Museum, Mrs. Lobry-de Bruijn. She<br />

had a special job: to make explanatory texts to<br />

accompany the fossil displays. The large texts<br />

in the showcases are from that time. The rough<br />

copies are still in the collection. No sentence<br />

stayed the same, Dubois corrected every word.<br />

When you see that, it is hard to understand<br />

why he did not do the work himself; this way<br />

the job would have taken one year (which he<br />

asked for) instead of the three years it actually<br />

took!<br />

So his assistants did the bulk of Dubois’s<br />

work. Dubois loved to be in Haarlem, walking<br />

in the dunes and to be with his collection at the<br />

Teylers Museum. He also enjoyed meeting<br />

other scholars like professor H.A. Lorentz , the<br />

Nobel Prize winner who had his own<br />

laboratory at the Teylers Museum.<br />

In 1906 Dubois bought badlands near<br />

Haelen in Limburg, not far from Tegelen. In the<br />

beginning he had a simple shed in which he<br />

lived, unconventionally and mostly alone. The<br />

people in the region called him ‘the beggar’<br />

and so he named his mansion, which he built<br />

later, ‘De Bedelaer’ (‘The Beggar’). He asked<br />

his students to come there to do their<br />

preliminaries and sometimes, when the<br />

weather was bright and the water warm, they<br />

swam together in the fen during the exams. In<br />

the meantime, Dubois tried to improve the poor<br />

water quality with guano from bats. Near the<br />

fen was a huge tower for bats, behind his<br />

mansion was a smaller one whilst the tower of<br />

the building was used for bats too. He was the<br />

first to discover the nutrification of freshwater<br />

by pollution.<br />

The wandering of Pithecanthropus erectus<br />

The discussion about the<br />

Pithecanthropus erectus was hushed after<br />

1900, when Dubois showed the hominid at the<br />

World Fair in Paris. Dubois was done with all<br />

the critics and misunderstandings. He became<br />

paranoid and dug a hole under his table in the<br />

kitchen to hide his hominid fossils and had no<br />

place to show them! He slept with a pistol<br />

under his pillow, afraid of ‘creationist burglars’.<br />

When scientists asked to study the skull and<br />

the other hominid fossils, he answered that he<br />

had no place to show it. They complained to<br />

the Directors of the Teylers Foundation and in<br />

1923 the Directors procured a safe for the<br />

fossils in the Teylers Museum. When they<br />

heard about this in Leiden, they claimed the<br />

fossils, because they were excavated in<br />

military service and thus State property. One of<br />

his assistants, professor Brongersma, retold<br />

the event of bringing the fossils to Leiden.<br />

Here, one assistant walked in front and another<br />

assistant bearing a box with the skull followed.<br />

Behind them came Dubois with his pistol in the<br />

pocket of his coat. This strange group walked<br />

through Haarlem and got on the train to the<br />

State Museum of Natural History in<br />

The tomb of Dubois at the graveyard in Venlo<br />

near Tegelen, The Netherlands (© J.C. van<br />

Veen).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 17

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

Leiden. The fossils are still in the same safe,<br />

because the directors of the Teylers<br />

Foundation, as good losers, granted the safe to<br />

the Leiden Museum as well.<br />

Dubois continued to be Curator until his<br />

death in 1940, but for years he did not go to the<br />

Teylers Museum. He died in Haelen and is<br />

buried in the graveyard in Venlo, in the<br />

Protestant part in non-consecrated soil; he was<br />

not welcome in the Roman Catholic section.<br />

When I saw his tomb I was astonished, he lies<br />

beneath a big rectangular stone with his name,<br />

Prof. Dr. Eug. Dubois. He lost his Christian<br />

names and above this was the ‘Pirate Ensign’ –<br />

the ‘Jolly Roger’ - two crossed bones with the<br />

part of the skull of Pithecanthropus erectus, the<br />

Java-man, the ‘missing link’.<br />

World War II, an interregnum<br />

During World War II Cornelis Beets was<br />

the curator of the Palaeontological-<br />

Mineralogical Cabinet. The museum was<br />

closed. The showcases were covered with<br />

sandbags protecting the objects against shells<br />

from bombing, which fortunately never came.<br />

The only feat of arms of this geologist was to<br />

look for people who could describe the bones<br />

from Tegelen he found in boxes and baskets in<br />

all kind of places. Antje Schreuder was one of<br />

them and also Dick A. Hooijer. Later, when he<br />

was 60 years old, he became the Director at<br />

the State Museum for Geology and Mineralogy<br />

in Leiden.<br />

Entomology Department and after several<br />

years he became Curator of the Mollusk<br />

Department. In 1946 he was appointed Curator<br />

of the Palaeontological-Mineralogical Cabinet<br />

of the Teylers Museum.<br />

The first group of animals he examined<br />

in the Cabinet were the Teutoidea (fossil squid)<br />

from the lithographic limestone of Solnhofen,<br />

Germany. In doing so, he made the sixth<br />

supplement of the systematic catalogue<br />

(1949), which Winkler had begun. But Van<br />

Regteren Altena wrote it in English, the new<br />

international scientific language instead of<br />

French: Systematic Catalogue of the<br />

Palaeontological Collection, 6th supplement.<br />

Teutoidea. In the meantime Dick Hooijer<br />

determined the bones from Tegelen. The list<br />

grew and grew and with other data Altena<br />

gathered, they could publish a seventh<br />

supplement: Vertebrata from the Pleistocene<br />

Tegelen Clay, Netherlands.<br />

At this time Altena was not content with<br />

the dependency on the printed catalogues and<br />

he started a card-index. In Amsterdam an<br />

international symposium on insects was<br />

organized. A good opportunity to reorganize<br />

the showcases with insects from Oeningen and<br />

Solnhofen. A lot of them were originals (O=<br />

published specimen), types (T=first described<br />

specimen, now holotypes), paratypes (P=<br />

together described specimen) or syntypes<br />

(S=used by description, but not the holotype).<br />

C.O. van Regteren Altena (1907-1976);<br />

a facelift of the Collection.<br />

Mollusks, insects and ... Tiglian bones as<br />

heritage<br />

Carel Octavianus van Regteren Altena<br />

studied biology at Amsterdam University, with<br />

some palaeontological and geological subjects<br />

as well. When he was about fifteen he made<br />

his first publication (on squid). He had a<br />

special interest in marine mollusks and after he<br />

finished his studies he got a grant to produce a<br />

publication on the seashells of the Dutch coast<br />

and estuaries. That book was such a success<br />

that in 1937 Amsterdam University decided<br />

that this was his thesis. In 1941 he was<br />

appointed Assistant Curator at the State<br />

Museum of Natural History in Leiden in the<br />

Dr. C.O. van Regteren Altena, the third Curator<br />

from 1946-1976 (© Teylers Museum).<br />

© <strong>PalArch</strong> Foundation 18

www.<strong>PalArch</strong>.nl Newsletter 1, 1 (2004)<br />

After World War II scientists were very<br />

concerned about the fate of types. A lot of the<br />

types in Germany were destroyed during the<br />

war or lost, so they agreed to mark them with<br />

the characters O, T, P or S so they could be<br />

found easily in case of emergency. He made a<br />

type-script too with all the types in it he knew<br />

(mostly insects and bones from the Tiglian<br />

clay). The cards in the index got a coloured clip<br />

if the fossil was some kind of type or an<br />

original. Altena also started a library with the<br />

offprints he got in exchange for his scientific<br />

articles, and of course a card-index organised<br />

by author and year with it.<br />

Changes in the showcases<br />

Although Van Regteren Altena did not<br />

purchase any fossils for the collection, he<br />

made a lot of changes in the showcases. In<br />

1970 a gifted retired housepainter became his<br />

assistant, Mr. J. Klinker. All the showcases<br />

were painted and the flat showcases got a<br />

base of drawing paper. He also decided that<br />

the showcases were too full. Sometimes more<br />

than half of the number of fossils where placed<br />

in the drawers below the cases; half of the<br />

minerals and crystals in the Oval Room were<br />

stored in cardboard boxes. The texts with the<br />

fossils were altered. Not an occasional printed<br />

or hand-written name near some fossils, like in<br />

the Winkler exhibition, but each fossil got its<br />

own plate, written by Mr. Klinker, with scientific<br />

name, a short explanation in Dutch, the<br />

catalogue number, the stratigraphical period<br />

and find locality. He also made revisions of the<br />

scientific names by using recent names and he<br />

gave the collection a more scientific<br />

appearance by adding plates in some<br />

showcases with a zoological classification.<br />

Large plates denoted class, and small plates<br />

gave details of order and family.<br />

Between 1970 and 1980 Klinker<br />

restored all the big fossils from Lyme Regis<br />

and Holzmaden. The stone surrounding the<br />

plesiosaur was fractioned because the bones<br />

were blooming grey with pyrite disease. The<br />

bones were impregnated by a paraffin solution<br />

in petrol, the stone repaired with a mix of<br />

Araldite (an epoxy resin) and clay. So the idea<br />

that everything in the Teylers Museum stayed<br />

unchanged is an illusion. Van Regteren Altena<br />

died in 1976 and after his death Klinker worked<br />

for three years on his own on the collection and<br />

died in 1982.<br />

Walenkamp, De Vos and Lydie Touret<br />

In 1979 Dr. J.H.C. Walenkamp was<br />

appointed Curator of the Palaeontological-<br />

Mineralogical Cabinet. His thesis was on seaurchins.<br />

He was assisted by a student, Rob<br />