Barrett's Esophagus in Females - USC Department of Surgery ...

Barrett's Esophagus in Females - USC Department of Surgery ...

Barrett's Esophagus in Females - USC Department of Surgery ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

American Journal <strong>of</strong> Gastroenterology ISSN 0002-9270<br />

C○ 2005 by Am. Coll. <strong>of</strong> Gastroenterology<br />

doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40962.x<br />

Published by Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g<br />

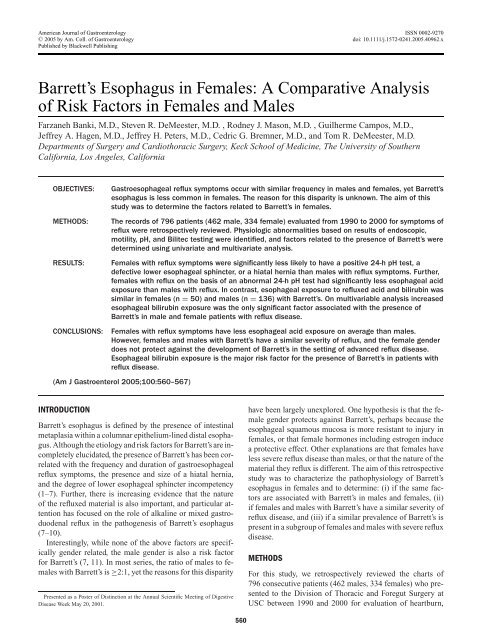

Barrett’s <strong>Esophagus</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Females</strong>: A Comparative Analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong> Risk Factors <strong>in</strong> <strong>Females</strong> and Males<br />

Farzaneh Banki, M.D., Steven R. DeMeester, M.D. , Rodney J. Mason, M.D. , Guilherme Campos, M.D.,<br />

Jeffrey A. Hagen, M.D., Jeffrey H. Peters, M.D., Cedric G. Bremner, M.D., and Tom R. DeMeester, M.D.<br />

<strong>Department</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Surgery</strong> and Cardiothoracic <strong>Surgery</strong>, Keck School <strong>of</strong> Medic<strong>in</strong>e, The University <strong>of</strong> Southern<br />

California, Los Angeles, California<br />

OBJECTIVES:<br />

METHODS:<br />

RESULTS:<br />

CONCLUSIONS:<br />

Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms occur with similar frequency <strong>in</strong> males and females, yet Barrett’s<br />

esophagus is less common <strong>in</strong> females. The reason for this disparity is unknown. The aim <strong>of</strong> this<br />

study was to determ<strong>in</strong>e the factors related to Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> females.<br />

The records <strong>of</strong> 796 patients (462 male, 334 female) evaluated from 1990 to 2000 for symptoms <strong>of</strong><br />

reflux were retrospectively reviewed. Physiologic abnormalities based on results <strong>of</strong> endoscopic,<br />

motility, pH, and Bilitec test<strong>in</strong>g were identified, and factors related to the presence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s were<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed us<strong>in</strong>g univariate and multivariate analysis.<br />

<strong>Females</strong> with reflux symptoms were significantly less likely to have a positive 24-h pH test, a<br />

defective lower esophageal sph<strong>in</strong>cter, or a hiatal hernia than males with reflux symptoms. Further,<br />

females with reflux on the basis <strong>of</strong> an abnormal 24-h pH test had significantly less esophageal acid<br />

exposure than males with reflux. In contrast, esophageal exposure to refluxed acid and bilirub<strong>in</strong> was<br />

similar <strong>in</strong> females (n = 50) and males (n = 136) with Barrett’s. On multivariable analysis <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

esophageal bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure was the only significant factor associated with the presence <strong>of</strong><br />

Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> male and female patients with reflux disease.<br />

<strong>Females</strong> with reflux symptoms have less esophageal acid exposure on average than males.<br />

However, females and males with Barrett’s have a similar severity <strong>of</strong> reflux, and the female gender<br />

does not protect aga<strong>in</strong>st the development <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> the sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> advanced reflux disease.<br />

Esophageal bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure is the major risk factor for the presence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> patients with<br />

reflux disease.<br />

(Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:560–567)<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Barrett’s esophagus is def<strong>in</strong>ed by the presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al<br />

metaplasia with<strong>in</strong> a columnar epithelium-l<strong>in</strong>ed distal esophagus.<br />

Although the etiology and risk factors for Barrett’s are <strong>in</strong>completely<br />

elucidated, the presence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s has been correlated<br />

with the frequency and duration <strong>of</strong> gastroesophageal<br />

reflux symptoms, the presence and size <strong>of</strong> a hiatal hernia,<br />

and the degree <strong>of</strong> lower esophageal sph<strong>in</strong>cter <strong>in</strong>competency<br />

(1–7). Further, there is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g evidence that the nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> the refluxed material is also important, and particular attention<br />

has focused on the role <strong>of</strong> alkal<strong>in</strong>e or mixed gastroduodenal<br />

reflux <strong>in</strong> the pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s esophagus<br />

(7–10).<br />

Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, while none <strong>of</strong> the above factors are specifically<br />

gender related, the male gender is also a risk factor<br />

for Barrett’s (7, 11). In most series, the ratio <strong>of</strong> males to females<br />

with Barrett’s is ≥2:1, yet the reasons for this disparity<br />

Presented as a Poster <strong>of</strong> Dist<strong>in</strong>ction at the Annual Scientific Meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Digestive<br />

Disease Week May 20, 2001.<br />

have been largely unexplored. One hypothesis is that the female<br />

gender protects aga<strong>in</strong>st Barrett’s, perhaps because the<br />

esophageal squamous mucosa is more resistant to <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong><br />

females, or that female hormones <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g estrogen <strong>in</strong>duce<br />

a protective effect. Other explanations are that females have<br />

less severe reflux disease than males, or that the nature <strong>of</strong> the<br />

material they reflux is different. The aim <strong>of</strong> this retrospective<br />

study was to characterize the pathophysiology <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s<br />

esophagus <strong>in</strong> females and to determ<strong>in</strong>e: (i) if the same factors<br />

are associated with Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> males and females, (ii)<br />

if females and males with Barrett’s have a similar severity <strong>of</strong><br />

reflux disease, and (iii) if a similar prevalence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s is<br />

present <strong>in</strong> a subgroup <strong>of</strong> females and males with severe reflux<br />

disease.<br />

METHODS<br />

For this study, we retrospectively reviewed the charts <strong>of</strong><br />

796 consecutive patients (462 males, 334 females) who presented<br />

to the Division <strong>of</strong> Thoracic and Foregut <strong>Surgery</strong> at<br />

<strong>USC</strong> between 1990 and 2000 for evaluation <strong>of</strong> heartburn,<br />

560

Comparative Analysis <strong>of</strong> Risk Factors <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>Esophagus</strong> 561<br />

regurgitation, dysphagia, or a comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> reflux symptoms.<br />

Information about the nature and duration <strong>of</strong> the patients<br />

symptoms was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from review <strong>of</strong> the detailed<br />

history taken at the time <strong>of</strong> presentation <strong>of</strong> the patient to one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the authors, and is based on the patient’s best recollection.<br />

This study was approved by the IRB <strong>of</strong> the University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Southern California.<br />

Def<strong>in</strong>itions<br />

Barrett’s esophagus was def<strong>in</strong>ed as any endoscopically visible<br />

length <strong>of</strong> columnar epithelium above the gastroesophageal<br />

junction (GEJ) with <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al metaplasia on biopsy. This def<strong>in</strong>ition<br />

excluded all patients with a normal upper endoscopy<br />

and <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al metaplasia at the GEJ on biopsy (<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al<br />

metaplasia <strong>of</strong> the cardia), as well as those with a non<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>alized<br />

columnar-l<strong>in</strong>ed distal esophagus. Long-segment Barrett’s<br />

was def<strong>in</strong>ed as a length <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s ≥3 cm.<br />

Upper GI Endoscopy<br />

Upper endoscopy was performed <strong>in</strong> all patients, and biopsies<br />

were obta<strong>in</strong>ed us<strong>in</strong>g large-capacity biopsy forceps (Microvasive<br />

® radial jaw 31263-20 or 1597-20). The GEJ was def<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

as the location where, with the stomach decompressed, the<br />

proximal extent <strong>of</strong> the gastric rugal folds jo<strong>in</strong>ed the tubular<br />

esophagus. The location <strong>of</strong> the GEJ, the squamocolumnar<br />

junction (SCJ), and the crural impression were carefully<br />

noted <strong>in</strong> each patient. A hiatal hernia was diagnosed when<br />

the GEJ was located ≥2 cmabove the crural impression. In<br />

all patients biopsies were obta<strong>in</strong>ed antegrade and retr<strong>of</strong>lexed<br />

from the GEJ, from the gastric antrum and fundus, and from<br />

4-quadrants every 2 cm start<strong>in</strong>g at the GEJ and go<strong>in</strong>g up<br />

to the SCJ <strong>in</strong> patients with a columnar segment extend<strong>in</strong>g<br />

proximally <strong>in</strong>to the esophagus.<br />

Manometry Technique<br />

Esophageal manometry was performed with an eight-channel<br />

water perfused catheter us<strong>in</strong>g a standard station pull-through<br />

technique as previously described (12). The lower esophageal<br />

sph<strong>in</strong>cter (LES) was classified as manometrically defective<br />

on the basis <strong>of</strong> one or more <strong>of</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g: a rest<strong>in</strong>g pressure<br />

<strong>of</strong> less than 6 mmHg, an overall length <strong>of</strong> less than 2 cm, and<br />

/or an abdom<strong>in</strong>al length <strong>of</strong> less than 1 cm.<br />

Ambulatory Esophageal pH Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Technique<br />

Ambulatory measurement <strong>of</strong> esophageal acid exposure was<br />

performed over a 24-h period with a pH probe placed 5 cm<br />

above the upper border <strong>of</strong> the manometrically determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

LES. Acid-suppress<strong>in</strong>g medications were discont<strong>in</strong>ued before<br />

test<strong>in</strong>g (2 wk for proton pump <strong>in</strong>hibitors, 2 days for<br />

H 2 blockers). A commercially available s<strong>of</strong>tware program<br />

(Synectics Medical, M<strong>in</strong>neapolis, MN) was used to analyze<br />

the trac<strong>in</strong>g. Increased (abnormal) esophageal acid exposure<br />

was def<strong>in</strong>ed as a total time pH < 4greater than 4.4%.<br />

Ambulatory Esophageal Bilirub<strong>in</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Technique<br />

Bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure was determ<strong>in</strong>ed over a 24-h period us<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

Bilitec ® probe (Bilitec 2000, Medtronic Inc., Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al<br />

Division, M<strong>in</strong>neapolis, MN) placed 5 cm above the upper border<br />

<strong>of</strong> the manometrically determ<strong>in</strong>ed LES. Acid-suppress<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and antacid medications were discont<strong>in</strong>ued 48 h before test<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

and patients were <strong>in</strong>structed to follow a specific diet that<br />

excluded food that would <strong>in</strong>terfere with the probe’s function<br />

as previously described (13). A commercially available s<strong>of</strong>tware<br />

program was used to analyze the trac<strong>in</strong>g (Bilitec 2000,<br />

Synectics Medical, Dallas, TX). An absorbance threshold <strong>of</strong><br />

0.2 was used, and <strong>in</strong>creased (abnormal) esophageal bilirub<strong>in</strong><br />

exposure was def<strong>in</strong>ed as an exposure >2.2% for the 24-h period.<br />

Measurement <strong>of</strong> esophageal bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure with the<br />

Bilitec probe was used as a surrogate for alkal<strong>in</strong>e or duodenogastro-esophageal<br />

reflux.<br />

Pathology<br />

Biopsy specimens were fixed <strong>in</strong> 10% formaldehyde, embedded<br />

<strong>in</strong> paraff<strong>in</strong>, sectioned, mounted on slides, and sta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

with hematoxyl<strong>in</strong> and eos<strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g standard techniques. A<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle expert GI pathologist <strong>in</strong>terpreted all slides. Specialized<br />

<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al metaplasia was determ<strong>in</strong>ed by the presence <strong>of</strong><br />

well-def<strong>in</strong>ed goblet cells on rout<strong>in</strong>e sections, and confirmed<br />

<strong>in</strong> select cases by positive sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g with Alcian blue at pH<br />

2.5. Giemsa sta<strong>in</strong>ed antral biopsies were used to determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

the presence <strong>of</strong> H. pylori <strong>in</strong>fection.<br />

Statistics<br />

Data are reported as median and <strong>in</strong>terquartile range unless<br />

otherwise specified. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical<br />

data while cont<strong>in</strong>uous variables were analyzed us<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

Mann-Whitney test. Factors potentially predictive <strong>of</strong> the presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> Barrett’s esophagus <strong>in</strong> patients proven to have reflux<br />

disease on the basis <strong>of</strong> an abnormal 24-h pH test were assessed<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g univariate analysis and <strong>in</strong>cluded age, body mass<br />

<strong>in</strong>dex (BMI), the duration <strong>of</strong> symptoms, presence <strong>of</strong> hiatal<br />

hernia, number <strong>of</strong> reflux episodes, number <strong>of</strong> reflux episodes<br />

last<strong>in</strong>g greater than 5 m<strong>in</strong>, longest reflux episode, presence <strong>of</strong><br />

a defective LES, and bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure. Significant factors<br />

were then entered <strong>in</strong>to a multivariable model as <strong>in</strong>dependent<br />

parameters. Forward stepwise logistic regression was performed<br />

to assess the jo<strong>in</strong>t effect <strong>of</strong> the variables and to def<strong>in</strong>e<br />

those that were <strong>in</strong>dependently associated with the presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> Barrett’s esophagus <strong>in</strong> females and <strong>in</strong> males. The results<br />

are presented as adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence<br />

limits (CL) and p-values from the adjusted Wald’s<br />

test. The Wald test was computed <strong>in</strong> SPSS (Version 10) us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the square <strong>of</strong> the coefficient divided by the standard error for<br />

the <strong>in</strong>dependent variables. All analyses were two-sided with<br />

significance set at 0.05 (α = 0.05).<br />

RESULTS<br />

Entire Population<br />

The characteristics <strong>of</strong> the entire population are shown <strong>in</strong><br />

Table 1.<strong>Females</strong> evaluated for reflux symptoms were older<br />

and significantly less likely to have a positive 24-h pH test, a

562 Banki et al.<br />

Table 1. Characteristics <strong>of</strong> the Study Population<br />

Whole Population <strong>Females</strong> Males p-Value ‡<br />

n 796 334 (42%) 462 (58%)<br />

Age (years) 52 (43–64) 54 (44–67) 51(42–62.5) 0.02<br />

BMI ∗ (kg/m 2 ) 26.4 (23.6–29.5) 26.7 (22.5–30.8) 26.2 (23.8–28.9) 0.552<br />

DOS † (years) 6 (3–14) 6 (3–11) 6 (3–15) 0.285<br />

Number <strong>of</strong> patients with 24-h pH monitor<strong>in</strong>g 769 (97%) 308 (92%) 461 (99%)<br />

Abnormal 24-h pH 506 (66%) 165 (49%) 341 (74%) 0.0001<br />

Number <strong>of</strong> patients with manometry 776 (98%) 315 (94%) 461 (99%)<br />

Patients with defective LES 507 (65%) 185 (59%) 322 (70%) 0.002<br />

Number <strong>of</strong> patients with Bilitec probe 345 (43%) 132 (49%) 213 (46%)<br />

Abnormal Bilitec probe 164 (48%) 57 (43%) 107 (50%) 0.223<br />

Prevalence <strong>of</strong> hiatal hernia 441 (56%) 160 (48%) 281 (61%) 0.0003<br />

Prevalence <strong>of</strong> H. pylori # 57 (12%) 18 (12.5%) 39 (11%) 0.74<br />

Prevalence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s 209 (26%) 63 (18%) 146 (32%) 0.001<br />

Values are medians, (<strong>in</strong>terquartile range) or (%).<br />

∗ BMI: body mass <strong>in</strong>dex.<br />

† DOS: Duration <strong>of</strong> symptoms.<br />

‡ <strong>Females</strong> versus males.<br />

# Information on H. pylori status was available for 484 patients; 144 females and 340 males.<br />

defective LES, or a hiatal hernia than males evaluated for reflux<br />

symptoms dur<strong>in</strong>g the same time period. Barrett’s esophagus<br />

was present <strong>in</strong> 26% <strong>of</strong> the entire group, and was significantly<br />

more prevalent <strong>in</strong> males. From the 796 patients<br />

evaluated for reflux 263 patients were found to have normal<br />

esophageal acid exposure by 24-h pH monitor<strong>in</strong>g, and<br />

27 patients did not have a pH test. These 240 patients were<br />

excluded from further analysis.<br />

Comparison <strong>of</strong> <strong>Females</strong> and Males with Increased<br />

Esophageal Acid Exposure<br />

The characteristics <strong>of</strong> the 506 patients with <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

esophageal acid exposure on 24-h pH monitor<strong>in</strong>g are shown<br />

<strong>in</strong> Table 2. Compared to males, females with reflux disease<br />

were significantly older, had a greater body mass <strong>in</strong>dex, and<br />

had less esophageal acid exposure. Barrett’s esophagus was<br />

present <strong>in</strong> 37% <strong>of</strong> patients with an abnormal 24-h pH test,<br />

and was significantly more prevalent <strong>in</strong> males. Long-segment<br />

Barrett’s was more common <strong>in</strong> males while short-segment<br />

Barrett’s predom<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> females. Compared to patients with<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased esophageal acid exposure but without Barrett’s, females<br />

and males with Barrett’s had significantly greater reflux<br />

<strong>of</strong> both acid and bilirub<strong>in</strong> (Figs. 1A, B), and were significantly<br />

more likely to have a positive Bilitec test (Table 3). There was<br />

no difference <strong>in</strong> the prevalence <strong>of</strong> an abnormal Bilitec test<br />

between females and males without Barrett’s (p = 0.6), nor<br />

between females and males with Barrett’s (p = 0.2). Lastly,<br />

we found that the overall length and pressure <strong>of</strong> the LES as<br />

well as the prevalence <strong>of</strong> a defective LES was significantly<br />

different <strong>in</strong> patients with and without Barrett’s (Table 4).<br />

Comparison <strong>of</strong> <strong>Females</strong> and Males with Barrett’s<br />

We found that females and males with Barrett’s were remarkably<br />

similar. <strong>Females</strong> with Barrett’s were older (median 57<br />

vs 52 yr, p = 0.049), while males had a longer duration <strong>of</strong><br />

symptoms (12 vs 10 yr, p = 0.049), but the differences were<br />

Table 2. Characteristics <strong>of</strong> the Population with Abnormal 24-h pH Test<br />

Whole Population <strong>Females</strong> Males p-Value †<br />

n 506 165 (33%) 341 (67%)<br />

Age (years) 53 (44–64) 56 (47–67) 51(42–61) 0.0006<br />

BMI ∗ (kg/m 2 ) 27.2 (24–30) 28.4 (26–33) 26.6 (24–29) 0.004<br />

DOS ‡ (years) 8 (3–16) 9 (3–13) 7 (3–17) 0.981<br />

Total % time pH < 4 9.6 (6.8–15.9) 9.2 (6.3–14.7) 10.3 (6.9–16.1) 0.03<br />

Total % time bilirub<strong>in</strong> 6.0 (0.3–23.2) 4.2 (0.1–15.9) 7.7 (0.4–25.8) 0.14<br />

Prevalence hiatal hernia # 345 (85%) 113 (86%) 232 (85%) 0.77<br />

Prevalence defective LES 383 (76%) 130 (79%) 253 (74%) 0.27<br />

Barrett’s esophagus 186 (37%) 50 (30%) 136 (40%) 0.04<br />

Length <strong>of</strong> BE (cm) 3 (2–6) 2 (2–5.5) 4 (2–6) 0.35<br />

Comparative Analysis <strong>of</strong> Risk Factors <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>Esophagus</strong> 563<br />

Figure 1. (A) Results <strong>of</strong> ambulatory 24-h pH and (B) bilirub<strong>in</strong> (Bilitec) monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> pH positive females and males with and without<br />

Barrett’s. <strong>Females</strong> without Barrett’s had significantly less esophageal acid exposure than males without Barrett’s. Further, both females<br />

and males without Barrett’s had significantly less esophageal acid and bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure than their counterparts with Barrett’s. However,<br />

esophageal acid and bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure was similar <strong>in</strong> females and males with Barrett’s.

564 Banki et al.<br />

Table 3. Prevalence <strong>of</strong> an Abnormal Bilitec Test <strong>in</strong> 24-h pH<br />

Positive Patients<br />

No Barrett’s Barrett’s p-Value<br />

<strong>Females</strong> (n = 45) 24 (50%) 21 (95%) 0.0001<br />

Males (n = 96) 51 (55%) 45 (82%) 0.0012<br />

marg<strong>in</strong>ally significant. The youngest female with Barrett’s<br />

was 22yr, while the youngest male was 20 yr old. Physiologic<br />

evaluation demonstrated that the LES characteristics<br />

and esophageal acid and bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure <strong>in</strong> females and<br />

males with Barrett’s were not significantly different, nor was<br />

there a difference <strong>in</strong> the prevalence or size (median 3 cm for<br />

females and 4 cm for males, p = 0.09) <strong>of</strong> a hiatal hernia<br />

(Figs. 1A, B, Table 4).<br />

Predictors <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>Esophagus</strong> <strong>in</strong> Patients<br />

with Reflux Disease<br />

Univariate analysis identified the duration <strong>of</strong> symptoms, presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> hiatal hernia, number <strong>of</strong> reflux episodes, number<br />

<strong>of</strong> reflux episodes last<strong>in</strong>g greater than 5 m<strong>in</strong>, longest reflux<br />

episode, presence <strong>of</strong> a defective LES, and abnormal bilirub<strong>in</strong><br />

exposure as potentially predictive factors for the presence <strong>of</strong><br />

Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> patients with 24-h pH proven reflux. Age and BMI<br />

were not significant factors. Multivariable analysis demonstrated<br />

that <strong>in</strong> both females and males with abnormal 24-h<br />

pH tests, the only significant factor <strong>in</strong>dependently associated<br />

with the presence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s was abnormal bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure.<br />

The odds ratio for the presence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s esophagus<br />

<strong>in</strong> the sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased esophageal bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure was<br />

10.8 for females and 4.8 for males (95% CL 2.3–53, p =<br />

0.006 for females; 1.7–9.8, p < 0.001 for males).<br />

Prevalence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> Patients with Multiple<br />

Physiologic Abnormalities Suggest<strong>in</strong>g Severe<br />

Reflux Disease<br />

With<strong>in</strong> the population <strong>of</strong> 796 patients who underwent evaluation<br />

for reflux symptoms, 98 patients (33 females and<br />

65 males) had physiologic evidence <strong>of</strong> severe gastroesophageal<br />

reflux disease based on the presence <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g abnormalities: a defective LES, a hiatal hernia, and<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased esophageal acid and bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure based on<br />

24-h pH and Bilitec test<strong>in</strong>g. In this subgroup <strong>of</strong> patients the<br />

overall prevalence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s was 54%. Importantly, <strong>in</strong> these<br />

patients with severe reflux disease the prevalence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s<br />

was similar <strong>in</strong> females and males (females: 17/33 (52%) vs<br />

males: 36/65 (55%), p = 0.88).<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

Although a common disorder, much rema<strong>in</strong>s unknown about<br />

the epidemiology <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s esophagus. Most studies have<br />

found dist<strong>in</strong>ct racial and gender differences, with females<br />

and non-Caucasians significantly less likely to have Barrett’s<br />

(14–17). In a study by Rex and colleagues 961 subjects who<br />

presented for screen<strong>in</strong>g colonoscopy <strong>in</strong>itially underwent upper<br />

endoscopy (18). Barrett’s esophagus was found <strong>in</strong> 4.6% <strong>of</strong><br />

females compared to 8.2% <strong>of</strong> males (p = 0.04 by χ 2 ). While<br />

the racial differences <strong>in</strong> Barrett’s are readily expla<strong>in</strong>ed by the<br />

reduced <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> reflux disease among non-Caucasian<br />

populations, the gender difference is less easily understood.<br />

Kennedy et al. noted that the prevalence <strong>of</strong> reflux symptoms<br />

is similar <strong>in</strong> males and females <strong>in</strong> Western populations, and<br />

a study from F<strong>in</strong>land reported that more women than men<br />

were referred for upper endoscopy to evaluate reflux symptoms<br />

(19, 20) (personal communication with Dr. Voutila<strong>in</strong>en).<br />

Further, <strong>in</strong> a recent analysis <strong>of</strong> 4,684 people tak<strong>in</strong>g chronic<br />

acid suppression medication, the majority (55%) were female<br />

(21).<br />

In contrast to the similar prevalence <strong>of</strong> reflux symptoms<br />

and use <strong>of</strong> acid-suppression medication, complications from<br />

reflux disease <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g esophagitis, Barrett’s, and adenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma<br />

<strong>of</strong> the esophagus are known to occur less commonly<br />

<strong>in</strong> females (14, 16, 20, 22, 23). This suggests that either some<br />

factor associated with the female sex protects aga<strong>in</strong>st reflux<br />

complications, or that despite the presence <strong>of</strong> symptoms<br />

Table 4. Physiologic Characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>Females</strong> and Males with Abnormal 24-h pH Tests<br />

LES Pressure Total LES Length Prevalence <strong>of</strong> Prevalence <strong>of</strong> a<br />

(mmHg) (cm) Defective LES (%) Hiatal Hernia (%)<br />

<strong>Females</strong> without BE∗ 6.4 (4.0–10.2) 2.2 (1.8–3.1) 76 82<br />

n = 115<br />

<strong>Females</strong> with BE ‡ 4.1 (1.6–8.4) 1.8 (0.8–3.2) 90 93<br />

n = 50<br />

Males without BE # 6.8 (3.4–12.3) 2.2 (1.4–3.2) 63 84<br />

n = 205<br />

Males with BE † 4.0 (2.0–5.8) 1.8 (1.2–2.6) 91 85<br />

n = 136<br />

Values are medians (<strong>in</strong>terquartile range), or frequency.<br />

∗‡ p-Values significant for all comparisons between females without BE and females with BE except for prevalence <strong>of</strong> a hiatal hernia (LES pressure p = 0.001; LES length p =<br />

0.03; prevalence <strong>of</strong> a defective LES p = 0.04; prevalence <strong>of</strong> a hiatal hernia p = 0.11).<br />

#† p-Values significant for all comparisons between males without BE and males with BE except for prevalence <strong>of</strong> a hiatal hernia (LES pressure p < 0.001; LES length p = 0.006;<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> a defective LES p < 0.0001; prevalence <strong>of</strong> a hiatal hernia p = 0.74).<br />

∗# p-Values not significant for all comparisons between females and males without BE except for the prevalence <strong>of</strong> a defective LES (LES pressure p = 0.79; LES length p = 0.39;<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> a defective LES p = 0.03; prevalence <strong>of</strong> a hiatal hernia p = 0.85).<br />

‡† p-Values not significant for all comparisons between females and males with BE (LES pressure p = 0.41; LES length p = 0.84; prevalence <strong>of</strong> a defective LES p = 0.29;<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> a hiatal hernia p = 0.20).

Comparative Analysis <strong>of</strong> Risk Factors <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>Esophagus</strong> 565<br />

females on average have less severe reflux disease than males.<br />

To answer this question we reviewed the records <strong>of</strong> 796 patients<br />

with reflux symptoms. We were unable to reliably assess<br />

the prevalence <strong>of</strong> esophagitis <strong>in</strong> our patients s<strong>in</strong>ce most were<br />

tak<strong>in</strong>g proton pump <strong>in</strong>hibitors on a regular basis at the time<br />

they presented for evaluation. However, physiologic evaluation<br />

demonstrated that compared to males, females with reflux<br />

symptoms were significantly less likely to have an abnormal<br />

24-h pH test, a defective LES, or a hiatal hernia. S<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

these abnormalities correlate with the severity <strong>of</strong> reflux disease,<br />

we conclude that females, despite the presence <strong>of</strong> reflux<br />

symptoms, have less severe reflux disease on average than<br />

males. Next, we looked specifically at the 506 patients with<br />

reflux disease proven by the presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased esophageal<br />

acid exposure on 24-h pH test<strong>in</strong>g. Overall, females had less<br />

esophageal acid exposure than males, and <strong>in</strong> particular, the<br />

subgroup <strong>of</strong> females without Barrett’s had significantly less<br />

esophageal acid exposure than males without Barrett’s. This<br />

aga<strong>in</strong> suggests that reflux disease on average is less severe <strong>in</strong><br />

females, even when compar<strong>in</strong>g only patients with a positive<br />

24-h pH test.<br />

A strik<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this study was that <strong>in</strong> contrast to the<br />

differences between females and males with reflux but without<br />

Barrett’s, females with Barrett’s were similar to males<br />

with Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> nearly all aspects. Specifically, the manometric<br />

characteristics <strong>of</strong> the LES, the prevalence and size <strong>of</strong><br />

a hiatal hernia, and the degree <strong>of</strong> esophageal acid and bilirub<strong>in</strong><br />

exposure were not significantly different between females<br />

and males with Barrett’s. Thus, by physiologic assessment<br />

females with Barrett’s had a similar severity <strong>of</strong> reflux and<br />

a similar frequency <strong>of</strong> physiologic abnormalities associated<br />

with reflux as males with Barrett’s. Consequently, our data<br />

would suggest that <strong>in</strong> a patient with Barrett’s the physiologic<br />

derangements are similar regardless <strong>of</strong> gender.<br />

To address the question <strong>of</strong> whether female gender rendered<br />

patients with severe reflux disease less likely to develop Barrett’s<br />

we compared the prevalence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> a subgroup<br />

<strong>of</strong> females and males with similar physiologic derangements.<br />

From the <strong>in</strong>itial 796 patients who presented with reflux symptoms<br />

we selected all patients with the follow<strong>in</strong>g comb<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

<strong>of</strong> abnormalities: an abnormal 24-h pH test, an abnormal<br />

Bilitec test, a defective LES, and a hiatal hernia. This group<br />

would be expected to have severe reflux disease, and <strong>in</strong>deed<br />

54% <strong>of</strong> the 98 patients who met these criteria had Barrett’s<br />

esophagus. We found that with<strong>in</strong> this subset <strong>of</strong> patients the<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s was similar <strong>in</strong> females and males (52%<br />

<strong>of</strong> females and 55% <strong>of</strong> males), <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that severe reflux<br />

produced Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> a more than one-half <strong>of</strong> these patients<br />

regardless <strong>of</strong> gender. Importantly, there was no evidence <strong>of</strong> a<br />

protective effect or factor aga<strong>in</strong>st Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> females. However,<br />

why approximately one-half <strong>of</strong> the patients with severe<br />

reflux disease did not have Barrett’s rema<strong>in</strong>s an important<br />

and unanswered question, and future <strong>in</strong>vestigations should<br />

perhaps focus on these patients.<br />

Lastly, we used multivariable analysis to determ<strong>in</strong>e which<br />

factors were <strong>in</strong>dependently associated with the presence <strong>of</strong><br />

Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> patients with 24-h pH proven reflux disease. The<br />

only significant factor associated with the presence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s<br />

<strong>in</strong> patients with reflux disease was abnormal esophageal<br />

exposure to bilirub<strong>in</strong> as determ<strong>in</strong>ed by the Bilitec test. The<br />

likelihood <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g Barrett’s was <strong>in</strong>creased 11-fold <strong>in</strong> females<br />

and 5-fold <strong>in</strong> males with <strong>in</strong>creased bilirub<strong>in</strong> reflux.<br />

This f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g confirms what we previously reported <strong>in</strong> a largely<br />

male group <strong>of</strong> patients with reflux (7). This does not imply<br />

that acid is not important. Indeed, we def<strong>in</strong>ed reflux disease by<br />

the presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased esophageal exposure to acid. Thus<br />

all patients <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the multivariable analysis had abnormal<br />

esophageal acid exposure, but what separated those with<br />

reflux without Barrett’s from those with reflux and Barrett’s<br />

was abnormal esophageal bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure. In fact, 95%<br />

<strong>of</strong> females and 82% <strong>of</strong> males with Barrett’s had an abnormal<br />

Bilitec study, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g a high prevalence <strong>of</strong> duodenogastro-esophageal<br />

reflux <strong>in</strong> patients with Barrett’s. This f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<br />

is <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with the develop<strong>in</strong>g concept that while <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

esophageal acid exposure def<strong>in</strong>es reflux disease and leads to<br />

columnarization <strong>of</strong> the distal esophagus, alkal<strong>in</strong>e or duodenogastric<br />

juice may be more important <strong>in</strong> the development <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>alization (7, 9, 24–26).<br />

The f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> this study have several important cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

implications. First, females with significant reflux are at risk<br />

for Barrett’s, and endoscopy should not be omitted <strong>in</strong> the<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> these patients. Further, although females with<br />

Barrett’s tended to be older than males with Barrett’s, the<br />

youngest female with Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> our study was 22 yr old.<br />

Consequently, age, like gender, cannot be used to reliably exclude<br />

the potential for Barrett’s to be present <strong>in</strong> a patient with<br />

reflux. Lastly, females and males with Barrett’s have been<br />

shown to have a similar risk <strong>of</strong> cancer (23). Therefore, similar<br />

to males, females with reflux are at risk for Barrett’s, and<br />

females with Barrett’s are at risk for esophageal adnenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma.<br />

Although to date this is the largest study that <strong>in</strong>cludes extensive<br />

physiologic evaluation <strong>of</strong> patients with reflux symptoms<br />

(esophageal manometry <strong>in</strong> 98% and 24-h pH monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> 97% <strong>of</strong> patients), we recognize that there are limitations <strong>in</strong><br />

our study. First, only about one-half <strong>of</strong> the patients underwent<br />

Bilitec monitor<strong>in</strong>g. Bilitec test<strong>in</strong>g was not available throughout<br />

the entire timeframe <strong>of</strong> this study, and some patients were<br />

unwill<strong>in</strong>g to undergo the test. While 43% <strong>of</strong> all patients is a<br />

high percentage to have Bilitec test<strong>in</strong>g compared to most retrospective<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical series, ideally all patients would have had<br />

all the tests. This is <strong>of</strong> course unrealistic <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice.<br />

However, we cannot exclude the possibility that a bias existed<br />

<strong>in</strong> the selection <strong>of</strong> patients to undergo Bilitec test<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

We believe though that our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are valid s<strong>in</strong>ce a similar<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> females (49%) and males (46%) had Bilitec<br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g, more patients without Barrett’s had Bilitec monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

than did patients with Barrett’s, and overall less than<br />

one-half <strong>of</strong> the patients studied by Bilitec were found to have<br />

abnormal bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure <strong>in</strong> the esophagus.<br />

Another limit<strong>in</strong>g factor is that patients referred to our center<br />

all had reflux symptoms considered significant enough

566 Banki et al.<br />

to warrant thorough evaluation and potentially antireflux<br />

surgery. The severity <strong>of</strong> reflux is reflected by the 26% overall<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> our patient population. While the<br />

overall severity <strong>of</strong> reflux disease <strong>in</strong> our patients represents<br />

a potential limitation <strong>of</strong> this study, it also provides an excellent<br />

opportunity to determ<strong>in</strong>e the factors associated with<br />

Barrett’s, s<strong>in</strong>ce reflux disease is a prerequisite for Barrett’s<br />

esophagus. The frequency <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>in</strong> our population is<br />

probably higher than would be expected <strong>in</strong> a general medical<br />

practice, but we found that Barrett’s was more prevalent<br />

<strong>in</strong> males, and our male/female ratio <strong>of</strong> 2.7/1 is similar to<br />

what others report (14). This would suggest that although the<br />

severity <strong>of</strong> reflux disease may be skewed <strong>in</strong> our population,<br />

the demographics are probably not. Further, the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g by<br />

Gerson et al. that 25% <strong>of</strong> asymptomatic veterans have Barrett’s<br />

demonstrates that the true prevalence <strong>of</strong> this disease <strong>in</strong><br />

the general population is poorly understood (27).<br />

In conclusion, we found that symptomatic females tend<br />

to have less severe reflux by physiologic test<strong>in</strong>g than symptomatic<br />

males. Even among patients with an abnormal 24-h<br />

pH test but without Barrett’s females on average had less<br />

esophageal acid exposure. However, regardless <strong>of</strong> gender patients<br />

with Barrett’s had severe reflux disease. In both females<br />

and males with reflux, the only significant risk factor for the<br />

presence <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s esophagus was <strong>in</strong>creased bilirub<strong>in</strong> exposure<br />

<strong>in</strong> the esophagus, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g abnormal alkal<strong>in</strong>e reflux.<br />

Importantly, we found no evidence <strong>of</strong> a protective factor <strong>in</strong><br />

females aga<strong>in</strong>st Barrett’s. Rather, given a similar severity <strong>of</strong><br />

reflux disease males and females were equally likely to have<br />

Barrett’s esophagus. Consequently, the reason fewer females<br />

have Barrett’s is that on average females have less severe<br />

reflux than males.<br />

Repr<strong>in</strong>t requests and correspondence: Steven R. DeMeester,<br />

M.D., Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Cardiothoracic <strong>Surgery</strong>, The University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Southern California, 1510 San Pablo St., Suite 514, Los<br />

Angeles, CA 90033.<br />

Received June 12, 2004; accepted September 24, 2004.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. W<strong>in</strong>ters CJ, Spurl<strong>in</strong>g TJ, Chobanian SJ, et al. Barrett’s<br />

esophagus. A prevalent, occult complication<br />

<strong>of</strong> gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology<br />

1987;92(1):118–24.<br />

2. Eisen GM, Sandler RS, Murray S, et al. The relationship between<br />

gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications<br />

with Barrett’s esophagus. (See comments). Am J Gastroenterol<br />

1997;92(1):27–31.<br />

3. Lieberman DA, Oehlke M, Helfand M. Risk factors for<br />

Barrett’s esophagus <strong>in</strong> community-based practice. GORGE<br />

consortium. Gastroenterology Outcomes Research Group <strong>in</strong><br />

Endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92(8):1293–7.<br />

4. Loughney T, Maydonovitch CL, Wong RK. Esophageal<br />

manometry and ambulatory 24-hour pH monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> patients<br />

with short and long segment Barrett’s esophagus. Am<br />

J Gastroenterol 1998;93(6):916–9.<br />

5. Oberg S, DeMeester TR, Peters JH, et al. The extent <strong>of</strong><br />

Barrett’s esophagus depends on the status <strong>of</strong> the lower<br />

esophageal sph<strong>in</strong>cter and the degree <strong>of</strong> esophageal acid<br />

exposure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;117(3):572–<br />

80.<br />

6. Cameron AJ. Barrett’s esophagus: Prevalence and size <strong>of</strong><br />

hiatal hernia. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94(8):2054–9.<br />

7. Campos GM, DeMeester SR, Peters JH, et al. Predictive<br />

factors <strong>of</strong> Barrett esophagus: Multivariate analysis <strong>of</strong> 502<br />

patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Surg<br />

2001;136(11):1267–73.<br />

8. Menges M, Muller M, Zeitz M. Increased acid and bile reflux<br />

<strong>in</strong> Barrett’s esophagus compared to reflux esophagitis, and<br />

effect <strong>of</strong> proton pump <strong>in</strong>hibitor therapy. Am J Gastroenterol<br />

2001;96(2):331–7.<br />

9. Kaur BS, Ouatu-Lascar R, Omary MB, et al. Bile salts <strong>in</strong>duce<br />

or blunt cell proliferation <strong>in</strong> Barrett’s esophagus <strong>in</strong> an<br />

acid-dependent fashion. Am J Physiol Gastro<strong>in</strong>test Liver<br />

Physiol 2000;278(6):G1000–9.<br />

10. Mart<strong>in</strong>ez de Haro L, Ortiz A, Parrilla P, et al. Intest<strong>in</strong>al metaplasia<br />

<strong>in</strong> patients with columnar l<strong>in</strong>ed esophagus is associated<br />

with high levels <strong>of</strong> duodenogastroesophageal reflux.<br />

Ann Surg 2001;233(1):34–8.<br />

11. Cameron AJ, Lomboy CT. Barrett’s esophagus: Age, prevalence,<br />

and extent <strong>of</strong> columnar epithelium. (See comments).<br />

Gastroenterology 1992;103(4):1241–5.<br />

12. Bremner CG, DeMeester T, Bremner R, et al. Esophageal<br />

motility test<strong>in</strong>g made easy. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical<br />

Publish<strong>in</strong>g, 2001.<br />

13. Kauer WK, Burdiles P, Ireland AP, et al. Does duodenal<br />

juice reflux <strong>in</strong>to the esophagus <strong>of</strong> patients with complicated<br />

GERD? Evaluation <strong>of</strong> a fiberoptic sensor for bilirub<strong>in</strong>.<br />

(See comments). Am J Surg 1995;169(1):98–103; discussion<br />

103–4.<br />

14. Hirota WK, Loughney TM, Lazas DJ, et al. Specialized<br />

<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer <strong>of</strong> the esophagus<br />

and esophagogastric junction: Prevalence and cl<strong>in</strong>ical data.<br />

Gastroenterology 1999;116(2):277–85.<br />

15. Gerson LB, Edson R, Lavori PW, et al. Use <strong>of</strong> a simple symptom<br />

questionnaire to predict Barrett’s esophagus <strong>in</strong> patients<br />

with symptoms <strong>of</strong> gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol<br />

2001;96(7):2005–12.<br />

16. Conio M, Cameron AJ, Romero Y, et al. Secular trends <strong>in</strong><br />

the epidemiology and outcome <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s oesophagus <strong>in</strong><br />

Olmsted County, M<strong>in</strong>nesota. Gut 2001;48(3):304–9.<br />

17. Conio M, Filiberti R, Blanchi S, et al. Risk factors for<br />

Barrett’s esophagus: A case-control study. Int J Cancer<br />

2002;97(2):225–9.<br />

18. Rex D, Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs O, Shaw M, et al. Screen<strong>in</strong>g for Barrett’s<br />

esophagus <strong>in</strong> colonscopy patients with and without heartburn.<br />

Gastroenterology 2003;125:1670–7.<br />

19. Kennedy TM, Jones RH, Hung<strong>in</strong> AP, et al. Irritable<br />

bowel syndrome, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and bronchial<br />

hyper-responsiveness <strong>in</strong> the general population. Gut<br />

1998;43(6):770–4.<br />

20. Mantynen T, Farkkila M, Kunnamo I, et al. The impact <strong>of</strong><br />

upper GI endoscopy referral volume on the diagnosis <strong>of</strong><br />

gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications: A 1-<br />

year cross-sectional study <strong>in</strong> a referral area with 260,000<br />

<strong>in</strong>habitants. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97(10):2524–9.<br />

21. Jacobson BC, Ferris TG, Shea TL, et al. Who is us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

chronic acid suppression therapy and why? Am J Gastroenterol<br />

2003;98(1):51–8.<br />

22. Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, et al. Risk factors<br />

for erosive reflux esophagitis: A case-control study. Am J<br />

Gastroenterol 2001;96(1):41–6.<br />

23. Solaymani-Dodaran M, Logan R, West J, et al. Risk <strong>of</strong><br />

oesophageal cancer <strong>in</strong> Barrett’s oesophagus and gastrooesophageal<br />

reflux. Gut 2004;53:1070–4.

Comparative Analysis <strong>of</strong> Risk Factors <strong>of</strong> Barrett’s <strong>Esophagus</strong> 567<br />

24. Csendes A, Maluenda F, Braghetto I, et al. Location <strong>of</strong><br />

the lower oesophageal sph<strong>in</strong>cter and the squamous columnar<br />

mucosal junction <strong>in</strong> 109 healthy controls and 778 patients<br />

with different degrees <strong>of</strong> endoscopic oesophagitis. Gut<br />

1993;34(1):21–7.<br />

25. Kauer WK, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, et al. Mixed reflux <strong>of</strong><br />

gastric and duodenal juices is more harmful to the esophagus<br />

than gastric juice alone. The need for surgical therapy reemphasized.<br />

(See comments). Ann Surg 1995;222(4):525–<br />

31; discussion 531–3.<br />

26. Fitzgerald RC, Omary MB, Triadafilopoulos G. Dynamic effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> acid on Barrett’s esophagus. An ex vivo proliferation<br />

and differentiation model. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Invest 1996;98(9):2120–8.<br />

27. Gerson LB, Shetler K, Triadafilopoulos G. Prevalence <strong>of</strong><br />

Barrett’s esophagus <strong>in</strong> asymptomatic <strong>in</strong>dividuals. (comment).<br />

Gastroenterology 2002;123(2):461–7.