2004 ATS/ERS Definition - Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine

2004 ATS/ERS Definition - Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine

2004 ATS/ERS Definition - Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

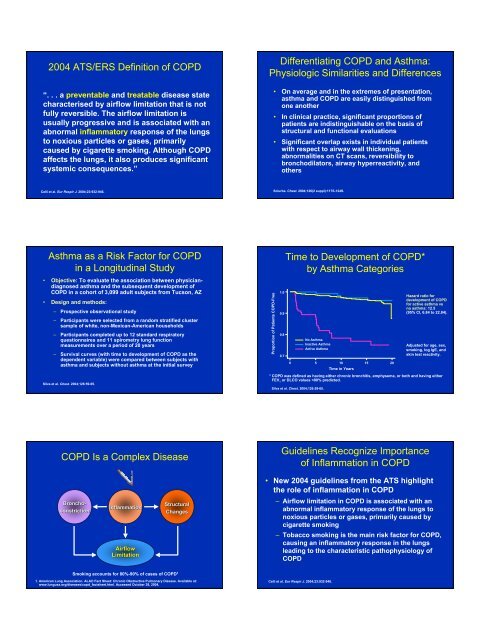

<strong>2004</strong> <strong>ATS</strong>/<strong>ERS</strong> <strong>Definition</strong> of COPD<br />

“. . . a preventable and treatable disease state<br />

characterised by airflow limitation that is not<br />

fully reversible. The airflow limitation is<br />

usually progressive and is associated with an<br />

abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs<br />

to noxious particles or gases, primarily<br />

caused by cigarette smoking. Although COPD<br />

affects the lungs, it also produces significant<br />

systemic consequences.”<br />

Differentiating COPD and Asthma:<br />

Physiologic Similarities and Differences<br />

• On average and in the extremes of presentation,<br />

asthma and COPD are easily distinguished from<br />

one another<br />

• In clinical practice, significant proportions of<br />

patients are indistinguishable on the basis of<br />

structural and functional evaluations<br />

• Significant overlap exists in individual patients<br />

with respect to airway wall thickening,<br />

abnormalities on CT scans, reversibility to<br />

bronchodilators, airway hyperreactivity, and<br />

others<br />

Celli et al. Eur Respir J. <strong>2004</strong>;23:932-946.<br />

Sciurba. Chest. <strong>2004</strong>;126(2 suppl):117S-124S.<br />

Asthma as a Risk Factor for COPD<br />

in a Longitudinal Study<br />

• Objective: To evaluate the association between physiciandiagnosed<br />

asthma and the subsequent development of<br />

COPD in a cohort of 3,099 adult subjects from Tucson, AZ<br />

• Design and methods:<br />

– Prospective observational study<br />

– Participants were selected from a random stratified cluster<br />

sample of white, non-Mexican-American households<br />

– Participants completed up to 12 standard respiratory<br />

questionnaires and 11 spirometry lung function<br />

measurements over a period of 20 years<br />

– Survival curves (with time to development of COPD as the<br />

dependent variable) were compared between subjects with<br />

asthma and subjects without asthma at the initial survey<br />

Silva et al. Chest. <strong>2004</strong>;126:59-65.<br />

Proportion of Patients COPD-Free<br />

1.0<br />

0.9<br />

0.8<br />

0.7<br />

Time to Development of COPD*<br />

by Asthma Categories<br />

No Asthma<br />

Inactive Asthma<br />

Active Asthma<br />

0 5 10 15 20<br />

Time in Years<br />

Silva et al. Chest. <strong>2004</strong>;126:59-65.<br />

Hazard ratio for<br />

development of COPD<br />

for active asthma vs<br />

no asthma: 12.5<br />

(95% CI, 6.84 to 22.84).<br />

Adjusted for age, sex,<br />

smoking, log IgE, and<br />

skin test reactivity.<br />

* COPD was defined as having either chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or both and having either<br />

FEV 1 or DLCO values

Inflammation in COPD<br />

Inflammatory Cells in Subjects<br />

Not Currently Smoking:<br />

Methods<br />

• Objective: Assess the differences in<br />

inflammatory parameters between subjects<br />

with COPD and healthy volunteers<br />

• Sputum induction and bronchoscopy with<br />

BAL and biopsies were performed<br />

• Subjects<br />

– 18 patients with COPD (according to <strong>ATS</strong> criteria)<br />

• 16 had chronic bronchitis<br />

– 11 healthy controls (matched for age and pack-years)<br />

Transverse section of a small airway showing<br />

peribronchiolitis consisting predominantly of lymphocytes<br />

Jeffery. Am J Respir Crit <strong>Care</strong> Med. 2001;164:S28-S38. Official journal of the American Thoracic Society.<br />

©American Lung Association. Reprinted with permission.<br />

Rutgers et al. Thorax. 2000;55:12-18.<br />

Inflammatory Cells in Subjects<br />

Not Currently Smoking:<br />

Methods (cont’d)<br />

• Inclusion criteria<br />

– Impaired lung function in COPD patients<br />

– Negative history of atopy, negative skin tests to<br />

18 common aeroallergens, negative specific<br />

serum IgE for 11 common aeroallergens<br />

– Not current smokers<br />

• 4 subjects with COPD were never smokers<br />

• All other subjects, including healthy controls, had quit<br />

smoking >1 year before study entry<br />

• Inhaled steroids were discontinued<br />

≥1 month before study entry<br />

Rutgers et al. Thorax. 2000;55:12-18.<br />

Sputum Neutrophils (%)<br />

100<br />

90<br />

80<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

Inflammatory Cells in Subjects<br />

Not Currently Smoking<br />

Neutrophils<br />

P=0.0001<br />

Values are expressed as percentages of the total number of nonsquamous cells.<br />

* The role of eosinophils in COPD is not well defined.<br />

Rutgers et al. Thorax. 2000;55:12-18.<br />

Lymphocytes<br />

P=0.0161<br />

Eosinophils*<br />

P=0.0083<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

Sputum Lymphocytes<br />

and Eosinophils (%)<br />

Patients with COPD<br />

Healthy controls<br />

Inflammatory Cells in<br />

Various GOLD Stages of COPD:<br />

Study Design<br />

Inflammatory Cells in<br />

Various GOLD Stages of COPD:<br />

Baseline Characteristics<br />

• Objective: Evaluate the relationship between progression of<br />

COPD (as reflected by GOLD stage) and the pathological<br />

findings in airways

Association Between Total Airway<br />

Wall Thickness and FEV 1<br />

V:SA (mm)<br />

0.25<br />

0.20<br />

0.15<br />

0.10<br />

0.05<br />

GOLD<br />

Stage 4<br />

GOLD GOLD<br />

Stage 3 Stage 2<br />

GOLD<br />

Stages 0 & 1<br />

0.00<br />

0 20 40 60 80 100 120<br />

Small Airway Obstruction in COPD<br />

• Progression of COPD was strongly<br />

associated with increased volume of tissue<br />

in the wall (P

“NETT Lung Transplant and New<br />

Pharmaceuticals for COPD”<br />

James F. Donohue, MD<br />

Professor of <strong>Medicine</strong><br />

&<br />

Chief, Division of <strong>Pulmonary</strong> & <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong><br />

University of North Carolina School of <strong>Medicine</strong><br />

At<br />

Chapel Hill, North Carolina<br />

Number of Transplants<br />

1800<br />

1600<br />

1400<br />

1200<br />

1000<br />

800<br />

600<br />

400<br />

200<br />

0<br />

NUMBER OF LUNG TRANSPLANTS REPORTED<br />

BY YEAR AND PROCEDURE TYPE<br />

Bilateral/Double Lung<br />

Single Lung<br />

408<br />

185<br />

13 15 47 80<br />

685<br />

902<br />

1417 1508 1537<br />

14131410<br />

1342 1337<br />

1206<br />

1069<br />

1985<br />

1986<br />

1987<br />

1988<br />

1989<br />

1990<br />

1991<br />

1992<br />

1993<br />

1994<br />

1995<br />

1996<br />

1997<br />

1998<br />

1999<br />

2000<br />

2001<br />

ADULT LUNG TRANSPLANTATION: Indications (1/1995-6/2002)<br />

DIAGNOSIS<br />

SLT (N = 5,000)<br />

BLT (N = 4,488)<br />

TOTAL (N = 9,488)<br />

LUNG TRANSPLANTATION<br />

Actuarial Survival (Transplants: January 1990 - June 2001)<br />

COPD/Emphysema<br />

IPF<br />

CF<br />

Alpha-1<br />

PPH<br />

Sarcoidosis<br />

Bronchiectasis<br />

Congenital Heart Disease<br />

LAM<br />

Re-TX: OB<br />

OB (Non-ReTX)<br />

Re-TX: Non-OB<br />

Connective Tissue Disorder<br />

Cancer<br />

2,698 ( 54.0% )<br />

1,186 ( 24.0% )<br />

49 ( 1.0% )<br />

429 ( 8.6% )<br />

66 ( 1.3% )<br />

127 ( 2.5% )<br />

11 ( 0.2% )<br />

10 ( 0.2% )<br />

45 ( 0.9% )<br />

47 ( 0.9% )<br />

30 ( 0.6% )<br />

35 ( 0.7% )<br />

21 ( 0.4% )<br />

3 ( 0.1% )<br />

1,000 ( 22.0% )<br />

403 ( 9.0% )<br />

1,447 ( 32.0% )<br />

434 ( 9.7% )<br />

361 ( 8.0% )<br />

113 ( 2.5% )<br />

192 ( 4.3% )<br />

99 ( 2.2% )<br />

58 ( 1.3% )<br />

47 ( 1.0% )<br />

52 ( 1.2% )<br />

37 ( 0.8% )<br />

22 ( 0.5% )<br />

25 ( 0.6% )<br />

3,698 ( 39.0% )<br />

1,589 ( 17.0% )<br />

1,496 ( 16.0% )<br />

863 ( 9.1% )<br />

427 ( 4.5% )<br />

240 ( 2.5% )<br />

203 ( 2.1% )<br />

109 ( 1.1% )<br />

103 ( 1.1% )<br />

94 ( 1.0% )<br />

82 ( 0.9% )<br />

72 ( 0.8% )<br />

43 ( 0.5% )<br />

28 ( 0.3% )<br />

Survival (%)<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

Double lung: 1/2-life = 4.8 Years; Conditional 1/2-life = 8.1 Years<br />

Single lung: 1/2-life = 3.7 Years; Conditional 1/2-life = 5.8 Years<br />

All lungs: 1/2-life = 4.0 Years; Conditional 1/2-life = 6.5 Years<br />

Bilateral/Double Lung (N=6,068)<br />

Single Lung<br />

(N=7,385)<br />

All Lungs<br />

(N=13,453)<br />

p < 0.0001<br />

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12<br />

Years<br />

Histiocytosis X<br />

11 ( 0.2% )<br />

8 ( 0.2% )<br />

19 ( 0.2% )<br />

Other<br />

232 ( 4.6% )<br />

190 ( 4.2% )<br />

422 ( 4.4% )<br />

Smoking Cessation in<br />

Patients with COPD: Results<br />

Rates of Continuous Abstinence from Smoking<br />

Proportion of Patients Abstinent (%)<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Bupropion SR<br />

Placebo<br />

0 5 6 7 10 12 26<br />

Study Week<br />

*P < .05.<br />

Tashkin DP et al. Lancet. 2001;357:1571-1575.<br />

*<br />

* *<br />

*<br />

*<br />

*<br />

(cont)<br />

Mean FEV 1 (L)<br />

2.80<br />

2.75<br />

2.70<br />

2.65<br />

2.60<br />

2.55<br />

2.50<br />

2.45<br />

Lung Health Study: Results<br />

Mean Postbronchodilator FEV 1<br />

for All Participants<br />

SIP<br />

SI + Ipratropium<br />

UC<br />

Follow-Up (Years)<br />

Anthonisen NR et al. JAMA. 1994;272:1497-1505.<br />

Postbronchodilator FEV 1 (L)<br />

Mean Postbronchodilator FEV 1<br />

for Sustained Quitters and<br />

Continuous Smokers Receiving<br />

Smoking Intervention and Placebo<br />

2.9<br />

2.8<br />

2.7<br />

2.6<br />

2.5<br />

Sustained Quitters<br />

Continuing Smokers<br />

2.4<br />

Screen 2 1 2 3 4 5 Screen 2 1 2 3 4 5<br />

Follow-Up (Years)

Effect of Smoking Cessation on the<br />

Lung Function of Participants<br />

in the LHS: Results<br />

• Women who quit had a larger improvement in the first year<br />

compared with men<br />

• Women who continued to smoke had a greater loss of function<br />

than men with comparable smoking rates<br />

• Heavy smokers benefited from quitting more than light smokers<br />

• Baseline respiratory symptoms did not predict change in lung<br />

function<br />

Patients at High Risk of Death After<br />

LVRS: Early NETT Results<br />

• 1033 patients randomized by June 2001<br />

– 69 high-risk patients<br />

• FEV 1 ≤ 20% predicted and either a homogeneous<br />

distribution of emphysema on computed<br />

tomography or a carbon monoxide diffusing<br />

capacity ≤ 20% of predicted<br />

• Among high-risk patients<br />

– 30-day mortality after surgery was 16% vs 0%<br />

among medically treated patients<br />

– Overall mortality 0.43 deaths per person-year vs<br />

0.11 among medically treated patients<br />

Scanlon PD et al. Am J Respir Crit <strong>Care</strong> Med. 2000;161:381-390.<br />

(cont)<br />

National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1075-1083.<br />

(cont)<br />

LVRS: National Emphysema<br />

Treatment Trial<br />

Results<br />

Probability of Death<br />

0.7<br />

0.6<br />

0.5<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.1<br />

Medical Therapy<br />

Surgery<br />

0.0<br />

0 12 24 36 48 60<br />

Months After Randomization<br />

P = .90.<br />

(cont)<br />

Overall mortality rate = 0.11 deaths per person-year in both treatment groups.<br />

National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2059-2073.<br />

Patients (%)<br />

40<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

LVRS: National Emphysema<br />

Treatment Trial<br />

Results<br />

Improvement in Exercise Capacity at 24 Months<br />

LVRS<br />

Medical<br />

Therapy<br />

*<br />

All patients<br />

*<br />

Low EC High EC Low EC High EC<br />

Predominantly Upper-<br />

Lobe Emphysema<br />

*<br />

Predominantly Non–Upper-<br />

Lobe Emphysema<br />

EC = exercise capacity.<br />

(cont)<br />

*P < .05 vs medical therapy.<br />

National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2059-2073.<br />

LVRS: National Emphysema<br />

Treatment Trial<br />

Conclusions<br />

• Overall, LVRS increases the chance of improved exercise capacity, lung function,<br />

dyspnea, and quality of life but does not confer survival advantage vs medical<br />

therapy alone<br />

• Poor candidates for LVRS include<br />

– High-risk patients (ie, those with FEV 1 ≤ 20% predicted and either<br />

homogenous emphysema or carbon monoxide diffusing capacity ≤ 20%<br />

predicted)<br />

– Patients with non–upper-lobe emphysema and high baseline exercise<br />

capacity<br />

• Good candidates for LVRS include patients with predominantly upper-lobe<br />

emphysema and low baseline exercise capacity<br />

National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2059-2073.<br />

Novel and Future Therapies for COPD<br />

Products in Late-Phase<br />

Development<br />

• Bronchodilators<br />

– Tiotropium<br />

– (R,R)-formoterol<br />

• Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4)<br />

inhibitors<br />

– Roflumilast<br />

– Cilomilast<br />

• Combination therapy<br />

– Fluticasone + salmeterol<br />

– Budesonide + formoterol<br />

Products in Early-Phase<br />

Development<br />

• Inflammatory mediators<br />

– Inhibitors of<br />

leukotriene B4,<br />

interleukin-8, and<br />

related chemokines<br />

– Anti–TNF-α agents<br />

• Antioxidants<br />

• Antiproteases<br />

• Retinoids

Tiotropium<br />

• New-generation anticholinergic agent<br />

• Structurally related to ipratropium bromide<br />

• Slow dissociation from the muscarinic M 3 receptor<br />

found on bronchial smooth muscle<br />

• Long duration of action (≈ 24 hours)<br />

• Inhaled as a dry powder<br />

• Suggested first-line maintenance therapy in GOLD<br />

guidelines (stages II-IV)<br />

Tiotropium vs Salmeterol:<br />

Study Objective and Design<br />

• Objective: to compare the efficacy and safety of tiotropium with<br />

salmeterol<br />

• Design: randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, double-dummy,<br />

parallel group study<br />

• 623 patients were randomized to either<br />

– Tiotropium 18 µg q.d.<br />

– Salmeterol 50 µg b.i.d.<br />

– Placebo<br />

• Patients were followed for 6 months<br />

Barnes PJ. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:733-740.<br />

Pauwels RA et al. Available at: http://www.goldcopd.com. Accessed July 15, 2003.<br />

Donohue JF et al. Chest. 2002;122:47-55.<br />

Tiotropium vs Salmeterol: Results<br />

Mean FEV 1 Before and After Administration of<br />

Study Drug<br />

FEV 1 (L)<br />

1.35<br />

1.30<br />

1.25<br />

1.20<br />

1.15<br />

1.10<br />

Donohue JF et al. Chest. 2002;122:47-55.<br />

Tiotropium (n = 202)<br />

Salmeterol (n = 203)<br />

1.05<br />

Day 1<br />

Placebo (n = 179)<br />

1.00<br />

Day 15<br />

Day 169<br />

0.95<br />

-1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12<br />

Time After Administration (Hours)<br />

(cont)<br />

Tiotropium vs Salmeterol: Results<br />

Mean SGRQ Total Score<br />

SGRQ Total Score<br />

47<br />

Salmeterol (n = 187)<br />

46<br />

Placebo (n = 159)<br />

Tiotropium (n = 186)<br />

45<br />

44<br />

43<br />

42<br />

41<br />

40<br />

0 57 113 169<br />

Test Day<br />

SGRQ = St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.<br />

P < .05 for tiotropium vs placebo. Salmeterol vs placebo is not significant. Tiotropium vs<br />

salmeterol is not significant.<br />

Donohue JF et al. Chest. 2002;122:47-55.<br />

Improvement<br />

(cont)<br />

Oral Steroids – Effects on lung function<br />

in acute COPD exacerbation<br />

Forest Plot Showing the Effect of Estimate of Each<br />

Study and Respective 95% Cls<br />

1) Aaron – N Engl J Med 2003<br />

Study (Reference)<br />

Patients, n<br />

Study (Reference)<br />

147 patients in ED – 10 days of oral Prednisone 40mg<br />

-lower relapse<br />

-Increase in FEV 1 34% vs 15% or 0.30liters vs 0.16L with<br />

placebo<br />

Vestbo et al (3)<br />

Weir et al (9)<br />

Pauwels et al (6)<br />

Lung Health Study<br />

Research Group (7)<br />

Renkema et al (10)<br />

290<br />

98<br />

1277<br />

1116<br />

39<br />

3.1 ± 11.4 (-12.8 to 19.0)<br />

-36.3 ± 22.6 (-80.6 to 8.0)<br />

-12.0 ± 14.0 (-39.4 to 15.4)<br />

-2.8 ± 4.03 (-11.0 to 5.4)<br />

-30.0 ± 93.8 (-213.8 to 153.8)<br />

2) Scope Trial<br />

Burge et al (8)<br />

751<br />

-9.0 ± 6.38 (-21.5 to 3.5)<br />

Niewoehner – N Engl J Med 1999<br />

-active treatment – FEV 1 increases 100ml within 24 hours<br />

3) Davies – Lancet 1999<br />

Total 3571<br />

-5.0 ± 3.2 (-11.2 to 1.2)<br />

-300 -200 -100 0 100 200 300<br />

Difference Between Placebo and Treatment Groups in FEV 1 , Decline mL/y

Effect of FP in COPD<br />

• ISOLDE – Run in – Fall of FEV 1 of 75ml on ICS –<br />

89ml FEV 1 fall – not on ICS 47ml<br />

• Oral steroides – 60ml increase in FEV 1<br />

• Rate of decline – 59 verses 50ml<br />

• At 3 and 6 months – 76ml and 100ml higher<br />

• At all points FEV 1 70ml higher with FP<br />

• No relationship to oral CS<br />

Exacerbation in COPD<br />

• Associated with mortality<br />

• Multiple causes – infections, irritants<br />

• Defining event<br />

• Costly – drugs, hospital, loss<br />

• Correlates with Hs QOL<br />

Reduced Risk of Mortality and Repeat<br />

Hospitalization with Inhaled<br />

Corticosteroids<br />

COPD Hospitalization Free Survival<br />

1.0<br />

0.9<br />

0.8<br />

0.7<br />

0.6<br />

No Inhaled Corticosteroids<br />

Inhaled Corticosteroids<br />

0.5<br />

0 2 4 6 8 10 12<br />

Months After Discharge<br />

ICS associated with a 26% lower<br />

relative risk for all-cause mortality<br />

and repeat hospitalization<br />

FP Reduces Median Annual Exacerbation<br />

Rate: ISOLDE Study<br />

Exacerbations/patient/year<br />

1.4<br />

1.2<br />

1<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

1.3<br />

2<br />

Placebo<br />

O.99*<br />

Fluticasone 500mcg<br />

BID<br />

*p=0.026<br />

Adapted from Sin DD, Tu JV. Am J Respir Crit <strong>Care</strong> Med 2001;164:580-584<br />

Burge PS et al. Br Med J. 2000;320:1297-1303<br />

Study Design<br />

ADVAIR 250/50 mcg b.i.d.<br />

p.r.n.<br />

albuterol<br />

Placebo<br />

run-in<br />

Fluticasone propionate 250 mcg b.i.d.<br />

Salmeterol 50 mcg b.i.d.<br />

Placebo b.i.d.<br />

2 weeks<br />

24 weeks<br />

All treatments administered via the DISKUS ® device.<br />

Patients were stratified based on reversibility to albuterol.<br />

Hanania et al. Chest. 2003;124:834-843.

∆ FEV 1 (mL)<br />

200<br />

150<br />

100<br />

50<br />

0<br />

Superior Improvement in Predose FEV 1<br />

Demonstrates Contribution of Fluticasone Propionate<br />

PLA SAL 50 ADV 250/50<br />

(1%)<br />

(9%)<br />

(17%)<br />

-50<br />

Endpoint<br />

0 2 4 6 8 12 16 20 24 (last evaluable FEV 1 )<br />

Time (weeks)<br />

* P

* # * # *<br />

∆ Inspiratory Capacity (L)<br />

Salmeterol reduces dynamic<br />

hyperinflation during exercise in<br />

COPD<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.1<br />

0<br />

*<br />

SLM<br />

PLAC<br />

a<br />

b<br />

c<br />

Effect of salmeterol on mucosal<br />

damage<br />

Epithelial ciliated cells (% surface area)<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

Haemophilus<br />

influenzae<br />

(a) Basal (b) Control (c) Salmeterol<br />

* p=0.002 vs. placebo<br />

Man et al. Thorax <strong>2004</strong><br />

Dowling et al, Eur Respir J 1998<br />

Synergistic interactions between<br />

salmeterol and fluticasone<br />

propionate<br />

Seretide onset of action: Significant<br />

improvement in lung function from day<br />

1<br />

Improvement in<br />

PEF (L/min)<br />

30<br />

Seretide 50/500mcg bd<br />

Salmeterol 50mcg bd<br />

Fluticasone propionate 500mcg bd<br />

20<br />

10<br />

*<br />

0<br />

Day 1 Days 1-14<br />

* p

What do improvements in health<br />

status actually mean for a patient?<br />

A 4 unit improvement in SGRQ<br />

score means that the patient<br />

No longer walks more slowly<br />

than others of their age<br />

and<br />

Is no longer breathless on<br />

bending over<br />

and<br />

Is no longer breathless when<br />

washing and dressing<br />

A 2.7 unit improvement in<br />

SGRQ score means that the<br />

patient<br />

No longer takes a long time<br />

to wash or dress<br />

and<br />

Can now climb a flight of<br />

stairs without stopping<br />

Jones Data on file<br />

Conclusion:<br />

COPD management can be<br />

improved today<br />

• Combination therapy of fluticasone<br />

propionate and salmeterol is an effective<br />

treatment for COPD<br />

– Functional impairement<br />

– Breathlessness<br />

– Health status<br />

• Patient condition can be rapidly improved:<br />

– In a few days for functional impairement and<br />

dyspnea<br />

– In a few weeks for health status<br />

Conclusions: COPD<br />

• Bronchodilators increase time to<br />

exacerbations<br />

• Inhaled corticosteroids reduce<br />

exacerbation rate<br />

• Exacerbation have effects on Hs QOL<br />

• And recovery of pulmonary function