to download a low resolution preview of this article - Roast Magazine

to download a low resolution preview of this article - Roast Magazine

to download a low resolution preview of this article - Roast Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

the<br />

Certification<br />

CONUNDRUM<br />

Are c<strong>of</strong>fee certifications still important?<br />

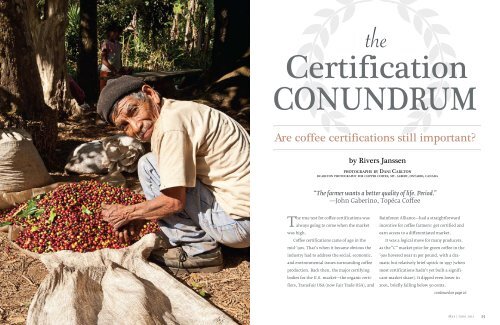

by Rivers Janssen<br />

p h o t o g r a p h s b y Da n i Ca r lt o n<br />

d c a r lt o n p h o t o g r a p h y f o r clipper c<strong>of</strong>fee, m t . a l b e rt , o n t a r i o, c a n a d a<br />

“The farmer wants a better quality <strong>of</strong> life. Period.”<br />

—John Gaberino, Topéca C<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

The true test for c<strong>of</strong>fee certifications was<br />

always going <strong>to</strong> come when the market<br />

was high.<br />

C<strong>of</strong>fee certifications came <strong>of</strong> age in the<br />

mid-’90s. That’s when it became obvious the<br />

industry had <strong>to</strong> address the social, economic,<br />

and environmental issues surrounding c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

production. Back then, the major certifying<br />

bodies for the U.S. market—the organic certifiers,<br />

TransFair USA (now Fair Trade USA), and<br />

Rainforest Alliance—had a straightforward<br />

incentive for c<strong>of</strong>fee farmers: get certified and<br />

earn access <strong>to</strong> a differentiated market.<br />

It was a logical move for many producers,<br />

as the “C” market price for green c<strong>of</strong>fee in the<br />

’90s hovered near $1 per pound, with a dramatic<br />

but relatively brief uptick in 1997 (when<br />

most certifications hadn’t yet built a significant<br />

market share). It dipped even <strong>low</strong>er in<br />

2001, briefly falling be<strong>low</strong> 50 cents.<br />

continued on page 26<br />

May | June 2011 25

The Certification Conundrum: Are C<strong>of</strong>fee Certifications Still Important? (continued)<br />

For c<strong>of</strong>fee farmers earning well be<strong>low</strong> the cost <strong>of</strong><br />

production, a potential premium <strong>of</strong> several cents per<br />

pound was at least a lifeline, and many were willing <strong>to</strong><br />

take on the additional labor, cost and risk <strong>of</strong> certifications<br />

in hopes <strong>of</strong> making a better living.<br />

But fundamentals change, and as <strong>of</strong> <strong>this</strong> writing,<br />

the “C” price is around $2.64 per pound. Even 18<br />

months ago, the price was $1.60, well above the $1.51<br />

Fair Trade USA floor price for certified organic c<strong>of</strong>fee.<br />

And there’s no sign yet that the market is retreating.<br />

Suddenly, some roasters and importers are wondering<br />

whether certifications hold the same relevance<br />

they did just a few years ago.<br />

It’s a difficult question, because few roasters disagree<br />

with the goals <strong>of</strong> the certifying bodies, even if<br />

they don’t always agree with the specific standards or<br />

strategies. But they also understand that growers by<br />

and large have one overriding goal: improving their<br />

quality <strong>of</strong> life. And if the rewards <strong>of</strong> the commodities<br />

market are significant—or a coyote is <strong>of</strong>fering cash<br />

up front for a crop that otherwise wouldn’t pay <strong>of</strong>f for<br />

months—it’s easy <strong>to</strong> see why a farmer would think the<br />

cost and labor <strong>of</strong> a certification isn’t worth the benefits.<br />

All in all, it’s an interesting time for certifications.<br />

High Demand, Low Supply<br />

Pricing complexities aside, demand for certified c<strong>of</strong>fees still appears<br />

strong in both the U.S. and other major c<strong>of</strong>fee markets. In 2010’s Trends in<br />

the Trade <strong>of</strong> Certified C<strong>of</strong>fees, authors Daniele Giovannucci, Joost Pierrot and<br />

Alexander Kasterine report that 16 percent <strong>of</strong> all 2009 U.S. c<strong>of</strong>fee imports<br />

had at least one certification, as compared <strong>to</strong> 8 percent worldwide.<br />

Whereas certified c<strong>of</strong>fee was once considered a small market niche,<br />

the authors say that’s no longer the case. The report did not indicate,<br />

however, how many <strong>of</strong> these c<strong>of</strong>fees were actually marketed by roasters<br />

as certified, as those numbers are more difficult <strong>to</strong> track.<br />

Each <strong>of</strong> the certifications is enjoying individual growth as well.<br />

According <strong>to</strong> the authors, sales <strong>of</strong> certified fair-trade c<strong>of</strong>fee increased by<br />

10 percent in the North American market (including Canada) from 2008<br />

<strong>to</strong> 2009, thanks in large part <strong>to</strong> Fair Trade USA’s ongoing relationship<br />

with such large roasters as Starbucks and Green Mountain C<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

<strong>Roast</strong>ers. Certified organic c<strong>of</strong>fee, which enjoys the best consumer<br />

recognition <strong>of</strong> any seal, increased nearly 5 percent in the same period.<br />

By contrast, the conventional c<strong>of</strong>fee segment is growing at roughly 2<br />

percent per year.<br />

The strongest growth, however, came from the Rainforest Alliance,<br />

which reported a 28-percent boost in North American imports from 2008<br />

<strong>to</strong> 2009. With Nespresso committing <strong>to</strong> a long-term relationship with<br />

Rainforest Alliance, and Caribou C<strong>of</strong>fee pledging <strong>to</strong> <strong>of</strong>fer 100 percent<br />

Rainforest Alliance-certified c<strong>of</strong>fee by the end <strong>of</strong> 2011, imports are<br />

expected <strong>to</strong> continue growing in both Europe and North America.<br />

Other certification schemes remain well behind these in the<br />

North American market but are growing as well. UTZ Certified<br />

accounted for 85,000 bags <strong>of</strong> c<strong>of</strong>fee in North America in 2009—as<br />

compared <strong>to</strong> 636,917 bags for fair trade, 703,080 bags for organic, and<br />

432,035 bags for Rainforest Alliance. UTZ Certified is a huge player in<br />

Europe, however, accounting for 1,155,000 bags in 2009.<br />

Smithsonian Bird-Friendly, which is <strong>of</strong>ten considered a subset <strong>of</strong><br />

organic, accounted for 1,600 bags in the United States in 2008 (the<br />

last year for which data is available). Similarly, the biodynamic label<br />

Demeter accounted for exports <strong>of</strong> 5,000 bags in 2009, with markets<br />

spread between Germany, Switzerland and the United States.<br />

Even in a struggling economy, demand for certified c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

among consumers still looks strong.<br />

Supply, on the other hand, is tightening.<br />

Al Liu, a trader/specialist in certified c<strong>of</strong>fees for Seattle’s Atlas<br />

C<strong>of</strong>fee Importers, says small farms and co-ops are being pressured<br />

<strong>to</strong> sell their certified c<strong>of</strong>fees <strong>to</strong> the conventional market, whether<br />

through coyotes at the farm gate or large companies with significant<br />

buying power. The strong “C” market is intensifying pressure on all<br />

sides <strong>to</strong> procure c<strong>of</strong>fee by whatever means possible.<br />

This pressure is a particular concern among fair-trade co-ops,<br />

which negotiate contracts at the co-op level yet rely on individual coop<br />

members <strong>to</strong> fulfill the contracts. If those farmers are <strong>of</strong>fered more<br />

attractive terms by coyotes—and in many cases, a more attractive<br />

<strong>of</strong>fer means up-front<br />

cash, not necessarily<br />

more money—the co-op<br />

can be left high and dry.<br />

Because small farmers<br />

generally lack the<br />

financing <strong>to</strong> get c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

<strong>to</strong> market efficiently,<br />

they’re <strong>of</strong>ten receptive<br />

<strong>to</strong> outside <strong>of</strong>fers.<br />

“If producer members don’t deliver, co-ops can’t export that<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fee as certified fair trade,” explains Liu. “Instead, the c<strong>of</strong>fee is<br />

sold <strong>to</strong> coyotes and disappears in<strong>to</strong> the conventional market. So the<br />

demand is still there and will continue <strong>to</strong> grow, but the supply—<br />

especially right now—can get really tight.”<br />

Producers and cooperatives also take on other risks when they<br />

pursue certifications. For one, there’s no guarantee they’ll find<br />

buyers for their certified c<strong>of</strong>fees. That means they’ll either have <strong>to</strong><br />

sell the c<strong>of</strong>fee <strong>to</strong> the conventional market or risk holding past-crop<br />

certified c<strong>of</strong>fee in hopes a buyer will eventually turn up. This makes<br />

some farmers even more receptive <strong>to</strong> up-front <strong>of</strong>fers from coyotes.<br />

Randy Wirth, the co-owner and roastmaster at Caffe Ibis C<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

<strong>Roast</strong>ing Company in Logan, Utah, is a big believer in the basis<br />

<strong>of</strong> fair trade: democratically run cooperatives, making sure that<br />

continued on page 28<br />

26 roast May | June 2011 27

The Certification Conundrum: Are C<strong>of</strong>fee Certifications Still Important? (continued)<br />

farmers receive a set percentage <strong>of</strong> the price,<br />

no child labor, women getting paid equal <strong>to</strong><br />

men for the same work. “These issues are<br />

as important now as they ever were,” says<br />

Wirth. He’s concerned, however, at the<br />

prospect <strong>of</strong> losing certified c<strong>of</strong>fees he’s already<br />

promised <strong>to</strong> cus<strong>to</strong>mers—a situation that<br />

buyers face whenever there is a strong “C”<br />

market.<br />

“It’s discouraging for a roaster who’s<br />

worked for many years with a specific farm<br />

group <strong>to</strong> all <strong>of</strong> a sudden not be able <strong>to</strong> get the<br />

group’s c<strong>of</strong>fee, or <strong>to</strong> receive poorer quality<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fee because your <strong>to</strong>p farmers are selling<br />

elsewhere,” he says. Wirth understands the<br />

challenges faced by the small farmer, noting<br />

that “it’s <strong>to</strong>ugh on the ground in these rural<br />

co-ops,” which are sometimes located in<br />

remote areas hours by car (on dirt roads)<br />

from the nearest city. At the same time,<br />

he believes there have <strong>to</strong> be remedies<br />

<strong>to</strong> prevent growers from defaulting on<br />

contracts, whether it’s sanctions on<br />

the part <strong>of</strong> fair-trade certifiers or an<br />

agreement by brokers <strong>to</strong> no longer buy<br />

from certain farms.<br />

Rodney North, the media<br />

coordina<strong>to</strong>r for the Massachusetts-based<br />

fair-trade roaster Equal Exchange,<br />

says there are a number <strong>of</strong> “complex<br />

and nuanced” ways <strong>to</strong> handle co-op<br />

defaults, but the most common is <strong>to</strong><br />

renegotiate the contract. In a period<br />

<strong>of</strong> contracting supply, it’s difficult for<br />

many roasters <strong>to</strong> completely terminate<br />

buying relationships that have paid <strong>of</strong>f<br />

in the past.<br />

Wirth notes, however, that defaults<br />

are not the norm; many <strong>of</strong> his farm<br />

groups are still honoring their contracts<br />

and standing behind their co-ops 100<br />

percent. But “when it’s bad, it’s really<br />

bad,” he says.<br />

Liu says certified-organic c<strong>of</strong>fees<br />

face similar issues, especially at the<br />

small farm and co-op level, where many<br />

fair-trade c<strong>of</strong>fees are also certifiedorganic.<br />

He notes that he hasn’t seen<br />

as much scrambling among Rainforest<br />

Alliance c<strong>of</strong>fees. “I think that’s in large<br />

part because most Rainforest-certified<br />

producers are estates, and they aren’t<br />

battling a situation where coyotes are<br />

roaming around trying <strong>to</strong> buy c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

from the estate owners,” Liu continues.<br />

“The Rainforest market just isn’t<br />

structured that way.”<br />

Of course, supply issues aren’t<br />

restricted <strong>to</strong> certified c<strong>of</strong>fees, which<br />

roasters know all <strong>to</strong>o well. The higher<br />

the “C” price, the less incentive a<br />

farmer has <strong>to</strong> preserve high-quality<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fees for the specialty market. As Tim<br />

Chapdelaine, the sales manager for Café<br />

Imports in Saint Paul, Minn., explains:<br />

“You have <strong>to</strong> take [potentially great<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fees], set them aside, send them<br />

through a culling process, determine<br />

whether they’re special, and then select<br />

the good ones that meet the higherquality<br />

criteria. And the buyer … has <strong>to</strong><br />

say, ‘Yes, I’ll pay you a big premium for<br />

that.’ In <strong>this</strong> market, the incentive is<br />

not as high as it was before.”<br />

Wirth says a huge key <strong>to</strong> protecting<br />

contracts is communication: between<br />

the certifying bodies, farmers, coops,<br />

roasters, importers and any other<br />

principals. All parties need <strong>to</strong> be on the<br />

same page—a process that takes time,<br />

effort, and an appreciation for the<br />

challenges faced by others in the supply<br />

chain.<br />

Monika Firl, producer relations<br />

manager for a 23-member c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

importing group called Cooperative<br />

C<strong>of</strong>fees with <strong>of</strong>fices in Montreal and<br />

Americus, Ga., has a similar take. She<br />

says that on-the-ground relationships<br />

are essential when supply is tight.<br />

“When you have an up market, that’s<br />

when the relationship itself is going <strong>to</strong><br />

be tested,” says Firl. “If you have a good<br />

relationship, and the buyer and seller<br />

are concerned about each other, the<br />

price starts <strong>to</strong> fol<strong>low</strong>. But when price is<br />

the only thing you’re focused on, the<br />

challenge is greater. So much depends<br />

on trust, communication, and the<br />

assistance you can <strong>of</strong>fer with hurdles<br />

like financing. You have <strong>to</strong> go an extra<br />

mile or two.”<br />

Wanting<br />

What’s Best<br />

for the Farmer<br />

“Higher prices per pound are only part<br />

<strong>of</strong> the equation,” says John Gaberino,<br />

owner <strong>of</strong> Topéca C<strong>of</strong>fee. Gaberino has a<br />

personal interest in both the growing<br />

and consuming sides <strong>of</strong> the industry,<br />

as his family runs a roastery in Tulsa,<br />

Okla., and a c<strong>of</strong>fee farm in El Salvador.<br />

“We in the industry normally talk about<br />

how <strong>to</strong> increase the price per pound,<br />

but we should really be talking about<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>it per pound. It doesn’t do the farmer<br />

any good <strong>to</strong> change his growing and<br />

processing methods if he increases his<br />

average sales price by 30 percent but<br />

increases his expenses by 50 percent.”<br />

Gaberino’s assertion brings <strong>to</strong><br />

mind a few additional questions about<br />

certifications: Are they accomplishing<br />

their goal? Are they putting farmers in a<br />

more economically secure position and<br />

leading <strong>to</strong> better environmental and<br />

social outcomes? Are they a net positive<br />

for the specialty c<strong>of</strong>fee industry?<br />

The term “hornet’s nest” was<br />

invented for just such an occasion.<br />

In 2008’s Seeking Sustainability report,<br />

Daniele Giovannucci and Jason Potts discuss<br />

a methodical framework that grapples with<br />

the questions, while making clear that<br />

they’re merely reporting observations and<br />

not making conclusions. It’s worth noting<br />

that the report came out prior <strong>to</strong> the current<br />

market run-up.<br />

Among their findings: A majority (60<br />

percent) <strong>of</strong> the certified farms surveyed<br />

reported an improved economic outlook after<br />

certification, despite 62 percent <strong>of</strong> the farms<br />

reporting <strong>low</strong>er yields. A slight majority (54<br />

percent) <strong>of</strong> farms reported improved market<br />

access due <strong>to</strong> certification. However, even<br />

though certified farms on the whole had<br />

better pollution management systems,<br />

continued on page 30<br />

28 roast May | June 2011 29

The Certification Conundrum: Are C<strong>of</strong>fee Certifications Still Important? (continued)<br />

it wasn’t possible (yet) <strong>to</strong> detect significant improvements in<br />

biodiversity or soil health.<br />

One inescapable observation was that certified farms have better<br />

social systems in place. According <strong>to</strong> Seeking Sustainability, four times<br />

as many certified farms have set up occupational health and safety<br />

policies, and certified farms use written employment contracts twice<br />

as <strong>of</strong>ten as conventional farms.<br />

The authors make clear, however, that it’s way <strong>to</strong>o early <strong>to</strong> make<br />

definitive statements on the long-term impact <strong>of</strong> certifications: “An<br />

apt analogy may be that we have designed a class <strong>of</strong> medicines, but<br />

are not really certain <strong>of</strong> their full impact or <strong>to</strong> what extent they may<br />

have unintended side effects.”<br />

Talk <strong>to</strong> roasters, importers, and growers and you’ll get a much<br />

more personal view. Often, the concerns are long standing, echoing<br />

complaints that first arose over a decade ago. Rainforest Alliance has<br />

long faced criticism for al<strong>low</strong>ing its seal on c<strong>of</strong>fees that contain as<br />

little as 30 percent <strong>of</strong> certified beans, although that’s due <strong>to</strong> change<br />

soon. The organization’s new standards will require all c<strong>of</strong>fees with<br />

the Rainforest Alliance seal <strong>to</strong> scale up a minimum <strong>of</strong> 15 percent per<br />

year until they reach 100-percent certified content. This includes<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fees that start at 30-percent certified content as well as c<strong>of</strong>fees<br />

that start at 90 percent.<br />

Gaberino isn’t a fan <strong>of</strong> Fair Trade USA’s marketing approach,<br />

which he believes is misleading <strong>to</strong> consumers. “Ninety-nine percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> the consumers I’ve ever talked <strong>to</strong> don’t realize that not all farms<br />

can be fair-trade-certified, and that the organization’s goal is <strong>to</strong><br />

focus specifically on small family farms and co-ops,” he says. While<br />

calling the small-farmer focus “clearly very admirable,” he bristles at<br />

the implication that non-co-op c<strong>of</strong>fees are unfairly traded.<br />

The cost <strong>of</strong> certifications remains a sticking point, as does the<br />

legwork that <strong>of</strong>ten seems incomprehensible <strong>to</strong> the farmer. And<br />

many c<strong>of</strong>fee pr<strong>of</strong>essionals believe that certifications amount <strong>to</strong><br />

subsidies that dis<strong>to</strong>rt traditional market incentives.<br />

When asked how most farmers react when she brings up<br />

certifications, Firl says they’re rarely enthusiastic. “Usually, there’s<br />

sort <strong>of</strong> a long groan,” she says. “I think the biggest challenge for the<br />

farmers is that the criteria are <strong>of</strong>ten established from someone’s<br />

desk, using language that’s unintelligible <strong>to</strong> them. Half <strong>of</strong> the<br />

challenge <strong>of</strong> the certification is the anxiety <strong>of</strong> trying <strong>to</strong> understand<br />

what’s even going <strong>to</strong> be inspected. Add the cost and you have a large<br />

burden for farmers.”<br />

That’s not <strong>to</strong> say farmers are anti-certification, per se. Like any<br />

diverse group <strong>of</strong> people, opinions vary dramatically. Some see the<br />

cost <strong>of</strong> certification as a necessary investment in building market<br />

access, while others<br />

think certifications<br />

are <strong>to</strong>o much hassle.<br />

Some are committed <strong>to</strong><br />

a specific certification<br />

because they believe<br />

in the certification’s<br />

methodology or goals.<br />

And many others are<br />

simply <strong>to</strong>o far removed<br />

from the certification<br />

process—whether because<br />

<strong>of</strong> location, financial<br />

situation, or other reasons—<strong>to</strong><br />

pursue certification at all.<br />

Firl is also concerned that<br />

certifications such as fair trade<br />

are becoming a bit <strong>to</strong>o broad<br />

as they increasingly work<br />

with larger companies. “My<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> fair trade is<br />

that we’re trying <strong>to</strong> tighten the<br />

relationship between farmers<br />

and consumers,” she explains.<br />

“That means bridging the<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> what it takes<br />

<strong>to</strong> produce a good cup <strong>of</strong> c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

and educating consumers on the challenges that smallholders face<br />

constantly. But what I see happening over the last 10 years is that<br />

we’re losing the communication as opposed <strong>to</strong> strengthening it.”<br />

Firl uses the example <strong>of</strong> a talk she recently gave at a local college,<br />

where she held up a bag <strong>of</strong> fair-trade-certified c<strong>of</strong>fee. The problem,<br />

she says, was that the fair-trade label was the only identifying<br />

mark on the c<strong>of</strong>fee other than the brand name. “I didn’t know what<br />

country it came from, and I certainly didn’t know what co-op it came<br />

from,” she says. “Unless I’m a student <strong>of</strong> fair trade and know exactly<br />

what criteria is used for the label, I don’t know what’s behind the<br />

bag <strong>of</strong> c<strong>of</strong>fee in a trading sense either.”<br />

Firl says she’s not opposed <strong>to</strong> large companies entering the fairtrade<br />

arena, but she’s concerned that they’ll dilute the fair-trade<br />

process by making volume more important than standards and<br />

information.<br />

Chapdelaine takes a broader view. He says that people tend <strong>to</strong><br />

view certifications through an absolutist lens: either a certification<br />

is the ultimate answer or it isn’t. But he maintains that there’s no<br />

savior in c<strong>of</strong>fee, and that all certifications—whatever their faults—<br />

contribute value. In fact, he says the specialty c<strong>of</strong>fee industry is<br />

fortunate compared <strong>to</strong> most industries.<br />

“If you look at other industries, big companies just create their<br />

own certifications or own them wholly,” Chapdelaine says. “Ours are<br />

actually independent. There’s not one individual company that has<br />

the power <strong>to</strong> alter a certification significantly in its favor. We’re a<br />

uniquely healthy industry in that sense.”<br />

And while he’s a big proponent <strong>of</strong> quality control, Chapdelaine<br />

also points out that certifications add value <strong>to</strong> a c<strong>of</strong>fee independent<br />

<strong>of</strong> its quality, which is important because even the most successful<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fee co-ops and estates can’t sell all their c<strong>of</strong>fee <strong>to</strong> the highend<br />

specialty market. “A farmer needs <strong>to</strong> sell all <strong>of</strong> the c<strong>of</strong>fee he<br />

produces, and if he can raise the price on some <strong>of</strong> the acceptable<br />

qualities that aren’t true specialty, then he can get ahead,” he says.<br />

Certifications, Quality and<br />

Direct Trade<br />

Aside from associated environmental and social benefits, certified<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fees also <strong>of</strong>fer a tangible benefit <strong>to</strong> quality-oriented roasters:<br />

process and traceability. With certification comes documentation,<br />

and with documentation comes increased attention <strong>to</strong> detail.<br />

continued on page 32<br />

30 roast May | June 2011 31

The Certification Conundrum: Are C<strong>of</strong>fee Certifications Still Important? (continued)<br />

While not a fan <strong>of</strong> every certification, Jim Kossolos, the coowner<br />

<strong>of</strong> San Cris<strong>to</strong>bal C<strong>of</strong>fee Importers in Kirkland, Wash., says<br />

certifications in general have the potential <strong>to</strong> improve production<br />

standards over the long haul, which could eventually lead <strong>to</strong> more<br />

consistent c<strong>of</strong>fee quality. “All certifications force a measure <strong>of</strong> order<br />

in<strong>to</strong> an otherwise chaotic system driven by commodities pricing,”<br />

explains Kossolos. “The ‘order’ in many cases is directly related <strong>to</strong><br />

process control improvement, which leads inevitably <strong>to</strong> quality<br />

improvement.”<br />

Put another way, farmers have <strong>to</strong> assert more control <strong>of</strong> the<br />

process before they can start improving c<strong>of</strong>fee quality or boosting<br />

market access. Certifications are one way that farmers can gain<br />

that control over time, usually in conjunction with a buyer who<br />

negotiates process improvements in<strong>to</strong> a contract. Direct trade is<br />

another, as farmers in direct-trade relationships generally work with<br />

roasters <strong>to</strong> meet specific production standards.<br />

Liu says a number <strong>of</strong> the small- <strong>to</strong> mid-sized roasters he works<br />

with have dropped out <strong>of</strong> the Fair Trade USA licensing program in<br />

favor <strong>of</strong> direct-trade relationships, while some larger roasters have<br />

simultaneously increased their fair-trade volume. Liu noted that<br />

many <strong>of</strong> these smaller roasters are still sourcing from fair-tradecertified<br />

cooperatives (and paying the social premium), but are<br />

no longer paying the Fair Trade USA licensing fee, meaning they<br />

can’t use the <strong>of</strong>ficial fair trade seal. In essence, Liu says, they’re<br />

supporting fair-trade values on the origin side—<strong>of</strong>ten <strong>to</strong> preserve<br />

relationships with certain co-ops—but are comfortable marketing<br />

the c<strong>of</strong>fee through other means.<br />

Cooperative C<strong>of</strong>fee’s roaster members are taking a similar path.<br />

Rather than buying through Fair Trade USA, Cooperative C<strong>of</strong>fees is<br />

relying on Fair Trade Pro<strong>of</strong>, a third-party transparency site. The coop<br />

puts all contracts and verification up on the site so that anyone<br />

can learn the c<strong>of</strong>fee’s path and price.<br />

Firl says Cooperative C<strong>of</strong>fees is sort <strong>of</strong> a fair-trade/direct-trade/<br />

farmer-friendly hybrid. “Humanizing trade is important,” she says,<br />

“and the only way you can do that is having direct contact, so you<br />

can understand the challenges the other side is facing.”<br />

Chapdelaine says it’s part <strong>of</strong> an overall awareness within the<br />

specialty c<strong>of</strong>fee industry that quality must extend throughout the<br />

entire supply chain, because even a little bit <strong>of</strong> efficiency can go<br />

a long way. “Just expediting the movement <strong>of</strong> the c<strong>of</strong>fee from the<br />

grower <strong>to</strong> the roaster can put a lot more money in the farmer’s<br />

pocket,” he says. That doesn’t mean forgoing the time-consuming<br />

steps required <strong>to</strong> produce high-end c<strong>of</strong>fees, but making sure<br />

those steps are part <strong>of</strong> a rewarding relationship for all the parties<br />

involved, and with as few<br />

uncertainties as possible.<br />

But direct trade is also<br />

limited <strong>to</strong> a large degree by<br />

the amount <strong>of</strong> work required<br />

<strong>to</strong> build a successful directtrade<br />

program. Wirth loves<br />

direct trade, but he says<br />

there’s no way he could<br />

personally visit all the farms<br />

he buys from, let alone learn<br />

enough about the farms <strong>to</strong><br />

evaluate the environmental<br />

and social conditions on the<br />

ground.<br />

“We import from 26<br />

countries,” he says. “In<br />

northern Peru, I’d have <strong>to</strong><br />

spend 60 hours behind the<br />

wheel <strong>of</strong> a car on really bad<br />

roads just <strong>to</strong> visit our farms.<br />

That doesn’t include any<br />

processing facilities in the<br />

area. And that’s just one<br />

region.” To Wirth, direct-trade<br />

relationships must include<br />

personal farm visits and a<br />

fairly thorough understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> the farm’s day-<strong>to</strong>-day<br />

operations.<br />

Importers such as Cooperative C<strong>of</strong>fees, Café Imports and Atlas<br />

C<strong>of</strong>fee Importers all support roasters’ direct-trade relationships<br />

<strong>to</strong> different degrees. Sometimes they help facilitate relationships<br />

between roasters and farmers, other times they assist with qualityimprovement<br />

projects, and sometimes they simply help the farmer<br />

efficiently move the c<strong>of</strong>fee after it leaves the farm (all these tasks are<br />

generally defined in the roaster/importer contract).<br />

But even with importer support, it’s a major logistical<br />

undertaking. “I think some people are treating direct trade like<br />

they did fair trade 10 or 11 years ago—like <strong>this</strong> is the answer,” says<br />

Chapdelaine. “But It doesn’t happen until after a period <strong>of</strong> time and<br />

a certain volume <strong>of</strong> c<strong>of</strong>fee,” he says. “My recommendation is always<br />

<strong>to</strong> put the energy in<strong>to</strong> the relationship and then find good partners<br />

<strong>to</strong> help with milling, exporting and importing <strong>to</strong> keep the high-end<br />

products moving.”<br />

In addition, Liu points out that direct-trade and certified c<strong>of</strong>fees<br />

aren’t mutually exclusive. “You can do direct trade with fair trade,<br />

Rainforest Alliance, and organic c<strong>of</strong>fees, <strong>to</strong>o,” he says.<br />

Moving Forward<br />

The major c<strong>of</strong>fee certifiers aren’t just waiting <strong>to</strong> see how the<br />

market shakes out. Several are working on new initiatives <strong>to</strong> help<br />

farmers streamline the certification process or improve their process<br />

potential. In the interim, they’re highlighting the non-price<br />

premiums <strong>of</strong> certifications.<br />

Stacy Geagan Wagner, the direc<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> media and public<br />

relations for Fair Trade USA, says fair trade’s value extends far<br />

beyond a guaranteed floor price. “Fair trade has always been about<br />

giving farmers a voice in the process,” she says, citing the co-ops’<br />

democratic structures and transparency mechanisms. “Every<br />

member votes on what their communities need most <strong>to</strong> break the<br />

cycle <strong>of</strong> poverty, whether it’s improving education, health care, or<br />

productive capacity.”<br />

She says market access is another huge benefit, as Fair Trade USA<br />

provides once-marginalized small farmers with market information<br />

far beyond what they’d otherwise receive. The organization plans<br />

<strong>to</strong> bring more than 200 fair-trade farmers <strong>to</strong> the 2011 SCAA show <strong>to</strong><br />

meet potential buyers.<br />

continued on page 34<br />

32 roast May | June 2011 33

The Certification Conundrum (continued)<br />

At the same time, Geagan Wagner is up front<br />

about many <strong>of</strong> the challenges Fair Trade USA<br />

faces. The coyote issue and supply constraints<br />

are big impediments, she agrees. “We really<br />

have <strong>to</strong> keep talking with farmers about shortterm<br />

versus long-term benefits,” she continues,<br />

noting that the certifying agency is bringing in<br />

new cooperatives each month. She also says Fair<br />

Trade USA is working closely with domestic and<br />

international lenders <strong>to</strong> expand farmers’ access <strong>to</strong><br />

pre-harvest credit. “That’s so important.”<br />

Most intriguingly, Geagan Wagner says<br />

Fair Trade USA is open <strong>to</strong> doing some things<br />

differently than it has in the past. She says the<br />

organization is becoming more active in quality<br />

improvement, having worked with USAID<br />

and a couple <strong>of</strong> large c<strong>of</strong>fee companies <strong>to</strong> open<br />

cupping labs and provide agronomy training in<br />

Brazil. Fair Trade USA is even openly discussing<br />

whether <strong>to</strong> expand its reach beyond cooperatives. “We hear lots <strong>of</strong> complaints about<br />

non-cooperative farmers not being able <strong>to</strong> receive fair-trade certification,” she says. “So<br />

we’re asking ourselves, ‘How do we expand fair trade in c<strong>of</strong>fee? Do we look at other farm<br />

settings? Maybe even estate c<strong>of</strong>fees?’”<br />

And Geagan Wagner is forthright about the need for better communication with<br />

roasters and other c<strong>of</strong>fee pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. “We started as an activist community, but we’re<br />

now development pr<strong>of</strong>essionals focused on improving the lives <strong>of</strong> c<strong>of</strong>fee farmers,” she<br />

says. “We don’t want <strong>to</strong> create impact ourselves, but help the industry create impact.<br />

That means working in partnership with farmers, roasters and other people in the<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fee industry.”<br />

The Rainforest Alliance is in a different position than Fair Trade USA, having<br />

focused initially on certifying sizable c<strong>of</strong>fee estates rather than small farmers and coops.<br />

Sabrina Vigilante, the direc<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> sustainable value chains for the organization,<br />

says it’s difficult for the Rainforest Alliance <strong>to</strong> work with smallholders because so<br />

many <strong>of</strong> its standards are based on land use, which requires a defined area and an<br />

organized management strategy. Many smallholders aren’t in a position <strong>to</strong> manage the<br />

requirements by themselves, and still more are located in remote regions with limited<br />

access <strong>to</strong> certifiers.<br />

Vigilante says that the organization has been making progress on the smallholder<br />

front for the past several years, however. Small farmers generally need <strong>to</strong> band in<strong>to</strong><br />

some form <strong>of</strong> producer group <strong>to</strong> receive certification—not necessarily a co-op—and gain<br />

the support <strong>of</strong> a local entity, such as an exporter or development group. She says the<br />

funding for such projects has grown exponentially, including support from the UN<br />

Development Program.<br />

“It’s a big investment <strong>to</strong> work with the most disadvantaged farmers,” says<br />

Vigilante. “It doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a huge investment <strong>of</strong> time, and you’re<br />

working with different cultures<br />

with different sensitivities. It’s a<br />

long process.” Vigilante says the<br />

UN project is providing technical<br />

assistance <strong>to</strong> farmers through<br />

Rainforest Alliance certification,<br />

with a directive <strong>to</strong> improve the<br />

social, environmental and economic<br />

condition <strong>of</strong> smallholders in six<br />

Latin American countries. “That’s<br />

the biggest project we have in c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

right now, and it’s <strong>to</strong>tally focused on<br />

smallholders,” she says.<br />

“It’s funny how people’s residual impression defines you<br />

in a certain way,” says Vigilante, referring <strong>to</strong> the Rainforest<br />

Alliance’s reputation as a near-exclusive certifier <strong>of</strong> large<br />

estates. “Even when you adapt and change, you’re always<br />

characterized in that mold. But that’s OK.”<br />

As with Fair Trade USA, Vigilante says the Rainforest<br />

Alliance is continually updating its standards based on<br />

feedback from producers and other c<strong>of</strong>fee pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. She<br />

says the organization is also working with Fair Trade USA<br />

and the organic certifiers <strong>to</strong> strengthen certifications as a<br />

whole. “They’re not all the same, but when they do overlap,<br />

we can learn from one another.”<br />

Vigilante expects at least a moderately bumpy ride while<br />

the Rainforest Alliance adapts <strong>to</strong> high c<strong>of</strong>fee prices. She anticipates some farmers will<br />

leave the program because the premiums are <strong>to</strong>o <strong>low</strong>, while others will stay in it through<br />

thick and thin. Vigilante says one advantage <strong>of</strong> the Rainforest Alliance approach is that<br />

much <strong>of</strong> its demand is driven by partnerships with major roasters who have committed <strong>to</strong><br />

long-term buying relationships. Farmers or estates that leave the program risk sacrificing<br />

these relationships for the immediate rewards <strong>of</strong> a high market.<br />

Of the various certifications, UTZ Certified may be mixing things up the most.<br />

Founded in 1997 by the Dutch roaster Ahold C<strong>of</strong>fee Company and its Guatemalan<br />

suppliers, who didn’t qualify for fair-trade certification, UTZ Certified is little known in<br />

the United States. However, the organization is doing some interesting work at origin that<br />

stands <strong>to</strong> benefit both the specialty c<strong>of</strong>fee industry and other certifiers.<br />

First, UTZ has invested heavily in developing an online traceability system that links<br />

producers with traders and roasters. This “transparent marketplace,” as UTZ General<br />

Manager Graham Mitchell calls it, can trace different stages <strong>of</strong> quality while also<br />

notifying farmers <strong>of</strong> the premium others have received for similar c<strong>of</strong>fees. As Mitchell<br />

hypothesizes, “For a Guatemalan SHB screen size 12, farmers could look up the national<br />

average for the c<strong>of</strong>fee at ANACAFE and use that as a benchmark. Or they can look at the<br />

second window on Kenya and see what premiums Kenyan farmers received.” Mitchell<br />

expects the c<strong>of</strong>fee traceability system <strong>to</strong> launch in the third quarter <strong>of</strong> 2011.<br />

Second, UTZ works with third-party certifiers rather than acting as a certification<br />

body itself. “We train them on our code <strong>of</strong> conduct, but they’re basically competing for<br />

the farmers’ work at origin,” says Mitchell. The significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>this</strong> from UTZ’s perspective<br />

is that it gives farmers more certification flexibility, as these independent audi<strong>to</strong>rs could<br />

potentially combine an organic, UTZ, and even a direct-trade audit in<strong>to</strong> a single farm<br />

visit, saving a farmer both time and money.<br />

This leads in<strong>to</strong> UTZ’s idea for pre-certification. UTZ changed its code <strong>of</strong> conduct<br />

in 2009 <strong>to</strong> reward farmers for continuous improvement, requiring them <strong>to</strong> meet set<br />

miles<strong>to</strong>nes over a five-year period. Initially, the farm has <strong>to</strong> meet a baseline: no child<br />

labor, farmer housing, good land practices, a reliable record-keeping system, etc. As a<br />

farm gradually improves certain practices, UTZ will work with the farm <strong>to</strong> improve in<br />

other areas as well.<br />

This by itself isn’t a dramatic difference from other certifiers, as most do some<br />

development work at origin; and Rainforest Alliance has a similar philosophy on farms<br />

that show progressive improvement. However, UTZ’s pre-certification work would not be<br />

restricted <strong>to</strong> UTZ Certified farms. In fact, a farmer could use UTZ’s technical assistance as<br />

a way <strong>of</strong> pursuing other certifications over time, such as organic, fair trade or Rainforest<br />

Alliance. Most <strong>of</strong> the funding would not come from the farmers themselves, but from<br />

public and private grants and assistance from c<strong>of</strong>fee roasters.<br />

“We’d like it <strong>to</strong> act as a foundation,” explains Mitchell. “If a big farm group has one<br />

or two mills that want <strong>to</strong> be fair trade, we can support them. It they’re more interested in<br />

biodiversity, we could help them receive Rainforest Alliance certification. If they liked our<br />

path as a driver, they’d choose the UTZ certification. We see our practices as agronomycontinued<br />

on page 36<br />

34 roast May | June 2011 35

®<br />

The Certification Conundrum: Are C<strong>of</strong>fee Certifications Still Important? (continued)<br />

and business-based, helping farmers set up a good system from a<br />

productivity and training sense.”<br />

Mitchell also envisions roasters using UTZ <strong>to</strong> help with their<br />

direct-trade initiatives, perhaps using up-front investment from<br />

roasters <strong>to</strong> help build wet mills or improve post-harvesting practices<br />

on partner farms. Because UTZ works with trained agronomists in<br />

23 origins in addition <strong>to</strong> a variety <strong>of</strong> national c<strong>of</strong>fee boards, Mitchell<br />

in some ways considers UTZ more <strong>of</strong> a producers’ group than a<br />

traditional certifying agency.<br />

“Right now, if you push farmers <strong>to</strong>o hard on certification,<br />

they’re going <strong>to</strong> leave your program,” says Mitchell. “They really<br />

have <strong>to</strong> see the value in it in terms <strong>of</strong> their businesses. One <strong>of</strong> the<br />

strong points <strong>of</strong> our program is that we start at a very early stage<br />

with a farm, from <strong>to</strong>pography and variety all the way through<br />

picking and pruning and post-harvest practices. The value we want<br />

<strong>to</strong> provide farmers is productivity and green quality.”<br />

Tying It All Together<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the reasons UTZ is strongly focused on working with other<br />

certifications is <strong>to</strong> avoid stagnation within the c<strong>of</strong>fee industry. “We<br />

see it in other commodities, <strong>to</strong>o, like cocoa,” says Mitchell. “People<br />

had a lot <strong>of</strong> good intentions over the past 10 years, but they haven’t<br />

really solved a lot <strong>of</strong> the farmers’ problems.”<br />

“With all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

climate challenges<br />

and other concerns,<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fee pr<strong>of</strong>essionals<br />

are really worried<br />

about supply. And I<br />

think that’s going <strong>to</strong><br />

force the programs<br />

<strong>to</strong> work <strong>to</strong>gether,”<br />

Mitchell adds.<br />

“You can’t go <strong>to</strong> the<br />

farmer anymore<br />

with five different<br />

lists <strong>of</strong> requirements for five different programs. Those days are kind<br />

<strong>of</strong> numbered.”<br />

To that end, UTZ Certified, the international Fairtrade Labelling<br />

Organization (FLO) and the Rainforest Alliance/Sustainable<br />

Agriculture Network released a joint statement in February 2011. In<br />

the statement, the organizations committed <strong>to</strong> working <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>to</strong><br />

make the certifying process simpler and reduce costs for farmers.<br />

They’re also developing <strong>to</strong>ols and materials that make it easier for<br />

farmers <strong>to</strong> adhere <strong>to</strong> multiple standards at once.<br />

For his part, Chapdelaine is optimistic that certifications<br />

and direct trade can work <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>to</strong> make a positive difference<br />

for farmers, provided the c<strong>of</strong>fee industry continues <strong>to</strong> make it a<br />

priority. “C<strong>of</strong>fee has been most successful<br />

when you’ve had people who are willing<br />

<strong>to</strong> pay attention and work hard and be as<br />

equitable as possible,” he says. “That’s what<br />

a relationship does. It deals with problems<br />

succinctly and fairly, and looks forward <strong>to</strong><br />

advancing the needs <strong>of</strong> all parties in the<br />

situation.”<br />

As for what will happen <strong>to</strong> certified<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fees if the high “C” market holds, Liu and<br />

other sources say it’s really up in the air. Liu<br />

doesn’t think consumers have caught up<br />

<strong>to</strong> the implications <strong>of</strong> high “C” prices—or<br />

even that high prices exist—so he expects<br />

demand for certified c<strong>of</strong>fees <strong>to</strong> at least hold<br />

steady.<br />

Supply?<br />

“Good question.”<br />

Rivers Janssen is a freelance writer and<br />

edi<strong>to</strong>r based in Portland, Ore. He can be reached at<br />

riversjanssen@gmail.com.<br />

C e rt i f i c at i o n Re s o u r c e s<br />

Demeter<br />

www.demeter-usa.org<br />

Fair Trade USA<br />

www.fairtradeusa.org<br />

Organic<br />

www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/nop<br />

Rainforest Alliance<br />

www.rainforest-alliance.org<br />

Smithsonian Bird Friendly<br />

www.nationalzoo.si.edu/scbi/migra<strong>to</strong>rybirds<br />

UTZ Certified<br />

www.utzcertified.org<br />

36 roast May | June 2011 37