Issue 3 - SEXTONdigital

Issue 3 - SEXTONdigital

Issue 3 - SEXTONdigital

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

______ . ;,.,.___. ~..-..~'--'<br />

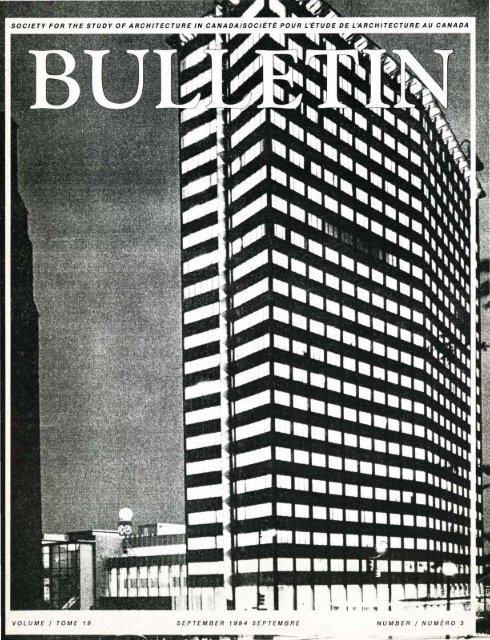

VOLUME I TOME 19 SEPTEMBER 1994 SEPTEMBRE NUMBER I NUMERO 3

Society for the Study of<br />

Architecture in Canada<br />

Societe pour !'etude de<br />

!'architecture au Canada<br />

President I presidente<br />

Diana Thomas<br />

State Historic Preservation Office<br />

Arizona State Parks Department<br />

800 W. Washington, Suite 41S<br />

Phoenix, Arizona 8S007<br />

Past President 1 ancien president<br />

Mark Fram<br />

1S9 Russell Hill Road, No. 101<br />

Toronto, Ontario M4V 2S9<br />

Vice-President I vice-presidente<br />

Dorothy Field<br />

Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism<br />

Old St. Stephen's College, 8820 112 Street<br />

Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2P8<br />

Treasurer I tresorier<br />

EdgarTumak<br />

309 Stewart Street, Apt S<br />

Ottawa, Ontario KIN 61

J n This <strong>Issue</strong> I L e numero de ce mois-ci<br />

The two articles featured in this issue of the<br />

.1. Bulletin demonstrate that the 20th century<br />

covers a lot of architectural territory. In the first<br />

article, architecture looks to the future, unimpeded<br />

by the past; in the second article, architecture draws<br />

from the past to give meaning to the present.<br />

University of British Columbia professor<br />

Rhodri Windsor Liscombe charts new territory with<br />

his explanation of how Modernism came to Canada<br />

in the mid 20th century. In "Modes of Modernizing:<br />

The Acquisition of Modernism in Canada,"<br />

Liscombe focuses on the West Coast, explaining<br />

how Modernism found more ready acceptance there<br />

than in other regions of the country. Based on exhaustive<br />

research and interviews with many of the<br />

premier architects of the era, he submits that their<br />

Modernist convictions were acquired primarily from<br />

three sources: from their formal university training<br />

and in various progressive offices; from theoretical<br />

books; and from professional journals and<br />

magazines. Liscombe explains convincingly how<br />

Modernism came to be embraced by local architects<br />

and adapted to the West Coast milieu.<br />

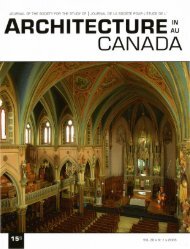

In "The First Synagogues in Ottawa,"<br />

Hagit Hadaya describes the circumstances which<br />

produced the first generation of synagogues in the<br />

nation's capital. She first outlines the situation of the<br />

immigrants, and their requirements for creating<br />

suitable places of worship. Each of the first four<br />

synagogues is then interpreted as both an architectural<br />

and sociological expression of their faith.<br />

The congregations' attempts to import some of the<br />

reassuring conventions of their Eastern European<br />

homes to Ottawa- in spite of employing non<br />

Jewish architects- is clearly demonstrated in the<br />

structures they erected.<br />

Two letters round out this Bulletin, both<br />

on the subject of architectural periodicals proffered<br />

in the last issue.<br />

L<br />

es deux articles publics dans ce numero du<br />

Bulletin montrent que le xx• siecle couvre un<br />

large territoire architectural. Dans le premier,<br />

!'architecture se tourne resolument vers le futur, sans<br />

egard au passe; dans le second, au contraire, elle<br />

s'appuie sur ce passe pour donner une signification au<br />

present.<br />

Professeur a !'University of British Columbia,<br />

Rhodri Windsor Liscombe propose de nouvelles voies<br />

d'explication sur !'introduction du modernisme au<br />

Canada au milieu du xx• siecle. Dans "Modes of<br />

Modernizing: The Acquisition of Modernism in<br />

C'.anada", il se penche sur Ia region de Ia c6te ouest, et<br />

demontre comment le modernisme y a ete plus facilemen!<br />

re~u qu'en d'autres lieux au pays. Fondant son<br />

argumentation sur ses recherches exhaustives et sur les<br />

entrevues qu'il a menees avec plusieurs architectes de<br />

cette periocle, il suggere que leurs convictions modernistes<br />

ant ete acquises a partir de trois sources principales: lors<br />

de leur formation universitaire et de leur pratique dans<br />

diverses firmes progressistes; dans des ouvrages<br />

theoriques; dans des revues professionnelles et des<br />

magazines. Convainquant, il explique comment le<br />

modernisme a finalement ete adopte par les architectes<br />

locaux et ada pte aux particularites de Ia c6te ouest.<br />

Dans "The First Synagogues in Ottawa", Hagit<br />

Hadaya decrit les circonstances qui ont mene a<br />

l'etablissement des premieres synagogues dans Ia region<br />

de Ia capitate nationale. Elle s'attarde d'abord a Ia situation<br />

des immigrants et a leurs besoins d'avoir des lieux<br />

de culte appropries. Elle interprete ensuite chacune des<br />

quatre premieres synagogues qui ont ete construites en<br />

tant qu'expression architecturale et sociologique de leur<br />

foi. 11 apparaft evident a Ia lumiere de son analyse que<br />

"in spite of employing non-Jewish architects", les<br />

structures erigees montrent nettement des traits de<br />

!'architecture de !'Europe de l'est, procurant ainsi aux<br />

immigrants un reconfort certain par leur evocation de<br />

leurs lieux d'origine.<br />

Ce Bulletin se termine par Ia publication de<br />

deux lett res port ant sur Ia question des periodiques en<br />

architecture, question deja abordee dans le numero<br />

precedent.<br />

19:3<br />

SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 59

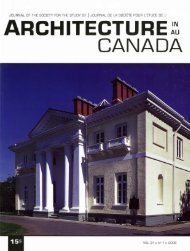

Modes of Modernizing:<br />

Modernist Design<br />

BY RHODRI WINDSOR<br />

60 SSAC BULLETIN 19:3

The Acquisition of<br />

in Canada<br />

LISCOMBE<br />

The means by which Canadian- and indeed international-architects<br />

acquired an understanding of<br />

Modernist design is more assumed than researched .,<br />

The issue is highly complex since it embraces a range<br />

of factors from the educational policy or educative<br />

competence of faculty in the schools of architecture, to<br />

the intellectual, technical, and creative competence of<br />

the individual students, to the disparate nature of<br />

Modernist theory and practice. However, the main lines<br />

of that process can be summarized by reference to the<br />

self-directed learning and institutional training undertaken<br />

by those Canadian architects who began<br />

practice on the West Coast during the decade following<br />

the Second World War.<br />

The choice of British Columbia, and especially<br />

Vancouver, as the geographical focus - and to a lesser<br />

extent of residential design as the typological focus- is<br />

determined by the speedier acceptance of Modernist<br />

values there than elsewhere in Canada. 2 This resulted<br />

from the economy and population's considerable<br />

expansion after 1946, and from the fact that for many,<br />

architects included, British Columbia afforded a more<br />

habitable climate and more liberal cultural environment<br />

in which to experiment with progressive design<br />

principles demonstrably relevant to a "baby-boom"<br />

society. 3 The recounted experiences of members of<br />

that generation of architects, a brief analysis of their<br />

work, and an investigation of related documentary<br />

material form the basis of this interim study. 4<br />

Figure 19. Nathan Nemetz residence, Vancouver,<br />

designed in 1948 by John Porter and Catherine Chard<br />

Wisnicki. (Post and Beam [Vancouver: B.C. Lumber<br />

Assn., 1960], cover)<br />

fo r John Bland<br />

19:3<br />

SSAC BULLETIN<br />

61

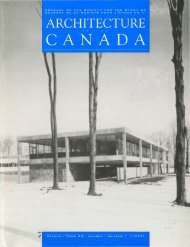

Figure 1 (above). The B.C. Research Council Building,<br />

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, designed by<br />

C.J. Thompson with C. E. Pratt and R.AD. Berwick,<br />

1947. (R. Windsor Liscombe, 1994)<br />

Figure 2 (below). The Hebb Physics Mdition,<br />

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, designed by<br />

Richard Archambault under the supervision of Roy<br />

Jessiman, 1956. (R. Windsor Liscombe, 1994)<br />

T:hese sources yield interesting results that challenge aspects of the conventional interpretation<br />

of Western Canadian and Modernist architectural history. Firstly, West Coast<br />

Modernism developed less from regional imperatives than from the local application of essentially<br />

international ideas and imagery during what might be termed the "stoical phase" of<br />

Modernism in British Columbia, between demobilization and the Vancouver recession of<br />

1960-61. That is not to undervalue either the primary influence of site and climate or the<br />

notable talents of native architects, exemplified by naming but five from the period: Bill<br />

Birmingham, C.E. " Ned" Pratt, Fred Hollingsworth, Arthur Erickson, and Barry Downs.<br />

Rather, it is to state that most architects of that generation appreciated the Modernist<br />

interest in accommodating regional and local cultural factors, and believed that the tenets of<br />

international Modernism offered a valid means to express personal and even national<br />

aspirations, as was the case in contemporary Canadian abstract art. 5<br />

Secondly, the comprehension of Modernism by architectural faculty and students<br />

depended as much upon visual as theoretical material. In the same manner, Modernist<br />

theory was less a homogeneously defined set of principles than a diverse body of part-ethical<br />

and part-aesthetic objectives given renewed relevance by post-war Reconstruction. 6 Thirdly,<br />

illustrations of European and American Modernist design in professional and other journals<br />

62<br />

SSAC BULLETIN 19:3

were cited by designers as having influenced them. This not only underscores the continuing<br />

significance of the published image in the currency of architectural practice, but anticipates<br />

the necessary concerns of B.C. architects with geographical setting and the use of local<br />

materials, especially wood. Fourthly, while the contribution of locally-born and -trained architects<br />

was very substantial, the development of West Coast Modernism depended significantly<br />

upon the immigration of architects and ideas inspired by the transatlantic<br />

Modernist movement; British Columbia artist B.C. Binning, for example, became a leading<br />

proponent of Modernism and built his pioneering West Coast Modern house (1940) after<br />

studying with Ozenfant and being enthused by Modernist British and European design_?<br />

Two buildings erected on the fast-growing campus of the University of British<br />

Columbia manifest the broad acceptance of the abstract functionalist values at the core of<br />

early 20th-century Modernism: the B.C. Research Council Building, begun in 1947 to the<br />

designs of C.J. Thompson (until the early 1940s a staunchly Arts-and-Crafts-cum-Gothicist),<br />

assisted by C.E. Pratt and R.A.D. Berwick (figure I); and the Hebb Physics Addition of 1956<br />

by Richard Archambault, working under the supervision of Roy Jessiman as Thompson, Berwick<br />

and Pratt's partner in charge of the university's architecture (figure 2). The exposed reinforced<br />

concrete structure and equally austerely functional brick and steel frame window infill<br />

of the B.C. Research Council Building correspond with the stoical efficiency of between-thewars<br />

Dutch Modernism, epitomized by Brinkman and van der Vlugt's widely-illustrated van<br />

Nelle coffee, tea, and tobacco factory at Rotterdam (1928-30) (figure 3). Similarly, the Hebb<br />

Physics Addition clearly reveals that Archambault and Jessiman had studied such canonic<br />

works as Gropius and Meyer's Fagus shoe-last factory at Alfeld (1911) and had comprehended<br />

the new concepts of design it embodied (figure 4). It is the inspiration, not the imposition,<br />

of Modernist imagery and associated ideology that is readily apparent in these<br />

Canadian university buildings.<br />

The adaptive nature of such West Coast architecture reflects the relatively small<br />

number of Canadian Modernists who, until the mid-1950s, had actually travelled to the<br />

European or North American sources. Among those who had was Archambault. Funded by<br />

the progressively inclined British Pilkington Glass Company, he went to study in Britain and<br />

on the continent in 1956. There had been a few others before the war, notably during the<br />

1930s: University of Toronto School of Architecture graduates Fred Lasserre (graduated<br />

·1934) and J.B. Parkin (graduated 1935), who worked in Britain; Peter Thornton, a native of<br />

Western Canada, who was trained at the Architectural Association in London from 1934 to<br />

1938. Later exceptions included Jessiman and John Porter, on war service, and Arthur Erickson,<br />

intent upon visiting the renowned architecture of the 1951 Festival of Britain in London<br />

but redirected to unlearning some of the Modernist dogma on a two-year tour of the Mediterranean<br />

basin. 8<br />

A majority of architects had not ventured abroad; indeed, they had attended architectural<br />

schools with fundamentally Beaux-Arts typed programmes. Harold Semmens and<br />

Douglas Simpson, the acknowledged leaders of advanced Modernism in Vancouver through<br />

the early 1950s, had graduated just before the outbreak of war from the University of<br />

Manitoba, when it was under the direction of the conservatively-inclined Milton Osborne and<br />

John Russell (himself a graduate of the Beaux-Arts era at M .I.T. in Cambridge, Massachusetts).<br />

The annual curricula printed in the university calendars through the 1930s disclose<br />

no real alteration to accommodate Modernist thought or process. 9 Yet, without benefit<br />

of specific Modernist education or exposure, Semmens and Simpson were to be responsible<br />

for such early icons of Vancouver Modernism as the adeptly synthesized Miesian/Corbusian<br />

Marwell Office Building (1950-51), recipient of a 1952 Massey Gold Medal and signal of the<br />

acknowledged pre-eminence of B .C. Modernism in the post-war decade (figure 5). tO<br />

Figure 3 (left). The van Nelle coffee, tea, and tobacco<br />

factory at Rotterdam, designed by Brinkman and van<br />

der Vlugt, 1928-30. (The International Style:<br />

Architecture since 1922 [New York: Museum of<br />

Modern Art, 1932]).<br />

Figure 4 (right). The Fagus shoe-last factory at Alfeld,<br />

designed byGropius and Meyer, 1911. (Art in<br />

America, January/February 1979).<br />

19:3 SSAC BULLETIN<br />

63

Figure 5 (above). Interior view ol the Marwe/1 Office<br />

Building, Vancouver; Semmens and Simpson,<br />

architects, 1950-51. (Journal of the Royal<br />

Architectural Institute of Canada (JRAIC)35, no. 4<br />

[April1958]: 136)<br />

Figure 6 (below). The Buchanan Building, University of<br />

British Columbia, Vancouver, 1955-57; loltan Kiss,<br />

project architect, under the supervision of Roy<br />

Jessiman ol Thompson, Berwick and Pratt. (U.B.C.<br />

Special Collections)<br />

Clearly, Semmens and Simpson had attained beyond the confines of academe a<br />

thorough understanding of Modernist principles fully as accomplished as that of the Hungarian-born<br />

and -trained Zoltan Kiss, who was project architect at Thompson, Berwick and<br />

Pratt under Jessiman for the more derivative Miesian Buchanan Building at U _B.C. (1955-<br />

57) (figure 6)- It was designed nearly six years after Kiss had emigrated from Hungary (and<br />

three years after joining Sharp & Thompson, Berwick, Pratt, that nursery of Vancouver<br />

Modernism), where he trained at the Bauhaus-influenced Technical University of Budapest<br />

(following Peter Kaffka, who also emigrated to Vancouver), and, thereby, was more directly<br />

aware of the extensive Modernist design in central Europe_<br />

However, the correspondence between post-war Vancouver and prewar E uropean<br />

Modernist design is, as indicated by the foregoing, more general than specific, and adaptive<br />

rather than imitative_ In this respect, the young Canadian designers comprehended an essential<br />

principle of the Modernist polemic, for the leading proponents eschewed stylistic<br />

categorization and formulaic doctrine_ "Form is not the aim of our work, but only the result,"<br />

64<br />

SSAC BULLETIN 19:3

Figure 7. St. Cuthbert's Anglican Church, Town of<br />

Mount Royal, Montreal, built 1946-47; Frederic<br />

Lasserre, architect, with Wolfgang Gerson and Rolf<br />

Duschenes, associate architects. (JRAIC 28, no. 1<br />

[January 1951]: 9)<br />

Mies van der Rohe had declared in 1923, while Gropius wrote twelve years later that the<br />

Bauhaus represented " not the invention of a new system of architectural education ... but<br />

rather the relation of architecture to the evolving world which is implied by that system." 11<br />

Clear in their own comprehension of objective and means, Gropius and Mies underestimated<br />

the imitative predilection of architectural practice and the tendency of formal education to<br />

codify and to detach example from principle.<br />

Nevertheless, the comparison between the Marwell office and Buchanan Building<br />

does serve to introduce two factors germane to the theme of how Modernism was learned in<br />

canada. The first is the substantive impact of those trained outside the province, necessarily<br />

in the absence of an architectural school on the West Coast, and of those who emigrated<br />

from overseas or migrated from eastern North America. Of the former, Berwick, Birmingham,<br />

and Pratt, although each B. C.-born, graduated from the University of Toronto, respectively<br />

in 1935, 1938, and 1939. Here they had been initiated into some Modernist lore by Eric<br />

Arthur, who, after 1935, led the reform-or modernization-of architectural education in<br />

canada, despite never being appointed head. C.B.K. Van Norman moved to B.C. in 1935<br />

upon graduating from the University of Manitoba ahead of Semmens, Simpson, and, in 1954,<br />

Jessiman. No less remarkable were the alumni of McGill (where Lasserre taught briefly in<br />

1945-46): catherine Chard (Wisnicki), 1943; Duncan McNab, 1941; John Porter, 1941; M.C.<br />

Utley and Arthur Erickson, 1951; and H. Peter Oberlander, 1945.<br />

Oberlander also studied at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, as did Geoffrey<br />

Massey and Abraham Rogatnick, two more easterners who, like the artist Lawren Harris,<br />

were in the words of Erickson "seekers of a new life.'' 12 Oberlander, furthermore, had<br />

been among those who quitted National Socialist Germany yet were interned in canada,<br />

together with Wolfgang Gerson and Rolf Duschenes; in 1944, they teamed up with Lasserre<br />

to design the pioneering Modernist St. Cuthbert's Anglican Church, erected in the Town of<br />

Mount Royal, Montreal (figure 7). In company with Oberlander, Gerson would embark<br />

upon a distinguished teaching career at the universities of Manitoba, from 1946 to 1956, and<br />

British Columbia, there becoming a colleague of both Oberlander and Lasserre. 13<br />

Also from European and/or British training-Gerson attended the Architectural<br />

Association in London between 1936 and 1939---came Francis Donaldson, Kenneth<br />

Gardner, Michael Garrett, Asbjord Gathe, Gerald Hamilton, Warnett Kennedy, Christopher<br />

Owtram, John Peeps, Wilfrid Ussner, and Harold Weinrich. An equally incomplete list of<br />

engineer-designers would include John Read, Paul Wisnicki, and, most importantly, given<br />

their respective contributions to such major commissions as the B.C. Electric head office<br />

(1955-57) and main branch of the Vancouver Public Library (1956-57), Otto Safir and Per<br />

Kristoffersen (ligures 8, 9, and cover). Several, like Garrett, were drawn by the reputation of<br />

19:3 SSAC BULLETIN<br />

65

Figure 8 (right). The main branch of the Vancouver<br />

Public Library, 1956-57; Semmens and Simpson,<br />

architects; Per Ktistoffersen, engineer. (JRAIC 35, no.<br />

4 [April1958}: 141)<br />

Figure 9 (below right). B.C. Electric Building, 1955-57;<br />

Thompson, Berwick and Pratt, architects; Otto Safir,<br />

engineer. (JRAIC 35, no. 4 [April 1958}: 121}<br />

66 SSAC BULLETIN 19:3

B.C. architecture or, like Wells Coates, University of B.C. engineering graduate and founding<br />

Modernist, by specific projects such as Alcan's new town at Kitimat in northern B.C., originally<br />

thought (by Massey for one) to promise comparison with the German Siedlung, Le<br />

Corbusier's Ville Radieuse (1933/35), and contemporary British New Towns. 14<br />

The second factor germane to how Modernism was learned in Canada is the importance<br />

of the McGill connection, both professionally and historically. It was not merely the<br />

long-term consequence of Lasserre's acceptance of the post of head of the School of Architecture,<br />

founded at the University of B.C. in 1946-47. 15 Nor was it simply the fact that Erickson<br />

and other McGill graduates would put their training under John Bland to signal effect. 16<br />

It was also because Chard, McNab, and Porter had participated in the 1938 student mutiny at<br />

McGill didactic, institutional training or, less frequently, articling with a firm (the genesis,<br />

in the office of Sharp & Thompson, Berwick, Pratt, of both Hollingsworth and<br />

Ron Thorn);<br />

> literary, chiefly the theoretical or historio-critical books;<br />

> and professiona~ the journals and magazines covering current practice.<br />

In 1937-38, as already stated, the didactic remained academic, essentially Beaux-Arts, with<br />

the partial exception of the University of Toronto. Even Peter Thornton at the A.A. had<br />

been required to memorize celebrated historical edifices in plan, section, and detail. Although<br />

befriended by Marcel Breuer briefly in England before joining Gropius at Harvard in 1937,<br />

Thornton updated traditional English framing in his thesis project design to formulate the<br />

quasi-Modernist post-and-beam system he would utilize in the house he designed for his<br />

mother at Caulfield, West Vancouver, upon returning to B.C. in 1938. 20<br />

After the academic year 1940-41, Bland, aided by the place of the McGill school in<br />

the Faculty of Engineering and encouraged by the university president, Dr. Cyril James,<br />

moved somewhat more speedily than Eric Arthur toward a Bauhaus-informed five-year architectural<br />

curriculum, to be adapted by Lasserre and later by John Russell. Bland retrospectively<br />

summarized the contents and objectives of the curriculum in an article printed in<br />

the July 1960 issue of the Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (to which I<br />

have added comments):<br />

We give them fundamental mathematics and physics for analytical work and for training their minds. We give them<br />

rather a lot of history of architecture to show them the solid remains of the civilizations that have produced our<br />

thought and feeling [note the emphasis on broad cultural rather than archaeological study}. We teach them to draw<br />

[Arthur Lismer and Gordon Webber (a pupil of Moholy-Nagy at the Chicago Bauhaus) both taught a compressed version<br />

of the "Vorkurs" through the 1950s} and we teach practice in building construction because above all we believe ar·<br />

chitecture is fundamentally good building {the early post·war faculty included such admirers of Le Corbusier as Watson<br />

Balharrie and Hazen Size} .... We teach that design evolves from construction, exploring how space can be built for<br />

human use and finally how space can not only be built well to meet social needs usefully [sociology was inserted into<br />

the programme from 1943} but also meaningfully which is perhaps the real creed of architectureU<br />

Therein Bland neatly defined the Modernist ethos as understood by the post-war generation<br />

of B.C. architects, according to their published or spoken views.<br />

19:3 SSAC BULLETIN 67

Figure 10 (above). Side view of Wembley Swimming<br />

Pool, designed by Owen Williams, 1936. (Architectural<br />

Review, 1938)<br />

Figure 11 (right). The house designed by Serge<br />

Chermayeff near Rugby, England, completed in 1936.<br />

(JRAIC 13, no. 4 [Apri/1936}: 73)<br />

Yet, this is to beg a host of questions which are, and were, implicit in the other<br />

primary means of learning about Modernism available to that generation: the published<br />

theoretical and polemical literature. The diversity contained deeper within a superficially<br />

homogeneous Modernist theory is reflected in the divergent architectural interpretation of<br />

Modernism, even in the relatively small temporal and geographical confines of the post-war<br />

decade in B.C. One explanation, which tended to perpetuate allegiance to the balder<br />

aphorisms and motifs, is the noticeable imprecision about effects, not less than methods, in<br />

the language of Modernist theory. An obvious example is the profession's advocacy of internationalism<br />

and the architect's pre-eminent place in fabricating a new societi simultaneously<br />

with the endorsement of democratic humanism and regional consciousness. 2<br />

Those philosophically unresolved polarities were just as evident in 1937-38, if excused<br />

as being the inevitable concomitant of the reforming dynamic. With Eric Arthur (by<br />

now established as editor of the R.A.I.C. Journal and professor of architectural design at the<br />

University of Toronto), Modernist ideology and design received increasing exposure, though<br />

not entirely clear explication. Thus, in the June 1938 Journal, Arthur reQrinted l..asserre's article<br />

entitled "Modern Architecture: The New Aesthetics and Cement." 23 In it, I..asserre drew<br />

chiefly upon his experience in the office of Berthold Lubetkin's Tecton firm, and as layout<br />

designer for the M.A.R.S. (Modern Architecture Research Group) 24 exhibition in London<br />

that year. While l..asserre argued that Modernism comprised a set of principles and a process<br />

of design rather than a style-being concentrated upon the satisfaction of practical,<br />

economic, and cultural function through the integration of industry and technology-he also<br />

declared, with particular reference to a side view of Owen Williams' 1936 Wembley Swimming<br />

Pool, that it embraced the "Drama and excitemen~roduced by the introduction of new<br />

forms and the association of new materials" (figure 10).<br />

A comparable superficial cohesion masking an underlying ideological division exists<br />

between the most widely used Modernist texts, the 1927 English translation of Le Cor busier's<br />

1923 Vers une architecture, Bruno Taut's Modern Architecture of 1927, Walter Gropius's The<br />

new Architecture and the Bauhaus of 1935, and Siegfried Giedion's Space, Time and Architecture<br />

of 1941. It also exists within their texts, particularly in Le Corbusier's Towards a New Architecture.<br />

Corbusier's argument-albeit relevant to this country by virtue of its often<br />

overlooked Canadian content: an ubiquitous grain elevator from Fort William and a view<br />

along the deck of the Canadian Pacific Empress of France-is riddled with veritable Blakean<br />

aphorisms and discourses as much upon mythic, even mystical, as mechanistic or materialist<br />

values. Hence, the association of his deeply humanistic and complex concept of design with<br />

such deliberately contracted phrases as "A house is a machine for living in," and the general<br />

over-simplification of the Modernist argument for the humanization of technology by its aesthetic<br />

integration into contemporary conditions of living.<br />

Seasoned supporters (in the intellectual or practical sense) of Modernism contributed<br />

to the confusion of its aims, perhaps the most celebrated being Henry-Russell<br />

Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, who mounted the 1932 exhibition The International Style:<br />

68<br />

SSAC BULLETIN 19:3

Figure 12. Ernst Plischke's villa on the shores of Lake<br />

Alter, Austria, 1936. (l'Architecture d'auiourd 'hui,<br />

mars 1937)<br />

Architecture since 1922 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.Z 6 They cast the movement<br />

in terms of a style, seeking to circumvent opposition to the exhibition from the professional<br />

and dilettante establishments. Consequently, they ignored the considerable differences<br />

of conception, intention, and execution between buildings selected for exhibition or illustration,<br />

implying that, say, Ludvik and Kysela's Bata Shoe Store, Prague, 1929, or Mies's<br />

Tugendhat house, Brno, 1931, embodied their tripartite definition of Modernism: "volume<br />

rather than mass ... re~ularity rather than axial symmetry ... (and the proscription of] arbitrarily<br />

applied decoration." 7<br />

Mies might quip in later years, "I read a few good books- and that's about it," but<br />

the diffuse nature of the book literature explains why Catherine Chard Wisnicki and no<br />

doubt most of her peers instead learned much if not most about Modernism from the<br />

magazines. 28 To her, the best was L 'Architecture d'aujourd'hui, though, as a student, she also<br />

regularly perused theAmericanArchitect and Architecture and its successor, theArchitectural<br />

Record, the British Architectural Review, and, once resident in B.C., the much admired<br />

Californian Arts and Architecture.<br />

Through 1937-38 those magazines and the R.A.l.C. Journal-from 1938, "current<br />

magazines" were required reading in Eric Arthur's Elements of Architectural Form coursedid<br />

present a comprehensive picture, or series of images, of Modernist design. According to<br />

Chard Wisnicki, the magazines facilitated her understanding of a number of Modernist<br />

objectives. One she described as the intellectual challenge thrown down by Le Corbusier to<br />

fabricate a relevant form for the epoch, and his sense of the profound meaning that could be<br />

imported through the disposition of space. Another was the goal of an integrated welding of<br />

material, structure, and purpose desired by Gropius and Mies. A third was the formal and<br />

structural logic and the variety of space and scale achieved by the Dutch Modernists. And a<br />

fourth aim was the transformation of functional and technological factors into humanistic<br />

and naturalized buildings attained by Alvar Aalto. The photographs in the magazines were<br />

not infrequently both striking and evocative of the attitudes and aspirations that had determined<br />

their appearance.<br />

Each of these issues seems to be present in the photograph of the presciently militaristic<br />

geometrical-functional house (much admired by Jessiman when a student) which Serge Chermayeff<br />

had completed outside Rugby in 1936, published by Eric Arthur in a 1938 R.A.I.C. Journal<br />

(figure 11 ); the use of presciently avers to the material and ideological ground-clearing for<br />

Modernism begun by the First and finished by the Second World War. Interestingly, Chermayeffs<br />

all-timber house at Halland, Sussex (1937-38}-essentially post-and-beam or proto-West Coast<br />

Modernist-was illustrated in J. McAndrew and E. Mock's popular Museum of Modern Art<br />

booklet What i5 Modem Architecture? (1946), as well as in J.M. Richard's An Introduction to<br />

ModemArchitec11.u-e ( 1940), which became required summer reading at McGill from 1942. An<br />

even more powerful image of the stoical formalism and technological functionalism of mid-<br />

1930s Modernism was Chermayeffs I.C.l. Laboratory at Blackley, Manchester, England, extensively<br />

reported in the March 1938 issue of Architectural Review.<br />

19:3 SSAC BULLETIN<br />

69

:-=-~-~~

Figure 18 (above). House at Richmond Shore,<br />

California; William Wurster, architect, 1937.<br />

(Architectural Record 83, no. 1 [January 1938))<br />

Figure 20 (top left). The Oberlander residence,<br />

Vancouver, 1958; H. Peter Oberlander and Leon G.<br />

Oirassar, architects. (Western Homes and Living,<br />

August 1960, 21)<br />

Figure 21 (middle left). The McNab residence, West<br />

Vancouver, 1957; Duncan McNab, architect. (JRAIC<br />

35, no. 4 [April1958): 126)<br />

Figure 22 (bottom left). The Wolfgang Gerson<br />

residence, West Vancouver, 1958; Wolfgang Gerson,<br />

architect. (Western Homes and Living, August 1960,<br />

21)<br />

19:3 SSAC BULLETIN<br />

71

Gropius and Fry's timber house at Shipbourne, England, reported in the February 1938<br />

Architectural Review (figure 17). The procedures and product for a Modernist idiom attuned<br />

to the Pacific Northwest were vividly explicated by the photographs of contemporary California<br />

houses placed in L 'Architecture d'aujourd'hui and Architectural Record. The stunning<br />

triptych of houses published on one page of the January 1938 Record epitomized the celebration<br />

of the symbiotic unification of Modernist practice and natural setting achieved by<br />

Richard Neutra, Rudolf Schindler, and William Wurster (figure 18)? 1<br />

The prestige of West Coast United States architects, especially Neutra, Wurster,<br />

Pietro Belluschi, John Funk, and Raphael Soriano (regularly illustrated in Arts and Architecture),<br />

would compound through the 1950s. 32 Nevertheless, for Western Canadian Modernists<br />

the legacy of the transatlantic inspiration upon the formative process of Modernization<br />

just prior to the Second World War was significant. It is apparent in the Nathan Nemetz<br />

house, designed in 1948 by Porter and Chard Wisnicki (replacing the too-demanding Frank<br />

Lloyd Wright). 33 The shed roof spanning the living room and master bedroom, placed in<br />

front of the cross-axial rear service and bedroom wing in order to capitalize on the location,<br />

realigns the site slope to launch the gaze through the Mies-cum-Neutra glass walls across<br />

English Bay to the sublime North Shore mountains (figure 19; see pages 60-1).<br />

THE USE OF NATURAL YET ECONOMICAL MATERIALS and the embrace of setting at the<br />

Nemetz house, plus the efficient and habitable plan, demonstrate the essential breadth of<br />

Modernist intent. They even foreshadow Ron Thorn's comment "The landscape must win in<br />

the end." 34 And the legacy of transatlantic Modernism persisted in the conceptually consistent<br />

houses on diverse sites designed for themselves by Oberlander (1958) in Vancouver, and<br />

by McNab (1957) and Gerson (1958) in West Vancouver (figures 20, 21, 22). These houses<br />

variously exhibit the architectural and ideological stimuli of international Modernism to which<br />

a graduate of the University of Toronto School of Architecture humorously alluded in his<br />

brief fictitious valedictory for Torontonensis of 1939:<br />

... came to varsity from London, resigning from Tecton Partnership with Lubctkin. Concrete Technician, Einstein<br />

Observat01y, Erich Mendelsohn Arch., Collaborator. Lectured on International Des ign at Gropius' Bauhaus, Dessau,<br />

two years. Head draftsm an for Le Corbusier, Paris, six years 35<br />

72<br />

SSAC BULLETIN 19:3

Endnotes<br />

For example, the question is not discussed in the valuable<br />

study of Modernist design in Toronto compiled<br />

by Detlef Mertins, Marc Baraness, Ruth Cawker,<br />

Brigitte Shim, and George Kapelos, Toronto Modem:<br />

Architecture 1945-1965 (Toronto: Bureau of Architecture<br />

and Urbanism and Coach House Press, 1987).<br />

The standard literature on Modernism, epitomized by<br />

the excellent books of William J.R. Curtis and<br />

Kenneth Frampton, respectively Modem Architecture<br />

Since 1900, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Phaidon, 1991) and<br />

Modem Architecture: A Critical History (Toronto:<br />

Oxford University Press, 1980), is equally bereft of<br />

such an analysis. Some discussion of the broader issue<br />

of changes in professional and popular taste appears<br />

in Paul Greenhalgh, ed., Modernism in Design (London:<br />

Reaktion, 1990). The author is grateful to the<br />

archivists and librarians at the universities of British<br />

Columbia, Calgary, Manitoba, and Toronto for their<br />

assistance. A special debt of gratitude is owed to<br />

Kathy Zimon, Catherine Fraser, and Ouita Murray of<br />

the Canadian Architectural Archives at Calgary. Part<br />

of this research was funded under a grant from the<br />

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of<br />

Canada.<br />

2 The emergence of Modernism in Vancouver has been<br />

charted brieny by Harold Kalman, most recently in<br />

the third edition of Exploring Vancouver (Vancouver:<br />

UBC Press, 1993) written with Ron Phillips and<br />

Robin Ward, and by Douglas Shadbolt in "Post-war<br />

Architecture in Vancouver," in Vancouver, Art and<br />

A rtists, 1931-1983, L. Rombout. ed. (Va ncouver:<br />

Vancouver Art Gallery, 1983): 108- 11 9. The existence<br />

of a distin ct regional domesti c Modernism is<br />

proposed by Sherry McKay, "Western Livin g, Western<br />

Homes," SSACBulletin 14, no. 3 (September 1989):<br />

65-74. The broader innuences upon B.C. architecture<br />

• arc outlined in Janine Bond, University EndoM•nent<br />

Lands Architecture 1940-1969 (Vancouver: Heritage<br />

Vancouver Society, 1993).<br />

3 These developments are summarized in Patricia E.<br />

Roy, Vancouver, An Rlustrated History (Toronto: J.<br />

Lorimer, 1980) and G raeme Wynn and Timothy Oke,<br />

eds., Vancouver and its Region (Vancouver: UBC<br />

Press, 1992). The socio-cultural context is recounted<br />

by A Bat kind, "On Ferment and Golden Ages," and<br />

by Arthur Erickson, "To Understand the City we<br />

Make," in Vancouver Forum 1: Old Powers, New<br />

Forces, Max Wyman, ed. (Vancouver: Douglas &<br />

Mcintyre, 1992): 63-79, 146-159. A connuence of<br />

broader, chieny professional, social and Modernist<br />

architectural values is argued by this author in<br />

"Schools for the 'Brave New World': The School<br />

Architecture of Thompson, Berwick and Pratt," B.C.<br />

Studies 90 (Summer 1991): 25-39, and "The Culture<br />

of Modernism: Vancouver's Public Libraries 1947-<br />

1957," Architecture + Culhtre: The Proceedings of the<br />

lntenrational Research Symposium at Carleton University<br />

(Ottawa: Carleton University, 1992): 358-36 1.<br />

4 The author has discussed this period with the maj ority<br />

of the living members of the post-wa r generation who<br />

practised out of Vanco uver, as well as those involved<br />

in co nstruction and lumber manufa cture, toward a n<br />

exhibition, Vancouver: The Spirit of Modernism, organized<br />

under the auspices of the Ca nadian Centre for<br />

Architecture, to open in 1996.<br />

5 Modernist concern with regional and ethni c fa ctors<br />

was increasingly voiced at the post-war conferences of<br />

C. I.A.M., as recounted inS. Giedion, A Decade of<br />

New Architecture (New York, 1954), 1-2. Nevertheless,<br />

it is worth recalling Lubetkin's 195 1 comment abo ut<br />

the Spa G reen Estate, London. 1949: "For too long.<br />

architectural solutions were regarded in terms of<br />

abstract principles, with formal expression left to itself<br />

as a fun ctional resultant. The principles of composition,<br />

the emotional impact of the visual were brushed<br />

aside as irreleva nt. Yet this is the very material with<br />

which the architect operates .... " Quoted in Anthony<br />

Jackson, The Politics of Architecture: A History of<br />

Modem Architecture in Britain (Toronto: University of<br />

Toronto Press, 1970), 170. For B.C. Binning. Modernism<br />

was altogether more positive. In "The ~rtist and<br />

the Architect," Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute<br />

of Canada [JRA/Cj 27, no. 9 (September 1950):<br />

320-21 , he wrote: "As for Canada, generally speaking<br />

it is only since the war that Artist and Architect have<br />

felt the need for new forms to express the new thought<br />

and feeling within our country." That dimension is<br />

studied in Denise Leclerc, The Crisis of Abstraction in<br />

Canada: The 1950s (Ottawa: National Gallery of<br />

Canada, 1992).<br />

6 An obvious example of the ideological diversity within<br />

Modernist thought can be found in the contrasting<br />

views on the architect and society propounded by<br />

Karel Tiege and by Le Corbusier; see Jean-Louis<br />

Cohen, Le Corbusier and the Mystique of the USSR·<br />

Theories and Projects for Moscow, 1928-1932 (Princeton,<br />

N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1991). In "The<br />

Case for a Theory of Modern Architecture," R.I.B.A.<br />

Joumal64 (June 1957): 307-18, John Summerson<br />

questioned the existence of a distinct Modernist<br />

theory. However, to most students from this period,<br />

Modernism seemed to afford a pragmatic and<br />

efficient approach to contemporary design problems.<br />

That interpretation is corroborated by the first issues<br />

of the University of Manitoba School of Architecture<br />

student magazine TecsandDecs. E.W. G lenesk (with<br />

a typical assumption of theoretical clarity) wrote on<br />

the development of twentieth century architectural<br />

design in the 1948 issue: "Modern design provides<br />

integration of our mode of life with the planning of a<br />

building. integration between architects, artist. and<br />

sculptor. Modern design is clean, honest. devoid of<br />

falsity and imitation, is fun ctional, bea utiful, organic<br />

and integrated." The 1949 issue, moreover, underscores<br />

the general absence, among the first generation<br />

of Canadian Modernists at least. of intellectual obsequiousness;<br />

under a caricature of Le Corbusier's<br />

domestic architecture is the caption: "L.E. Koroyousae.<br />

Architect-Knailem Inc. Builders. Home of the Year."<br />

7 Biography in Leclerc, 87-88; see also Shad bolt, 108-<br />

110.<br />

8 Nevertheless, Erickson would comment of the house<br />

he designed with Geoffrey Massey in 1955 for Ruth<br />

Killam in West Vancouver (Massey Silver Medal,<br />

1956): "Our design was a blend of Bauhaus form al<br />

concepts with West Coast sensibility to wood construction.<br />

" Catalogue, Arthur Erickson Exhi bition,<br />

Vancouver Art Gallery, 1966 (copy in the Canadian<br />

Architectural Archives, University of Calgary).<br />

9 Omitting the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Montreal, which<br />

maintained the Fren ch Beaux Arts system well into<br />

the 1950s, the university ca lendars demonstrate that<br />

the study of Modernist the01y and design was introduced<br />

ea rliest at Toronto (from about 1933. according<br />

to Bill Bi rmingham), but wi thout the more genera l<br />

change in academic initiated at McGill from 1940-41.<br />

The situation did not alter at Manitoba until after<br />

1946, when John Russell (appointed Head only in<br />

1948) was joined by Modernists such as Wolfgang<br />

Gerson. Architecture was, for ex.1mple, still described<br />

as a "fine art" until 1945 -46, when the architect was<br />

defined as a "planner and builder ... providing for<br />

human fun ction." In terms of text books, Manitoba<br />

continued to recommend Bannister Fletcher's A History<br />

of Architeclure otrthe Cotnparative Method until 1954,<br />

when it was replaced by Talbot Hamlin's Architeclrue<br />

Through tlreAges (New York: Putnam, 195 1), which addressed<br />

the Modern movement Even at McGill, the<br />

Modernist litera lure such as Giedion's Space, Time<br />

and A rchitecture: The Growth of a New Tradition<br />

(Ca mbridge: Harvard University Press, 194 1), F.R.S.<br />

Yorke and Colin Penn's A Key to Modem Architecture<br />

(London and Glasgow: Blackie & Son, 1938), and J.M.<br />

Richard's An Introduction to Modem Design (London,<br />

1940) was at first only included on the summer reading<br />

lists. At Toronto, F.R.S. Yorke's The Modem<br />

House in England (London: The Architectural Press,<br />

1935) and Le Corousier Towards a New Architecture<br />

were on the course bibliography from 1940, although<br />

Giedion's Space, Time and Architecture was not included<br />

unti11945. Students obviously acquired their<br />

own collection of books and magazines, typified by<br />

Bill Birmingham subscribing to Architectural Review<br />

through the 1930s, or Roy Jessiman purchasing].<br />

McAndrew and E. Mock's What is Modem Architecture?<br />

(New York: Museum of Modern Art. 1946).<br />

10 The renown quickly achieved by Vancouver Modernist<br />

design is further indicated by the organization in<br />

1949 of an exhibition of recent West Coast work by<br />

the Architectural Society of the Toronto School under<br />

the direction of Ian MacLennan, and by the publication<br />

of an article on C.E. Pratt's Brooks house in West<br />

Vancouver (1946-47; demolished) in Architectural<br />

Record (October 1948): 97-101.<br />

II "Aphorisms on Architecture and Form," G2 (1923),<br />

reprinted in Philip C. Johnson, Mies van der Rohe, 3rd<br />

ed. (New York, 1978), 189, preceded by the sen tence,<br />

"We refuse to recognize problems of form, but only<br />

problems of building. " Gropius's statement comes<br />

from his The NewArchitech.re and the Bauhaus, trans.<br />

P. Morton Shand (London, 1937), 7. See also his article<br />

"Towa rd a Living Architecture," American Architect<br />

and Architecture (January 1938): 21-22: "A true<br />

Modern architect. that is to say, an architect who tries<br />

to shape our new conception of life, who refuses to<br />

live by repeating the forms and ornaments of our<br />

ancestors, is constantly on the lookout for new means of<br />

enriching his design in order to enliven the starkness<br />

and rig our of the early examples of the architectonic<br />

revolution."<br />

12 Erickson, Vancouver Forum I.<br />

131n an un published lecture dating from aboutl945 and<br />

kindly made avai lable by his widow, Gerson explained<br />

his admiration for Le Corbusier (and Modernist<br />

practice generally), stating that he had "succeeded in<br />

spreading the gospel of a truly new plastic art, based<br />

on the techni cal resources of our day, and has clearly<br />

shown how art must and will again become part of<br />

everyday life, without the need of lowering artistic<br />

standards through the means of the applied plastic<br />

arts."<br />

14 Coates's advocacy of Modernism is effectively<br />

reviewed in Sherban Canta cuzino, Wells Coates, a<br />

Monograph (London: G. Fraser, 1978). Cantacuzino<br />

also covers the Canadian schemes Coates worked on<br />

during the 1950s, ending with three projects for<br />

Vancouver. including the "Project '58" redevelopment<br />

proposa l. Coates's papers are now at the<br />

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal. Contemporary<br />

British urban design, closely monitored in<br />

Canada, is covered effectively in John Summerson,<br />

Ten Years of British Architecture '45- '55 (London,<br />

1956).<br />

15 The choice of Lasscrrc was made by Dr. Norman<br />

MacKenzie, president of the University of British<br />

Columbia, but only after Peter Cotton and a group of<br />

veteran undergraduates won the support of the professional<br />

bodies representing the local contractors and<br />

architects as well as the lea ding Vancouver Modernists,<br />

including Pran and Berwick. Information derived from<br />

the unpublished three-volume scrapbook of the School<br />

of Architecture, U.B.C Special Collections.<br />

16 Some indica tion of his contribution to the Ca nad ian<br />

architectural profession is recounted in Irena Murray<br />

and Norbert Schoenauer, eds., John Bland at Eighty:<br />

A Tribute (Montreal: McGill University, 1991).<br />

19:3<br />

SSAC BULLETIN<br />

73

17 Information based on discussions with Bland, Chard<br />

Wisnicki, and McNab.<br />

18 Lyle's article, published in the March 1932 issue of<br />

theJRA/C, is quoted in Geoffrey Simmins, Documents<br />

in Canadian Architecture (Peterborough, Ont: BroadviewPress,<br />

1992), 158. Waters's broadcast was<br />

reprinted in JRAIC 13, no. 3 (March 1936): 49.<br />

19 Torontonensis, 1937, p. 295.<br />

20 Information kindly supplied by Thornton, who in 1938<br />

worked with Birmingham in the Vancouver office of<br />

C.B.K. Van Norman, together signing at least one of the<br />

working drawings preserved at the Vancouver City<br />

Archives for Van Norman's Modernist house on West<br />

61stAvenue (demolished in February 1994).<br />

21 "Bridging the Gap in an Ever Changing Environment,"<br />

JRA/C 37, no. 7 (July 1960): 299-300. The<br />

theoretical foundation and objectives of the McGill<br />

curriculum were nicely defined by two former<br />

students writing in John Bland at Eighty: David Burke,<br />

who graduated in 1957, noted the respect accorded to<br />

Mies, Le Corbusier, and Gropius, but also to F.L.<br />

Wright and E. Saarinen, adding "The Modern movement<br />

was well entrenched at McGill ... Yet John and<br />

his staff ensured that the educational process never became<br />

doctrinaire"; Moshe Safdie, whose graduating<br />

thesis formed the basis for the Expo '67 Habitat apartments,<br />

recalled the "sense of Architecture for the common<br />

cause, architecture as the art of building, rooted<br />

in the technology of construction and forever in<br />

search of the appropriate interpretation of programme<br />

and purpose and its imprint on the spatial organization<br />

of the building."<br />

22 Apart from the stress laid upon spiritual and aesthetic<br />

ma tiers in Le Corbusier's Towards a New Architech.rc,<br />

Gropi us averred in The Scope of Total Architecture,<br />

3rd ed. (New York: Collier, 1966), 60, that<br />

"rationalization [was] only [Modernism's] purifying<br />

role. The other aspect, the satisfaction of the human<br />

soul, is just as important as the material." At the 8th<br />

C. LAM. conference at Bridgewater, England, in<br />

1947, the delegates (originally to include Douglas<br />

Simpson) reiterated their objective "to work for the<br />

creation of a physical environment, that will sa tisfy<br />

man's emotional and material needs and stimulate his<br />

spiritual growth." Quoted in Giedion, Decadeof<br />

ModemArchitech.re, 12.<br />

(New York: Rizzoli/CBA, 1992).<br />

27 Ibid. , 20.<br />

28 Mies's quip is quoted in David A Spaeth, Mies Van<br />

Der Rohe (New York: Rizzoli, 1985), 19.<br />

29 Arthur published a photograph of Mendelsohn's own<br />

house at Rehoboth in the January 1938 issue ofJRA/C.<br />

30 Chitty's house had also been illustrated in the<br />

February 1938 issue of the Architectural Review.<br />

Photographs of the Simon House are preserved in a<br />

bound typescript autobiography kindly made available<br />

by Mrs. Gerson, which also includes illustrations of<br />

his own more radical Modernist house, "Wildwood,"<br />

erected in 1950 on South Drive, Winnipeg.<br />

31 In 1937, L'Architecture illustrated domestic architecture<br />

by B. Taut, M. Fry, G . Samuel, as well as R<br />

Schindler, together with (in October) Alvar Aalto's<br />

Viipuri Library. In 1938 it would also carry<br />

photographs of Howe and Lesaze's P.S.F.S. Building<br />

in Philadelphia and Tecton's Highpoint I Flats in<br />

London, in addition to houses by Soriano and Harris<br />

plus a report on the M.A.R.S. London exhibition.<br />

32 The design objectives of these architects were widely<br />

publicized throughout James and Katherine M. Ford's<br />

The Modem House in America (New York: Architectural<br />

Book Pub., 1940), including direct statements by<br />

Wurster, Belhuschi, Harris, and Sorriano, who<br />

commented interestingly (p. 126): "There is no such<br />

thing as a distinctly American modern architecture<br />

nor any other nationality. All serious works of art are<br />

international and not national."<br />

33 Information kindly supplied by Nathan Nemetz.<br />

34 McKay, 72. The comment was made about such of his<br />

conceptually different and already neo-Wrightian<br />

houses as that commissioned via Sharp & Thompson,<br />

Berwick, Pratt by Dr. Harold Coppin 1950 (1952<br />

Massey Silver Medal).<br />

35 TorontoneiiSis, 1939, p. 129. The author was Jacob<br />

Sugarman, who later had a distinguished career in<br />

Ontario.<br />

23 Arthur, trained at the University of Liverpool and in<br />

the office of Sir Edwin Lutyens before being appointed<br />

to the University of Toronto in 1923, defined his<br />

idea of Modernism in a February 1936 CBC talk,<br />

"How to Appreciate Architecture," reprinted in the<br />

December 1936 JRAIC: "We live in a machine age and<br />

are o nly now beginning to see that modern materials<br />

and construction have an intrinsic beauty that needs<br />

no embellishment."<br />

24 ForTecton and brief references to Lasserre's<br />

presence there, see John Allan, Berthold Lubetkin:<br />

Architecture and the Tradition of Progress (London:<br />

RIBA Publications, 1992).<br />

25 Fred Lasserre, "Modern Architecture: The New<br />

Aesthetics and Cement," JRAIC 15, no. 6 (June 1938):<br />

145. In 1938, Arthur also published Modernist works<br />

by Raymond McGrath, Agnolo Mazzoni, Erich<br />

Mendelsohn, Connell Ward and Lucas, J.B. Parkin<br />

(in August, a rather diluted brick Modernist house in<br />

Croydon), Richard Neutra, and the pioneering eastern<br />

Ca nadian Modernist Greenshields house in Montreal<br />

by Ernest Barott. In 1937 he selected several British<br />

Modernist buildings, including a villa at Frinto n by<br />

Oliver Hill and the Quarry Hill Flats at Leeds by<br />

R.A.H. Livett, and printed an advertisement for<br />

Yorke's Modem House in England.<br />

26 The ideologica l context of the exhibition is explored<br />

in Terence Riley, The lntemational Style: Exhibition 15<br />

and the Museum of Modem Art, Stephen Perella, ed.<br />

Rhodri Windsor Liscombe is a professor in the<br />

Department of Fine Arts at the University of British<br />

Columbia, Vancouver. His most recent publication is<br />

Altogether American: Roben Mills, Architect and<br />

Engineer, 1781-1855 (New York: Oxford University<br />

Press, 1994).<br />

74<br />

SSAC BULLETIN t9:3

Letters<br />

II July 1994<br />

I noticed your piece on Canadian architectural<br />

periodicals in the most recent SSAC Bulletin, but<br />

saw no mention there of the earliest periodical I've<br />

come across, The Canadian Builder and Mechanics<br />

Magazine. It would appear that this long-forgotten<br />

publication, of which only one copy is known to exist in<br />

public collections, may claim the distinction of being<br />

the first monthly magazine in its subject field to<br />

issue from Canadian presses.<br />

On 3 February 1869 the London Free<br />

Press reported the appearance of the first number<br />

of The Canadian Builder, published by Thomas<br />

Dyas. In March 1869 the second number, published<br />

by the firm of Dyas and Wilkins, was noted in a<br />

Philadelphia periodical, The Architectural Review<br />

and American Builders' Journal. 1 Almost a year later,<br />

in February 1870, it described the January issue as<br />

wonderfully improved: "For fifty cents a year it gives<br />

twelve numbers filled with material useful and interesting,<br />

original and select, with engravings." 2<br />

The Dyas and Wilkens partnership was<br />

established in l.Dndon, Ontario, in late February,<br />

1869. 3 A l.Dndon directory for that year lists the firm of<br />

Dyas and Wilkens as architects and patent agents on<br />

Richmond Street. Wilkens was also a partner in Teale<br />

and Wilkens, marble and stone dealers. 4 Thomas W.<br />

Dyas and Henry A Wilkens dissolved their partnership<br />

on 29 Apri11870. 5 Dyas continued to publish 77ze<br />

Canadian Builder for only a brief while longer before<br />

selling it to Bell, Barker & Co., a Toronto printing and<br />

publishing firm, in whose ownership the periodical is<br />

thought to have expired after M ay, 1871. 6<br />

Thomas Winning Dyas was born in Ireland<br />

on 2 September 1845, one of seven children. His<br />

father John Dyas brought the family from Ireland to<br />

New Orleans about 1850 and then to London,<br />

Canada West, in 1859. 7 Thomas Dyas trained as a<br />

land surveyor and qualified for his profession in<br />

1865, when he was living at Bothwell, Canada<br />

West. 8 He is said to have moved to Toronto the<br />

following year and entered into partnership with<br />

Charles Unwin and C.C. Forneri. In 1868 Dyas<br />

returned to live in London.<br />

Thomas Dyas had a strong interest in<br />

writing and publishing. Not only does he appear to<br />

have been the moving force behind The Canadian<br />

Builder, but in 1872-74 he contributed to 171e Fanners'<br />

Advocate, an agricultural newspaper in London where<br />

his father was assistant editor. The younger Dyas's<br />

literary interests came to dominate his professional<br />

activity in 1875, when he left surveying and took a job<br />

in Toronto as superintendent of agencies for The<br />

Globe newspaper. In 1878 he joined 17u Mail, where<br />

he held various posts as manager of the business, advertising,<br />

and circulation departments until his death<br />

on 22 June 1899. It is of some interest that his eldest<br />

daughter continued the family's links to publishing<br />

when she married Hugh C. Maclean, editor of The<br />

Contract Record and brother of James Bayne<br />

Maclean, founder of Maclean Hunter.<br />

1be National Library of Canada holds a<br />

single copy of The Canadian Builder and Mechanics<br />

Magazine, val. 1, no. 4 (1 May 1869). This eightpage<br />

unillustrated issue is the only complete number<br />

known to have survived. In addition, a single article<br />

with illustrations was reprinted and reproduced in the<br />

April 1870 issue of The Architectural Review and<br />

American Builders' Journal. Charles F. Damoreau,<br />

who engraved an elevation and plan illustrating the<br />

article, was active in Toronto as a designer, artist,<br />

and engraver on wood from 1864 to 1871. 9<br />

Stephen A. Otto<br />

Toronto<br />

I. 77Je Arcltitec/ural Review [a !so known as Slcan 's Arcltitectural<br />

Re>•iew after its founder and editor, Samuel Sloan, a Philadelphia<br />

architect], vol. I, p. 608. The Canadian magazi ne was also noted<br />

in theLondo11Advertiser, 13 October 1869, and was reported to<br />

still be in publication by the London Free Press, I March 1870.<br />

2./bid, vo l. 2, p. 494.<br />

3. London Free Press, 26 February 1869, p. 2.<br />

4. Province of Ontario Gaze/leer and Directory (Toronto:<br />

Robertson and Cook, 1869).<br />

5. London Free Press, 30 April 1870. Dyas carried on as an architect<br />

an d engineer with offices opposite the Canadian Bank of<br />

Comm erce (London Free Press, 10 May 1870 et seq.). Wilkens<br />

became foreman at J.W. Smyth's marble works (London Free<br />

Press, 4 May 1870).<br />

6. Robertson & Cook 's Toronto City Directory for 1871-2 (Toronto:<br />

Daily Telegraph Priniting House, [May)1 871), opp. p. 112.<br />

7. Report of the Association of Ontario Land Surveyors, 1924.<br />

8. Canada Classified Directory (Toronto: Mitchell and Co., 1865-66).<br />

9. J. Russell Harper, Early Painters and Engravers in Canada.<br />

"Institution for the Deaf and Dumb,<br />

Belleville, Canada," engraved by<br />

[C. F.] Damoreau, Toronto, and<br />

reprinted from the Canadian<br />

Builder in The Architectural<br />

Review and American Builders'<br />

Journal, Apri/1870, p. 589.<br />

19:3<br />

SSAC BULLETIN<br />

75

Math Jeshurun (1904)<br />

Agudath Achim (1912)<br />

Machzikey Hadas (1926)<br />

D<br />

B'nei Jacob (1931)<br />

76 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 19:3

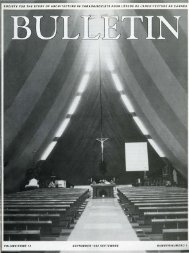

The First Synagogues<br />

in Ottawa<br />

J J" ~ile some Jews were living in Ottawa almost from its establishment as the capital of Canada, the Jewish community<br />

r r i~ this city began in earnest in the 1880s, when groups of Jews arrived in Ottawa as part of the wave of emigration<br />

from Czarist Russia. 1<br />

In Eastern Europe, prayer services were an integral part of the traditional Jewish Orthodox lifestyle, and therefore<br />

it was vital for the early immigrants to have religious services. For these immigrants- many of whom were impoverishedarriving<br />

in the new world and having to learn a new language and adjust to a strange and challenging environment, the<br />

synagogue served, at least initially, as a comforting link with the world they had left behind.<br />

Since Jewish law defines a synagogue as any place where a quorum of ten males over the age of 13 (a minyan)<br />

gathers to worship, early congregations in the new world typically began with individuals meeting in private homes. This practice<br />

reflected the tradition of the Shteb/s, or unpretentious prayer rooms. Later, they would rent a space until enough money<br />

was saved to buy land to build their own building.<br />

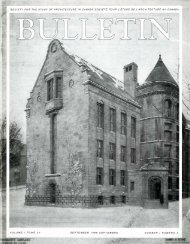

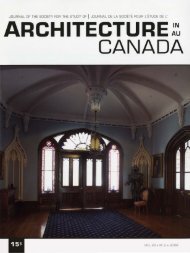

The tight-knit quality of the community and the focused origin of congregants gave rise to the architectural<br />

homogeneity of the first synagogues in Ottawa, Adath Jeshurun (1904), Agudath Achim (1912), Machzikey Hadas (1926),<br />

and B'nei Jacob (1931) (figure 1 ). These buildings were modelled after Eastern E uropean synagogues, which employed the<br />

Romanesque style embellished with Byzantine details. At the end of nineteenth century the Gothic style had become strongly<br />

associated with Christianity, and Romanesque was chosen for Canadian synagogues because of its close links to the Eastern<br />

European homeland of the Jewish communities. 2<br />

b y H a g t<br />

H<br />

a d a y a<br />

Figure 1. The first four synagogues in Ottawa.<br />

(Hagit Hadaya, 1994)<br />

19:3<br />

SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 77

Figure 2 (above). Schematic plan and section of an<br />

Eastern European synagogue. (Hagit Hadaya, 1991)<br />

Figure 3 (right). Adath Jeshurun Synagogue (1904),<br />

375 King Edward Street, Ottawa, Ontario; front<br />

elevation. (R. Schingh Collection, Ottawa Jewish<br />

Historical Society)<br />

I This description of Ottawa's first synagogues is based<br />

on a paper presented at the SSAC conference in June<br />

1994. It is excerpted from my Master's research essay<br />

"In Search of Sacred Space: The Architectural History<br />

of the Synagogue in Ottawa, 1892 to the Present"<br />

(Carleton University, 1992).<br />

2 Isaac Levy, The Synagogue: Its History and Function<br />

(London: Valentine, Mitchell, 1963), 36.<br />

3 Sheldon Levit~ Lynn Mils tone, and Sidney T.<br />

Tenenbaum, Treasures of a People: The Synagogues of<br />

Canada (foronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1985), viii.<br />

4 R. Schingh, "Architecture and Ethnic Groups: The<br />

Ottawa Region Jewish and Italian Communities,"<br />

Research and Development Project 80-461 (1981),<br />

15, Carleton University.<br />

5 Abraham Lieff, Gathering Rosebuds (foronto: Gall<br />

Pa pen burg Computer Systems, 1986), I 0.<br />

6 John H. Taylor, Ottawa: An Illustrated History, The<br />

Histmy of Canadian Cities (foronto: James Lorimer<br />

and the Canadian Museum of Civilization 1986), 124.<br />

7 HermanS. Rood man, The Ottawa Jewish Community:<br />

An Historical Chronicle of Our Community for the Years<br />

1857-1987, 5617-5447: One hundred and thirty years of<br />

progress and achievement in the annals of Ollawa Jewry<br />

(Onawa: Jewish Community Council of Ottawa, 1989), I.<br />

8 Shirley E. Woods, Ottawa: The Capital of Canada<br />

(foronto: Doubleday, 1980), 182.<br />

9 Rood man, 2.<br />

10 Woods, 182.<br />

Synagogues before the Second World War were commonly built on tight urban<br />

residential lots. The placement of these buildings created a uninterrupted connection between<br />

the street and the sanctuary, with the latter typically located half a storey above street<br />

level (figure 2). This elevated main floor made it possible to have a social hall and/or a study<br />

hall on the lower level, with windows for natural light. Since the congregations at the time<br />

were Orthodox and required a separate seating section for women, the second floor generally<br />

served as the women's gallery. This wrapped around the north, west, and south walls, allowing<br />

for a two-storey cental space for the sanctuary itself and a visual axis to the Ark, placed at<br />

the east wall facing Jerusalem. (Although the practice of placing the Ark on the wall facing<br />

Jerusalem was a tradition, it never became a canon}<br />

Most of the early Jewish immigrants came from Latvia and Lithuania, 4 then part of<br />

Imperial Russia. The majority who arrived in Ottawa were Orthodox, and became peddlers<br />

or carried on small businesses of their own so they would not have to work on the Shabbat. 5<br />

The popular belief as to why Jews came to Canada's capital was that the cost of a peddler's<br />

permit was 10 cents rather than the $25 charged in other major centres. 6<br />

Jewish immigrants to Ottawa settled in the Lower Town area northeast of King Edward<br />

Avenue and Rideau Street. They probably chose this location because of its affordable<br />

housing and its proximity to the market, where goods for peddling could be obtained. By<br />

1889 there were 20 Jewish families settled in Ottawa, 7 enough to form a minyan. As was typical<br />

in the rest of Canada, Jewish worshippers in Ottawa followed the pattern of meeting first<br />

in one another's home, then renting space until enough money was saved to buy some land<br />

and build their own building. Services were first conducted in the homes of the leading members<br />

of the day, Moses Bilsky and John Dover, who were the first Jewish settlers in Ottawa.<br />

By 1892 the first congregation was formally formed, and adopted the name of<br />

Adath Jeshurun. The first synagogue building of this congregation was located at 264 Murray<br />

Street. A wooden structure to which a women's gallery was later added, this synagogue<br />

proved to be poorly located since it was near a food processor whose main product was pork<br />

and beans. During Shabbat services the odour of cooking pork carried into the synagogue.<br />

The odour itself was bad enough, but was doubly insulting to the congregation because,<br />

under Jewish law, the pig is considered an unclean animal. 8<br />

In addition to this problem, by 1901 the Jewish population in Ottawa had increased<br />

to 400 9 and the synagogue structure could no longer contain the great number of congregants.<br />

The synagogue's leaders began to plan a program for expansion of their facilities and<br />

purchased land for a larger house of worship. 10 A piece of land was acquired on King Edward<br />

78<br />

SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 19:3

Ill<br />

Ill<br />

I ll<br />

Avenue, and John W.H. Watts was commissioned to design the new structure. 11 Watts' symmetrical<br />

design for the front facade of Adath Jeshurun's building incorporated a large corbelled<br />

brick arch enclosing a pair of double doors, above which was a bank of five small<br />

arched windows, all bracketed by two slightly projecting stair towers capped with Moorish<br />

domes (figure 3). The windows followed the Romanesque tradition of rounded arches with<br />

radiating brickwork. The design of this facade resembled that of the original Holy Blossom<br />

Synagogue (now St. George's Greek Orthodox Church) on Bond Street in Toronto, designed<br />

by Benjamin Siddall in 1897 (figure 4), though the onion domes on Adath Jeshurun are<br />

smaller. (These two were the only synagogues in Canada to use Moorish domes to cap their<br />

stairs towers). 12 The roofline was changed in 1930 when a decorative parapet wall containing<br />

a circular window with a Magen David- Star of David- was added between the towers to<br />

hide the pitched roof (figure 5).<br />

The interior of the Adath Jeshurun Synagogue (figure 6) is reminiscent of Eastern<br />

European models in that it is a long and narrow barrel-vaulted room with a lower flat ceiling<br />

over the balcony. The balcony itself is horseshoe-shaped, and is supported on metal columns<br />

that rise to meet the wooden ribs of the ceiling. The Bimah or reading platform was originally<br />

on the main axis of the room, but was removed when the synagogue became the Hevra<br />

Kadisha, or funeral chapel.<br />

Agudath Achim, the second Orthodox synagogue, was begun at the turn of the century<br />

when a gentleman by the name of Myer Held began a minyan at his home on St. Patrick<br />

Street. 13 This served as a nucleus for the establishment of the Agudath Achim congregation.<br />

Increased immigration also played a role in promoting the founding of a new synagogue. This<br />

congregation's first structure was a converted double house on Rideau Street which accommodated<br />

75 male worshippers on the ground floor. A smaller number of seats for the women<br />

was available in the balcony. 14<br />

In 1910 another piece of land was purchased on Rideau Street, and the architectural<br />

firm of Burgess & Coyles was hired to design a building (figure 7). 15 These architects<br />

also adopted the Romanesque tradition of arched openings and radiating brickwork. The arched<br />

entrance consisted of a set of double doors above which were three round-headed leadpaned<br />

windows. The two secondary entrances were on the sides of the projecting central<br />

frontispiece, rather than flanking the main entrance as in Adath Jeshurun.<br />

At about the same time, and despite the fact that Adath Jeshurun and Agudath Achim<br />

were already in existence, another newly-arrived group of immigrants expressed a preference<br />

for their own house of worship and established the Machzikey Hadas congregation. 16 The<br />

Figure 4 (top). Holy Blossom Synagogue (1897),<br />

Toronto, Ontario; front elevation. (National Archives of<br />

Canada, RD 471)<br />

Figure 5 (left). Adath Jeshurun Synagogue (1904), 375<br />

King Edward Street; front elevation. (Hellmut Schade)<br />

Figure 6 (above). Adath Jeshurun Synagogue; interior.<br />

(S. Levitt, L. Milstone, and S. Tenenbaum, Treasures of<br />

a People: The Synagogues of Canada {Toronto:<br />

Lester & Orpen Oennys, 1985], 41)<br />

11 "Corner Stone Laid," The 01/awaJounra/, 25 July<br />

1904, 10. John William Hurrell Watts (1850-1917), a<br />

notable Ottawa architect, was born and trained in<br />

England. He had worked for the Chief Dominion<br />

Architect for 23 years before establishing his own<br />

practice in 1897. See Rhys Phillips, "Boastful<br />

Mansions by Architect John W.H. Watts," The Ouawa<br />

Citizen, 29 January 1994, Fl.<br />

12 Harold D. Kalman, The Conservation of Ontario<br />

Churches: A Programme for Funding Religious<br />

Properties of Architectural and Historical Significance<br />

(Toronto: Ministry of Culture and Recreation and<br />

Ontario Heritage, 1977), I 13.<br />

13 Agudath Achim Finding Aid, RG 5 A 02, Ottawa<br />

Jewish Historical Society.<br />

14lbid.<br />

15lbid.<br />

16 Rood man, 2.<br />

19:3 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC<br />

79

Figure 7. Agudath Achim (1912) , 417 Rideau Street,<br />

Ottawa, Ontario; front elevation. (Ottawa Jewish<br />

Historical Society 5-062)<br />

17 Mr. Laibel Steinberg, inteJView by Sam Brozovsky,<br />

1973, transcript, p. I, Ottawa Jewish Historical<br />

Society.<br />

18 S. Max, "Retrospect and Prospect Presentation at<br />

Machzikey Hadas," dedication, !6 June 1974, 2<br />

19 Noffke's range of work was enormous during a career<br />

that spanned more than five decades, from 1908 to the<br />

early 1960s. See Halina Jeletzky and Barbara Sibbald,<br />

Faces and Facades: The Renfrew Architecture of Edey<br />

and Noffke (Renfrew, Ont.: Juniper Books for<br />

Heritage Renfrew, 1988), 31.<br />

20 S. Berman, "Murray Street Synagogue Murals<br />

Restored," press release, 1984.<br />

desire of new groups to assemble with people from the same place of origin was not uncommon.<br />

In Toronto, for example, the Anshei Kieve and Anshei Minsk congregations built their<br />

own synagogues in 1926 (Rodfey Shalom Synagogue) and 1930 respectively; the words "Anshei<br />

Kieve" and "Anshei Minsk" literally mean " people ofKieve" and "people of Minsk." The<br />