printer-friendly version (PDF) - Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy ...

printer-friendly version (PDF) - Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy ...

printer-friendly version (PDF) - Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

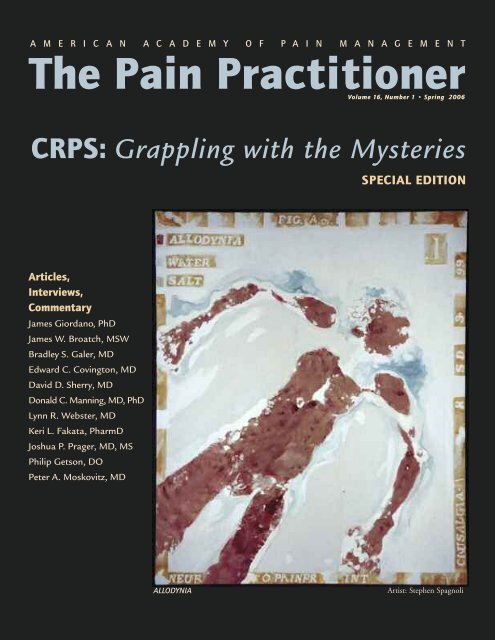

A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F P A I N M A N A G E M E N T<br />

The Pain Practitioner<br />

Volume 16, Number 1 • Spring 2006<br />

CRPS: Grappling with the Mysteries<br />

SPECIAL EDITION<br />

Articles,<br />

Interviews,<br />

Commentary<br />

James Giordano, PhD<br />

James W. Broatch, MSW<br />

Bradley S. Galer, MD<br />

Edward C. Covington, MD<br />

David D. Sherry, MD<br />

Donald C. Manning, MD, PhD<br />

Lynn R. Webster, MD<br />

Keri L. Fakata, PharmD<br />

Joshua P. Prager, MD, MS<br />

Philip Getson, DO<br />

Peter A. Moskovitz, MD<br />

ALLODYNIA<br />

Artist: Stephen Spagnoli

A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F P A I N M A N A G E M E N T<br />

The Pain Practitioner<br />

Volume 16, Number 1 • Spring 2006<br />

CRPS: Grappling with the Mysteries<br />

SPECIAL EDITION<br />

Articles,<br />

Interviews,<br />

Commentary<br />

James Giordano, PhD<br />

James W. Broatch, MSW<br />

Bradley S. Galer, MD<br />

Edward C. Covington, MD<br />

David D. Sherry, MD<br />

Donald C. Manning, MD, PhD<br />

Lynn R. Webster, MD<br />

Keri L. Fakata, PharmD<br />

Joshua P. Prager, MD, MS<br />

Philip Getson, DO<br />

Peter A. Moskovitz, MD<br />

ALLODYNIA<br />

Artist: Stephen Spagnoli

A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F P A I N M A N A G E M E N T<br />

The Pain Practitioner<br />

Volume 16, Number 1 • Spring 2006<br />

CRPS: Grappling with the Mysteries<br />

SPECIAL EDITION<br />

Articles,<br />

Interviews,<br />

Commentary<br />

James Giordano, PhD<br />

James W. Broatch, MSW<br />

Bradley S. Galer, MD<br />

Edward C. Covington, MD<br />

David D. Sherry, MD<br />

Donald C. Manning, MD, PhD<br />

Lynn R. Webster, MD<br />

Keri L. Fakata, PharmD<br />

Joshua P. Prager, MD, MS<br />

Philip Getson, DO<br />

Peter A. Moskovitz, MD<br />

ALLODYNIA<br />

Artist: Stephen Spagnoli

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S<br />

SPECIAL ISSUE CRPS: GR APPLING WITH THE MYSTERIES<br />

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Lennie Duensing<br />

CO-EDITOR OF THIS SPECIAL EDITION: Debra Nelson-Hogan<br />

MEDICINE AND HUMANITIES EDITOR: James Giordano, PhD<br />

6<br />

9<br />

FEATURES<br />

16<br />

22<br />

32<br />

40<br />

50<br />

59<br />

63<br />

68<br />

72<br />

74<br />

82<br />

Editor’s Corner<br />

By Lennie Duensing and Debra Nelson-Hogan<br />

Dolor, Morbus, Patiens: Maldynia, Pain as Illness and Suffering<br />

By James Giordano, PhD<br />

RSDSA: Expanding Research,<br />

Education, and Awareness of CRPS<br />

By James W. Broatch, MSW, RSDSA Executive Director<br />

PEOPLE WITH CRPS: THEIR STORIES AND<br />

ACCOMPLISHMENTS 23 Stephen Spagnoli • 24 Wilson Hulley<br />

25 Barbara Schaffer • 26 Lisa Delia• 27 Sharon Weiner<br />

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome:<br />

New Hope After a Decade of Dispelling Myths<br />

By Bradley S. Galer, MD<br />

Exploring Psychosocial Issues in CRPS<br />

An Interview Edward C. Covington, MD<br />

When Children Hurt Too Much: Diagnosis and<br />

Treatment of Amplified Musculoskeletal Pain<br />

By David D. Sherry, MD<br />

EMERGING TREATMENT AND DIAGNOSIS<br />

Neuroimmunologic Approaches to Emerging<br />

and Potential Therapies for CRPS<br />

By Donald C. Manning, MD, PhD<br />

Ziconotide: Promising New Treatment for<br />

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)<br />

By Lynn R. Webster, MD, and Keri L. Fakata, PharmD<br />

New Rechargeable Spinal Cord Stimulator Systems<br />

Offer Advantages in CRPS Treatment<br />

By Joshua P. Prager, MD, MS<br />

The Use of Thermography in the<br />

Diagnosis of CRPS: A Physicians’ Opinion<br />

By Philip Getson, DO<br />

IN CONCLUSION<br />

A Theory of Suffering<br />

Peter A. Moskovitz, MD<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

82 Academy News • 84 Classified Advertisements • 85 Directory<br />

On the Cover: Allodynia by Stephen Spagnoli. This painting in iodine and acrylics is<br />

an actual imprint of the artist’s body.<br />

Academy Board of Directors<br />

President<br />

Paula L. Gilchrist, LPT, DPM<br />

Secretary<br />

Barbara Lum, BS<br />

Treasurer<br />

Carl H. McNeely, APRN, PNP<br />

Co-Chairs, Board of Advisors<br />

Rick Marinelli, ND, MAcOM, LAc<br />

Gerald Q. Greenfield Jr., MD<br />

Director-at-Large<br />

Christopher Brown, DDS, MPS<br />

Academy Staff<br />

Executive Director<br />

Kathryn A. Padgett, PhD<br />

Deputy Executive Director<br />

Marsha Stanton, MS, RN<br />

Director of Education<br />

Terry Finigian<br />

Education Administrator<br />

Lois Baker<br />

Director of Pain Program<br />

Accreditation and Outcomes<br />

Measurement<br />

Alexandra Campbell, PhD<br />

Director of Communications<br />

and Advocacy<br />

Lennie Duensing, MEd<br />

Administrative Assistant<br />

Mari Fairhurst<br />

Director of Publications<br />

Carol Harper, MA<br />

Director of Sales<br />

Jillian Manley<br />

Sales Representative<br />

Rosemary LeMay<br />

General Membership Coordinator<br />

Marcella Mateo<br />

Credentialing, Office Manager<br />

Joy McCurry<br />

Chief Financial Officer<br />

Connie Mulalley<br />

Academy Consultants<br />

Research Consultant<br />

Edward E. Duensing, MLS<br />

Copy Editor<br />

Nan Newell<br />

The Pain Practitioner is published by the American<br />

Academy of Pain Management, 13947 Mono<br />

Way, Ste. A, Sonora, CA 95370, Phone<br />

209-533-9 7 4 4 , F a x 2 0 9 - 5 3 3 - 9 7 5 0 , and<br />

Email: aapm@aapainmanage.org, website:<br />

www. aapainmanage.org. Copyright 2006<br />

American Academy of Pain Management. All<br />

rights reserved. Send correspondance to Lennie<br />

Duensing, MEd, at lduensing@yahoo. com.<br />

Contact Jillian Manley at 209-533-9744<br />

regarding advertising opportunities, media kits,<br />

and prices.<br />

The Pain Practitioner is published by the<br />

American Academy of Pain Management solely<br />

for the purpose of education. All rights are<br />

reserved by the Academy to accept, reject, or<br />

modify any submission for publication. The<br />

opinions stated in the enclosed printed<br />

materials are those of the authors and do not<br />

necessarily represent the opinions of the<br />

Academy or individual members. The Academy<br />

does not give guarantees or any other<br />

representation that the printed material<br />

contained herein is valid, reliable, or accurate.<br />

The American Academy of Pain Management<br />

does not assume any responsibility for injury<br />

arising from any use or misuse of the printed<br />

material contained herein. The printed material<br />

contained herein is assumed to be from reliable<br />

sources, and there is no implication that they<br />

represent the only, or best, methodologies or<br />

procedures for the pain condition discussed. It<br />

is incumbent upon the reader to verify the<br />

accuracy of any diagnosis and drug dosage<br />

information contained herein, and to make<br />

modifications as new information arises.<br />

All rights are reserved by the Academy to<br />

accept, reject, or modify any advertisement<br />

submitted for publication. It is the policy of the<br />

Academy to not endorse products. Any<br />

advertising herein may not be construed as an<br />

endorsement, either expresed or implied, of a<br />

product or service.<br />

4 | T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

EDITORS’ CORNER | COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME<br />

LENNIE DUENSING<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

CRPS Special Edition<br />

BY LENNIE DUENSING, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF<br />

AND DEBRA NELSON-HOGAN, CO-EDITOR, SPECIAL CRPS EDITION<br />

DEBRA NELSON-HOGAN<br />

Co-Editor<br />

“Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a perplexing<br />

condition that has been relatively ignored and misunderstood<br />

by the medical community because it is so unusual.”<br />

— BRADLEY S. GALER, MD<br />

THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PAIN MANAGEMENT AND<br />

THE REFLEX SYMPATHETIC DYSTROPHY SYNDROME<br />

ASSOCIATION have joined together to produce this<br />

special spring edition of The Pain Practitioner. Entitled,<br />

“CRPS: Grappling with the Mysteries,” the issue explores<br />

the most current thinking about Complex Regional Pain<br />

Syndrome (CRPS) from a variety of perspectives.<br />

Why an Issue on CRPS?<br />

WE TOOK ON THIS JOINT PROJECT because CRPS is a condition<br />

that creates a host of treatment nightmares for clinicians.<br />

Unfortunately, most healthcare professionals lack education<br />

about the condition and often delay diagnosis and treatment.<br />

Worse yet, some healthcare professionals and insurance<br />

providers still don’t believe the syndrome exists. The McGill<br />

Pain Scale, however, ranks CRPS pain higher than cancer pain,<br />

and for many of those living with CRPS, the constant and<br />

burning pain creates nothing short of a living hell. This is well<br />

illustrated in the paintings of CRPS sufferer Stephen Spagnoli,<br />

which appear throughout this issue. (See story on page 22 )<br />

In this Issue<br />

James Giordano, PhD, the publication’s new Medicine and<br />

Humanities Editor, opens the issue with a commentary entitled,<br />

“Dolor, Morbus, Patiens: Maldynia, Pain as Illness and<br />

Suffering.” Giordano addresses the need to comprehend the<br />

complexity of pain and suffering, and says that, “… scientific<br />

and humanistic inquiry is fundamental to the provision of<br />

technically right and morally good care.”<br />

James W. Broatch, MSW, RSDSA Executive Director, in<br />

“RSDSA: Expanding Research, Education, and Awareness of<br />

CRPS,” describes that organization’s work discusses the<br />

particular challenges that people who have CRPS face, and how<br />

the 22-year-old organization meets them. There is also a brief<br />

overview of the new third edition CRPS Clinical Practice<br />

Guidelines.<br />

In his article, “Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: New Hope<br />

After a Decade of Dispelling Myths,” Bradley S. Galer, MD,<br />

addresses many facets of this generally misunderstood and<br />

confusing syndrome. Galer looks at the causes of CRPS and<br />

highlights some of the advances made in recent years that have<br />

led to a better understanding of this syndrome, dispels myths<br />

and misconceptions, and describes treatments.<br />

Edward C. Covington, MD, Director of the Chronic Pain<br />

Rehabilitation Program at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation,<br />

discusses the psycho-social issues in CRPS. Covington addresses<br />

CRPS in relation to personality and cognition, the value of<br />

6 | T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

WORKERS’ COMPENSATION PRESCRIPTIONS<br />

WHAT GOOD IS A PRESCRIPTION<br />

IF YOUR PATIENT CAN’T<br />

PAY FOR IT OR IT’S DENIED<br />

BY THE CARRIER?<br />

ENSURE THAT YOUR INJURED WORKER PATIENTS GET THE<br />

MEDICATION THEY NEED...<br />

Talk to Injured Workers Pharmacy. As a trusted resource, we are an independent<br />

advocate for the injured worker, their physician and attorney. As the experts in<br />

workers’ compensation claims, we manage everything: detailed recordkeeping,<br />

claims issues, complete pharmacy services including custom compounding and<br />

medical equipment with convenient delivery to your patient’s home. All at no<br />

charge – to you or your patient.<br />

One call to us can take away the financial obstacles that threaten your patient’s<br />

recovery and relieve your staff of administrative burdens. We make sure your<br />

patient receives the prescriptions you write, right from the start.<br />

Enroll Your<br />

Patients Today:<br />

888-321-7945<br />

www.iwpharmacy.com<br />

A PROVEN ADVOCATE FOR THE RIGHTS OF A LL INJURED WORKERS. ENSURE<br />

ESSENTIAL MEDICAL CARE IS PROVIDED BY MAKING US PART OF YOUR TEAM TODAY.

EDITORS’ CORNER | COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME<br />

exercise and activity, and various psychological treatments.<br />

Covington says, “There are people with CRPS who have<br />

managed to transcend it and have a life. For others, it’s less the<br />

case that they have CRPS than that ‘CRPS has them.’”<br />

Pediatric CRPS can be an entirely different syndrome. In his<br />

article, “When Children Hurt too Much: Diagnosis and<br />

Treatment of Amplified Musculoskeletal Pain.” David D.<br />

Sherry, MD, discusses amplified musculoskeletal pain and<br />

describes the epidemiology, etiology, clinical manifestations,<br />

diagnosis, and treatment, and outcomes of these conditions<br />

based on his experience. He says that with the treatment he<br />

recommends, “Most children do well.”<br />

The magazine also includes a special section with articles<br />

focusing on emerging treatments for CRPS (both<br />

pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches). An<br />

article by Joshua P. Prager, MD, explores the use of spinal cord<br />

stimulation for people with CRPS. Lynn R. Webster, MD, and<br />

Keri L. Fakata, PharmD, discuss ziconotide, a new, nonnarcotic<br />

treatment delivered via an intrathecal pump that is a<br />

treatment option for CRPS patients. Donald C. Manning,<br />

MD, PhD, describes other emerging treatments, and Philip<br />

Getson, MD, gives a brief summary of thermography in the<br />

diagnosis of CRPS.<br />

The section, People with CRPS: Their Stories and<br />

Accomplishments, presents stories about five people with CRPS,<br />

who in spite of their pain, are working in a variety of ways to<br />

support others with the condition.<br />

The issue concludes with a compelling and thoughtful<br />

commentary by Peter A. Moskovitz, MD, called “A Theory of<br />

Suffering.” Moskowitz puts forth a six-part theory that explores<br />

the nature of suffering. He concludes by saying, “The capacity<br />

for suffering is the precursor to natural morality. I stand at the end<br />

of a long line of scientists and ethicists, some cited here, to repeat<br />

that empathy and the understanding of suffering, however elusive<br />

they may be, are the moral obligation of the pain practitioner.…<br />

The treatment of diseases and injuries includes the treatment of<br />

pain. The treatment of pain is all about suffering.”<br />

Debra Nelson Hogan is a communications consultant for RSDSA.<br />

Adding a New Dimension<br />

to The Pain Practitioner<br />

THE ACADEMY WELCOMES JAMES GIORDANO, PHD,<br />

AS MEDICINE AND HUMANITIES EDITOR<br />

THROUGH THE PAIN PRACTITIONER, the American Academy<br />

of Pain Management has provided clinicians with practical<br />

information about pain management and the latest trends in<br />

the field. Now, we are taking the publication a step further.<br />

Starting with this issue, we will be looking at pain, not only<br />

from scientific and medical perspectives, but from the perspective<br />

of the humanities as well—a perspective that hopefully<br />

will give us a greater understanding of the experience of pain,<br />

and how it expressed by those who suffer with it.<br />

To this end, the Academy is pleased to welcome James<br />

Giordano, PhD, as Medicine and Humanities Editor. In this<br />

role, Dr. Giordano will write provide editorial input and write<br />

commentary related the theme of the issue.<br />

“My hope is that we emerge from this Decade of Pain<br />

Control and Research with knowledge and understanding that<br />

advances our epistemology of pain, and in so doing, reconcile<br />

science, medicine and the humanities.” Dr. Giordano says.<br />

“My goal as Medicine and Humanities Editor of The Pain<br />

Practitioner is to create a forum for the provision and<br />

exchange of these ideas—a<br />

forum in which those who<br />

treat people with pain are<br />

empowered by the knowledge<br />

that can only be provided<br />

through a lens that<br />

brings together the<br />

pragmatic sharpness of biomedicine<br />

and the sentient<br />

focus of the humanities.” JAMES GIORDANO, PhD<br />

Dr. Giordano’s ongoing research focuses on the neuroscience<br />

and neurophilosphy of pain, agent-based virtue ethics<br />

in pain research and practice, and neuroethics. He is currently<br />

a Scholar in Residence at the Center for Clinical Bioethics,<br />

Georgetown University Medical Center; a Visiting Scholar at<br />

the Center for Ethics, Dartmouth Medical School; a Fellow<br />

of the John P. McGovern MD Center for Health, Humanities<br />

and the Human Spirit, University of Texas Health Sciences<br />

Center; and, an invited lecturer of the Roundtable in Arts and<br />

Sciences, Oxford University, UK. He is the author of over 55<br />

peer-reviewed papers and three books addressing the neuroscience<br />

of pain, medical philosophy, and bioethics. He is<br />

the bioethics section editor of the American Journal of Pain<br />

Management, editor of the Journal of Practical Pain Management,<br />

and neuroscience editor of the Pain Physician Journal.<br />

8 | T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

COMMENTARY | GIORDANO<br />

COMMENTARY:<br />

Dolor, Morbus, Patiens:<br />

Maldynia, Pain as<br />

Illness and Suffering<br />

BY JAMES GIORDANO, PhD, MEDICINE AND HUMANITIES EDITOR<br />

AS THE MEDICINE AND HUMANITIES EDITOR for<br />

The Pain Practitioner, I am grateful for the<br />

opportunity to write a commentary on the<br />

papers appearing in this issue on complex<br />

regional pain syndrome (CRPS).<br />

TOGETHER, THESE ARTICLES address this frequently misunderstood<br />

syndrome, convey how an expanding epistemology has<br />

generated enhanced understanding of the mechanistic basis and<br />

existential impact of pain as a complexity-based systems event,<br />

and present the need to develop diagnostic and therapeutic<br />

approaches that reflect this progressive knowledge.<br />

The basic and clinical sciences, humanities, and the<br />

experiential narratives of patients all contribute essential lenses<br />

through which we can examine and de-mystify the enigma<br />

of persistent pain.<br />

I believe that how we come to know about pain<br />

is equally important as, and provides a pediment for, what<br />

we know about pain. It is only through the combination of<br />

distinct domains of knowledge that we can both comprehend<br />

pain as a dysfunction of the dynamical, nonlinear adaptability<br />

of the nervous system, and at the same time apprehend the<br />

manifestations of these changes within the networked-hierarchy<br />

of interacting systems that is the patient as person. 1 Thus,<br />

the study of pain conjoins neuroscience to the burgeoning<br />

discourse of neurophilosophy and, in so doing, may reconcile<br />

issues in the dialectic surrounding the concepts of disease—<br />

illness, brain-mind, and ethical dimensions of care.<br />

Pain as a Spectral Disorder<br />

I POSIT THAT PAIN CAN BE CONSIDERED TO BE A SPECTRAL<br />

DISORDER—one that ranges from a symptom of organic insult<br />

or trauma, to durable, more global pathologic changes occurring<br />

at multiple levels of the nervous system, ultimately affecting<br />

the substrates that are involved in and/or elicit behavior,<br />

emotion, and cognition of the (internal and external) environment<br />

and, thus, some form of the definable “self.” 2<br />

I maintain that with progression across this spectrum, the<br />

disease process of pain increasingly becomes the phenomenal<br />

illness of pain. Classification and diagnoses must acknowledge<br />

pain as disease and manifest illness, recognizing, too, that the<br />

disease process may be durable and immutable (1).<br />

The arbitrary temporal classifications that rested upon the<br />

acuteness or chronicity of pain did little to define the etiologic<br />

and pathophysiologic processes that may cause or perpetuate<br />

the disorder. Hence, these criteria have been replaced by nosologic<br />

distinctions (e.g., nociceptive vs. neuropathic; Type I, II,<br />

III) that have sought to characterize pain according to the<br />

inherent neurological mechanisms. Woolf, Borsook, and<br />

Koltzenburg (2) have recently expanded this schema into an<br />

elegant algorithmic model that thoroughly accounts for stimulus<br />

dependency and neural basis, enabling both mechanistic<br />

identification of types of pain and proof of concept evidenced<br />

in clinical syndrome(s). Certainly, this algorithm can be considered<br />

to be situated along, and/or be representative of, the pain<br />

spectrum, as I have proposed. Yet, the “meaning” and manifestations<br />

of these types of pain still remain implicit in, if not altogether<br />

absent from, the algorithm of Woolf et al. Almost a<br />

decade ago, Lippe (3) proposed the use of the term eudynia to<br />

represent physiologically “normal” or nociceptive pain, and<br />

maldynia to be “abnormal” pain arising from neuropathic<br />

processes. These terms have become increasingly popular, but I<br />

feel that when used alone, they do little to define what “normality”<br />

and “abnormality” actually mean. Similarly, the sole use<br />

of the categorization scheme of Woolf and colleagues is some-<br />

1 These are concepts that are inherent to, and derived from, complexity theory.<br />

I feel that the use of a complexity-based model of pain is important to fully<br />

reconcile the notions of disease and illness, and to fit these within a more<br />

encompassing framework. For a review of complexity theory and its applicability<br />

to neuroscience and medicine, see: Kelso, JS. Dynamic Patterns: The<br />

Self-Organization of the Brain and Behavior, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1995;<br />

Waldrop MM. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and<br />

Chaos, NY, Touchstone Books, 1992; Dayan P, Abbott LF. Theoretical Neuroscience:<br />

Computational and Mathematical Modeling of Neural Systems. Cambridge,<br />

MIT Press, 2001; and for a straightforward overview, see: Sarder Z,<br />

Abrams I. Introducing Chaos, Cambridge (UK), Icon Books, 2003.<br />

T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | V O L U M E 16 , N U M B E R 1 | 9

COMMENTARY | GIORDANO<br />

Comprehending the complexity of …<br />

suffering involves both scientific and<br />

humanistic inquiry and is fundamental<br />

to the provision of technically right<br />

and morally good care.<br />

what sterile and does not depict the potentiality of effects<br />

elicited by a particular type of pain. However, if framed as<br />

domains within the spectrum of pain, these classifications<br />

impart insight to mechanism(s), manifestation(s), and broader<br />

existential meaning.<br />

Maldynia: The Illness of Pain as Suffering<br />

I PROPOSE THAT MALDYNIA be reconsidered to be the multidimensional<br />

constellation of symptoms and signs that represent the syndrome<br />

of persistent pain as phenomenal illness. Thus, by its nature,<br />

maldynia (irrespective of initiating cause and/or constituent<br />

mechanisms) produces, and results from, functional and perhaps<br />

structurally maladaptive changes in the nervous system that<br />

evoke, and are reciprocally affected by, alterations in cognition,<br />

emotion, and behavior. In this way, maldynia is both the conscious<br />

state of pain and a consciousness of pain as a condition of<br />

the internal domain of the lived body and existential disattunement<br />

of the life world. 3 This definition compels a more thorough<br />

consideration of the philosophical and pragmatic basis of pain<br />

medicine, for if maldynia is the illness of pain experienced as suffering,<br />

then the ethical obligations of the pain practitioner are<br />

soundly-based upon an objective knowledge and subjective affirmation<br />

that a patient’s pain and suffering are genuine. 4<br />

Moskovitz describes CRPS as the quintessential maldynic<br />

syndrome. This is well illustrated by Galer and Covington, who<br />

note how multiple biological and psychosocial factors contribute<br />

to, and are affected by, CRPS. The authors take steps to<br />

reveal CRPS not as an unsolvable mystery or specious myth,<br />

but as a complicated clinical problem that is explicable and<br />

treatable. But complicated problems are rarely resolved through<br />

simple means, and the diagnosis and treatment of CRPS<br />

require an insightful, innovative approach that is wholly focal to<br />

the varying pathologic bases and unique, needs of each patient.<br />

The cornerstone of this approach is accurate diagnosis, (4, 5)<br />

and Sherry addresses the differential diagnosis of persistent<br />

musculoskeletal pain in adolescents as an example of how precise,<br />

timely assessment is essential to establishing and implementing<br />

what should be done to most effectively treat a particular<br />

patient with a specific pain disorder. Diagnosis is built<br />

from generalized and specifically contextual knowledge, and<br />

Getson examines thermography as a novel technology and technique,<br />

that, when utilized within an expanded objective and<br />

subjective diagnostic framework, may afford improved evaluative<br />

acumen, thereby determining the appropriate type and ultimate<br />

trajectory of subsequent care. Manning, Webster, and<br />

Fakata, as well as Prager each discuss this care, and their work<br />

emphasizes the importance and viability of rational pharmacology<br />

and new technologies, in an approach that reflects understanding<br />

of the contributory neuropathic mechanism(s), as well<br />

as the relational importance of how these mechanisms are<br />

expressed in the patient.<br />

I maintain that this latter point is particularly critical to<br />

treatment. While there is considerable similarity in the underlying<br />

neural mechanisms of CRPS, their manifestations can be<br />

widely different, based upon the compound predispositions of<br />

each person. The clinician must take this into account when<br />

considering the prudential question of what should be done to<br />

best meet the medical needs of a given patient at a particular<br />

point in the disease-illness continuum (4, 6, 7). Such “customization”<br />

of care allows for evaluation and therapeutics based<br />

upon multiple levels and domains of evidence and is instrumental<br />

in providing the right treatment(s) for the right reason(s) (8,<br />

9). Instead of being inappropriately wedded to a singularly disease-based,<br />

curative model, this approach embraces a larger,<br />

more integrative paradigm, (10) that I feel acknowledges and<br />

communicates to the patient that while cure may not be possible,<br />

effective, ethical care is both achievable and obligatory.<br />

Toward a Neurophilosophy of Pain<br />

GIVEN THE NOTION THAT:<br />

[1] maldynia induces functional and structural changes in<br />

the neurological axis from periphery to brain;<br />

[2] distinct regions in the brain are responsible for the conditions<br />

and awareness of discriminable consciousness (e.g.,<br />

the cingulate gyrus, parietal, prefrontal, and operculoinsular<br />

cortex); and<br />

[3] maldynia-induced changes in these brain regions are capable<br />

of evoking alteration of the sensed internal state that is consciousness,<br />

it becomes clear that maldynia (i.e., pain as suf-<br />

2 There is considerable discussion in the neural sciences (i.e., neurobiology,<br />

cognitive psychology, [neuro]philosophy) regarding the nature or existence<br />

of the “self.” To gain insight into recent perspectives of some of the leading<br />

scholars in this discourse, see: Blackmore S. Conversations on Consciousness:<br />

What the Best Minds Think About the Brain, Free Will, and What It<br />

Means to Be Human. Cambridge (UK), Oxford University Press, 2005.<br />

3 I base this upon the model of levels of conscious processing, first detailed<br />

in psychological terms by Ray Jackendoff (Consciousness and the Computational<br />

Mind, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1990); and expanded by Jesse Prinz<br />

(Furnishing the Mind: Concepts and Their Perceptual Basis, Cambridge, MIT<br />

Press, 2004) to include neural substrates. I feel that this model fits well<br />

within a complexity-based paradigm, and bridges neural mechanisms with<br />

phenomenal experience(s). For further discussion of the phenomenological<br />

approach to illness and pain, see: Gadamer HG. The Enigma of Health. Stanford,<br />

Stanford University Press, 1996; Husserl E. Ideas: General Introduction<br />

to a Pure Phenomenology. NY, Collier, 1962; Svenaeus F. The Hermeneutics of<br />

Medicine and the Phenomenology of Health. Dordrecht, Kluwer, 2000; and<br />

Zaner R. The Problem of Embodiment: Some Contributions to a Phenomenology<br />

of the Body. The Hague, Nijhoff, 1964.<br />

4 Suffering is an extensive topic of study. One of the leading scholars in this<br />

field is Eric Cassell. For an overview of his work specific to a discussion of<br />

suffering and the ethical obligations in caring for those who suffer, see: Cassell<br />

E. The Healer’s Art, NY, Lippincott, 1976, and, Cassell E. The Nature of<br />

Suffering, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1991.<br />

10 | T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

fering) may be a disorder of the brain that directly or indirectly<br />

effects a condition of the expressed “mind.”<br />

In this context, Moskovitz’s work becomes particularly<br />

noteworthy. Based upon his clinical experience and the current<br />

body of experimental and philosophical literature, Moskovitz<br />

has developed a theory that localizes suffering to the cingulate<br />

gyrus and adjacent limbic forebrain. Certainly, there is evidence<br />

from recent neuroimaging studies to support the neuroanatomical<br />

basis of his theory, at least in part (11, 12, 13). An interesting<br />

dimension of Moskovitz’s thesis is its solidification of<br />

suffering as a brain event that is evoked by hierarchical mechanisms<br />

of pain, yet allows (indeed, encourages) a philosophical<br />

interpretation of whether suffering represents a biological effect<br />

of the brain state (i.e., a “physical kind”), or is a distinct property<br />

(i.e., a “mental kind”) that exists as some nonmaterial construct<br />

of consciousness. 5 Regardless it is knowable in its entirety<br />

only to the sufferer: even if there were some way to completely<br />

transpose the pattern of cerebral activation from one person<br />

directly to another (e.g., from patient to clinician), the subjective<br />

experience of that identical brain activation would still differ,<br />

since the connectivities shaped by genotype and the myriad<br />

of life experiences are so widely variant (14).<br />

Thus, while Moskovitz’s theory is attractive because it establishes<br />

a physiological basis and anatomy of pain as suffering, I<br />

think that it also raises the question of whether suffering can or<br />

will be knowable through solely objective means. The authentication<br />

of suffering cannot exclusively rely on technology (4, 6,<br />

15, 16), and it is here that this thesis to instigate somewhat<br />

broader considerations. By validating suffering as a neurobiological<br />

event, Moskovitz makes it resonant with the domain of<br />

applied biology that constitutes much of the epistemological<br />

basis for contemporary medicine. Yet, given that these neurobiological<br />

substrates are in some way foundational to consciousness,<br />

he astutely states that only contextual, intersubjective knowledge<br />

can truly afford the clinician an understanding of the unique<br />

nature of a person’s suffering. I agree, for the focus of the clinical<br />

encounter is upon the patient, literally as “the one who suffers.”<br />

Comprehending the complexity of such suffering involves<br />

both scientific and humanistic inquiry and is fundamental to<br />

the provision of technically right and morally good care. I maintain<br />

that this is incontrovertible, and hope that this issue of The<br />

Pain Practitioner provides a forum to stimulate thought and discussion<br />

about the future possibilities that such care may offer. 6<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Giordano J. Bioethics and intractable pain. Practical Pain Management,<br />

2005<br />

2. Woolf CJ, Borsook D, Koltzenburg M. Mechanism-based classifications of<br />

pain and analgesic drug discovery. In: C. Boutra, R. Munglani, WK<br />

Schmidt (eds.) Pain: Current Understanding, Emerging Therapies, and<br />

Novel Approaches to Drug Discovery. NY, Marcel Dekker, 2003, pp. 1-8.<br />

3. Lippe P. An apologia in defense of pain medicine. Clin. J. Pain. 1998, 14<br />

(3): 189-190.<br />

4. Giordano J. Toward a core philosophy and virtue-based ethics of pain<br />

medicine. The Pain Practitioner, 2005, 15(2): 59-66.<br />

5. Sadler JZ. Diagnosis/anti-diagnosis. In: J. Radden (ed.) The Philosophy of<br />

Psychiatry: A Companion. NY, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp. 163-179.<br />

6. Giordano J. Moral agency in pain medicine: Philosophy, practice and<br />

virtue. Pain Physician, 2006, 9: 71-76.<br />

7. Pellegrino ED. For the Patient’s Good: The Restoration of Beneficence in<br />

Health Care. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1987.<br />

8. Turk DC. Customizing treatment for chronic pain patients: who, what, and<br />

why? Clin. J. Pain, 1990, 6: 255-270.<br />

9. Giordano J. Pain research: Can paradigmatic revision bridge the needs of<br />

medicine, science and ethics? Pain Physician, 2004, 7: 459-463.<br />

10. Bonakdar R. Integrative pain management: A look at a new paradigm.<br />

The Pain Practitioner, 2005, 15 (1): 15-18.<br />

11. Bromm B. Brain images of pain. News Physiol. Sci. 2001, 16: 244-249.<br />

12. Apkarian AV, Thomas PS, Krauss BR, Szeverenyi NM. Prefrontal cortical<br />

hyperactivity in patients with sympathetically mediated chronic pain.<br />

Neurosci. Lett., 2001, 311: 193-197.<br />

13. Bingel U, Quante M, Knab R, Bromm B, Weiller C, Buchel C. Subcortical<br />

structures involved in pain processing: Evidence from single-trial fMRI.<br />

Pain, 2002, 99: 313-321.<br />

14. Coghill RC, McHaffe JG, Yen Y-F. Neural correlates of inter-individual differences<br />

in the subjective experience of pain. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 2003,<br />

100 (14): 8538-8542.<br />

15. Reiser SJ. Medicine and the Reign of Technology. Cambridge, Cambridge<br />

University Press, 1978.<br />

16. Sullivan M. Exaggerated pain behavior: By what standard? Clin. J. Pain,<br />

2004, 20 (6): 433-439.<br />

5 The definitions of “kind” are used here in the philosophical sense to mean<br />

a group of things or occurrences that have inherent qualities in common.<br />

Thus, a “physical kind” refers to those things that are directly arising from,<br />

and belonging to, a set of purely physiological events. In contrast, a “mental<br />

kind” refers to those things that may have arisen from something physical,<br />

but have an inherent and unique set of characteristics that separate<br />

them from those things that are physiological. The latter characterization<br />

formalizes that mental processes are different from physiological ones. This<br />

distinction allows for the fact that consciousness may be emergent from the<br />

physiological processes of neurons, but also gives substance to the idea that<br />

conscious processes are in some way “more” than the result of the physiology<br />

that may have produced them.<br />

This speaks to the major “schools,” or orientations in contemporary science<br />

and philosophy of mind, that range from the viewpoint that any mental<br />

event is wholly reducible to a brain event (e.g., materialism and related<br />

orientations of theoretically reductive physicalism), to some middle-ground<br />

positions that allow that brain events produce mind events, but that mind<br />

events have more expansive characteristics or are greater than the sum of<br />

the events which produced them (e.g., nonreductive physicalism, property<br />

dualism, emergence, complementarity) and at the other extreme, the idea<br />

that there is a discernible mental field that occurs within the brain, but is<br />

irreducible, and perhaps unknowable (e.g., strict dualism). There are several<br />

issues in neuroethics that are related to the implications of these distinctions<br />

(e.g., the nature of the “self,” self-determinism, free will, etc.).<br />

The philosopher Colin McGinn claims that our study of the mind is at a<br />

point of “cognitive closure,” given the inherent limitations of the contemporary<br />

human brain. Instead, I prefer to think, optimistically, that we are on a<br />

path of extended contemplation that allows us to gain ongoing insight from<br />

an ever-increasing knowledge base achieved through widening collaboration<br />

within, and between, multiple disciplines. Again, it is beyond the scope of<br />

this paper to address the nature of consciousness, but one can see how this<br />

discussion would nonetheless be important to the study of pain, suffering,<br />

and the ethics of science and medicine.<br />

6 Obviously, the extent of the topic of CRPS cannot be completely or fully<br />

addressed in a volume such as this. For a thorough summary of mechanistic,<br />

diagnostic, and therapeutic approaches to CRPS, see: Wilson PR, Stanton-<br />

Hicks M, Harden RN (eds.) CRPS: Current Diagnosis and Therapy. Seattle,<br />

IASP Press, 2005.<br />

T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | V O L U M E 16 , N U M B E R 1 | 11

FEATURE | BROATCH<br />

RSDSA: Expanding Research,<br />

Education, and Awareness of CRPS<br />

BY JAMES W. BROATCH, MSW, RSDSA EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR<br />

SCIENTISTS AND CLINICIANS ARE STILL BAFFLED by this<br />

little-known, poorly understood collection of signs and<br />

symptoms of CRPS—what causes it, why it develops<br />

in one person and not in another with the same injury,<br />

why it occurs in more females than males, and why<br />

children and teens with this syndrome generally get<br />

better while most adults (80 percent in one prospective<br />

study) cannot resume prior activities (1).<br />

The <strong>Reflex</strong> <strong>Sympathetic</strong> <strong>Dystrophy</strong> Syndrome Association<br />

(RSDSA) deals with issues like these every day. Founded in<br />

1984 to raise money for research, over the years, our mission<br />

has broadened to include awareness, education, patient support,<br />

legislative issues, and the creation of a CRPS patient<br />

database. Based in Milford, Connecticut, RSDSA has two fulltime<br />

employees and is guided by a talented 10-member board<br />

of directors (four of whom have CRPS). Our Scientific Advisory<br />

Committee is led by R. Norman Harden, MD, and<br />

Srinivasa N. Raja, MD, and is comprised of some of the key<br />

thought leaders on CRPS who serve as consults on medical,<br />

treatment, and research issues. RSDSA has grown into a<br />

national, nonprofit organization with an annual revenue is<br />

over $600,000, 90 percent of which is spent on research and<br />

educational programming.<br />

Research<br />

RSDSA is committed to encouraging research to discover the<br />

cause(s) and cure(s) of CRPS. Why? Because medical professionals<br />

and the public are still largely unaware of this intensely<br />

painful and potentially debilitating syndrome. For example, a<br />

1999 epidemiology study published in PAIN reported that the<br />

mean number of different physicians who evaluated a CRPS<br />

patient prior to being seen at a pain center was 4.8 (2). Then in<br />

2005, an Internet-based survey of 1,362 people with CRPS<br />

(conducted by Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and funded<br />

by RSDSA) found that 56 percent of the respondents saw more<br />

than four physicians prior to being diagnosed with CRPS-not<br />

much of an improvement!<br />

Also, the reality is: you can’t cure what you don’t understand!<br />

Peter Moskowitz, MD, a member of the RSDSA board of<br />

directors, explains, “Science helps us learn new things, and there is<br />

much we want to know about CRPS. The best science not only<br />

helps us know about difficult subjects—and CRPS is a very difficult<br />

subject—it also tells us how we know what we know and<br />

informs our understanding of the disease process and its treatment.”<br />

It is for these reasons that we fund at least two research<br />

grants (up to $50,000 each) every year. Since 1992, RSDSA has<br />

funded $732,665 in fellowships and research grants. Recent<br />

RSDSA-funded grants include:<br />

❥ Treatment of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I by<br />

Nitroglycerine, A Web-Based Epidemiological Survey of CRPS-I;<br />

❥ Identification of CRPS Subtypes and Effective Treatments;<br />

❥ Changes in CSF Cytokine levels in <strong>Reflex</strong> <strong>Sympathetic</strong><br />

<strong>Dystrophy</strong>; Validation of Revised Diagnostic Criteria<br />

for CRPS/RSD; and,<br />

❥ Noninvasive Investigation of Human Brain Mechanisms<br />

Associated with the Development and Treatment of RSD.<br />

An Outcome of RSDSA Research Funding<br />

In 2004, we funded a study called Development of a rat model<br />

of CRPS-I based on partial injury to nociceptive axons. The<br />

results of this study prompted further research, which evolved<br />

into a paper written by Anne Louise Oaklander, MD, PhD,<br />

called Evidence of focal small-fiber axonal degeneration in complex<br />

regional pain syndrome-I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). This<br />

study will be published in Pain and proves that: “CRPS-I now<br />

has an identified cause takes it out of the realm of so-called<br />

‘psychosomatic illness.’ (3)”<br />

Detailed application guidelines for funding can be<br />

found on our website at: www.rsds.org<br />

Education and Awareness<br />

In order to encourage accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment,<br />

RSDSA has developed informative educational brochures<br />

with the assistance of our Scientific Advisory Committee. One<br />

of the most widely distributed is a screening tool for medical<br />

professionals—a laminated, two-sided, wallet-sized card that lists<br />

the signs and symptoms of CRPS Type I on one side and provides<br />

a pain rating scale on the other. We mailed the card along<br />

with an informative cover letter to members of the American<br />

16 | T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Physician<br />

Assistants, and the American Society of Pain Management<br />

Nursing. The letter began with the prescient sentence “A minute<br />

of your time can prevent a lifetime of suffering.” The response<br />

was enthusiastic. Many of the physicians and nurses were on<br />

medical- and nursing-school faculties and requested multiple<br />

copies for their students and fellows. RSDSA members also<br />

asked for individual copies for themselves and other family<br />

members and additional copies to distribute to medical professionals<br />

in their communities.<br />

In addition, RSDSA is publishing its third edition of<br />

evidenced-based Clinical Practice Guidelines (in press) and<br />

the RSDSA Review Digest, a compendium of articles that have<br />

appeared in the RSDSA Review on the diagnosis, treatment,<br />

and management of CRPS. Although the articles are archived<br />

on our website, 42 percent of Americans do not have access to<br />

the Internet and most medical professionals are too busy<br />

to thoroughly search our website. The Digest will be a perfect<br />

companion to the Clinical Practice Guidelines. We expect that<br />

medical professionals will also distribute the compendium to<br />

their patients with CRPS. If you would like to receive any of<br />

our free materials, please call 877-662-7737.<br />

Each year, staff and volunteers exhibit at major medical,<br />

insurance, and school nurse conventions and conferences.<br />

RSDSA believes it is vitally important for its members to attend<br />

new conferences in order to inform the attendees about our<br />

programs and educational materials, our top-notch website,<br />

research funding opportunities, ongoing CRPS clinical trials,<br />

and to discuss with medical professionals how we can work<br />

with them to help their patients and improve their practices.<br />

Shefali Agarwal, MPH, Srinivasa Raja, MD, both from Johns Hopkins School of<br />

Medicine and Bradley Galer, MD, RSDSA board member, discuss the results of an<br />

Internet-based epidemiological study funded by RSDSA.<br />

Patient Support<br />

At RSDSA, we are acutely aware of the devastation caused by<br />

the pain of CRPS. People become disabled and marriages fail.<br />

Families break part and lives are financially ruined. People<br />

become socially isolated and housebound. In our 2005 Internet<br />

Survey, 47 percent of the respondents reported that they had<br />

considered suicide and 15 percent of this group had tried.<br />

Although there is no hard data on the number of CRPS-related<br />

suicides, the donations section of our newsletter includes several<br />

gifts made in memory of individuals who, more often than not,<br />

have taken their own lives. It is chilling.<br />

For this reason, although we do not offer formal patient<br />

services, I do talk to those people who call<br />

or send email, as does my assistant, Gayle<br />

Bonavita, and several of our board members<br />

who have CRPS.<br />

CRPS Education Bills<br />

Through grass-roots initiatives, we have<br />

helped people with CRPS in their efforts<br />

to get CRPS Awareness legislation<br />

passed in Delaware, New York, and Pennsylvania;<br />

similar legislation has been or<br />

will be introduced in New Jersey, Illinois,<br />

Oregon, Michigan, and California. The<br />

legislation mandates that a state’s<br />

Department of Health conduct medical<br />

professional and public education programs<br />

to encourage earlier detection and<br />

appropriate treatment of CRPS.<br />

Jim Broatch talks to attendees at the Academy’s annual meeting in San Diego.<br />

T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | V O L U M E 16 , N U M B E R 1 | 17

FEATURE | BROATCH<br />

We are acutely aware of the devastation caused by the pain of CRPS.<br />

People become disabled and marriages fail. Families break part and lives<br />

are financially ruined. People become socially isolated and housebound.<br />

CRPS, Social Security, Workers’<br />

Compensation, and the Insurance Industry<br />

Although it is a challenge for most people who apply for Social<br />

Security Disability benefits, individuals with CRPS are hampered<br />

by the lack of knowledge and understanding of the syndrome<br />

itself. In 1999, RSDSA was instrumental in convincing<br />

the Social Security Administration to issue a special ruling on<br />

how to adjudicate CRPS claims. We continue to receive letters<br />

RSDSA Publications<br />

and email from members<br />

who have used<br />

our information to get<br />

their claims approved.<br />

Injured employees<br />

with CRPS do not fare<br />

well in the Workers’<br />

Compensation (WC)<br />

program. Of the 1,362<br />

people who completed<br />

the web-based survey,<br />

41% reported being<br />

injured at work; however,<br />

only a few of<br />

them obtained workers’<br />

compensation benefits.<br />

Too often, the<br />

relationship between<br />

an injured worker and<br />

the WC insurance carrier<br />

erupts into a war.<br />

Treatment is frequently<br />

delayed and denied.<br />

In 2005, RSDSA<br />

exhibited at the conferences<br />

of two major workers’ compensation groups, the<br />

Risk and Insurance Management Society and Case Management<br />

Society of America. We view these conferences as opportunities<br />

to reach out to case managers and risk managers,<br />

some of whom still view CRPS as a nebulous, expensive,<br />

and frequently fraudulent claim. We launched a special newsletter,<br />

Working Together, Ensuring a Brighter Future, at these conferences.<br />

Our goal is to develop a mutually beneficial<br />

relationship. We will distribute our new Clinical Practice Guidelines<br />

to the insurers to encourage early intervention and appropriate<br />

treatment, enabling individuals with CRPS to recover<br />

and return to work.<br />

RSDSA publishes several free brochures to help people with CRPS/RSD, their families, and their healthcare<br />

providers. Please call RSDSA at 877-662-7737 to order copies.<br />

In Pain, Out of Work, and Can’t Pay the Bills, a resource directory, contains information on government programs, patient<br />

assistance programs, insurance, community and faith-based sources of help, resources for veterans, and much more.<br />

Recognizing, Understanding, and Treating CRPS/RSD is a quick overview of the syndrome, its telltale signs and symptoms,<br />

and treatment ideas. It is particularly valuable for those people who are newly diagnosed and their families.<br />

Helping Children with RSD Succeed in School is a practical guide for parents, teachers, school nurses, and administrators<br />

on accommodating the school environment for children and adolescents who have CRPS/RSD.<br />

Treating Complex Regional Pain Syndrome/<strong>Reflex</strong> <strong>Sympathetic</strong> <strong>Dystrophy</strong> Syndrome, A Guide for Therapy contains<br />

information on evaluation of CRPS/RSD for functional rehabilitation, treatment protocols, and treatment progression.<br />

CRPS/RSD and Sports Injuries: Prevention is the Name of the Game addresses the risk that athletes have of developing<br />

the syndrome. New research also links the development of CRPS to some of the surgeries that have traditionally helped<br />

sports injuries. This brochure is a must-read for athletes, parents, coaches and athletic trainers, as well as those who<br />

practice sports medicine.<br />

Telltale Signs & Symptoms Handicard is a quick reference for practitioners. The laminated, credit-card size card features<br />

the telltale signs of CRPS on one side and a pain scale on the other. This tidy handout has been a great hit among<br />

healthcare professionals, students, and people who have CRPS/RSD.<br />

Patient Education<br />

Linda Lang, an RSDSA board member and coauthor of Living<br />

with RSDS, described the tremendous losses experienced by an<br />

individual with CRPS.<br />

What to Call It —CRPS or RSD?<br />

IN RECENT YEARS, the medical community has almost universally accepted the term Complex Regional Pain<br />

Syndrome Type I (CRPS) to describe what had been called <strong>Reflex</strong> <strong>Sympathetic</strong> <strong>Dystrophy</strong> Syndrome (RSD). CRPS is<br />

a more comprehensive term that denotes the syndrome’s regional nature and that it is not always mediated by the<br />

sympathetic nervous system. For this magazine, we used whatever term the author chose (CRPS, RSD/CRPS, or RSD).<br />

18 | T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

Lisa Delia, Maria Brown, and Jim Broatch at the 2005 Achilles Walk for Hope and Possibility fundraiser.<br />

RSDSA sponsored a team.<br />

“… [I]n publicizing RSD, we generally focus on the pain,<br />

not the disabilities that come with it-the legs and hands that no<br />

longer work, the bones that become osteoporitic, the joints that<br />

become locked, the muscles that become spastic. … There is an<br />

awful lot we leave out—how a productive member of society<br />

can become too disabled to work or take care of her children.<br />

We don’t discuss the tremendous personal losses—families,<br />

friends, jobs—that RSD wreaks … (4)”<br />

We address many of these issues in our publications, such<br />

as the RSDSA Review (a quarterly newsletter), the Support<br />

Group Newsletter (a bi-monthly electronic publication), and<br />

In Pain, Out of Work, Can’t Pay the Bills, a resource directory<br />

that identifies the governmental and private programs that<br />

can help low-income families obtain treatment and needed<br />

medication, pay their bills, and avoid losing their home.<br />

Originally published in 2001, the directory is now in its third<br />

edition. We publish several brochures as well, such as<br />

CRPS/RSD: Prevention is the Name of the Game, which links<br />

CRPS to sports injuries and the surgeries that traditionally<br />

follow them. This brochure is written for coaches and trainers,<br />

and particularly for athletes, a group we believe is at high<br />

risk for developing the syndrome.<br />

Website<br />

Most people with CRPS or persistent pain learn about RSDSA<br />

by visiting our website, www.rsds.org. In 2005, we had an average<br />

of 37,000 visits per month. Our highest traffic, 57,000 in<br />

April, was driven by a People magazine cover story revealing that<br />

Paula Abdul had been diagnosed with RSD.<br />

Our website houses all of our educational<br />

brochures (in <strong>PDF</strong> format); videos<br />

or PowerPoint ® presentations from past<br />

international conferences; scientific articles<br />

on the diagnosis, treatment, and management<br />

of CRPS that have appeared in our<br />

quarterly newsletter or in peer-reviewed<br />

journals; links to other professional and<br />

consumer sites; and much more. We<br />

encourage individuals to sign up to receive<br />

free electronic alerts about new discoveries,<br />

clinical trials, articles in the media, legislative<br />

initiatives, and upcoming events.<br />

Srinivasa N. Raja, MD, Director<br />

of Pain Research at Johns Hopkins University<br />

has created a PowerPoint ® presentation,<br />

Diagnosis and Treatment Options<br />

of RSD/CRPS, which can be downloaded<br />

for use during in-service training or for<br />

personal edification.<br />

Join RSDSA<br />

RSDSA is a vibrant organization that is<br />

sensitive to the needs and concerns of<br />

its 6,000 members and the greater<br />

CRPS community. In the Fall 2005 RSDSA Review, Norman<br />

Harden, MD, said, “Without RSDSA, progress in fighting the<br />

syndrome would likely come to a halt. Even basic and essential<br />

Revised Clinical Practice Guidelines<br />

THE THIRD EDITION of RSDSA’s Clinical Practice Guidelines<br />

will be available in hard copy and on the website by the end<br />

of March. In 2004, RSDSA approved a grant to revise the<br />

evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines, which had not been updated<br />

since 2002. RSDSA received a grant from the National Organization<br />

for Rare Diseases, Inc. (NORD) to print and distribute the guidelines.<br />

R. Norman Harden, MD, Director, Center for Pain Studies, Addison Chair,<br />

Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, edited the guidelines.<br />

Contributing authors were Stephen Bruehl, PhD, Department of<br />

Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and Allen Burton,<br />

MD, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. The guidelines<br />

include the following five chapters and a treatment algorithm:<br />

❥ Introduction and Diagnostic Considerations<br />

❥ Interdisciplinary Management<br />

❥ Pharmacotherapy of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)<br />

❥ Psychological Interventions<br />

❥ Interventional Therapies<br />

CRPS can be a difficult syndrome to treat, especially if treatment<br />

is offered piecemeal rather than in an interdisciplinary fashion as<br />

recommended. Jim Broatch, Executive Director, says, “Our goal in<br />

writing these guidelines was to make sure that those individuals<br />

suffering with CRPS receive the proper diagnosis and appropriate<br />

treatment. Through education, we hope to minimize patient<br />

losses as much as we possibly can.”<br />

T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | V O L U M E 16 , N U M B E R 1 | 19

FEATURE | BROATCH<br />

information, such as how best to make the diagnosis and what<br />

causes the disease, is lacking, and these are traditional topics<br />

funded for research by RSDSA (5).”<br />

Members include people with CRPS, their families, and<br />

practitioners. We encourage all of you to join RSDSA. Help us<br />

to promote greater awareness of CRPS among your medical<br />

colleagues and to improve the lives of individuals with CRPS<br />

and their families.<br />

Together we can make a huge difference.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Veldman HJM, Reyen HM, Arntz R, Goris JA. Signs and symptoms of<br />

reflex sympathetic dystrophy: Prospective study of 829 patients. The<br />

Lancet 1993; 342; 1012-1015.<br />

2. Oaklander et al., Evidence of focal small-fiber axonal degeneration in<br />

complex regional pain syndrome-I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). Pain.<br />

2006;120: 235-243.<br />

3. Allen G, Galer BS, Schwartz L. Epidemiology of complex regional pain<br />

syndrome; a retrospective chart review of 134 patients. Pain.<br />

1999;80:539-544.<br />

4. Lang, L. An Army of Six Million, RSDSA Review. Fall 2004.17:9.<br />

5. Broatch JW, Every Dollar for Research Counts. RSDSA Review.<br />

Fall 2005:18:3.<br />

CORPORATE<br />

M E M B E R S<br />

American Academy of Pain<br />

Management appreciates the<br />

leadership and support<br />

of its Corporate Members<br />

Electromedical Products Intl. Inc<br />

Endo Pharmaceuticals<br />

Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc<br />

Ligand Pharmaceuticals<br />

Eli Lilly and Company<br />

PainCare Holdings, Inc<br />

Purdue Pharma, L.P.<br />

20 | T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

Broaden Your Opportunity<br />

PainCare is a world class leader in the delivery of pain management solutions including:<br />

interventional pain management, minimally-invasive spine surgery, orthopedic<br />

rehabilitation, ambulatory surgery centers, and diagnostics. PainCare provides practiceenhancing<br />

services in two distinct ways, either as an ancillary service provider to existing<br />

practices or through mutually beneficial practice acquisitions.<br />

PainCare’s rapidly growing network of well-established, highly profitable owned<br />

practices and partner practices reflect the fulfillment of a need in the field of pain<br />

management to provide patients with better, more accessible solutions for pain related<br />

diagnosis and treatment. Partnering with PainCare addresses this need, while increasing<br />

practice profitability and raising the level of care for your patients.<br />

To learn how you can broaden your opportunities, call us today at 407.367.0944.<br />

www.paincareholdings.com

FEATURE | PATIENT PROFILE<br />

PEOPLE<br />

WITH CRPS<br />

THEIR STORIES AND<br />

ACCOMPLISHMENTS<br />

The following are profiles of five remarkable individuals, identified by RSDSA,<br />

who live with CRPS—and on-going pain. Although their stories are different,<br />

all have in common the desire and will to make life better for others with the<br />

condition—and the determination to live full and meaningful lives.<br />

Stephen Spagnoli<br />

STEPHEN SPAGNOLI, 46, A FORMER LANGUAGE ARTS TEACHER, MUSICIAN,<br />

AND COMPOSER FROM QUEENS, NEW YORK, ALWAYS KNEW HE HAD TALENT<br />

AS A VISUAL ARTIST, BUT HIS LIFE AS A PAINTER DIDN’T BEGIN UNTIL HE<br />

STARTED RECOVERING FROM A TERRIBLE THREE-YEAR BOUT WITH RSD. This<br />

experience, he says, was his “wake-up call.”<br />

In1997, Stephen developed a repetitive stress injury in his right arm<br />

caused by doing work around his house. Within three weeks, his left arm<br />

mirrored the same symptoms. Visits to numerous doctors produced no<br />

results. “I explained to the doctors that having pain in the other arm meant<br />

the pain had to be neuropathic, but none agreed.” In 1998, a doctor who<br />

was convinced that Stephen had tennis elbow operated on his right arm. Stephen Spagnoli<br />

“That’s when the disease exploded and I was diagnosed with RSD,”<br />

Stephen says. “The pain spread from my arms to my trunk, then to my legs, my face—everywhere. I had a full-body allodynia. I was<br />

bedridden from 1998 until 2001. I spent 15 hours out of each day in the bathtub. The quality of my life was zero. I was treated<br />

with heavy doses of morphine, but the drugs did nothing to reduce my pain.”<br />

22 | T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

The turning point came when Stephen found a doctor in<br />

Florida who specializes in RSD. “His protocols were different<br />

from any others I’d heard about. He gave me multiple injections<br />

along the edge of my spinal cord (not epidurals, but trigger-point-like<br />

injections). He got me off the morphine and put<br />

me on Buprenex. That’s when things turned around. I started<br />

moving and having energy again, and getting the pain under<br />

control (as opposed to the pain having control of me). I was<br />

still frail and walking with a cane, and I still had flare-ups, but<br />

I was no longer praying not to wake up in the morning.”<br />

When Stephen recovered enough to resume activities, he<br />

had the rare opportunity to explore “a path not taken” in his<br />

life before RSD. “I’ve always been an artist but never thought<br />

of it as a career. I had sold my illustrations to magazines and<br />

newspapers in the past, but I didn’t start expressing myself<br />

through painting until I had recovered enough from the RSD.<br />

When he began painting, Stephen’s work focused solely on<br />

various aspects of RSD. “Some were visualizations of pain and<br />

some were tactile (what the allodynia felt like). Some were<br />

images of despair and loss—the loss of who I was, my ability to<br />

enjoy being touched, and my sexuality.”<br />

Today, Stephen works in his studio each day. His abstract<br />

paintings no longer deal with pain, and he is working on the<br />

illustrations for a short story that is a metaphor for what he<br />

went through during his illness and recovery, and a book for<br />

adolescents.<br />

“I realized that I had always wanted to be an artist. The<br />

RSD was my ‘wake-up call’—just like it was a wake-up call in<br />

every other facet of my life. The RSD was a gift because it<br />

gave me the space to become what I always should have been.<br />

It also gave me an appreciation of life and my family.”<br />

Stephen says, “In a way, I used my paintings as a ‘revenge<br />

on the disease’ by making it something that could be shown. I<br />

wanted to put it up to the light.” For people who were beginning<br />

to have RSD symptoms, he wanted to encourage them<br />

to seek help immediately. He also wanted to use visual<br />

imagery to show the doctors who denied that he had RSD,<br />

that they were wrong.<br />

Stephen does not know if his condition will continue to<br />

improve, but he is hopeful. “I’m mobile and I can use my<br />

hands. I still can’t play ball with my kids, I’m not well enough<br />

to work out and keep in shape, and I still can’t play my guitar,<br />

although I try sometimes (Stephen had signed a contract with<br />

BMI, a music publishing company, prior to his illness). I just<br />

have to be patient and keep doing what I’m doing.”<br />

LOVERS<br />

Soapstone and mixed media on canvas 10x10<br />

SPASM canvas on canvas 20X18<br />

“The RSD was a gift because it gave me the<br />

space to become what I always should have been”<br />

T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | V O L U M E 16 , N U M B E R 1 | 23

PEOPLE WITH CRPS | THEIR STORIES AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS<br />

Wilson H. Hulley<br />

floor, “pawing” light switches on or off, and<br />

retrieving items from counters or even the<br />

WHEN WILSON HULLEY WAS<br />

refrigerator. Most important for someone<br />

DIAGNOSED WITH RSD, he<br />

like Wilson, Star allowed him to be independent-she<br />

acted as a cane when his bal-<br />

figured he had two choices:<br />

cave in and let the syndrome<br />

ance was compromised and, because his<br />

and the ensuing disability<br />

legs are painfully tender to the touch, she<br />

destroy him or continue to fight for the<br />

acted as a buffer between him and other<br />

rights of people with disabilities. Two years<br />

people in a crowd.<br />

before the onset of RSD, Wilson had<br />

Beyond the practical aspects, assistance<br />

joined the President’s Committee on the<br />

dogs also provide emotional support. “Pain<br />

Employment of People with Disabilities.<br />

places both physical and emotional restrictions<br />

on our lives, and although medication<br />

On the Committee, he was Special Assistant<br />

to the Executive Director, Advisor to<br />

and other treatment modalities help, those<br />

the Chairman and to The President, and<br />

of us disabled by CRPS often can use the<br />

Wilson Hulley and his assistance dog, Star<br />

a member of their Executive Staff; Wilson<br />

‘leg up’ provided by a canine companion.<br />

helped develop the language for the Americans<br />

with Disabilities Act, which President George H. Bush can break down the social and physical barriers often imposed<br />

Also, an affectionate, highly trained canine<br />

signed into law.<br />

by a disability,” he says.<br />

A car accident in 1986 left Wilson with a traumatic brain Wilson continues to be dogged in his fight for the rights of<br />

injury and the many months of rehabilitation gave him a special<br />

insight into the challenges that face people with disabilities. CRPS. As a member of the Board of Directors of RSDSA, he<br />

people with disabilities, and specifically for those who have<br />

Having held a number of senior management positions in the communicates with others who have the syndrome and has<br />

private and public sector, Wilson’s resume reads like a “Who’s served as an advocate when necessary. He is particularly interested<br />

in the plight of returning war veterans who suffer chronic<br />

Who” and his experience and contacts gave him a definite edge.<br />

For example, he was working with the Committee when the pain. Beyond the RSD community, Wilson serves on the<br />

memorial for President Franklin Roosevelt was being designed. Northwest Airlines Customer Advisory Board on Disabilities,<br />

There was a lot of discussion about whether to portray him for whom he reviews disability policies for both employees and<br />

in a wheelchair or not. Wilson recalls writing a note to then passengers. Also, having been mugged twice since becoming<br />

President Bill Clinton that said, “Mr. President. Just do it!” The disabled, Wilson recently retired from the board of directors of<br />

wheelchair won.<br />

the National Organization for Victims Assistance. And, he<br />

Wilson’s “Just do it!” attitude has served him well. For serves as the advisor to the International Association of Assistance<br />

Dog Partners; where he and Star were honored in 2004<br />

example, when he realized in 1994 that he needed help getting<br />

around, he applied for an assistance dog from the National with the Unsung Hero Award; just one of many awards and<br />

Education for Assistance Dog Services (NEADS) in Princeton, honors he has received in his lifetime of serving others.<br />

Massachusetts. Star, a British Black Labrador Retriever, helped Like others who suffer from CRPS, the magnitude of Wilson’s<br />

personal loss is huge but unlike so many others, he contin-<br />

Wilson negotiate the world for 10 years (she recently passed<br />

away at the age of 12. He is awaiting his second assistance dog ues to be empowered to make the world a better, safer, and<br />

from NEADS). Although we don’t automatically associate assistance<br />

dogs with people in pain, they can do multiple things<br />

happier place for those who are disabled.<br />

that make life manageable, such as picking things up from the<br />

“ … an affectionate, highly trained canine can break<br />

down the social and physical barriers often<br />

imposed by a disability.” WILSON HULLEY<br />

24 | T H E PA I N P R A C T I T I O N E R | S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

Barbara Schaffer<br />

IN 1988, BARBARA SCHAFFER, a 38-year-old vocational rehabilitation<br />

counselor, developed RSD from a minor injury at<br />

work. Although her RSD was diagnosed and treated almost<br />

immediately, the disease progressed rapidly. Exercise exacerbated<br />

her condition, other complications set in, and nothing<br />

relieved her pain. Yet in spite of her worsening physical condition,<br />

Barbara continued working at the job she loved for two<br />

more years (until the program shut down), and began taking<br />

action to help others who were living with RSD.<br />

Shortly after being diagnosed in 1988, Barbara launched an<br />

RSD support group in her area. And in 1992, she published an<br />

RSD newsletter and launched the first RSD website.<br />

Barbara’s group also ran four CME conferences for doctors<br />

and nurses through Geisinger Medical Center, a tertiary-care<br />

teaching hospital in the area.<br />

Two years ago, Barbara worked with others (Rick Ulrich<br />

and Jenny Dye, both of whom have RSD) to get an RSD bill<br />

passed in Pennsylvania. “The bill calls for<br />

educating the public and medical community<br />

about RSD. We were successful because<br />

State Representative Merle Phillips worked<br />

with us. He’d known me and Rick, and he’d<br />

seen what RSD had done to us. Once the<br />

bill was passed, the State Department of<br />

Health held a meeting with providers from<br />

all over the state who treat people with<br />

RSD. The purpose of this meeting was to<br />

find out what the providers wanted done,<br />

and that’s how the outreach program was<br />

developed. New York State put out an RSD<br />

bill the year before, but they’ve didn’t have<br />

Barbara and Paul Schaffer<br />

the money to implement it. In Pennsylvania<br />

the money came out of the Department of Health budget. So<br />

the implementation may not be as good as we would like, but<br />

we do have pamphlets in all the Department of Health sites<br />

and there is RSD information on their website.” Pennsylvania<br />

is one of the three states in the country to have passed RSD<br />

legislation.<br />

Today, at 56, Barbara has had to cut back her activities, but<br />

that hasn’t stopped her from working for others with RSD.<br />

Doctors refer patients to her, and she gives support to them<br />

over the phone. She also contributes her time to RSDSA. Last<br />

year she assisted RSDSA staff in organizing a conference in her<br />

area; she writes articles for their newsletter that focus on RSD<br />

and the arts; and she has worked on the organization’s annual<br />

fundraising dinner.<br />

At home, Barbara spends time with her husband (he takes<br />

care of their three grandchildren while their daughter and<br />

son-in-law are at work). “I’ve been lucky to be involved with<br />

my grandchildren. I’m a big part of their lives, which is very<br />

important to me.”<br />

Barbara is philosophical about the challenges<br />

of living with RSD. “I have lost the<br />

ability to do many of the things that I<br />

loved, and I have mourned their loss. But I<br />

continue to find new things to do and new<br />

ways to do old things. In filling my days<br />

with activities and friends and my grandchildren,<br />

I have learned that there are<br />

many ways I can enjoy life. This is a constant<br />

challenge because RSD is always<br />

changing. But isn’t change one of the constants<br />

of life? I try to remember that life<br />

has made me no promises, that each day is<br />

a gift, and that I get to choose whether I<br />

suffer or enjoy it.”<br />

“ I try to remember that life has made me no promises,<br />

that each day is a gift, and that I get to choose<br />