2007 (PDF) - Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science ...

2007 (PDF) - Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science ...

2007 (PDF) - Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Oceans & Human Health<br />

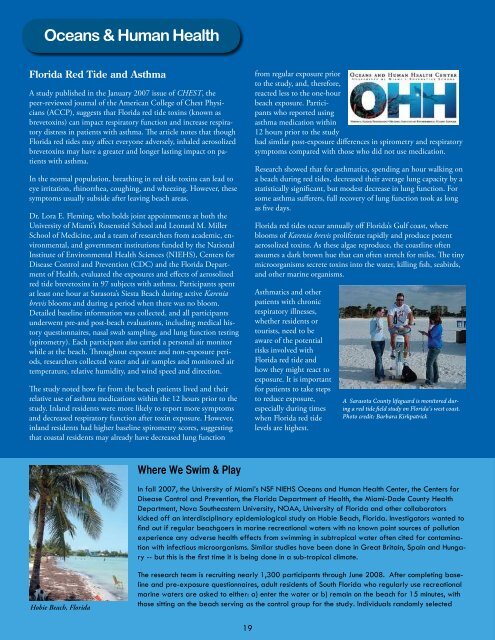

Florida Red Tide <strong>and</strong> Asthma<br />

A study published in the January <strong>2007</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> CHEST, the<br />

peer-reviewed journal <strong>of</strong> the American College <strong>of</strong> Chest Physicians<br />

(ACCP), suggests that Florida red tide toxins (known as<br />

brevetoxins) can impact respiratory function <strong>and</strong> increase respiratory<br />

distress in patients with asthma. The article notes that though<br />

Florida red tides may affect everyone adversely, inhaled aerosolized<br />

brevetoxins may have a greater <strong>and</strong> longer lasting impact on patients<br />

with asthma.<br />

In the normal population, breathing in red tide toxins can lead to<br />

eye irritation, rhinorrhea, coughing, <strong>and</strong> wheezing. However, these<br />

symptoms usually subside after leaving beach areas.<br />

Dr. Lora E. Fleming, who holds joint appointments at both the<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Miami’s <strong>Rosenstiel</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>and</strong> Leonard M. Miller<br />

<strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medicine, <strong>and</strong> a team <strong>of</strong> researchers from academic, environmental,<br />

<strong>and</strong> government institutions funded by the National<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Environmental Health <strong>Science</strong>s (NIEHS), Centers for<br />

Disease Control <strong>and</strong> Prevention (CDC) <strong>and</strong> the Florida Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Health, evaluated the exposures <strong>and</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> aerosolized<br />

red tide brevetoxins in 97 subjects with asthma. Participants spent<br />

at least one hour at Sarasota’s Siesta Beach during active Karenia<br />

brevis blooms <strong>and</strong> during a period when there was no bloom.<br />

Detailed baseline information was collected, <strong>and</strong> all participants<br />

underwent pre-<strong>and</strong> post-beach evaluations, including medical history<br />

questionnaires, nasal swab sampling, <strong>and</strong> lung function testing<br />

(spirometry). Each participant also carried a personal air monitor<br />

while at the beach. Throughout exposure <strong>and</strong> non-exposure periods,<br />

researchers collected water <strong>and</strong> air samples <strong>and</strong> monitored air<br />

temperature, relative humidity, <strong>and</strong> wind speed <strong>and</strong> direction.<br />

The study noted how far from the beach patients lived <strong>and</strong> their<br />

relative use <strong>of</strong> asthma medications within the 12 hours prior to the<br />

study. Inl<strong>and</strong> residents were more likely to report more symptoms<br />

<strong>and</strong> decreased respiratory function after toxin exposure. However,<br />

inl<strong>and</strong> residents had higher baseline spirometry scores, suggesting<br />

that coastal residents may already have decreased lung function<br />

from regular exposure prior<br />

to the study, <strong>and</strong>, therefore,<br />

reacted less to the one-hour<br />

beach exposure. Participants<br />

who reported using<br />

asthma medication within<br />

12 hours prior to the study<br />

had similar post-exposure differences in spirometry <strong>and</strong> respiratory<br />

symptoms compared with those who did not use medication.<br />

Research showed that for asthmatics, spending an hour walking on<br />

a beach during red tides, decreased their average lung capacity by a<br />

statistically significant, but modest decrease in lung function. For<br />

some asthma sufferers, full recovery <strong>of</strong> lung function took as long<br />

as five days.<br />

Florida red tides occur annually <strong>of</strong>f Florida’s Gulf coast, where<br />

blooms <strong>of</strong> Karenia brevis proliferate rapidly <strong>and</strong> produce potent<br />

aerosolized toxins. As these algae reproduce, the coastline <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

assumes a dark brown hue that can <strong>of</strong>ten stretch for miles. The tiny<br />

microorganisms secrete toxins into the water, killing fish, seabirds,<br />

<strong>and</strong> other marine organisms.<br />

Asthmatics <strong>and</strong> other<br />

patients with chronic<br />

respiratory illnesses,<br />

whether residents or<br />

tourists, need to be<br />

aware <strong>of</strong> the potential<br />

risks involved with<br />

Florida red tide <strong>and</strong><br />

how they might react to<br />

exposure. It is important<br />

for patients to take steps<br />

to reduce exposure,<br />

especially during times<br />

when Florida red tide<br />

levels are highest.<br />

A Sarasota County lifeguard is monitored during<br />

a red tide field study on Florida’s west coast.<br />

Photo credit: Barbara Kirkpatrick<br />

Hurricanes & Health<br />

For most, the aftermath <strong>of</strong> a hurricane brings thoughts <strong>of</strong> flattened<br />

homes, uprooted trees, <strong>and</strong> water damage to property left st<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

once the wind <strong>and</strong> rain stop. But it is the dust <strong>and</strong> organic debris<br />

pumped into the area by the strong winds <strong>and</strong> storm surge that<br />

may pack the hardest punch -- the potential for illness <strong>and</strong> even<br />

death – long after the storm has passed.<br />

As part <strong>of</strong> a study assessing urban sediment after Hurricanes Katrina<br />

<strong>and</strong> Rita, scientists from the University <strong>of</strong> Miami published<br />

findings in an April <strong>2007</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> the Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the National<br />

Academy <strong>of</strong> <strong>Science</strong>s, pointing to the need for rapid environmental<br />

assessments as part <strong>of</strong> preventative disaster relief policies. The study,<br />

entitled “Impacts <strong>of</strong> Hurricanes Katrina <strong>and</strong> Rita on the Microbial<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>of</strong> the New Orleans Area,” provided new insights into<br />

the potential for human exposures to both inhaled <strong>and</strong> ingested<br />

pathogens from sewage-contaminated floodwaters generated by<br />

hurricane activity.<br />

Dr. Helena Solo-Gabriele, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Civil <strong>and</strong> Environmental<br />

Engineering at the University <strong>of</strong> Miami <strong>and</strong> co-author <strong>of</strong> the<br />

paper, along<br />

with colleagues<br />

at the NSF/<br />

NIEHS Center<br />

for Oceans <strong>and</strong><br />

Human Health<br />

(OHH) based<br />

at the <strong>Rosenstiel</strong><br />

<strong>School</strong>,<br />

researchers from<br />

five universities,<br />

<strong>and</strong> two other<br />

NSF/NIEHS<br />

Dr. Helena Solo-Gabriele takes a sediment sample in New<br />

Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Photo credit: Brajesh<br />

Dubey<br />

Centers for<br />

OHH, analyzed<br />

water <strong>and</strong> sediment<br />

samples in<br />

New Orleans during the two<br />

months following the 2005<br />

hurricane season. Samples<br />

from the interior canal <strong>and</strong><br />

shoreline <strong>of</strong> New Orleans, <strong>and</strong><br />

the <strong>of</strong>fshore waters <strong>of</strong> Lake<br />

Pontchartrain showed higher<br />

than normal bacteria <strong>and</strong><br />

pathogen levels. The microbial<br />

levels reduced to acceptable<br />

levels within a few weeks after<br />

the intense flooding completely<br />

subsided.<br />

Dried sediment covers the porch <strong>of</strong> a home<br />

after Hurricane Katrina, near New Orleans’<br />

London Street Canal. Photo credit:<br />

Maribeth Gidley<br />

Public health impacts <strong>of</strong><br />

hurricanes vary depending on a number <strong>of</strong> factors. Initial threats<br />

may include drowning due to storm surge or rainfall flooding, with<br />

additional risks from high winds <strong>and</strong> potential tornadoes spawned<br />

by the storm. Emergency response teams face serious public health<br />

risks when attempting rescues, both during <strong>and</strong> after natural disasters.<br />

Findings show the importance <strong>of</strong> a rapid assessment <strong>of</strong> conditions<br />

to protect emergency workers <strong>and</strong> residents from potential<br />

illnesses that could result from exposure.<br />

The 2005 events were characterized by an unusually high volume<br />

<strong>and</strong> long duration <strong>of</strong> human exposure to potentially dangerous<br />

microbes. The most contaminated area tested near the Superdome<br />

contained high levels <strong>of</strong> sewage pathogens. Researchers underscore<br />

the need for improved monitoring efforts that focus on evaluating<br />

the impacts <strong>of</strong> sediments in affected areas, since exposure to contaminated<br />

sediments through inhalation or ingestion, could result<br />

in potential health risks.<br />

Scientists have long been aware that with hurricanes come the<br />

potential for disease, chemical contamination <strong>and</strong> even death. But<br />

concerted efforts are now being undertaken to study <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><br />

the connections between them <strong>and</strong> how at-risk communities<br />

might add another level <strong>of</strong> preparedness to their hurricane preparation<br />

<strong>and</strong> response.<br />

Where We Swim & Play<br />

Hobie Beach, Florida<br />

In fall <strong>2007</strong>, the University <strong>of</strong> Miami’s NSF NIEHS Oceans <strong>and</strong> Human Health Center, the Centers for<br />

Disease Control <strong>and</strong> Prevention, the Florida Department <strong>of</strong> Health, the Miami-Dade County Health<br />

Department, Nova Southeastern University, NOAA, University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>and</strong> other collaborators<br />

kicked <strong>of</strong>f an interdisciplinary epidemiological study on Hobie Beach, Florida. Investigators wanted to<br />

find out if regular beachgoers in marine recreational waters with no known point sources <strong>of</strong> pollution<br />

experience any adverse health effects from swimming in subtropical water <strong>of</strong>ten cited for contamination<br />

with infectious microorganisms. Similar studies have been done in Great Britain, Spain <strong>and</strong> Hungary<br />

-- but this is the first time it is being done in a sub-tropical climate.<br />

The research team is recruiting nearly 1,300 participants through June 2008. After completing baseline<br />

<strong>and</strong> pre-exposure questionnaires, adult residents <strong>of</strong> South Florida who regularly use recreational<br />

marine waters are asked to either: a) enter the water or b) remain on the beach for 15 minutes, with<br />

those sitting on the beach serving as the control group for the study. Individuals r<strong>and</strong>omly selected<br />

to enter the water, submerge their entire body <strong>and</strong> collect a water<br />

sample in a five gallon receptacle for microbial analyses (e.g. bacteria,<br />

viruses, parasites). Researchers then schedule a telephone interview<br />

for a follow up questionnaire about the person’s health to assess<br />

their well being over the seven days after exposure. Ultimately, the<br />

researchers will evaluate if reported health effects are associated<br />

with exposure to non-point source subtropical marine waters, <strong>and</strong> if<br />

the currently recommended microbial assessment methods protect human<br />

health.<br />

Julie Armstrong records pre-study baseline beach characteristics,<br />

such as number <strong>of</strong> people <strong>and</strong> dogs on the beach. Photo credit: Julie<br />

Hollenbeck<br />

19 20

![Wavelength [μm] ZENITH ATMOSPHERIC TRANSMITTANCE](https://img.yumpu.com/26864082/1/190x143/wavelength-i-1-4-m-zenith-atmospheric-transmittance.jpg?quality=85)