Probate, Estate Planning & Trust Section - South Carolina Bar ...

Probate, Estate Planning & Trust Section - South Carolina Bar ...

Probate, Estate Planning & Trust Section - South Carolina Bar ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

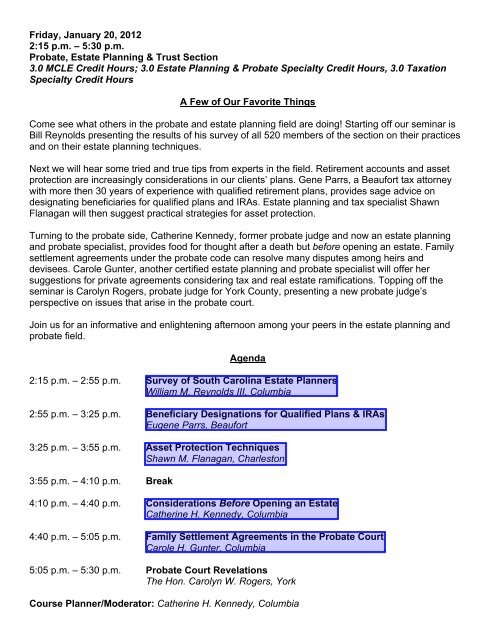

Friday, January 20, 2012<br />

2:15 p.m. – 5:30 p.m.<br />

<strong>Probate</strong>, <strong>Estate</strong> <strong>Planning</strong> & <strong>Trust</strong> <strong>Section</strong><br />

3.0 MCLE Credit Hours; 3.0 <strong>Estate</strong> <strong>Planning</strong> & <strong>Probate</strong> Specialty Credit Hours, 3.0 Taxation<br />

Specialty Credit Hours<br />

A Few of Our Favorite Things<br />

Come see what others in the probate and estate planning field are doing! Starting off our seminar is<br />

Bill Reynolds presenting the results of his survey of all 520 members of the section on their practices<br />

and on their estate planning techniques.<br />

Next we will hear some tried and true tips from experts in the field. Retirement accounts and asset<br />

protection are increasingly considerations in our clients’ plans. Gene Parrs, a Beaufort tax attorney<br />

with more then 30 years of experience with qualified retirement plans, provides sage advice on<br />

designating beneficiaries for qualified plans and IRAs. <strong>Estate</strong> planning and tax specialist Shawn<br />

Flanagan will then suggest practical strategies for asset protection.<br />

Turning to the probate side, Catherine Kennedy, former probate judge and now an estate planning<br />

and probate specialist, provides food for thought after a death but before opening an estate. Family<br />

settlement agreements under the probate code can resolve many disputes among heirs and<br />

devisees. Carole Gunter, another certified estate planning and probate specialist will offer her<br />

suggestions for private agreements considering tax and real estate ramifications. Topping off the<br />

seminar is Carolyn Rogers, probate judge for York County, presenting a new probate judge’s<br />

perspective on issues that arise in the probate court.<br />

Join us for an informative and enlightening afternoon among your peers in the estate planning and<br />

probate field.<br />

Agenda<br />

2:15 p.m. – 2:55 p.m. Survey of <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> <strong>Estate</strong> Planners<br />

William M. Reynolds III, Columbia<br />

2:55 p.m. – 3:25 p.m. Beneficiary Designations for Qualified Plans & IRAs<br />

Eugene Parrs, Beaufort<br />

3:25 p.m. – 3:55 p.m. Asset Protection Techniques<br />

Shawn M. Flanagan, Charleston<br />

3:55 p.m. – 4:10 p.m. Break<br />

4:10 p.m. – 4:40 p.m. Considerations Before Opening an <strong>Estate</strong><br />

Catherine H. Kennedy, Columbia<br />

4:40 p.m. – 5:05 p.m. Family Settlement Agreements in the <strong>Probate</strong> Court<br />

Carole H. Gunter, Columbia<br />

5:05 p.m. – 5:30 p.m. <strong>Probate</strong> Court Revelations<br />

The Hon. Carolyn W. Rogers, York<br />

Course Planner/Moderator: Catherine H. Kennedy, Columbia

Beneficiary Designations<br />

for<br />

Qualified Plans and IRAs*<br />

*Or, Ten Things Every Attorney Should Know About Beneficiary<br />

Designations<br />

Eugene Parrs<br />

Harvey & Battey, P.A.<br />

1001 Craven Street<br />

Beaufort, SC 29902<br />

Tel: 843-524-3109<br />

E-Mail: eparrs@gmail.com<br />

I. Introduction<br />

A. A client’s beneficiary designation for a qualified plan (i.e., 401(k) plans, pension<br />

plans, and 403(b) plans) or an individual retirement account (IRA) are the<br />

“weakest link” in chain of estate planning documents. It is the most likely place<br />

a mistake will occur.<br />

B. With beneficiary designations there is generally no “construction proceeding”<br />

that can be brought after the client’s death to fix a mistake. The decedent’s<br />

“intent” does not change the effect of the designation.<br />

C. Errors with plan and IRA payouts are magnified because distributions can be<br />

large and they are subject to full estate tax and income tax.<br />

D. There are several reasons why so many errors occur with beneficiary<br />

designations.<br />

1. Clients do not realize how much of their estate is controlled by<br />

beneficiary designations, not their wills. Clients simply do not review<br />

or update designations after death of a spouse, divorce, or remarriage.<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Plan and IRA Distributions <br />

Page 1

2. The estate planning attorney is rarely asked to actually prepare or<br />

review the designation form.<br />

3. The beneficiary designation forms are confusing, even for attorneys.<br />

4. Many excellent financial consultants and investment advisors know<br />

very little about the correct choices for the client.<br />

5. The tax laws for qualified plan and IRA distributions are complex.<br />

II.<br />

Income Tax Overview<br />

A. Qualified plan and IRA distributions are controlled by IRC §401(a)(9), which<br />

impose the “required minimum distribution” (“RMD”) rules.<br />

B. Qualified plans, as opposed to IRAs, may have limited choices for payouts at<br />

death. Most qualified plans require the spouse to be the beneficiary. You<br />

must check the plan to see if it offers the payout option that suits the client’s<br />

needs.<br />

III.<br />

Ten Things to Know About Beneficiary Designations<br />

#1. The “Bible” for qualified plan and IRA distributions is Life and Death<br />

<strong>Planning</strong> 2011 7 th Edition, by Natalie Choate. (www.ataxplan.com)<br />

#2. If the client maintains his/her 401(k) account after retirement, it is almost<br />

always advantageous to transfer the account to an IRA. The 401(k) plan<br />

most likely has very limited payment options. Most IRAs offer a wide range<br />

of options.<br />

#3. The beneficiary designation in a qualified plan must be implemented<br />

notwithstanding evidence of a client’s mistake or misunderstanding.<br />

Kennedy v. The DuPont SIP, 129 S.Ct. 865 (2009). See Attachment A.<br />

#4. Look to qualified plan and IRA distributions to fulfill charitable bequests.<br />

#5. Take advantage of “look-through” trusts. See Attachment B.<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Plan and IRA Distributions <br />

Page 2

#6. Take advantage of the “separate account” opportunity in cases of multiple<br />

beneficiaries. This will allow each beneficiary to use his/her own life<br />

expectancy for RMD purposes rather that the age of the oldest beneficiary.<br />

See IRS Reg. §1.401(a)(9)-8.<br />

#7. Provide your client with a “beneficiary designation letter” instructing them<br />

how to make their designations. See Attachment C.<br />

#8 Always have the client name a contingent, or secondary, beneficiary. This<br />

will (i) protect the family in case the primary beneficiary predeceases, (ii)<br />

provide a planning option to disclaim after the client’s death, and (iii)<br />

preclude the estate from becoming the beneficiary by default.<br />

#9. It is almost always a mistake to make “the estate” the beneficiary of a<br />

qualified plan or IRA.<br />

#10. It is almost always a good idea to name the spouse as the beneficiary of the<br />

qualified plan or IRA.<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Plan and IRA Distributions <br />

Page 3

Attachment A

The U.S. Supreme Court Rules on Beneficiary Disputes<br />

Eugene Parrs<br />

Harvey & Battey, P.A.<br />

1001 Craven Street<br />

Beaufort, SC 29902<br />

Tel: 843-524-3109<br />

E-Mail: eparrs@gmail.com<br />

The U.S. Supreme Court decided a case in 2009 that adds certainty to the law of<br />

beneficiary designations in qualified retirement plans. The case is Kennedy v. The DuPont SIP,<br />

129 S.Ct. 865 (2009).<br />

Clients are surprised by how much of their wealth is controlled at their death by<br />

beneficiary designations, not a will. Life insurance, annuities, IRAs, 401(k)’s and almost all<br />

other retirement plans, both qualified and nonqualified, pass at death according to beneficiary<br />

designations. For many clients those assets are a large portion of their wealth. Incorrect,<br />

outdated, and unmade beneficiary designations are the most likely source of a mistake in a<br />

client’s estate plan.<br />

ERISA, the federal pension law, has been on the books since 1974. Since then, plan<br />

administrators have faced problems when disappointed relatives of a deceased participant<br />

challenge a payout because they believe the beneficiary designation was “wrong.” Plan<br />

administrators are liable if the “wrong” person is paid. Must a plan administrator evaluate<br />

challenges to the beneficiary designation to determine if it was “right”? The Supreme Court<br />

recently answered that question. Administrators are obligated to pay the person designated on<br />

the beneficiary form and look no further.<br />

Background This takes us to the story of William Kennedy. He was employed by<br />

DuPont and married Liv Kennedy in 1971. Mr. Kennedy was a participant in two DuPont plans:<br />

the DuPont Savings and Investment Plan (SIP) and the DuPont Pension and Retirement Plan.<br />

The SIP was a 401(k) plan and the pension plan was a defined benefit plan. Mr. Kennedy and<br />

Liv were divorced in 1994. In the divorce decree, Liv received a portion of Mr. Kennedy’s<br />

pension benefits, but she waived her rights to the SIP. In 1997 a qualified domestic relations<br />

order, or “QDRO,” was entered transferring the pension benefits to Liv. (A “QDRO” is a special<br />

court order that transfers retirement benefits to an ex-spouse as part of a divorce.) There was no<br />

QDRO for the SIP.<br />

Mr. Kennedy died in 2001. It was then discovered that he had never changed his SIP<br />

beneficiary designation naming Liv, although he had been free to do so after the 1994 divorce.<br />

Over the objections of Mr. Kennedy’s estate, the SIP plan administrator honored the beneficiary<br />

designation and paid Liv the SIP balance of $402,000. Mr. Kennedy’s estate sued, claiming the<br />

SIP beneficiary designation naming Liv was void because she had waived her rights in the<br />

divorce decree. The administrators of the SIP said they were obligated by ERISA to follow the<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Page 1

plan documents, which included the beneficiary designation naming Liv, and disregard the<br />

divorce decree. If Mr. Kennedy had not wanted Liv to receive the SIP death benefits, he should<br />

have filed a new SIP beneficiary designation form after the divorce.<br />

The US Supreme Court held that Liv’s waiver in the divorce proceeding was not effective<br />

under ERISA and that the SIP had to pay Liv under the beneficiary designation. The Court said<br />

“there is no exception to the plan administrator’s duty to act in accordance with the plan<br />

documents.”<br />

ERISA sets out four principal responsibilities for plan fiduciaries: They must (i) operate<br />

the plan for the exclusive benefit of participants, (ii) invest assets prudently, (iii) diversify<br />

investments, and (iv) administer the plan according to it documents. It is the last one that came<br />

into play here.<br />

Before we conclude that William was inattentive or foolish in not filing a new SIP<br />

beneficiary designation, there’s an interesting fact noted in his estate’s brief filed with the<br />

Supreme Court.<br />

Four days after the divorce, on June 7, 1994, William Kennedy<br />

designated his only child, Kari Kennedy, as his only beneficiary on a<br />

DuPont beneficiary designation form. Its title was “COMPANY<br />

PAID SURVIVOR BENEFITS (PRE-RETIREMENT) SECTION<br />

XVI OF THE PENSION AND RETIREMENT PLAN.”<br />

That’s odd. The ink was not even dry on the divorce decree before Mr. Kennedy updated his<br />

beneficiary designation for the pension plan but not the SIP. Yet, in the seven years from his<br />

divorce until his death, he ignored a $400,000 SIP benefit he certainly wanted to pass to his only<br />

child. Perhaps he thought the form he signed four days after his divorce covered the SIP. The<br />

title to that beneficiary designation form might mislead anyone. Or, as was pointed out in the<br />

oral argument, Mr. Kennedy may have thought the divorce decree nullified the SIP beneficiary<br />

designation naming Liv. The Supreme Court opinion said a QDRO could have been entered<br />

terminating Liv’s rights under the SIP. However, under the divorce decree no SIP benefits were<br />

to be paid to her. What divorce lawyer obtains a QDRO for a retirement plan when the exspouse<br />

is getting nothing from it? (Note: QDROs are complicated. It took three years in this<br />

case for the pension QDRO to be entered).<br />

Nonetheless, the Supreme Court has spoken, and it did so unanimously. At the death of a<br />

plan participant, the plan administrator of a qualified plan must pay the person named on the<br />

beneficiary designation form filed by the participant (or the person named in a QDRO). There<br />

are no exceptions.<br />

Significance of This Case<br />

take from this case.<br />

Everyone who deals with qualified plans has something to<br />

First, plan administrators now have an unambiguous “bright line” rule on whom<br />

to pay death benefits: the person named in a beneficiary designation or a QDRO. Plan<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Page 2

administrators need not, and must not, consider extrinsic documents, non-QDRO court decrees,<br />

and whining relatives. This assures that named beneficiaries are paid quickly and plan<br />

administrators are protected in doing so. As the Court said, “ERISA forecloses any justification<br />

for enquiries into nice expressions of intent…” Employers and plan administrators should<br />

remind participants that beneficiary designations are critical and should be reviewed regularly.<br />

Second, plan participants are responsible for updating beneficiary designations.<br />

Participants must also know what they are signing. Employers maintain many benefit plans,<br />

such as life insurance, 401(k) plans, pension plans, ESOPs, 403(b) plans, 457 plans, and nonqualified<br />

plans, each requiring a “beneficiary.” In some companies, a single form may be used<br />

for all plans. In other companies, there may be a separate form for each plan. Beneficiary forms<br />

use fancy words and legalese that can easily confuse the participant. Many employees do not<br />

understand English. Look what happened to Mr. Williams. Four days after his divorce he<br />

signed a form which changed his pension beneficiary, and my guess is that he thought it covered<br />

his SIP too. It didn’t.<br />

Third, estate planners -- lawyers, CPAs, and financial and investment advisors ---<br />

must be especially vigilant in making sure clients have the proper beneficiary designations in<br />

place.<br />

Other Considerations There are three additional aspects of this case worth noting.<br />

First, some may be troubled by the windfall enjoyed by the ex-wife, Liv. She gets<br />

divorced, ex-hubby dies years later, and $400,000 that she had bargained away in the divorce<br />

falls in her lap. What’s more, the U.S. Supreme Court says she gets it! Where’s the justice?<br />

Well, not so fast. In a footnote in the decision, the Court goes out of its way to suggest that the<br />

estate can sue the ex-wife under state law after the benefits are distributed to her. When a<br />

beneficiary designation is contested the dynamics will be (i) an immediate payout to the named<br />

beneficiary followed by (ii) a negotiated settlement or litigation among the disputing claimants in<br />

state courts. For the plan administrator, it’s a beautiful thing. A distribution to the named<br />

beneficiary gets it out of the picture with full immunity.<br />

Second, many states have laws which automatically terminate a spouse’s right to<br />

inherit property upon the entry of a divorce decree. This case says that those automatic<br />

terminations will not apply in the case of beneficiary designations under qualified retirement<br />

plans.<br />

Third, this case does not apply to IRAs.<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Page 3

Attachment B

Revisiting IRA “Look-Through” <strong>Trust</strong>s<br />

Eugene Parrs<br />

Harvey & Battey, P.A.<br />

1001 Craven Street<br />

Beaufort, SC 29902<br />

Tel: 843-524-3109<br />

E-Mail: eparrs@gmail.com<br />

Using a trust as an IRA beneficiary offers planning opportunities. Rather than the<br />

IRA owner naming a spouse, child, or grandchild as the direct IRA beneficiary, the owner<br />

instead names a trust for that person as the beneficiary. The trust may protect the beneficiary,<br />

achieve a tax result, or both.<br />

In 2001 the IRS updated its regulations on how trusts could be used as IRA<br />

beneficiaries. Those regulations made IRA trusts a legitimate estate planning device. The recent<br />

combination of market turmoil, recession, and aging baby-boomers has made the IRA trust<br />

particularly attractive. In fact, several financial services companies have developed<br />

comprehensive programs for IRA trusts. These programs make IRA trusts more user friendly to<br />

both clients and their advisors.<br />

Qualified plan distributions, like IRA distributions, can also be made to trusts.<br />

However, with qualified plans there are complexities that should be avoided. I will address only<br />

IRA trusts here.<br />

Background IRAs must satisfy the minimum distribution rules when the IRA<br />

owner reaches age 70-1/2. Payments are spread over the owner’s life expectancy. At the<br />

owner’s death, distributions can be made over the life expectancy of the IRA’s “designated<br />

beneficiary.” These are referred to as “stretch IRAs.”<br />

If a trust is named as the IRA beneficiary, there can be a problem because a trust,<br />

unlike an individual, has no life expectancy over which post-death distributions can be<br />

calculated. However, if the trust meets IRS requirements, we can “look through” the trust and<br />

treat the trust beneficiary as the designated beneficiary of the IRA. We then use that<br />

beneficiary’s life expectancy to calculate minimum distributions to the trust. Were it not for this<br />

“look through” rule, the IRA would have to be paid out over a much shorter period after the<br />

owner’s death, thereby losing long term tax deferral.<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Page 1

Note: Here’s how to understand the concept. The IRA is tax exempt. The IRA trust<br />

is not. The trust will have money from the IRA only briefly each year. The trustee<br />

withdraws the annual minimum distribution (or more, if desired) from the IRA and<br />

deposits the funds in the trust. The trustee then distributes the funds from the trust to<br />

the trust beneficiary. The balance stays in the IRA for continued tax deferred growth.<br />

The IRA trust may be empty until next’s years minimum distribution is received.<br />

Requirements for “Look Through” <strong>Trust</strong>s There are five simple requirements<br />

for a trust to qualify for “look through” status.<br />

1. The trust must be valid under state law.<br />

2. The trust must be irrevocable, or will, by its terms, become irrevocable<br />

at the death of the IRA owner.<br />

3. The trust beneficiaries must be identifiable from the trust instrument.<br />

4. Certain documents must be provided to the IRA custodian or<br />

administrator.<br />

5. The trust beneficiary must be an individual.<br />

Four Scenarios for IRA <strong>Trust</strong>s There are at least four instances when you<br />

should consider a trust for an IRA.<br />

1. Intended Beneficiary is a Child If the intended IRA beneficiary is a<br />

minor, using a trust is obvious. As long as the trust qualifies under the “look through” rules, the<br />

life expectancy of the child can be used for post-death minimum distributions.<br />

For example, at grandfather’s death he names an IRA trust as beneficiary<br />

of a $100,000 IRA. The grandson is the sole beneficiary of the trust. Under the IRS annuity<br />

tables the life expectancy of a 5 year old is 77.7 years. So, in the first year after the grandfather’s<br />

death, the IRA must distribute only 1/77.7 to the trust (that’s 1.287%, or $1,287). The balance of<br />

the fund remains in the IRA for continued tax deferred growth. In each subsequent year, the<br />

minimum distribution divisor is reduced by 1. The tax deferral opportunity is enormous. Of<br />

course, more than the minimum distribution can be withdrawn from the IRA at any time, such as<br />

when the grandson is in college.<br />

2. Intended Beneficiary Is an Adult Who Needs Protection In this case the<br />

intended IRA beneficiary is an adult, but the adult has problems, is in a bad marriage, or does not<br />

have the financial self-discipline to take only the minimum distribution every year. The IRA<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Page 2

trust, with an independent trustee, may protect the beneficiary from some of his creditors or<br />

himself.<br />

3. Using a Credit Shelter <strong>Trust</strong> A married client has a large estate, much of<br />

it in IRAs. The client has no other “non-IRA” assets with which to fund the credit shelter trust<br />

for his wife in his will. The client could name his wife as the direct IRA beneficiary, but that<br />

would squander his otherwise available estate tax exemption (currently $3.5 million).<br />

The client should establish a “look through” IRA trust naming his wife as<br />

beneficiary of the trust. IRA assets earmarked for the trust will not qualify for the estate tax<br />

marital deduction, but they will be covered by up to $3.5 million of the exemption. Minimum<br />

distributions calculated on the wife’s life expectancy (and more, if necessary) will be taken from<br />

the IRA, put into the “look through” trust, and then paid to the wife each year. The rest stays in<br />

the IRA for continued tax deferred growth.<br />

4. QTIP <strong>Trust</strong> for Wife in a Second Marriage In this example the IRA<br />

owner is married for the second time. He has substantial IRA assets. If his wife survives, he will<br />

need the estate tax marital deduction, but he does not want to name his current wife as outright<br />

IRA beneficiary. He needs to protect his wife during her lifetime, but after her death he wants<br />

the remaining IRA balance paid to his children from a previous marriage.<br />

In this case the husband should use an IRA “look through” trust as beneficiary of<br />

his IRA. His wife would be the sole beneficiary of the trust. The trust can be drafted to qualify<br />

for the estate tax marital deduction if a “QTIP” election is made. The wife then lives off the IRA<br />

distributions made to the trust and paid out to her. At her death the remaining IRA assets pass to<br />

the husband’s children.<br />

Practical Considerations<br />

through” trust.<br />

Here are some housekeeping tips when using a “look<br />

• Roll qualified plan assets into an IRA. Many qualified plans do not permit payout<br />

options that would be needed for a “look through” trust to work. By contrast, IRAs<br />

offer every permissible payout arrangement.<br />

• Use a separate IRA trust for each intended designated beneficiary. If there is more<br />

than one trust beneficiary, you must use the life expectancy of the eldest.<br />

• I prefer to not co-mingle IRA distributions into a “look through” trust that is expected<br />

to receive non-IRA assets. When I use an IRA “look through” trust in a will, I<br />

segregate it from all other trusts in that will. There is no legal requirement for this,<br />

but I believe it minimizes the likelihood of mistakes when distributions are made<br />

from year to year.<br />

• Verify that the IRA beneficiary designation naming the IRA trust is properly filed<br />

with the IRA custodian and accurately identifies the intended IRA trust.<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Page 3

• Do not confuse the client’s general revocable “living trust” for a “look-through” trust.<br />

Many living trusts do not have the special provisions to qualify them as a “look<br />

through” trust after the client’s death.<br />

• Finally, a word of caution. This memo is a general overview intended to illustrate the<br />

basics of “look through” trusts. There are many complexities I have not discussed,<br />

and the examples in this memo are simplistic.<br />

Conclusion IRA “look through” trusts are an important estate planning tool. While<br />

certainly not for everyone, IRA trusts afford solutions to many clients’ special circumstances.<br />

Setting up a “look through” trust requires careful planning, draftsmanship, and monitoring. It<br />

also requires close coordination with the client, his financial advisor, his CPA, and his estate<br />

planning attorney.<br />

Eugene Parrs <br />

Page 4

Attachment C

Mr. and Mrs. Elvis Presley<br />

Graceland Mansion<br />

Memphis, TN<br />

[Date]<br />

Dear Elvis and Madonna:<br />

I would like to explain how you should title your assets and update your beneficiary<br />

designations to conform to the provisions of your new wills.<br />

The objective is to minimize estate settlement costs. If this is done properly, there<br />

should be virtually no settlement costs (i.e., legal fees and “probate expenses”) at the first death.<br />

After the first death, we would make further adjustments to reduce expenses in anticipation of<br />

the second death.<br />

Title to Assets You should title your real estate, bank accounts, and investment<br />

accounts as “joint tenants with right of survivorship.” At the first death, these assets will pass to<br />

the survivor of you automatically, making the probate of the will unnecessary.<br />

Beneficiary Designations Life insurance, annuities, and retirement plans are controlled<br />

by beneficiary designations, not your wills. There is a separate form for each insurance policy,<br />

IRA, and retirement plan.<br />

Life Insurance and Annuities: The primary beneficiary should be the spouse, and<br />

the contingent beneficiaries should be your children, Larry, Moe, and Curly.<br />

IRAs and 401(k) Plans The primary beneficiary should be the spouse, and the<br />

contingent beneficiaries should be your children, Larry, Moe, and Curly.<br />

I caution that beneficiary designation forms are sometimes confusing and filled with legal<br />

jargon. Mistakes can cause serious financial or tax problems after your death. If you have any<br />

question whatsoever about updating your forms, fax them to me and I will walk you through<br />

them. If you bring them in I will help you fill them out.<br />

If you have any questions please call me at any time.<br />

Very truly yours,<br />

Eugene Parrs<br />

Initials: ________<br />

_________

Asset Protection Techniques<br />

January 20, 2012<br />

presented by Shawn M. Flanagan, Esq.<br />

Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice, LLP<br />

5 Exchange Street<br />

Charleston, SC 29401<br />

(843) 722-3400<br />

1. This outline relies on the following recommended reading material. Jacob<br />

Stein, “Practical Primer and Radical Approach to Asset Protection,” 38 <strong>Estate</strong> <strong>Planning</strong> 6, pages<br />

21 – 29 (June 2011) (sometimes referred to herein as “Stein”). <strong>Bar</strong>ry S. Engel’s book, Asset<br />

Protection <strong>Planning</strong> Guide 2 nd Edition (CCH 2005) (sometimes referred to herein as “Engel”).<br />

2. Goal. According to Engel, the goal to asset protection planning is to have the<br />

client weather a claim at least moderately better than the client otherwise would have. This is<br />

achieved by removing the client’s name from the legal title to assets while allowing the client to<br />

retain some benefit and control of the assets. In general, the greater the protection, the less the<br />

flexibility. The greater the flexibility, the less the protection.<br />

3. Analysis. Asset protection planning is generally asset specific. Analyze — how<br />

does a structure work from a theoretical standpoint and how does a structure work from a<br />

practical standpoint. See Stein.<br />

4. Taxes. Asset protection planning will not aid a client in evading the payment of<br />

taxes. Most plans are drafted to be tax neutral (as much as possible) with regard to income, gift,<br />

and estate tax considerations. For example, an irrevocable trust would usually be a “grantor<br />

trust” for income tax purposes and an incomplete transfer for gift and estate tax purposes.<br />

5. Fraudulent Conveyance Laws. Each state has a fraudulent transfer statute. A<br />

creditor who succeeds in challenging a transfer under the statute can unwind the transfer.<br />

“<strong>Planning</strong> early is always the best defense against a fraudulent transfer challenge.” Stein at page<br />

23.<br />

S.C. Code Ann. §27-23-10 (commonly referred to as the Statute of Elizabeth)<br />

renders void any transfer of property made with intent or purpose to delay, hinder or defraud<br />

creditors. Carr v. Guerard, 365 S.C. 151, 616 S.E.2d 429 (2005). In <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong>, fraudulent<br />

transfers may be set aside by “existing creditors” and “subsequent creditors.” An existing<br />

creditor means a person with respect to whom the claim occurred before the transfer was made.<br />

A subsequent creditor is “a creditor to whom Debtor becomes indebted after the transfer but<br />

whose claim was foreseen by Debtor prior to the alleged fraudulent transfer.” In re J.R. Deans<br />

Co., Inc., 249 B.R. 121, 130-132 (Bkrtcy.D.S.C. 2000).<br />

“Proving a fraudulent transfer … is not an easy task… [T]he existence of an asset<br />

protection structure, whether or not it is susceptible to a fraudulent transfer attack, will almost<br />

WCSR 7084580v1 1

always result in a better settlement for the debtor.” Stein at page 22. “The exercise of [the<br />

fraudulent transfer law] remedy will place [the clients] in exactly the same position as if they had<br />

chosen to do nothing. Consequently, clients can only improve their position by trying to protect<br />

their assets. For them, the risk of a fraudulent transfer challenge carries no downside. Even the<br />

transaction costs incurred in implementing the asset protection structure are not a consideration,<br />

as that money would have been lost to the lender in any case.” Stein at page 23.<br />

6. Qualified retirement plans. A “qualified retirement plan” includes 401(k) plans,<br />

profit sharing plans, and pension plans. Qualified retirement plans are very highly protected<br />

from creditors under a federal statute known as ERISA (Employee Retirement Income Security<br />

Act). 29 U.S.C. section 1001 et seq. See Patterson v. Shumate, 112 S.Ct. 2242 (1992) and<br />

Guidry v. Sheetmetal Pension Fund, 493 U.S. 365 (1990). The federal statute trumps a state<br />

fraudulent transfer law.<br />

For a qualified retirement plan to qualify for federal protection under ERISA, it<br />

needs to have at least one participant in who is not an owner of the business or owner’s spouse.<br />

See for example In the Matter of Robert L. Branch, 16 F.3d 1225 (7 th Cir. 1994) and In re<br />

Lowenschuss, 170 F.3d 923 (9 th Cir. 1999), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 877.<br />

7. IRAs. The Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005,<br />

P.L. 109-8, §224 (effective October 17, 2005) extended some federal creditor protection to IRAs.<br />

Pursuant to <strong>Section</strong> 244 of the 2005 Bankruptcy Act, all tax-qualified retirement plan benefits<br />

and any such benefits rolled into an IRA are excluded from the bankruptcy estate. 11 USC<br />

§522(b)(3)(C); §522(b)(4); and §522(d)(12). Plus up to an additional $1,000,000 of other IRA<br />

contributions are also excluded from the bankruptcy estate. 11 USC §522(n).<br />

The federal protection added in 2005 is in addition to the state protection that<br />

IRAs have enjoyed for years. See S.C. Code Ann. §15-41-30(A)(13).<br />

8. Residential real estate. A traditional way of protecting the home (and any other<br />

assets for that matter), is to title the asset in the name of the non-risk or lower-risk spouse.<br />

One alternative is to title the home in both names as tenants-in-common with right<br />

of survivorship (TICWROS). TICWROS was meant to replace “tenancy by entirety” when that<br />

latter form of owning real estate was abolished in <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong>. Real estate (particularly a<br />

residence) owned by a married couple as TICWROS is arguably protected from creditors.<br />

“Tenancy by the entirety” is real estate owned by a husband and wife. About<br />

one-third (⅓) of the states (including North <strong>Carolina</strong>) recognize tenancy by the entirety. Most<br />

states that allow tenancy by the entireties will not allow a creditor to force a partition or attach a<br />

debtor spouse’s interest in a personal residence. Note: A client should consider tenancy by the<br />

entirety for the couple’s mountain home in North <strong>Carolina</strong>.<br />

A TICWROS “cannot be destroyed by the unilateral act of one tenant through an<br />

act such as partition.” In one case, the language in the deed that the <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> Supreme<br />

Court recognized as establishing a TICWROS is as follows: “for and during their joint lives and<br />

WCSR 7084580v1 2

upon the death of either of them, then to the survivor of them, his or her heirs and assigns forever<br />

in fee simple…” Smith v.Cutler, 366 S.C. 546, 623 S.E.2d 644 (2005).<br />

Remember the homestead exemption. Pursuant to S.C. Code Ann. §15-41-<br />

30(A)(1), a debtor’s interest in his/her “residence” (real property and personal property) up to a<br />

maximum of $50,000 in value (as indexed for inflation) is exempt from attachment by any court<br />

or bankruptcy proceeding. If a house is owned by a husband and wife and a claim is made<br />

against both of them, then the maximum exemption is $100,000. Encumbering real estate lowers<br />

the equity in the real estate. Steps must be taken to protect the loan proceeds.<br />

9. <strong>Section</strong> 529 Plans. A <strong>Section</strong> 529 college savings tuition plan allows you to own<br />

an account under the plan for the benefit of your child’s post-secondary school education needs.<br />

States that provide a statutory creditor protection for <strong>Section</strong> 529 Plans include Alaska,<br />

Colorado, Maine, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Wisconsin. You can frontload a <strong>Section</strong><br />

529 Plan with five years worth of annual exclusion gifts. This allows a person to contribute<br />

$65,000 in one year ($13,000 times five) without any gift tax consequences. Note: If a client<br />

takes advantage of the frontloading, the client cannot make any other annual exclusion annual<br />

gifts to or on behalf of the same beneficiary for five (5) years.<br />

10. Life insurance. Any unmatured life insurance contract owned by a debtor (other<br />

than a credit life insurance contract) is exempt from attachment by a court or bankruptcy<br />

proceeding. S.C. Code Ann. §15-41-30(A)(8).<br />

There are two other statutes which protect life insurance. Proceeds of group life<br />

insurance contracts and benefits of accident and disability contracts are exempt from claims of<br />

the creditors of the insured. S.C. Code Ann. §§38-63-40(B) and (C). Also generally exempt<br />

from the creditors of the insured are proceeds and cash surrender values of life insurance payable<br />

to a beneficiary (other than the insured’s estate) in which such proceeds and cash surrender<br />

values are expressed to be for the primary benefit of the insured’s spouse, children or<br />

dependents. Amounts over $50,000 must meet more conditions. S.C. Code Ann. §38-63-40(A)<br />

and §38-65-90.<br />

Foreign Life Insurance. Several foreign jurisdictions have laws which expressly<br />

protect that jurisdiction’s insurance and annuity products from seizure by a client’s creditors.<br />

Two of the more well known of these foreign jurisdictions are Switzerland and the Bahamas.<br />

Chapter 6 of the Asset Protection <strong>Planning</strong> Guide, by <strong>Bar</strong>ry S. Engel (CCH 2005) focuses on the<br />

insurance and annuity statutes of Switzerland as a model. “The judgment of a court outside the<br />

insurance company’s resident jurisdiction will generally not be honored to the extent in conflict<br />

with these statutory protections.” Engel at 601.01. Independent proceedings to reach a Swiss<br />

policy have to be instituted in Switzerland and adjudicated under Swiss debt collection and<br />

bankruptcy laws—this is a sizeable impediment to a creditor. Engel at 625.<br />

11. Corporations. Consider electing to be a “statutory close corporation” under our<br />

corporate code and an S corporation for tax purposes. It is arguably harder to “pierce the veil” of<br />

a statutory close corporation and an S corporation. See Hunting v. Elders, 359 S.C. 217, 597<br />

WCSR 7084580v1 3

S.E.2d 803 (Ct.App. 2004). Also, if the business qualifies, consider electing to be a professional<br />

corporation since SC Code Ann. §43-19-200 limits who can be a shareholder in a PA.<br />

12. Limited Liabilities Companies. About the only asset that you should resist<br />

placing in an LLC is a personal residence. Liquid assets (for example, bank and brokerage<br />

accounts) as well as real estate can be titled in the name of an LLC.<br />

A client owning a distributional interest in an LLC is in a better position vis-à-vis<br />

a creditor than a client owning assets in the client’s individual name. The creditor’s exclusive<br />

remedy is limited to a charging order or a foreclosure of the LLC interest. S.C. Code Ann. §33-<br />

44-504(e).<br />

A charging order constitutes a lien on the judgment debtor’s distributional<br />

interest. S.C. Code Ann. §33-44-504(b). A charging order entitles the judgment creditor to<br />

whatever distributions would otherwise be due to the debtor whose interest is subject to the<br />

order. A charging order or foreclosure does not grant the creditor any management or<br />

voting rights. The creditor has no say in the timing or amount of those distributions. The<br />

charging order does not entitle the creditor to accelerate any distributions or to otherwise<br />

interfere with the management and activities of the legal entity. See Uniform Limited<br />

Partnership Act section 703, Comments. Although a debtor can not receive distributions,<br />

“debtors can frequently pull assets out of the entity using loans and guaranteed payments.”<br />

Uniform Limited Liability Company Act section 101(5) and Stein at page 25.<br />

“The foreclosure remedy is rarely useful to a creditor…the purchaser at the<br />

foreclosure sale has the rights of only a transferee.” Stein at page 25. S.C. Code Ann. §33-44-<br />

504(b). A creditor does not want allocations of tax items with no corresponding distributions of<br />

cash.<br />

Recommended provisions for the LLC operating agreement:<br />

• Establish a multi-member LLC.<br />

• If you have any concern about making sure a creditor has no voting rights,<br />

use a manager run LLC making the potential debtor a non-manager<br />

member.<br />

• Make interests non-assignable, or assignable only with the consent of the<br />

other members.<br />

• Consider including a trigger that requires redemption of a member’s<br />

interest at a predetermined price in the event of a collection action. See<br />

S.C. Code Ann. §33-44-504( c)(3).<br />

• Eliminate a transferee’s right to request a judicial dissolution of the<br />

LLC pursuant to S.C. Code Ann. §33-44-801(5).<br />

• Rather than being forced to make distributions to members in accordance<br />

with their percentage interests, you can insert a clause directing the<br />

manager to withhold distributions from a debtor-member in the event of a<br />

charging order while continuing distributions to the other members.<br />

WCSR 7084580v1 4

13. IRREVOCABLE TRUSTS. A trust used for asset protection purposes must be<br />

irrevocable and include a spendthrift provision, and should be discretionary. Under the best<br />

circumstances, someone other than the settlor would serve as the trustee and family members<br />

other than the settlor would be the beneficiaries.<br />

In general, a court may authorize a creditor or assignee of a trust beneficiary to<br />

reach the beneficiary’s interest by attachment of present or future distributions to or for the<br />

benefit of the beneficiary. S.C. Code Ann. §§62-7-501(a). However, spendthrift trusts and<br />

discretionary trusts are generally exempt from creditor attachment. See S.C. Code Ann. §62-7-<br />

501(b), as well as §§62-7-502, 62-7-503, and 62-7-504.<br />

If the debtor is the trustee, appoint a third party trust protector with authority to<br />

remove and replace the trustee and/or veto distributions.<br />

A problem arises whenever the debtor wants to include himself as a beneficiary.<br />

If a debtor establishes a trust in which the debtor is also a beneficiary, the trust is considered<br />

“self-settled” and the debtor is not afforded the protection that usually applies when an<br />

irrevocable trust includes a spendthrift provision. “[A] creditor or assignee of the settlor may<br />

reach the maximum amount that can be distributed to or for the settlor’s benefit.” S.C. Code<br />

Ann. §§62-7-505(a)(2).<br />

A settlor can generally select the law that will govern the trust. S.C. Code Ann.<br />

§§62-7-107(1). As discussed in the next paragraph, some states now allow creditor protection to<br />

self-settled trusts. It is not clear whether another state’s law will be respected given (1) the full<br />

faith and credit clause of the U.S. Constitution and (2) the fact that a state does not have to<br />

recognize the law of another state that violates its public policy. See Restatement 2d Conflict of<br />

Laws section 280. Still, it is worth considering.<br />

Domestic asset protection trust (DAPT). There are at least twelve (12) states<br />

where a self-settled spendthrift trust is protected from a settlor’s creditors. Such a trust is known<br />

as a “domestic asset protection trust”. If a client is not willing to incur the expense and<br />

complexity of a foreign asset protection trust (FAPT), then the client might want to take a look at<br />

a DAPT. Caveat: It has yet to be tested whether a DAPT state must recognize a judgment from<br />

another state under the Full Faith and Credit Clause of the U.S. Constitution. The following<br />

states have enacted asset protection trust law: Alaska, Colorado (to a limited extent), Delaware,<br />

Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, <strong>South</strong> Dakota, Tennessee, Utah<br />

and Wyoming. To get the benefit of the laws in a DAPT state, a client must have some<br />

connection with the state. For example, Alaskan law requires that some assets of the DAPT be<br />

located in Alaska. It may be enough of a connection if one of the co-trustees is domiciled in<br />

Alaska. As with their corporate law, Delaware strives to keep on the cutting edge of this form of<br />

legislation. Bank of America has a trust department in Delaware set up specifically to serve as a<br />

trustee of a DAPT. There is a law firm in Delaware the presenter is aware of that will serve as a<br />

co-trustee of a DAPT.<br />

Jacob Stein suggests coupling a DAPT with an LLC: “If the debtor does not have<br />

any family members who may be appointed as the beneficiaries of the trust (to get around the<br />

WCSR 7084580v1 5

self-settled trust issue), designate the governing law of the state that affords protection to a selfsettled<br />

trust, and then create a limited liability company owned by the debtor and designate it as<br />

the beneficiary of the trust.” Stein at page 27. Mr. Stein’s article does not explain the reason for<br />

his recommendation. The benefit may be two-fold: First, the settlor is not a trust beneficiary<br />

under this arrangement. Second, distributions are made to the LLC, rather than to or for the<br />

direct benefit of the settlor.<br />

A transfer of a client’s assets into an irrevocable trust may be challenged as a<br />

fraudulent transfer. If this is a concern, consider making the trust governed by Nevada law.<br />

“Nevada has a two-year statute of limitations for challenging the transfer of assets into an<br />

irrevocable, spendthrift trust governed by Nevada law.” Nev. Rev. Stat. § 166.170 and Stein at<br />

page 27.<br />

Do not give the debtor or potential debtor a general power of appointment since<br />

that may allow a creditor to reach the trust assets. The debtor or potential debtor should not be a<br />

remainder beneficiary. Also, if the settlor is a beneficiary, draft the trust agreement so as to not<br />

allow a reversion of trust assets to the settlor’s estate.<br />

Qualified Personal Residence <strong>Trust</strong> (QPRT). A QPRT involves a transfer of a<br />

personal residence to an irrevocable trust. The settlor retains the right to live there for a term (for<br />

example, 12 years). At the end of the term, the home is either deeded outright to the remainder<br />

beneficiaries (e.g., the settlor’s spouse or children) or continues in trust for the benefit of the<br />

remainder beneficiaries. The settlor might retain the right to lease the home from the<br />

remainderman or the trustee at the end of the term. A QPRT is a self-settled spendthrift trust.<br />

As stated earlier, in <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong>, a settlor who is also a beneficiary of a trust may not use the<br />

trust as a shield against the settlor’s creditors. S.C. Code Ann. §62-7-505(a)(2). A creditor can<br />

go after the settlor’s interest in the QPRT (but not the residence) during the term of the QPRT. A<br />

creditor faced with a QPRT is likely to either not pursue the matter or settle for something less<br />

than what he normally would.<br />

14. Foreign asset protection trust (FAPT). Some countries have legislation that<br />

protect the assets of a self-settled spendthrift trust. A “creditor’s job is made much more difficult<br />

and a lot more expensive when assets are placed offshore. When the assets are offshore, in many<br />

instances litigation to reach the assets will take place offshore. Forcing the creditor to engage in<br />

an economic analysis of the case may produce a more favorable result for the debtor.” Stein at<br />

page 28.<br />

A FAPT is one of the most protective planning vehicles that a planner can design<br />

and implement for a client. Engel at Chapter 10, 1001, page 175. The trust law of some foreign<br />

jurisdictions is simply more thorough and more protective than domestic trust law, including<br />

specifically those states that have enacted DAPT legislation. Engel at Chapter 10, 1175, page<br />

240.<br />

The biggest downsides to a FAPT are the complexity (clients like to keep things<br />

as simple as possible) and the cost.<br />

WCSR 7084580v1 6

184.<br />

The following diagram is reproduced from Engel, Chapter 10, 1025.04, on page<br />

Costs. The issue becomes whether the set-up and maintenance costs associated<br />

with a FAPT are worth it to an individual, based on the individual’s own weighing of cost versus<br />

benefit. The fees and costs associated with FAPT planning do not generally vary with the size of<br />

an estate. Net worth alone is not typically a factor in fees and costs; rather, the factors include<br />

whether multiple trusts will be used in any given plan, and the number of related or underlying<br />

WCSR 7084580v1 7

entities that are to be utilized. Another variable in fees will be whether there are any major<br />

complexities associated with a client’s particular situation or planning goals. Engel in Chapter<br />

10, 1035.01, on page 194.<br />

Robert Lowes’ article in the February 21, 2003 issue of Medical Economics<br />

(“Protect your assets before you’re sued”) indicates that it takes “$20,000 or more” to create<br />

offshore trusts and cites an author on the subject who recommends going offshore only if you<br />

have $500,000 or more in liquid assets (meaning stocks, bonds, and such, as opposed to real<br />

estate and retirement plans).<br />

An October 14, 2003 Wall Street Journal article by Rachel Emma Silverman<br />

(“Litigation Boom Spurs Efforts to Shield Assets–Doctors, Executives Turn to <strong>Trust</strong>s That Are<br />

Off-Limits to Creditors”) states that “offshore asset-protection trusts can cost anywhere from<br />

$20,000 to $50,000 to set up, plus annual administrative fees of $2,000 to $5,000 and assetmanagement<br />

fees of about 1% on the assets placed in trust.” Ms. Silverman’s article also states<br />

that “because of the high fees, asset-protection trusts generally don’t make sense unless you’re<br />

willing to put at least $1 million in them.”<br />

WCSR 7084580v1 8

January 20, 2012<br />

A Few of Our Favorite Things<br />

CONSIDERATIONS BEFORE <br />

OPENING AN ESTATE <br />

Catherine H. Kennedy. Esq. <br />

Cer$fied Specialist in <strong>Estate</strong> <strong>Planning</strong> and <strong>Probate</strong> Law <br />

ckennedy@turnerpadget.com <br />

TURNER PADGET GRAHAM & LANEY, PA

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

I. Alterna6ves to Full Administra6on <br />

1. Will Filed only (Form 306) <br />

• No assets <br />

• Will placed on record

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

2. Will <strong>Probate</strong>d only (Form 300) <br />

• No assets <br />

• Will actually declared valid <br />

• Informa6on provided to heirs and devisees <br />

(Form 305)

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

3. Small <strong>Estate</strong> Affidavit (Form 420) <br />

• Net value of assets less than $10,000 (If <br />

vehicle, include VIN, make and model, year <br />

of the vehicle to be transferred) <br />

• 30 days from death <br />

• No applica6on/pe66on for appointment of <br />

PR <br />

• Assets delivered by possessor to successors <br />

• Successors liable to PR or creditors

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

4. Transfer of Vehicle with SCDMV <br />

• Cer6ficate of 6tle with alterna6ve owners-‐-‐<br />

i.e. , names are separated by “or” <br />

• Applica6on for Cer6ficate of Title <br />

(SCDMV Form 400) <br />

• Proper Iden6fica6on <br />

• Cer6fied copy of the death cer6ficate not <br />

required

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

5. Appointment of Special Administrator <br />

• Obtain medical records <br />

• Enter safety deposit box <br />

• Accept service <br />

enforce lien <br />

establish liability covered by insurance <br />

• Protect and preserve assets <br />

See Sec6on 62-‐3-‐614

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

II.<br />

Sec6on 62-‐3-‐108-‐-‐Ten year <br />

limita6on on commencement of <br />

administra6on or probate <br />

Summons and Pe66on to determine heirs <br />

See Sec6ons 62-‐3-‐105 and 106

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

III. Summary Administra6on-‐-‐ <br />

Sole Heir(s)/Devisee(s) = PR(s) <br />

• Consider renuncia6on of right to administer <br />

• Consider nomina6on as PR <br />

• Consider Disclaimers <br />

• Consider private agreements under Sec6on <br />

62-‐3-‐912

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

IV. Formal <strong>Probate</strong> <br />

• Summons and Pe66on Required <br />

• Responsive pleading by party opposing probate <br />

required <br />

See Sec6on 62-‐3-‐404

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

V. Creditor Claims <br />

• Ul6mate 6me limit for filing pre-‐death claims is <br />

1 year from date of death <br />

See Sec6on 62-‐3-‐803 <br />

• Consider wai6ng to open the estate

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

VI. Proof of Death <br />

• See Sec6on 62-‐1-‐107 for presump6on of death <br />

• Consider what date you want person to be <br />

declared deceased—at the end of 5 years or <br />

earlier

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

VII. Domicile of Decedent <br />

• Consider Intestacy laws <br />

• Consider Proof of Will <br />

• Consider rights of surviving spouse <br />

• Consider rights of dependents <br />

• Consider ease of administra6on

Considera6ons Prior to Administra6on <br />

Final Advice <br />

Think before opening an estate. There may be <br />

strategic advantages to be gained in planning

Family Settlement Agreements in the <strong>Probate</strong> Court<br />

Statutes authorizing private agreements.<br />

1. §62-3-912-Private agreements among successors to decedent binding on personal<br />

representative.<br />

(Allows successors to vary estate distribution, whether testate or intestate, without court<br />

approval.)<br />

Subject to the rights of creditors and taxing authorities, competent successors may agree among<br />

themselves to alter the interests, shares, or amounts to which they are entitled under the will of<br />

the decedent, or under the laws of intestacy, in any way that they provide in a written contract<br />

executed by all who are affected by its provisions. The personal representative shall abide by the<br />

terms of the agreement subject to his obligation to administer the estate for the benefit of<br />

creditors, to pay all taxes and costs of administration, and to carry out the responsibilities of his<br />

office for the benefit of any successors of the decedent who are not parties. Personal<br />

representatives of decedents' estates are not required to see to the performance of trusts if the<br />

trustee thereof is another person who is willing to accept the trust. Accordingly, trustees of a<br />

testamentary trust are successors for the purposes of this section. Nothing herein relieves trustees<br />

of any duties owed to beneficiaries of trusts.<br />

2. § 62-3-1101. Effect of approval of agreements involving trusts, inalienable interests,<br />

or interests of third persons.<br />

A compromise of a controversy as to admission to probate of an instrument offered for formal<br />

probate as the will of a decedent, the construction, validity, or effect of a probated will, the rights<br />

or interests in the estate of the decedent, of a successor, or the administration of the estate, if<br />

approved by the court after hearing, is binding on all the parties including those unborn,<br />

unascertained, or who could not be located. An approved compromise is binding even though it<br />

may affect a trust or an inalienable interest. A compromise does not impair the rights of creditors<br />

or of taxing authorities who are not parties to it. A compromise approved pursuant to this section<br />

is not a settlement of a claim subject to the provisions of <strong>Section</strong> 62-5-433.<br />

See Univ. of S. California v. Moran, 365 S.C. 270, 283, 617 S.E.2d 135, 142 (Ct. App. 2005)<br />

Page 1 of 19

We hold the Anderson <strong>Trust</strong> is the beneficiary of Mrs. Anderson's estate, and Moran, as<br />

trustee, is the person required to execute the compromise agreement. Because only the<br />

trust, as holder of the beneficial interest, must sign the compromise agreement, the circuit<br />

court did not err in concluding the requirements of section 62-3-1102 were met. <strong>Section</strong><br />

62-3-1102(3) mandates that an interested person receive notice of a proposed<br />

compromise, and allows the interested person to participate in the proceedings, including<br />

objecting to any compromise agreement. Accordingly, the order of the circuit court is<br />

AFFIRMED.<br />

3. <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> Code § 62-3-1102. Procedure for securing court approval of<br />

compromise.<br />

The procedure for securing court approval of a compromise is as follows:<br />

(1) The terms of the compromise shall be set forth in an agreement in writing which shall be<br />

executed by all competent persons and parents acting for any minor child having beneficial<br />

interests or having claims which will or may be affected by the compromise. Execution is not<br />

required by any person whose identity cannot be ascertained or whose whereabouts is unknown<br />

and cannot reasonably be ascertained.<br />

(2) Any interested person, including the personal representative or a trustee, then may submit<br />

the agreement to the court for its approval and for execution by the personal representative, the<br />

trustee of every affected testamentary trust, and other fiduciaries and representatives.<br />

(3) Upon application to the court and after notice to all interested persons or their<br />

representatives, including the personal representative of the estate and all affected trustees of<br />

trusts, the court, if it finds that the contest or controversy is in good faith and that the effect of the<br />

agreement upon the interests of persons represented by fiduciaries or other representatives is<br />

just and reasonable, shall make an order approving the agreement and directing all fiduciaries<br />

subject to its jurisdiction to execute the agreement. Minor children represented only by their<br />

parents may be bound only if their parents join with other competent persons in execution of the<br />

compromise. Upon the making of the order and the execution of the agreement, all further<br />

disposition of the estate is in accordance with the terms of the agreement.<br />

Page 2 of 19

4. <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> Code § 62-7-111. Nonjudicial settlement agreements.<br />

(a) For purposes of this section, “interested persons” means persons whose consent would be<br />

required in order to achieve a binding settlement were the settlement to be approved by the court.<br />

(b) Interested persons may enter into a binding nonjudicial settlement agreement with respect to<br />

only the following trust matters:<br />

(1) The approval of a trustee's report or accounting;<br />

(2) Direction to a trustee to perform or refrain from performing a particular<br />

administrative act or the grant to a trustee of any necessary or desirable administrative power;<br />

(3) The resignation or appointment of a trustee and the determination of a trustee's<br />

compensation;<br />

(4) Transfer of a trust's principal place of administration; and<br />

(5) Liability of a trustee for an action relating to the trust.<br />

(c) Any interested person may request the court to approve a nonjudicial settlement agreement,<br />

to determine whether the representation as provided in Part 3 was adequate, and to determine<br />

whether the agreement contains terms and conditions the court could have properly approved.<br />

Remember: The resolution that the beneficiaries reach may have gift or estate tax<br />

ramifications.<br />

The Private Agreement that went bad!!!<br />

Examples of Private Agreements<br />

Parker v. Shecut, 340 S.C. 460, 497, 531 S.E.2d 546, 566 (Ct. App. 2000) rev'd, 349 S.C. 226,<br />

562 S.E.2d 620 (2002)<br />

Mary Shecut died October 30, 1992. Her will left all of her assets in equal shares to her three<br />

children, Ann, Bo and Win. Her sons, Bo and Win, were the personal representatives. Mary<br />

Shecut owned a lot of real estate. The three beneficiaries decided among themselves as to how<br />

they wanted the estate to be distributed. Win wanted farm land, while Bo and Ann wanted the<br />

Page 3 of 19

estate’s commercial property and a beach house at Edisto. On April 6, 1993, all three<br />

beneficiaries presented themselves in the office of the attorney representing the Personal<br />

Representatives. All three beneficiaries told the attorney representing the Personal<br />

Representatives that they had reached a mutual decision as to the distribution of the estate. They<br />

were in a hurry to put their agreement in writing. The attorney drafted the agreement that same<br />

day. The three beneficiaries were from out of town and stayed in town until the agreement was<br />

complete and fully executed. The attorney who prepared the agreement went to a meeting<br />

outside of the office, and left the draft with another attorney in the firm for the beneficiaries to<br />

review. When the attorney returned to the office, she was informed that the beneficiaries had<br />

executed the agreement. Win almost immediately upon executing the agreement wanted to<br />

rescind it. When the attorney representing the beneficiaries could not immediately prepare the<br />

deeds, the beneficiaries hired another attorney to draft them. The newly-hired attorney prepared<br />

deeds of distribution giving all of the properties to the three beneficiaries as tenants in common<br />

and partition deeds, which deeded the property as set forth in the agreement. Ann not only<br />

refused to sign the partition deeds, she sued claiming that the agreement was void. The court<br />

upheld and ordered specific performance of the agreement.<br />

Anne challenged both the validity of the agreement and whether the lower court should have<br />

ordered specific performance. Challenge of the Private Agreement was based on:<br />

1. Ann argued that her brothers abandoned the agreement because deeds of distribution<br />

were prepared. The attorney who drafted the deeds testified that he was retained to<br />

transfer the real estate pursuant to the agreement.<br />

2. Ann argued that her brother (Win) repudiated the agreement and then failed to timely<br />

execute an addendum that reaffirmed it.<br />

Agreement to admit lost will to probate<br />

Some probate courts will admit to informal probate a will that is lost if all beneficiaries of<br />

the will and all heirs at law agree to admit the will to probate.<br />

Sample document:<br />

Page 4 of 19

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA ) IN THE PROBATE COURT<br />

)<br />

COUNTY OF RICHLAND )<br />

)<br />

IN THE MATTER OF SAMUEL FRICK<br />

) CASE NUMBER 2007ES40______<br />

PRIVATE AGREEMENT<br />

This private agreement has been entered into between Janice F. Smith and Stan Frick, the only heirs at<br />

law of Samuel Frick. Janice F. Smith and Stan Frick are hereinafter referred to as “the heirs.”<br />

WHEREAS, Samuel Frick died on October 14, 2007. At the time of his death, he owned his home<br />

located at 5210 Hamrick Court, Columbia, <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> 29209.<br />

WHEREAS, Samuel Frick executed a Last Will and Testament on March 20, 2003, a copy of which is<br />

attached hereto as Exhibit A.<br />

WHEREAS, the only beneficiaries of said will are the heirs.<br />

WHEREAS, although the original will cannot be located, the heirs believe that the decedent intended for<br />

the will dated March 20, 2003 be his Last Will and Testament.<br />

NOW THEREFORE, the heirs agree to have the will dated March 20, 2003 admitted to probate. After all<br />

of the debts and administrative expenses of the decedent have been paid, the parties agree to the<br />

distribution of the estate pursuant to the terms of said will.<br />

The parties request that the Richland County <strong>Probate</strong> Court admit the will dated March 20, 2003 to<br />

probate.<br />

IN WITNESS THEREOFF, the parties have executed this agreement on the date indicated.<br />

Witnesses as to Janice F. Smith:<br />

___________________________________________<br />

___________________________________________<br />

Witnesses as to Stan Frick:<br />

__________________________________________<br />

__________________________________________<br />

Warning—some courts still require formal probate.<br />

__________________________________<br />

Janice F. Smith<br />

Date: ____________________________<br />

_________________________________<br />

Stan Frick<br />

Date: ____________________________<br />

Page 5 of 19

Agreement used to Open <strong>Estate</strong><br />

Several years ago, another attorney asked me to help get an estate opened. He was going on<br />

vacation, and it needed to be opened. These were the facts:<br />

1. A bank trust department was named as personal representative in will of decedent<br />

2. The bank trust department renounced its right to serve as personal representative<br />

3. The will poured over to a grantor trust<br />

4. The grantor (decedent) had removed the bank trust department as trustee of his trust and<br />

at his death he was serving as trustee<br />

5. The trust indicated that the trustee would be a corporation<br />

6. Since the trust was to be distributed outright at the grantor’s death, the beneficiaries saw<br />

no reason to have a corporate trustee<br />

7. All beneficiaries were competent adults<br />

8. There was no family conflict!!<br />

The solution I found was as follows:<br />

1. All beneficiaries of <strong>Trust</strong> signed an Agreement to name a successor <strong>Trust</strong>ee<br />

2. All devisees under the will nominated another devisee—(Chris Jones in the Agreement)<br />

to serve as personal representative (Used Form 302PC)<br />

3. The court opened the estate—informal—no hearing was required.<br />

Agreement used:<br />

Page 6 of 19

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA )<br />

) AGREEMENT TO NAME SUCCESSOR TRUSTEE<br />

COUNTY OF RICHLAND )<br />

Agreement made between Jack Smith, John Smith, James Smith, Bryce Smith, Chris Jones,<br />

Audrey Jones, Jimmy Jones, Katherine Jones, Lee Jones, Joe Smith, Sara S. Dodge, and Tanya Brown.<br />

WHEREAS, on August 9, 1996, George Smith, as Settlor, entered into a <strong>Trust</strong> agreement with<br />

Original Bank of <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong>, as <strong>Trust</strong>ee. Said trust is known as the George Smith <strong>Trust</strong>.<br />

trust.<br />

WHEREAS, by merger Original Bank of <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> became Successor Bank, N.A.<br />

WHEREAS, Article III of said trust agreement gave the Settlor the right to amend or change the<br />

WHEREAS, Settlor’s wife, Ruth Jones Smith, died January 1, 2000. Her estate was probated<br />

in Richland County, Case 2000-ES-40-04987.<br />

WHEREAS, on October 31, 2007, George Smith completed a Living <strong>Trust</strong> Account Form with<br />

Edward Jones. This form showed “G. Smith as the trustee of the George Smith <strong>Trust</strong> dated August 9,<br />

1996”.<br />

WHEREAS, the <strong>Trust</strong> Agreement had a typing error in Article VII (b)(ii) in that Tanya Brown<br />

was called Tanya Broon.<br />

WHEREAS, on December 3, 2007, George Smith removed Successor Bank, N.A. as trustee. He<br />

moved the trust assets to Edward Jones and began serving as trustee of said trust.<br />

WHEREAS, in December of 2007, assets with a value of $358,750.67 were moved to Edward<br />

Jones and titled in the George Smith <strong>Trust</strong> dated August 9, 1996.<br />

WHEREAS, George Smith died on December 31, 2009, leaving the trust with no trustee.<br />

WHEREAS, at the death of George Smith, this account was still in existence and held securities<br />

in the name of the George Smith <strong>Trust</strong>.<br />

WHEREAS, Article VIII (3) of said trust reads, “If any successor trustee as herein defined shall fail<br />

to qualify as trustee hereunder, or for any reason should cease to act in such capacity, the successor or<br />

substitute trustee shall be some other bank or trust company qualified to do business in the state of the<br />

Settlor’s domicile at the time of the Settlor’s death, which successor substitute trustee shall be designated<br />

in a written instrument filed with the court having jurisdiction over the probate of the Settlor’s estate and<br />

signed by the majority of adult beneficiaries.”<br />

WHEREAS, <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> Code 1976 §62-7-704, as Amended, indicates that a vacancy in a<br />

trusteeship of a noncharitable trust that is required to be filled must be filled in the following order of<br />

priority: (1) by a person designated in the terms of the trust to act as success trustee; (2) by a person<br />

appointed by unanimous agreement of the qualified beneficiaries.<br />

WHEREAS, <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> Code 1976 §62-7-103 (12) defines a “qualified beneficiary” as the<br />

living persons who will take the trust income or principal.<br />

WHEREAS, pursuant to Article VII (4) of the <strong>Trust</strong> Agreement because both Settlor and his wife<br />

are deceased, the trust is to terminate and be distributed as follows:<br />

Page 7 of 19

a) All interest in any real property held by the <strong>Trust</strong>ee when this Paragraph (4) becomes<br />

operative shall be distributed to such of Jack Smith, John Smith, James Smith, and Bryce<br />

Smith, who are then living; and<br />

b) All the rest, residue and remainder of the trust estate in the percentages set forth below:<br />

a. 75% to Chris Jones, Audrey Jones, Jimmy Jones; Katherine Jones, Lee Jones,<br />

or such of them as shall be living when this Paragraph (4) becomes operative;<br />

and<br />

b. 25% to Joe Smith, Sara S. Dodge and Tanya Broon (should be Brown), or such<br />

of them as shall be living when this Paragraph (4) becomes operative.<br />

WHEREAS, the parties to this agreement are all of the “qualified beneficiaries” of the George<br />

Smith <strong>Trust</strong>.<br />

NOW THEREFORE, the qualified beneficiaries of this trust believe that Chris Jones is a proper<br />

person to serve as <strong>Trust</strong>ee of the George Smith <strong>Trust</strong> and they agree as follows:<br />

1. The vacant trustee of the George Smith <strong>Trust</strong> shall be filled by Chris Jones.<br />

2. Chris Jones shall serve without bond.<br />

3. Chris Jones shall immediately become trustee of the George Smith <strong>Trust</strong>. He shall<br />

receive the assets from the estate of George Smith, and administer and distribute those<br />

assets as well as the assets which are already in the trust pursuant to the terms of said<br />

trust.<br />

4. By signing this agreement, Chris Jones agrees to serve as trustee and to faithfully carry<br />

out the terms of said trust.<br />

This agreement may be executed in any number of counterparts and by different parties in<br />

separate counterparts. Each counterpart when so executed shall be deemed to be an original and all of<br />

which together shall constitute one and the same agreement.<br />

This agreement has been executed by all of the qualified beneficiaries of the George Smith <strong>Trust</strong><br />

dated August 9, 1996.<br />

Witness as to Jack Smith<br />

__________________________<br />

__________________________________<br />

Jack Smith<br />

Date: _____________________________<br />

Remainder of signatures were omitted---<br />

ALL PARTIES MUST SIGN THE AGREEMENT IN THE SAME MANNER<br />

Page 8 of 19

AGREEMENT TO CONVEY REAL ESTATE<br />

Facts.<br />

1. Client’s mother died in 2002. Her estate was not probated.<br />

2. Client’s mother had 4 children, 2 of whom were children of decedent.<br />

3. Deceased and client’s mother divorced in 2009. Divorce decree indicated that the<br />

deceased would pay her $40,000 for her interest in the house and she would convey title<br />

to Deceased.<br />

4. Client’s mother never conveyed property to deceased.<br />

Solution:<br />

1. Opened estates of client’s mother and the deceased.<br />

2. Private Agreement—Children of client’s mother agreed to quit claim their interest in<br />

house to children of deceased.<br />

Agreement used:<br />

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA )<br />

)<br />

)<br />

)<br />

COUNTY OF RICHLAND )<br />

PRIVATE AGREEMENT REGARDING THE ESTATE<br />

OF PATSY FRASER<br />

Agreement made the 29 th day of August, 2011, between the heirs-at-law of Patsy Fraser, who<br />

are: Jeff Smith, Pat Pool, Evan Smith, Sally Fraser and Karen Fraser, regarding the distribution of the real<br />

estate owned by the <strong>Estate</strong> of Patsy Fraser.<br />

WHEREAS, Patsy Fraser died intestate on April 14, 2002. She was a resident of Richland<br />

County, <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong>, and her estate is being administered in the Richland County <strong>Probate</strong> Court as<br />

Case Number 2011 ES 40 00728.<br />

WHEREAS, Harry Fraser died intestate on November 4, 2010. He was a resident of Richland<br />

County, <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong>, and his estate is being administered in the Richland County <strong>Probate</strong> Court as<br />

Case Number 2011 ES 40 00824.<br />

WHEREAS, the heirs at law of Harry Fraser are Sally Fraser and Karen Fraser.<br />

WHEREAS, at the time of their deaths, Patsy Fraser and Harry Fraser were divorced.<br />

Page 9 of 19

WHEREAS, the Final Divorce Decree and Amended Final Divorce Decree, Judgment Roll<br />

Number 24987, indicated that Patsy Fraser would sell her interest in the marital residence located at 6112<br />

Rutledge Hill Road (Richland County TMS No. R168708-07-10) to Harry Fraser for $40,000.<br />

WHEREAS, during their lifetimes Harry Fraser paid Patsy Fraser $40,000 for her interest in the<br />

marital residence.<br />

WHEREAS, Patsy Fraser’s interest in the marital residence was never conveyed to Harry Fraser<br />

during her lifetime.<br />

WHEREAS, <strong>South</strong> <strong>Carolina</strong> Code § 62-3-912 allows competent successors, subject to the rights<br />