Wibbels v. Wibbels - Nebraska Judicial Branch

Wibbels v. Wibbels - Nebraska Judicial Branch

Wibbels v. Wibbels - Nebraska Judicial Branch

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

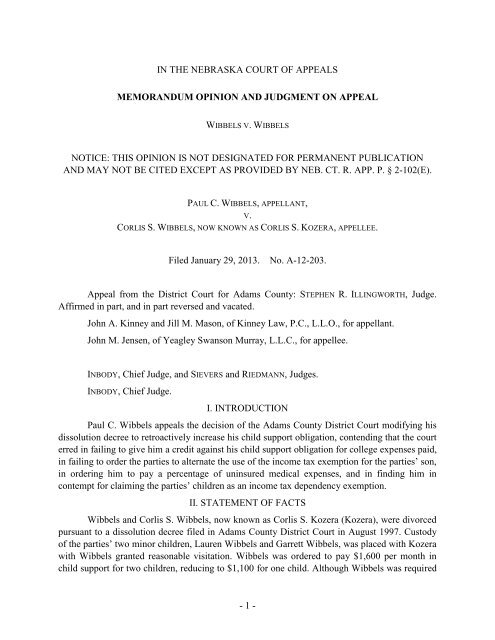

IN THE NEBRASKA COURT OF APPEALS<br />

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND JUDGMENT ON APPEAL<br />

WIBBELS V. WIBBELS<br />

NOTICE: THIS OPINION IS NOT DESIGNATED FOR PERMANENT PUBLICATION<br />

AND MAY NOT BE CITED EXCEPT AS PROVIDED BY NEB. CT. R. APP. P. § 2-102(E).<br />

PAUL C. WIBBELS, APPELLANT,<br />

V.<br />

CORLIS S. WIBBELS, NOW KNOWN AS CORLIS S. KOZERA, APPELLEE.<br />

Filed January 29, 2013.<br />

No. A-12-203.<br />

Appeal from the District Court for Adams County: STEPHEN R. ILLINGWORTH, Judge.<br />

Affirmed in part, and in part reversed and vacated.<br />

John A. Kinney and Jill M. Mason, of Kinney Law, P.C., L.L.O., for appellant.<br />

John M. Jensen, of Yeagley Swanson Murray, L.L.C., for appellee.<br />

INBODY, Chief Judge, and SIEVERS and RIEDMANN, Judges.<br />

INBODY, Chief Judge.<br />

I. INTRODUCTION<br />

Paul C. <strong>Wibbels</strong> appeals the decision of the Adams County District Court modifying his<br />

dissolution decree to retroactively increase his child support obligation, contending that the court<br />

erred in failing to give him a credit against his child support obligation for college expenses paid,<br />

in failing to order the parties to alternate the use of the income tax exemption for the parties’ son,<br />

in ordering him to pay a percentage of uninsured medical expenses, and in finding him in<br />

contempt for claiming the parties’ children as an income tax dependency exemption.<br />

II. STATEMENT OF FACTS<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> and Corlis S. <strong>Wibbels</strong>, now known as Corlis S. Kozera (Kozera), were divorced<br />

pursuant to a dissolution decree filed in Adams County District Court in August 1997. Custody<br />

of the parties’ two minor children, Lauren <strong>Wibbels</strong> and Garrett <strong>Wibbels</strong>, was placed with Kozera<br />

with <strong>Wibbels</strong> granted reasonable visitation. <strong>Wibbels</strong> was ordered to pay $1,600 per month in<br />

child support for two children, reducing to $1,100 for one child. Although <strong>Wibbels</strong> was required<br />

- 1 -

y the decree to provide medical coverage for the children and to pay 85 percent of work-related<br />

daycare expenses, the decree did not include any provisions for uninsured medical expenses, nor<br />

did it address the issue of income tax dependency exemptions for the parties’ minor children.<br />

The decree also provided that <strong>Wibbels</strong> “shall pay the reasonable and necessary expenses<br />

associated with the children obtaining quality college educations.”<br />

In June 2010, Kozera filed a complaint to modify the decree, requesting an increase in<br />

child support and that <strong>Wibbels</strong> be ordered to pay a portion of the minor children’s uninsured<br />

medical expenses. <strong>Wibbels</strong> filed an answer and counterclaim requesting a reduction in his child<br />

support obligation to account for his subsequently born children, requesting that he be awarded<br />

specific parenting time, and requesting that the decree be modified to address the award of<br />

income tax dependency exemptions.<br />

In April 2011, Kozera filed a motion for an order to show cause why <strong>Wibbels</strong> should not<br />

be held in contempt for claiming both of the parties’ children on his 2010 income tax return<br />

despite having knowledge that he was not entitled to claim either of the children for income tax<br />

dependency purposes. The contempt hearing was held on June 7, and the hearing on the<br />

complaint for modification was held on August 18.<br />

1. FINANCIAL CIRCUMSTANCES OF PARTIES<br />

AND LAUREN’S COLLEGE EXPENSES<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> is a physician practicing with Hastings Internal Medicine, P.C., earning a gross<br />

income of approximately $713,000 per year. He is also involved in Hastings Internal Medicine<br />

Building Co., LLC; Hastings Surgical Center, LLC; and Imaging Center of Hastings, LLC.<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> has remarried, and he and his wife have three minor children.<br />

In addition to his medical practice, <strong>Wibbels</strong> invested in an Angus cattle operation, but<br />

due to a genetic defect in the cattle herd, he sustained over $2 million in losses on that<br />

investment. <strong>Wibbels</strong> and his wife signed personal guaranties related to the cattle operation, and<br />

according to <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ testimony, the loans still totaled over $2.4 million, equating to debt<br />

obligations of about $295,000 annually. Additionally, <strong>Wibbels</strong> testified that he has lump-sum<br />

payments related to the debt due in 2014, that are “well over $700,000.” <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ 2010 tax<br />

return showed agricultural losses of $961,676.<br />

Kozera is employed at a clinic in Kearney, earning approximately $58,000 per year. She<br />

has also remarried, and she and her husband have two minor children together. At the time that<br />

Kozera filed the complaint to modify in June 2010, the parties’ oldest child, Lauren, was still a<br />

minor; however, at the time of the hearing in August 2011, Lauren had turned 19. Lauren began<br />

attending college in August 2010, and she turned 19 in March 2011.<br />

Since August 2010, Lauren has not been living in Kozera’s home. During her first<br />

semester of college, Lauren came home about four times, and during her second semester, she<br />

came home about the same amount, perhaps slightly more frequently. Kozera testified that<br />

although Lauren has been attending college since August 2010, she has continued to provide<br />

financial support to Lauren for things such as Lauren’s cellular telephone, car insurance, car<br />

repairs, gas money, uninsured medical expenses, clothes, food, and dormitory room items.<br />

From August 2010 to March 2011, in addition to paying child support for Lauren while<br />

she was attending college, <strong>Wibbels</strong> has paid more than $20,000 in tuition, books, and room and<br />

- 2 -

oard for Lauren to attend college prior to her reaching the age of 19. <strong>Wibbels</strong> testified that he<br />

was requesting a dollar-for-dollar credit to his child support obligation related to Lauren for<br />

paying college tuition and room and board for a child who is under the age of 19 and attending<br />

college. <strong>Wibbels</strong> also testified that he paid $2,000, which was half the cost of Lauren’s car.<br />

2. INCOME TAX DEPENDENCY EXEMPTIONS<br />

The parties acknowledge that the initial dissolution decree did not address the issue of the<br />

income tax dependency exemptions, and the parties likewise acknowledge that <strong>Wibbels</strong> has<br />

claimed the parties’ two children as income tax dependency exemptions every year since 1997.<br />

Kozera testified that the first year, <strong>Wibbels</strong> “bullied” her into giving up the dependency<br />

exemptions, and that she had not pursued the issue since that time until 2011, when she learned<br />

that, as custodial parent, she was entitled to claim the parties’ children for tax purposes since the<br />

dissolution decree did not provide who was to claim the dependency exemptions. She provided<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> with notice that he was not allowed to claim the parties’ children for the 2010 tax year<br />

via letter dated February 17, 2011. Thereafter, <strong>Wibbels</strong> filed a motion with the court to allow<br />

him to claim one of the dependency exemptions and the matter was set for hearing in April, but<br />

no determination was made regarding the issue because <strong>Wibbels</strong> withdrew his motion. Shortly<br />

thereafter, Kozera filed her 2010 tax return and then received notification that the Internal<br />

Revenue Service had rejected her return because <strong>Wibbels</strong> had already filed, claiming the parties’<br />

two children as dependents. Kozera testified that she was required to file an extension to have<br />

her tax forms reprepared and refiled, and in the preparation of the amended return, she learned<br />

that she would receive $5,561 less of a refund without claiming Lauren and Garrett.<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> denied knowing that he did not have the authority to claim the children for<br />

dependency exemptions, testifying that he consulted his attorney and accountant for advice.<br />

When asked by Kozera’s attorney, “You were also informed that you could not, were not,<br />

entitled or not authorized by . . . Kozera to claim the dependency exemptions with respect to the<br />

children for 2010, weren’t you?” <strong>Wibbels</strong> replied, “I was not informed of that, no. I took the<br />

advice of my attorney and the advice of my accountant that I’ve had for several years. I listened<br />

to the wise people that are in my life and I used counsel and did the right thing.” <strong>Wibbels</strong> further<br />

stated that there was never any controversy over him claiming the exemptions and that there was<br />

never any bullying on his part with respect to the dependency exemptions. <strong>Wibbels</strong> proposed that<br />

the parties alternate the dependency exemptions for their children. Kozera also testified that at a<br />

minimum, she would like to receive the exemption for Garrett on an alternating basis.<br />

3. GARRETT’S MEDICAL ISSUES<br />

Kozera testified that Garrett has a medical diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome, which is on<br />

the autism spectrum. Garrett is highly functional, is in a regular classroom at his school,<br />

performs well academically, but does have an individual education plan at school. Garrett has<br />

issues socially and with coordination, and when faced with a new situation, Garrett “just kind of<br />

shuts down.” According to Kozera, Garrett does not feel comfortable interacting socially with<br />

peers or with people with whom he is unfamiliar.<br />

Every year, Kozera takes Garrett to see a doctor in Chicago. This appointment costs<br />

between $700 and $1,000, and the travel expenses associated with the appointment cost another<br />

- 3 -

$1,000, none of which is covered by insurance. According to Kozera, at the doctor’s visit, after<br />

taking information and urine, blood, and hair samples from Garrett, the doctor prescribes<br />

compounded vitamins and minerals for Garrett which cost approximately $250 to $300 per<br />

month. Kozera testified that she has observed a huge improvement in Garrett’s behavior since<br />

undergoing this treatment. According to Kozera, she has used funds from her tax refund to pay<br />

for these expenses because <strong>Wibbels</strong> has not paid for uninsured medical expenses for their<br />

children. <strong>Wibbels</strong> did not acknowledge that Garrett had Asperger’s syndrome, only that he has<br />

some social skills issues.<br />

4. DISTRICT COURT ORDER<br />

In December 2011, the district court entered an order setting <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ monthly child<br />

support at $3,445, which calculation took into account the subsequent children of the parties. The<br />

court rejected <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ argument that application of the guidelines would be unjust or<br />

inappropriate because of the amount of debt that <strong>Wibbels</strong> serviced yearly and the college<br />

expenses that he pays for Lauren, and will be paying for the subsequent children he supports.<br />

The court noted that in 2009 and 2010, <strong>Wibbels</strong> received tax refunds of $166,959 and $217,118,<br />

respectively, and that those refunds were a result of his losses in the cattle business and would<br />

“go a long way in servicing the debt.” Thus, after considering the aforementioned factors, the<br />

district court determined that <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ monthly child support obligation of $3,445 was fair and<br />

equitable.<br />

Further, the district court found that although Kozera requested that <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ increased<br />

child support obligation be retroactive to July 1, 2010, which was the first of the month after she<br />

filed the complaint to modify, the more equitable date to retroactively order support was April 2,<br />

2011, because that was the first of the month after which Lauren emancipated and <strong>Wibbels</strong> had<br />

paid approximately $20,000 for Lauren’s college expenses during the 2010-11 school year. Thus,<br />

the court ordered <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ new child support obligation retroactive to April 2, 2011.<br />

Additionally, the court ordered that effective with the 2011 and subsequent tax years,<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> was allowed to claim Lauren as an exemption pursuant to Department of Treasury<br />

Publication 501, and that Kozera shall receive the exemption for Garrett as the custodial parent<br />

for 2011 and subsequent years.<br />

With regard to the contempt action, the district court made the following factual findings:<br />

that Kozera had allowed <strong>Wibbels</strong> to take the tax exemptions from 1997 until 2009; however, in<br />

2010, when she discovered that as custodial parent, she could take the exemptions, she notified<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> by letter dated February 17, 2011, that he was no longer authorized to claim the parties’<br />

children as dependents for income tax purposes. Kozera filed her 2010 tax return claiming the<br />

minor children as dependents, but her tax return was rejected because <strong>Wibbels</strong> had previously<br />

filed his 2010 tax return claiming the parties’ children as dependents. The rejection of Kozera’s<br />

tax return cost her $5,561 in refunds. The court found that in February 2011, <strong>Wibbels</strong> was put on<br />

notice via letter that he was no longer authorized to claim the parties’ children as dependents for<br />

income tax purposes, that <strong>Wibbels</strong> signed his 2010 tax return on March 29, 2011, and that<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> had filed a request for the court to address the 2010 income tax return but later<br />

withdrew that request on April 14, 2011. Based on these facts and citing the “clear rule” that<br />

absent an agreement between the parties or a court order, the custodial parent gets the exemption,<br />

- 4 -

the court found <strong>Wibbels</strong> in contempt because he was put on notice before filing his return and<br />

held that <strong>Wibbels</strong> could purge his contempt by paying $5,561 to Kozera. The court “entered<br />

judgment” in that amount. This amount was reduced by $1,500 in an order following a motion<br />

for new trial/motion to alter or amend judgment filed by <strong>Wibbels</strong> to reflect the fact that Kozera<br />

claimed an education credit on her tax return summary to which she would not be entitled, which<br />

entry resulted in an overestimation of her estimated tax refund. Thus, the reduced amount of the<br />

judgment was $4,061. Also included in the order on <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ motion for new trial was a<br />

provision that <strong>Wibbels</strong> was responsible for 92 percent of uninsured medical expenses for the<br />

parties’ minor child(ren) after Kozera had paid the first $480 per child per year.<br />

III. ASSIGNMENTS OF ERROR<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> contends that the district court erred in finding him in contempt of court for<br />

claiming the parties’ children as an income tax dependency exemption. He contends that the<br />

district court erred in its modification of the dissolution decree by (a) failing to give him a credit<br />

against his child support obligation for college expenses paid; (b) increasing his monthly child<br />

support obligation to $3,445; (c) ordering the increase in child support retroactive to April 1,<br />

2011; (d) failing to order the parties to alternate the use of the income tax exemption for Garrett;<br />

and (e) ordering him to pay a percentage of uninsured medical expenses.<br />

IV. ANALYSIS<br />

1. CONTEMPT<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> contends that the district court erred in finding him in contempt of court for<br />

claiming the parties’ children as income tax dependency exemptions.<br />

In a civil contempt proceeding where a party seeks remedial relief for an alleged violation<br />

of a court order, an appellate court employs a three-part standard of review in which (1) the trial<br />

court’s resolution of issues of law is reviewed de novo, (2) the trial court’s factual findings are<br />

reviewed for clear error, and (3) the trial court’s determinations of whether a party is in contempt<br />

and of the sanction to be imposed is reviewed for abuse of discretion. Spady v. Spady, 284 Neb.<br />

885, ___ N.W.2d ___ (2012); Hossaini v. Vaelizadeh, 283 Neb. 369, 808 N.W.2d 867 (2012).<br />

When a party to an action fails to comply with a court order made for the benefit of the<br />

opposing party, such act is ordinarily a civil contempt, which requires willful disobedience as an<br />

essential element. Hossaini v. Vaelizadeh, supra. “Willful” means the violation was committed<br />

intentionally, with knowledge that the act violated the court order. Id. Outside of statutory<br />

procedures imposing a different standard, it is the complainant’s burden to prove civil contempt<br />

by clear and convincing evidence. Id.<br />

Because the judicial contempt power is a potent weapon, when founded upon a decree<br />

too vague to be understood, the weapon can be a deadly one. Smeal Fire Apparatus Co. v.<br />

Kreikemeier, 279 Neb. 661, 782 N.W.2d 848 (2010), disapproved on other grounds, Hossaini v.<br />

Vaelizadeh, supra. Thus, those parties who must obey decrees must know what the court intends<br />

to require and what it means to forbid. Id. Understood in light of these principles, the “four<br />

corners” rule for interpreting consent decrees is intended to narrowly construe the circumstances<br />

wherein contempt may be found. Id. Because of the seriousness of the consequences associated<br />

with violation of a court order, courts must read decrees to mean precisely what they say. Id.<br />

- 5 -

Thus, “a court cannot hold a person or party in contempt unless the order or consent decree gave<br />

clear warning that the conduct in question was required or proscribed.” Id. at 700, 782 N.W.2d at<br />

877.<br />

In the instant case, the original dissolution decree did not address the issue of income tax<br />

dependency exemptions. It is well settled that once a decree for dissolution becomes final, its<br />

meaning is determined as a matter of law from the four corners of the decree itself. Blaine v.<br />

Blaine, 275 Neb. 87, 744 N.W.2d 444 (2008). Thus, although a custodial parent is presumptively<br />

entitled to the federal tax exemption for a dependent child, State on behalf of Pathammavong v.<br />

Pathammavong, 268 Neb. 1, 679 N.W.2d 749 (2004), see I.R.C. § 152(e) (2008) and Hall v.<br />

Hall, 238 Neb. 686, 472 N.W.2d 217 (1991), there simply was no court order in place at the time<br />

that <strong>Wibbels</strong> filed his 2010 tax returns which provided that <strong>Wibbels</strong> was not entitled to claim the<br />

minor children as exemptions on his tax return.<br />

Further, the district court held in its journal entry and order entered on December 11,<br />

2011, that “[e]ffective with the 2011 and subsequent tax years [<strong>Wibbels</strong>] may take Lauren as an<br />

exemption pursuant to Department of Treasury Publication 501. [Kozera] shall receive the<br />

exemption on Garrett as the custodial parent for 2011 and subsequent years.” One cannot be held<br />

in contempt of court for acts which became prohibited by a court order entered subsequent to<br />

their commission; a contrary ruling would have the effect of an ex post facto law. Grady v.<br />

Grady, 209 Neb. 311, 307 N.W.2d 780 (1981). See Chicago, B. & Q. R. Co. v. State, 47 Neb.<br />

549, 66 N.W. 624 (1896).<br />

Thus, the district court erred in finding <strong>Wibbels</strong> in contempt for claiming the parties’<br />

children on his 2010 tax return when no prior court order existed addressing the income tax<br />

dependency exemptions. Because of this finding, we also vacate the requirement that <strong>Wibbels</strong><br />

pay Kozera $4,061 in order to purge himself of the contempt.<br />

2. ISSUES RELATED TO MODIFICATION<br />

OF DISSOLUTION DECREE<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> assigns various errors regarding the district court’s order modifying the parties’<br />

dissolution decree.<br />

A party seeking to modify a child support order must show a material change of<br />

circumstances which occurred after the entry of the original decree and which was not<br />

contemplated when the decree was first entered. Sabatka v. Sabatka, 245 Neb. 109, 511 N.W.2d<br />

107 (1994); Phelps v. Phelps, 239 Neb. 618, 477 N.W.2d 552 (1991). Several factors may be<br />

considered in determining whether a material change of circumstances has occurred, including<br />

changes in the financial position of the parent obligated to pay support, the needs of the children<br />

for whom support is paid, good or bad faith motive of the obligated parent in sustaining a<br />

reduction of income, and whether the change is temporary or permanent. Sabatka v. Sabatka,<br />

supra; Dobbins v. Dobbins, 226 Neb. 465, 411 N.W.2d 644 (1987). Modification of a dissolution<br />

decree is a matter entrusted to the discretion of the trial court, whose order is reviewed de novo<br />

on the record, and which will be affirmed absent an abuse of discretion by the trial court. Metcalf<br />

v. Metcalf, 278 Neb. 258, 769 N.W.2d 386 (2009).<br />

- 6 -

(a) Credit Against Child<br />

Support Obligation<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> contends that the district court erred in failing to give him a credit against his<br />

child support obligation for college expenses paid.<br />

The general rule for support overpayment claims is that no credit is given for voluntary<br />

overpayments of child support, even if they are made under a mistaken belief that they are<br />

legally required. Palagi v. Palagi, 10 Neb. App. 231, 627 N.W.2d 765 (2001). See Griess v.<br />

Griess, 9 Neb. App. 105, 608 N.W.2d 217 (2000). However, “‘[e]xceptions are made to the “no<br />

credit for voluntary overpayment rule” when the equities of the circumstances demand it and<br />

when allowing a credit will not work a hardship on the minor children.’” Palagi v. Palagi, 10<br />

Neb. App. at 242, 627 N.W.2d at 774, quoting Griess v. Griess, supra. Whether overpayments of<br />

child support should be credited retroactively against child support payments in arrears is a<br />

question of law. Palagi v. Palagi, supra; Griess v. Griess, supra. There is no evidence or<br />

suggestion that the resolution of this dispute will impact Lauren or cause her hardship; thus, the<br />

question is whether the equities demand that <strong>Wibbels</strong> be given the credit.<br />

In Palagi v. Palagi, supra, this court rejected the father’s request for a child support<br />

credit for college expenses paid for his minor daughter. This court pointed out that the father<br />

knowingly and voluntarily paid the expenses in spite of his ex-wife’s declination to accept those<br />

payments toward the child’s education in lieu of his remaining support obligation. Further, we<br />

noted that the record revealed that the father did not view paying for his daughter’s education as<br />

a burden; rather, he was predisposed to fund her college education and the payments were not a<br />

hardship for him such that the equities demanded that he receive a credit.<br />

In Griess v. Griess, supra, the obligor unwittingly overpaid child support by relying on<br />

inaccurate child support computations calculated by his ex-wife’s attorney; overlooked, ignored,<br />

or implicitly approved by his attorney; and erroneously approved by the trial court. Although the<br />

payments were not “voluntary” or “extra” payments because they were paid in compliance with<br />

the obligation imposed by the court’s flawed order, this court held that equitable relief by<br />

crediting future child support payments was appropriate in that case.<br />

Like the obligor in Griess, <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ college payments were not “voluntary” in that he<br />

was legally obligated to pay “the reasonable and necessary expenses associated with the children<br />

obtaining quality college educations” pursuant to the obligation imposed in the original<br />

dissolution decree. While payment of college expenses is “normally beyond a parent’s legal<br />

obligation,” Palagi v. Palagi, 10 Neb. App. at 242, 627 N.W.2d at 774, in the instant case,<br />

payment of Lauren’s college expenses was exactly that--Wibbel’s legal obligation. Furthermore,<br />

in reviewing the equities of the situation, we find that at the time of the entry of the dissolution<br />

decree, <strong>Wibbels</strong> knew, or should have known, that there was a possibility that Lauren could be<br />

attending college prior to reaching the age of 19 and that, pursuant to the decree, he could be<br />

paying college expenses and child support simultaneously for a period of time. Further, we do<br />

not find any evidence that continuing the payment of his child support obligation for the 7<br />

months from August 2010 until March 2011 constituted a hardship for <strong>Wibbels</strong> such that the<br />

equities demand that he receive credit.<br />

- 7 -

We also reject <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ argument that he should be awarded a credit for 7 months of<br />

child support because, during that period of time, he was paying not only Lauren’s tuition, but<br />

also her health insurance, books, college fees, and her room and board. In support of his<br />

argument, <strong>Wibbels</strong> cites Redfield v. Redfield, 6 Neb. App. 274, 572 N.W.2d 422 (1997), for the<br />

proposition that it is grossly inequitable to allow the custodial parent to receive child support for<br />

a period of time when the children were in the father’s custody and he provided their food and<br />

shelter.<br />

In Redfield v. Redfield, supra, this court affirmed the decision of the district court<br />

granting a father a $6,960 credit toward his child support arrearage for periods of time where the<br />

minor children resided with him and he had provided support by way of food and shelter. A<br />

similar factual situation occurred in Berg v. Berg, 238 Neb. 527, 471 N.W.2d 435 (1991),<br />

wherein the <strong>Nebraska</strong> Supreme Court affirmed a decision granting a father credit against child<br />

support arrearages where the evidence established that two of the children for whom the father<br />

was ordered to pay support lived with him for a definite period of time, during which he directly<br />

provided for their full support.<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> argues that similar to the two aforementioned cases, during the 7 months from<br />

August 2010 to March 2011, when Lauren was enrolled in college as a minor and did not reside<br />

with Kozera, he paid for Lauren’s food and shelter, while Kozera provided no support. Thus, he<br />

claims that like Redfield v. Redfield, supra, it would be grossly inequitable for Kozera to receive<br />

child support for that 7-month time period and equity demands that he be given a child support<br />

credit for that period of time. However, in the instant case, although we acknowledge that<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> was paying for Lauren’s room and board during the time when she was a minor<br />

attending college, we also note that Kozera testified that Lauren came home several times during<br />

that time period and that Kozera continued to provide financial support to Lauren for things such<br />

as Lauren’s cellular telephone, her car insurance, car repairs, gas money, uncovered medical<br />

expenses, clothes, food, and items for Lauren’s dormitory room. Because Kozera continued to<br />

provide support to Lauren during the time period that she was a minor attending college and<br />

because <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ paying 7 months of child support during the time when he was also paying<br />

Lauren’s college expenses does not represent a significant financial hardship for him, we reject<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong>’ argument and find that the district court did not abuse its discretion in failing to give<br />

him a credit against his child support obligation for college expenses paid.<br />

(b) Amount of Child Support<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> further contends that the district court erred in increasing his monthly child<br />

support obligation to $3,445. He concedes that his child support obligation should be increased<br />

to $2,200 per month as a rebuttable presumption pursuant to the <strong>Nebraska</strong> Child Support<br />

Guidelines; however, he contends that the trial court abused its discretion in failing to consider<br />

his debt obligation and his contributions to his children’s college education in determining the<br />

amount of his obligation above the rebuttable presumption.<br />

The paramount concern and question in determining child support, whether in the initial<br />

marital dissolution action or in the proceedings for modification of decree, is the best interests of<br />

the child. Gangwish v. Gangwish, 267 Neb. 901, 678 N.W.2d 503 (2004); Hendrix v. Sivick, 19<br />

Neb. App. 140, 803 N.W.2d 525 (2011). The support of one’s children is a fundamental<br />

- 8 -

obligation which takes precedence over almost everything else. Gangwish v. Gangwish, supra;<br />

Hendrix v. Sivick, supra. The primary consideration in determining the level of child support<br />

payments is the best interests of the child. Sabatka v. Sabatka, 245 Neb. 109, 511 N.W.2d 107<br />

(1994); Phelps v. Phelps, 239 Neb. 618, 477 N.W.2d 552 (1991); Schulze v. Schulze, 238 Neb.<br />

81, 469 N.W.2d 139 (1991).<br />

Pursuant to <strong>Nebraska</strong> Child Support Guidelines § 4-203 (rev. 2011):<br />

The child support guidelines shall be applied as a rebuttable presumption. All<br />

orders for child support obligations shall be established in accordance with the provisions<br />

of the guidelines unless the court finds that one or both parties have produced sufficient<br />

evidence to rebut the presumption that the guidelines should be applied. . . . Deviations<br />

must take into consideration the best interests of the child. In the event of a deviation, the<br />

reason for the deviation shall be contained in the findings portion of the decree or order,<br />

or worksheet 5 should be completed by the court and filed in the court file. Deviations<br />

from the guidelines are permissible under the following circumstances:<br />

. . . .<br />

(C) [I]f total net income exceeds $15,000 monthly, child support for amounts in<br />

excess of $15,000 monthly may be more but shall not be less than the amount which<br />

would be computed using the $15,000 monthly income unless other permissible<br />

deviations exist. To assist the court and not as a rebuttable presumption, the court may<br />

use the amount at $15,000 plus: 10 percent of net income above $15,000 for one, two,<br />

and three children . . . .<br />

Although farming losses are generally figured in arriving at the total monthly income<br />

considered in the guidelines, income for the purpose of child support is not synonymous with<br />

taxable income, and therefore even if a party is entitled to take a loss from taxable income due to<br />

farming losses, it does not necessarily follow that the loss is also considered for the purpose of<br />

calculating a child support obligation. Rauch v. Rauch, 256 Neb. 257, 590 N.W.2d 170 (1999).<br />

The record establishes that <strong>Wibbels</strong> has claimed a loss for his taxable income, he<br />

assumed the risk inherent in the investment in the cattle operation, and, as the district court<br />

determined, <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ income allows him to service the debt in addition to meeting his child<br />

support obligations. Lowering <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ child support obligation on the basis of these business<br />

losses is not in his minor children’s best interests and the district court did not abuse its<br />

discretion in failing to lower his child support obligation due to those losses. Further, the district<br />

court did not abuse its discretion in failing to lower <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ child support obligation based upon<br />

his obligation to fund his children’s college educations because a deviation on this basis is not in<br />

the minor children’s best interests and, as we found earlier in this opinion, payment of the minor<br />

children’s college expenses does not represent a significant financial hardship for <strong>Wibbels</strong>. Thus,<br />

we affirm <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ child support obligation as determined by the district court.<br />

(c) Retroactive Child Support Increase<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> also contends that the district court abused its discretion in ordering the increase<br />

in his child support obligation retroactive to April 1, 2011.<br />

- 9 -

Whether a child support order should be retroactive is entrusted to the discretion of the<br />

trial court and will be affirmed absent an abuse of discretion. Emery v. Moffett, 269 Neb. 867,<br />

697 N.W.2d 249 (2005).<br />

“‘[A]bsent equities to the contrary, the modification of child support orders should be<br />

applied retroactively to the first day of the month following the filing date of the application for<br />

modification.’” Lucero v. Lucero, 16 Neb. App. 706, 716, 750 N.W.2d 377, 386 (2008), quoting<br />

Theisen v. Theisen, 14 Neb. App. 441, 708 N.W.2d 847 (2006). In determining whether a parent<br />

should be ordered to pay retroactive support in a modification proceeding, the court must<br />

consider “‘the status, character, and situation of the parties and attendant circumstances,<br />

including the financial condition of the parties and the estimated cost of support of the<br />

children,’” as well as the obligated party’s ability to pay the lump sum that will necessarily result<br />

by the entry of such a retroactive order. Cooper v. Cooper, 8 Neb. App. 532, 537-38, 598<br />

N.W.2d 474, 478 (1999). See, also, Wilkins v. Wilkins, 269 Neb. 937, 697 N.W.2d 280 (2005)<br />

(applying our standard in Cooper v. Cooper, supra); Lucero v. Lucero, supra (applying our<br />

standard in Cooper v. Cooper, supra).<br />

The district court ordered <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ child support retroactive to April 1, 2011, which was<br />

the first of the month after Lauren’s emancipation. In making its determination, the court noted<br />

that Kozera had requested that <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ increased child support obligation be retroactive to July<br />

1, 2010, which was the first of the month after she filed the complaint to modify; however, the<br />

court took into account the fact that <strong>Wibbels</strong> had paid approximately $20,000 for Lauren’s<br />

college expenses during the 2010-11 school year prior to her emancipation. There was abundant<br />

evidence adduced regarding <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ income, and the evidence shows that his income is<br />

sufficient to meet his obligation to pay the retroactive child support and still meet his current<br />

obligations. Thus, the district court’s decision to order <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ child support increase to be<br />

retroactive to April 1, 2011, did not constitute an abuse of discretion.<br />

(d) Income Tax Dependency Exemptions<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> contends that the district court erred in failing to order the parties to alternate the<br />

use of the income tax dependency exemption for the parties’ minor son, Garrett. He argues that<br />

Garrett was 16 years old at the time of trial and that in approximately 2 years, he would most<br />

likely be attending college with <strong>Wibbels</strong> solely responsible for Garrett’s college expenses, at<br />

which time he should be allowed to claim Garrett as a dependency exemption on at least an<br />

alternating basis.<br />

The general rule is that a custodial parent is presumptively entitled to the federal tax<br />

exemption for a dependent child. Emery v. Moffett, 269 Neb. 867, 697 N.W.2d 249 (2005). See,<br />

I.R.C. § 152(e) (2008); Hall v. Hall, 238 Neb. 686, 472 N.W.2d 217 (1991). However, a court<br />

may exercise its equitable powers to allocate the exemption to a noncustodial parent. Emery v.<br />

Moffett, supra; Hall v. Hall, supra. An award of a dependency exemption is reviewed de novo to<br />

determine whether the trial court abused its discretion. Emery v. Moffett, supra (court’s decision<br />

in modification declining to change award of dependency exemption from custodial parent to<br />

noncustodial parent was not abuse of trial court’s discretion). See, also, Pope v. Pope, 251 Neb.<br />

773, 559 N.W.2d 192 (1997).<br />

- 10 -

It is undisputed that the original dissolution decree did not allocate the tax dependency<br />

exemptions for the parties’ minor children. It is likewise undisputed that <strong>Wibbels</strong> has claimed the<br />

tax dependency exemptions for both children from 1997 until 2009 and that in February 2010,<br />

Kozera informed him that he was to no longer claim the tax dependency exemptions for both<br />

children. The district court ordered that in 2011 and subsequent tax years, <strong>Wibbels</strong> was allowed<br />

to claim Lauren as a tax dependency exemption, and that Kozera shall receive the exemption for<br />

Garrett as the custodial parent for 2011 and subsequent years. Based on our de novo review of<br />

the record, and noting that <strong>Wibbels</strong> has had the benefit of both tax dependency exemptions since<br />

1997, we cannot say that the district court abused its discretion in awarding the tax dependency<br />

exemptions as it did.<br />

(e) Uninsured Medical Expenses<br />

<strong>Wibbels</strong> contends that the district court erred in modifying the dissolution decree to order<br />

him to pay a percentage of Garrett’s uninsured medical expenses when the original decree did<br />

not require him to pay a portion of the uninsured medical expenses and there was no evidence of<br />

a material change of circumstances warranting such an award.<br />

A decree for child support in a divorce case is always subject to review and modification<br />

regardless of the particular language of the award. Hoover v. Hoover, 2 Neb. App. 239, 508<br />

N.W.2d 316 (1993). Regarding minor children, a dissolution decree is never final in the sense<br />

that it cannot be changed. Id.<br />

The responsibility of a minor child’s parent to pay uninsured medical expenses has been<br />

addressed by both the <strong>Nebraska</strong> Supreme Court and this court. The <strong>Nebraska</strong> Supreme Court in<br />

Druba v. Druba, 238 Neb. 279, 284, 470 N.W.2d 176, 180 (1991), held that “[b]oth parents have<br />

the duty to support their minor children” and that “the children’s need for future and necessary<br />

medical services may not be ignored by either parent.” Similarly, in Hendrix v. Sivick, 19 Neb.<br />

App. 140, 146, 803 N.W.2d 525, 531 (2011), this court held that “[i]t is in the best interests of<br />

the child for each parent to pay his or her proportionate share of the child’s childcare and<br />

uninsured medical expenses.”<br />

In 1997, when the parties’ original dissolution decree was filed, the <strong>Nebraska</strong> Child<br />

Support Guidelines provided that “the court may apportion all nonreimbursed children’s health<br />

care costs between the parents according to the same formula used to determine each parent’s<br />

share of support.” <strong>Nebraska</strong> Child Support Guidelines, paragraph O (amended in 1996).<br />

However, in the interim, the <strong>Nebraska</strong> Child Support Guidelines were amended. In June 2010,<br />

when Kozera filed the complaint to modify the parties’ dissolution decree, the guidelines<br />

provided that “[a]ll nonreimbursed reasonable and necessary children’s health care costs in<br />

excess of $480 per child per year shall be allocated to the obligor parent as determined by the<br />

court, but shall not exceed the proportion of the obligor’s parental contribution (worksheet 1, line<br />

6).” <strong>Nebraska</strong> Child Support Guidelines § 4-215(B) (rev. 2009). This change is a material change<br />

of circumstances since the entry of the dissolution decree.<br />

The evidence established that Garrett has a medical condition requiring medical attention<br />

resulting in uninsured medical expenses. It is both parents’ responsibility to pay their<br />

proportionate share of their minor children’s uninsured medical expenses. Thus, the district court<br />

- 11 -

did not abuse its discretion in ordering <strong>Wibbels</strong> to pay his proportionate share of 92 percent of<br />

the minor children’s uninsured medical expenses.<br />

V. CONCLUSION<br />

Having considered <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ assigned errors regarding the modification and rejected<br />

them, we affirm the modification order, including the provisions regarding uninsured medical<br />

expenses contained in the court’s order following <strong>Wibbels</strong>’ motion for a new trial. However,<br />

having found that the district court erred in finding <strong>Wibbels</strong> in contempt for claiming the parties’<br />

children on his 2010 tax return when no prior court order existed addressing the income tax<br />

dependency exemptions, we reverse the order of contempt. Because of this finding, we also<br />

vacate the requirement that <strong>Wibbels</strong> pay Kozera $4,061 in order to purge himself of the<br />

contempt.<br />

AFFIRMED IN PART, AND IN PART<br />

REVERSED AND VACATED.<br />

- 12 -