Dowbload Part 3 - size: 2.7mb - Screen Africa

Dowbload Part 3 - size: 2.7mb - Screen Africa

Dowbload Part 3 - size: 2.7mb - Screen Africa

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

N<br />

R<br />

INDUSTRY<br />

CR<br />

A<br />

SCREENAFRICA<br />

Y<br />

N<br />

I<br />

V<br />

E<br />

R<br />

S<br />

A<br />

Twenty-one years in the industry<br />

The May 2009 issue of <strong>Screen</strong> <strong>Africa</strong> celebrated our 21st anniversary. Here we<br />

continue the special feature on key players who have been around for a similar<br />

number of years and who have each made a unique contribution to the South <strong>Africa</strong>n<br />

film and television industry.<br />

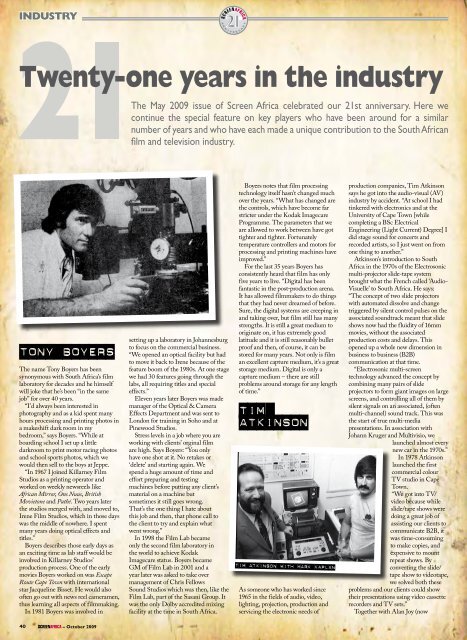

TONY BOYERS<br />

The name Tony Boyers has been<br />

synonymous with South <strong>Africa</strong>’s film<br />

laboratory for decades and he himself<br />

will joke that he’s been “in the same<br />

job” for over 40 years.<br />

“I’d always been interested in<br />

photography and as a kid spent many<br />

hours processing and printing photos in<br />

a makeshift dark room in my<br />

bedroom,” says Boyers. “While at<br />

boarding school I set up a little<br />

darkroom to print motor racing photos<br />

and school sports photos, which we<br />

would then sell to the boys at Jeppe.<br />

“In 1967 I joined Killarney Film<br />

Studios as a printing operator and<br />

worked on weekly newsreels like<br />

<strong>Africa</strong>n Mirror, Ons Nuus, British<br />

Movietone and Pathé. Two years later<br />

the studios merged with, and moved to,<br />

Irene Film Studios, which in those days<br />

was the middle of nowhere. I spent<br />

many years doing optical effects and<br />

titles.”<br />

Boyers describes those early days as<br />

an exciting time as lab staff would be<br />

involved in Killarney Studios’<br />

production process. One of the early<br />

movies Boyers worked on was Escape<br />

Route Cape Town with international<br />

star Jacqueline Bisset. He would also<br />

often go out with news reel cameramen,<br />

thus learning all aspects of filmmaking.<br />

In 1981 Boyers was involved in<br />

setting up a laboratory in Johannesburg<br />

to focus on the commercial business.<br />

“We opened an optical facility but had<br />

to move it back to Irene because of the<br />

feature boom of the 1980s. At one stage<br />

we had 30 features going through the<br />

labs, all requiring titles and special<br />

effects.”<br />

Eleven years later Boyers was made<br />

manager of the Optical & Camera<br />

Effects Department and was sent to<br />

London for training in Soho and at<br />

Pinewood Studios.<br />

Stress levels in a job where you are<br />

working with clients’ orginal film<br />

are high. Says Boyers: “You only<br />

have one shot at it. No retakes or<br />

‘delete’ and starting again. We<br />

spend a huge amount of time and<br />

effort preparing and testing<br />

machines before putting any client’s<br />

material on a machine but<br />

sometimes it still goes wrong.<br />

That’s the one thing I hate about<br />

this job and then, that phone call to<br />

the client to try and explain what<br />

went wrong.”<br />

In 1998 the Film Lab became<br />

only the second film laboratory in<br />

the world to achieve Kodak<br />

Imagecare status. Boyers became<br />

GM of Film Lab in 2001 and a<br />

year later was asked to take over<br />

management of Chris Fellows<br />

Sound Studios which was then, like the<br />

Film Lab, part of the Sasani Group. It<br />

was the only Dolby accredited mixing<br />

facility at the time in South <strong>Africa</strong>.<br />

Boyers notes that film processing<br />

technology itself hasn’t changed much<br />

over the years. “What has changed are<br />

the controls, which have become far<br />

stricter under the Kodak Imagecare<br />

Programme. The parameters that we<br />

are allowed to work between have got<br />

tighter and tighter. Fortunately<br />

temperature controllers and motors for<br />

processing and printing machines have<br />

improved.”<br />

For the last 35 years Boyers has<br />

consistently heard that film has only<br />

five years to live. “Digital has been<br />

fantastic in the post-production arena.<br />

It has allowed filmmakers to do things<br />

that they had never dreamed of before.<br />

Sure, the digital systems are creeping in<br />

and taking over, but film still has many<br />

strengths. It is still a great medium to<br />

originate on, it has extremely good<br />

latitude and it is still reasonably bullet<br />

proof and then, of course, it can be<br />

stored for many years. Not only is film<br />

an excellent capture medium, it’s a great<br />

storage medium. Digital is only a<br />

capture medium – there are still<br />

problems around storage for any length<br />

of time.”<br />

TIM<br />

ATKINSON<br />

Tim Atkinson with Mark Kaplan<br />

As someone who has worked since<br />

1965 in the fields of audio, video,<br />

lighting, projection, production and<br />

servicing the electronic needs of<br />

production companies, Tim Atkinson<br />

says he got into the audio-visual (AV)<br />

industry by accident. “At school I had<br />

tinkered with electronics and at the<br />

University of Cape Town [while<br />

completing a BSc Electrical<br />

Engineering (Light Current) Degree] I<br />

did stage sound for concerts and<br />

recorded artists, so I just went on from<br />

one thing to another.”<br />

Atkinson’s introduction to South<br />

<strong>Africa</strong> in the 1970s of the Electrosonic<br />

multi-projector slide-tape system<br />

brought what the French called ‘Audio-<br />

Visuelle’ to South <strong>Africa</strong>. He says:<br />

“The concept of two slide projectors<br />

with automated dissolve and change<br />

triggered by silent control pulses on the<br />

associated soundtrack meant that slide<br />

shows now had the fluidity of 16mm<br />

movies, without the associated<br />

production costs and delays. This<br />

opened up a whole new dimension in<br />

business to business (B2B)<br />

communication at that time.<br />

“Electrosonic multi-screen<br />

technology advanced the concept by<br />

combining many pairs of slide<br />

projectors to form giant images on large<br />

screens, and controlling all of them by<br />

silent signals on an associated, (often<br />

multi-channel) sound track. This was<br />

the start of true multi-media<br />

presentations. In association with<br />

Johann Kruger and Multivisio, we<br />

launched almost every<br />

new car in the 1970s.”<br />

In 1978 Atkinson<br />

launched the first<br />

commercial colour<br />

TV studio in Cape<br />

Town.<br />

“We got into TV/<br />

video because while<br />

slide/tape shows were<br />

doing a great job of<br />

assisting our clients to<br />

communicate B2B, it<br />

was time-consuming<br />

to make copies, and<br />

expensive to mount<br />

repeat shows. By<br />

converting the slide/<br />

tape show to videotape,<br />

we solved both these<br />

problems and our clients could show<br />

their presentations using video cassette<br />

recorders and TV sets.”<br />

Together with Alan Joy (now<br />

40<br />

SCREENAFRICA – October 2009