Personality theories of successful aging - University of Florida ...

Personality theories of successful aging - University of Florida ...

Personality theories of successful aging - University of Florida ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Flandbook <strong>of</strong><br />

Gerontology<br />

Evidence-Based Approaches<br />

to Theory, Practice, and Policy<br />

Edited by<br />

fames A. Blackburn/ PhD<br />

Catherine N. Dulmus, PhD<br />

john Wiley & Sons, Inc.<br />

_^'-

This book is printed on acid-free paper. @<br />

Copyright @ 2007 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.<br />

by<br />

l"Plirlr"9 iohn Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.<br />

Published simultaneously in Canada.<br />

Wiley Bicentennial Logo: Richard J. Pacifico<br />

No part <strong>of</strong> this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any<br />

form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise,<br />

except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 <strong>of</strong> the 7976 United States Copyrighi Act, without<br />

either the.prior written permission <strong>of</strong> the Publisher, or authorization throu"gh"payment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

fee<br />

3gf.gp]11t".p_".-1opy<br />

to_the Copyright Clearance Center, rnc.,222 Rosew:ood Drive, Danvers,<br />

MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to<br />

the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions liepaitment, John'Wiley &<br />

sons, Inc., 111 River street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-601,1, f ax (201V48-6008, or online it<br />

http: //www.wiley.com/golpermissions.<br />

To out<br />

Limit <strong>of</strong> Liability/Disclaimer <strong>of</strong> Warranty: Whiie the publisher and author have used their best<br />

efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the<br />

accuracy or completeness <strong>of</strong> the contents <strong>of</strong> this book and specifically disclaim anyimplied<br />

warranties <strong>of</strong> merchantability or fitness for a particular puipose. No-warranty may be created or<br />

extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and itrategies contained<br />

herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a pr<strong>of</strong>essionil where<br />

appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any Ioss bf pr<strong>of</strong>it or any other<br />

commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidenial, consequential, oi other<br />

damages.<br />

This publication is designed to_ provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the<br />

subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not enigaged in<br />

rendering pr<strong>of</strong>essional services. If legal, accounting, medical, psyihological or any oihlr expert<br />

assistance is required, the services <strong>of</strong> a competent pr<strong>of</strong>essionai person ihould be iought.<br />

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are <strong>of</strong>ten claimed as trademarks.<br />

In all instances where John.Wiley & Sons,lnc. is aware <strong>of</strong> a claim, the product names appear in<br />

initial capital or all capital letters. Readers, however, should contact the appropriate companies<br />

for more complete information regarding trademarks and registration.<br />

For general information on our other products and services please contact our Customer Care<br />

Department within the United states at (800) 762-2974. outside the United states at<br />

(377) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.<br />

Wiley also publishes its books.in a variety <strong>of</strong> electronic formats. Some content that appears in<br />

print may not be available in electronic books. For more information about Wiley products, visit<br />

our web site at www.wiley.com.<br />

Library <strong>of</strong> Congress Cataloging-in-Publication<br />

Data:<br />

Handbook <strong>of</strong> gerontology : evidence-based approaches to iheory,<br />

practice, and policy / edited by James A. Blackburn, Catherine N.<br />

Dulmus.<br />

P;cm<br />

Includes bibliographical references.<br />

ISBN-13: 978-0-477-77170-8 (cloth : alk. paper)<br />

1. Ceriatrics-Handbooks, manuais, etc. j. Gerontolosv-Hand_<br />

books, manuais, etc. 3. Evidence-based medicine-Hanltooks,<br />

manuals, etc. L Blackburn, James A., ph. D. II. Dulmus.<br />

Catherine N.<br />

1. Aging-physiology.<br />

^[DNLM:<br />

Aging-psychology.<br />

3. Ceriatrics-methods. 4. Health Policy. 5.'Health-services for<br />

the Aged. WT 104 H2343 20071<br />

RC9s2.55.H395 2007<br />

678.97-dc22<br />

2006027674<br />

Printed in the United States <strong>of</strong> America<br />

10987654321

nomic and methodological<br />

anisms ol euerudaV cotnition<br />

'dnmentnls <strong>of</strong> assessment nnd<br />

rehavioral treatments: An<br />

t guide to psrlcltothern1ty and<br />

I Association.<br />

CHAPTER 4<br />

<strong>Personality</strong> Theories <strong>of</strong><br />

Successful Aging<br />

NATALIE C. EBNER and ALEXANDRA M, FITEUND<br />

N rHrs cHAprER, we combine an action-theoretical view with a life spandevelopmental<br />

perspective on personality and <strong>successful</strong> <strong>aging</strong> to examine the<br />

role <strong>of</strong> goals and goal-related processes for adaptive development. One <strong>of</strong> the<br />

basic assumptions <strong>of</strong> this integration is that goals and goal-related processes motivate,<br />

organize, and direct behavior and development over time. By setting, pursuing,<br />

and maintaining goals, persons can actively shape their development in<br />

interaction with their given physical, cultural-historical, and social living context.<br />

This renders goals and goal-related processes central to personality and <strong>successful</strong><br />

development across the life span as they constitute a link between the<br />

person and his or her life contexts over time.<br />

We start this chapter by defining the concept <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong> deuelopment and<br />

<strong>aging</strong>.Then we outline the concept <strong>of</strong> personality underlying our approach using<br />

McAdams's (1990,1995) model <strong>of</strong> levels <strong>of</strong> personality. This model integrates dispositional<br />

traits, personal concerns and goals, and life narratives as three levels<br />

<strong>of</strong> personality. We discuss the notion <strong>of</strong> goals as personality-in-context by describing<br />

goals as dynamic aspects <strong>of</strong> personality reflecting the interaction <strong>of</strong> a<br />

person with his or her environment over time. Finally, to highlight the role <strong>of</strong><br />

personal goals for <strong>successful</strong> development, we present three prominent conceptual<br />

frameworks <strong>of</strong> developmental regulation: the model <strong>of</strong> selection, optimization,<br />

and compensation (P. B. Baltes & Baltes, 7990), the dual-process model <strong>of</strong><br />

coping (BrandtstZidter& Renner, 1990), and the model <strong>of</strong> primary and secondary<br />

control (Heckhausen & Schulz, 1995).<br />

WHAT IS SUCCESSFUL DEVELOPMENT?<br />

On a very broad level, current life span-developmental psychology <strong>of</strong>ten describes<br />

adaptive (or <strong>successful</strong>) development as a lifelong process <strong>of</strong> generating<br />

new resources as well as adjusting to physical, social, and psychological changes<br />

with the overall aim to simultaneously maximize developmental gains and

88 EvrpENce-BRSt:Il TuEol

<strong>Personality</strong> Theories <strong>of</strong> Successful Aging 89<br />

ensen/ 1996; P. B. Baltes,<br />

Labouvie-Vief, 1981). At<br />

repted set <strong>of</strong> criteria that<br />

laborated by Freund and<br />

lstions regard i ng cri teria<br />

<strong>aging</strong> in particular. P. B.<br />

:cessful <strong>aging</strong> longevity,<br />

:ial competence, procluc-<br />

Similarly, Lawton (1983)<br />

>jective satisfaction with<br />

tppiness or goal achievenotor<br />

behavior, and cogt<br />

as financial or living<br />

ortcomings <strong>of</strong> such lists,<br />

ld be combined, whether<br />

other, and whether the<br />

:ollection to which criteted.<br />

res to defining <strong>successful</strong><br />

characteristics constitut-<br />

; the guiding question <strong>of</strong><br />

(2) process-oriented ap-<br />

:he question What are the<br />

r time? These approaches<br />

sly adapting to changing<br />

rments to fit their needs,<br />

Busch-Rossnagel, 1981).<br />

reeds and capabilities on<br />

:onstraints on the other<br />

Lracterization <strong>of</strong> successspecific,<br />

single criterion.<br />

:-criterion approach that<br />

re only criterion for suc-<br />

'herefore, to understand<br />

in ernpirical studies it is<br />

there is no single def ining<br />

is seen as indicating<br />

d ages well (Neugarten,<br />

rishes between "broad"<br />

mber <strong>of</strong> defining facets.<br />

ng (e.9., Lawton, 7975).<br />

esses the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

tl functioninS;. Her contce,<br />

environmental maspersonal<br />

growth, and<br />

nguish between two dirn<br />

(life satisfaction) and<br />

an emotional dimension (encompassing positive and negative affect; Bradburn,<br />

1969; Campbell, Converse, & Rodgers, 1976; Diener, 1984; Veenhoven, 1991).<br />

These dimensions can be either used in a domain-general way or applied to specific<br />

life domains.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the critiques <strong>of</strong> subjective well-being as the main or even sole criterion<br />

for <strong>successful</strong> development is that it does not explicitly take environmental conditions<br />

into consideration that support <strong>successful</strong> <strong>aging</strong> or the <strong>successful</strong> interaction<br />

between a person and his or her life context (Havighurst, 1963; Lawton,<br />

1989). A multiple-criteria approach, in contrast, aims at an integration <strong>of</strong> subjective<br />

indicators (e.g., personal life satisfaction and happiness) and more objective<br />

indicators (e.g., everyday instrumental competence). These criteria can be either<br />

short term (e.g., last week's happiness) or long term (e.9., meaning and purpose<br />

in life), domain-specific (e.g., satisfaction with financial situation) or general<br />

(e.g., overall life satisfaction), as well as static and with a definite end point (e.g.,<br />

life satisfaction at a given point in time) or dynamic (e.g., change in life satisfaction<br />

over time; Freund & Riediger, 2003).<br />

Taken together, we distinguish four main approaches to conceptualizing <strong>successful</strong><br />

development and <strong>aging</strong>: criteria-oriented, process-oriented, single-criterion, and<br />

multi-criteria approaches. Table 4.1 summarizes these four outlined approaches.<br />

As we pointed out, there is currently no agreement as to which single criterion<br />

or combination <strong>of</strong> criteria best defines <strong>successful</strong> development. One <strong>of</strong> the reasons<br />

for this lack <strong>of</strong> consensus is that there is no generally agreed-upon model <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>successful</strong> development and <strong>aging</strong> that could serve as the basis for such a definition.<br />

Instead, there are numerous theoretical approaches to <strong>successful</strong> development<br />

and even more empirical findings pertaining to more or less specific factors<br />

contributing to adaptive development. Integration <strong>of</strong> these findings is difficult<br />

because studies use different indicators for <strong>successful</strong> <strong>aging</strong>.<br />

It is beyond the scope <strong>of</strong> this chapter to <strong>of</strong>fer a comprehensive, integrative<br />

model <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong> development. Instead, we aim at approaching the topic<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong> <strong>aging</strong> on different levels <strong>of</strong> personality, focusing on the level <strong>of</strong><br />

personal goals and taking different criteria and dimensions into account.<br />

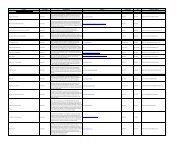

Approach<br />

Table 4.1<br />

Approaches to Conceptualizing Successf ul Development and Aging<br />

Aim <strong>of</strong> Approach (Leading Question)<br />

Criteria-oriented Description <strong>of</strong> characteristics constituting success as an outcome<br />

<strong>of</strong> development ("What ls successf ul development?")<br />

Process-oriented Persoective on individuals as in continuous interaction with their<br />

environment ("What are the processes and conditions that foster<br />

developmental success over time?")<br />

Multiple criteria<br />

Single criterion<br />

Integration <strong>of</strong> subjective and objective indicators ("How can<br />

subjective and objective indicators be integrated into one index <strong>of</strong><br />

successf u I development?")<br />

Assessment <strong>of</strong> a person's global or domain-specific subjective wellbeing<br />

("How can subjective well-being as one indicator <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong><br />

development be assessed [general or domain-specif ic, once or<br />

repeated lyl?")

90 EvrppNcE-BesEp Trrsc-rr

<strong>Personality</strong> Theories <strong>of</strong> Successful Aging<br />

9I<br />

,1987,\997) that (a) deind<br />

that developmental<br />

r gains and losses), and<br />

;es and outcomes serve<br />

rproach. This approach<br />

:r adaptive ways (M. M.<br />

re detail, we posit that<br />

ng the processes <strong>of</strong> suc-<br />

)06). Before elaboratino -a)<br />

bed the concept <strong>of</strong> per-<br />

:y in terms <strong>of</strong> three lev<strong>aging</strong>?<br />

To address this<br />

zli ty. F ollow ing Freund<br />

rn personality and sucs<br />

(1995,1996) compristiongl<br />

trnits. Traits are<br />

nonconditional disposhow<br />

considerable sta-<br />

;. Personal goals are a<br />

:rsonality descriptions<br />

ranisms, copi ng stra tertal,<br />

and strategic conre,<br />

place, and/or social<br />

they integrate and inrconstructed<br />

past, per-<br />

IcAdams (2001), most<br />

lives with unity, purolving<br />

life narratives,<br />

lemes. Level lll <strong>of</strong> perll,<br />

political, economic,<br />

oes the life story <strong>of</strong> a<br />

:vident in the notion<br />

n different contexts"<br />

all <strong>of</strong> these life narra-<br />

, points in life, chance<br />

llowing sections elab-<br />

:sonality traits, that is,<br />

and stable across time<br />

n <strong>of</strong> the stability argufor<br />

a s<strong>of</strong>ter version <strong>of</strong><br />

on personality traits<br />

refers to the identification <strong>of</strong> a universal structure <strong>of</strong> personality, individual differences,<br />

and the extent <strong>of</strong> longitudinal stability (Costa& McCrae, 7994,7995).<br />

There is consensus that personality can be well described by the Big Five personality<br />

traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and<br />

openness to new experiences. These five factors have been identified by means <strong>of</strong><br />

factor analysis across various instruments and samples. Cross-sectional as well as<br />

longitudinal evidence on the structural invariance <strong>of</strong> the Big Five exists for adulthood<br />

and into old age (Costa& McCrae, 1994; Small , Hertzog, Hultsch, & Dixon,<br />

2003). Moreover, according to a meta-analysis by Roberts and DelVecchio (2000),<br />

the rank-order stability <strong>of</strong> the Big Five increases across the life span. These results<br />

were recently supplemented with regard to old and very old age by longitudinal<br />

<strong>aging</strong> studies (Mroczek & Spiro, 2003; Small et al., 2003).<br />

Contrary to some trait personality theorists' view that personality is "set like<br />

plaster" after the age <strong>of</strong> 30 (Costa& McCrae, 7994), cross-sectional as well as longitudinal<br />

evidence on mean levels <strong>of</strong> personality show changes in some <strong>of</strong> the Big<br />

Five characteristics across adulthood. Neuroticism, for example, decreases across<br />

adulthood (Mroczek & Spiro, 2003) and shows some increase again in very old<br />

age (Small et al., 2003). Moreover, in addition to becoming more neurotic, elderly<br />

people tend to become less open to new experiences and less extraverted (Costa,<br />

Herbst, McCrae, & Siegler, 2000), whereas they tend to become slightly more<br />

agreeable and conscientious (Helson & Kwan, 2000).<br />

Summarizing this empirical evidence based on trait as well as growth models <strong>of</strong><br />

personality clearly suggests that personality development in adulthood and old<br />

age is characterized by both stability and change. Regarding the relationship <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Big Five to subjective indicators <strong>of</strong> <strong>aging</strong> well, neuroticism is typically found to be<br />

negatively associated with measures <strong>of</strong> subjective well-being, whereas extraversion<br />

shows a positive relation to well-being. For instance, Isaacowitz and Smith (2003)<br />

demonstrated that in old and very old age (70 to 102 years), neuroticism is linked to<br />

higher negative and lower positive affect. The opposite pattern was found for extraversion<br />

(negative correlation with negative affect, positive correlation with positive<br />

affect). Note, however, that this pattern also holds for younger age groups (e.g., Diener.<br />

1984) and thus does not seem to constitute a deaelopmenfal phenomenon.<br />

Jurrrruc ro LEVEL III: PEnsoNal IpeNtttv<br />

In contrast to dispositional traits, life narratives are heavily influenced by specificities<br />

<strong>of</strong> the context and are subject to change across situations and time.<br />

McAdams (1990) argues that a unified or integrated life story, however, provides<br />

individuals with an identity and allows them to maintain a coherent self-concept<br />

across the entire life span (Cohen, 1998). Life stories are told to different audiences<br />

with different purposes: A life story told to a future spouse might look very<br />

different from the life story told to a future employer, not because the narrator<br />

becomes a different person in between the two events but because different aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> a biography seem important and merit elaboration in these two contexts.<br />

According to McAdams, identity is not derived from one (veridical) life story but<br />

from the very act <strong>of</strong> meaning-making and integration <strong>of</strong> different aspects <strong>of</strong> a life<br />

into one coherent story (albeit possibly a different one each time it is told).<br />

The concept <strong>of</strong> autobiographical memories is closely related to the concept <strong>of</strong><br />

life stories (see also Habermas & Bluck, 2000). Some <strong>theories</strong> on autobiographical

92 EvrpsNcr-BasEpTueoRv<br />

memory (e.g., Pillemer, 7992) hold that it can serve three broad functions: directive<br />

(planning for present and future behaviors), self (self-continuity, psychodynamic<br />

integrity), and social (social bonding, communication; Bluck & Alea, 2002).<br />

The directive function involves using the past during conversations to guide present<br />

and future thought and behavior such as problem solving, developing opinions<br />

and attitudes, or providing flexibility in the construction and updating <strong>of</strong><br />

rules. The self-function provides the ability to support and promote continuity<br />

and development <strong>of</strong> the self and preserves a sense <strong>of</strong> being a coherent person over<br />

time. This function serves to explain oneself to others (and to oneself ). The social<br />

(intimacy or bonding) function, f inally, is important for developing, maintaining,<br />

and nurturing social relationships. This makes us a more believable and persuasive<br />

partner in conversations, provides the listener with information about ourselves,<br />

and allows us to better understand and empathize with others.<br />

Life stories can be related to <strong>successful</strong> development and <strong>aging</strong> in multiple<br />

ways. As pointed out by Erikson (1968),life review becomes a major developmental<br />

task in old age. This life stage, according to Erikson, is characterized by<br />

the two opposite poles <strong>of</strong> "integrity" and "despair." Following Erikson, wisdom<br />

emerges when people are able to accept both the positive and negative events <strong>of</strong><br />

their lives and do not simply gloss over disappointments and failures but are able<br />

to integrate them in a coherent life story together with positive aspects <strong>of</strong> their<br />

past lives. If one understands <strong>successful</strong> <strong>aging</strong> as reaching this point, one might<br />

argue that positivity <strong>of</strong> the life story should not be a criterion <strong>of</strong> <strong>aging</strong> well. Interestingly,<br />

already at midage, it is the theme <strong>of</strong> redemption (i.e., turning a negative<br />

event into a positive one), not a smooth life path filled with positive events, that<br />

is, for instance, related to generativity (i.e., giving to the next generation in some<br />

way; McAdams,2001) as a possible indicator <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong> development.<br />

Another argument could be made for continuity <strong>of</strong> the life story as a milestone <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>successful</strong> development and <strong>aging</strong> (Bluck & Alea, 2002). As it turns out, however,<br />

continuity <strong>of</strong> a life story over time is not necessarily related to positive functioning<br />

in old age. ln a study by Coleman, Ivani-Chalian, and Robinson (1998), a substantial<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> their sample <strong>of</strong> older adults (> 80 years) did not conceive <strong>of</strong> their life<br />

story as a coherent one, but were not necessarily dissatisfied with their present life.<br />

The specific autobiographical memories that are most accessible at a given time<br />

may largely depend on a person's goals. As goal-relevant information is more important<br />

than information not related to personal goals, it is also more likely to be<br />

activated and accessible at a certain time point (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000).<br />

As we will see, personal goals can change over the life span. As a consequence, a<br />

set <strong>of</strong> memories that was once goal-related and self-defining may no longer be so<br />

at a later point in life (Singer & Salovey, 1993). Abandoned earlier goals, however,<br />

can define one's "past self" and thereby provide a psychological history <strong>of</strong><br />

changes in the self. In this way, changes in goals can contribute to life narratives<br />

("What did I use to want in the past, and how did it change over time?").<br />

People construe their self and their identity partially around their personal<br />

goals because goals can <strong>of</strong>fer a sense <strong>of</strong> purpose and meaning in life (Little, 1989)<br />

and provide the possibility for integration <strong>of</strong> otherwise unconnected behaviors<br />

into one unifying frame (Freund, 2006b). As will be elaborated more in the next<br />

sections, personal goals can therefore be seen as part <strong>of</strong> the binding thread that<br />

links the person with his or her context (Freund, 2006b; Little, 1989; McAdams,<br />

1996). This will then clarify how personal concerns and personal goals as Level II<br />

constructs link Level I and Level III.<br />

PERSC<br />

From early on, I<br />

blocks <strong>of</strong> persona<br />

ality, Allport (193<br />

motives as perso<br />

be divorced fron<br />

conduct employt<br />

have the capacit.<br />

tiate responses a<br />

characteristic <strong>of</strong>,<br />

Personal goals ,<br />

tions <strong>of</strong> states a 1<br />

mons/ 1996). They<br />

(1990) suggests lo<br />

tween "being" (i.r<br />

ioral responses ir<br />

That is, goals are<br />

they may be influr<br />

they motivate, str<br />

ingful action unit<br />

Klinger, 7977) an<br />

(cf. Boesch, 7991;<br />

tions in a given r<br />

witzer & Moskow<br />

reduce situationa<br />

As goals are it<br />

Level II <strong>of</strong> personi<br />

<strong>of</strong> personality-inand<br />

his or her eru<br />

the person's basi<br />

or she lives. Spec<br />

processes that sp<br />

crucial in this re1<br />

in the present con<br />

ger , 2006, for a re<<br />

and underlie goal<br />

DrprNrNc CoNrr><br />

Context can be t<br />

person, such as c<br />

environment. It dr<br />

personality, but al<br />

or geographic con<br />

nities in that they<br />

can express his or<br />

siblings may rend

<strong>Personality</strong> Theories <strong>of</strong> Successful Aging 93<br />

broad functions: direclf-continuity,<br />

psychodyon;<br />

Bluck & Alea, 2002).<br />

ersations to guide preslving,<br />

developing opin-<br />

Ltction and updating <strong>of</strong><br />

nd promote continuity<br />

; a coherent person over<br />

I to oneself). The social<br />

:veloping, maintaining,<br />

believable and persua-<br />

.nformation about ourwith<br />

others.<br />

and <strong>aging</strong> in multiple<br />

ts a major developmenn,<br />

is characterized by<br />

wing Erikson, wisdom<br />

and negative events <strong>of</strong><br />

rd failures but are able<br />

rsitive aspects <strong>of</strong> their<br />

;this point, one might<br />

on <strong>of</strong> <strong>aging</strong> well. Intert.e.,<br />

turning a negative<br />

h positive events, that<br />

:xt generation in some<br />

levelopment.<br />

story as a milestone <strong>of</strong><br />

it turns out, however,<br />

:o positive functioning<br />

ln (1998), a substantial<br />

rt conceive <strong>of</strong> their life<br />

with their present life.<br />

essible at a given time<br />

formation is more imalso<br />

more likely to be<br />

)leydell-Pearce,<br />

2000).<br />

.. As a consequence/ a<br />

I may no longer be so<br />

rarlier goals, however,<br />

:hological history <strong>of</strong><br />

rute to life narratives<br />

>ver time?").<br />

round their personal<br />

g in life (Little, 1989)<br />

connected behaviors<br />

ted more in the next<br />

rbinding thread that<br />

Itle, 7989; McAdams,<br />

onal goals as Level II<br />

PERSONAL GOALS: PERSONALITY_IN.CONTEXT<br />

From early on, personality psychology has conceptualized goals as building<br />

blocks <strong>of</strong> personality (Freund& Riediger, 2006).In his dynamic theory <strong>of</strong> personality,<br />

Allport (7937, pp.320-321,) regards<br />

motives as personalized systems <strong>of</strong> tensions, in which the core <strong>of</strong> impulse is not tcr<br />

be divorced from the images, ideas <strong>of</strong> goal, past experience, capacities, and style <strong>of</strong><br />

conduct employed in obtaining the goal. Only individualized patterns <strong>of</strong> motives<br />

have the capacity to select stimuli, to control and direct segmental tensions, to initiate<br />

responses and to render them equivalent, in ways that are consistent with, and<br />

characteristic <strong>of</strong>, the person himself.<br />

Personal goals are <strong>of</strong>ten defined as consciously accessible cognitive representations<br />

<strong>of</strong> states a person wants to achieve, maintain, or avoid in the future (Emmons,<br />

1996). They are relatively consistent across situations and over time. Cantor<br />

(1990) suggests locating goals at an intermediate level <strong>of</strong> personality, the level between<br />

"being" G.e., personality traits, basic dispositions) and "doing" (i.e., behavioral<br />

responses in a given situation), a distinction introduced by Allport (7937).<br />

That is, goals are not as broad and comprehensive as personality traits, although<br />

they may be inf luenced by them. They are also not as specific as behaviors. Rather,<br />

they motivate, structure, and direct behavior over time and situations into meaningful<br />

action units (Baumeister, 1991; Emmons, 1986; Ford,7987; Gollwitzer, 1990;<br />

Klinger, 1977) and favor the acquisition and use <strong>of</strong> resources to obtain the goals<br />

(cf. Boesch, 1991; Freund, 2003). Coals can focus attention on those stimuli and actions<br />

in a given situation that are goal-relevant (Bargh & Ferguson, 2000; Gollwitzer<br />

& Moskowit 2,7996; Kruglanski ,7996; Pervin, 1989). As a consequence, they<br />

reduce situational complexity and facilitate interaction with the environment.<br />

As goals are inherently content- or domain-specific, Little (1989) called this<br />

Level II <strong>of</strong> personality the "personality-in-context." According to Little, the notion<br />

<strong>of</strong> personality-in-context is based on the idea <strong>of</strong> an interaction between the person<br />

and his or her environment over time. Personal goals ref lect the interface between<br />

the person's basic personality traits and the specific environment in which he<br />

or she lives. Specifically, the content a goal refers to as well as the goal-related<br />

processes that specify how people select, pursue, and disengage from goals are<br />

crucial in this regard. Addressing the issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong> development and <strong>aging</strong><br />

in the present context, we do not focus on the content <strong>of</strong> goals (see Freund & Riediger,2006,<br />

for a recent overview) but on the motivational processes that accompany<br />

and underlie goal-related processes and their relations to <strong>successful</strong> development.<br />

DpprrvrNc CoNrExr<br />

Context can be broadly defined as the set <strong>of</strong> circumstances that surrounds a<br />

person, such as culture, historical time, family, social relations, and geographical<br />

environment. It does not only serve as a background for the behavioral expression <strong>of</strong><br />

personality, but also plays an important role in shaping personality. Cultural, social,<br />

or geographic conditions may represent limitations as well as chances and opportunities<br />

in that they exclude or allow certain possibilities <strong>of</strong> whether and how a person<br />

can express his or her basic personality traits. For example, growing up with older<br />

siblings may render a person more agreeable because only by being more agreeable

94 EvrpENce-BasepTuEoRv<br />

might the younger child, constantly lagging behind the older siblings regarding verbal,<br />

cognitive, and motor skills, be able to achieve his or her goals. Contextual constraints<br />

fulfill an important function in that they specify the boundaries without<br />

which personality development would be impossible, as the space <strong>of</strong> possible developmental<br />

trajectories would be too vast and unstructured otherwise.<br />

Life span-developmental psychology (P. g. Baltes, 1987, 7997) provides a useful<br />

framework for understanding how person and context interact over time. This theoretical<br />

framework regards development as a lifelong process <strong>of</strong> flexible adaptation<br />

to changes in opportunities and constraints on biological, social, and<br />

psychological levels (P. B. Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 2006; P. B. Baltes,<br />

Reese, & Lipsitt,1980; Brandtstddter & Lerner, 7999;Bronfenbrenner, l9S8; Lerner<br />

& Busch-Rossnagel, 1981). This assumption has two implications: (1) Individuals<br />

exist in environments that create and define possibilities and limiting bclundaries<br />

for individual pathways; (2) individuals select and create their own living contexts<br />

and thus can play an active part in shaping their lives.<br />

How ro INrrnncr wtrn ONr's CoNlrxr: Goels aNp<br />

Coa l-Rp lerep Pnocnsses<br />

Goals and the basic regulatory processes <strong>of</strong> goal selection, pursuit, and disengagement<br />

are central aspects that help to explain an individual's interaction with his or<br />

her environment (Brandtstddter, 1998; Chapman & Skinner,1985; Emmons, 1986; Freund,<br />

2003, 2006b; Freund & Baltes, 2000; Gollwitzer & Bargh, 1996; Heckhausen/<br />

1999). Goals emerge from and determine the nature <strong>of</strong> people's transactions with the<br />

surrounding world. Experiencing the effects but also the limitations <strong>of</strong> goal-directed<br />

action can feed back to the individual's view <strong>of</strong> the world, the self, personal goals, beliefs<br />

and wishes, and further goal-directed actions. Thus, there is an interplay among<br />

goals, goal-directed actions, and developmental contexts (Brandtstiidter, 1998).<br />

Addressing the contextual nature <strong>of</strong> goals, Freund (2003) distinguishes two interacting<br />

levels <strong>of</strong> representation: social expectations and personal goals. Social<br />

expectations are ref lected in social norms that inform about age-graded opportunity<br />

structures. Age-related social norms can define opportunities and limitations<br />

for developmental trajectories <strong>of</strong> a person's life course. For example, they<br />

indicate the appropriate time to marry and to have children. Thereby, age-related<br />

social expectations or norms can also give an indication about the availability <strong>of</strong><br />

resources in certain life domains for specific age groups (Freund, 2003; Heckhausen,<br />

1999). Setting personal goals in accordance with social norms and expectations<br />

may help to take advantage <strong>of</strong> these available resources. Through social<br />

sanctions as well as approval or disapproval by the society, social expectations<br />

can serve as an orientation or standard for the development, selection, pursuit,<br />

maintenance, and disengagement <strong>of</strong> personal goals (Cantor,7994;Freund,7997;<br />

Nurmi, 1992). Social expectations are also reflected in personal beliefs about the<br />

appropriate timing and sequencing <strong>of</strong> goals, and personal beliefs incorporate individual<br />

values and experiences. Together, social and personal expectations directly<br />

influence behavior and also the personal goals an individual selects and<br />

pursues. This influence can be conscious or unconscious, as, in addition to consciously<br />

represented goals, automatized goals and unconscious motives impact<br />

on behavior and development (Bargh & Ferguson, 2000).<br />

In sum, goals can be viewed as the building blocks <strong>of</strong> personality, person-context<br />

interactions, and lifelong development. The concept <strong>of</strong> personal goals seems particularly<br />

well suited fo<br />

ful <strong>aging</strong> as it allows<br />

furthers our unders<br />

vidual differences ir<br />

particular imPortan<<br />

alternatives and the<br />

goals, also in the fa<br />

prove individual con<br />

for further goal atta.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the basic<br />

developmental Pers<br />

interaction with a 1<br />

actively shaPe their<br />

Ford, 1987; Freund<br />

the person to his or<br />

opment across the I<br />

consider goal selec<br />

goal-related resour<br />

TrtE Rolp oF GoALI<br />

FOR SUCCESSPUT- DE<br />

By nature, human<br />

around the Pursuit<br />

competence, relate<br />

ideal outcomes aga<br />

their progress in tl<br />

ness <strong>of</strong> their goal-r<br />

has shown that Per<br />

Omodei & Wearinl<br />

the mechanisms ul<br />

Processes influenc'<br />

There are differt<br />

<strong>successful</strong> develoP<br />

their goals or reac<br />

1,954; McClelland,<br />

well-being dePend<br />

when these are in<br />

Rogers, 1963; RYan<br />

authors argue tha<br />

(Brunstein, Schult<br />

goals themselves t<br />

related to life sa<br />

Rothermund (2002<br />

argue that neither<br />

<strong>successful</strong> develoP<br />

depression if theY<br />

Thus, setting at<br />

important self-reg<br />

& Renner,7990;C

<strong>Personality</strong> Theories <strong>of</strong> Successful Aging 95<br />

:r siblings regarding verrr<br />

goals. Contextual conthe<br />

boundaries without<br />

l space <strong>of</strong> possible develrtherwise.<br />

1997) provides a useful<br />

'ract over time. This thercess<br />

<strong>of</strong> flexible adaptabiological,<br />

social, and<br />

nger,2006; P. B. Baltes,<br />

enbrenner, 1988; Lerner<br />

cations: (1) Individuals<br />

Lnd limiting boundaries<br />

heir own living contexts<br />

pursuit, and disengage-<br />

; interaction with his or<br />

985; Emmons , 1986; Frergh,<br />

7996; Heckhausen,<br />

l's transactions with the<br />

itations <strong>of</strong> goal-directed<br />

r self, personal goals, bere<br />

is an interplay among<br />

ndtstiidter, 1998).<br />

;) distinguishes two inpersonal<br />

goals. Social<br />

tt age-graded opportu-<br />

,ortunities and limitarse.<br />

For example, they<br />

n. Thereby, age-related<br />

bout the availability <strong>of</strong><br />

(Freund, 2003; Hcckrcial<br />

norms and expcc-<br />

)urces. Through social<br />

ty, social expectations<br />

:nt, selection, pursuit,<br />

>r,7994; Freund, 1997;<br />

sonal beliefs about the<br />

beliefs incorporate insonal<br />

expectations dindividual<br />

selects and<br />

as, in addition to conicious<br />

motives impact<br />

rnality, person-context<br />

nalgoalseems partic-<br />

ularly well suited for a developmental approach to personality <strong>theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong><br />

<strong>aging</strong> as it allows integrating motivational processes into a life span context and<br />

furthers our understanding <strong>of</strong> both the direction <strong>of</strong> development and <strong>of</strong> interindividual<br />

differences in the leuel <strong>of</strong> functioning in various life domains over time. Of<br />

particular importance in this regard is the selection <strong>of</strong> goals from a pool <strong>of</strong> possible<br />

alternatives and the investment <strong>of</strong> resources into the pursuit and maintenance <strong>of</strong><br />

goals, also in the face <strong>of</strong> setbacks and losses. Goal selection and pursuit can improve<br />

individual competences and generate new resources, which can then be used<br />

for further goal attainment.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the basic assumptions <strong>of</strong> joining an action-theoretical with a life spandevelopmental<br />

perspective in personality <strong>theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong> <strong>aging</strong> is that, in<br />

interaction with a given physical, cultural-historical, and social context, people<br />

actively shape their own developmental context (Brandtstiidter & Lerner, 7999;<br />

Ford, 1987; Freund & Baltes, 2000; Lerner & Busch-Rossnagel, 1981). Goals link<br />

the person to his or her life contexts and thus are central to personality and development<br />

across the life span. In the following, we introduce three approaches that<br />

consider goal selection, initiation <strong>of</strong> goal-related actions, and the investment <strong>of</strong><br />

goal-reiated resources as crucial for achieving desired developmental outcomes.<br />

TuE Rolr or Conr.s aNp GonI-RELATED PRocessgs<br />

roR Succsssr-'u r. Duv pI-oPMENT<br />

By nature, human beings are goal-oriented organisms. They organize their lives<br />

around the pursuit <strong>of</strong> goals that reflect their fundamental needs (e.9., autonomy,<br />

competence, relatedness; Ryan, 1995). Goals provide persons with standards and<br />

ideal outcomes against which they can evaluate their actual level <strong>of</strong> functioning,<br />

their progress in the direction <strong>of</strong> higher levels <strong>of</strong> functioning, and the effectiveness<br />

<strong>of</strong> their goal-related behaviors (Carver & Scheier, 1990). Empirical evidence<br />

has shown that personal goals are positively related to well-being (Emmons,7986;<br />

Omodei & Wearing, 1990; Palys & Little, 1983; Sheldon & Elliot, 1999). What are<br />

the mechanisms underlying this relation? That is, how do goals and goal-related<br />

processes inf luence well-being and <strong>successful</strong> <strong>aging</strong>?<br />

There are different views on hor,v goals affect well-being. Tt is <strong>of</strong>ten argued that<br />

<strong>successful</strong> development implies that individuals succeed in progressing toward<br />

their goals or reaching desired states (M. M. Baltes & Carstensen, 1996; Maslow,<br />

1954; McClelland, 1987). Humanistic psychology proposes that a person's sense <strong>of</strong><br />

well-being depends on the person's progress toward his or her goals, especially<br />

when these are in accord with "organismic" or "innate" needs (Maslow, 1954;<br />

Rogers, 1963; Ryan, 1995; see also Brunstein, Schultheiss, & Crdssman, 1998). Other<br />

authors argue that having goals can in itself be a predictor <strong>of</strong> life satisfaction<br />

(Brunstein, Schultheiss, & Maier, 1999; Emmons, 7996). Still others posit that not<br />

goals themselves but rather the al'ailability <strong>of</strong> goal-related resources is positively<br />

related to life satisfaction (Diener & Fujita, 1995). Finally, Brandtstddter and<br />

Rothermund (2002) maintain that goals can ambivalently affect well-being. They<br />

argue that neither goals nor resources themselves bring about goal attainment or<br />

<strong>successful</strong> development. In fact, unattainable goals can lead to dissatisfaction and<br />

depression if they are not abandoned or readjusted.<br />

Thus, setting and pursuing challenging but attainable goals and standards are<br />

important self-regulatory processes conducive to <strong>successful</strong> <strong>aging</strong> (Brandtsttidter<br />

& Renner, 1990; Carver & Scheier, 7981,7982; Freund & Baltes,2000; Heckhausen,

96 EvrppNcr:-BesppTueorrv<br />

1999). In addition, diseng<strong>aging</strong> from goals that are no longer attainable, restructuring<br />

goals, and reallocating goal-related resources into alternative goals and<br />

goal domains are facets <strong>of</strong> adaptive functioning (Klinger, 1975; Wrosch & Heckhausen,1999).<br />

To elaborate further on the idea that personal goals and goal-related processes<br />

are central for <strong>successful</strong> development and to understand better the underlying<br />

mechanisms <strong>of</strong> the relationship between goals and well-being, we introduce three<br />

current self-regulatory <strong>theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> adaptive development in the following part <strong>of</strong><br />

this chapter. All three <strong>theories</strong> view development as multidirectional, comprising<br />

gains and losses across the entire life span. They refer to personal goals and basic<br />

goal-related processes such as setting, pursuing, reformulating, and diseng<strong>aging</strong><br />

from goals as means to <strong>successful</strong>ly shape individual development. All three<br />

frameworks converge in their assumption that resources are Iimited throughout<br />

life, and increasingly so in old age, and that <strong>successful</strong> developmental regulation<br />

requires suitable mechanisms for allocation <strong>of</strong> these limited resources. The three<br />

<strong>theories</strong> vary, however, in their particular focus (e.g., on life span strategies and<br />

personal goals, coping processes, and control processes), in their particular characteristics<br />

<strong>of</strong> the proposed mechanism <strong>of</strong> resource allocation, as well as in their<br />

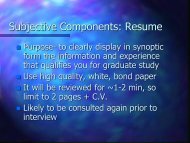

postulated generality. Table 4.2 summarizes the three theoretical frameworks.<br />

Table 4.2<br />

Goal-Related Theories <strong>of</strong> Successful Aging<br />

Theoretical Framework Central Strateoies Specif ic Examples<br />

Model <strong>of</strong> Selection,<br />

Optimization, and<br />

Compensation<br />

Dual-Process Model <strong>of</strong><br />

Assimilative and<br />

Accommodative Coping<br />

Model <strong>of</strong> Optimization in<br />

Primary and Secondary<br />

Control<br />

Selection<br />

Optimization<br />

Compensation<br />

Assimilative coping<br />

Accommodative coping<br />

Selective primary<br />

control<br />

Compensatory primary<br />

control<br />

Selective secondary<br />

control<br />

Compensatory<br />

secondary control<br />

Focusing on Spanish as a foreign<br />

ranguage<br />

Investing more time to improve<br />

Spanish-language skills<br />

Hiring a translator when traveling<br />

in Spain<br />

Altering dietary habits to attain<br />

the desired bodily appearance<br />

Accepting your physical state and<br />

giving up the goal to run the<br />

marathon after knee surgery<br />

Seeing each other more f requently<br />

to improve the relationship<br />

Seeing a marriage guidance counselor<br />

to improve the relationship<br />

Regarding the current partner as<br />

the "only love <strong>of</strong> life"<br />

Regarding the former partner as<br />

a "wrong choice" af ter the<br />

relationship ends<br />

TrrsoRrrtcel<br />

THE }<br />

A<br />

MI<br />

UNDE<br />

Assu<br />

The model <strong>of</strong> selec<br />

eral, metatheoretir<br />

P. B. Baltes,7997;P<br />

It assumes a dYna<br />

stages <strong>of</strong> life (chik<br />

different levels <strong>of</strong> I<br />

ferent domains <strong>of</strong><br />

regulation). In the<br />

source generation<br />

processes bY addr<br />

tioning. As such, S<br />

that helP to manal<br />

ory proPoses thre<br />

ment: selection, opt<br />

have various Poss<br />

(e.g., cognition, sc<br />

vary along the <<br />

unconscious (Fret<br />

At the most ger<br />

ization or canaliz<br />

Selection includes<br />

ternative develoP<br />

limited resource<br />

through this conc<br />

evolve. Thus, sel<br />

sources (P. B. Bal<br />

losses in resource<br />

Optimizatron rc<br />

nance <strong>of</strong> internal<br />

els <strong>of</strong> functionir<br />

achieving higher<br />

pertise. ExPertis<br />

achieved onlY tt<br />

Krampe, & Tesch<br />

ComPensatrcnr<br />

functions in Prer<br />

gains nnd losses i<br />

ful <strong>aging</strong> needs<br />

model does this I<br />

encountering a l<<br />

in the face <strong>of</strong> lost<br />

The SOC thec<br />

tives, such as soc

<strong>Personality</strong> Theories <strong>of</strong> Successful Aging 97<br />

rger attainable, restruc,<br />

o alternative goals and<br />

1975; Wrosch & Heck-<br />

I goal-related processes<br />

I better the underlying<br />

ing, we introduce three<br />

n the following part <strong>of</strong><br />

Cirectional, comprising<br />

ersonal goals and basic<br />

ating, and diseng<strong>aging</strong><br />

levelopment. All three<br />

rre limited throughout<br />

relopmental regulation<br />

ld resources. The three<br />

ife span strategies and<br />

r their particular charion,<br />

as well as in their<br />

retical frameworks.<br />

'lg<br />

lecific Examples<br />

on Spanish as a foreign<br />

Trore time to improve<br />

rnguage skills<br />

anslator when traveling<br />

etary habits to attain<br />

1 bodily appearance<br />

your physical state and<br />

he goal to run the<br />

rfter knee surgery<br />

;h other more f requently<br />

the relationship<br />

larriage guidance coun-<br />

)rove the relationship<br />

the current partner as<br />

rve <strong>of</strong> life"<br />

the former partner as<br />

hoice" af ter the<br />

) ends<br />

THE MODEL OF SELECTION, OPTIMIZATION,<br />

AND COMPENSATION: A GENERAL,<br />

METATHEORETICAL FRAMEWORK FOR<br />

UNDERSTANDING ADAPTIVE DEVELOPMENT<br />

TutonprrceL Assu M pt'toNS<br />

The model <strong>of</strong> selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC) constitutes a general,<br />

metatheoretical framework for understanding human development (e.9.,<br />

P. B. Baltes, 1997;P. B. Baltes & Baltes, 7980,7990; P. B. Baltes, Freund, & Li,2005).<br />

It assumes a dynamic between developmental gains and losses across various<br />

stages <strong>of</strong> life (childhood, adolescence, adulthood, old age) that is represented at<br />

different levels <strong>of</strong> analysis (e.g., neuronal, behavioral) and within and across different<br />

domains <strong>of</strong> functioning (e.g., physical or cognitive development, emotion<br />

regulation). In the context <strong>of</strong> SOC theory, life span development is a process <strong>of</strong> resource<br />

generation and regulation. This theory describes general developmental<br />

processes by addressing both the direction <strong>of</strong> development and the leael <strong>of</strong> functioning.<br />

As such, SOC is a model <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong> development, specifying processes<br />

that help to manage changing resources over the life span. In particular, the theory<br />

proposes three fundamental and universal processes <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong> development:<br />

selection, optirnization, and compensatiotr. All three processes are proposed to<br />

have various possible phenotypic realizations depending on functional domains<br />

(e.g., cognition, social), sociocultural contexts, and person-specific features that<br />

vary along the dimensions active-passive, internal-external, and consciousunconscious<br />

(Freund, Li, & Baltes,7999).<br />

At the most general level <strong>of</strong> definition, selection refers to the process <strong>of</strong> specialization<br />

or canalization <strong>of</strong> a particular pathway or set <strong>of</strong> pathways <strong>of</strong> development.<br />

Selection includes the delineating and narrowing down <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> possible alternative<br />

developmental trajectories. Selection also serves the management <strong>of</strong><br />

limited resources by concentrating resources on delineated domains. Only<br />

through this concentration can specification occur and certain skills and abilities<br />

evolve. Thus, selection is a general-purpose mechanism to generate new resources<br />

(P. B. Baltes et al., 2005). Selection can occur electiaely or as a response to<br />

losses in resources (i.e., Ioss-based).<br />

Optinizatiot'L refers to the acquisition, application, coordination, and maintenance<br />

<strong>of</strong> internal and external resources (means) involved in attaining higher levels<br />

<strong>of</strong> functioning (Freund & Baltes, 2000). Optimization is important for<br />

achieving higher levels <strong>of</strong> functioning, as has been shown in the literature on expertise.<br />

Expertise, a high skill level in a selected functional domain, can be<br />

achieved only through a substantial amount <strong>of</strong> deliberate practice (Ericsson,<br />

Krampe, & Tesch-Romer,7993; Krampe & Baltes,2003).<br />

Compensntion refers to the investment <strong>of</strong> means to avoid or counteract losses in<br />

functions in previously available resources. Given that development entails both<br />

gains and losses across the entire life span (P. B. Baltes , 7987), a model <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong><br />

<strong>aging</strong> needs to take processes <strong>of</strong> man<strong>aging</strong> losses into account. The SOC<br />

model does this by including loss-based selection (referring to reorientation after<br />

encountering a loss) and compensation (aimed at the maintenance <strong>of</strong> functioning<br />

in the face <strong>of</strong> losses).<br />

The SOC theory can be approached from many different theoretical perspectives,<br />

such as social, behavioral-learning, cognitive, and neuropsychological (M. M.

98 EvropNcE-BesppTHectnv<br />

Baltes & Carstensen,1996; P. B. Baltes et a1.,2005; P. B. Baltes & Singer,2001). Freund<br />

and Baltes (2000) propose an action-theoretical conceptualization <strong>of</strong> SOC. This<br />

approach embeds SOC in the context <strong>of</strong> active life-management and refers to developmental<br />

regulation through the selection, pursuit, and maintenance <strong>of</strong> personal<br />

goals.<br />

From an action-theoretical perspective, selectiotr denotes processes related to<br />

goal setting. Electiae selection refers to developing and choosing a subset <strong>of</strong> goals<br />

out <strong>of</strong> multiple options. Given the finite nature <strong>of</strong> resources, selection needs to<br />

take place to realize developmental potentials. Loss-based selection refers to adapting<br />

existing or developing new goals to fit losses in resources. Restructuring<br />

one's goal hierarchy by exclusively focusing on the most important goal, Iowering<br />

one's aspiration level, or finding a substitution for unattainable goals are possible<br />

manifestations. From an action-theoretical perspective, optimization and compensation<br />

refer to processes <strong>of</strong> goal pursuit, that is, the investment <strong>of</strong> resources<br />

into obtaining and refining goal-relevant means. Optimization refers to means for<br />

achieving desired outcomes and aims at coordination, acquisition, and generation<br />

<strong>of</strong> new resources or skills, serving the growth aspect <strong>of</strong> development. Compensation,<br />

from an action-theoretical perspective, addresses the regulation <strong>of</strong> loss or<br />

decline in means and goal-relevant resources that threatens the maintenance <strong>of</strong> a<br />

given level <strong>of</strong> functioning. When previous goal-relevant means are no longer<br />

available, compensation can involve substitution <strong>of</strong> lost means. It thus denotes a<br />

strategy for man<strong>aging</strong> and counteracting losses by changing goal-relevant means<br />

to attain a certain goal instead <strong>of</strong> choosing another goal (as in loss-based selection).<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> hearing aids to counteract hearing losses is one example. Phenotypically,<br />

the strategies used for optimization and compensation, such as<br />

acquisition and practice <strong>of</strong> skills, energy and time investment, or activation <strong>of</strong><br />

new or unused resources, can overlap.<br />

The theory states that the use <strong>of</strong> SOC strategies changes over the life span as a<br />

function <strong>of</strong> available resources. The expected peak <strong>of</strong> expression <strong>of</strong> all three regulatory<br />

principles is in adulthood, with elective selection and compensation increasing<br />

in importance with advancing age when resource losses become more<br />

salient (Freund & Baltes, 2002b).<br />

Aoaplrve DEvplopvgNr as ENpoRSEMENT oF THE Mopal ol Snr-ecrroN.<br />

OptrHarzarroN, ANI) Col,rrnxsa'noN Tr{Roucuout LrrE<br />

Several studies provide evidence for the role <strong>of</strong> SOC in the description, explanation,<br />

and modification <strong>of</strong> development and support their impact on adaptive lifemanagement<br />

(see P. B. Baltes et aL.,2005, for an overview). Evidence suggests that<br />

the relative prevalence <strong>of</strong> using and coordinating SOC changes with age and that<br />

people who engage in SOC behaviors show more positive outcomes. The existing<br />

research comprises different empirical specifications referring to global levels<br />

and specific life contexts. It encompasses different assessment levels such as selfreport<br />

measures (P. B. Baltes, Baltes, Freund, & Lang, 1999), behavior observation<br />

(".9., M. M. Baltes, 7996), and experimental studies (e.g., Li, Lindenberger, Freund,<br />

& Baltes, 2001). Some approaches simultaneously investigate all three components<br />

<strong>of</strong> SOC as well as their orchestration (e.g., Riediger, Li, & Lindenberger,<br />

2006), whereas others focus on some <strong>of</strong> the processes only (e.g., Ebner, Freund, &<br />

Baltes, 2006; Freund, 2006a).<br />

Addressing the c<br />

edge <strong>of</strong> SOC as stri<br />

identified a bodY o<br />

are represented in<br />

human life as exprr<br />

proverb "You can't<br />

proverbs were use(<br />

tions <strong>of</strong>, or preferet<br />

SOC model. In a <<br />

SOC-related and a<br />

life-management si<br />

more frequently ar<br />

theory, these PrefeI<br />

in tasks referring tr<br />

leisure. This sugge<br />

SOC-related prove<br />

and that their judgt<br />

in line with what tl<br />

To investigate tl<br />

adaptive life-manal<br />

the SOC questionr<br />

(2002b) investigate<br />

adults and found I<br />

haviors reported t<br />

being. The associ<br />

variables such as tt<br />

teristics such as ne<br />

expected, SOC-rel<br />

hood; that is, mit<br />

younger and older<br />

positive age trend.<br />

less use <strong>of</strong> oPtimiz<br />

mization and com<br />

strategies are effor<br />

sources available il<br />

ple suffering from<br />

SOC questionnairr<br />

(1998) showed thal<br />

adults betweenT2<br />

strategies also shc<br />

tive affect, satisfac<br />

Wiese and collt<br />

model to goal pu<br />

questionnaire stu<br />

haviors <strong>of</strong> younge<br />

specifically. High<br />

strategies was Pot<br />

nal data replicate<br />

ment in SOC beh;

<strong>Personality</strong> Theories <strong>of</strong> Successfttl Aging 99<br />

Ites & Singer,2001). Frertualization<br />

<strong>of</strong> SOC. Th is<br />

ment and refers to develmaintenance<br />

<strong>of</strong> personal<br />

tes processes related to<br />

losing a subset <strong>of</strong> goals<br />

rces, selection needs rcr<br />

selection refers to adapt-<br />

)sources. Restructuring<br />

nportant goal, lowering<br />

nable goals are possible<br />

optimization and comnvestment<br />

<strong>of</strong> resources<br />

tion refers to means for<br />

risition, and generation<br />

levelopment. Compensa-<br />

Le regulation <strong>of</strong> loss or<br />

ts the maintenance <strong>of</strong> a<br />

: means are no longer<br />

eans. It thus denotes a<br />

rg goal-relevant means<br />

fas in loss-based selecis<br />

one example. Phenormpensation,<br />

such as<br />

:ment, or activation <strong>of</strong><br />

i over the life span as a<br />

ession <strong>of</strong> all three regand<br />

compensation ine<br />

losses become more<br />

,F SELECTION,<br />

description, explanarpact<br />

on adaptive lifelvidence<br />

suggests that<br />

Lges with age and that<br />

utcomes. The existing<br />

rring to global levels<br />

:nt levels such as selfbehavior<br />

observation<br />

,i, Lindenberger, Frestigate<br />

all three com-<br />

', Li, & Lindenberger,<br />

).9., Ebner, Freund, &<br />

Addressing the question whether there exists cultural and individual knowledge<br />

<strong>of</strong> SOC as strategies <strong>of</strong> <strong>successful</strong> development, Freund and Baltes (2002a)<br />

identified a body <strong>of</strong> proverbs reflecting SOC. This suggests that SOC strategies<br />

are represented in cultural knowledge about pragmatic aspects <strong>of</strong> everyday<br />

human life as expressed in proverbs. Selection, for instance, is expressed in the<br />

oroverb "You can't have the cake and eat it too." In a series <strong>of</strong> studies, these<br />

proverbs were used to examine whether younger and older adults' lay conceptions<br />

<strong>of</strong>, or preferences for, life-management behaviors were consistent with the<br />

SOC model. In a choice-reaction time task, participants wele asked to match<br />

SOC-related and alternative proverbs to sentence stems indicative <strong>of</strong> everyday<br />

life-management situations. Both age groups chose SOC-related proverbs both<br />

more frequently and faster than alternative proverbs. Consistent with the SOC<br />

theory, these preferences for SOC-related proverbs over alternatives existed only<br />

in tasks referring to goals and success, but not in contexts involving relaxation or<br />

leisure. This suggests that both younger and older adults have a preference for<br />

SOC-related proverbs over alternatives in everyday life-management situations<br />

and that their judgment <strong>of</strong> the adaptive use <strong>of</strong> these life-management strategies is<br />

in line with what the SOC model proPoses.<br />

To investigate the impact <strong>of</strong> a person's self-reported engagement in SOC on<br />

adaptive life-management and <strong>successful</strong> <strong>aging</strong>, several studies used versions <strong>of</strong><br />

the SOC questionnaire developed by P. B. Baltes et al. (1999). Freund and Baltes<br />

(2002b) investigated a heterogeneous sample <strong>of</strong> younger, middle-aged, and older<br />

adults and found that participants who indicated high engagement in SOC behaviors<br />

reported more positive emotions and higher levels <strong>of</strong> subjective wellbeing.<br />

The associations remained stable after controlling for self-regulation<br />

variables such as tenacious and flexible goal pursuit as well as for person characteristiCs<br />

such as neuroticiSm, extraversion, and Openness tO new experiences. As<br />

expected, SOC-related strategies were most strongly expressed in middle adulthood;<br />

that is, middle-aged adults showed higher endorsement <strong>of</strong> SOC than<br />

younger and older adults. One exception was elective selection, which showed a<br />

positive age trend. This suggests that older adults are more selective but report<br />

less use <strong>of</strong> optimization and compensation. This weakening <strong>of</strong> self-reported optimization<br />

and compensation in older ages could be due to the fact that these two<br />

strategies are effortful and resource demanding. Both strategies may exceed resources<br />

available in late life. This is especially true for the oldest old and for people<br />

suffering from severe illness (P. B. Baltes & Smith, 2003;Jopp,2002)' Using the<br />

SOC questionnaire in the context <strong>of</strong> the Berlin Aging Study, Freund and Baltes<br />

(1998) showed that SOC is effective well into very old age. They found that older<br />

adults between 72 and 102 years who reported more engagement in SOC-related<br />

strategies also showed higher expressions <strong>of</strong> subl'ective well-being such as positive<br />

affect, satisfaction with <strong>aging</strong>, lack <strong>of</strong> agitation, and absence <strong>of</strong> loneliness.<br />

Wiese and colleagues (Wiese, Freund, & Baltes, 2000,2002) applied the SOC<br />

model to goal pursuit in the work and family domains. In a cross-sectional<br />

questionnaire study, Wiese et al. (2000) measured self-reported use <strong>of</strong> SOC behaviors<br />

<strong>of</strong> younger to middle-aged pr<strong>of</strong>essionals in general as well as domainspecifically.<br />

Higher endorsement <strong>of</strong> general and work- and family-related SOC<br />

strategies was positively related to various indicators <strong>of</strong> well-being. Longitudinal<br />

data replicated these positive associations between self-reported engagement<br />

in SOC behaviors and global as well as work-related subjective well-being

100 EvrppNcr-Bnse o THnonv<br />

(Wiese et aL.,2002). Moreover, participants with primarily work-oriented goals<br />

reported higher levels <strong>of</strong> general and work-related well-being than those who<br />

engaged in both work and family goals. These findings underscore the importance<br />

<strong>of</strong> selecting goals and setting priorities as adaptive regulatory mechanisms<br />

in personal goal involvement and development.<br />

Taken together, the summarized self-report studies support a positive association<br />

between the endorsement <strong>of</strong> SOC-related strategies and indicators <strong>of</strong> global<br />

and domain-specific well-being. Similar findings supporting the adaptive use <strong>of</strong><br />

SOC are reported by Lang, Rieckmann, and Baltes (2002; see also M. M. Baltes &<br />

Lang,7997). Thus, SOC seems to contribute to <strong>successful</strong> development and <strong>aging</strong><br />

throughout the adult years and into old and very old age.<br />

Taking a more process-oriented approach, a number <strong>of</strong> studies addressed the<br />

question <strong>of</strong> ruhst ospects <strong>of</strong> and horu selection, optimization, and compensation are<br />

related to positive functioning across life. A life span-developmental perspective<br />

ar5iues that the overall dynamic between optimization or approach goals (i.e.,<br />

goals directed at approaching positive outcomes) and compensation or avoidance<br />

goals (i.e., goals directed at preventing negative outcomes) should change with<br />

age. Civen the increase <strong>of</strong> losses and the decrease <strong>of</strong> gains over the life span, goals<br />

are hypothesized to shif t from a gain orientation (i.e., optimi zation, approach) in<br />

young adulthood to an orientation toward maintenance or loss avoidance (i.e.,<br />

compensation, avoidance) in later life (Ebner, 2005; Freund & Baltes, 2000; Freund<br />

& Ebner, 2005; Staudinger, Marsiske, & Baltes, 1995). If such an age-related shift<br />

in goal orientation is adaptive for man<strong>aging</strong> <strong>successful</strong>ly the changing balance <strong>of</strong><br />

gains and losses, younger adults should pr<strong>of</strong>it more from adopting goals that aim<br />

at optimizing their performance and older adults more from working on goals<br />

that are geared toward compensating losses in previously available means. Using<br />

a behavioral measure <strong>of</strong> persistence, namely, time, on a simple sensorimotor task<br />

that was framed in terms <strong>of</strong> either (a) optimizing performance or (b) compensating<br />

for losses, Freund (2006a) found evidence for age-differential motivational effects<br />

clf optimization versus compensation. Compared to younger adults, older<br />

adults were more persistent when pursuing the goal to compensate for a loss and<br />

Iess persistent when pursuing the goal to optimize their performance.<br />

In a similar vein, a series <strong>of</strong> studies by Ebner et al. (2006) propose that goals can<br />

be directed toward the improvement <strong>of</strong> functioning, toward the maintenance <strong>of</strong><br />

functional levels, and toward avoidance or regulation <strong>of</strong> loss. In a multimethod<br />

approach (self-report, preference-choice behavior), as well as different life contexts<br />

(cognitive and physical functioning), Ebner et al. found age-group differences<br />

in goai orientation and in the associations between goal orientation and<br />

subjective well-being. As expected and in line with the results by Freund (2006a),<br />

younger adults showed a primary goal orientation toward growth, whereas goal<br />

orientation toward maintenance and loss prevention became more important in<br />

old age. This age-related difference was shown to be related to perceived availability<br />

<strong>of</strong> resources. Moreover, loss prevention was negatively related to general<br />

well-being in younger but not older adults. Interestingly, in old age, orienting<br />

goals toward maintaining functions was positively associated with general subjective<br />

well-being. Together, the studies by Freund and Ebner et al. suggest that<br />

shifting one's goal orientation from the promotion <strong>of</strong> gains toward maintenance<br />

and loss prevention from early to late adulthood constitutes one mechanism <strong>of</strong><br />

adaptive goal selection.<br />

A study bY Ried<br />

goal relations as P<br />

adaptive aspects oI<br />

tion whether the rt<br />

in everyday life an<br />

was that older adu<br />

flict than younger<br />

competence to sele<br />

nonconflicting goi<br />

found that intergo<br />

well-being in ever<br />

ciated with highe<br />

goal attainment ol<br />

tiple goals into acc<br />

subjective well-be<br />

Several studies<br />

strategies on the I<br />

vided evidence fo<br />

outcomes in the c<br />

and Schmitz founr<br />

time studying the<br />

students low in se<br />

their exams.<br />

Several exPerin<br />

related differenct<br />

(Kemper, Hermar<br />

2001; Lindenbergt<br />

ferent from self-s<br />

allow individuals<br />

acterized by the<br />

menter) at the sa<br />

SOC in coordinat<br />

formance <strong>of</strong> mem<br />

performing both I<br />

primary domain I<br />

lected walking o<br />

Moreover, older<br />

handrail) to keel<br />

whereas younger<br />

thinking (i.e., slo<br />

bered). These agt<br />

over cognitive tas<br />

limits by increasi<br />

Taken together<br />

ioral level. Older<br />

ing) and comPe<br />

performance whr<br />

sources Primaril'<br />

to solving a men

Personalittl Theories o,f Successful Aging 101<br />

ily work-oriented goals<br />

t-being than those who<br />

underscore the importive<br />

regulatory mecharport<br />

a positive associatnd<br />

indicators <strong>of</strong> global<br />

ting the adaptive use <strong>of</strong><br />

see also M. M. Baltes &<br />

development and <strong>aging</strong><br />

I studies addressed the<br />

, and compensation are<br />

elopmental perspective<br />

:r approach goals (i.e.,<br />

pensation or avoidance<br />

rs) should change with<br />

cver the life span, goals<br />

mization, approach) in<br />

or loss avoidance (i.e.,<br />

& Baltes, 2000; Freund<br />

ch an age-related shif t<br />

he changing balance <strong>of</strong><br />

dopting goals that aim<br />

rom working on goals<br />

lvailable means. Using<br />

rple sensorimotor task<br />

lnce or (b) compensat-<br />

'ential motiva tiona I efyounger<br />

adults, older<br />

tpensate for a loss and<br />

lrformance.<br />

propose that goals can<br />

:d the maintenance <strong>of</strong><br />

)ss. In a multimethod<br />

as different life conrnd<br />

age-group differgoal<br />

orientation and<br />

Llts by Freund (2006a),<br />

growth, whereas goal<br />

ne more rmportant in<br />

:d to perceived availely<br />

related to general<br />

in old age, orienting<br />

:ed with general subrer<br />

et al. suggest that<br />

toward maintenance<br />

es one mechanism <strong>of</strong><br />

A study by Riediger, Freund, and Baltes (2005) addressed the nature <strong>of</strong> intergoal<br />

relations as possible characteristics differentiating between more and less<br />

adaptive aspects <strong>of</strong> goal selection. Specifically, Riediger et a1. examined the question<br />

whether the relationship among multiple personal goals affects goal pursuit<br />

in everyday life and subl'ective well-being. The first notable finding <strong>of</strong> their study<br />

was that older adults reported more facilitation between their goals and less conflict<br />