The Journal of San Diego History - San Diego History Center

The Journal of San Diego History - San Diego History Center

The Journal of San Diego History - San Diego History Center

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Charles C. Painter<br />

<strong>San</strong> Jacinto Viejo, a Mexican land<br />

grant <strong>of</strong> 1844. When the ranch was<br />

partitioned in 1882, Matthew Byrne,<br />

a <strong>San</strong> Bernardino businessman,<br />

acquired 700 acres that included the<br />

village. In 1883, an adjoining 3,100<br />

acres were set aside as a reservation<br />

by Executive Order. Byrne sued in<br />

<strong>San</strong> <strong>Diego</strong> County Superior Court<br />

in 1883 to remove the villagers.<br />

Jackson followed the case closely<br />

and hired the Los Angeles law firm<br />

<strong>of</strong> Brunson & Wells at her own<br />

expense to defend the Indians. See<br />

her article, “<strong>The</strong> Fate <strong>of</strong> Saboba,”<br />

<strong>The</strong> New York Independent (December<br />

13, 1883): 1-2. When the government<br />

refused to cover Brunson &<br />

Wells’ expenses, they withdrew,<br />

and Painter appealed to President<br />

Chester A. Arthur, who appointed<br />

Shirley C. Ward as a special attorney<br />

to carry on their defense. After the<br />

<strong>San</strong> <strong>Diego</strong> County Superior Court<br />

ruled against the villagers, Ward<br />

carried an appeal to the California<br />

State Supreme Court in 1886, arguing<br />

that under Mexican law, the<br />

villages had held a possessory right<br />

to their lands, and that by the treaty<br />

<strong>of</strong> Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United<br />

States had pledged to honor all<br />

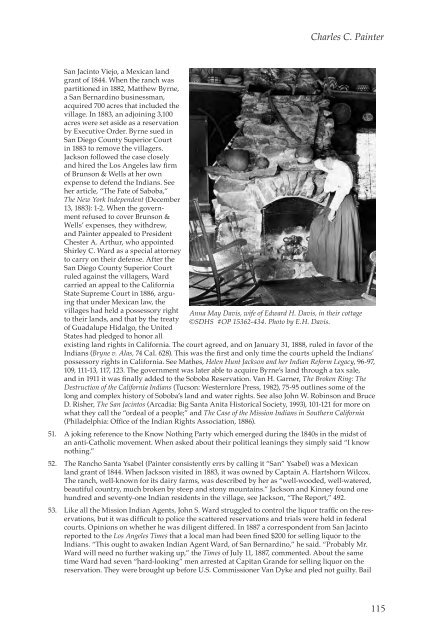

Anna May Davis, wife <strong>of</strong> Edward H. Davis, in their cottage<br />

©SDHS #OP 15362-434. Photo by E.H. Davis.<br />

existing land rights in California. <strong>The</strong> court agreed, and on January 31, 1888, ruled in favor <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Indians (Bryne v. Alas, 74 Cal. 628). This was the first and only time the courts upheld the Indians’<br />

possessory rights in California. See Mathes, Helen Hunt Jackson and her Indian Reform Legacy, 96-97,<br />

109, 111-13, 117, 123. <strong>The</strong> government was later able to acquire Byrne’s land through a tax sale,<br />

and in 1911 it was finally added to the Soboba Reservation. Van H. Garner, <strong>The</strong> Broken Ring: <strong>The</strong><br />

Destruction <strong>of</strong> the California Indians (Tucson: Westernlore Press, 1982), 75-95 outlines some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

long and complex history <strong>of</strong> Soboba’s land and water rights. See also John W. Robinson and Bruce<br />

D. Risher, <strong>The</strong> <strong>San</strong> Jacintos (Arcadia: Big <strong>San</strong>ta Anita Historical Society, 1993), 101-121 for more on<br />

what they call the “ordeal <strong>of</strong> a people;” and <strong>The</strong> Case <strong>of</strong> the Mission Indians in Southern California<br />

(Philadelphia: Office <strong>of</strong> the Indian Rights Association, 1886).<br />

51. A joking reference to the Know Nothing Party which emerged during the 1840s in the midst <strong>of</strong><br />

an anti-Catholic movement. When asked about their political leanings they simply said “I know<br />

nothing.”<br />

52. <strong>The</strong> Rancho <strong>San</strong>ta Ysabel (Painter consistently errs by calling it “<strong>San</strong>” Ysabel) was a Mexican<br />

land grant <strong>of</strong> 1844. When Jackson visited in 1883, it was owned by Captain A. Hartshorn Wilcox.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ranch, well-known for its dairy farms, was described by her as “well-wooded, well-watered,<br />

beautiful country, much broken by steep and stony mountains.” Jackson and Kinney found one<br />

hundred and seventy-one Indian residents in the village, see Jackson, “<strong>The</strong> Report,” 492.<br />

53. Like all the Mission Indian Agents, John S. Ward struggled to control the liquor traffic on the reservations,<br />

but it was difficult to police the scattered reservations and trials were held in federal<br />

courts. Opinions on whether he was diligent differed. In 1887 a correspondent from <strong>San</strong> Jacinto<br />

reported to the Los Angeles Times that a local man had been fined $200 for selling liquor to the<br />

Indians. “This ought to awaken Indian Agent Ward, <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Bernardino,” he said. “Probably Mr.<br />

Ward will need no further waking up,” the Times <strong>of</strong> July 11, 1887, commented. About the same<br />

time Ward had seven “hard-looking” men arrested at Capitan Grande for selling liquor on the<br />

reservation. <strong>The</strong>y were brought up before U.S. Commissioner Van Dyke and pled not guilty. Bail<br />

115

![[PDF] The Journal of San Diego History Vol 52: Nos 1 & 2](https://img.yumpu.com/25984149/1/172x260/pdf-the-journal-of-san-diego-history-vol-52-nos-1-2.jpg?quality=85)

![[PDF] The Journal of San Diego History - San Diego History Center](https://img.yumpu.com/25984131/1/172x260/pdf-the-journal-of-san-diego-history-san-diego-history-center.jpg?quality=85)