Causes and Prevention of War - Touro Institute for

Causes and Prevention of War - Touro Institute for

Causes and Prevention of War - Touro Institute for

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

In Conjunction with<br />

<strong>Causes</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Prevention</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

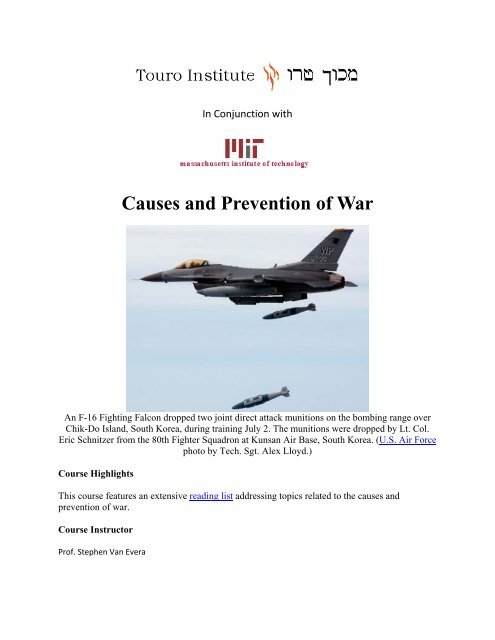

An F-16 Fighting Falcon dropped two joint direct attack munitions on the bombing range over<br />

Chik-Do Isl<strong>and</strong>, South Korea, during training July 2. The munitions were dropped by Lt. Col.<br />

Eric Schnitzer from the 80th Fighter Squadron at Kunsan Air Base, South Korea. (U.S. Air Force<br />

photo by Tech. Sgt. Alex Lloyd.)<br />

Course Highlights<br />

This course features an extensive reading list addressing topics related to the causes <strong>and</strong><br />

prevention <strong>of</strong> war.<br />

Course Instructor<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Stephen Van Evera

Course Description<br />

The causes <strong>and</strong> prevention <strong>of</strong> interstate war are the central topics <strong>of</strong> this course. The course goal<br />

is to discover <strong>and</strong> assess the means to prevent or control war. Hence we focus on manipulable or<br />

controllable war-causes. The topics covered include the dilemmas, misperceptions, crimes <strong>and</strong><br />

blunders that caused wars <strong>of</strong> the past; the origins <strong>of</strong> these <strong>and</strong> other war-causes; the possible<br />

causes <strong>of</strong> wars <strong>of</strong> the future; <strong>and</strong> possible means to prevent such wars, including short-term<br />

policy steps <strong>and</strong> more utopian schemes.<br />

The historical cases covered include World <strong>War</strong> I, World <strong>War</strong> II, Korea, Indochina, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Peloponnesian, Crimean <strong>and</strong> Seven Years wars.<br />

Syllabus<br />

Course Topic<br />

The causes <strong>and</strong> prevention <strong>of</strong> interstate war.<br />

Course Goal<br />

Discovering <strong>and</strong> assessing means to prevent or control war. Hence we focus on manipulable or<br />

controllable causes. The topics covered include the dilemmas, misperceptions, crimes <strong>and</strong><br />

blunders that caused wars <strong>of</strong> the past; the origins <strong>of</strong> these <strong>and</strong> other war-causes; the possible<br />

causes <strong>of</strong> wars <strong>of</strong> the future; <strong>and</strong> possible means to prevent such wars, including short-term<br />

policy steps <strong>and</strong> more utopian schemes.<br />

The historical cases covered include the Peloponnesian <strong>and</strong> Seven Years wars, World <strong>War</strong> I,<br />

World <strong>War</strong> II, Korea, the Arab-Israel conflict, <strong>and</strong> the U.S.-Iraq <strong>and</strong> U.S.-Al Qaeda wars.<br />

Final Exam<br />

A final will be given when all lecture material has been covered <strong>and</strong> the student feels they are<br />

ready.<br />

Readings<br />

Students should buy these books or make sure they are available in a nearby library:<br />

Haffner, Sebastian. The Meaning <strong>of</strong> Hitler. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.<br />

ISBN: 0297775723.<br />

Ienaga, Saburo. The Pacific <strong>War</strong>, 1931-1945. New York, NY: Pantheon, 1979. ISBN:<br />

0394734963.

Iklé, Fred. Every <strong>War</strong> Must End. Revised ed. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1991.<br />

ISBN: 0231076894.<br />

Thucydides. History <strong>of</strong> the Peloponnesian <strong>War</strong>. Translated by Rex <strong>War</strong>ner. Baltimore, MD:<br />

Penguin, 1972. ISBN: 0140440399.<br />

Miller, Steven E., Sean M. Lynn-Jones, <strong>and</strong> Stephen Van Evera. Military Strategy <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Origins <strong>of</strong> the First World <strong>War</strong>. Revised ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.<br />

ISBN: 0691023492.<br />

Stoessinger, John. Nations at Dawn. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1994. ISBN:<br />

0070616264.<br />

Lynn-Jones, Sean M., <strong>and</strong> Steven E. Miller, eds. The Cold <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> After: Prospects <strong>for</strong> Peace.<br />

Exp<strong>and</strong>ed ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993. ISBN: 026262088X.<br />

Rees, Martin. Our Final Hour: A Scientist's <strong>War</strong>ning: How Terror, Error, <strong>and</strong> Environmental<br />

Disaster Threaten Humankind's Future in this Century - On Earth <strong>and</strong> Beyond. New York, NY:<br />

Basic Books, 2003. ISBN: 0465068626.<br />

Calendar<br />

Lec #<br />

I. Introduction<br />

Course calendar<br />

topics<br />

The causes <strong>of</strong> war in perspective. Does international politics follow regular laws <strong>of</strong><br />

1 motion? If so, how can we discover them? Can we use methods like those <strong>of</strong> the physical<br />

sciences?<br />

II. Hypotheses on the <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

2-3 8 Hypotheses on Military Factors as <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Misperception <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong>; Religion <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

4-7<br />

8-9<br />

10 Hypotheses on Misperception <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Hypotheses from Psychology; Militarism; Nationalism; Spirals <strong>and</strong> Deterrence; Religion<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong>; Defects in Academe <strong>and</strong> the Press<br />

14 More <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> Peace: Culture, Gender, Language, Democracy, Social<br />

Equality <strong>and</strong> Social Justice, Minority Rights <strong>and</strong> Human Rights, Prosperity, Economic<br />

Interdependence, Revolution, Capitalism, Imperial Decline <strong>and</strong> Collapse, Cultural<br />

Learning, Emotional Factors (Revenge, Contempt, Honor), Polarity <strong>of</strong> the International<br />

System<br />

<strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> Civil <strong>War</strong>

Course calendar<br />

Lec #<br />

topics<br />

III. Cases: <strong>War</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Crises<br />

10 The Seven Years <strong>War</strong><br />

11 The <strong>War</strong>s <strong>of</strong> German Unification: 1864, 1866, <strong>and</strong> 1870; <strong>and</strong> Segue to World <strong>War</strong> I<br />

12-<br />

14<br />

World <strong>War</strong> I<br />

15<br />

Interlude: Hypotheses on Escalation <strong>and</strong> Limitation <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>; <strong>and</strong> Nuclear Weapons,<br />

Nuclear Strategy, other Weapons <strong>of</strong> Mass Destruction <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

16-<br />

19<br />

World <strong>War</strong> II<br />

20-<br />

21<br />

The Cold <strong>War</strong>, Korea <strong>and</strong> Indochina<br />

22 The Peloponnesian <strong>War</strong><br />

23-<br />

24<br />

The Israel-Arab Conflict; the 2003 U.S.-Iraq <strong>War</strong><br />

IV. The Future <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

25-<br />

26<br />

Testing <strong>and</strong> Applying Theories <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> Causation; the Future <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>, Solutions to <strong>War</strong><br />

Final Exam<br />

Readings<br />

The readings are also available by session. This course also has an extensive set <strong>of</strong> further<br />

readings.<br />

Text<br />

Haffner, Sebastian. The Meaning <strong>of</strong> Hitler. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.<br />

ISBN: 0297775723.<br />

Ienaga, Saburo. The Pacific <strong>War</strong>, 1931-1945. New York, NY: Pantheon, 1979. ISBN:<br />

0394734963.<br />

Iklé, Fred. Every <strong>War</strong> Must End. Revised ed. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1991.<br />

ISBN: 0231076894.<br />

Thucydides. History <strong>of</strong> the Peloponnesian <strong>War</strong>. Translated by Rex <strong>War</strong>ner. Baltimore, MD:<br />

Penguin, 1972. ISBN: 0140440399.

Miller, Steven E., Sean M. Lynn-Jones, <strong>and</strong> Stephen Van Evera. Military Strategy <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Origins <strong>of</strong> the First World <strong>War</strong>. Revised ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.<br />

ISBN: 0691023492.<br />

Stoessinger, John. Nations at Dawn. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1994. ISBN:<br />

0070616264.<br />

Lynn-Jones, Sean M., <strong>and</strong> Steven E. Miller, eds. The Cold <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> After: Prospects <strong>for</strong> Peace.<br />

Exp<strong>and</strong>ed ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993. ISBN: 026262088X.<br />

Rees, Martin. Our Final Hour: A Scientist's <strong>War</strong>ning: How Terror, Error, <strong>and</strong> Environmental<br />

Disaster Threaten Humankind's Future in this Century - On Earth <strong>and</strong> Beyond. New York, NY:<br />

Basic Books, 2003. ISBN: 0465068626.<br />

I also recommend--but don't require--that students buy a copy <strong>of</strong> the following book that will<br />

improve your papers:<br />

Turabian, Kate L. A Manual <strong>for</strong> Writers <strong>of</strong> Term Papers, Theses, <strong>and</strong> Dissertations. 6th ed. Rev.<br />

by John Grossman <strong>and</strong> Alice Bennett. Chicago, IL: University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN:<br />

0226816273.<br />

Turabian has the basic rules <strong>for</strong> <strong>for</strong>matting footnotes <strong>and</strong> other style rules. You will want to<br />

follow these rules so your writing looks spiffy <strong>and</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional.<br />

Readings by Session<br />

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

I. Introduction<br />

1<br />

The causes <strong>of</strong> war in perspective. Does<br />

international politics follow regular laws <strong>of</strong><br />

motion? If so, how can we discover them? Can<br />

we use methods like those <strong>of</strong> the physical<br />

sciences?<br />

II. Hypotheses on the <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

2‐3<br />

8 Hypotheses on Military Factors as <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>War</strong><br />

Ziegler, David. "Disarmament." Chapter 15 in<br />

<strong>War</strong>, Peace <strong>and</strong> International Politics. 2nd ed.<br />

Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1981, pp. 249‐267.<br />

ISBN: 0316984930.

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

A basic discussion <strong>of</strong> a modest proposal: tossing<br />

the weapons in the ocean. A good idea?<br />

Schelling, Thomas C. "The Dynamics <strong>of</strong> Mutual<br />

Alarm." In Arms <strong>and</strong> Influence. New Haven, CT:<br />

Yale, 1966, pp. 221‐251.<br />

The classic statement <strong>of</strong> "stability theory," which<br />

frames the dangers that arise with a first‐strike<br />

advantage.<br />

Blainey, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey. "Dreams <strong>and</strong> Delusions <strong>of</strong> a<br />

Coming <strong>War</strong>." Chapter 3 in The <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>.<br />

3rd ed. New York, NY: Free Press, 1988, pp. 35‐<br />

56. ISBN: 0029035910<br />

False optimism as a cause <strong>of</strong> war.<br />

Van Evera, Stephen. "Primed <strong>for</strong> Peace: Europe<br />

After the Cold <strong>War</strong>." In Cold <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> After:<br />

Prospects <strong>for</strong> Peace. Edited by Sean M. Lynn<br />

Jones <strong>and</strong> Steven E. Miller. Cambridge, MA: MIT<br />

Press, 1993, pp. 193‐203. ISBN: 026262088X.<br />

Note: these page are 20% <strong>of</strong> the article; much <strong>of</strong><br />

the rest (pp. 204‐236) is assigned over the next<br />

two weeks. Please focus <strong>for</strong> now on pages 193‐<br />

203, which discuss the crucial matter <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fense,<br />

defense, <strong>and</strong> war.<br />

I include this article partly to clue you to my<br />

reflexes on the causes <strong>of</strong> war. Your skepticism is<br />

allowed.<br />

For your optional delectation see also John<br />

Mueller's collection <strong>of</strong> predictions about war,<br />

"Various Shapes <strong>of</strong> Things to Come". Has our<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> war made progress since the<br />

days <strong>of</strong> Henry Buckle, R<strong>and</strong>olph Bourne, <strong>and</strong><br />

David Starr Jordan? And see also, <strong>for</strong><br />

background, the data on war deaths from:

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

Sivard, Ruth. World Military <strong>and</strong> Social<br />

Expenditures 1987‐88. Washington, DC: World<br />

Priorities, 28‐31.<br />

Jervis, Robert. "Hypotheses on Misperception."<br />

In International Politics: Anarchy, Force, Political<br />

Economy, <strong>and</strong> Decision Making. 2nd ed. Edited<br />

by Robert J. Art <strong>and</strong> Robert Jervis. Boston, MA:<br />

Little, Brown <strong>and</strong> Co, 1985, pp. 510‐526. ISBN:<br />

0316052396.<br />

A classic discussion <strong>of</strong> the delusions to which<br />

states are prone. Is Jervis' list <strong>of</strong> myopias a good<br />

one? Do they arise from the psychological<br />

sources he stresses, or are other causes at work?<br />

4‐7<br />

Misperception <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong>; Religion <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

10 Hypotheses on Misperception <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Causes</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Hypotheses from Psychology; Militarism;<br />

Nationalism; Spirals <strong>and</strong> Deterrence; Religion<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong>; Defects in Academe <strong>and</strong> the Press<br />

———. Perception <strong>and</strong> Misperception in<br />

International Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton<br />

University Press, 1976, pp. 58‐84. ISBN:<br />

0691100497.<br />

Some say conflict is best resolved by the carrot,<br />

while using the stick merely provokes; others<br />

would use the stick, warning that using the<br />

carrot ("appeasement") emboldens others to<br />

make more dem<strong>and</strong>s. Who's right? Probably<br />

both ‐ but under what circumstances? <strong>and</strong> how<br />

can you tell which circumstances you are in?<br />

Van Evera, Stephen. "Primed <strong>for</strong> Peace." pp. 204‐<br />

211.<br />

Hedges, Chris. "In Bosnia's Schools, 3 Ways<br />

Never to Learn From History," New York Times,<br />

November 25, 1997, p. A1.<br />

It was once said that "war begins in the<br />

classroom." Is that such a silly notion? Do the<br />

Balkans' separate realities, <strong>and</strong> the Balkan wars<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 1990s, stem from separate <strong>and</strong> divergent

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

teaching <strong>of</strong> the past?<br />

Benjamin, Daniel, <strong>and</strong> Steven Simon. The Age <strong>of</strong><br />

Sacred Terror. New York, NY: R<strong>and</strong>om House,<br />

2002, pp. 38‐55, 61‐68, 91‐94, <strong>and</strong> 419‐446.<br />

ISBN: 0375508597.<br />

Pages 38‐55, 62‐68, 91‐94 describe the Islamist<br />

currents <strong>of</strong> thinking that spawned Osama Bin<br />

Laden's Al Qaeda. Al Qaeda's violence stems<br />

from a stream <strong>of</strong> Islamist thought going back to<br />

ibn Taymiyya, a bellicose Islamic thinker from the<br />

13th century; to Abd al‐Wahhab (1703‐1792),<br />

the harsh <strong>and</strong> rigid shaper <strong>of</strong> modern Saudi<br />

Arabian Islam; to Rashid Rida (1866‐1935) <strong>and</strong><br />

Hassan al‐Banna (?‐1949); <strong>and</strong> above all to<br />

Sayyid Qutb (?‐1966), the shaper <strong>of</strong> modern<br />

Islamism. Taymiyya, al‐Wahhab <strong>and</strong> Qutb are<br />

covered here. Covered also (pp. 91‐94) is the<br />

frightening rise <strong>of</strong> apocalyptic thinking in the<br />

Islamic world. What causes the murderous<br />

thinking described here?<br />

Pages 419‐446 cover the phenomenon <strong>of</strong><br />

millenarianism (apocalyptic thinking) in other<br />

religions‐‐Judaism, Buddhism, <strong>and</strong> Christianity.<br />

This violent, even genocidal (globacidal?) <strong>for</strong>m <strong>of</strong><br />

religious thought has appeared widely in the last<br />

two decades. Why? How can it be tamed be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

it is used to justify great horrors?<br />

Mishra, Pankaj. "The Other Face <strong>of</strong> Fanaticism,"<br />

New York Times, February 2, 2003, Late edition.<br />

The Hindu extremist movement <strong>of</strong> India is<br />

painted here, lest anyone think the Muslim<br />

world has a corner on murderous religious<br />

fanaticism.<br />

Lampman, Jane. "Mixing Prophecy <strong>and</strong> Politics,"

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

Christian Science Monitor, July 7, 2004.<br />

Christians <strong>of</strong> the premillennial dispensationalist<br />

perspective oppose an Israel‐Palestinian peace<br />

settlement. Their larger objective: destroying the<br />

world.<br />

Morgenthau, Hans J. "The Purpose <strong>of</strong> Political<br />

Science." In A Design <strong>for</strong> Political Science: Scope,<br />

Objectives, <strong>and</strong> Methods. Edited by James C.<br />

Charlesworth. Philadelphia, PA: American<br />

Academy <strong>of</strong> Political <strong>and</strong> Social Science, 1966,<br />

pp. 69‐74. ISBN: 0836917898.<br />

Are scholars part <strong>of</strong> the solution or part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

problem? An eminent pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> international<br />

relations says his colleagues are gutless wonders<br />

who won't tell the state or society when they are<br />

wrong.<br />

Pearson, David. "The Media <strong>and</strong> Government<br />

Deception." Propag<strong>and</strong>a Review (Spring 1989):<br />

6‐11.<br />

Pearson thinks the American press is obedient to<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficial views, <strong>and</strong> afraid to criticize. Antiestablishment<br />

paranoia or the real picture?<br />

8‐9<br />

14 More <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> Peace: Culture,<br />

Gender, Language, Democracy, Social Equality<br />

<strong>and</strong> Social Justice, Minority Rights <strong>and</strong> Human<br />

Rights, Prosperity, Economic Interdependence,<br />

Revolution, Capitalism, Imperial Decline <strong>and</strong><br />

Collapse, Cultural Learning, Emotional Factors<br />

(Revenge, Contempt, Honor), Polarity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

International System<br />

<strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> Civil <strong>War</strong><br />

Bellak, Leopold. "Why I Fear the Germans," (oped)<br />

New York Times, April 4, 1990, p. A29; <strong>and</strong><br />

"Responses," New York Times, May 10, 1990, p.<br />

A30.<br />

Germany has a flawed national character. Fair? If<br />

not, what explains past German conduct? If true,<br />

is this satisfying?<br />

Harris, Louis. "The Gender Gulf," New York<br />

Times, December 7, 1990, p. A35.<br />

The problem is: men? (Women are more dovish.)<br />

Goldstein, Joshua S. "Feminism." In International

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

Relations. New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1994,<br />

pp. 282‐295. ISBN: 0065018648.<br />

A good basic summary <strong>of</strong> feminist arguments on<br />

the causes <strong>of</strong> war.<br />

Mearsheimer, John. "Back to the Future:<br />

Instability in Europe After the Cold <strong>War</strong>." In Cold<br />

<strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> After. Edited by Sean M. Lynn‐Jones<br />

<strong>and</strong> Steven E. Miller. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press,<br />

1993, pp. 147‐155, 165‐167, <strong>and</strong> 176‐187. ISBN:<br />

026262088X.<br />

Five theories <strong>of</strong> war‐causation are discussed<br />

there. Note: you might skim the rest <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Mearsheimer article as well, to get his whole<br />

drift.<br />

Van Evera. "Primed <strong>for</strong> Peace." pp. 211‐236.<br />

On the democracy <strong>and</strong> polarity questions, who is<br />

more persuasive, Mearsheimer or this guy?<br />

Eriksson, Mikael, <strong>and</strong> Peter Wallensteen. "Armed<br />

Conflict 1989‐2003." Journal <strong>of</strong> Peace Research<br />

41, no. 5 (September 2004): 625‐631.<br />

Nearly all wars today are civil wars. The number<br />

<strong>of</strong> wars has declined sharply since 1990 ‐ back<br />

down to the number observed in the mid‐1970s,<br />

but still more than the number observed during<br />

1946‐76. Will these trends continue?<br />

III. Cases: <strong>War</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Crises<br />

Brown, Michael E., ed. "Introduction." In The<br />

International Dimensions <strong>of</strong> Internal Conflict.<br />

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996, pp. 1‐31. ISBN:<br />

0262522098.<br />

A survey <strong>of</strong> hypotheses on the causes <strong>of</strong> internal<br />

conflict.

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

Palmer, R. R., <strong>and</strong> Joel Colton. "The Great <strong>War</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

the Mid‐Eighteenth Century." In A History <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Modern World. 7th ed. New York, NY: Knopf,<br />

1991, pp. 273‐285. ISBN: 0679410147.<br />

This is a st<strong>and</strong>ard textbook summary <strong>of</strong> events.<br />

Please focus on pp. 278‐281, dealing with the<br />

outbreak <strong>of</strong> the Franco‐British war.<br />

10 The Seven Years <strong>War</strong><br />

Smoke, Richard. "The Seven Years <strong>War</strong>." In <strong>War</strong>:<br />

Controlling Escalation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard<br />

University Press, 1977, pp. 195‐236. ISBN:<br />

0674945956.<br />

Smoke's chapter is a good historical synopses <strong>of</strong><br />

this war. What general theories <strong>of</strong> war causes<br />

does his account support? How might this war<br />

have been prevented? By whom?<br />

11<br />

The <strong>War</strong>s <strong>of</strong> German Unification: 1864, 1866,<br />

<strong>and</strong> 1870; <strong>and</strong> Segue to World <strong>War</strong> I<br />

Ziegler, David. "The <strong>War</strong>s <strong>for</strong> German<br />

Unification." Chapter 1 in <strong>War</strong>, Peace <strong>and</strong> IR. 2nd<br />

ed. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1981, pp. 7‐20.<br />

ISBN: 0316984930.<br />

A (very) basic history.<br />

12‐<br />

14<br />

World <strong>War</strong> I<br />

Palmer, R.R. <strong>and</strong> Colton, Joel. "The First World<br />

<strong>War</strong>." In History <strong>of</strong> the Modern World. 7th ed.<br />

New York, NY: Knopf, 1991, pp. 695‐718. ISBN:<br />

0679410147.<br />

This is assigned to provide basic background <strong>for</strong><br />

non‐aficionados <strong>of</strong> WWI.<br />

Geiss, Imanuel. German Foreign Policy, 1871‐<br />

1914. Boston, MA: Routledge & Kegan Paul,<br />

1976, pp. vii‐ix, 75‐83, 106‐181, <strong>and</strong> 206‐207.<br />

ISBN: 0710083033.<br />

The key pages are pp. 121‐127, 142‐150, <strong>and</strong><br />

206‐207 ‐ focus on these pages <strong>and</strong> read the rest<br />

more lightly. (Make sure not to miss the tale <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>War</strong> Council <strong>of</strong> 8 December 1912, including

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

Admiral Müller's notes on the Council.) This book<br />

summarizes the views <strong>of</strong> the "Fischer School,"<br />

which argues that German aggression was a<br />

prime cause <strong>of</strong> World <strong>War</strong> I. Others believe<br />

Fisher <strong>and</strong> Geiss blame Germany unduly. Who's<br />

right?<br />

Strachan, Hew. The First World <strong>War</strong>. Vol. 1, To<br />

Arms. Ox<strong>for</strong>d, UK: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 2001,<br />

pp. 51 (bottom)‐55 (bottom). ISBN: 0198208774.<br />

Strachan, an anti‐Fischerite, thinks that the<br />

December 8 1912 <strong>War</strong> Council was no war<br />

council at all, but rather an indecisive bull<br />

session <strong>of</strong> sorts. Are his reasons persuasive?<br />

Miller, ed. Military Strategy <strong>and</strong> the Origins <strong>of</strong><br />

the First World <strong>War</strong>. pp. xi‐xix, 20‐108.<br />

A Europe‐wide "Cult <strong>of</strong> the Offensive" caused the<br />

war; the militaries <strong>of</strong> Europe were responsible.<br />

Kitchen, Martin. "The Army <strong>and</strong> the Idea <strong>of</strong><br />

Preventive <strong>War</strong>," <strong>and</strong> "The Army <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Civilians." Chapters 5 <strong>and</strong> 6 in The German<br />

Officer Corps, 1890‐1914. Ox<strong>for</strong>d, UK: Clarendon,<br />

1968, pp. 96‐142. ISBN: 0198214677.<br />

In Germany the army also purveyed the concept<br />

<strong>of</strong> preventive war, the notion that war was<br />

healthy <strong>and</strong> beneficial, <strong>and</strong> other exotic ideas;<br />

<strong>and</strong> within Germany it became a law unto itself ‐<br />

a "state within the state," in Gordon Craig's<br />

phrase.<br />

Langsam, Walter Consuelo. "Nationalism <strong>and</strong><br />

History in the Prussian Elementary Schools<br />

Under William II." In Nationalism <strong>and</strong><br />

Internationalism: essays inscribed to Carlton J. H.<br />

Hayes. Edited by Edward Mead Earle. New York,<br />

NY: Columbia University Press 1950, pp. 241‐260.

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

German elementary <strong>and</strong> high schools were<br />

channels <strong>of</strong> nationalist propag<strong>and</strong>a.<br />

Joll, James. Origins <strong>of</strong> the First World <strong>War</strong>. 2nd<br />

ed. New York, NY: Longman, 1992, chapter 2, pp.<br />

9‐34. ISBN: 0582089204.<br />

A summary <strong>of</strong> the events <strong>of</strong> the strange <strong>and</strong><br />

amazing July crisis.<br />

For more on World <strong>War</strong> I origins see the World<br />

<strong>War</strong> I Document Archive.<br />

And <strong>for</strong> more on the role <strong>of</strong> German public<br />

opinion in causing the war see specifically:<br />

Mommsen, Wolfgang J. "Nationalism,<br />

Imperialism <strong>and</strong> Official Press Policy in<br />

Wilhelmine Germany 1850‐1914." In Collection<br />

de l'Ecole Francaise de Rome, Opinion Publique<br />

et Politique Exterieure I 1870‐1915. Milano:<br />

Universita de Milano/Ecole Francaise de Rome,<br />

1981, pp. 367‐383. ISBN: 2728300321.<br />

Iklé, Fred. Every <strong>War</strong> Must End. pp. 1‐105.<br />

Can war be rationally conducted <strong>and</strong> controlled?<br />

This superb book makes you wonder.<br />

15<br />

Interlude: Hypotheses on Escalation <strong>and</strong><br />

Limitation <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>; <strong>and</strong> Nuclear Weapons,<br />

Nuclear Strategy, other Weapons <strong>of</strong> Mass<br />

Destruction <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Ziegler, David. "The Balance <strong>of</strong> Terror." In <strong>War</strong>,<br />

Peace <strong>and</strong> International Politics. 2nd ed. Boston,<br />

MA: Little, Brown, 1981, pp. 221‐234. ISBN:<br />

0316984930.<br />

A basic rundown <strong>of</strong> the issues.<br />

Rees, Martin. Our Final Hour: A Scientist's<br />

<strong>War</strong>ning: How Terror, Error, <strong>and</strong> Environmental<br />

Disaster Threaten Humankind's Future in this<br />

Century ‐ On Earth <strong>and</strong> Beyond. New York, NY:<br />

Basic Books, 2003, pp. 1‐24, 41‐60, <strong>and</strong> 73‐88.

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

ISBN: 0465068626.<br />

The advance <strong>of</strong> science has a fearsome<br />

byproduct: we are discovering ever more<br />

powerful means <strong>of</strong> destruction. These<br />

destructive powers are being democratized: the<br />

mayhem that only major states can do today<br />

may lie within the capacity <strong>of</strong> millions <strong>of</strong><br />

individuals in the future unless we somehow<br />

change course. Deterrence works against states<br />

but will fail against crazed non‐state<br />

organizations or individuals. How can the spread<br />

<strong>of</strong> destructive powers be controlled?<br />

For more on controlling the longterm<br />

bioweapons danger see "Controlling Dangerous<br />

Pathogens: A Prototype Protective Oversight<br />

System." (a monograph by John Steinbruner <strong>and</strong><br />

Elisa Harris.)<br />

Kelly, Henry C. "Terrorism <strong>and</strong> the Biology Lab,"<br />

New York Times, July 2, 2003.<br />

The biology pr<strong>of</strong>ession must realize that its<br />

research, if left unregulated, could produce<br />

discoveries that gravely threaten our safety.<br />

Biologists must develop a strategy to keep<br />

biology from being used <strong>for</strong> destructive ends.<br />

For more on controlling the longterm<br />

bioweapons danger see "Controlling Dangerous<br />

Pathogens: A Prototype Protective Oversight<br />

System." (a monograph by John Steinbruner <strong>and</strong><br />

Elisa Harris.)<br />

16‐<br />

19<br />

World <strong>War</strong> II<br />

Palmer, R. R., <strong>and</strong> Joel Colton. A History <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Modern World. 7th ed. New York, NY: Knopf,<br />

1991, pp. 798‐799 <strong>and</strong> 822‐849. ISBN:<br />

0679410147.<br />

This is a basic st<strong>and</strong>ard history <strong>of</strong> the events

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

leading up to the war.<br />

Haffner, Sebastian. The Meaning <strong>of</strong> Hitler. pp. 3‐<br />

165.<br />

Herwig, Holger. "Clio Deceived: Patriotic Self‐<br />

Censorship in Germany After the Great <strong>War</strong>." In<br />

Military Strategy <strong>and</strong> the Origins <strong>of</strong> the First<br />

World <strong>War</strong>. Edited by Miller. Princeton, NJ:<br />

Princeton University Press, pp. 262‐301. ISBN:<br />

0691022321.<br />

How Germans mis‐remembered the origins <strong>and</strong><br />

aftermath <strong>of</strong> the First World <strong>War</strong>.<br />

Wette, Wolfram. "From Kellog to Hitler (1928‐<br />

1933). German Public Opinion Concerning the<br />

Rejection or Glorification <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>." In The German<br />

Military in the Age <strong>of</strong> Total <strong>War</strong>. Edited by<br />

Wilhelm Deist. Dover, NH: Berg, 1985, pp. 71‐99.<br />

ISBN: 0907582141.<br />

How Germans came to love war again so soon<br />

after the Marne <strong>and</strong> Verdun. What explains the<br />

bizarre developments Wette describes?<br />

Sagan, Scott. "The Origins <strong>of</strong> the Pacific <strong>War</strong>." In<br />

The Origins <strong>and</strong> <strong>Prevention</strong> <strong>of</strong> Major <strong>War</strong>s.<br />

Edited by Robert I. Rotberg <strong>and</strong> Theodore K.<br />

Rabb. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press,<br />

1988, pp. 323‐352. ISBN: 0521379555.<br />

Ienaga. The Pacific <strong>War</strong> 1931‐1945. pp. vii‐152,<br />

247‐256.<br />

Was the Japanese decision <strong>for</strong> war a rational<br />

response to circumstances, or in some sense<br />

"irrational"? Ienaga <strong>and</strong> Sagan disagree ‐ who's<br />

right?<br />

Utley, Jonathan G. Going to <strong>War</strong> With Japan

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

1937‐1941. Knoxville, TN: University <strong>of</strong><br />

Tennessee Press, 1985, pp. 151‐156. ISBN:<br />

0870494457.<br />

Heinrichs, Waldo. The Threshold <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>: Franklin<br />

D. Roosevelt <strong>and</strong> American Entry into World <strong>War</strong><br />

II. New York, NY: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1988,<br />

pp. 141‐142, 177, <strong>and</strong> 246‐247 (note 68). ISBN:<br />

0195061683.<br />

Was the crucial American decision to cut <strong>of</strong>f oil<br />

exports to Japan taken by a bureaucracy out <strong>of</strong><br />

control? Utley <strong>and</strong> Heinrichs disagree. How can<br />

this mystery be unravelled?<br />

Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. "Letter to the Editor."<br />

New York Review <strong>of</strong> Books. February 6, 1997, p.<br />

40.<br />

A summary <strong>of</strong> Goldhagen's famous argument<br />

that Germany committed the holocaust because<br />

most Germans embraced an eliminationist antisemitism.<br />

How could we test Goldhagen's<br />

argument?<br />

Krist<strong>of</strong>f, Nicholas. "A Tojo Battles History, <strong>for</strong><br />

Gr<strong>and</strong>pa <strong>and</strong> <strong>for</strong> Japan," New York Times, April<br />

22, 1999.<br />

Mythmaking about Japan's role in World <strong>War</strong> II<br />

continues, stirring suspicion <strong>and</strong> anger<br />

elsewhere in Asia.<br />

20‐<br />

21<br />

The Cold <strong>War</strong>, Korea <strong>and</strong> Indochina<br />

Paterson, Thomas G., J. Gary Clif<strong>for</strong>d, <strong>and</strong><br />

Kenneth Hagan. American Foreign Policy: A<br />

History Since 1900. Lexington, VA: D.C. Heath,<br />

1983, pp. 471‐480, 519‐539, <strong>and</strong> 546‐563. ISBN:<br />

0669045675.<br />

Stoessinger, John. Nations at Dawn. pp. xi‐119.<br />

Paterson, et al. is a st<strong>and</strong>ard history; Stoessinger

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

is interpretive.<br />

22 The Peloponnesian <strong>War</strong><br />

Thucydides. The Peloponnesian <strong>War</strong>. pp. 35‐108,<br />

118‐164, 212‐223, 400‐429, 483‐488, <strong>and</strong> 516‐<br />

538.<br />

A famous history by a great strategist that many<br />

later readers, across many centuries, felt evoked<br />

their own times <strong>and</strong> tragedies.<br />

Humphreys, R. Stephen. "The Arab Israeli<br />

Conflict." Between Memory <strong>and</strong> Desire: The<br />

Middle East in a Troubled Age. Berkeley, CA:<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Cali<strong>for</strong>nia Press, 1999, pp. 46‐59.<br />

ISBN: 0520214110.<br />

Arabs <strong>and</strong> Israelis both see themselves as<br />

victims, with tragic results.<br />

23‐<br />

24<br />

The Israel‐Arab Conflict; the 2003 U.S.‐Iraq <strong>War</strong><br />

Shlaim, Avi. "The Middle East: Origins <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Arab‐Israeli <strong>War</strong>s." In Explaining International<br />

Relations Since 1945. Edited by Ngaire Woods.<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, UK: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1996, pp.<br />

219‐236. ISBN: 0198741960.<br />

(skim 219‐221, read 221‐236.) Highlights <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Arab‐Israeli wars <strong>of</strong> 1948, 1967, 1969‐70, 1973,<br />

<strong>and</strong> 1982 <strong>and</strong> the Persian Gulf <strong>War</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1991 are<br />

outlined here.<br />

Van Evera, Stephen. "Memory <strong>and</strong> the Israel‐<br />

Palestinian Conflict: Time <strong>for</strong> New Narratives."<br />

Faculty Working Paper, Massachusetts <strong>Institute</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> Technology, 2003.<br />

Arabs <strong>and</strong> Israelis both see themselves as<br />

victims, <strong>and</strong> they are. But they see themselves as<br />

victims <strong>of</strong> each other, while their real victimizer<br />

is the Christian West. If they knew this they<br />

could better end their conflict.<br />

Shavit, Ari. "Survival <strong>of</strong> the Fittest," Ha'aretz,

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

January 14, 2004.<br />

Shavit interviews Benny Morris, one <strong>of</strong> Israel's<br />

leading historians, on the realities <strong>and</strong> ethics <strong>of</strong><br />

Israel's expulsion <strong>of</strong> 700,000‐750,000<br />

Palestinians during the 1948 war. In the past<br />

Morris led in exposing the expulsion; now he is a<br />

prominent defender <strong>of</strong> it, arguing that<br />

sometimes ethnic cleansing is necessary.<br />

Bumiller, Elisabeth. "Was a Tyrant Prefigured by<br />

Baby Saddam?" New York Times, May 15, 2004.<br />

Saddam Hussein was severely abused as a child<br />

<strong>and</strong> as a result suffered narcissism <strong>and</strong> other<br />

personality disorders. Does this help explain the<br />

1991 <strong>and</strong> 2003 Iraq wars? Can the U.S. deter or<br />

coerce such people if it better underst<strong>and</strong>s their<br />

personal demons?<br />

IV. The Future <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Stoessinger, John G. Why Nations Go To <strong>War</strong>. 9th<br />

ed. Belmont, CA: Thompson Wadsworth, 2004,<br />

pp. 273‐308. ISBN: 0534631479.<br />

An account <strong>of</strong> the 2003 U.S.‐Iraq war.<br />

Kaysen, Carl. "Is <strong>War</strong> Obsolete?" In Cold <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

After. Edited by Sean M. Lynn‐Jones. pp. 81‐103.<br />

Kaysen says past causes <strong>of</strong> war are already gone.<br />

But if he's right, why does war continue?<br />

25‐<br />

26<br />

Testing <strong>and</strong> Applying Theories <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> Causation;<br />

the Future <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>, Solutions to <strong>War</strong><br />

Ziegler, David. "World Government," <strong>and</strong><br />

"Collective Security." Chapters 8, <strong>and</strong> 11 in <strong>War</strong>,<br />

Peace <strong>and</strong> IR. pp. 127‐45, 179‐203. ISBN:<br />

0316984930.<br />

Many people have <strong>of</strong>fered these answers. Do<br />

you think they would work? (Why haven't they<br />

been implemented yet?)

Course readings.<br />

Lec # topics readings<br />

Nitze, Paul. "A Threat Mostly to Ourselves," New<br />

York Times, October 28, 1999, p. A25.<br />

A call <strong>for</strong> nuclear disarmament from a prominent<br />

Cold <strong>War</strong> hawk. (In 1950 Nitze wrote NSC‐68, the<br />

guiding plan <strong>for</strong> America's great Cold <strong>War</strong><br />

military buildup.)<br />

Huntington, Samuel P. The Clash <strong>of</strong> Civilizations<br />

<strong>and</strong> the Remaking <strong>of</strong> World Order. New York, NY:<br />

Simon <strong>and</strong> Schuster, 1996, pp. 209‐218 <strong>and</strong> 254‐<br />

266. ISBN: 0684811642.<br />

("Islam <strong>and</strong> the West," <strong>and</strong> "Islam's Bloody<br />

Borders.")<br />

Review again Benjamin <strong>and</strong> Simon. Age <strong>of</strong> Sacred<br />

Terror. New York, NY: R<strong>and</strong>om House, 2002, 38‐<br />

55, 61‐68, 91‐94, <strong>and</strong> 419‐446. ISBN:<br />

0375508597.<br />

Review again Rees, Our Final Hour, pp. 41‐60,<br />

<strong>and</strong> 73‐88 (assigned above.)<br />

Final Exam<br />

Bush, George W. "Second Inaugural Address."<br />

Inauguration, Washington, DC, January 20, 2005.<br />

President Bush announces a U.S. policy <strong>of</strong><br />

promoting freedom <strong>and</strong> liberty, on grounds that<br />

"as long as whole regions <strong>of</strong> the world simmer in<br />

resentment <strong>and</strong> tyranny... violence will gather<br />

<strong>and</strong> multiply in destructive power, <strong>and</strong> cross the<br />

most defended borders, <strong>and</strong> raise a mortal<br />

threat.... The survival <strong>of</strong> liberty in our l<strong>and</strong><br />

increasingly depends on the success <strong>of</strong> liberty in<br />

other l<strong>and</strong>s. The best hope <strong>for</strong> peace in our<br />

world is the expansion <strong>of</strong> freedom."

Further Readings<br />

The <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

The causes <strong>of</strong> war, general <strong>and</strong> theoretical works:<br />

Blainey, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey. The <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>. New York, NY: Free Press, 1973.<br />

Bramson, Leon, <strong>and</strong> George W. Goethals, eds. <strong>War</strong>: Studies from Psychology, Sociology,<br />

Anthropology. Revised ed. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1968.<br />

Brodie, Bernard. "Some Theories on the <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>." In <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> Politics. New York, NY:<br />

Macmillan, 1973, pp. 276-340.<br />

Cashman, Greg. What <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>War</strong>? An Introduction to Theories <strong>of</strong> International Conflict. New<br />

York, NY: Lexington Books, 1999.<br />

Dougherty, James E., <strong>and</strong> Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr. Contending Theories <strong>of</strong> International<br />

Relations: A Comprehensive Survey. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1990. Parts.<br />

Falk, Richard A., <strong>and</strong> Samuel S. Kim. The <strong>War</strong> System: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Boulder,<br />

CO: Westview, 1980.<br />

Kagan, Donald. On the Origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Preservation <strong>of</strong> Peace. New York, NY:<br />

Doubleday, 1994.<br />

Kurtz, Lester, ed. Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong> Conflict. 3 vols. San Diego, CA:<br />

Academic Press, 1999.<br />

Levy, Jack. "The <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>: A Review <strong>of</strong> Theories." In Behavior, Society, <strong>and</strong> Nuclear<br />

<strong>War</strong>. 2 vols. Edited by Philip E. Tetlock, Jo L. Husb<strong>and</strong>s, Robert Jervis, Paul C. Stern, <strong>and</strong><br />

Charles Tilly. New York, NY: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1989, 1991, pp. 1:209-333. ISBN:<br />

0195057651.<br />

Levy, Jack S. "The <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Conditions <strong>of</strong> Peace." In Annual Review <strong>of</strong> Political<br />

Science. Vol. 1. 1998, pp. 139-165.<br />

Midlarsky, Manus I., ed. H<strong>and</strong>book <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> Studies. Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman, 1989.<br />

Rotberg, Robert I., <strong>and</strong> Theodore K. Rabb, eds. The Origins <strong>and</strong> <strong>Prevention</strong> <strong>of</strong> Major <strong>War</strong>s. New<br />

York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1989.<br />

Waltz, Kenneth N. Man, the State, <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong>. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1954.

Arms <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Borg, Marlies Ter. "Reducing Offensive Capabilities - the Attempt <strong>of</strong> 1932." Journal <strong>of</strong> Peace<br />

Research 29, no. 2 (1992): 145-160.<br />

Jervis, Robert. "Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma." World Politics (January 1978): 167-<br />

214.<br />

Levy, Jack S. "Declining Power <strong>and</strong> the Preventive Motivation <strong>for</strong> <strong>War</strong>." World Politics 40, no.<br />

1 (October 1987): 82-107.<br />

Lynn-Jones, Sean M. "Offense-Defense Theory <strong>and</strong> its Critics." Security Studies 4, no. 4<br />

(Summer 1995): 660-694.<br />

Schelling, Thomas. Arms <strong>and</strong> Influence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1966. Parts.<br />

Schelling, Thomas, <strong>and</strong> Morton Halperin. Strategy <strong>and</strong> Arms Control. New York, NY: Twentieth<br />

Century Fund, 1961. Parts.<br />

Misperception<br />

Janis, Irving L. Victims <strong>of</strong> Groupthink. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1972.<br />

Jervis, Robert. "<strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> Misperception." In The Origins <strong>and</strong> <strong>Prevention</strong> <strong>of</strong> Major <strong>War</strong>s. Edited<br />

by Robert I. Rotberg <strong>and</strong> Theodore K. Rabb. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1989,<br />

pp. 101-126. ISBN: 0521379555.<br />

———. "Hypotheses on Misperception." World Politics 20, no. 3 (April 1968): 454-479. Also<br />

reprinted in Power, Action <strong>and</strong> Interaction. Edited by George H. Quester. Boston, MA: Little,<br />

Brown, 1971, pp. 104-132.<br />

May, Ernest R. "'Lessons' <strong>of</strong> the Past: The Use <strong>and</strong> Misuse <strong>of</strong> History in American Foreign<br />

Policy. New York, NY: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1973.<br />

Wildavsky, Aaron. "The Self-Evaluating Organization." Public Administration Review.<br />

September/October 1972, pp. 509-520.<br />

Gender <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Goldstein, Joshua S. <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> Gender. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001.<br />

ISBN: 0521807166.<br />

Cohn, Carol. "Sex <strong>and</strong> Death in the Rational World <strong>of</strong> Defense Intellectuals." Signs 12, no. 4<br />

(Summer 1987): 687-718. Within <strong>and</strong> Without: Women, Gender, <strong>and</strong> Theory.

Forcey, Linda Rennie. "Feminist <strong>and</strong> Peace Perspectives on Women." In Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong><br />

Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong> Conflict. 3 vols. Edited by Lester Kurtz. San Diego, CA: Academic Press,<br />

1999, pp. 2:13-20. ISBN: 0122270118.<br />

Held, Virginia. "Gender as an Influence on Cultural Norms Relating to <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Environment." In Cultural Norms, <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Environment. Edited by Arthur H. Westing. New<br />

York, NY: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1988, pp. 44-51. ISBN: 0198291256.<br />

Hunter, Anne E., ed. On Peace, <strong>War</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Gender: A Challenge to Genetic Explanations. New<br />

York, NY: The Feminist Press, 1991.<br />

Ruddick, Sara. Maternal Thinking: Toward a Politics <strong>of</strong> Peace. Boston, MA: Beacon Press,<br />

1995.<br />

Tessler, Mark, Jodi Nachtwey, <strong>and</strong> Audra Grant. "Further Tests <strong>of</strong> the Women <strong>and</strong> Peace<br />

Hypothesis: Evidence from Cross-National Survey Research in the Middle East." International<br />

Studied Quarterly 43, no. 3 (September 1999): 519-532.<br />

Turpin, Jennifer. "Women <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong>." In Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong> Conflict. 3 vols.<br />

Edited by Lester Kurtz. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1999, pp. 3:801-813. ISBN:<br />

0122270118.<br />

Zalewski, Marysia, <strong>and</strong> Jane Parpart, eds. The "Man" Question in International Relations.<br />

Boulder, CO: Westview, 1997.<br />

Militarism<br />

Berghahn, Volker R. Militarism: The History <strong>of</strong> an International Debate, 1861-1979. New York,<br />

NY: St. Martins, 1982.<br />

Brodie, Bernard. <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> Politics. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1973, pp. 479-496.<br />

Bucholz, Arden. "Militarism." In Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong> Conflict. 3 vols. Edited<br />

by Lester Kurtz. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1999, pp. 2:423-433. ISBN: 0122270118.<br />

Burk, James. "Military Culture." In Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong> Conflict. 3 vols.<br />

Edited by Lester Kurtz. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1999, pp. 2:447-462. ISBN:<br />

0122270118.<br />

Cobden, Richard, ed. "The Three Panics." In Political Writings <strong>of</strong> Richard Cobden. London, UK:<br />

1887.<br />

Heise, Juergen Arthur. Minimum Disclosure: How the Pentagon Manipulates the News. New<br />

York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1979.

McLauchlan, Gregory. "Military-Industrial Complex, Contemporary Significance." In<br />

Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong> Conflict. 3 vols. Edited by Lester Kurtz. San Diego, CA:<br />

Academic Press, 1999, pp. 2:475-486. ISBN: 0122270126.<br />

Rourke, Francis E. Bureaucracy <strong>and</strong> Foreign Policy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University<br />

Press, 1972, pp. 18-40. ISBN: 0801813999.<br />

Shearer, Derek. "The Pentagon Propag<strong>and</strong>a Machine." In The Pentagon Watchers. Edited by<br />

Leonard Rodberg <strong>and</strong> Derek Shearer. New York, NY: Anchor, 1970, pp. 99-142.<br />

Vagts, Alfred. Defense <strong>and</strong> Diplomacy: The Soldier <strong>and</strong> the Conduct <strong>of</strong> Foreign Relations. New<br />

York, NY: Kings Crown, 1956, pp. 263-377 <strong>and</strong> 477-490.<br />

See also representative writings on war <strong>and</strong> international affairs by military <strong>of</strong>ficers, e.g.,<br />

Friedrich von Bernhardi, Ferdin<strong>and</strong> Foch, Giulio Douhet, Nathan Twining, Thomas Powers, <strong>and</strong><br />

Curtis LeMay.<br />

Nationalism - General Works<br />

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin <strong>and</strong> Spread <strong>of</strong><br />

Nationalism. Revised ed. London, UK: Verso, 1991.<br />

Van Evera, Stephen. "Hypotheses on Nationalism <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong>." International Security 18, no. 4<br />

(Spring 1994): 5-39.<br />

Gellner, Ernest. Nations <strong>and</strong> Nationalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983.<br />

Greenfeld, Liah. Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University<br />

Press, 1992.<br />

Hobsbawm, E. J. Nations <strong>and</strong> Nationalism Since 1780. New York, NY: Cambridge University<br />

Press, 1990.<br />

Posen, Barry R. "Nationalism, the Mass Army, <strong>and</strong> Military Power." International Security 18,<br />

no. 2 (Fall 1993): 80-124.<br />

Smith, Anthony D. The Ethnic Origins <strong>of</strong> Nations. Ox<strong>for</strong>d, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1986.<br />

———. Theories <strong>of</strong> Nationalism. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1983.<br />

Snyder, Louis L. Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Nationalism. New York, NY: Paragon House, 1990.<br />

Ingroup-Outgroup Dynamics<br />

Sherif, Muzafer, <strong>and</strong> Carolyn W. Sherif. Groups in Harmony <strong>and</strong> Tension: An Integration <strong>of</strong><br />

Studies on Intergroup Relations. New York, NY: Octagon Books, 1966.

Coser, Lewis A. The Functions <strong>of</strong> Social Conflict. New York, NY: Free Press, 1966.<br />

Nationalist Mythmaking<br />

Dance, E. H. History the Betrayer: A Study in Bias. London, UK: Hutchinson, 1960.<br />

Fitzgerald, Frances. America Revised: History Schoolbooks in the Twentieth Century. Boston,<br />

MA: Little, Brown, 1979.<br />

Hayes, Carlton J. H. "The Propagation <strong>of</strong> Nationalism." In Essays on Nationalism. New York,<br />

NY: Macmillan, 1926, pp. 61-92.<br />

Kennedy, Paul M. "The Decline <strong>of</strong> Nationalistic History in the West, 1900-1970." Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Contemporary History 8, no. 1 (January 1973): 77-100.<br />

Lewis, Bernard. History: Remembered, Recovered, Invented. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University<br />

Press, 1975.<br />

Shafer, Boyd C. Faces <strong>of</strong> Nationalism. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.<br />

Zinn, Howard. The Politics <strong>of</strong> History. Boston, MA: Beacon, 1970, pp. 5-34 <strong>and</strong> 288-319. ISBN:<br />

080705450X.<br />

Democratic Peace Theory, Dictatorial Peace Theory<br />

Andreski, Stanislav. "On the Peaceful Disposition <strong>of</strong> Military Dictatorships." Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Strategic Studies 3, no. 3 (December 1980): 3-10.<br />

Brown, Michael E., Sean M. Lynn- Jones <strong>and</strong> Steven E. Miller, eds. Debating the Democratic<br />

Peace: An International Security Reader. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996. ISBN:<br />

0262522136.<br />

Gleditsch, Nils Petter. "Peace <strong>and</strong> Democracy." In Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong><br />

Conflict. 3 vols. Edited by Lester Kurtz. San Diego: Academic Press, 1999, pp. 2:643-652.<br />

ISBN: 0122270126.<br />

Maoz, Zeev, <strong>and</strong> Bruce Russett. "Normative <strong>and</strong> Structural <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>of</strong> Democratic Peace, 1946-<br />

1986." American Political Science Review 87, no. 3 (September 1993): 624-638.<br />

Russett, Bruce, William Anholis, Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember, <strong>and</strong> Zeev Maoz. Grasping the<br />

Democratic Peace: Principles <strong>for</strong> a Post-Cold <strong>War</strong> World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University<br />

Press, 1993.

Human Instinct Theories <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Brown, Seyom. <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Prevention</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>. 2nd ed. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1994,<br />

pp. 9-15.<br />

Dougherty, James E., <strong>and</strong> Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr. Contending Theories <strong>of</strong> International<br />

Relations. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1990, pp. 274-288. ISBN: 0060417064.<br />

Freud, Sigmund. "Why <strong>War</strong>?" In Leon Bramson <strong>and</strong> George W. Goethals, eds., <strong>War</strong>: Studies<br />

from Psychology, Sociology, Anthropology, rev. ed. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1968. pp. 71-<br />

80.<br />

James, William. "The Moral Equivalent <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>." In <strong>War</strong>: Studies from Psychology, Sociology,<br />

Anthropology. Revised ed. Edited by Leon Bramson <strong>and</strong> George W. Goethals. New York, NY:<br />

Basic Books, 1968, pp. 21-31.<br />

Kim, Samuel S. "The Lorenzian Theory <strong>of</strong> Aggression <strong>and</strong> Peace Research: A Critique." In The<br />

<strong>War</strong> System: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Edited by Richard A. Falk <strong>and</strong> Samuel S. Kim.<br />

Boulder, CO: Westview, 1980, pp. 82-115. ISBN: 0865310424.<br />

McDougall, William. "The Instinct <strong>of</strong> Pugnacity." In The <strong>War</strong> System: An Interdisciplinary<br />

Approach. Edited by Richard A. Falk <strong>and</strong> Samuel S. Kim. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1980, pp. 33-<br />

43. ISBN: 0865310424.<br />

Mead, Margaret. "<strong>War</strong>fare is Only an Invention, Not a Biological Necessity." In The <strong>War</strong><br />

System: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Edited by Richard A. Falk <strong>and</strong> Samuel S. Kim. Boulder,<br />

CO: Westview, 1980, pp. 269-274. ISBN: 0865310424.<br />

Somit, Albert. "Humans, Chimps, <strong>and</strong> Bonobos: The Biological Bases <strong>of</strong> Aggression, <strong>War</strong>, <strong>and</strong><br />

Peacemaking." Journal <strong>of</strong> Conflict Resolution 34, no. 3 (September 1990): 553-582.<br />

Waltz, Kenneth N. Man, the State, <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong>. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1954,<br />

pp. 16-79.<br />

Religion <strong>and</strong> <strong>War</strong><br />

Freedman, David Noel, <strong>and</strong> Michael J. McClymond. "Religious Traditions, Violence, <strong>and</strong><br />

Nonviolence." In Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong> Conflict. Vol. 3. Edited by Lester Kurtz.<br />

San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1999, pp. 229-239. ISBN: 0122270118.<br />

A survey <strong>of</strong> the problem <strong>of</strong> religion <strong>and</strong> war.<br />

Huntington, Samuel P. The Clash <strong>of</strong> Civilizations <strong>and</strong> the Remaking <strong>of</strong> World Order. New York,<br />

NY: Simon <strong>and</strong> Schuster, 1996. ISBN: 0684811642.

Spencer, Robert, <strong>and</strong> David Pryce-Jones. Islam Unveiled: Disturbing Questions about the<br />

World's Fastest-Growing Faith. San Francisco, CA: Encounter Books, 2002. ISBN:<br />

1893554589.<br />

Civil <strong>War</strong>, its Control<br />

Stedman, Stephen John, Donald Rothchild, <strong>and</strong> Elizabeth M Cousens, eds. Ending Civil <strong>War</strong>s:<br />

The Implementation <strong>of</strong> Peace Agreements. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2003. ISBN:<br />

1588260836.<br />

Henderson, Errol A. "Civil <strong>War</strong>s." In Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong> Conflict. 3 vols.<br />

Edited by Lester Kurtz. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1999, pp. 1:279-288. ISBN:<br />

0122270118.<br />

———. "Ethnic Conflict <strong>and</strong> Cooperation," In Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Violence, Peace, <strong>and</strong> Conflict. 3<br />

vols. Edited by Lester Kurtz. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1999, pp. 1:751-764. ISBN:<br />

0122270118.<br />

Kumar, Radha. "The Troubled History <strong>of</strong> Partition." Foreign Affairs 76, no. 1 (January/February<br />

1997): 22-34.<br />

Montville, Joseph V., ed. Conflict <strong>and</strong> Peacemaking in Multiethnic Societies. New York, NY:<br />

Lexington Books, 1991.<br />

Sisk, Timothy D. Power Sharing <strong>and</strong> International Mediation in Ethnic Conflicts. Washington,<br />

DC: United States <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>of</strong> Peace, 1996.<br />

Negotiation <strong>and</strong> Diplomacy<br />

Cohen, Raymond. "The Rules <strong>of</strong> the Game in International Politics." International Studies<br />

Quarterly 24, no. 1 (March 1980): 129-50.<br />

Fisher, Roger. International Conflict <strong>for</strong> Beginners. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1969.<br />

Fisher, Roger, <strong>and</strong> William Ury. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In.<br />

Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.<br />

George, Alex<strong>and</strong>er L. Forceful Persuasion: Coercive Diplomacy as an Alternative to <strong>War</strong>.<br />

Washington, DC: United States <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>of</strong> Peace, 1991.<br />

Iklé, Fred Charles. How Nations Negotiate. Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint, 1982, first publication<br />

1964.<br />

Nicolson, Harold. Diplomacy. London, UK: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1964.

Mediation<br />

Bercovitch, Jacob, <strong>and</strong> David Wells. "Evaluating Mediation Strategies: A Theoretical <strong>and</strong><br />

Empirical Analysis." Peace <strong>and</strong> Change 18, no. 1 (January 1993): 3-25, <strong>and</strong> works cited therein.<br />

Princen, Thomas. Intermediaries in International Conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University<br />

Press, 1995.<br />

Limited <strong>War</strong><br />

Etzold, Thomas. "Clausewitzian Lessons <strong>for</strong> Modern Strategists." Air University Review<br />

(May/June 1980).<br />

Smoke, Richard. <strong>War</strong>: Controlling Escalation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977.<br />

For more references, see Smoke's bibliography.<br />

Arms Races<br />

Cashman, Greg. What <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>War</strong>? pp. 172-184.<br />

Huntington, Samuel P. "Arms Races: Prerequisites <strong>and</strong> Results." In The Use <strong>of</strong> Force. 3rd ed.<br />

Edited by Robert J. Art <strong>and</strong> Kenneth N. Waltz. New York, NY: University Press <strong>of</strong> America,<br />

1988, pp. 637-670. ISBN: 0819170038.<br />

Sample, Susan G. "Arms Races <strong>and</strong> Dispute Escalation: Resolving the Debate?" Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Peace Research 34, no. 1 (February 1997): 7-22.<br />

Historical Sources<br />

General surveys <strong>of</strong> global international history include:<br />

Gay, Peter, <strong>and</strong> R. K. Webb. Modern Europe. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1973.<br />

Palmer, Robert R., <strong>and</strong> Joel Colton. A History <strong>of</strong> the Modern World. 7th ed. New York, NY:<br />

Knopf, 1991.<br />

Ropp, Theodore. <strong>War</strong> in the Modern World. New York, NY: Collier, 1962.<br />

For more sources see the bibliography in Palmer <strong>and</strong> Colton. Another excellent bibliographic<br />

source is <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> Society Newsletter: A Bibliographical Survey. Edited by Jürgen Förster, David<br />

French, David Stevenson <strong>and</strong> Russel Van Wyk. Munich: Militärgeschlichtliches Forschungsamt,<br />

annual since 1973; it lists articles <strong>and</strong> book chapters relevant to international relations <strong>and</strong> war.<br />

General surveys <strong>of</strong> European international history:

Albrecht-Carrie, Rene. A Diplomatic History <strong>of</strong> Europe Since the Congress <strong>of</strong> Vienna. Revised<br />

ed. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1973.<br />

Hayes, Carlton J. H. Contemporary Europe Since 1870. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1962.<br />

Joll, James. Europe Since 1870: An International History. 4th ed. London, UK: Penguin, 1990.<br />

Taylor, A. J. P. Struggle <strong>for</strong> Mastery in Europe, 1848-1914. London, UK: Ox<strong>for</strong>d, 1971.<br />

Also pertinent are the relevant books in four series <strong>of</strong> general histories:<br />

The "Langer" series, published by Harper Torchbooks, 15-odd volumes covering western history<br />

since 1200, under the general editorship <strong>of</strong> William Langer (e.g. Sontag, Raymond. A Broken<br />

World, 1919-1939.)<br />

The Longman's "General History <strong>of</strong> Europe" series, covering western history since Roman times,<br />

published by Longman, under the general editorship <strong>of</strong> Denys Hays (e.g. Roberts, J. M. Europe<br />

1880-1945.)<br />

The Fontana "History <strong>of</strong> Europe" series, published by Fontana/Collins, covering history since the<br />

middle ages, under the general editorship <strong>of</strong> J.H. Plumb (e.g. Grenville, J. A. S. Europe<br />

Reshaped, 1848-78.)<br />

The "New Cambridge Modern History" <strong>and</strong> "Cambridge Ancient History" series, covering<br />

western history from the beginning.<br />

The Seven Years <strong>War</strong><br />

An overview:<br />

Anderson, Fred. Crucible <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong>: The Seven Years' <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Fate <strong>of</strong> Empire in British North<br />

America. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.<br />

On the Franco-British conflict in the Seven Years <strong>War</strong>:<br />

Black, Jeremy. The Origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> in Early Modern Europe. Edinburgh: J. Donald, 1987.<br />

Higonnet, Patrice. "The Origins <strong>of</strong> the Seven Years <strong>War</strong>." Journal <strong>of</strong> Modern History 40 (1968):<br />

57-90.<br />

On the Prussian-Austrian-Russian-French war <strong>of</strong> 1756:<br />

Gaxotte, Pierre. Frederick the Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1942, pp. 175-229<br />

<strong>and</strong> 303-342.<br />

Reiners, Ludwig. Frederick the Great. New York, NY: Putnam, 1960, pp. 89-121 <strong>and</strong> 147-164.

Ritter, Gerhard. Frederick the Great. Berkeley, CA: University <strong>of</strong> Cali<strong>for</strong>nia Press, 1974, pp. 73-<br />

148. ISBN: 0520027752.<br />

The Crimean <strong>War</strong><br />

Goldfrank, David M. The Origins <strong>of</strong> the Crimean <strong>War</strong>. New York, NY: Longman, 1994.<br />

Palmer, Alan. The Banner <strong>of</strong> Battle: The Story <strong>of</strong> the Crimean <strong>War</strong>. New York, NY: St. Martin's,<br />

1987.<br />

Rich, Norman. Why the Crimean <strong>War</strong>? A Cautionary Tale. Hanover, NH: University Press <strong>of</strong><br />

New Engl<strong>and</strong>, 1985.<br />

Smoke, Richard. "The Crimean <strong>War</strong>." In <strong>War</strong>: Controlling Escalation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard<br />

University Press, 1977, pp. 147-194. ISBN: 0674945956.<br />

The Italian <strong>War</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Independence<br />

Coppa, Frank J. The Origins <strong>of</strong> the Italian <strong>War</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Independence. New York, NY: Longman,<br />

1992.<br />

The <strong>War</strong>s <strong>of</strong> German Unification<br />

Carr, William. The Origins <strong>of</strong> the <strong>War</strong>s <strong>of</strong> German Reunification. White Plains, NY: Longman,<br />

1991.<br />

Craig, Gordon. The Politics <strong>of</strong> the Prussian Army, 1640-1945. New York, NY: Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

University Press, 1964, pp. 180-216. ISBN: 0195002571.<br />

Smoke, Richard. <strong>War</strong>: Controlling Escalation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977,<br />

pp. 80-146. ISBN: 0674945956.<br />

World <strong>War</strong> I<br />

Basic histories include:<br />

Berghahn, V. R. Germany <strong>and</strong> the Approach <strong>of</strong> <strong>War</strong> in 1914. London, UK: Macmillan, 1973.<br />

Geiss, Imanuel. German Foreign Policy 1871-1914. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul,<br />

1976.<br />

Joll, James. The Origins <strong>of</strong> the First World <strong>War</strong>. New York, NY: Longman, 1984.<br />

Lieven, D. C. B. Russia <strong>and</strong> the Origins <strong>of</strong> the First World <strong>War</strong>. New York, NY: St. Martin's,<br />

1983.

Tuchman, Barbara. The Guns <strong>of</strong> August. New York, NY: Dell, 1962.<br />

Turner, L. C. F. Origins <strong>of</strong> the First World <strong>War</strong>. London, UK: Arnold, 1970.<br />

Suveys <strong>of</strong> debates about the war's origins are:<br />

Ferguson, Niall. "Germany <strong>and</strong> the Origins <strong>of</strong> the First World <strong>War</strong>: New Perspectives."<br />

Historical Journal 35 (September 1992): 725-52.<br />

Langdon, John W. July 1914: The Long Debate, 1918-1990. New York, NY: St. Martin's, 1991.<br />

Moses, John A. The Politics <strong>of</strong> Illusion: The Fischer Controversy In German Historiography.<br />

London, UK: George Prior, 1975.<br />

Other sources on the origins <strong>of</strong> the war include:<br />

Albertini, Luigi. The Origins <strong>of</strong> the <strong>War</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1914. 3 vols. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980.<br />

Reprint <strong>of</strong> 1952-1957 edition. Albertini is chaotic, but essential reading <strong>for</strong> those researching<br />

World <strong>War</strong> I.<br />

Fischer, Fritz. <strong>War</strong> <strong>of</strong> Illusions. New York, NY: Norton, 1975.<br />

Geiss, Imanuel, ed. July 1914: The Outbreak <strong>of</strong> the First World <strong>War</strong>: Selected Documents. New<br />

York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1967.<br />

Herwig, Holger H., ed. The Outbreak <strong>of</strong> World <strong>War</strong> I: <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>and</strong> Responsibilities. 5th ed.<br />

Revised. Lexington, MA: DC Heath, 1991.<br />

Jarausch, Konrad H. The Enigmatic Chancellor: Bethmann Hollweg <strong>and</strong> the Hubris <strong>of</strong> Imperial<br />

Germany. New Haven, CT: Yale, 1973.<br />

Röhl, John C. G. The Kaiser <strong>and</strong> his Court: Wilhelm II <strong>and</strong> the Government <strong>of</strong> Germany.<br />

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 162-190. ISBN: 0521402239.<br />

(on the German "war council" <strong>of</strong> December 8, 1912 <strong>and</strong> related matters.)<br />

Schmitt, Bernadotte E. The Coming <strong>of</strong> the <strong>War</strong>: 1914. 2 vols. Chicago, IL: University <strong>of</strong> Chicago<br />

Press, 1930.<br />

Contemporary descriptions <strong>of</strong> the political climate in Germany are:<br />

Hull, Isabel. The Military Entourage <strong>of</strong> Kaiser Wilhelm II 1888-1918. Cambridge, MA:<br />

Cambridge University Press, 1982.<br />

Archer, William., ed. 501 Gems <strong>of</strong> German Thought. London, UK: T. Fisher Unwin, 1916.

Bang, J. P. Hurrah <strong>and</strong> Hallelujah: The Teaching <strong>of</strong> Germany's Prophets, Pr<strong>of</strong>essors <strong>and</strong><br />

Preachers. New York, NY: Doran, 1917.<br />

Notestein, Wallace. Conquest <strong>and</strong> Kultur: Aims <strong>of</strong> Germans in Their Own Words. Washington,<br />

DC: Committee on Public In<strong>for</strong>mation, 1917.<br />

Thayer, William Roscoe, ed. Out Of Their Own Mouths. New York, NY: Appleton, 1917.<br />

Other works on themes pertinent to this course include:<br />

Brodie, Bernard. <strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> Politics. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1973, pp. 1-28.<br />

Clarke, I. F. Voices Prophesying <strong>War</strong>. London, UK: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1966.<br />

Coetzee, Marilyn Shevin. The German Army League: Popular Nationalism in Wilhelmine<br />

Germany. New York, NY: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1990.<br />

Craig, Gordon. The Politics <strong>of</strong> the Prussian Army, 1640-1945. New York, NY: Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

University Press, 1964, pp. 217-341.<br />

Ritter, Gerhard. The Sword <strong>and</strong> the Scepter: The Problem <strong>of</strong> Militarism in Germany. 4 vols.<br />

Coral Gables, FL: University <strong>of</strong> Miami Press, 1969-73.<br />

———. The Schlieffen Plan: Critique <strong>of</strong> a Myth. London, UK: Wolff, 1958.<br />

Guill<strong>and</strong>, Antoine. Germany <strong>and</strong> Her Historians. New York, NY: McBride, Nast, 1915.<br />

Hayes, Carleton J. H. France: A Nation <strong>of</strong> Patriots. New York, NY: Octagon, 1974.<br />

Hull, Isabel. The Military Entourage <strong>of</strong> Kaiser Wilhelm II, 1888-1918. Cambridge, UK:<br />

Cambridge University Press, 1982.<br />

Kitchen, Martin. "The Army <strong>and</strong> the Civilians." Chapter 6 in The German Officer Corps, 1890-<br />

1914. Ox<strong>for</strong>d, UK: Clarendon, 1968, pp. 115-142. ISBN: 0198214677.<br />

Kohn, Hans. The Mind <strong>of</strong> Germany. New York, NY: Scribner's, 1960, pp. 251-305.<br />

Knightley, Phillip. The First Casualty: From the Crimea to Vietnam. New York, NY:<br />

Quadrangle, 1975, pp. 80-112. ISBN: 0156311305.<br />

(on wartime press coverage.)<br />

Luvaas, Jay. The Military Legacy <strong>of</strong> the Civil <strong>War</strong>: The European Inheritance. Chicago. IL:<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 1959.<br />

McClell<strong>and</strong>, Charles. The German Historians <strong>and</strong> Engl<strong>and</strong>. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge<br />

University Press, 1971, pp. 168-235. ISBN: 0521080630.

Moses, John A. "Pan-Germanism <strong>and</strong> the German Pr<strong>of</strong>essors 1914-1918." Australian Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Politics & History 15, no. 3 (December 1969): 45-60.<br />

Sagan, Scott. "1914 Revisited: Allies, Offense, <strong>and</strong> Instability." International Security 11, no. 2<br />

(Fall 1986): 151-176.<br />

Snyder, Louis L. From Bismarck to Hitler. Williamsport, PA: Bayard, 1935.<br />

———. "Historiography" <strong>and</strong> "Militarism." Chapter 6 <strong>and</strong> Chapter 10 in German Nationalism:<br />

Tragedy <strong>of</strong> a People. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat, 1969. ISBN: 0804604339.<br />

Snyder, Jack. The Ideology <strong>of</strong> the Offensive: Military Decision Making <strong>and</strong> the Disasters <strong>of</strong><br />

1914. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984.<br />

Taylor, A. J. P. <strong>War</strong> By Time-Table. London, UK: 1969.<br />

Trachtenberg, Marc. "The Meaning <strong>of</strong> Mobilization in 1914." International Security 15, no. 3<br />

(Winter 1990/91): 120-150.<br />

Travers, Tim. The Killing Ground: The British Army, The Western Front <strong>and</strong> the Emergence <strong>of</strong><br />

Modern <strong>War</strong>fare, 1900-1918. Boston, MA: Allen & Unwin, 1987.<br />

Travers, T. H. E. "Technology, Tactics <strong>and</strong> Morale: Jean de Bloch, the Boer <strong>War</strong>, <strong>and</strong> British<br />

Military Theory, 1900-1914." Journal <strong>of</strong> Modern History 51, no. 2 (June 1979): 264-286.<br />

Willems, Emilio. A Way <strong>of</strong> Life <strong>and</strong> Death: Three Centuries <strong>of</strong> Prussian-German Militarism: An<br />

Anthropological Approach. Nashville, TN: V<strong>and</strong>erbilt University Press, 1986.<br />

Readable accounts <strong>of</strong> the war itself include:<br />

Gilbert, Martin. The First World <strong>War</strong>. New York, NY: Henry Holt, 1994.<br />

Taylor, A. J. P. The First World <strong>War</strong>. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1966.<br />

On Versailles an introduction is:<br />

Sharp, Alan. The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking in Paris, 1919. New York, NY: St.<br />

Martin's, 1991.<br />

Wold <strong>War</strong> II in Europe<br />

Baldwin, Peter, ed. "The Historikerstreit in Context." In Reworking the Past: Hitler, the<br />

Holocaust <strong>and</strong> the Historian's Debate. Boston, MA: Beacon, 1990, pp. 3-37. ISBN:<br />

0807043028.

Bartov, Omer. Hitler's Army: Soldiers, Nazis, <strong>and</strong> the <strong>War</strong> in the Third Reich. New York, NY:<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1991.<br />