Selected US Ticks and Tick-borne Pathogens - tabpi

Selected US Ticks and Tick-borne Pathogens - tabpi

Selected US Ticks and Tick-borne Pathogens - tabpi

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The epidemiology of tick-<strong>borne</strong> disease is<br />

changing: ticks are moving into new areas <strong>and</strong><br />

are being linked to new diseases. VETERINARY<br />

FORUM talks with leading experts to update you<br />

on the problem.<br />

The tick population in the United States is exploding. Driven by socioeconomic<br />

factors, changing climate <strong>and</strong> an increase in the number <strong>and</strong><br />

distribution of wildlife hosts, ticks have successfully spread across the<br />

country, changing the l<strong>and</strong>scape of zoonotic diseases.<br />

Two ticks are particularly troublesome in the United States: Amblyomma americanum<br />

(the Lone Star tick) <strong>and</strong> Ixodes scapularis (the black-legged or deer tick).<br />

They have spread across nearly half of the country, overlapping in many states,<br />

<strong>and</strong> have been implicated in transmitting nearly a dozen infectious disease<br />

pathogens to both humans <strong>and</strong> animals.<br />

“Based on clinical evidence <strong>and</strong> the literature, there appears that at least two major<br />

tick species have exp<strong>and</strong>ed their ranges <strong>and</strong> even their density within those<br />

ranges over the past 15 to 20 years,” explains Michael W. Dryden, DVM, PhD, who is<br />

professor of veterinary parasitology at the Kansas State University College of Veterinary<br />

Medicine. “Those tick species are Ixodes scapularis in the eastern half of the United States,<br />

which is our major Lyme disease <strong>and</strong> human anaplasmosis vector, <strong>and</strong> Amblyomma americanum,<br />

which is a big ehrlichiosis vector.”<br />

B y M a r i e R o s e n t h a l , M S • E x e c u t i v e E d i t o r<br />

May 2007 | Veterinary Forum 45

Massive<br />

increase in the<br />

deer population<br />

over the past<br />

100 years<br />

Suburbanization<br />

bringing people,<br />

wildlife <strong>and</strong> ticks<br />

together<br />

I. scapularis has been reported from<br />

Minnesota to Miami <strong>and</strong> from Bangor,<br />

Maine, to Corpus Christi, Texas, <strong>and</strong> A.<br />

americanum has been found from Corpus<br />

Christi to southern Michigan <strong>and</strong> from<br />

southern Florida to Maine, according to<br />

Dryden.<br />

Katherine M. Kocan, PhD, agrees,<br />

adding that the rise in the role of A.<br />

americanum has been one of the most<br />

fascinating aspects of her field of study.<br />

“Historically, the Lone Star tick, or A.<br />

americanum, was considered insignificant<br />

as a vector of disease, but now it is considered<br />

the number one vector. It used<br />

to be if someone got a Lone Star tick on<br />

them, I’d say don’t worry, you don’t<br />

have any risk of disease,” says Kocan,<br />

who is regents professor <strong>and</strong> Walter R.<br />

Sitlington endowed chair of food animal<br />

research in the department of pathobiology<br />

at the Center for Veterinary<br />

Health Sciences at Oklahoma State University.<br />

”But in the past 15 years or so,<br />

the Lone Star tick has become our number<br />

one tick vector in the United States.<br />

I think it is one of the most interesting<br />

<strong>and</strong> dramatic things going on in the<br />

study of tick-<strong>borne</strong> diseases in the<br />

United States.”<br />

© Wolfgang Rücki, Svetlana Larina, Michael West, Mark/Shutterstock<br />

Source: CDC<br />

Dispersal of<br />

juvenile ticks by<br />

migratory birds<br />

VETERNARY FORUM<br />

Increase in<br />

outdoor<br />

recreational<br />

activities<br />

And then there were?<br />

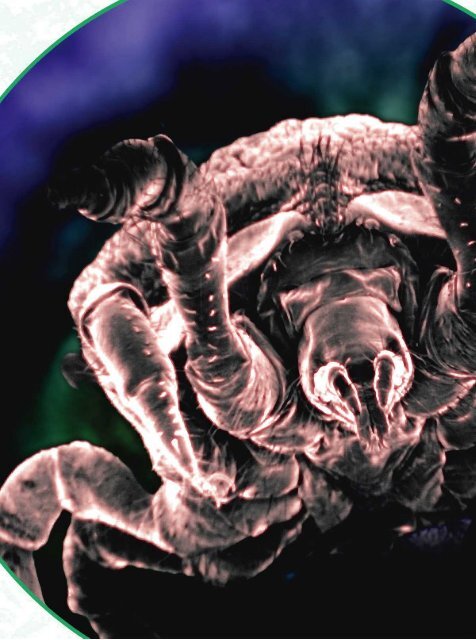

<strong><strong>Tick</strong>s</strong> are the most common transmitters<br />

of vector-<strong>borne</strong> diseases in the<br />

United States. They wait in vegetation for<br />

a host <strong>and</strong> then attach themselves using<br />

a hypostome to pierce the skin. During a<br />

blood meal, they transmit a variety of<br />

pathogens, including bacteria, spirochetes<br />

<strong>and</strong> rickettsiae.<br />

Most of the pathogens linked to A.<br />

americanum cause emerging diseases,<br />

Kocan explains, <strong>and</strong> the number associated<br />

with the tick has risen from zero to<br />

seven: Ehrlichia chaffeensis, which causes<br />

human monocytic ehrlichiosis; E. ewingii,<br />

which causes canine <strong>and</strong> human granulocytic<br />

ehrlichiosis; Francisella tularensis,<br />

the cause of tularemia; Rickettsia amblyommii,<br />

the cause of a rickettsial spotted<br />

fever that has not yet been named; non-<br />

46 Veterinary Forum | May 2007

pathogenic Theileria cervi in deer; <strong>and</strong> Borrelia<br />

lonestari, which has been associated<br />

with southern tick–associated rash illness<br />

(STARI), a newly described disease in humans.<br />

Another newly described disease<br />

that is associated with the Lone Star tick<br />

but does not yet have a name has been<br />

found in a goat in the United<br />

States <strong>and</strong> is caused by<br />

Ehrlichia ruminantium, which<br />

appears to be closely related<br />

to the pathogen<br />

that causes the African<br />

cattle disease known<br />

as heartwater.<br />

There are two other major tick vectors<br />

in the United States that are especially<br />

important for animal diseases: the brown<br />

dog tick <strong>and</strong> the American dog tick. Rhipicephalus<br />

sanguineus (the brown dog tick)<br />

transmits pathogens that cause the following<br />

canine diseases: Anaplasma platus,<br />

which causes a milder form of<br />

ehrlichiosis; Babesia canis,<br />

which causes babesiosis;<br />

<strong>and</strong> Ehrlichia canis, which<br />

causes canine monocytic<br />

ehrlichiosis. Outside<br />

the United<br />

States, the tick has<br />

Just because you did not diagnose this disease<br />

in your practice yesterday doesn’t mean you<br />

won’t diagnose it tomorrow.<br />

— Michael W. Dryden<br />

“In Africa, Ehrlichia ruminantium causes<br />

the cattle disease heartwater. It was reported<br />

in the Caribbean isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong><br />

Puerto Rico some years ago, <strong>and</strong> there<br />

is a big push to eradicate the tick from<br />

the Caribbean <strong>and</strong> Puerto Rico to reduce<br />

the risk of introducing heartwater<br />

into the United States. Heartwater is a<br />

major disease in cattle in Africa,” Kocan<br />

explains. “Just recently, a closely related<br />

Erhlichia organism was described<br />

in a goat in the Northeast.”<br />

I. scapularis transmits Anaplasma phagocytophilum,<br />

which causes human granulocytic<br />

anaplasmosis; Babesia microti, the<br />

cause of rodent babesiosis as well as human<br />

infection; B. odocoilei, which appears<br />

to be host-specific for deer (cervid<br />

babesiosis) <strong>and</strong> Borrelia burgdorferi, the<br />

cause of Lyme disease. These diseases<br />

occur in a variety of animals <strong>and</strong> humans<br />

(see charts on pages 50 <strong>and</strong> 52).<br />

been implicated in the transmission of<br />

Hepatozoon canis, which causes canine hepatozoonosis,<br />

<strong>and</strong> B. gibsoni, which causes<br />

babesiosis. The brown dog tick has also<br />

been implicated in the spread of Rickettsia<br />

rickettsii, the cause of Rocky Mountain<br />

spotted fever (RMSF) in both humans<br />

<strong>and</strong> dogs.<br />

Another vector of RMSF is D. variabilis<br />

or the American dog tick, which also<br />

transmits Anaplasma marginale, the cause<br />

of anaplasmosis in cattle; Cytauxzoon felis,<br />

the cause of cytauxzoonosis in domestic<br />

<strong>and</strong> wild cats; Ehrlichia canis, the cause of<br />

canine ehrlichiosis; <strong>and</strong> E. chaffeensis,<br />

which causes ehrlichiosis in humans <strong>and</strong><br />

dogs.<br />

Although it may seem as if ticks are<br />

being infected with more organisms,<br />

which is why they are transmitting more<br />

diseases, both Dryden <strong>and</strong> Kocan say<br />

that probably isn’t the case. Instead, re-<br />

48 Veterinary Forum | May 2007

searchers <strong>and</strong> epidemiologists have the technical means to<br />

find pathogens they couldn’t find before. “<strong><strong>Tick</strong>s</strong> are not changing<br />

their ability to transmit disease,” explains Dryden, “but we<br />

are recognizing more diseases because we are looking for<br />

them.”<br />

Adds Kocan: “Molecular technologies are fabulous. We<br />

can do things that we could never do before. For instance,<br />

you can collect ticks <strong>and</strong>, using polymerase chain reaction<br />

[PCR], you can test for half a dozen parasites at one time. So<br />

ticks may have carried these pathogens all along, but we<br />

just haven’t recognized them.”<br />

Because of tick spread, increased tick density <strong>and</strong> recognition<br />

of more diseases from tick vectors, veterinarians<br />

might find it useful to include vector-<strong>borne</strong> diseases that are<br />

not common in their area as part of the diagnostic differentials<br />

if the animal’s clinical signs <strong>and</strong> presentation match the<br />

disease definition. Dryden adds: “What I tell practitioners<br />

when I get in front of an audience is very simple: ‘Whatever<br />

you knew about ticks 5 years ago, it is different today <strong>and</strong><br />

whatever you know about ticks today will be different 5<br />

years from now.’<br />

“And that is because these ticks continue to move <strong>and</strong><br />

exp<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> increase in importance. Just because you did<br />

not diagnose this disease in your practice yesterday doesn’t<br />

mean you won’t diagnose it tomorrow. The situation is not<br />

static. This is a dramatic, dynamic situation we have today in<br />

the eastern half of the United States.”<br />

Hard ticks begin their life cycle as larvae, which hatch<br />

from eggs <strong>and</strong> immediately begin seeking hosts, often rodents.<br />

After the larvae successfully feed, they fall off the<br />

host <strong>and</strong> live in the soil <strong>and</strong> decaying vegetation where they<br />

then molt into nymphs, which seek their blood meal from a<br />

small vertebrate. If a nymph fails to find a blood meal, it<br />

dies. If it succeeds, it falls off the host <strong>and</strong> lives in the soil to<br />

molt into an adult. The adult seeks a larger host for its blood<br />

meal, <strong>and</strong> the preferred host for I. scapularis <strong>and</strong> A. americanum<br />

is the white-tailed deer, where the adult feeds <strong>and</strong> mates<br />

over the winter. The adult female tick is capable of laying<br />

several thous<strong>and</strong> eggs before she dies, according to Kocan.<br />

“The thing that drives the tick populations is deer. If we<br />

didn’t have deer, we wouldn’t have half the tick populations<br />

that we have,” Kocan says.<br />

When the United States was young, white-tailed deer<br />

flourished in this country, but they were over-hunted, explains<br />

Dryden. Through the 1800s, they were a major source<br />

of food in this country — even Army units supplied themselves<br />

by hunting deer. “The estimates indicate there were<br />

only between 200,000 <strong>and</strong> 300,000 white-tailed deer left in<br />

the early 1900s. Then it became illegal to hunt deer in many<br />

states,” Dryden says, as many state gaming departments<br />

tried to repopulate the species.<br />

(text continues on page 54)<br />

May 2007 | Veterinary Forum 49

<strong>Tick</strong> Species<br />

<strong>Selected</strong> <strong>US</strong> <strong><strong>Tick</strong>s</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tick</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> <strong>Pathogens</strong><br />

Pathogen(s) <strong>and</strong> Host(s)<br />

Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Disease/ Main Host(s)<br />

Common Name<br />

Amblyomma americanum Lone Star tick Borrelia lonestari Southern tick-associated Humans; deer<br />

rash illness (STARI)<br />

Ehrlichia chaffeensis Human monocytic Humans, deer<br />

ehrlichiosis (HME) <strong>and</strong> dogs<br />

Ehrlichia ewingii Canine granulocytic Dogs, deer <strong>and</strong><br />

ehrlichiosis in the humans<br />

United States<br />

Newly described; closely No disease name Goats<br />

related to Ehrlichia<br />

ruminantium, which causes<br />

the ruminant disease<br />

heartwater primarily<br />

in Africa.<br />

Francisella tularensis Tularemia Humans; rabbits,<br />

cats, other<br />

mammals<br />

Rickettsia amblyommii Spotted fever rickettsiae Humans <strong>and</strong><br />

group; no disease name other mammals<br />

Theileria cervi Nonpathogenic White-tailed deer<br />

Amblyomma maculatum Gulf Coast tick Ehrlichia ruminantium Experimental vector Cattle<br />

of heartwater disease<br />

in cattle<br />

Hepatozoon americanum Canine hepatozoonosis Dogs <strong>and</strong> coyotes<br />

in the United States<br />

Rickettsia parkeri No disease name Humans (?)<br />

Boophilus annulatus Cattle fever tick Anaplasma marginale Bovine anaplasmosis Cattle<br />

Babesia bigemina Bovine babesiosis or Cattle<br />

piroplasmosis<br />

Boophilus microplus Tropical cattle tick Anaplasma marginale Bovine anaplasmosis Cattle<br />

Babesia bigemina Bovine babesiosis or Cattle<br />

piroplasmosis<br />

Dermacentor albipictus Winter tick Anaplasma marginale Bovine anaplasmosis Cattle<br />

Dermacentor <strong>and</strong>ersoni Rocky Mountain Anaplasma marginale Bovine anaplasmosis Cattle<br />

wood tick<br />

Rickettsia rickettsii Rocky Mountain Humans <strong>and</strong> dogs;<br />

spotted fever (RMSF) rodent reservoir<br />

hosts<br />

(table continues on page 52)<br />

Credit: Katherine Kocan, Susan Little <strong>and</strong> Mason Reichard, Center for Veterinary Health Sciences, Oklahoma State University<br />

50 Veterinary Forum | May 2007

<strong>Selected</strong> <strong>US</strong> <strong><strong>Tick</strong>s</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tick</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> <strong>Pathogens</strong> (continued)<br />

<strong>Tick</strong> Species<br />

Pathogen(s) <strong>and</strong> Host(s)<br />

Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Disease/ Main Host(s)<br />

Common Name<br />

Dermacentor nitens Tropical horse tick Babesia equi Equine piroplasmosis Horses<br />

Dermacentor variabilis American dog tick Anaplasma marginale Bovine anaplasmosis Cattle<br />

Cytauxzoon felis Feline cytauxzoonosis Wild <strong>and</strong> domestic<br />

cats<br />

Ehrlichia canis Canine monocytic Dogs<br />

ehrlichiosis (CME)<br />

Ehrlichia chaffeensis Human monocytic Humans, dogs,<br />

ehrlichiosis (HME)<br />

<strong>and</strong> deer<br />

Rickettsia rickettsii Rocky Mountain Humans <strong>and</strong> dogs;<br />

spotted fever (RMSF) rodent reservoir<br />

hosts<br />

Francisella tularensis Tularemia Humans; rabbits,<br />

cats, other<br />

mammals<br />

Ixodes pacificus Western Borrelia Lyme disease Humans, dogs,<br />

Black-legged tick burgdorferi reptiles, rodents,<br />

birds<br />

Ixodes scapularis Black-legged tick Anaplasma Human granulocytic Humans <strong>and</strong><br />

phagocytophilum anaplasmosis (HGA) many reservoir<br />

hosts<br />

Babesia microti Rodent babesiosis Rodents <strong>and</strong><br />

Humans<br />

Babesia odocoilei Cervid babesiossis Deer<br />

Borrelia burgdorferi Lyme disease Humans, dogs<br />

<strong>and</strong> cattle; rodent<br />

reservoir hosts<br />

Rhipicephalus Brown dog tick Anaplasma platys* Milder form of Dogs<br />

sanguineus<br />

ehrlichiosis<br />

*Not confirmed<br />

**Not confirmed in the United States<br />

For references, please contact Marie Rosenthal at mrosenthal@vetlearn.com.<br />

Credit: Katherine Kocan, Susan Little <strong>and</strong> Mason Reichard, Center for Veterinary Health Sciences, Oklahoma State University<br />

Babesia canis Canine babesiosis Dogs<br />

Babesia gibsoni** Canine babesiosis Dogs<br />

Ehrlichia canis Canine monocytic Dogs<br />

ehrlichiosis (CME)<br />

Hepatozoon canis** Canine hepatozoonosis Dogs<br />

outside of the United States<br />

Rickettsia rickettsii Rocky Mountain Dogs <strong>and</strong> humans;<br />

spotted fever (RMSF) rodent reservoir<br />

hosts<br />

52 Veterinary Forum | May 2007

It was one of the most successful<br />

conservation efforts in history, <strong>and</strong> today,<br />

there are more than 30 million deer<br />

in this country. Humans also have eliminated<br />

the natural predators of deer, so<br />

they have flourished.<br />

“By anyone’s estimates, there are almost<br />

100 times the deer today than<br />

there was 100 years ago,” Dryden<br />

says. “I don’t care where you<br />

live, whether it is Kansas<br />

or New Jersey, when you<br />

were a kid, to see a<br />

deer was a phenomenon.<br />

Now they are<br />

everywhere, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

white-tailed deer is<br />

Other driving forces<br />

The other major driving forces behind<br />

the emergence of tick-<strong>borne</strong> diseases<br />

are the suburbanization of<br />

America; climate change; an increased<br />

incidence in outdoor recreational activities<br />

<strong>and</strong> migrating birds, according to<br />

the Centers for Disease Control <strong>and</strong><br />

Prevention (CDC).<br />

“You have changing trends in tick<br />

transmission <strong>and</strong> diseases because the<br />

environment <strong>and</strong> people are changing,”<br />

Kocan says. As people move from urban<br />

areas to suburbs <strong>and</strong> rural neighborhoods,<br />

they drive animals <strong>and</strong> their attached<br />

ticks to outlying areas moving<br />

them across the map.<br />

In addition, the trend today is not to<br />

cut forests to build tract houses but to integrate<br />

the homes with the natural surroundings.<br />

Although this is aesthetically<br />

pleasing, it brings people, wildlife <strong>and</strong><br />

ticks together. “Significant reforestation<br />

has occurred in the eastern United<br />

States over the past 100 years<br />

from massive clear cutting<br />

that occurred in the<br />

1700s <strong>and</strong> 1800s,” Dryden<br />

says. “We just are<br />

not doing that to the<br />

extent that we once<br />

did.”<br />

You have changing trends in tick transmission<br />

<strong>and</strong> diseases because the environment <strong>and</strong><br />

people are changing.<br />

— Katherine M. Kocan<br />

the primary host for adult I. scapularis<br />

<strong>and</strong> a major host for all stages of the<br />

Lone Star tick. Neither of those ticks can<br />

be maintained in high numbers in an<br />

ecosystem without white-tailed deer.”<br />

In addition, people are spending<br />

more recreational time outdoors, often<br />

with their dogs, providing another opportunity<br />

for ticks to attach. “Dogs are the<br />

ones that go out <strong>and</strong> run around <strong>and</strong><br />

bring ticks back into the human environment,”<br />

Kocan says. “I don’t think people<br />

underst<strong>and</strong> that dogs can be the big connector<br />

between people <strong>and</strong> ticks.”<br />

Migratory birds are also being recognized<br />

as both a host for various zoonotic<br />

pathogens <strong>and</strong> a carrier of ticks, which<br />

can drop off <strong>and</strong> lay eggs in new territory.<br />

According to a recent article in<br />

Emerging Infectious Diseases, North American<br />

birds host vector-<strong>borne</strong> pathogens,<br />

such as Anaplasma spp <strong>and</strong> B. burgdorferi,<br />

that infect Ixodes larvae. Although rodent<br />

species, such as the white-footed<br />

mouse, are the most common hosts of<br />

immature Ixodes ticks, alternative hosts,<br />

54 Veterinary Forum | May 2007

such as migratory birds, play a larger<br />

role than previously thought <strong>and</strong> may<br />

be hosts of epidemiologically important<br />

vector ticks.<br />

Finally, climate change is also influencing<br />

tick populations. “We are not<br />

experiencing as hard <strong>and</strong> as cold winters<br />

that we used to historically for<br />

whatever reason,” explains Dryden.<br />

“We need to protect ourselves <strong>and</strong> our<br />

dogs <strong>and</strong> cats. With the winters not being<br />

as hard as they used to be in many<br />

areas, we’ve gone to year-round tick<br />

control for our pets.”<br />

Although the winters didn’t necessarily<br />

kill ticks, they stopped attaching<br />

during the really cold months. Now, as<br />

soon as there is a sunny day, they are<br />

out again.<br />

“We have ticks all year-round,” explains<br />

Kocan from Oklahoma, “<strong>and</strong> each<br />

tick has its own biology <strong>and</strong> its own seasons.<br />

So, this time of year, we have the<br />

Lone Star tick, <strong>and</strong> by the end of the<br />

summer, it is I. scapularis, <strong>and</strong> then later,<br />

the Dermacentor albipictus comes out.<br />

“People think they only need tick<br />

control in the summer, but we have<br />

something out there all year around.<br />

Oklahoma has really become a hotspot<br />

for tick-<strong>borne</strong> diseases.”<br />

Although tick-<strong>borne</strong> diseases <strong>and</strong><br />

ticks are a major problem in the Northeast,<br />

South <strong>and</strong> Midwest, it doesn’t<br />

mean the West is without a tick problem,<br />

according to Curtis Fritz, DVM,<br />

MPVM, PhD, DACVPM (epidemiology)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Anne Kjemtrup, DVM, MPVM, PhD,<br />

both of the vector-<strong>borne</strong> disease section<br />

of the California Department of<br />

Health Services.<br />

“There are changes in tick densities<br />

<strong>and</strong> numbers yearly, but we don’t see an<br />

overall increase or change in location as<br />

they are seeing in other parts of the<br />

country,” Kjemtrup says. People moving<br />

into rural or coastal areas encounter more<br />

wildlife <strong>and</strong> ticks, but most transmission<br />

occurs through recreational activities.<br />

“We developed differently out here,”<br />

she says. “People live in high-density<br />

© iStockImages<br />

areas, where they don’t end up with<br />

large backyards. <strong>Tick</strong>-<strong>borne</strong> diseases in<br />

California for the most part are a result<br />

of recreational activities, where people<br />

<strong>and</strong> animals go out into wooded areas.”<br />

There is a seasonality to tick infestations<br />

in the West, she adds, <strong>and</strong> different<br />

ticks spread different diseases. For<br />

instance, Ixodes pacificus, instead of I.<br />

scapularis, is the tick that transmits Lyme<br />

disease in California. That tick primarily<br />

feeds on lizards, instead of deer, <strong>and</strong><br />

lizards have a natural substance in their<br />

bloodstreamthat kills Borrelia organisms.<br />

“As a result, our adult tick populations<br />

are infected at a much lower prevalence<br />

with Borrelia than is seen in the eastern<br />

United States,” Kjemtrup says.<br />

Still there are some novel<br />

pathogens being seen, Fritz adds. For<br />

Black-legged <strong>Tick</strong>: Life Cycle<br />

Eggs<br />

Nymph<br />

Nymph<br />

dormant<br />

Adults lay<br />

eggs<br />

SPRING<br />

WINTER<br />

Larvae<br />

Adults<br />

instance, Arizona recently reported an<br />

outbreak of RMSF, which doesn’t normally<br />

occur in that state, <strong>and</strong> it probably<br />

resulted from a different tick<br />

vector, the brown dog tick.<br />

Kjemtrup adds that canine babesiosis<br />

is a problem in California. Three different<br />

species of canine Babesia have<br />

been documented in Californian dogs:<br />

Babesia canis, B. gibsoni, <strong>and</strong> the recently<br />

described B. conradae. Epidemiologists<br />

SUMMER<br />

FALL<br />

Nymph<br />

dormant<br />

The life cycle of the black-legged tick lasts about 2 years.<br />

Adults lay about 5,000 eggs at a time.<br />

Source: CDC<br />

are reporting B. gibsoni in dogs used in<br />

dog fighting, <strong>and</strong> it is related not only to<br />

tick transmission, but also to the exchange<br />

of body fluids during the fights.<br />

“This is something that has been reported<br />

in the literature recently,”<br />

Kjemtrup says, adding that “scary dog<br />

fighting websites have started posting<br />

treatment recommendations” because<br />

the owners are concerned about this<br />

disease.<br />

There are also more reports of Lyme<br />

disease in canines, she added. In fact,<br />

IDEXX Laboratories recently reported<br />

that Lyme disease has been found in<br />

canines in 48 states. However, Fritz says<br />

this doesn’t mean that dogs have a current<br />

infection, but that some dogs were<br />

exposed to B. burgdorferi at some point<br />

<strong>and</strong> developed antibodies. Nevertheless,<br />

these reports suggest<br />

that exposure of<br />

dogs to B. burgdorferi<br />

may be more widespread<br />

than previously<br />

supposed.<br />

“The tick populations<br />

have increased dramatically<br />

<strong>and</strong> moved into<br />

new areas. If there is one<br />

tick out there, it’s not a<br />

big deal. If there are<br />

1,000 ticks out there, it is<br />

a big deal,” Kocan explains.<br />

“The average tick<br />

burden of a moose in<br />

Canada is about 37,000<br />

ticks.”<br />

Most readers think<br />

about ticks in reference<br />

to dogs <strong>and</strong> cats. The average pet<br />

owner might find one or two ticks <strong>and</strong><br />

pick them off, but ticks are a larger<br />

problem in the cattle industry, where a<br />

steer can harbor more than 3,000 ticks<br />

at once. As the ticks feed, they can lead<br />

to weight reduction <strong>and</strong> secondary infections,<br />

she says. Kocan <strong>and</strong> her team<br />

are working on a tick vaccine for A. americanum,<br />

she adds. There is a tick vaccine<br />

for the cattle tick, Boophilus, that is being<br />

May 2007 | Veterinary Forum 55

used in Cuba, which José de la Fuenté<br />

developed. He is now at Oklahoma<br />

State University working with Kocan.<br />

“We are doing a lot of work to find tickprotective<br />

antigens <strong>and</strong> develop tick<br />

vaccines,” she says.<br />

<strong><strong>Tick</strong>s</strong> have few natural predators.<br />

Fire ants destroy them but the cure is<br />

worse than the problem, <strong>and</strong><br />

Guinea hens eat them but<br />

they are not a preferred<br />

food for most other<br />

birds. So, the best defense<br />

is a good offense,<br />

all the experts<br />

say. Recommend yearround<br />

tick protection<br />

where the rodents might move in. You<br />

want to keep your house from being<br />

attractive to a tick host, be that a deer<br />

or a rodent. One of the worst things<br />

that a person can do is put a deer<br />

feeding station in their backyard, but<br />

people do that all the time. There are<br />

enough deer out there, so we don’t<br />

need to be doing that.<br />

“I’m not advocating getting<br />

rid of the deer, but we<br />

need to recognize that<br />

there has been a consequence<br />

to moving<br />

so close to nature.<br />

“If owners underst<strong>and</strong><br />

why this has<br />

Recommend year-round tick protection for<br />

animals <strong>and</strong> humans, <strong>and</strong> advise owners to do<br />

tick checks after walking in wooded areas.<br />

for animals <strong>and</strong> humans, <strong>and</strong> advise owners<br />

to do tick checks before returning<br />

home if they walk or play in wooded areas.<br />

“If you don’t keep up with that, an<br />

engorged female can drop off in your<br />

yard <strong>and</strong> lay 5,000 eggs. You’ll have a big<br />

problem in a short period. <strong>Tick</strong> control is<br />

a major consideration,” Kocan says.<br />

In addition, tell owners to make sure<br />

their home is not attractive to wildlife<br />

<strong>and</strong> ticks. “There are a lot of things you<br />

can do around your house to make sure<br />

ticks don’t become established,” Kocan<br />

says. “You can cut down bushes <strong>and</strong><br />

mow your grass <strong>and</strong> put a gravel area<br />

around your yard, because they won’t<br />

cross that. Use an integrated pest management<br />

approach.”<br />

Dryden adds: “Try things that reduce<br />

animal harborage. You want to<br />

reduce rodent populations. Don’t<br />

keep a wood pile next to your house<br />

happened, then they will be far more<br />

willing to accept the consequences,<br />

which is year-round, lifelong tick control<br />

for their pets.”<br />

vF<br />

For more information:<br />

Comstedt P, Bergström S, Olsen B, et al: Migratory<br />

passerine birds as reservoirs of Lyme<br />

borreliosis in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis [serial<br />

on the Internet]. 2007 Jul [date cited]. Available<br />

from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/<br />

vol12no07/06-0127.htm<br />

Kocan AA, Kocan KM: <strong>Tick</strong>-transmitted protozoan<br />

diseases of wildlife in North America.<br />

Bull Soc Vector Ecol 1991;16(1):94–108.<br />

Raghavan M, Glickman N, Moore G, et al: Prevalence<br />

of <strong>and</strong> risk factors for canine tick infestation<br />

in the United States, 2002–2004.<br />

Vector-<strong>borne</strong> Zoonotic Dis 2007;7:65–75.<br />

Dryden MW, Payne PA: Biology <strong>and</strong> control of<br />

ticks infesting dogs <strong>and</strong> cats in North America.<br />

Vet Ther 2004;5:139–152.<br />

Kjemtrup AM, Wainwright K, Miller M, et al.<br />

Babesia conradae, sp. nov., a small canine Babesia<br />

identified in California. Vet Parasitol 2006;138:<br />

103–111.<br />

56 Veterinary Forum | May 2007