December 2012 - Putnam City Schools

December 2012 - Putnam City Schools

December 2012 - Putnam City Schools

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Curriculum<br />

re View<br />

Volume 5 Number 4<br />

<strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

Fern Melton<br />

CIA Director - Dr. Joe Pierce<br />

Dear PC Colleagues<br />

What does the Common Core-centered classroom look<br />

like? One approach worth developing is not all that new, but<br />

may be more relevant now than ever. Check these examples<br />

and the accompaning article recently featured in District<br />

Administrator magazine...<br />

“Project-based learning looks different, and may seem<br />

messier, than traditional instruction. Folks visiting PBL<br />

classrooms shouldn’t expect to see orderly rows of<br />

students moving through the curriculum together. Instead,<br />

they’re likely to find small teams of students working on<br />

investigations of open-ended questions. Students should be<br />

able to explain what they’re doing and how activities relate<br />

to the project goals.<br />

At Howe High School in the Howe Public <strong>Schools</strong> in<br />

Oklahoma, a small school making the shift to PBL, an<br />

administrator questioned a student about why he was in the<br />

hallway using his cell phone during class. Tammy Parks,<br />

district technology coordinator for Howe Public <strong>Schools</strong>,<br />

said the student had no trouble explaining his purpose: “He<br />

said, ‘I’m calling the mayor’s office to set up a meeting<br />

about our project.”<br />

Principal Rody Boonchouy of the Da Vinci Charter<br />

Academy in Davis, Calif., says that comprehensive evidence<br />

of learning in PBL should include “mastery of concepts,<br />

skills to achieve and demonstrate mastery, and detailed<br />

reflection of personal processes.” To encourage reflection,<br />

he recommends that administrators ask students “to talk<br />

about how they are learning,” including how their thinking<br />

has changed. He suggests using a reflection prompt that asks<br />

students to explain, “I used to think … but now I believe<br />

…”<br />

PBL typically culminates in public presentations of what<br />

students have learned, with audience members invited to ask<br />

questions, offer feedback, and score student performances.”<br />

The Challenge of Assessing Project-Based<br />

Learning<br />

On the heels of Common Core State Standards,<br />

administrators begin assessing critical thinking and content<br />

mastery.<br />

By:Suzie Boss, District Administration, October <strong>2012</strong><br />

Mesquite Elementary School students in the Vail (Ariz.) School<br />

District collaborate on a project as part of the school’s Media<br />

Center Enrichment Program. In anticipation of the new Common<br />

Core State Standards, the district is introducing projects at all<br />

grade levels to increase rigor and relevancy.<br />

Ask high school juniors at Da Vinci Charter Academy in the Davis<br />

(Calif.) Joint Unified School District, to explain the causes and<br />

consequences of war in American history, and you won’t get a rote<br />

recitation of dates and places.<br />

Instead, these students are able to demonstrate their learning by<br />

screening the preview for a feature film they produced on the<br />

conflict in Afghanistan through the eyes of a young American<br />

soldier. They can offer highlights of their interviews with Vietnam<br />

veterans, which they contributed to the Library of Congress as<br />

primary source material.<br />

For their ambitious project, called America at War, students didn’t<br />

just study history. They became historians. Their project offers<br />

compelling evidence of what students can accomplish through<br />

project-based learning (PBL), an instructional approach that<br />

emphasizes authentic assessment.<br />

The project earned top honors at last summer’s annual conference<br />

of the New Technology Network, a group of 120 all-PBL public<br />

high schools, including charters and magnet schools in 19 states.<br />

For Rody Boonchouy, principal of Da Vinci Charter Academy,<br />

the project was worth doing because of the deep learning it<br />

produced. “Students had a transformational learning experience<br />

by diving deep into all the dynamic implications of war,” he says.<br />

“Their preexisting beliefs and opinions were challenged through<br />

exploration of conflicts and interactions with veterans who were<br />

there.”<br />

(continued on pg. 2)

PBL as Driver of Change<br />

A third-grade class in Robious Elementary School in the<br />

Chesterfield County (Va.) Public <strong>Schools</strong> planted seeds and<br />

sprouts in the school community garden as a lesson in the plant<br />

unit.<br />

Although PBL has a long history in American education, dating<br />

to John Dewey and other early advocates of learning by doing,<br />

the project approach has gotten a second wind over the past<br />

decade as a strategy to engage diverse learners in rigorous<br />

learning.<br />

Early adopters include several public school networks, such as<br />

the New Tech schools, that leverage technology-infused PBL as a<br />

driver of school change. High Tech High, which has a deliberate<br />

focus on preparing high-poverty students for college, began<br />

with one school in Southern California and has expanded to 11<br />

public charter schools, elementary through high school, across<br />

San Diego County. Expeditionary Learning, another national<br />

network, reaches approximately 50,000 students in a variety<br />

of K12 public school settings. Its model emphasizes servicelearning<br />

and place-based projects that have strong connections to<br />

communities.<br />

PBL is expanding beyond these early adopters as districts<br />

consider strategies to help students meet the Common Core<br />

State Standards. In projects such as America at War, students<br />

are assessed based on what they produce or demonstrate rather<br />

than what they can recall for a test. “That application of learning<br />

is a higher need as we transition to the Common Core,” says<br />

Superintendent Calvin Baker of the Vail School District in<br />

Arizona. In anticipation of the new standards, his district is<br />

introducing projects at all grade levels, with the dual goals of<br />

increasing “rigor and relevancy.”<br />

Robious Middle School students in the Chesterfield County<br />

schools work with volunteers from the nearby James River Park<br />

system to learn about geocaching. During this activity, students<br />

incorporate multiple skills, like map reading and learning<br />

concepts of interconnectedness to the watershed.<br />

And Holly Bremerkamp, Acuity product manager at CTB/<br />

McGraw-Hill, adds that project-based learning and assessments<br />

are becoming increasingly important as there is a need to<br />

measure students’ abilities to think critically and collaborate with<br />

peers. Acuity is a comprehensive assessment-as-learning support<br />

system. “We’ve found that project-based learning methods—and<br />

the performance-based assessments that accompany them—<br />

are valuable in pushing students to demonstrate what they<br />

have learned in meaningful ways and valuable for teachers<br />

to understand how well students can apply their knowledge,”<br />

Bremerkamp says.<br />

Beyond the Bubble<br />

For administrators accustomed to the bubble tests of No Child<br />

Left Behind, the decision to implement PBL across a school<br />

system raises a challenging question: How should districts<br />

assess more open-ended learning that likely involves critical<br />

thinking and collaboration as well as content mastery? Rather<br />

than testing for recall of information, projects are better suited to<br />

performance-based assessments that ask students to demonstrate,<br />

apply and reflect on what they have learned.<br />

At Federal Hocking High School, part of Federal Hocking Local<br />

<strong>Schools</strong> in Stewart, Ohio, students end each semester with halfday<br />

performances of learning. Physical education students might<br />

be asked to design a personalized, hour-long exercise program,<br />

based on analysis of their own metabolic data, to work off the<br />

calories in a candy bar.<br />

“Students should be able to demonstrate their knowledge<br />

through application. That’s the ticket,” says George Wood, who<br />

is both superintendent of Federal Hocking Local <strong>Schools</strong> and<br />

principal of Federal Hocking High. He is also board president<br />

for the Coalition of Essential <strong>Schools</strong>, a nonprofit that promotes<br />

personalized learning and intellectual excellence in hundreds of<br />

member schools nationwide.<br />

Performance assessments like the ones Federal Hocking uses are<br />

still relatively rare in public schools, but they could soon become<br />

more commonplace. Two organizations have won federal<br />

contracts to develop next-generation assessment systems for<br />

English language arts and math. The Partnership for Assessment<br />

of Readiness for College and Career (PARCC) and the Smarter<br />

Balanced Assessment Consortium are developing measurement<br />

tools, with implementation expected by the 2014-2015 school<br />

year.<br />

Students at Da Vinci Charter Academy take part in a WWI<br />

project whereby each student team represents one nation in the<br />

war with role playing.<br />

Many observers are predicting parallels between the new<br />

assessments and the authentic assessment called for in PBL.<br />

PARCC describes its forthcoming assessments, for grades 3<br />

through high school, as “rich performance tasks” that will<br />

measure students’ readiness for entry-level college courses.<br />

Smarter Balanced recently released a sample of a pilot<br />

assessment task that asks students in grade 11 to “engage<br />

strategically in collaborative and independent inquiry to<br />

investigate/research topics, pose questions, and gather and<br />

present information.” That description prompted David Ross,<br />

director of teacher professional development for the Buck<br />

Institute for Education (BIE), a nonprofit resource for projectbased<br />

learning, to remark in a blog post, “Sounds like PBL to<br />

me.”<br />

Foot in Both Worlds<br />

Until the new assessments are rolled out, districts remain<br />

accountable to traditional state assessments, even if they’re<br />

shifting their instructional model to PBL. “We’re trying to stand<br />

with a foot in both worlds,” Baker says. “Everyone’s talking<br />

about what the new assessments will be like, but no one has<br />

shown them to us yet. When assessment changes, it’s a whole<br />

new game.” “We know that students can do more than what’s<br />

assessed by current state tests,” adds Allison Rowland, a former<br />

principal in California who is now an assessment specialist for<br />

New Tech Network.<br />

She welcomes the new generation of assessments, calling them<br />

“a means to drive students toward deeper learning and stronger<br />

preparation for college.” As administrators, she says, “we pay<br />

attention to what we measure. If we can shift the measurement<br />

so that students are better prepared and more engaged learners,<br />

then let’s do it.”<br />

Overcoming Anxiety<br />

Not all administrators are so eager for the changes ahead.<br />

“Leaders at the district and state levels are feeling some anxiety<br />

about moving to an assessment system that’s more open-ended,”<br />

acknowledges Rosanna Mucetti. A former principal, Mucetti is<br />

the director of district and state initiatives for BIE, which has<br />

been promoting best practices in PBL for 25 years.<br />

Under No Child Left Behind, districts across the country

have kept a laserlike focus on standardized test results.<br />

“Administrators have spent a decade getting up in front of their<br />

organizations, emphasizing data and meeting targets,” Mucetti<br />

says. “We’ve all been conditioned to pay close attention to that.<br />

The future horizon is not as crystal clear in terms of assessment.<br />

People are wondering, ‘What’s coming? And in the interim, what<br />

evidence should we focus on?’ There’s this tension.”<br />

Answers with One Model<br />

Students in the New Tech @ Ruston school, part of the New<br />

Technology Network, in the Lincoln Parish School Board in<br />

Louisiana take part in a Recyclable Roller Coasters project. They<br />

created a roller coaster from recyclable materials that could roll<br />

a marble unassisted for 20 seconds. In doing so, they learned<br />

about potential energy, kinetic energy, work and the law of<br />

conservation of energy.<br />

Answers are emerging from both practice and research. On the<br />

practice side, BIE emphasizes effective assessment strategies<br />

during its popular three-day professional development workshop,<br />

PBL 101, which it offers to teachers and instructional leaders in<br />

participating districts across the country. During the workshop,<br />

teachers develop rubrics to assess students’ final projects<br />

according to multiple measures. Students are assessed on mastery<br />

of significant academic content plus development of specific<br />

21st-century skills, such as collaboration or critical thinking.<br />

The BIE model also emphasizes using formative assessment<br />

strategies throughout a project to check on student understanding<br />

and to make just-in-time adjustments in instruction. (Samples<br />

of summative and formative tools are available at www.bie.org/<br />

tools/freebies.)<br />

On the research side, evidence of the value of PBL for rigorous<br />

coursework is emerging from an ongoing multiyear study called<br />

Knowledge in Action, designed by University of Washington<br />

researchers and implemented by Advanced Placement teachers<br />

in three states. Funded by an alliance that includes the George<br />

Lucas Educational Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates<br />

Foundation, the study shows that AP pass rates increased by<br />

as much as 30 percent during the 2011-<strong>2012</strong> school year when<br />

students engaged in a project-based curriculum rather than more<br />

traditional instruction. Researchers emphasize that projects need<br />

to be the “spine” of the curriculum rather than add-ons. (Read<br />

more at education.washington.edu/research/rtm_11/knowledgein-action.html.)<br />

Rethinking Assessments<br />

To paint a clearer picture of assessment in PBL, 20 teachers<br />

(still being selected as of early August) from New Tech schools<br />

in several states are starting a yearlong research project on<br />

performance assessment. Funded by the Hewlett Foundation’s<br />

Deeper Learning initiative, the national study will take place<br />

throughout the <strong>2012</strong>-2013 school year, with results expected by<br />

next summer. “We’re piloting performance assessments that are<br />

aligned to the Common Core and that will demonstrate students’<br />

readiness for college,” says New Tech Network’s Rowland.<br />

PBL emphasizes student choice and open-ended questions.<br />

“There’s an infinite number of projects you could do,” Rowland<br />

points out. “We want to make sure that PBL adds up to students<br />

actually being ready for college.”<br />

The Stanford University Center for Assessment, Learning<br />

and Equity researchers are consulting on the Deeper Learning<br />

research to determine which competencies to assess to ensure<br />

that high school graduates are indeed college-ready. Rowland<br />

says that assessments will be systematic and common across<br />

schools. Teachers at different schools might select different<br />

novels for language arts projects, for example, “but the rubrics<br />

and expectations of students will be the same.” Teachers will<br />

spend time examining student writing, video productions, and<br />

other project artifacts together as part of the yearlong study. That<br />

practice is already common in many PBL schools. High Tech<br />

High teachers, for example, use a protocol for examining student<br />

work together. “We do it to have a narrative of quality work,”<br />

High Tech High founder Larry Rosenstock explained during a<br />

recent conference presentation.<br />

Considering the Deeper Learning research project, a Webbased<br />

platform is being developed that will allow teachers from<br />

different states to upload student work samples. That means<br />

teachers at different locations “can assess student work together<br />

and calibrate around it,” Rowland says. “We’ll be looking not<br />

just within a school but across schools in our network.” The<br />

result, she continues, should be a sharper picture “of what it<br />

means to have high-quality, proficient student work.”<br />

Insights from these PBL early adopters “could create proof<br />

points of success” for the hundreds more school systems that are<br />

just starting to shift to projects, says BIE’s Mucetti. “They need<br />

to see how this would be replicable to their system.”<br />

Bold Leadership<br />

One district to watch is Chesterfield County (Va.) Public<br />

<strong>Schools</strong>, which serves 60,000 students. To update its strategic<br />

plan, the district spent the last two years conducting a series of<br />

community forums that engaged parents, students, teachers and<br />

business leaders, and that included guests such as an astronaut,<br />

an entrepreneur, a peace activist and a futurist. “They helped<br />

us paint a vision of what our students need for the future,” says<br />

Donna Dalton, the district’s chief academic officer.<br />

Chesterfield County’s strategic planning process pointed to PBL<br />

as the way to realize that vision, and now the district is preparing<br />

to introduce PBL across the entire system. It will start with<br />

six “trailblazer” schools that will become demonstration sites<br />

for PBL. The first wave of professional development will be<br />

provided by BIE next summer. The district plans to grow its own<br />

teacher-leaders for professional development by 2015 when PBL<br />

will reach all 62 schools. As the initiative expands, teachers will<br />

be involved in developing common rubrics and other assessment<br />

tools.<br />

Costs and Timeline<br />

The costs of shifting to project-based instruction and assessment<br />

are hard to quantify, but they primarily involve time and<br />

resources for professional development. “This requires a shift<br />

in focus in teaching,” says Rowland. “That involves teacher<br />

learning, which takes time.” If teachers are new to performance<br />

assessment, they may need to learn how to write rubrics and help<br />

students understand what high-quality project work looks like.<br />

To ensure that similar standards are applied from one classroom<br />

to the next, teachers also need time to examine student work<br />

together. “If you’re measuring something that’s not a bubble-in<br />

answer, it takes more conversation and calibration,” Rowland<br />

explains.<br />

Research presented at the American Educational Research<br />

Association’s annual meeting in April <strong>2012</strong> underscores the need<br />

for professional development to help teachers gain confidence<br />

with PBL methods. Using Project Based Learning to Teach<br />

21st-Century Skills: Findings from a Statewide Initiative<br />

reported results from a pioneering West Virginia initiative<br />

in which teachers became peer leaders in a statewide PBL<br />

Curriculum reView <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

3

ollout. The study found that teachers who engaged in extended<br />

professional development have been able to implement projects<br />

“as a way to teach and assess 21st-century skills without<br />

sacrificing academic rigor.”<br />

In the Vail School District, common grade-level projects are<br />

being developed by lead teachers from all 17 schools. “Having<br />

common projects gives teachers a model of expectations [for<br />

quality work] and templates for project design they can use<br />

in their classroom,” explains Deborah Hedgepeth, assistant<br />

superintendent for instruction.<br />

Rather than bringing in outside experts, the Vail district is<br />

growing its own capacity to do PBL. The 20-plus teachers<br />

developing grade-level projects “are the experts who can work<br />

with their fellow teachers,” Hedgepeth says. She estimates<br />

that the cost of bringing her teachers together to spend four<br />

days intensively poring over the curriculum is about $60,000.<br />

“But that’s just a small piece of it,” she explains, adding that<br />

follow-up work at the local school level makes it difficult to put<br />

a price tag on the whole effort.<br />

For smaller districts, the challenge of developing new assessment<br />

systems can be traumatic, says Vail’s Baker, especially in tight<br />

budget times. His district digitizes its curricula and assessment<br />

materials and shares them for a fee on an award-winning site<br />

called Beyond Textbooks (beyondtextbooks.org). The site is used<br />

by 70 districts and individual charter schools across Arizona.<br />

“Our goal isn’t to make a profit, Baker says. “It’s to help other<br />

districts improve the academic achievement of their students and<br />

be ready for the sweeping changes ahead.”<br />

Suzie Boss is the author of Bringing Innovation to School and<br />

Reinventing Project-Based Learning. She is a member of the<br />

Buck Institute for Education’s national faculty.<br />

Secondary Language Arts - Ranee Staats<br />

Adolescent Literacy, Part 1: School-Wide<br />

Literacy Planning<br />

Posted on October 30, <strong>2012</strong> by Ed View 360, By Joan<br />

Sedita<br />

PART 1<br />

In recent years there has been a growing interest in<br />

adolescent literacy, especially as Americans become<br />

more concerned about the economic and civic health of<br />

the nation. Literacy skills are necessary more than ever<br />

to succeed in college and work, as well as to manage the<br />

everyday life demands of an increasingly more complex<br />

society and world economy. The best example of this focus<br />

is the tagline “college and career ready” from the Common<br />

Core State Standards (CCSS).<br />

More middle and high school leaders are beginning<br />

to acknowledge that they must develop a school-wide<br />

approach to teaching literacy skills that includes two tiers<br />

of instruction. The first tier is content literacy instruction<br />

for all students that is delivered in regular classes,<br />

including history, science, math, and English/language arts.<br />

The second tier is literacy instruction for struggling readers<br />

that is delivered partly in regular content classes and<br />

partly in intervention settings (including extended English/<br />

language arts blocks and individual/small-group settings).<br />

A school-wide approach to literacy instruction must<br />

involve all teachers in the delivery of reading and writing<br />

instruction, including content-area teachers and staff who<br />

work with special populations. This is a major tenet of the<br />

literacy CCSS. A successful school-wide plan must also<br />

have strong, committed leadership that provides ongoing<br />

support for literacy instruction.<br />

A Literacy Planning Model<br />

I have worked with numerous schools and districts to<br />

help develop literacy plans using a planning model that<br />

addresses six components:<br />

1. Establishment of a literacy planning team<br />

2. Assessment planning for screening, guiding instruction,<br />

and progress monitoring<br />

3. Literacy instruction in the content classroom<br />

4. Interventions for struggling readers that address phonics,<br />

word study, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension skills<br />

5. Flexible scheduling to allow for grouping based on<br />

instructional needs<br />

6. Professional development planning<br />

A key first step is to assemble a literacy planning team<br />

that is representative of the major stakeholders who will<br />

have to implement the plan. Members of the team should<br />

include teachers of all subject areas, interventionists,<br />

parents, reading specialists, and administrators. It is<br />

important to recognize that literacy planning is a process,<br />

not an event. Like most school-wide initiatives, developing<br />

and executing a literacy plan will take time and sustained<br />

effort; literacy planning teams should be prepared for the<br />

process to take 1–3 years.<br />

Once a planning team is assembled, the first step is to<br />

take stock of what is already in place in relation to the<br />

six components. This includes gathering information that<br />

answers questions such as:<br />

What assessments are currently used to identify good and<br />

struggling readers?<br />

What assessments are used to identify specific needs of<br />

individual struggling readers? What reading instruction<br />

is already taking place in content classrooms, and what<br />

professional development do content teachers and<br />

others need in order to effectively address all reading<br />

components?<br />

What reading interventions and supplemental reading<br />

programs are currently offered for struggling readers?<br />

What information and professional development do the<br />

teachers of struggling readers need?<br />

Is the scheduling process flexible enough to accommodate<br />

different grouping patterns for struggling readers?<br />

After information has been collected to answer these<br />

questions, the planning team can set and prioritize goals<br />

and action steps for each of the six components. Some<br />

action steps are like low-hanging fruit—easy to accomplish<br />

quickly and with minimal expense. Other action steps will<br />

take longer to address. A concrete plan for addressing the<br />

Curriculum reView <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

4

action steps throughout the coming year or two is essential<br />

to keep the process moving forward.<br />

A literacy assessment plan is key to successfully<br />

implementing a school-wide literacy plan. Screening<br />

literacy assessments provide the data to determine which<br />

students are struggling, while diagnostic assessments help<br />

determine why they struggle, and progress monitoring<br />

assessments determine if instruction is working in both<br />

content classrooms (Tier I) and with supplemental<br />

instruction (Tier II)<br />

The six planning components are interrelated. Action steps<br />

for one component need to be related to action steps for the<br />

other components. For example, decisions about both tiers<br />

of instruction should be based on assessment data, along<br />

with how to group students and schedule supplemental<br />

instruction. Plans for professional development should be<br />

made based on the needs of teachers and other members of<br />

the team.<br />

Middle and high school administrators must make<br />

the acquisition of literacy skills a priority and provide<br />

adequate time in the school schedule for reading and<br />

writing instruction. They must also be willing to use<br />

flexible grouping patterns when scheduling students in<br />

order to implement a two-tiered model for delivering<br />

reading instruction in both content classes and intervention<br />

settings. Professional development for content teachers and<br />

specialists is also essential.<br />

The time, effort, and expertise necessary to develop<br />

a school-wide plan for providing effective literacy<br />

instruction to all students present a challenge for most<br />

middle and high schools. The challenge is worth taking, as<br />

there is an urgent need to improve the reading, writing, and<br />

comprehension skills of these students.<br />

Elementary Language Arts - Melissa Ahlgrim<br />

Daily 5 and Writing<br />

We had a great turnout at the recent trainings for small<br />

group instruction. As you will recall, we spent quite a bit<br />

of this time talking about how to structure the classroom<br />

so that students are independently engaged in rigorous<br />

work while the teacher is working with a small group. One<br />

possible structure that was introduced was Daily 5.<br />

The Daily 5 is a structure for organizing literacy<br />

instruction. It is designed as a “catch and release” model—<br />

where the teacher catches the students in for short, targeted<br />

instruction as a whole group, then releases them back to<br />

practice the skills learned independently. When students<br />

are released to work, they are working through rotations<br />

like Read to Self, Read to Someone, Listen to Reading,<br />

Work on Writing, and Word Work. This cycle can be<br />

repeated as many times as needed, ending with some short<br />

closure at the end to discuss what we learned and how<br />

things went that day.<br />

One of the most essential components of Daily 5 is<br />

the explicit instruction of procedures. In both the workshop<br />

we offered and in the book, time was spent talking<br />

about how these procedures are introduced. The teacher<br />

introduces the activity (such as Read to Self) to students,<br />

discussing the PURPOSE of the activity. The students then<br />

help the teacher create an I-CHART (I=Independent) to<br />

list the procedures or expectations for the students. This is<br />

one step I am finding that we are often skipping, but it is<br />

a critical piece. Students (and teachers) need to have these<br />

procedures and expectations in writing, where they can<br />

be referred to often. When evaluating how the activity is<br />

going, students (and teachers) need to be able to look at<br />

these expectations to identify what is going well and what<br />

needs to be fixed. Teachers need to be able to point out<br />

specific actions to praise or correct so that students can<br />

understand the feedback being given.<br />

After identifying the purpose and creating an<br />

I-Chart, students need to be able to practice often. Having<br />

students model what the activity should, as well as should<br />

NOT, look like helps students understand exactly what<br />

is being expected of them. As they go off to practice, the<br />

need to be able to practice correctly to build their stamina.<br />

The phrase “practice makes perfect” is erroneous. It should<br />

be “perfect practice makes perfect”. Once students are<br />

practicing, as teachers we need to get out of the way for<br />

two reasons: (1) we don’t want to interrupt their work and<br />

(2) we don’t want them to be dependent on us to monitor<br />

their behavior. When we talk about getting out of the<br />

way, we are not saying to go grade papers, check e-mail,<br />

etc. This is the time to be hyper-alert to what students are<br />

doing without them being aware of what you are doing.<br />

This can be hard!<br />

So how long should we spend building this<br />

stamina? The general rule of thumb is that once K-1<br />

students have achieved 7-8 minutes, 2-3 students are at<br />

9-10 minutes, and 4-5 students are at 11-12 minutes, you<br />

are ready to introduce a new activity and keep things<br />

moving.<br />

Once procedures and structure are in place, don’t<br />

forget about content! The Daily 5 allows for how to<br />

structure our students, but what you teach is not specified.<br />

This is where our resources, such as Rigby, come in. When<br />

thinking about how our students are getting a balance of<br />

grade level content with working on their own level, think<br />

of it this way: during the whole group mini-lesson you<br />

are exposing students to grade level text and content. The<br />

small group time and centers are your opportunity to have<br />

students work at their instructional level on the content<br />

they need—whether it is reinforcing the content taught<br />

in the whole group, remediating foundational skills the<br />

student is lacking, or having them move beyond the grade<br />

level expectations.<br />

Curriculum reView <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

5

Elementary Math - Paula Dyer<br />

Fluency<br />

The required fluency in the Common Core standards are:<br />

Kindergarten – Add/subtract within 5<br />

1st – Add/subtract within 10<br />

2nd – Add/subtract within 20 and Add/subtract within 100<br />

3rd – Multiply/Divide within 100 and Add/subtract within<br />

1000<br />

4th – Add/subtract within 1,000,000<br />

5th – multiply multi-digit whole numbers<br />

As we are using Common Core standards the fluencies<br />

look different as we progress through the grade levels.<br />

Fluency is defined as accuracy (correct answer), efficiency<br />

(a reasonable amount of steps), and flexibility (using<br />

strategies).<br />

Fluency is more than just a timed test where students<br />

are just rote memorizing numbers. It is more about how<br />

numbers work together.<br />

In Kindergarten fluency is an understanding and<br />

internalizing the relationships that exist between and<br />

among numbers. Seeing facts related to other facts (fact<br />

families), understanding what the commutative property is,<br />

seeing sub-parts within a number.<br />

With repeated experiences with many different types of<br />

concrete materials Kindergarten students will recognize<br />

that there are only particular sub-parts for each number.<br />

A Kindergarten teacher shared that she was doing another<br />

number talk with the number 5. She showed the students<br />

5 items, then took 2 away and asked the class how many<br />

were in the other hand. They had done this activity with 5<br />

items multiple times, sometimes taking 1 away, 2 away, 3<br />

away or none away, over and over. But on this particular<br />

day as some of the students responded you have 3 one of<br />

her students said, “Oh, I get it, 2 and 3 and 3 and 2 always<br />

makes 5.” This is fluency, understanding and internalizing<br />

that there are only particular sub-parts for each number.<br />

We must be diligent working on Number Sense, attaching<br />

number to quantity, recognizing numerals, writing<br />

numerals, seeing all the parts for each number, relating<br />

addition with subtraction (not making these separate<br />

entities). As we progress through elementary our students<br />

need to dig deep into the meanings of numbers and how<br />

they work, they need to find strategies that they can use so<br />

that they understand the meaning behind.<br />

Let your students struggle with problems and share with<br />

their peers how they solve the problem. Learning is more<br />

than listening.<br />

ELL- Dr. Jean Laine’<br />

This month’s article answers the following frequently<br />

asked questions:<br />

Is there a significant difference between the pull-out<br />

and push-in or pull-in ESL program models? How much<br />

time per week should ELL students spend in the ESL<br />

classroom?<br />

The pull-out English as a Second Language (ESL) program<br />

model is by far the most popular ESL instructional model<br />

in the world because it is easier to implement than the<br />

push-in one, especially, when resources are scarce. For<br />

instance, a school with a high number of ELL students<br />

may not be able to adequately meet the instructional needs<br />

of all the ELL students in the mainstream classroom with<br />

the push-in model. <strong>Schools</strong> would do better to pull out the<br />

students during specials so that ESL teachers can address<br />

language development in a meaningful way. Serving<br />

all ELL students is a must, and it is a federal mandate.<br />

Therefore, school districts do not have the luxury of<br />

picking and choosing which students to serve. All the<br />

students who are identified as limited English proficient<br />

should receive ESL instruction. School districts are<br />

required to monitor proficient students for two years to<br />

ensure that they are able to show real academic progress in<br />

mainstream classrooms.<br />

The ESL pull-out program model has been used in both<br />

elementary and secondary schools in the form of small<br />

flex groups or a class period. At the elementary level, it is<br />

recommended that English language learners (ELLs) spend<br />

30 minutes daily in the ESL classroom. When resources<br />

are scarce, school districts may opt for 30 minutes three<br />

to four days a week, but experts in linguistics suggest a<br />

daily meeting time in order to guarantee higher probably of<br />

academic success.<br />

As far as the pull-in or push-in model is concerned, it is<br />

used mainly at the elementary school settings. The ESL<br />

teacher goes into the regular classrooms to teach the ELL<br />

students. The content of the instruction is based on the<br />

objectives selected by the regular classroom teacher(s).<br />

The nature of this ESL instructional model is contentbased.<br />

This instructional model should be used when the<br />

ESL teacher involved is certified in elementary education,<br />

and he or she feels comfortable working collaboratively<br />

with the mainstream classroom teacher.<br />

Having examined ELL students’ performance data for<br />

six years in the <strong>Putnam</strong> <strong>City</strong> school district, I have not<br />

seen any significant difference between the pull-out and<br />

push-in models. Both models seem to work when they are<br />

implemented with fidelity. Principals should endeavor to<br />

support ESL teachers by ensuring that they have access<br />

to all the ELL students daily. The push-in model should<br />

be avoided if it means serving just a few of the total ELL<br />

students at the respective site.<br />

This is a good time in education.<br />

Curriculum reView <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

6

The Arts - Jason Memoli<br />

A Commitment To Music In Education<br />

“We must move beyond art for art’s sake, to convey the<br />

importance of art for education’s sake.”<br />

—Dr. Charles fowler, strong arts, strong schools, 1996<br />

With the Journal for Learning Through Music, the New<br />

England Conservatory, through its Music Education<br />

department and Research Center for Learning Through<br />

Music, supports the belief that this is a critical time<br />

for music and the arts in schools. This new journal is<br />

intended to promote a national discourse focused on the<br />

extraordinary range of learning associated with music by<br />

providing a forum for the discussion of new perspectives<br />

on the essential role music can play in public school<br />

education. By providing a vehicle for joining evidence of<br />

the impact of 1) musical training on learning, 2) successful<br />

arts in education programs, and 3) positive change in<br />

schools due to music, the thinking and practices can be<br />

strengthened everywhere.<br />

The Journal is intended to speak to a broad audience:<br />

artists, teachers, educators, researchers, policy makers, and<br />

leaders of both cultural and arts-in-education organizations.<br />

It is hoped that members of that varied audience will<br />

find in this publication a place to describe efforts, share<br />

questions and findings, and engage in the debates that are<br />

necessary if the role of music in classrooms is to be more<br />

fully articulated and realized.<br />

In order to present some of the many perspectives on<br />

Learning Through Music, the Journal includes articles<br />

that, taken together, focus on the philosophy, research,<br />

and innovative program practices that address issues<br />

concerning the essential role of music in education reform.<br />

We want here to recognize the report, Champions of<br />

change: The impact of the arts on learning<br />

(Edward Fiske, 1999). It serves as a primary point of<br />

departure for the ongoing discourse about the role of music<br />

in the context of the arts education and school change<br />

efforts represented in this journal.<br />

The Journal also features interleaved “conversational<br />

interludes,” “photo essays,” and “provocative examples<br />

from the field,” meant to stimulate interconnections among<br />

the multiple perspectives from article to article. These<br />

“connectives” are intended to stimulate commentary<br />

that supports discourse between the authors and reports<br />

from the field. Accordingly, examples, imagery, and<br />

commentary emanating from ongoing action research at<br />

school sites are intended both to intro- duce each paper<br />

and to further the conversations implicit across articles.<br />

The first two issues of the Journal for Learning Through<br />

Music are intended to provide a focal point for the debate<br />

concerning the most appropriate and effective role of<br />

music as a resource and tool for arts efforts in public<br />

schools.<br />

THE FIRST ISSUE: AUGUST 2000<br />

This first issue is devoted largely to topics presented at<br />

the conference, “Why Integrate Music Throughout the<br />

Elementary School Curriculum?” hosted a year ago in<br />

Ipswich Massachusetts by the New England Conservatory.<br />

It explores various perspectives on this topic by including:<br />

• Commentary from philosophical and historical<br />

perspectives on music in the context of arts in education<br />

• Interviews, essays, and action research reports that reveal<br />

the practical experience of developing New England<br />

Conservatory’s new Learning Through Music Partnership<br />

<strong>Schools</strong><br />

• Research underway at the New England Conservatory<br />

that considers music and learning from qualitative and<br />

quantitative perspectives.<br />

THE SECOND ISSUE: WINTER, 2001<br />

A second issue, “Making Music Work for Public<br />

Education: Innovative Program Development and Research<br />

from a National Perspective,” is to be published in the<br />

winter of 2001. It will present findings from New England<br />

Conservatory’s national conference held on September 7-<br />

9, 2000. This issue will feature a broader range of topics,<br />

including keynote presentations, panel discussions, and<br />

roundtable responses which focus on the implications of<br />

music in education programs from a national perspective.<br />

We anticipate that the Journal for Learning Through<br />

Music will soon be available in electronic form. This<br />

format will allow authors to make better use of photographic<br />

evidence and documentation. It will also allow the<br />

presentation of video documentation of lessons, programs,<br />

interviews, and performances. <br />

REFERENCES<br />

Fiske, Edward B. (Ed.). (1999). Champions of change: The<br />

impact of the arts on learning. Arts Education Partnership<br />

and the President’s Committee on the Arts and the<br />

Humanities.<br />

Fowler, Charles. (1996). Strong arts, Strong <strong>Schools</strong>: The<br />

Promising Potential and Shortsighted Disregard of the<br />

Arts in American Schooling. New York: Oxford University<br />

Press.<br />

Curriculum reView <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

7

Social Studies - Brenda Chapman<br />

NCHE’s History’s Habits of the Mind<br />

(Guidelines for Teaching History in <strong>Schools</strong>, Bradley Commission and NCHE)<br />

Courses in history, geography, and government should be designed to take students well beyond formal skills of critical<br />

thinking, to help them through their own active learning to:<br />

• Understand the significance of the past to their own lives, both private and public, and to their society.<br />

• Distinguish between the important and the inconsequential, to develop the “discriminating memory” needed for a<br />

discerning judgment in public and personal life.<br />

• Perceive past events and issues as people experienced them at the time, to develop historical empathy as opposed<br />

to present-mindedness.<br />

• Acquire at the same time a comprehension of diverse cultures and shared humanity.<br />

• Understand how things happen and how things change, how human intentions matter, but also how their<br />

consequences are shaped by the means of carrying them out, in a tangle of purpose and process.<br />

• Comprehend the interplay of change and continuity, and avoid assuming that either is somehow more natural, or<br />

more to be expected, than the other.<br />

• Prepare to live with uncertainties and exasperating, even perilous, unfinished business, realizing that not all<br />

problems have solutions.<br />

• Grasp the complexity of historical causation, respect particularity, and avoid excessively abstract generalizations.<br />

• Appreciate the often tentative nature of judgments about the past, and thereby avoid the temptation to seize upon<br />

particular “lessons” of history as a cure for present ills.<br />

• Recognize the importance of individuals who have made a difference in history, and the significance of personal<br />

character for both good and ill.<br />

• Appreciate the force of the non-rational, the irrational, and the accidental, in history and human affairs.<br />

• Understand the relationship between geography and history as a matrix of time and place, and as a context for<br />

events.<br />

• Read widely and critically in order to recognize the difference between fact and conjecture, between evidence<br />

Rubber and Glue by www.xkcd.com<br />

and assertion, and thereby frame useful questions<br />

Curriculum reView <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

8

Science-Bob Melton<br />

Lesson learned! Next Generation Science<br />

Standards<br />

by Doug Haller, November 27th, <strong>2012</strong> http://smartblogs.com/<br />

education/<strong>2012</strong>/11/27/lesson-learned-next-generation-standardsbuild-challenges-encountered-1990s-douglas-f-haller-ed-m/<br />

The second public draft of the Next Generation Science<br />

Standards, developed by Achieve, is due for release before<br />

the new year. This draft represents step four in a ninestep<br />

process to update standards for K-12 sciences and<br />

engineering education. The nine-step process includes three<br />

public and two state review and comment periods before<br />

delivery of a final product. Once complete, states will opt<br />

to select or not select the NGSS for local implementation.<br />

The NGSS focus on science and engineering education<br />

whereas the Common Core State Standards initiative<br />

addresses math and English language arts education<br />

standards. The two independent efforts seek to achieve<br />

very similar goals: preparing U.S. students for academic<br />

and career success and global competitiveness in the 21st<br />

century. Each effort also seeks to provide educators and<br />

parents clear, cohesive and consistent guidelines that lead<br />

to a robust and meaningful education.<br />

The common core and NGSS initiatives benefited greatly<br />

from hard lessons learned during the development and<br />

implementation of the first generation of education<br />

standards disseminated in the 1990s. First and perhaps<br />

foremost, the current efforts actively sought state<br />

participation at the start of the process. National standards<br />

developed in the 1990s came across as top-down mandates.<br />

Next, the latest standards appear very concise and<br />

cohesive. In my area of expertise, science, the first draft<br />

NGSS were only 90 pages in length whereas the original<br />

NRC Standards and AAAS Benchmarks exceeded 200<br />

and 400 pages respectively. Thirdly, NGSS developers<br />

have anticipated the relationship between standards and<br />

assessment. The first generation of education standards<br />

led to a cycle of assessment development and standardized<br />

testing. The NGSS start with performance expectations<br />

that are aligned to scientific and engineering practices,<br />

crosscutting concepts, and disciplinary core ideas. Starting<br />

with how and what to assess, rather than what to teach,<br />

focuses on learning rather than teaching, placing the<br />

student at the center of the process.<br />

The Council of Chief State School Officers and the<br />

National Governors Association initiated the common core<br />

effort. These groups elected to focus on math and ELA.<br />

The “3 Rs” continue to heavily influence early elementary<br />

education — without a strong foundation in reading,<br />

writing and mathematics students struggle throughout<br />

grades K-12 regardless of the subject matter. The NGSS<br />

derive from a 400-plus page document known as the<br />

“Frameworks” developed by a team of scientists, engineers<br />

and experts in science and engineering education from<br />

the National Research Council. The Frameworks could be<br />

likened in the new standards process to the NRC Standards<br />

and AAAS Benchmarks of the 1990s. However, this time<br />

the Frameworks were written to inform the development of<br />

the NGSS rather than to act as the standards.<br />

“48 states and territories, the District of Columbia, and the<br />

Department of Defense Education Activity have adopted<br />

the Common Core State Standards and are in the process<br />

of implementing the standards locally.” — Council of<br />

Chief State School Officers.<br />

Let’s hope that the NGSS receive as much support as the<br />

common core standards. The NGSS effort includes 26<br />

states that likely will adopt the final product. The original<br />

science education standards were rarely adopted directly<br />

by states. Rather, states reviewed the Standards and<br />

Benchmarks, reinterpreting them into actionable items for<br />

teachers, a costly and time-consuming effort.<br />

Of course, with new standards in math, ELA and science<br />

and an overt directive to include engineering in grades<br />

K-12, educators, administrators, parents and education<br />

product developers should anticipate a whole new cycle of<br />

curriculum development and assessment design, as well as<br />

debates about accountability and effectiveness. Whether<br />

these are viewed as opportunities or as challenges,<br />

remember that at the heart of the discussion remains<br />

improving education for our youth.<br />

Doug Haller is the principal of Haller STEM Education<br />

Consulting. Haller is an education consultant specializing<br />

in strategic planning and market analysis to drive design,<br />

development and sales of niche education products for<br />

clients in the for-profit, nonprofit, and education and<br />

public outreach fields. His creative approach is based on<br />

years of practical experience as an educator, instructional<br />

designer and education consultant. Check out his blog,<br />

STEM Education: Inspire, Engage, Educate.<br />

Upcoming Science Olympiad Events<br />

PC West Science Olympiad Tournament<br />

(Divisions B and C)...................................<strong>December</strong> 15<br />

Norman Science Olympiad Tournament<br />

(Divisions B and C)....................................January 9<br />

<strong>Putnam</strong> <strong>City</strong> Elementary School (Division A) Science<br />

Olympiad Tournament, PC High ...............January 26<br />

<strong>Putnam</strong> <strong>City</strong> High School Science Olympiad Tournament<br />

(Divisions B and C)....................................February 2<br />

(tentative)<br />

Oklahoma State Science Olympiad Tournament<br />

(Divisions B and C) UCO.........................March 2<br />

Curriculum reView <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

9

Oklahoma School Testing Program<br />

<strong>2012</strong> – 2013 Test Dates<br />

State Law Title 70 O.S. § 1210.508 and Federal Law H.R. 1<br />

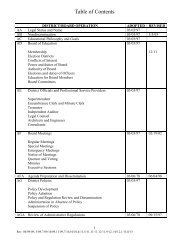

Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 Secondary Level<br />

End-of-Instruction (EOI)<br />

Oklahoma Core<br />

Curriculum Tests<br />

(OCCT)<br />

Mathematics and<br />

Reading<br />

Oklahoma Modified<br />

Alternate Assessment<br />

Program (OMAAP)<br />

Mathematics and<br />

Reading<br />

Oklahoma Core<br />

Curriculum Tests<br />

(OCCT)<br />

Mathematics and<br />

Reading<br />

Oklahoma Modified<br />

Alternate Assessment<br />

Program (OMAAP)<br />

Mathematics and<br />

Reading<br />

Oklahoma Core<br />

Curriculum Tests<br />

(OCCT)<br />

Writing; Reading,<br />

Mathematics,<br />

Science, and U.S.<br />

History<br />

Oklahoma Modified<br />

Alternate Assessment<br />

Program (OMAAP)<br />

Mathematics,<br />

Reading, and Science<br />

Oklahoma Core<br />

Curriculum Tests<br />

(OCCT)<br />

Mathematics and<br />

Reading<br />

Oklahoma Modified<br />

Alternate Assessment<br />

Program (OMAAP)<br />

Mathematics and<br />

Reading<br />

Oklahoma Core<br />

Curriculum Tests<br />

(OCCT)<br />

Mathematics,<br />

Reading, and<br />

Geography<br />

Oklahoma Modified<br />

Alternate Assessment<br />

Program (OMAAP)<br />

Mathematics and<br />

Reading<br />

Oklahoma Core<br />

Curriculum Tests<br />

(OCCT)<br />

Writing; Reading,<br />

Mathematics, Science,<br />

and U. S. History<br />

Oklahoma Modified<br />

Alternate Assessment<br />

Program (OMAAP)<br />

Mathematics, Reading,<br />

and Science<br />

Oklahoma Core Curriculum Tests (OCCT)<br />

ACE Algebra I, ACE Algebra II, ACE Biology I, ACE English II,<br />

ACE English III, ACE Geometry, and ACE U.S. History<br />

Oklahoma Modified Alternate Assessment Program (OMAAP)<br />

Algebra I, English II, Biology I, and U.S. History<br />

Multiple-Choice<br />

Testing Window:<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 10, 2013 –<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 24, 2013<br />

Multiple-Choice<br />

Testing Window:<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 10, 2013 –<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 24, 2013<br />

Writing Test Date:<br />

Wednesday, April 3<br />

and Thursday,<br />

April 4, 2013<br />

Multiple-Choice<br />

Testing Window:<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 10, 2013 –<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 24, 2013<br />

Multiple-Choice<br />

Testing Window:<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 10, 2013 –<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 24, 2013<br />

Online testing window<br />

for Grade 6<br />

Mathematics and<br />

Reading is extended<br />

through Friday, May 3,<br />

2013, for flexibility in<br />

scheduling computer<br />

time.<br />

Multiple-Choice<br />

Testing Window:<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 10, 2013 –<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 24, 2013<br />

Online testing<br />

window for Grade 7,<br />

Mathematics,<br />

Reading, and<br />

Geography is<br />

extended through<br />

Friday, May 3, 2013,<br />

for flexibility in<br />

scheduling computer<br />

time.<br />

Writing Test Date:<br />

Wednesday, April 3<br />

and Thursday, April 4,<br />

2013<br />

Multiple-Choice<br />

Testing Window:<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 10, 2013 –<br />

Wednesday,<br />

April 24, 2013<br />

Online testing window<br />

for Grade 8<br />

Mathematics and<br />

Reading is extended<br />

through Friday, May3,<br />

2013, for flexibility in<br />

scheduling computer<br />

time.<br />

Winter:<br />

Optional Retest Window (OCCT online tests only)<br />

Monday, November 19 – Friday, November 30, <strong>2012</strong><br />

Multiple-Choice Testing Window<br />

Paper/pencil accommodation Monday, <strong>December</strong> 3, <strong>2012</strong> – Friday,<br />

<strong>December</strong> 21, <strong>2012</strong><br />

Online is extended through Friday, January 11, 2013<br />

Writing Test on Tuesday, <strong>December</strong> 11 and Wednesday, <strong>December</strong><br />

12, <strong>2012</strong><br />

Trimester:<br />

Multiple-Choice Testing Window<br />

Paper/pencil accommodation: Monday, January 21, 2013 – Friday,<br />

February 8, 2013<br />

Online is extended through Friday, February 15, 2013<br />

Writing Test on Tuesday, January 29 and Wednesday, January 30,<br />

2013.<br />

Spring:<br />

Optional Retest Window (OCCT online tests only)<br />

Monday, April 1, 2013 – Friday, April 12, 2013<br />

Multiple-Choice Testing Window<br />

Paper/pencil accommodation: Monday, April 15, 2013 – Friday, May<br />

3, 2013<br />

Online is extended through Friday, May 10, 2013<br />

Writing Test on Tuesday, April 23, and Wednesday, April 24, 2013<br />

Summer: Monday, June 3, 2013 through Friday, August 2, 2013<br />

Note: March 18-22, 2013, Suggested Coordinated Spring Break Week<br />

Curriculum reView <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

10

Calendar of Meaningful Dates by www.xkcd.com<br />

Curriculum reView <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

11