Part I. R& D Status - pcaarrd - Department of Science and Technology

Part I. R& D Status - pcaarrd - Department of Science and Technology

Part I. R& D Status - pcaarrd - Department of Science and Technology

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

R&D <strong>Status</strong><br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

4 ............................................................................................................. R&D <strong>Status</strong> <strong>and</strong> Directions

Papaya Industry Situation<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

World Supply <strong>and</strong> Dem<strong>and</strong><br />

From 1992 to 2003, the world’s papaya<br />

production averaged 5.49 million tons (M t)<br />

(Fig. 2). Brazil was the consistent top producer<br />

(25%), followed by Nigeria (13%), Mexico (13%),<br />

<strong>and</strong> India (12%). The Philippines, averaging 1%,<br />

ranked 14 th .<br />

According to the Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture<br />

Organization (FAO), there was an upward trend in<br />

both the export <strong>and</strong> import trading <strong>of</strong> fresh papaya<br />

in the global market.<br />

From 1996 to 2002, export trade <strong>and</strong> world<br />

imports posted an annual growth rate <strong>of</strong> 13%<br />

<strong>and</strong> 10%, respectively. Moreover, the world’s<br />

annual export trade was 159,056 t valued at<br />

US$ 102.56 M. Mexico (38%) <strong>and</strong> Malaysia<br />

(27%) cornered the export trade. The Philippines,<br />

10 th among world’s fresh fruit exporter, supplied<br />

1.3% only. For annual imports, the United States<br />

accounted for 45% followed by Singapore (16%)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Hong Kong (12%). World importation,<br />

however, increased from 115,473 t in 1996 to<br />

197,124 t in 2002.<br />

The Philippine Papaya Industry<br />

The Philippine Papaya Varieties<br />

Papaya, grown almost throughout the country,<br />

serves as a backyard <strong>and</strong> a plantation crop, <strong>and</strong> as<br />

a component <strong>of</strong> the multiple cropping systems,<br />

usually with coconut, c<strong>of</strong>fee, <strong>and</strong> pineapple.<br />

Congo<br />

4%<br />

Indonesia<br />

8%<br />

Others<br />

14%<br />

Philippines<br />

1%<br />

Brazil<br />

25%<br />

Venezuela<br />

2%<br />

India<br />

12%<br />

Thail<strong>and</strong><br />

2%<br />

Mexico<br />

13%<br />

China<br />

3%<br />

Nigeria<br />

13%<br />

Peru<br />

3%<br />

Total production = 5.49 M t<br />

Fig. 2. Average production (t) <strong>of</strong> world’s top papaya producers, 1992–2003 (FAO).<br />

Papaya.............................................................................................................................................................. 5

The Philippine papaya has several varieties.<br />

These are ‘Solo,’ ‘Cavite Special,’ ‘Legaspi<br />

Special,’ ‘Morado,’ <strong>and</strong> the ‘Sinta’ hybrid.<br />

The Solo papaya, a hermaphrodite, is so-called<br />

because one fruit (about 0.45 kg) is enough for<br />

one individual’s consumption. It has four different<br />

types, namely: ‘Kapoho,’ ‘Waimanalo,’ <strong>and</strong> the redfleshed<br />

‘Sunrise’ <strong>and</strong> ‘Sunset.’ It produces highquality<br />

fruits with excellent flavor, which is suited<br />

for the export market (PCARRD 1984).<br />

In fact, the Philippines’ export variety for fresh<br />

papaya is based mainly on Solo papaya, which is<br />

grown in large farms owned by multinational<br />

companies.<br />

Predominantly grown in Cavite <strong>and</strong> in the<br />

neighboring provinces, the Cavite Special papaya<br />

is relatively dwarf <strong>and</strong> a hermaphrodite (PCARRD<br />

1984). It flowers 6–8 months after planting. Its ripe<br />

fruits, with yellow-orange flesh (usually more than<br />

3 kg), can be harvested in about 10–12 months<br />

after planting.<br />

Like Cavite Special, Legaspi Special has large<br />

fruits with thick red flesh. It weighs more than<br />

3 kg. Also, it is predominantly grown in the Bicol<br />

region, especially in Albay.<br />

Papaya-growing companies put the red-fleshed<br />

Morado, like Cavite Special, in cans along with<br />

other tropical fruits.<br />

In 1995, the University <strong>of</strong> the Philippines Los<br />

Baños-Institute <strong>of</strong> Plant Breeding (UPLB-IPB)<br />

released the Sinta hybrid.<br />

This semi-dwarf hybrid moderately tolerates<br />

papaya ringspot virus (PRSV); matures in<br />

8–9 months; <strong>and</strong> produces medium-sized fruits<br />

(1.2–2.0 kg) with sweet, yellow, thick, <strong>and</strong> firm<br />

flesh. With a 2 m x 3 m planting distance <strong>and</strong> good<br />

management practices, Sinta papaya could yield<br />

40–60 t <strong>of</strong> fruits (17–0 fruits/tree) within 15 months<br />

from transplanting. Moreover, the recommended<br />

harvesting for Sinta papaya should be done in one<br />

fruiting cycle only, particularly in high disease<br />

pressure areas; <strong>and</strong>, at least three cycles in isolated<br />

areas or those with less disease pressure.<br />

Unfortunately, all the varieties are susceptible<br />

to papaya ringspot (PRS), which is caused by<br />

PRSV.<br />

PRS Outbreak in the Philippines<br />

Until the early ‘80s, growers in Southern<br />

Tagalog found a good business in papaya because<br />

<strong>of</strong> its year-round production <strong>and</strong> good income.<br />

Growers then could harvest up to<br />

39 fruits per tree. In three years, they could harvest<br />

as much as 62,400 fruits in a hectare with<br />

1,600 trees (PCARRD 1984).<br />

In 1984, the PRS disease outbreak wreaked<br />

havoc on the thriving papaya industries in Southern<br />

Tagalog <strong>and</strong> in the Bicol region. In fact, growing<br />

papaya with severe infection became unpr<strong>of</strong>itable<br />

(Sumalde 1995).<br />

PRS affects all stages <strong>of</strong> plant growth, i.e., from<br />

seedling to maturity stage. Green concentric<br />

ringspots appear on the fruit surface. Other<br />

symptoms include yellowing, mosaic, <strong>and</strong> deformed<br />

leaves; oily streaks on the stem <strong>and</strong> petioles; stunted<br />

growth; <strong>and</strong> sterile fruits.<br />

In 1992, PRS occurred only in Luzon. In 1996,<br />

it reached the Ilocos, Cordillera, Central Luzon,<br />

Southern Tagalog, Bicol, <strong>and</strong> Central Visayas<br />

(Negros Oriental) regions (Villegas 1996). The<br />

disease severely infected the areas near Silang,<br />

Cavite where the disease originated in 1982 (Bato<br />

<strong>and</strong> Ceballo 1992). In 2003, it reached Leyte <strong>and</strong><br />

Panay (Magdalita 2003) <strong>and</strong> was observed in<br />

South Cotabato <strong>and</strong> some parts <strong>of</strong> General Santos<br />

City, Davao del Sur, <strong>and</strong> Davao del Norte<br />

(Herradura 2003).<br />

Statistics has shown the damaging effect <strong>of</strong> the<br />

disease. For instance, Southern Tagalog’s<br />

production drastically declined to about 10,274 t in<br />

1987 from 36,310 t in 1981 (Bureau <strong>of</strong> Agricultural<br />

Statistics [BAS]). In 2001, its production reached<br />

25,475 t indicating a minor turnaround.<br />

Since the disease outbreak, efforts have been<br />

focused in coming up with management strategies.<br />

Included in these strategies is a quarantine regulation<br />

issued by the DA-Bureau <strong>of</strong> Plant Industry<br />

(DA-BPI). The regulation prohibits transporting<br />

fruits <strong>and</strong> planting materials from Luzon to avoid<br />

spreading the disease <strong>and</strong> protect the commercial<br />

papaya industries in Mindanao. Efforts have gained<br />

some headway as national production output<br />

generally increased in the ‘90s.<br />

6 ............................................................................................................. R&D <strong>Status</strong> <strong>and</strong> Directions

After the PRS Outbreak<br />

From a pre-PRS period <strong>of</strong> 95,550 t in 1982,<br />

production output went down to 88,388 t in 1987;<br />

but reached the 100,000 t level in 1994. For<br />

the next five years, national production was almost<br />

at a plateau before it markedly increased to as much<br />

as 120,000 t in 2000 (Fig. 3).<br />

The area devoted to papaya production also<br />

steadily increased from 1996 to 2000 <strong>and</strong> slightly<br />

leveled <strong>of</strong>f in 2000. Papaya, among the leading fruit<br />

crops grown in the country, ranked sixth in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

area planted <strong>and</strong> fifth in terms <strong>of</strong> volume produced<br />

in 2000 (Table 1).<br />

From 1997 to 2001, Southern Tagalog had the<br />

largest papaya hectarage (1,304–1,463 ha),<br />

followed by Southern Mindanao (815–879 ha) <strong>and</strong><br />

Western Visayas (712–779 ha). The area planted<br />

in most regions did not vary so much through the<br />

years, except in Central Mindanao where there was<br />

an abrupt increase from 460 ha in 1998 to 855 ha<br />

in 2001. The Autonomous Region in Muslim<br />

9,000<br />

8,000<br />

7,000<br />

6,000<br />

140,000<br />

120,000<br />

100,000<br />

Area (ha)<br />

5,000<br />

4,000<br />

80,000<br />

60,000<br />

Volume (t)<br />

3,000<br />

2,000<br />

1,000<br />

-<br />

Area (ha)<br />

Volume (t)<br />

1982 1984 1987 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001<br />

Year<br />

40,000<br />

20,000<br />

-<br />

Fig. 3. Area (ha) <strong>and</strong> volume (t) <strong>of</strong> papaya production in the Philippines, 1982–2001 (BAS).<br />

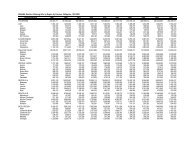

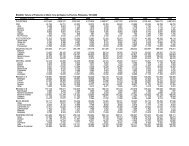

Table 1. Area (ha) <strong>and</strong> production (t) <strong>of</strong> ten important fruit crops in the Philippines, 2000 (BAS).<br />

Commodity Area (ha) Production (t)<br />

Banana 382,491 4,929,570<br />

Mango 133,815 848,328<br />

Pineapple 42,968 1,559,563<br />

Citrus (calamansi <strong>and</strong> pummelo) 24,066 227,169<br />

Jackfruit 11,999 51,163<br />

Papaya 8,440 121,304<br />

Durian 7,010 25,764<br />

Avocado 5,124 38,086<br />

Sugar apple 3,041 5,340<br />

Mangosteen 1,354 4,692<br />

Papaya.............................................................................................................................................................. 7

Mindanao (ARMM) (91–97 ha) had the least<br />

area planted to papaya.<br />

Supply <strong>and</strong> Dem<strong>and</strong><br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> volume <strong>of</strong> production, Southern<br />

Mindanao (24,321 t) produced the highest average<br />

volume (Fig. 4), followed by Southern Tagalog<br />

(20,671 t), <strong>and</strong> Northern Mindanao (17,088 t).<br />

From 1996 to 2000, the top producers were<br />

Laguna, Cavite, Camarines Sur, <strong>and</strong> Quezon<br />

in Luzon; Cebu in Visayas; <strong>and</strong> Misamis Oriental,<br />

North <strong>and</strong> South Cotabato, Davao City, <strong>and</strong> Davao<br />

del Norte in Mindanao (Table 2). From 1994 to<br />

2001, the growth rate for volume <strong>of</strong> papaya<br />

(3.57%) was almost similar to the papaya hectarage<br />

(3.51%) (Table 3).<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> papaya utilization, in an average<br />

volume <strong>of</strong> 109,730 t (1992–2001), about 92% was<br />

consumed locally as food; 2%, exported; <strong>and</strong><br />

6%, used as feed/wasted (Fig. 5).<br />

From 1992 to 2001, papaya supply in the<br />

Philippines increased (Table 4). In 2001, the<br />

country’s supply was more than enough to meet<br />

local dem<strong>and</strong>. Even so, there were regions where<br />

supply could not cope with the dem<strong>and</strong>. These were<br />

Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR), Central<br />

Luzon, ARMM, Caraga, Central Mindanao, <strong>and</strong><br />

all the Visayas regions. The National Capital Region<br />

had practically zero production. The per capita<br />

consumption ranged from 1.33 to 1.51 kg/year for<br />

an average <strong>of</strong> 1.42 kg/year for 10 years.<br />

Export<br />

The Philippines exported fresh (1,119 t) <strong>and</strong><br />

dried papaya (240 t) at an average <strong>of</strong> 1,359 t<br />

annually from 1996 to 2000 (Table 5). The value<br />

for dried papaya exports, however, declined from<br />

1996 to 1999 <strong>and</strong> slightly increased in 2000.<br />

Total exports, likewise, declined from 1996<br />

to 1998 but bounced back in 1999 <strong>and</strong> in 2000<br />

(Fig. 6). Fresh papaya exports accounted for 82%<br />

<strong>of</strong> total exports, while dried papaya accounted<br />

for 18%.<br />

The same erratic trend was observed in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> value <strong>of</strong> papaya exports, particularly for<br />

fresh papaya which ranged from US$85,280 to<br />

US$3.3 M (Fig. 7).<br />

From 1996 to 2000, Japan (66%) <strong>and</strong> Hong<br />

Kong (29%) imported 95% <strong>of</strong> the total volume <strong>of</strong><br />

Philippine fresh papaya.<br />

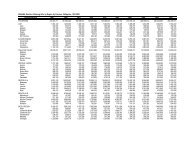

Table 2. Top ten papaya-producing provinces in the Philippines, 1996-2000. a<br />

Volume (t)<br />

Province 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Ave.<br />

Philippines 113,992 110,113 107,094 112,862 121,303 115,530<br />

1 Misamis Oriental 19,137 13,552 13,837 15,122 20,762 17,119<br />

2 South Cotabato 12,768 13,215 12,629 11,554 10,631 12,065<br />

3 Laguna 6,100 6,984 7,267 7,210 9,076 7,245<br />

4 North Cotabato 3,468 4,045 3,399 5,288 5,475 4,567<br />

5 Quezon 4,463 2,940 3,024 3,182 4,500 4,286<br />

6 Cavite 2,779 3,757 3,841 4,274 4,595 3,841<br />

7 Davao City 4,932 3,965 3,285 3,358 3,634 3,841<br />

8 Camarines Sur 3,221 2,915 4,327 4,221 3,683 3,690<br />

9 Cebu 4,005 3,260 2,820 3,105 4,094 3,554<br />

10 Davao del Norte 5,195 4,989 4,322 1,878 2,053 3,440<br />

Average 5,296<br />

a There are 79 papaya-producing provinces in the country.<br />

8 ............................................................................................................. R&D <strong>Status</strong> <strong>and</strong> Directions

30000<br />

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001<br />

25000<br />

Volume produced (t)<br />

20000<br />

15000<br />

10000<br />

5000<br />

0<br />

CAR<br />

Ilocos Region<br />

Cagayan Valley<br />

Central Luzon<br />

Southern Tagalog<br />

Bicol<br />

Western Visayas<br />

Central Visayas<br />

Eastern Visayas<br />

Western Mindanao<br />

Northern Mindanao<br />

Southern Mindanao<br />

Central Mindanao<br />

CARAGA<br />

ARMM<br />

Region<br />

Fig. 4. Volume (t) <strong>of</strong> papaya produced by region, 1997–2001, Philippines (BAS).<br />

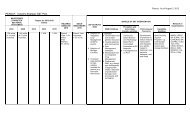

Table 3. Growth rate <strong>of</strong> area (ha) for <strong>and</strong> volume (t) <strong>of</strong> papaya production in the Philippines,<br />

1994–2001 (BAS).<br />

Area<br />

Volume<br />

Year ha Change (%) t Change (%)<br />

1994 7,052 104,250<br />

1995 7,161 1.55 108,409 3.99<br />

1996 7,375 2.99 113,974 5.13<br />

1997 7,490 1.56 110,112 -3.39<br />

1998 7,589 1.32 107,096 -2.74<br />

1999 7,913 4.27 112,862 5.38<br />

2000 8,440 6.66 121,304 7.48<br />

2001 8,416 -0.28 127,787 5.34<br />

Six-year growth rate from 1995 to 2001:<br />

1995 7,161 108,409<br />

2001 8,416 17.53 Total 127,787 17.87 Total<br />

3.51 Average 3.57 Average<br />

Papaya.............................................................................................................................................................. 9

Food<br />

(export)<br />

2%<br />

Feed/waste<br />

6%<br />

Food (local)<br />

92%<br />

Fig. 5. Utilization <strong>of</strong> papaya in the Philippines, 1992–2001 (BAS).<br />

Table 4. Supply <strong>and</strong> utilization accounts in papaya in the Philippines, 1992–2001.<br />

Utilization<br />

Supply<br />

(production, Exports Feed <strong>and</strong> Net Food Disposable<br />

Year t) (t) Waste (t) Total kg/yr g/day<br />

1992 93,968 1,268 5,562 87,138 1.36 3.72<br />

1993 97,537 2,084 5,727 89,726 1.37 3.76<br />

1994 104,250 3,426 6,049 94,775 1.38 3.78<br />

1995 108,409 2,313 6,366 99,730 1.46 4.00<br />

1996 113,974 1,400 6,754 105,820 1.51 4.14<br />

1997 110,112 407 6,582 103,123 1.44 3.95<br />

1998 107,096 3,307 6,227 97,562 1.33 3.65<br />

1999 112,862 1,203 6,700 104,959 1.40 3.85<br />

2000 121,304 2,524 7,127 111,653 1.46 4.00<br />

2001 127,787 4,163 7,417 116,207 1.49 4.09<br />

Average 109,729 2,209 6,451 101,069 1.42 3.89<br />

10 ............................................................................................................. R&D <strong>Status</strong> <strong>and</strong> Directions

Table 5. Volume (t) <strong>and</strong> value (‘000 US$ free on board [FOB]) <strong>of</strong> Philippine papaya exports (all<br />

products), 1996–2000.<br />

Volume (t)<br />

Ave.<br />

Growth %<br />

Product 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Average Rate (%) Share<br />

Fresh papaya 1,400 407 60 1,203 2,524 1,119 465 82<br />

Dried papaya 288 287 170 182 274 240 4 18<br />

3,000<br />

Dried papaya<br />

2,500<br />

Fresh papaya<br />

TOTAL<br />

Volume (t)<br />

2,000<br />

1,500<br />

1,000<br />

500<br />

-<br />

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000<br />

Year<br />

Fig. 6. Volume (t) <strong>of</strong> Philippine papaya exports (all products), 1996–2000 (National Statistics<br />

Office [NSO]).<br />

4,000<br />

3,500<br />

Dried papaya<br />

Value (‘000 US$ FOB)<br />

3,000<br />

2,500<br />

2,000<br />

1,500<br />

1,000<br />

Fresh papaya<br />

TOTAL<br />

500<br />

-<br />

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000<br />

Year<br />

Fig. 7. Value (‘000 US$ FOB) <strong>of</strong> Philippine papaya exports (all products), 1996–2000 (BAS).<br />

Papaya.............................................................................................................................................................. 11

New Zeal<strong>and</strong> was relatively a new export<br />

market, albeit small compared with Japan, but<br />

ranked 3 rd (1.9% share) among buyers <strong>of</strong> Philippine<br />

fresh papaya. Exporting fresh papaya to New<br />

Zeal<strong>and</strong> was made possible in 2000 after<br />

establishing the quarantine protocol agreement<br />

similar to what had been done with Japan <strong>and</strong><br />

South Korea.<br />

Making up the fourth <strong>and</strong> fifth top importers <strong>of</strong><br />

Philippine fresh papaya were Saudi Arabia (1.2%<br />

share) <strong>and</strong> United Arab Emirates (0.8% share).<br />

Singapore, China, South Korea, United States, <strong>and</strong><br />

the Canary Isl<strong>and</strong>s comprised the sixth up to the<br />

tenth top importing countries.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> value, Japan accounted for 90%<br />

share while Hong Kong had about 8% share. New<br />

Zeal<strong>and</strong>, however, accounted for 0.9% share.<br />

On the other h<strong>and</strong>, Australia imported most <strong>of</strong><br />

the Philippine dried papaya <strong>and</strong> obtained 73%<br />

share, followed by the United States with 20%<br />

share. Both countries also cornered 87% share <strong>of</strong><br />

the value <strong>of</strong> Philippine dried papaya exports. The<br />

other top importers <strong>of</strong> dried papaya were Canada,<br />

Germany, <strong>and</strong> Japan.<br />

Key Industry Players<br />

Generally, the Philippine papaya industry’s key<br />

players can be classified as papaya growers,<br />

contract growers, input suppliers, consumers, <strong>and</strong><br />

exporters.<br />

Papaya growers can be differentiated based on<br />

the size <strong>of</strong> their farms. Typical papaya growers,<br />

about 79% <strong>of</strong> all papaya growers, have less than<br />

3 ha. The other growers have 3–10 ha (18.4%)<br />

<strong>and</strong> more than 10 ha (2.5%) (NSO 1991). Large<br />

papaya growers such as T’Boli Agro-Industrial<br />

Development, Inc. (TADI), Del Monte Philippines,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Dole Philippines, Inc., operate in Mindanao.<br />

On the other h<strong>and</strong>, small-scale growers usually<br />

produce their own seeds or buy planting materials<br />

from local nurseries. The Philippine papaya<br />

production, except for the export variety Solo, is<br />

widely dispersed <strong>and</strong> mostly run on a backyard<br />

scale.<br />

Some companies enter into contract-growing<br />

arrangements with selected individual producers<br />

using their preferred cultivars. For instance, Del<br />

Monte Philippines has contract-growing<br />

arrangements with papaya farmers in Misamis<br />

Oriental <strong>and</strong> Bukidnon. They also produce their<br />

own seed stocks <strong>and</strong> supply contract growers with<br />

planting materials. In some cases, they supply all<br />

the required inputs while producers complement<br />

with l<strong>and</strong>, labor, <strong>and</strong> management.<br />

According to the DA’s SAP for Papaya 2002,<br />

Metro Manila obtains the Cavite Special <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Morado papayas from Cavite <strong>and</strong> Oriental<br />

Mindoro, <strong>and</strong> the Solo papaya from Davao <strong>and</strong><br />

South Cotabato. Also, growers from Davao <strong>and</strong><br />

South Cotabato supply the Solo papaya to other<br />

local supermarkets <strong>and</strong> export markets.<br />

When exporting to Japan, South Korea, <strong>and</strong><br />

New Zeal<strong>and</strong> markets, companies follow<br />

established quarantine protocol for fresh papaya,<br />

which requires a phytosanitary certificate <strong>and</strong> a<br />

vapor heat treatment (VHT).<br />

In the Philippines, one <strong>of</strong> the VHT plants is<br />

located in Panabo, Davao del Norte. It is being<br />

operated by Dole Philippines, Inc. to facilitate fresh<br />

papaya <strong>and</strong> mango exports. For other markets such<br />

as Hong Kong <strong>and</strong> the Middle East, exporters<br />

accomplish phytosanitary certificate only.<br />

Some companies also export fresh <strong>and</strong> dried<br />

papaya. They put fresh papaya in can as fruit<br />

cocktails. TADI <strong>and</strong> Orient Foods, Inc. produce<br />

dried papaya.<br />

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Threats (SWOT) Analysis<br />

The members <strong>of</strong> the National Papaya R&D<br />

Committee 2004 prepared the SWOT analysis on<br />

the Philippine papaya industry.<br />

The SWOT analysis was based on the<br />

available data/information in the DA’s SAP for<br />

Papaya 2002, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Science</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong>-United Nations Development Program<br />

(DOST-UNDP) Gain Export (GAINEX) report,<br />

<strong>and</strong> discussions with experts <strong>and</strong> other industry<br />

stakeholders. Results are shown in Table 6.<br />

12 ............................................................................................................. R&D <strong>Status</strong> <strong>and</strong> Directions

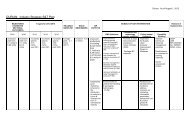

Table 6. SWOT analysis on the Philippine papaya industry.<br />

Strengths Weaknesses<br />

• Available varieties <strong>and</strong> hybrids • Susceptible to pests<br />

• Suitable agroclimatic conditions • Poor technology adoption<br />

• Year-round production • Susceptible to typhoon<br />

• Versatile crop • Inadequate production <strong>and</strong> postproduction<br />

• Varied uses technology<br />

• Highly nutritious • Lack <strong>of</strong> certified seeds<br />

• High domestic <strong>and</strong> export dem<strong>and</strong> • High cost <strong>of</strong> pesticides<br />

• Lack <strong>of</strong> irrigation systems in some growing areas<br />

Opportunities Threats<br />

• Growing domestic <strong>and</strong> export markets • Frequent typhoon occurrence in some growing<br />

• Exp<strong>and</strong>ing product lines (processed, areas<br />

nutraceuticals, papain) • Competition with other fruits<br />

• Biotechnology tools available • Pest problems<br />

• Proximity to export markets • Importer’s preference<br />

• Sanitary <strong>and</strong> phytosanitary trade barriers<br />

Papaya.............................................................................................................................................................. 13

Technological Milestones<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

R&D Investments<br />

The Philippine government invested almost<br />

P32 M for papaya R&D from 1990 to 2003<br />

(Table 7). This amount was only one fifth <strong>of</strong> the<br />

investments made in mango (P171 M) <strong>and</strong> more<br />

than half in banana (P53 M) or in ornamental<br />

horticulture (more than P58 M from 1990 to 2000).<br />

These commodities, including papaya, have<br />

been accorded high priority by DOST under its<br />

<strong>Science</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Technology</strong> Agenda for National<br />

Development (STAND) <strong>and</strong> by DA through its High<br />

Value Commercial Crops (HVCC) Program.<br />

Projects <strong>and</strong> Studies on Papaya<br />

With the government’s investment for papaya R&D,<br />

43 studies were conducted from 1990 to 2003.<br />

The studies focused on varietal improvement (14),<br />

crop production <strong>and</strong> management (11),<br />

crop protection (10), biotechnology (5), postharvest<br />

h<strong>and</strong>ling (2), <strong>and</strong> socioeconomics <strong>and</strong> marketing<br />

(1) (Table 8). Biotechnology studies, however, got<br />

the bulk <strong>of</strong> the budget (74%) followed by studies<br />

on varietal improvement (14%).<br />

Biotechnology projects on papaya came in<br />

1997 as part <strong>of</strong> the DOST-approved biotechnology<br />

Table 7. R&D investment in papaya, mango, <strong>and</strong> banana in the Philippines, 1990–2003 (PCARRD). a<br />

Budget (P)<br />

Year Papaya Mango Banana<br />

1990 1,251,535 1,267,080 2,408,819<br />

1991 646,860 733,632 2,720,652<br />

1992 267,143 490,974 3,223,068<br />

1993 305,400 516,854 1,155,633<br />

1994 279,923 808,323 948,520<br />

1995 54,620 1,810,000 4,152,432<br />

1996 833,257 24,294,978 725,285<br />

1997 583,239 26,697,469 1,385,025<br />

1998 6,935,687 16,852,386 6,358,381<br />

1999 6,088,604 24,625,654 12,605,363<br />

2000 7,523,477 22,353,352 9,965,250<br />

2001 5,735,122 35,252,081 5,437,691<br />

2002 438,147 9,501,840 770,000<br />

2003 709,308 6,239,466 1,658,804<br />

Total 31,652,322 171,444,089 53,514,923<br />

a PCARRD’s Research <strong>and</strong> Development Management Information System (RDMIS).<br />

14 ............................................................................................................. R&D <strong>Status</strong> <strong>and</strong> Directions

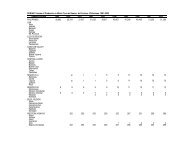

Table 8. Studies on papaya by discipline <strong>and</strong> budget in the Philippines, 1990–2003. a<br />

No. <strong>of</strong><br />

Budget<br />

Discipline Studies Percent (P) Percent<br />

1. Biotechnology 5 12 23,329,722 74<br />

2. Varietal improvement 14 32 4,363,460 14<br />

3. Crop protection 10 23 1,836,920 6<br />

4. Crop production <strong>and</strong> management 11 26 1,558,885 5<br />

5. Postharvest h<strong>and</strong>ling 2 5 548,335 2<br />

6. Socioeconomics <strong>and</strong> marketing 1 2 15,000 0.05<br />

Total 43 100 31,652,322 100.00<br />

a PCARRD’s RDMIS.<br />

program. From 1998 to 2003, there were five<br />

approved biotechnology studies on papaya with<br />

funding from DOST, PCARRD, <strong>and</strong> the Australian<br />

Center for International Agricultural Research<br />

(ACIAR). The support amounted to P23 M.<br />

IPB researchers solely implemented the studies to<br />

produce papaya with resistance to PRSV <strong>and</strong><br />

papaya with delayed ripening characteristics.<br />

Varietal improvement studies on papaya mainly<br />

revolved around collection, evaluation, purification,<br />

<strong>and</strong> hybridization. About 82% <strong>of</strong> the R&D<br />

investment on varietal improvement went to papaya<br />

breeding at IPB. The papaya breeding project<br />

started in 1981 even when PRS was still unheard<br />

<strong>of</strong> (Villegas 1996). During the first phase (1981–<br />

1990), this UPLB-funded project lost a lot <strong>of</strong><br />

breeding lines developed because <strong>of</strong> PRS. Hence,<br />

the project objectives had to be refocused to include<br />

PRSV resistance/tolerance.<br />

PCARRD <strong>and</strong> UPLB funded the second phase<br />

from 1990 to 1995. It came up with a PRSVtolerant<br />

Sinta papaya, which is considered as an<br />

R&D milestone. DOST supported the third phase<br />

(1996–2002). This involved further breeding work<br />

that identified four promising PRSV-tolerant F 1<br />

hybrids <strong>and</strong> adopted micropropagation as an<br />

alternative method to produce planting materials.<br />

Together with this breeding project were other<br />

projects or studies related to PRS. Almost 6% <strong>of</strong><br />

the R&D investments were put to crop protection<br />

(vector control, virus eradication, <strong>and</strong> management<br />

strategies), while 5% went to crop production <strong>and</strong><br />

management. In fact, DOST funded the PCARRDpackaged<br />

papaya rehabilitation <strong>and</strong> development<br />

program in Southern Tagalog <strong>and</strong> in the Bicol region<br />

where PRS had taken its toll on papaya plantations.<br />

Among the R&D efforts, postharvest h<strong>and</strong>ling<br />

(2%) <strong>and</strong> socioeconomics <strong>and</strong> marketing (0.05%)<br />

researches got the least budget from the total<br />

investments. PCARRD funded basic research<br />

on reducing fruit injury <strong>of</strong> the Solo papaya that is<br />

subjected to VHT.<br />

Technological Breakthroughs<br />

<strong>and</strong> Information Generated<br />

The National Agriculture R&D Network<br />

(NARRDN) has reported 13 research findings<br />

on papaya from 1990 to 2003 (Table 9). These<br />

were published in the PCARRD’s R&D Highlights<br />

<strong>and</strong> in the PCARRD-based Horticulture Information<br />

Network (HORTINET) Web site (http://<br />

www.hortinet.pcarrd.dost.gov.ph).<br />

The research findings have generated<br />

information <strong>and</strong> technologies that give significant<br />

development or new knowledge, <strong>of</strong>fer bright<br />

prospect for business, possess significant social <strong>and</strong><br />

economic implications that need to be disseminated<br />

<strong>and</strong> validated under the actual farming situations.<br />

Papaya.............................................................................................................................................................. 15

Table 9. Papaya research findings in the Philippines, 1990–2003. a<br />

Title TM b ACP c ID d TV e<br />

1. Papaya genetic transformation for ringspot virus<br />

resistance (2002)<br />

X<br />

2. Germplasm collection <strong>and</strong> hybridization <strong>of</strong> papaya<br />

(2002) X<br />

3. Papaya varieties tolerant to ringspot virus with<br />

good horticultural traits (1999)<br />

X<br />

4. Isolation/detection <strong>of</strong> virus-like particles in banana,<br />

papaya, <strong>and</strong> citrus (1997)<br />

X<br />

5. Papaya rehabilitation <strong>and</strong> development project in<br />

Southern Tagalog <strong>and</strong> Bicol Region (1997)<br />

6. Modified atmosphere (MA) storage for banana,<br />

papaya, <strong>and</strong> pineapple (1996)<br />

X<br />

7. Papaya rehabilitation <strong>and</strong> development project in<br />

Southern Tagalog/Bicol (1996)<br />

X<br />

8. Hybrid papaya (1995) X X<br />

9. Control <strong>of</strong> PRSV vectors (1993) X<br />

10. Occurrence <strong>and</strong> severity <strong>of</strong> papaya ringspot<br />

disease <strong>and</strong> its vectors<br />

X<br />

11. Reduction <strong>of</strong> fruit injury in Solo papaya (1992) X<br />

12. Control <strong>of</strong> papaya spider mites (1992) X<br />

13. Six promising strains <strong>of</strong> papaya (1990) X<br />

a PCARRD<br />

b <strong>Technology</strong> milestones.<br />

c<br />

Action/Commercialization programs.<br />

d Information for dissemination.<br />

e <strong>Technology</strong> for verification.<br />

Sinta Hybrid<br />

Among the findings, notable is the development<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sinta hybrid at IPB (Villegas et al.<br />

1994). The institute took 14 years (1981–1995) to<br />

develop the hybrid (Villegas 1995).<br />

The dem<strong>and</strong> for growing Sinta papaya has<br />

been increasing because <strong>of</strong> the growers’ desire to<br />

rehabilitate papaya plantings affected by the disease<br />

(Villegas 1996b). Sinta papaya, coupled with<br />

available disease management strategies, is the only<br />

variety that can be pr<strong>of</strong>itably grown in PRSVinfected<br />

areas. Because <strong>of</strong> anticipated dem<strong>and</strong> for<br />

Sinta, a micropropagation technique using nodal<br />

cuttings was also developed to complement seed<br />

production (Villegas et al. 2000).<br />

Based on a serological test, tissue culturederived<br />

Sinta papaya was proven to be virus-free.<br />

This means that the materials can be safely<br />

transported to other areas without bringing the<br />

dreaded virus. Field performance <strong>of</strong> the materials<br />

also showed reduced juvenile period without <strong>of</strong>ftypes.<br />

Four Promising F 1<br />

Hybrids<br />

Another interesting development was the four<br />

promising F 1<br />

hybrids that have high qualities <strong>and</strong><br />

tolerance to PRSV (Villegas 2002). These hybrids<br />

are the two medium-sized, yellow-fleshed hybrids<br />

<strong>and</strong> the medium-sized, red- <strong>and</strong> yellow-fleshed Solo<br />

hybrids. These, however, await further field<br />

evaluation before being released as new varieties.<br />

16 ............................................................................................................. R&D <strong>Status</strong> <strong>and</strong> Directions

Interspecific Hybridization<br />

for PRSV Resistance<br />

IPB researchers also studied the transfer <strong>of</strong><br />

PRSV-resistant genes from wild Carica species<br />

(C. cauliflora, C. pubescens, C. quercifolia, <strong>and</strong><br />

C. stipulata). They employed embryo rescue to<br />

produce the base population. Through manual<br />

pollination, the first backcross generation was<br />

produced containing the PRSV-resistant genes from<br />

C. quercifolia (Siar 2003).<br />

Corollary to this, Mendoza-Garces (2002)<br />

identified morphological, cytological, biochemical,<br />

<strong>and</strong> molecular markers to characterize <strong>and</strong> confirm<br />

the hybridity <strong>of</strong> C. papaya x C. quercifolia F 1<br />

hybrid.<br />

Based on cytological <strong>and</strong> morphological<br />

analyses between C. papaya <strong>and</strong> C. quercifolia<br />

genomes, partial homeology indicates the transfer<br />

<strong>of</strong> useful PRSV-resistant genes from the wild species<br />

(C. quercifolia) to cultivated papaya germplasm as<br />

a result <strong>of</strong> hybridization.<br />

Molecular Markers for Genetic<br />

Diversity Analysis<br />

In view <strong>of</strong> the genetic diversity <strong>of</strong> germplasm<br />

collections on papaya, the papaya collections were<br />

also characterized by using optimized simple<br />

sequence repeats (SSR) protocol. Six SSR primers<br />

(CPY1, CPY2, ACC1, ACC3, BGAL1, <strong>and</strong><br />

BGAL2), developed at UPLB IPB, were used to<br />

characterize genetic diversity among 54 papaya<br />

accessions (Garcia 2002). A partial genetic diversity<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> Philippine papayas was produced with 3<br />

primer pairs <strong>and</strong> 54 papaya accessions.<br />

Genetic Transformation in Papaya<br />

Researchers from IPB have been successful in<br />

inducing somatic embryogenesis in papaya, which<br />

is needed for genetic engineering (Villegas 1996).<br />

On the development <strong>of</strong> PRSV-resistant papaya<br />

from the somatic embryos <strong>and</strong> growing multishoots,<br />

transgenic lines were produced <strong>and</strong> maintained for<br />

screenhouse screening against PRSV (Magdalita<br />

2003). These transgenic lines contain the coat<br />

protein (cp) gene <strong>of</strong> Philippine PRSV isolate, which<br />

was transferred into papaya genome either through<br />

the modified transformation system via particle<br />

bombardment or Agrobacterium-mediated<br />

transformation.<br />

Of the gene transfer technique, the project<br />

adopting the Agrobacterium-mediated<br />

transformation technique is more advanced in<br />

producing R 2<br />

transgenic lines; while the project<br />

adopting the particle bombardment technique has<br />

only produced R 1<br />

transgenic lines.<br />

While developing papaya with delayed ripening<br />

characteristics, R 2<br />

transgenic lines were produced<br />

<strong>and</strong> maintained for greenhouse evaluation<br />

(Mendoza 2003). The transgenic lines contain the<br />

ACC synthase gene (from Davao Solo), which<br />

was transferred to the Solo papaya by using a<br />

gene gun technique. Another technique, using<br />

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, was also<br />

initiated by transferring ACC oxidase gene (local<br />

gene) to papaya genome (Magdalita 2003). The<br />

project adopting the gene gun technique produced<br />

R 2<br />

generations for greenhouse evaluation, while<br />

the project on Agrobacterium-mediated<br />

transformation technique is in the laboratory stage<br />

still regenerating transgenic plants.<br />

Management Strategies Against PRSV<br />

<strong>and</strong> Spider Mites<br />

Researches on crop protection mostly dealt with<br />

basic studies on rational PRSVmanagement<br />

strategies <strong>and</strong> on controlling spider mites.<br />

PRSV is a tiny entity which has flexous<br />

filamentous particles. An isolate <strong>of</strong> it produces<br />

mosaic, mottle, <strong>and</strong> ringspots in papaya.<br />

Aphids are the PRSV vectors. Initially, there<br />

were five that were identified (Bato et. al. 1993).<br />

These are Aphis craccivora Koch (cowpea aphid,<br />

black bean aphid, or indigo aphid; A. gossypii<br />

Glover; Rhopalosiphum maidis Fitch (corn aphid);<br />

Myzus persicae Sulzer (green peach aphid <strong>and</strong><br />

green tobacco aphid); <strong>and</strong> Lipaphis erysimi<br />

Kaltenbach (false cabbage aphid). In 1995, five<br />

more aphids were identified as PRSV vectors.<br />

These are A. glycines (soybean aphid), A. malvae<br />

(cotton aphid), Micromyzus formosanus Tak.<br />

(onion aphid), Macrosiphum solanifolii Ashm.<br />

(potato aphid), <strong>and</strong> A. medicaginis Koch (Sumalde<br />

Papaya.............................................................................................................................................................. 17

et al. 1995). These aphids acquire <strong>and</strong> transmit<br />

virus very quickly through sap feeding. It is still<br />

unknown, however, whether the virus is<br />

transmissible via the seed, but it may be seedborne<br />

(Bajet 1996).<br />

Bato et al. (1993) identified nine natural<br />

enemies <strong>of</strong> aphids. These are coccinelid beetle,<br />

syphid fly, chalcids, braconids, chrysopids,<br />

staphylinids, mirids, hemerobiid, <strong>and</strong><br />

Entomophtora sp. (a fungus).<br />

Scientists use serological assays, mechanical<br />

transmission, electron microscopy, or a mix <strong>of</strong> the<br />

three to detect PRSV-infected papaya. Using<br />

serological assays, scientists confirmed that the<br />

Philippine PRSV is identical to the viruses in<br />

Thail<strong>and</strong>, Australia, Hawaii, <strong>and</strong> Taiwan (Bajet<br />

1996).The PRSV strain was successfully isolated<br />

in zucchini squash (Cucurbita pepo cv. Blackjack)<br />

(Bajet 1997; 1996). Along with okra, corn,<br />

mungbean, eggplant, cucumber, jelly melon,<br />

pumpkin, squash, centrosema, ‘gabi,’ ‘upo,’<br />

‘patola,’ ‘melon-melonan,’ <strong>and</strong> ‘balatong-aso,’<br />

zucchini squash serves as an alternate host <strong>of</strong> the<br />

vectors <strong>and</strong> the virus (Sumalde 1995). The isolate<br />

produced the typical symptoms in both the squash<br />

<strong>and</strong> papaya.<br />

Similarly, the molecular variability <strong>of</strong> PRSV can<br />

be known through cloning <strong>and</strong> deoxyribonucleic acid<br />

(DNA) sequencing (Aquino <strong>and</strong> Valencia 2001).<br />

Based on the entire cp gene sequences, isolates<br />

from Bulacan, Cavite, Quezon, Isabela, <strong>and</strong><br />

Marinduque were identified at 97–98% sequence<br />

homology. Scientists need to further verify isolates<br />

variability <strong>and</strong> dendogram development based on<br />

genetic coefficient to confirm the virus’ genetic<br />

variability.<br />

Planting PRSV-tolerant variety like the Sinta<br />

papaya is one <strong>of</strong> the recommended practices to<br />

manage PRS (Villegas 1996 a <strong>and</strong> b; Sumalde et al<br />

1995; Bato et al. 1993). The Sinta papaya could<br />

only serve as a stopgap measure in the absence <strong>of</strong><br />

resistant varieties. It must be combined with other<br />

disease management strategies such as:<br />

• Roguing or proper disposing <strong>of</strong> infected<br />

plants;<br />

• Controlling the vector by eliminating<br />

alternate hosts;<br />

• Intercropping with taller crops or by<br />

spraying insecticides;<br />

• Isolating plants;<br />

• Subjecting plants into quarantine;<br />

• Conducting proper cultural management<br />

practices such as weeding, fertilization, <strong>and</strong><br />

irrigation during dry season; <strong>and</strong><br />

• Treating papaya as an annual crop rather<br />

than as a perennial crop.<br />

These disease management strategies were<br />

being employed in the papaya rehabilitation <strong>and</strong><br />

development project in Southern Tagalog <strong>and</strong> in<br />

the Bicol region (Sumalde et al. 1997; 1995). The<br />

project also involved information, education, <strong>and</strong><br />

communication (IEC) campaigns through<br />

consultative meetings, training-seminars,<br />

<strong>and</strong> trimedia to enhance awareness <strong>of</strong> papaya<br />

growers on PRSV <strong>and</strong> to strengthen linkages among<br />

concerned stakeholders. The IEC materials <strong>of</strong> this<br />

project were supplemented with other publications<br />

from other researchers in the NARRDN.<br />

In Davao, Pableo et. al. <strong>of</strong> BPI-Davao National<br />

Crops Research <strong>and</strong> Development Center (BPI-<br />

DNCRDC) suggested practical steps to control<br />

spider mites. These include inspection, judicious<br />

spraying with formetana, <strong>and</strong> removal <strong>of</strong><br />

nonfunctional leaves.<br />

Modified Atmosphere (MA) Storage<br />

<strong>and</strong> VHT <strong>of</strong> Solo Papaya<br />

Postharvest Training <strong>and</strong> Resarch Center<br />

(PHTRC) researchers’ findings on the postharvest<br />

h<strong>and</strong>ling <strong>of</strong> papaya focused mostly on the Solo<br />

variety. Serrano (1996) optimized the application<br />

<strong>of</strong> MA storage <strong>of</strong> the Solo papaya to delay ripening<br />

during commercial shipment trials from Misamis<br />

Oriental to Laguna. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, Lizada<br />

et al. (1991) determined the effect <strong>of</strong> VHT on the<br />

ripening characteristics, fruit injury, <strong>and</strong> disease<br />

incidence on the Solo papaya.<br />

18 ............................................................................................................. R&D <strong>Status</strong> <strong>and</strong> Directions

Institutional Capability<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

The institutions involved in papaya researches are<br />

UPLB, Cavite State University , University <strong>of</strong><br />

Southern Mindanao, Leyte State University<br />

(formerly Visayas State College <strong>of</strong> Agriculture),<br />

Bicol University College <strong>of</strong> Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Forestry,<br />

Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University,<br />

BPI, <strong>and</strong> BPI-DNCRDC, <strong>and</strong> DA regional stations.<br />

These agencies implement basic (especially<br />

UPLB) <strong>and</strong> applied (particularly BPI, DA, <strong>and</strong> other<br />

agricultural universities) research projects.<br />

The lack <strong>of</strong> institutional linkages on papaya<br />

R&D <strong>and</strong> weak technology transfer are among the<br />

major concerns.<br />

Papaya.............................................................................................................................................................. 19

R&D Gaps<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

There are several R&D on papaya<br />

that have been conducted <strong>and</strong> have produced<br />

significant findings. Even so, there are still concerns<br />

that need to be addressed. Some are the following:<br />

• PRSV-susceptible Solo papaya. The<br />

Solo papaya, which is currently the<br />

country’s export variety, is susceptible to<br />

PRSV. Also, some export markets do not<br />

prefer its yellow flesh. Hence, a need to<br />

develop a red-fleshed Solo papaya that has<br />

high tolerance to PRSV <strong>and</strong> has delayed<br />

ripening characteristics.<br />

• Lack <strong>of</strong> inbred varieties with desirable<br />

attributes <strong>of</strong> Sinta. Sinta papaya is<br />

acceptable for local consumers because <strong>of</strong><br />

its medium-sized <strong>and</strong> good quality fruits. It<br />

has moderate tolerance to PRSV. Its being<br />

a hybrid, however, requires that a grower<br />

should always buy seeds to continue planting<br />

papaya. Hence, a need to acquire useful<br />

germplasm <strong>and</strong> develop inbred varieties like<br />

that <strong>of</strong> Solo papaya <strong>and</strong> with the desirable<br />

attributes <strong>of</strong> Sinta papaya. With these,<br />

growers can select their desired seeds, plant<br />

more than one seed or seedling per hill, <strong>and</strong><br />

later on select the best plants for papaya<br />

production.<br />

• Lack <strong>of</strong> effective control measures for<br />

insect pests. Other than the five aphid<br />

species that transmit PRSV, there are other<br />

important insect pests that attack papaya.<br />

Their biology, ecology, <strong>and</strong> epidemiology<br />

should be systematically understood, so<br />

that effective control measures could be<br />

implemented.<br />

• Weak management strategies for PRS<br />

<strong>and</strong> bacterial crown rot. The two major<br />

diseases <strong>of</strong> papaya are PRS <strong>and</strong> bacterial<br />

crown rot.<br />

For PRS, there are two ways to reduce<br />

infection to manageable level:<br />

a) Develop tolerant/resistant varieties/<br />

hybrids through conventional breeding<br />

or through biotechnology interventions;<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

b) Develop cropping systems that will<br />

control the aphids.<br />

Bacterial crown rot, however, is also<br />

becoming a major threat to papaya industry.<br />

Therefore, there is a need to conduct basic<br />

management studies <strong>of</strong> this disease,<br />

including host-plant resistance <strong>and</strong> effective<br />

pest management strategies.<br />

• Lack <strong>of</strong> fertilizer <strong>and</strong> water management<br />

program. Papaya is a fast-growing<br />

plant with a shallow root system that<br />

supports a shoot system that continuously<br />

produces huge leaves, numerous flowers,<br />

<strong>and</strong> large fruits.<br />

There is, therefore, a need to<br />

continuously monitor the nutritional status<br />

<strong>and</strong> water requirements <strong>of</strong> the plants for<br />

maximum production. Basic studies should<br />

also be conducted to establish critical<br />

nutrient levels as a guide to a sound <strong>and</strong><br />

efficient fertilization <strong>and</strong> water management<br />

program.<br />

The R&D directions for papaya present a<br />

total systems approach in addressing these<br />

R&D gaps. Also, Appendix 1 summarizes the<br />

state <strong>of</strong> the art for papaya, which includes the<br />

major research, development, <strong>and</strong> extension<br />

(RDE) programs to address papaya R&D<br />

concerns.<br />

20 ............................................................................................................. R&D <strong>Status</strong> <strong>and</strong> Directions