Old-New Contract: How to Make Writing Flow - Seattle University

Old-New Contract: How to Make Writing Flow - Seattle University

Old-New Contract: How to Make Writing Flow - Seattle University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

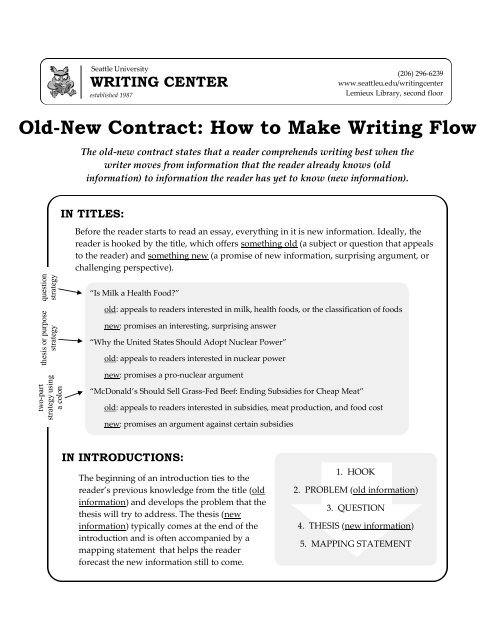

two-part<br />

strategy using<br />

a colon<br />

question<br />

strategy<br />

thesis or purpose<br />

strategy<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

WRITING CENTER<br />

established 1987<br />

(206) 296-6239<br />

www.seattleu.edu/writingcenter<br />

Lemieux Library, second floor<br />

<strong>Old</strong>-<strong>New</strong> <strong>Contract</strong>: <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Make</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Flow</strong><br />

The old-new contract states that a reader comprehends writing best when the<br />

writer moves from information that the reader already knows (old<br />

information) <strong>to</strong> information the reader has yet <strong>to</strong> know (new information).<br />

IN TITLES:<br />

Before the reader starts <strong>to</strong> read an essay, everything in it is new information. Ideally, the<br />

reader is hooked by the title, which offers something old (a subject or question that appeals<br />

<strong>to</strong> the reader) and something new (a promise of new information, surprising argument, or<br />

challenging perspective).<br />

“Is Milk a Health Food?”<br />

old: appeals <strong>to</strong> readers interested in milk, health foods, or the classification of foods<br />

new: promises an interesting, surprising answer<br />

“Why the United States Should Adopt Nuclear Power”<br />

old: appeals <strong>to</strong> readers interested in nuclear power<br />

new: promises a pro-nuclear argument<br />

“McDonald’s Should Sell Grass-Fed Beef: Ending Subsidies for Cheap Meat”<br />

old: appeals <strong>to</strong> readers interested in subsidies, meat production, and food cost<br />

new: promises an argument against certain subsidies<br />

IN INTRODUCTIONS:<br />

The beginning of an introduction ties <strong>to</strong> the<br />

reader’s previous knowledge from the title (old<br />

information) and develops the problem that the<br />

thesis will try <strong>to</strong> address. The thesis (new<br />

information) typically comes at the end of the<br />

introduction and is often accompanied by a<br />

mapping statement that helps the reader<br />

forecast the new information still <strong>to</strong> come.<br />

1. HOOK<br />

2. PROBLEM (old information)<br />

3. QUESTION<br />

4. THESIS (new information)<br />

5. MAPPING STATEMENT

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

WRITING CENTER<br />

established 1987<br />

QUICKTIPS<br />

Transitions<br />

<strong>Old</strong>-new contract can also be practiced on the sentence level by using transitional<br />

words or phrases. Transitions function as signposts, signaling <strong>to</strong> the reader that the<br />

road is turning. (You wouldn’t like for the reader <strong>to</strong> drive off a cliff, would you?)<br />

FUNCTION<br />

WORDS OR PHRASES<br />

<br />

sequence<br />

<br />

first, second, third, next, finally, earlier, later,<br />

meanwhile, afterward<br />

<br />

restatement<br />

<br />

that is, in other words, <strong>to</strong> put it another way<br />

<br />

replacement<br />

<br />

rather, instead<br />

<br />

example<br />

<br />

for example, for instance, case in point<br />

<br />

reason<br />

<br />

because, since, for<br />

<br />

consequence<br />

<br />

therefore, hence, so, consequently, then, as a<br />

result, accordingly, as a consequence<br />

<br />

denied consequence<br />

<br />

still, nevertheless, even so<br />

<br />

concession<br />

<br />

although, even though, granted that<br />

<br />

similarity<br />

<br />

in comparison, likewise, similarly<br />

<br />

contrast<br />

<br />

however, in contrast, conversely, on the other<br />

hand, but, on the contrary<br />

<br />

addition<br />

<br />

in addition, also, moreover, furthermore<br />

<br />

conclusion<br />

<br />

in brief, in sum, in short, in conclusion, <strong>to</strong><br />

sum up, <strong>to</strong> conclude<br />

© <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> Center | Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2012<br />

content adapted from “Teaching <strong>Old</strong>-Before-<strong>New</strong>” by Dr. John Bean<br />

“The Science of Scientific <strong>Writing</strong>” by George Gopen and Judith Swan<br />

* For more tips like these, check out seattleu.edu/writingcenter/resources.